September 17th, 2012—Monday morning. Oxford, England.

Having finished my mad dash up to the Cupola of the Sheldonian Theatre, I returned to the Old Bank Hotel, organized my suitcase in 10 minutes (remember…packing only what you absolutely need is the most luxurious thing you can do for your traveling-self), and was ready for my 11AM reunion with Anne and David Guy, who were driving down from their home in the Midlands. For many months previous, Anne had emailed suggestions about how best to spend this week we’d be together, and she’d worked up an itinerary which would satisfy any curious and energetic traveler. The question was–given that I was still ailing, and thus not energetic–would I survive the fun? I’d fortified myself with too much coffee at breakfast, and so caffeine, along with adrenaline from the joy of once again seeing my dear friends, would have to carry me.

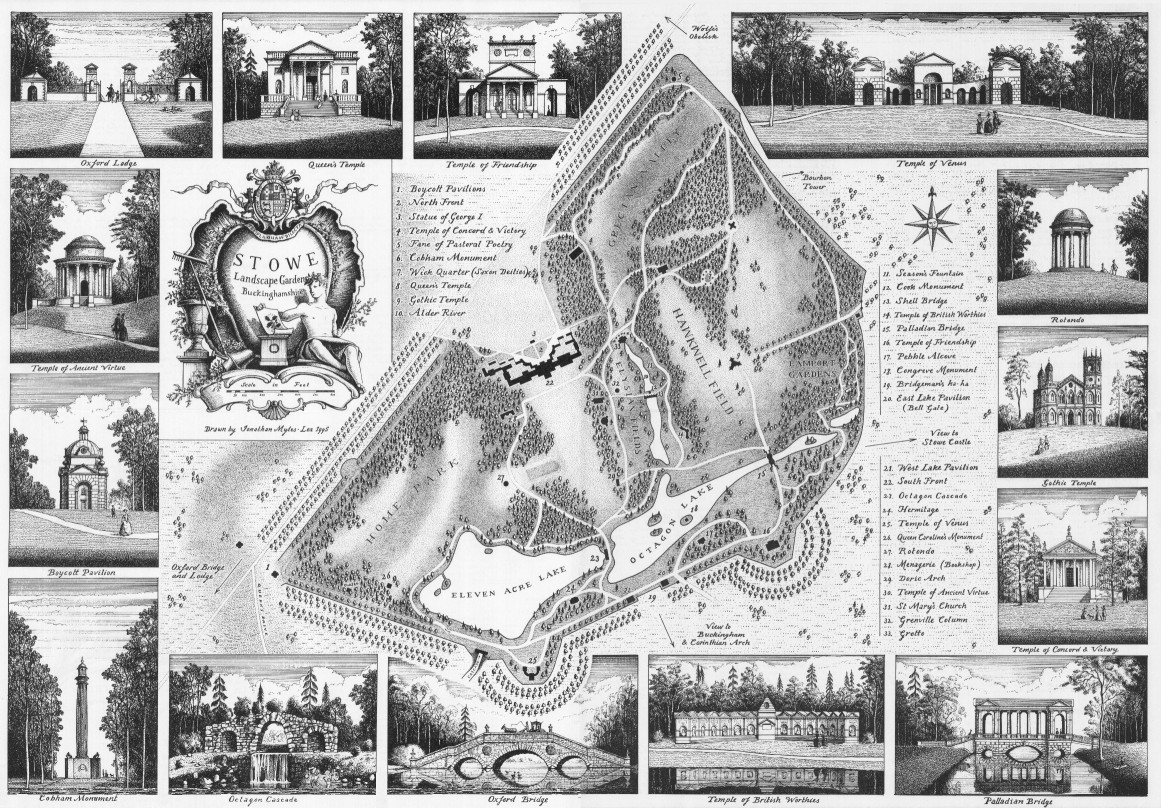

Our first destination on that chilly day was Stowe Landscape Gardens, 30 miles northeast of Oxford, in Buckinghamshire. Neither Anne nor David had been to Stowe, and so, unlike many of the other places they’d scheduled for the coming week, we could all experience Stowe with fresh eyes.

[A note about those eyes: Anne and I both meticulously record our travels with photos, and so in this Chapter, Anne’s photos which she kindly allows me to include will be identified “AG.”]

The first hint that serious grandeur’s afoot amid Stowe’s rolling pastures is the Corinthian Arch, which guards the long approach from town.

We parked the car, quickly scarfed down some tea-and-scones ( I call English Tea “Grease Tea,” because of all that delicious clotted cream and butter), bundled up, and began our hike toward the Gardens. We were gobsmacked at the scale—and ambition—of the place.

Stowe: Main House, with Octagon Lake. Note: This large lake was originally octagonal, but over the years its borders were softened & naturalized.

Not until we’d wandered for several hours did we fully appreciate how large Stowe is (I later learned it covers 205 acres).

Sir Richard Temple, the future Viscount Cobham, began to create these gardens in 1733, on the land where his family had grazed their sheep since 1589.

Having earlier in September been in Florence, where I toured the heavily-symbolic garden of Cosimo de Medici at Castello, I was interested to see, here on English soil, how Sir Richard Temple and his heirs—18th century aristocrats who claimed to be descended from Leofric and Lady Godiva, but who actually began as yeoman sheep farmers—carried on the Italian Renaissance tradition of building gardens that embodied poetry and politics; where every garden folly and every statue was pregnant with meanings that only the most cultured and politically acute visitors could appreciate….which is not to suggest, however, that I had a clue about what those pregnancies were.

After our visit, I bought the National Trust’s book, STOWE: THE PEOPLE & THE PLACE, which summarizes the significance of the landscape’s major features, and also provides this overview:

“One of the most remarkable legacies of Georgian England, Stowe came to reflect a coherent programme of ideas based on Cobham’s hugely influential network of political affiliations, and it was realized by that 18th century master of garden design, William Kent.“ With the help of Lancelot ‘Capability’ Brown—then at the beginning of his career, “Cobham’s immediate successors enhanced and extended the garden, naturalizing its more formal aspects and opening up fresh vistas. Political influence had given the Temple family fast wealth and power. But it also gave them huge ambition.” The Temples maneuvered their way up the aristocratic food-chain by buying titles for themselves, but, inevitably, over the years, the family purse was depleted and “retrenchments followed, ending with the sale of the house and garden in 1922. The National Trust first became involved in 1967 and took over formal ownership in 1990, initiating major restoration.”

Gothic Temple. AG. Note: this building can be rented for holiday stays, by the week, through the Landmark Trust.

Referring again to the National Trust’s guidebook: “Stowe’s greatest admirer was the Empress Catherine the Great of Russia, who was fascinated…and sent her gardener Vasily Neelov to England in 1770-71 to ‘visit all the notable gardens and, having seen them, lay out similar ones here.’ Neelov spent the rest of his life recasting Catherine’s pleasure grounds at Tsarkoe Selo and Peterhof in the English style. The former contains a Palladian Bridge, rostral column, Corinthian Arch and Pyramid: all directly derived from Stowe. Unable to visit Stowe herself, the Empress was constantly reminded of the gardens and their significance: the celebrated Frog dinner service, commissioned by her from Wedgwood in 1773, has more views of Stowe than of any other garden.”

Parsing the deepest meanings of Stowe’s temples and sculptures is something best left to garden historians. But mere day-trippers can gain much pleasure from Stowe’s long avenues and surprising vistas; from the swans and ducks who paddle about on its 8 lakes; from the numerous temples and follies; and from the expanses of neatly-nibbled fields (thanks to the picturesque flocks of sheep…but watch your step: the grass is well-fertilized).

View from the Temple of Ancient Virtue down across lake toward Temple of British Worthies, which celebrates the smartest in the Land. Note: NO amount of human ingenuity can outwit the moles who tunnel under the lawns.

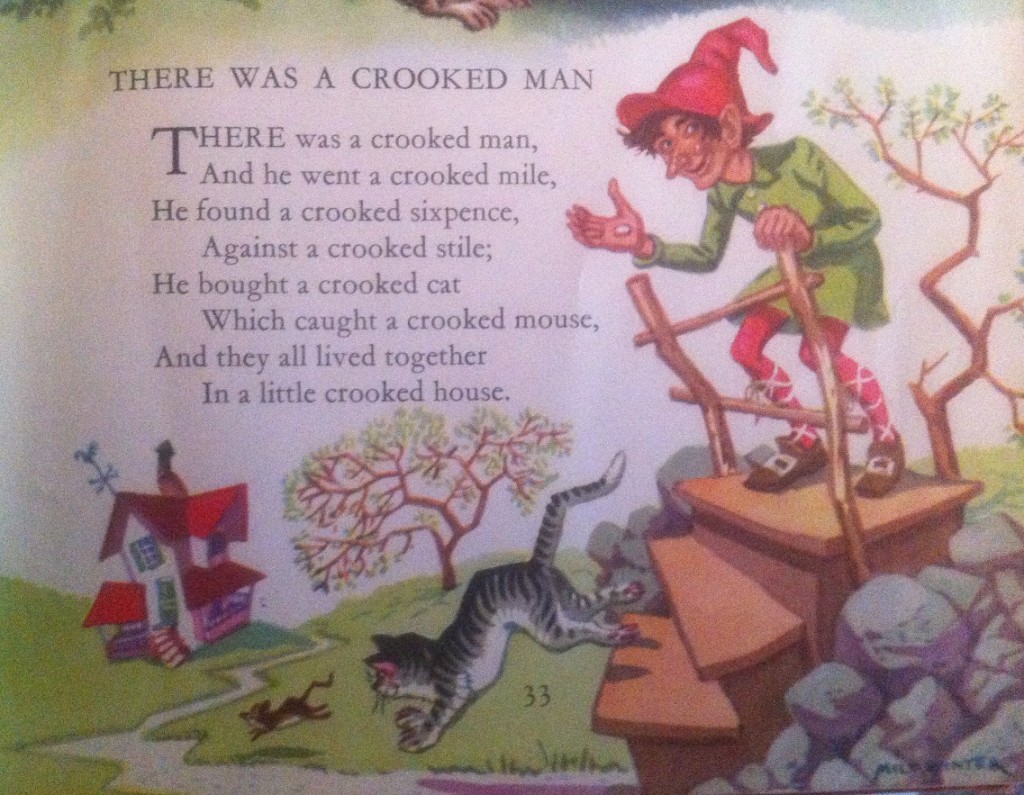

I loved rambling across Stowe’s grounds. But, probably, because I’m a simple soul, the happiest moment on that Monday was when I climbed a stile. Until that day, to me, stiles had only been words from nursery rhymes. David, who spent the afternoon at Stowe filming our adventures, swears he has a tape of me chortling as I prance up and over a stile, but hopefully he’ll keep that under lock and key.

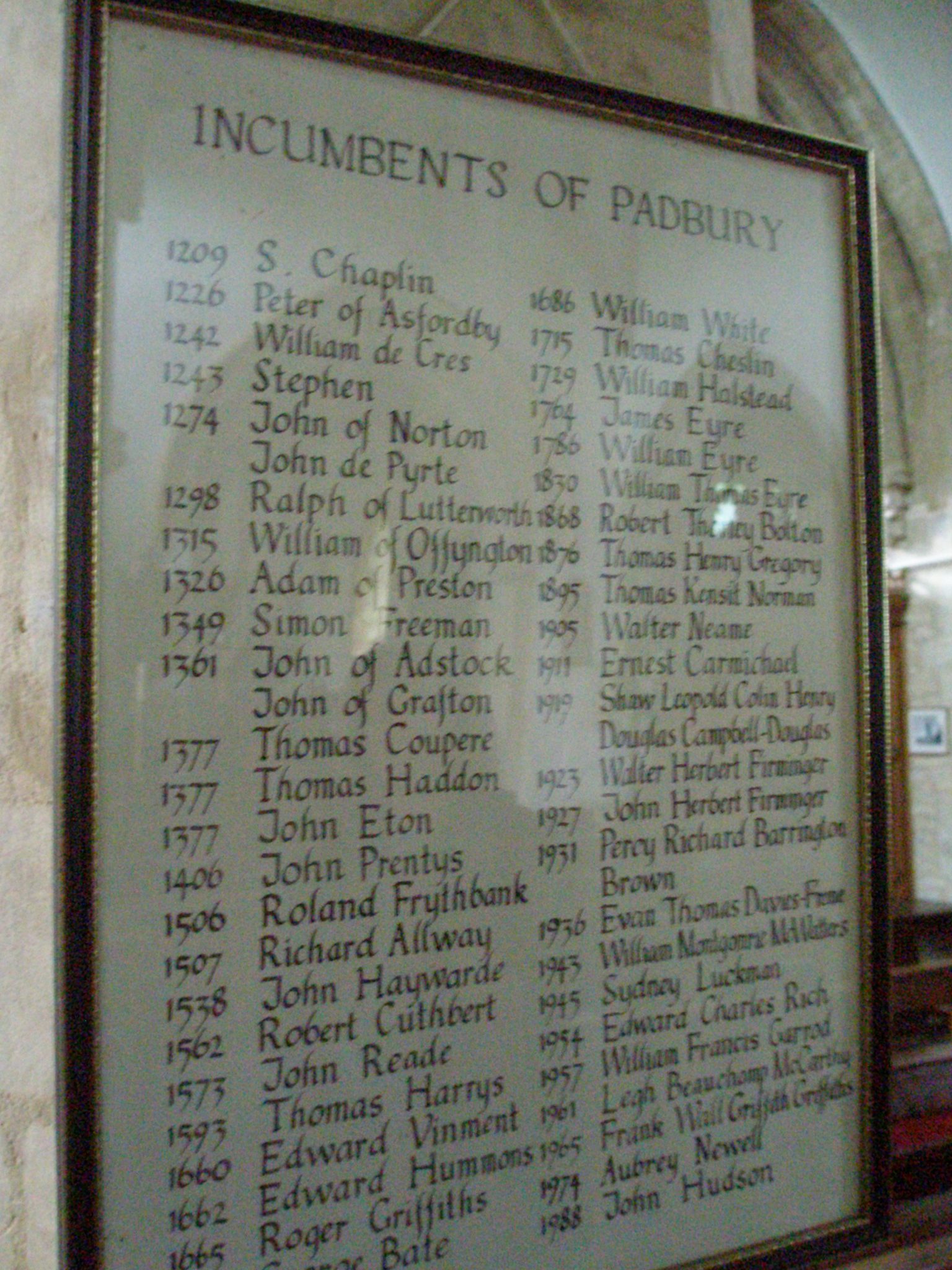

Our second destination that afternoon was the nearby village of Padbury, a Buckinghamshire hamlet that’s been around for quite a while: it appears in the Domesday Book of 1086, and was at that time one of the few villages in the country still owned by an Old English, rather than a Norman family. My reason for this little detour was personal. All of us in America are descendants of the restless, or the malcontented; the religiously-persecuted, the poor, or the enslaved. However varied the events may have been which propelled our antecedents away from their homelands and out across the oceans, once each of those travelers set foot upon American soil, their lives had to be started over, for better or worse.

In 1635, for reasons unknown, my ancestor William Buck and his 18-year-old son Roger left Padbury, and sailed on the ship Increase to Boston, where they established themselves as plough-wrights (plow-sharpeners) and farmers, on a 20 acre lot in Cambridge, Massachusetts, just north of where Radcliffe College today stands. For a time, Roger supplemented his income by serving as Public Executioner in Cambridge, which required him to do some culprit-lashing. How NICE to know that I have such illustrious forebears! In any case, since Padbury is near to Stowe, Anne suggested we visit the town’s ancient Church of St. Mary the Virgin, which was established in 1210; a place where William Buck would have worshipped, and married. As the skies darkened and threatened rain, we arrived at the Church.

Thinking old gravestones might tell me stories, I poked around but immediately discovered that the oldest stones dated only to the early 1800’s; I’m sure layers and layers of the previously-deceased still lie peacefully, deeper down…where else could they go?

The Church was unlocked and unpeopled. Happily, helpful Church history sheets were posted, so we were able to learn that St.Mary’s was rebuilt and extended in 1250, and then again in 1330, by which time it had attained its current size and shape. I’m not a genealogist (I prefer to live in the present),

but being inside the chilly, dim space—with its dry, ancient smells; where ancient frescoes and crude carvings coexist with Xeroxed notices and a children’s toy-filled Sunday school nook (…and in Padbury, Sunday School is held on Wednesdays!)— was sobering and inspiring. This building is where Padbury residents have congregated for 800 years, and was where William Buck might well have pondered his momentous decision to leave all he’d known, for the New World. It’s good to remember that we Americans come from such

intrepid stock.

September 18th, Tuesday. Worcestershire.

As on my previous visit with Anne and David, Anne’s superb mum,Janet Hardwick, opened her elegant home to me. On Monday night, after

Anne and David dropped me off, Janet had hustled me into to her guest room, where a furry hot water bottle warmed the bedsheets. And at breakfast time,Janet and her cat Tink fed me in their beautiful sun room. Thanks to Janet’s tender care, my ailments began to feel less severe.

Janet’s back garden, as seen from her Sun Room. Of course, this lovely little spot was designed by Anne Guy, & installed by Anne and David Guy.

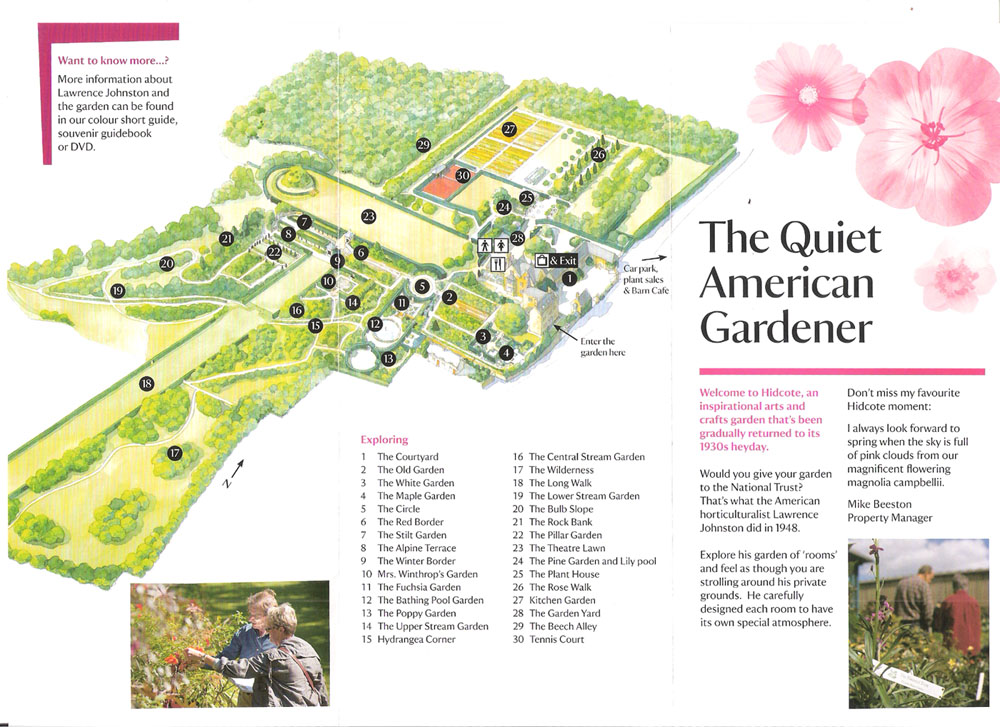

Our Tuesday Plan was a visit to Hidcote Manor Garden, one of the most famous gardens in England. The 17th century Manor house, and grounds, are located in the northern Cotswolds, 10 miles south of Stratford-upon-Avon, on the Gloucester-Warwickshire border. In my month of garden-visiting, in Italy and in England, only at Hidcote did I encounter tour buses; the entire garden-loving-World seemed to have descended. Amazingly, Hidcote’s series of outdoor “rooms” managed to absorb the crowds, and Janet and Anne and David and I often had entire areas to ourselves.

In 1907, Lawrence Johnson and his rather crotchety mother Gertrude Winthrop–wealthy American expatriates–made an offer on the Manor house and its 287 acres of farmland. Putting down a deposit of 10 Pounds, Johnson contracted to buy the Estate for 7200 Pounds.

Johnson busied himself with house renovations and began to amass books on horticulture, which helped him to thereafter gather his huge collection of rare plants, for which he soon began planning the enormous series of terraces and walls and gazebos and bridges and paths and lawns and topiaries and hedges and ponds and flower gardens that we see today (Gasp!); just listing all these garden features is exhausting. Hidcote’s plan is almost maze-like; from no vantage point can the entirety of the landscape be seen. Each space seems a place unto itself, and walking from one area into another is sometimes disorienting, due to the lack of a unifying theme. But that constant element of surprise ultimately makes for a garden that’s FUN to explore, and, for a blossom-lover, the lushly-planted flower beds are virtual master-classes in color theory.

By 1930, when COUNTRY LIFE magazine published the first account of Johnson’s garden, his creation had 20 years of growth under its belt. The gardens that today’s visitors encounter have reached full maturity, and are in splendid condition, because the National Trust (also the keepers of the Stowe Landscape Gardens), which operates the property, performs the miracle of maintaining the gardens to Johnson’s exacting standards.

Throughout the gardens, lush plantings, rich textures, and saturated colors abound. My camera battery had finally died from exhaustion (and the camera’s operator was feeling similarly), but fortunately, Anne took these ravishing close-ups:

Everything at Hidcote was ship-shape, even the Ladies’ Loo, which had been awarded a “2012 Loo of the Year Award” (I kid you not).

Everything at Hidcote was ship-shape, even the Ladies’ Loo, which had been awarded a “2012 Loo of the Year Award” (I kid you not).

September 19th, Wednesday.

After all the greenery of the past two days, Wednesday was a time instead for

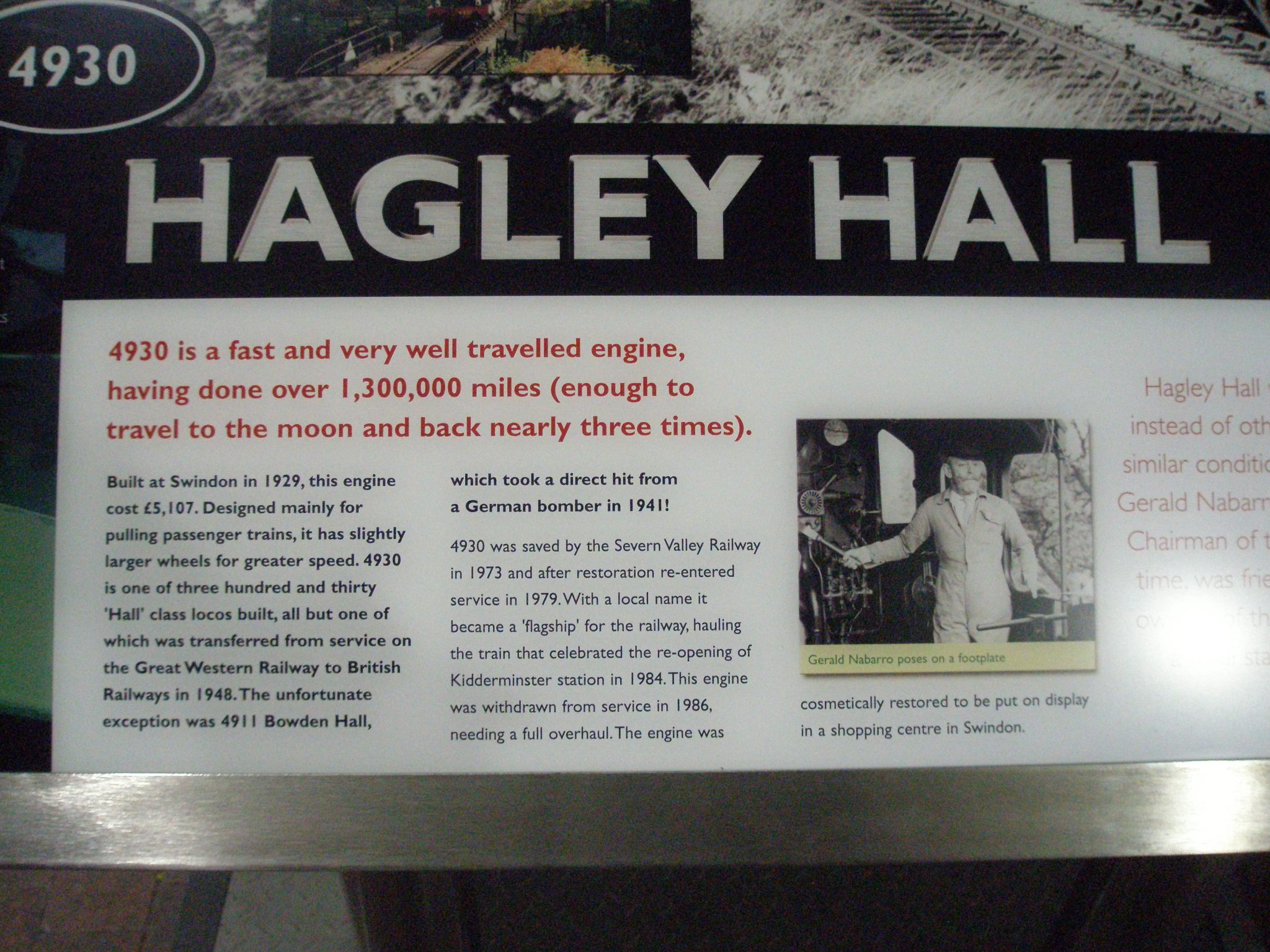

some cold, hard steel, and so the four of us set out to travel on the historic Severn Valley Railway, a network of steam-hauled, vintage passenger trains that run for about 16 miles, alongside the beautiful River Severn, between Kidderminster, Bewdley and Bridgnorth.

These coal-fired engines and period carriages, which have been restored in the Railway’s own workshops, are enjoyed mainly by Brits; I was the only American chugging along among the happy travelers that day.

The very same carriage that George Smiley took to Penzance, in John le Carre’s

book SMILEY’S PEOPLE, which I’d finished rereading, the night before.

At the Bewdley Station, the platform was teeming with schoolchildren, some in 1940s, period dress.

Costumed or not, all the kids clutched gas masks and each carried one little suitcase. Luggage labels were threaded though each child’s coat button hole, with name and address clearly marked. Anne told me that such school expeditions are common: teachers are keeping alive awareness of the trauma of the mass evacuations of British children–from bomb-targeted cities out into the countryside–that occurred During WWII. Janet nodded…yes, she knew all about these things: her older brother had also been one of those little travelers.

And so I learned something new that day, along with the 7-year-olds!

David filming me photographing him. Actually, it’s lots of fun to ride in a train while

hanging your head out of the window. The only drawback: steam trains yield soot, and my face looked like a chimney sweep’s by the end of the day.

Yesterday, a Loo of the Year Award at Hidcote. Today, a Station Flower Garden Award at Highley. The Brits DO love their awards.

In my next Chapter: Far-flung travels. Liverpool–Antony Gormley at the Irish Sea; Albert Dock; The Three Graces; Childhood homes of Lennon, & McCartney…

…followed by The Ruins at Great Witley,

and then by a visit to Jane Austen’s house at Chawton.

2012 Copyright Nan Quick–Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

5 Responses to Major Ramblings Across the English Countryside: Stowe Landscapes; Hidcote Garden; Severn Valley Railway.