Crosby Beach, Liverpool, England. Nan, striding toward the Irish Sea to inspect one of Antony Gormley’s “Another Place” iron men.AG

September 20th, 2012. Liverpool, England. I was still ailing in body but was otherwise feeling quite exuberant, due to my pleasure at being able to spend time with my British friends Anne and David Guy, and Janet Hardwick.

(Note: Once again, the photos that Anne took, and which she generously allows me to include here, will be marked “AG.”)

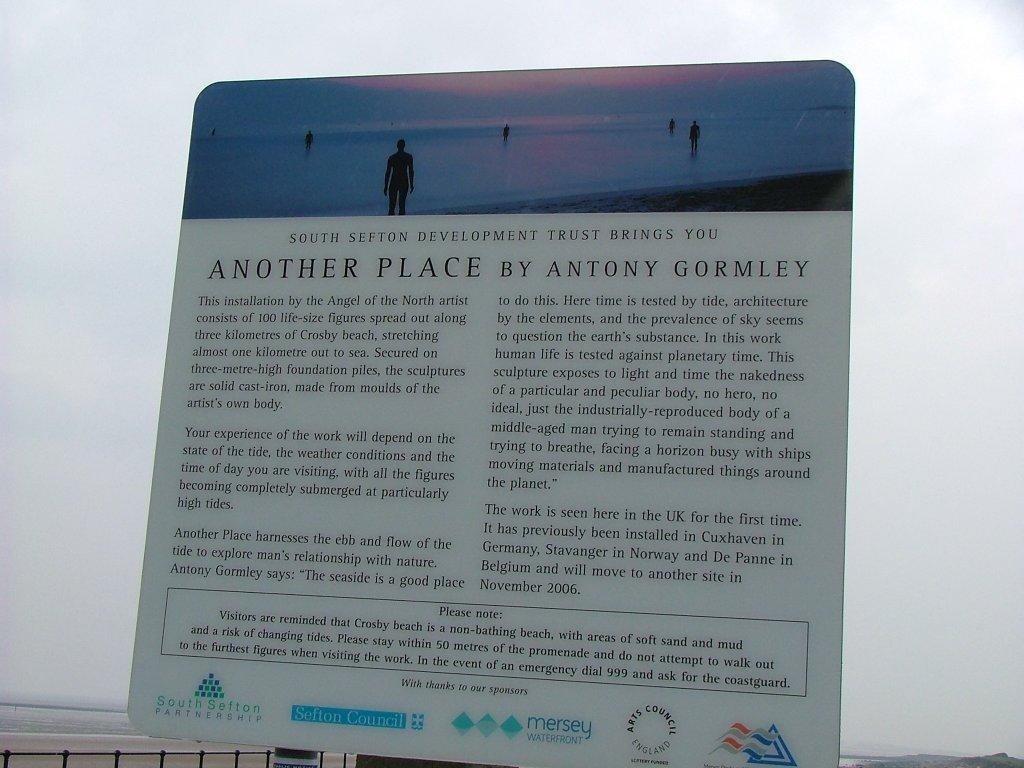

We’d arisen early that Thursday morning, and had made the 2+ hour-long drive north through rain and fog from The Midlands to Crosby Beach, just outside of Liverpool. Wet, gray skies were apparently the best the day’s weather-menu could offer, and, dressed in every scrap of warm clothing I’d packed, along with hat and gloves loaned by Janet, I tumbled out of the car and began my much-anticipated inspection of sculptor Antony Gormley’s “Another Place,” a 100-statue installation at the edge of the Irish Sea.

2 of the 100 cast iron statues by Antony Gormley that are mounted on Crosby Beach. Liverpool’s western-most suburbs which lie across the Mersey Estuary from the City Centre are in the background. AG

Everything about Liverpool suggests being at an EDGE; of a leaning away from the familiar toward something ELSE. This peculiar atmosphere isn’t simply due to the way the City clings to the eastern side of the Mersey Estuary, which leads to the turbulent Irish Sea. There’s a saltiness in the air that causes a restlessness and an urge for embarkation: unending streams of ships headed to Ireland and beyond make one long to turn one’s back to the land, and hop aboard one of those vessels. There’s a starkness in the northern light that lends a sand-blasted sheen to the heroically-scaled buildings on the waterfront. There’s that edge of irony in the Scouser locals’ humor that sneaks a smile into almost every conversation (…remember John Lennon’s famous introduction for the Beatles’ Royal Variety Performance of “Twist and Shout:” “Would the people in the cheaper seats clap your hands, and the rest of you… if you’ll just rattle your jewelry.”). There’s an APARTNESS in Liverpool, a sense that, while it belongs to England, the City’s essence comes from jumbled spices of distant cultures. This worldliness is the inevitable result of Liverpool’s having been a major port: by the early 19th century, 40% of the world’s trade passed through the City’s docks. The City has the oldest Chinese community in Europe, and the longest-established Black African neighborhood in England. During WWII, most American servicemen arrived in England via the Port of Liverpool, and with them came refreshing strains of culture and music that profoundly affected the City’s youngsters. Characterizing the spirit of Liverpool without resorting to cringe-making poetics is impossible, because any attempt to describe Liverpool in strictly prosaic terms tells only half of its truth.

It was into this evocative setting that, in 2005, British sculptor Antony Gormley stormed.

He’d used his own body as the basis for 100 cast iron figures, which he mounted over a two-mile stretch of Crosby Beach. Those figures, which have already become encrusted with lichen and marked by rust, all face toward the Irish Sea and are recognizably male. When they first appeared, the 100 simplified penises that also pointed (but gently…they’re not erect) toward the sea caused a ruckus, and community protests, and cries of “pornography!” Disgusted at the hubbub, Gormley decried Britain’s “risk-averse culture,“ and began to consider

moving the statues to the banks of the Hudson River, in New York State.

But, despite the controversy, after a couple of years the local council agreed that the installation, which had attracted international attention and had also become much-loved by beach-walkers (who at times gussie-up the statues in all manner of costumes), did in fact have artistic merit, and so Gormley’s massive work was granted permanent resident status. Gormley’s doppelgangers look out over the wind farms in the Irish Sea, and, depending upon the weather, the time of day, and the level and direction of the tides, as well as upon the number of his figures that one chooses to hold in one’s field of vision, his massive artwork elicits innumerable emotions and impressions. When the tides rush in (and they do RUSH, as I discovered when my boots suddenly filled with water…I should have known something was up when the old gentleman who was clamming in the shallows, grabbed his bucket, and slogged inland, just as I splashed in the opposite direction)…

…the Gormley men who resolutely march into the surf seem suicidal…or perhaps they’re only mermen, returning home. But, in the sunshine, or against a sunset, (I’ve consulted many photos of the site, taken in different conditions), his cast iron army can seem celebratory…or like an alien invasion. Marvelous stuff. Here are photos, taken on other days, by other visitors….

…and here’s what Anne and David and Janet and I saw on that chilly Thursday:

The rain, which had been only spitting, began to earnestly pour, and so we retreated from Crosby Beach, and drove to Liverpool’s city waterfront, which, in 2004, was granted World Heritage Status by UNESCO. After a warming lunch at Albert Dock, which has a multitude of good restaurants, along with a branch of the Tate Modern Museum, we had an hour to kill before beginning our National Trust tours of the childhood homes of Paul McCartney and John Lennon, and so we wandered for a bit around the Dock, and alongside the Mersey Estuary.

Like so many of the Liverpool waterfront structures that were erected between the mid 1800’s and the early 1900’s, The Albert Dock, built in 1846, demonstrated the cutting edge of architecture and engineering. Its deep, enclosed harbor allowed ships to unload their valuable cargoes directly into the first non-combustible warehouses in the world; storage areas that were built entirely of cast iron, brick and stone, with not a plank of structural wood. During WWII

the British Admiralty used the Dock as a base for the Atlantic Fleet, but the complex was badly damaged during the air raid blitzes of May 1941.

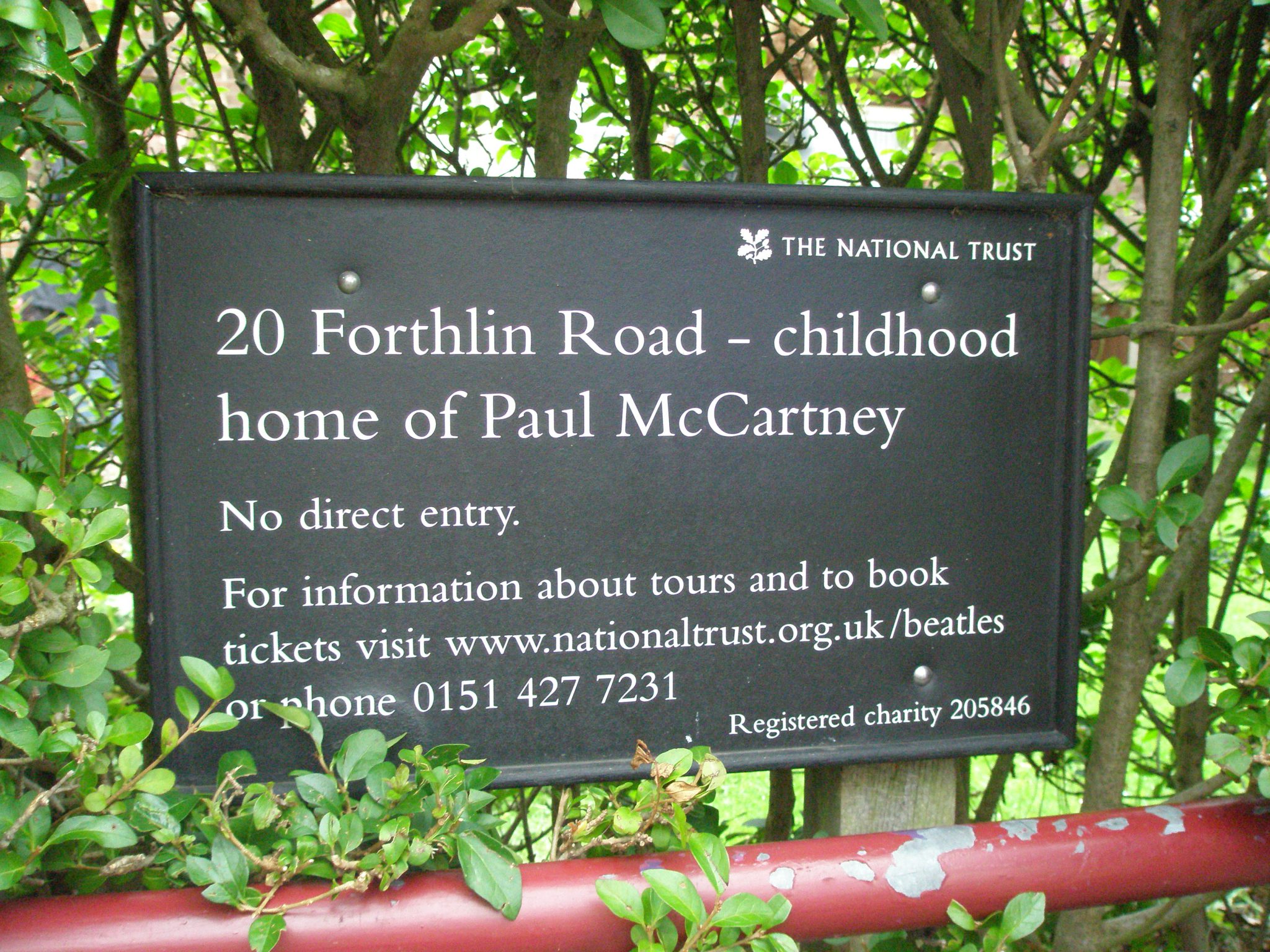

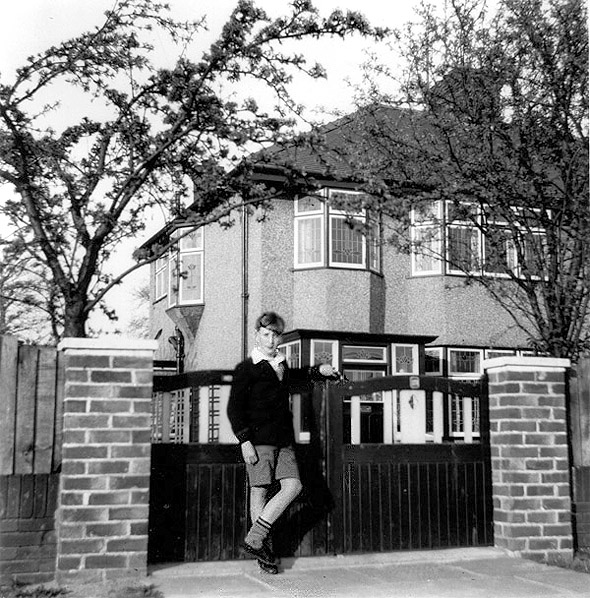

Next came our visits to the childhood homes of Paul McCartney, and John Lennon. Both houses are owned by Britain’s National Trust, which allows only 14 visitors at a time to enter those properties. Of course Anne, being her always-organized self, had long ago reserved our tickets for these intimate house tours. After a rather goofy 30 minute-van ride from Albert Dock to Liverpool’s inland suburbs, as we passed landmarks such as Penny Lane and Strawberry Fields, and during which Beatles music was piped through the speakers, we arrived at 20 Forthlin Road, where the McCartney family lived from 1955 until 1964.

Forthlin Road is part of the Mather Avenue estate, a complex of 330 public housing units that were built between 1949 and 1952, several miles to the south of Liverpool’s decimated City Centre, were the May 1941 Blitz had killed more than 1300 people.

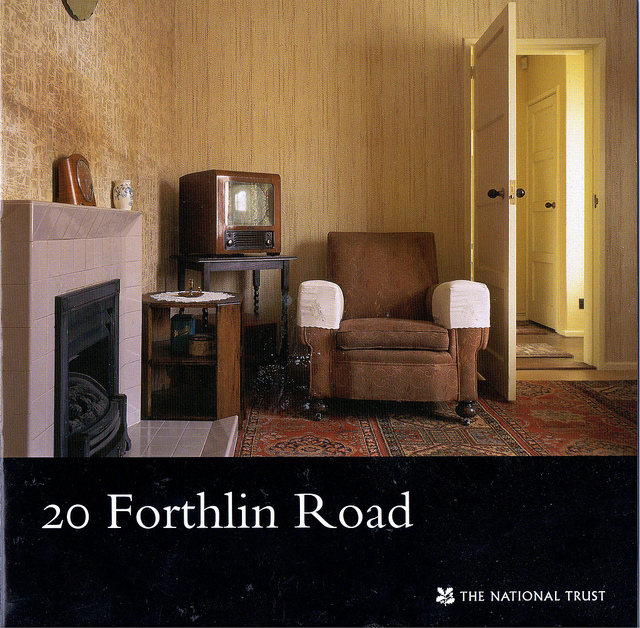

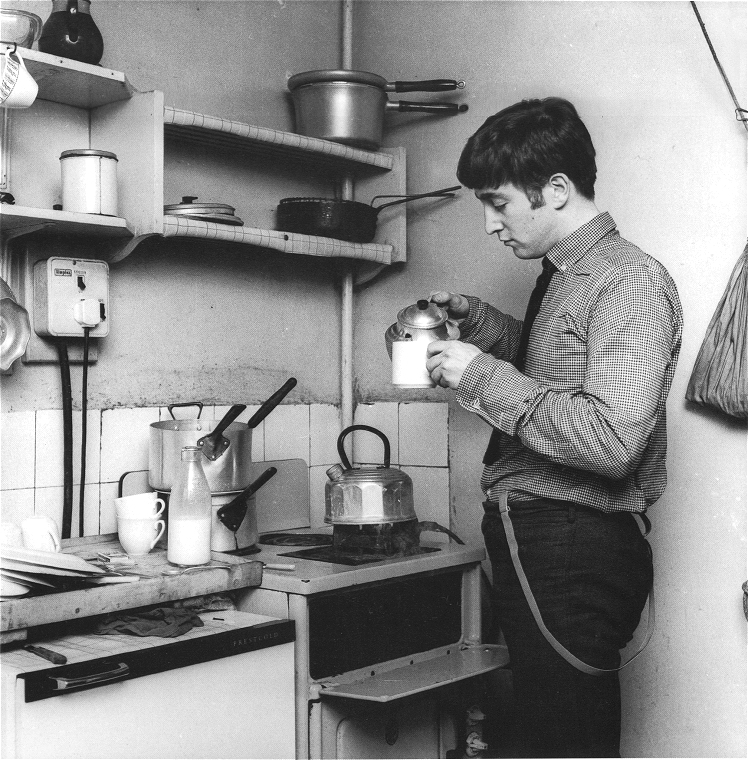

As the City Centre was cleared and rebuilt, urgently-needed housing was constructed on the fields surrounding the City. In 1955 the McCartneys (parents Mary and Jim, 13-year-old Paul, and 11-year-old Mike), who’d been living in the less pleasant surroundings of the farther-removed Speke Estate, were delighted to become renters of a two story mid-terrace house (model number “SB5-Intermediate Type Standard Building 5” ) which had been designed by Sir Lancelot Keay (what a NAME!), Liverpool’s City Architect.The Forthlin Road house was, in Paul’s words, “a pleasure to live in,” because, among other fine qualities, it included an indoor toilet, an amenity which their Speke house had lacked (at Speke, each back garden had an outhouse). Into these compact spaces, which seemed impossibly cramped for our group of 14, the McCartneys spread out, but their happiness was shattered within a year, when Mary died of breast cancer.

The National Trust doesn’t allow interior photo-taking, but images of the McCartney home (which includes a front hall, a living room, dining room, and kitchen on the first floor; 3 bedrooms and a bathroom on the second; and a walled, back garden where the lavender hedge that Jim McCartney planted still grows) are readily available on the web.

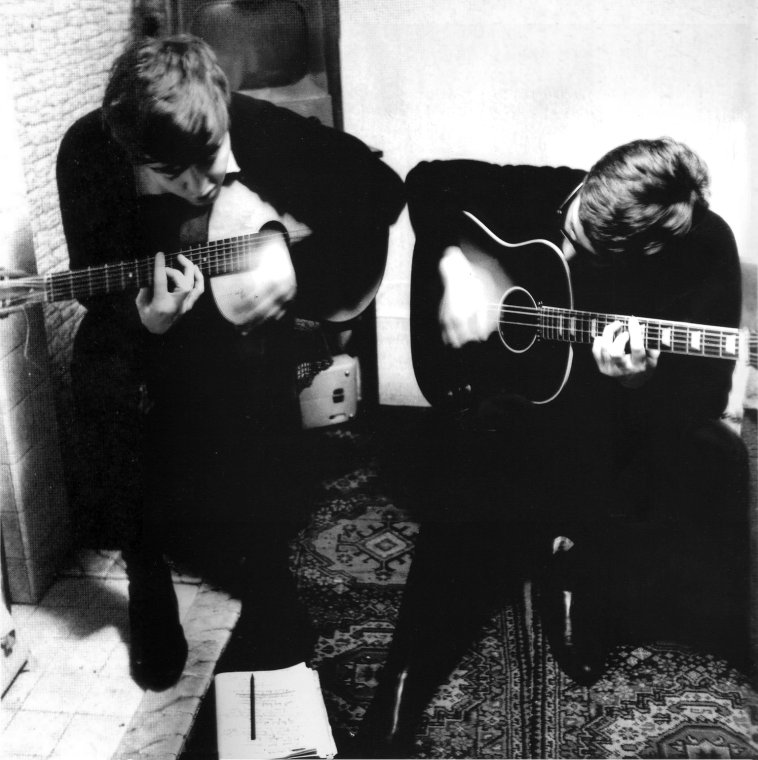

All interiors have been restored to their McCartney-era appearance. The living room walls are once again papered in four patterns (Chinese, abstract, willow-pattern and stone-effect): designs which were chosen by the young McCartney brothers, based upon whatever end-rolls of paper could be acquired for a small price. The floors, using the same, frugal approach, are carpeted in a jumble of remnant patterns. An upright piano and a few armchairs fill the living room (brother Mike’s drum kit clogged the dining room) and it was here, on most afternoons, that McCartney and his friend Lennon twanged cheap guitars and wrote their first songs together. Because Paul’s father was off working, the boys could make all the musical ruckus they liked (there’s no record of what the neighbors thought), and so the earliest Lennon-McCartney compositions, like “Love Me Do,” were born. Neither boy could read music, but their procedure for judging song quality worked very well. Paul said “We had a rule that came in very early on out of sheer practicality, which was, if we couldn’t remember the song the next day, then it was no good.” The Beatles were

sensible chaps.

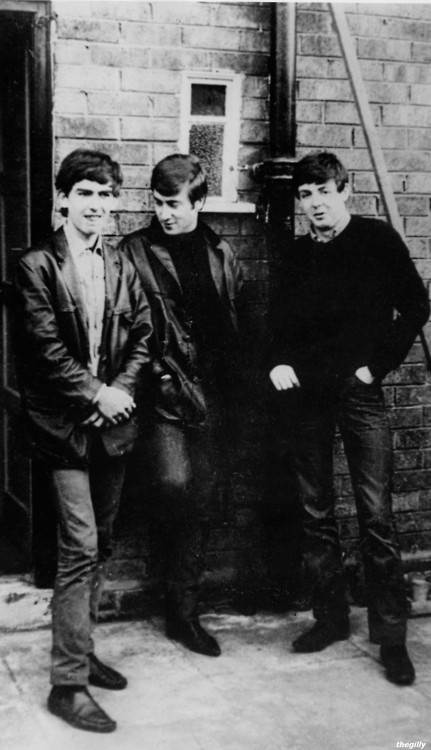

George Harrison, John Lennon & Paul McCartney in the back garden at Forthlin Road. Behind Paul’s head is the drainpipe that he’d climb to the upstairs bathroom window, as his 13-year-old-self snuck back home from late-night jaunts that his mother would have frowned upon.

Pausing for a moment to mention George Harrison, the other gifted songwriter in the group… 12 Arnold Grove, the Liverpool house where Harrison was born, and where he lived until he was 6 (his family thereafter moved to

the Speke Estate, the very same council estate that the McCartneys moved away from), is privately owned, and its beleaguered owner would like nothing more than to be forgotten by the legions of Beatles fans who idle their taxis at his curbside. The Liverpool City Council has begged to place an English Heritage plaque on the building, to no avail. Here’s where George began; but just look at this picture, and please leave the homeowner in peace!

Our next stop was Mendips, the house where John Lennon went to live with his Aunt Mimi in 1945, when he was 5 years old. Lennon’s parents were dysfunctional, to say the least, and Mimi made it her life’s mission to provide a loving and stable home for her adored nephew. As Lennon later commented “I lived in the suburbs in a nice semi-detached place with a small garden and doctors and lawyers and that ilk living around. I was a nice clean-cut suburban boy. I’d say I had a happy childhood. I came out aggressive, but I was never miserable. I was always having a laugh.”

Lennon and McCartney shared a tragic bond: within a year’s time, each teenaged boy’s mother had died. But their musical bond transcended their family sorrows. The story of how on 6 July 1956, Paul McCartney went to a church fete in Woolton in search of pretty girls, and instead found John Lennon, who was performing (not very well) with his skiffle band the Quarry Men, has become legend. Realizing that having someone around who could actually tune and play a guitar might be helpful, Lennon invited McCartney to join his band, and so the germ of what eventually became the Beatles began.

Aunt Mimi was quite particular about who she allowed into her home, and by which door entries were made. Our small group was directed to enter Mendips through the back door, as were all of John’s friends. Mimi’s first thought upon hearing that John had made a new friend, whose family lived in public housing,was something along the lines of: “Harrumph….that boy CANNOT be good enough for my John!” But Paul unleashed the McCartney charm, and was soon a welcome guest…but only so long as he didn’t make too much musical noise. Mimi soon banished the boys to the front entry porch, where they worked on their singing and harmonies. As I’ve mentioned, the problem of musical disturbances was solved, once John and Paul retreated to Paul’s empty home for their afternoon song-writing sessions.

Dining Room. When money was tight, Mimi would take in boarders, who’d rent her bedroom, while she’d sleep on a portable cot in the Dining Room.

In 1965, when Mimi decided to retire to Dorset, John begged her to keep Mendips, but she wanted to sell. Only because of Yoko Ono’s generosity is Mendips now owned by the National Trust. Here’s Ono’s explanation:

“Liverpool meant a great deal to John. It all started in Mendips. Whenever I came to Liverpool with him, we would drive along Menlove Avenue, and he would point at the house and say ‘Yoko, look, look. That’s it!’ When I heard that Mendips was up for sale, I was worried that it might fall into the wrong hands and be commercially exploited. That’s why I decided to buy the house, and donate it to the National Trust. Everything that happened afterwards germinated from John’s dreaming in his little bedroom at Mendips, which was a very special place for him.”

Our 2 ½ hour excursion into Beatles history over, we returned to Liverpool’s waterfront, where we wandered until darkness fell.

The Three Graces: from left to right: 1) The Royal Liver (pronounced LIE-ver) Building, with its 2 fabled birds who watch over the city, and over the sea.

2) The Cunard Building. 3) The Port of Liverpool Building.

The two enormous hammered copper cormorants that grace the towers of The Royal Liver Building measure 18 feet high by 10 feet long, and have wing spreads of 12 feet. Officially, the birds are meant to be guardians of the City. One bird watches over the people on the land, and the other over the sailors upon the sea; if either bird were to fly away Liverpool would cease to exist. But Liverpudlians ascribe more colorful roles to their beloved birds, and prefer to say that every time a virgin walks across the Pier Head, the Liver Birds flap their wings (and you’ll notice the wings NEVER flap). How can one NOT love these people, and their city?

September 21st, back to The Midlands.

After our marathon visit to Liverpool, prudence dictated that we sleep until respectably late hours, and then spend the remainder of Friday a bit closer to home. We gathered at Anne and David’s, and inspected Anne’s exquisite back garden (all photos of which were taken by Anne)…

…and then proceeded to Julia and Roger Aldridge’s for tea, where Julia and her cats Tim and Henry gave us a tour of her yard (photos of which are also Anne’s):

As you can see, my British friends make sublime gardens!

Our plan for the afternoon was a visit to the ruins at Witley Court,Great Witley, Worcestershire. Inevitably, since the buildings we’d be

wandering through are roof-less, the skies, which had been reticent all morning, finally unleashed drenching rains: the afternoon would be soggy.

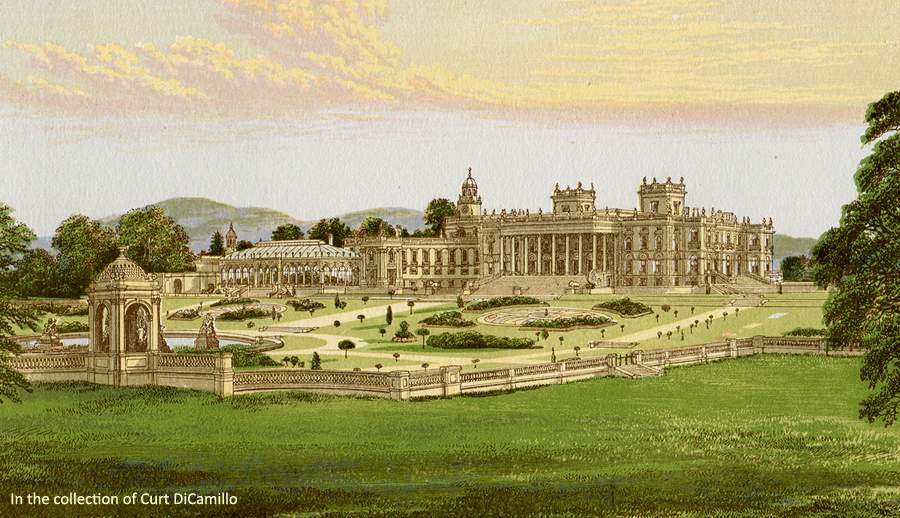

Rather than rewrite what has already been well-stated, I quote from the English Heritage guidebook, “Witley Court” :

“Once one of England’s great country houses, Witley Court was largely gutted by fire in 1937. The owner, Sir Herbert Smith, decided not to rebuild, but to put the estate up for sale. Witley was never lived in again and was subsequently stripped and abandoned. Yet, as a ruin, it remains deeply evocative. Today it offers a rare opportunity to see the bones of a mansion that has grown over the centuries, from a substantial Jacobean house, based upon a medieval manor house, through expansion under the first Baron Foley and his son in the 1720’s and 1730’s to the addition of two massive porticos by Regency architect John Nash. It finally reached its peak of grandeur in the 1850’s with the extensive remodeling commissioned by the first earl of Dudley from the architect

Samuel Daukes. Lord Dudley’s immense wealth, generated largely by his industrial enterprises in the West Midlands, enabled his family to live an extraordinarily opulent life. It also funded the creation of an ornate formal garden at Witley designed by William Andrews Nesfield, the leading garden designer of his day. An army of servants was involved in servicing the property and family, further swollen during the lavish house parties attended by the Prince of Wales (later King Edward VII) and his circle.”

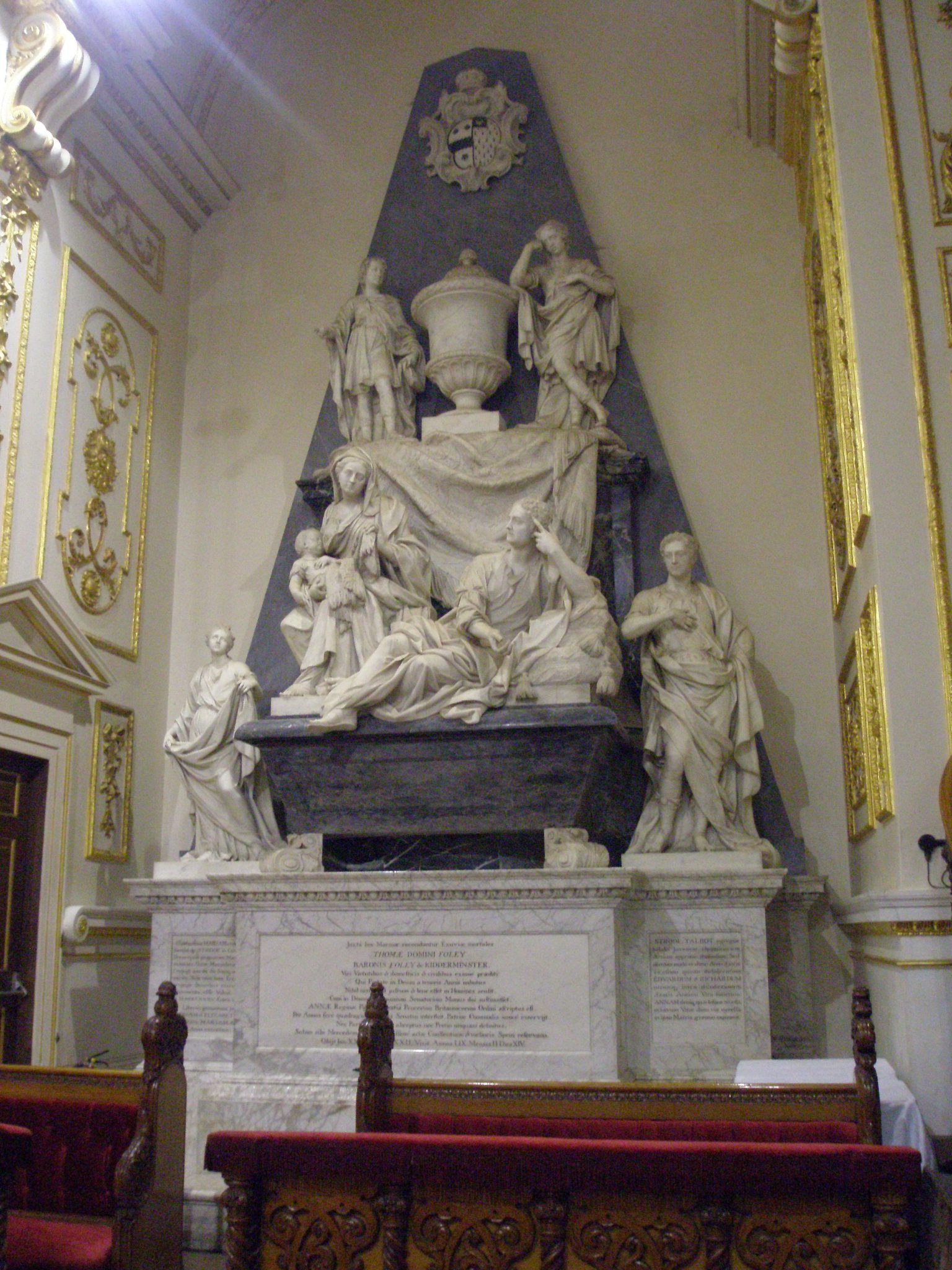

We first popped inside the Witley Parish Church, a still-functioning place of worship that’s attached to the manor house ruins. The Church is a rarity in England: the baroque style of its interior is more typical of Italy and southern Germany.

Leaving the Church, we approached the magnificent ruins.

Fountain in ACTION. Perseus and his winged steed Pegasus are riding to Andromeda’s rescue. Sea monsters snap at their heels, but the hero and his lady fly off, in a spray of water! How’s THAT for watery entertainment. The fountains are activated, once every hour, and run for 20 minutes. AG

East Parterre. During Witley’s glory days, when balls were held the East Parterre was illuminated with hundreds of colored lanterns. But the color I find most beautiful here is the auburn soil, in the distant, just-plowed fields.

The Fountain of Flora, in the East Parterre. Flora herself, whose statue once crowned the composition, was vandalized some years ago. AG

Janet at rest by the Flora Fountain, with the remains of the 4 Tritons (fish-tailed humans) guarding her

Ballroom Wing, as seen from East Parterre. The Ballroom was 69 feet long, decorated in Louis XV style, and illuminated by 8 enormous crystal chandeliers. But after looking at period photos of Witley’s overly-gilded rooms, I think that the drenched bones of the House that I saw on this rainy day were the most beautiful aspect of the place. AG

These photos of Witley’s ruins say it all: rarely have I been to a place that so exemplifies the concept of sweet melancholy.

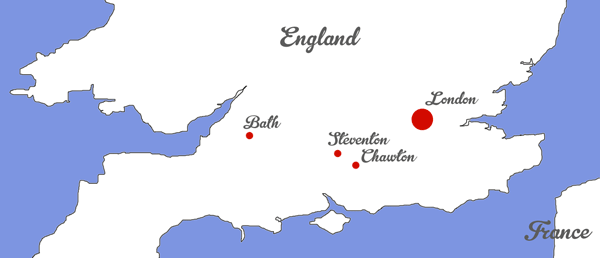

September 22nd. A long drive from the Midlands to the South Coast of England to see Jane Austen’s House at Chawton.

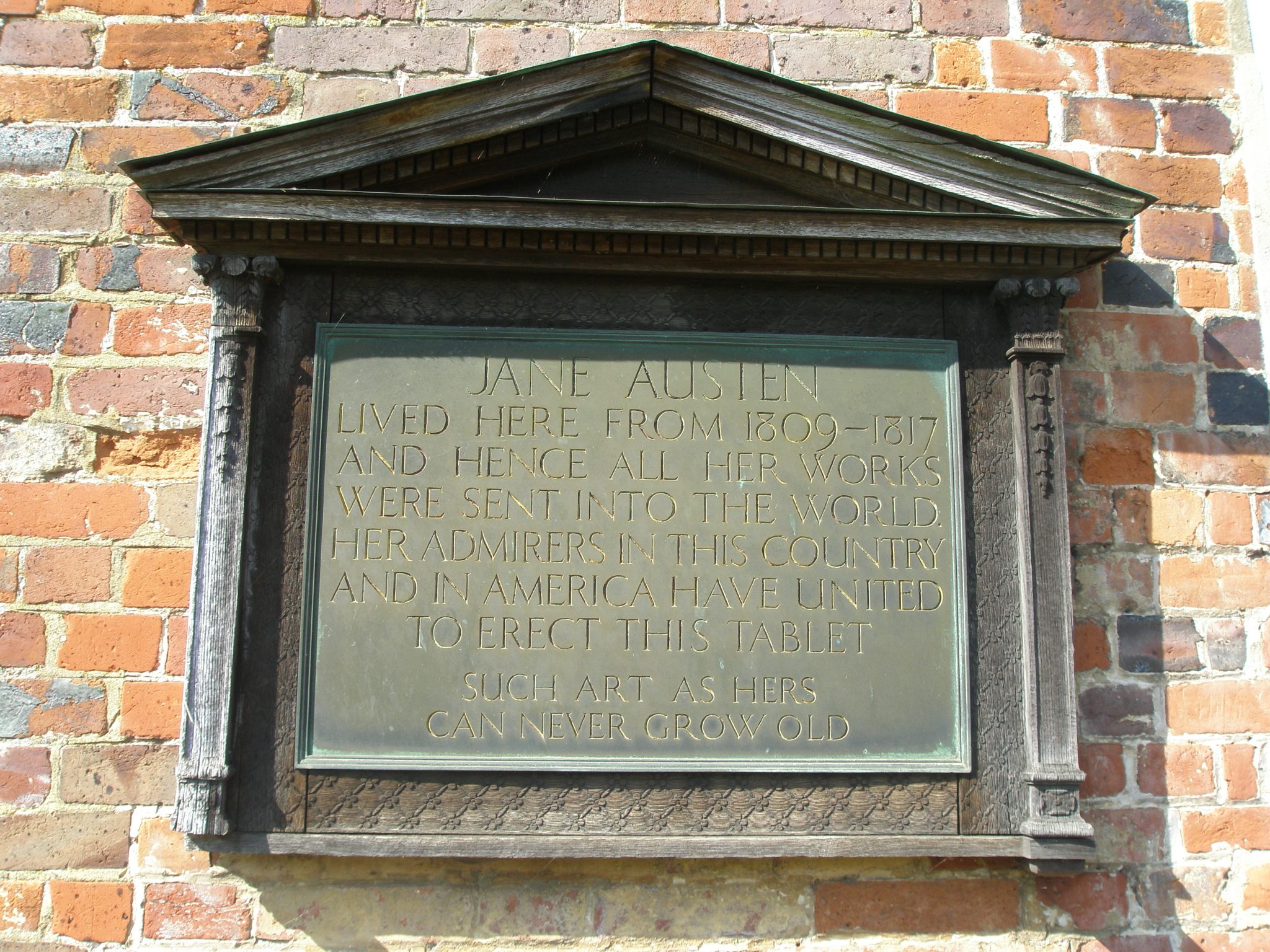

With Friday’s rain and Witley’s grandeur in our rear view mirrors, we set out on a warm, sunny Saturday for Chawton, where Jane Austen

spent the final eight, and most literarily productive years of her too-short life (she was born on 16 December 1775, and died on 18 July 1817).

I’ve written previously and at length about Jane Austen, on behalf of the Jane Austen Society of North America, so I’ll not go into huge detail here about her life and works. At a future time, I’ll publish an Armchair-Traveler’s-Chapter about Jane Austen and Bath, England.

But on this Saturday, my purpose was not to learn about her life of the mind.Instead, I wanted to see her kitchen, and her garden and her sitting room…and I did see where she kept her chamber pot. There’s no privacy in this world, not even in death, although Jane’s sister Cassandra did her damndest to protect Jane’s most intimate observations about her world. After Jane died (probably of Addison’s Disease), Cassandra burned much of her collection of Jane’s letters, and although the historian in me moans at such a loss, the sister in me says “Good for you, Cassandra!”

Early in 1809, Jane’s brother Edward offered his sisters and mother the use of a large cottage in the village of Chawton. The ladies, who’d been essentially itinerant since 1805, when Jane’s father George Austen had died, gratefully accepted Edward’s proposal.

After a three hour drive, Janet and Anne and David and I arrived in Chawton Village, where we restored ourselves with tea and lunch on the sunny terrace of Cassandra’s Cup, the café directly across from the Austen House.

Note the large, bricked-in window under the low arch on the first floor of the House. Before the Austen ladies’ arrival, that space had been a large window in the parlor, which looked out upon the main road.Apparently, Brother Edward didn’t want the people in the stagecoach that passed daily to be able to peer at his womenfolk, and so he had the window bricked shut. Jane, however, had the last word about how much of the world she wanted to see, or be seen by: she simply placed her writing table by the dining room window, which is to the right of the front door.

Released from the social whirl imposed by her life in Bath, Jane’s creative juices obviously coalesced, and, sitting at her little table (which is not much bigger than today’s laptops) in this quiet village, she revised her manuscripts for “Pride and Prejudice,” “Sense and Sensibility,” and “Northanger Abbey,” and wrote “Mansfield Park,” “Emma,” and (my favorite) “Persuasion.” As I walked through the Chawton house’s plain, light-filled rooms, I imagined Jane in those same rooms: looking serene, but also driven by a quiet fever of thought and inspiration as she laboriously transferred her ideas with quill pen and ink onto paper. That laborious quality was made plain by the display in the Kitchen which described how Austen had to make her own writing ink. I also tried writing with a quill pen….NOT an easy task if one wishes not to dribble large ink blots across a page.

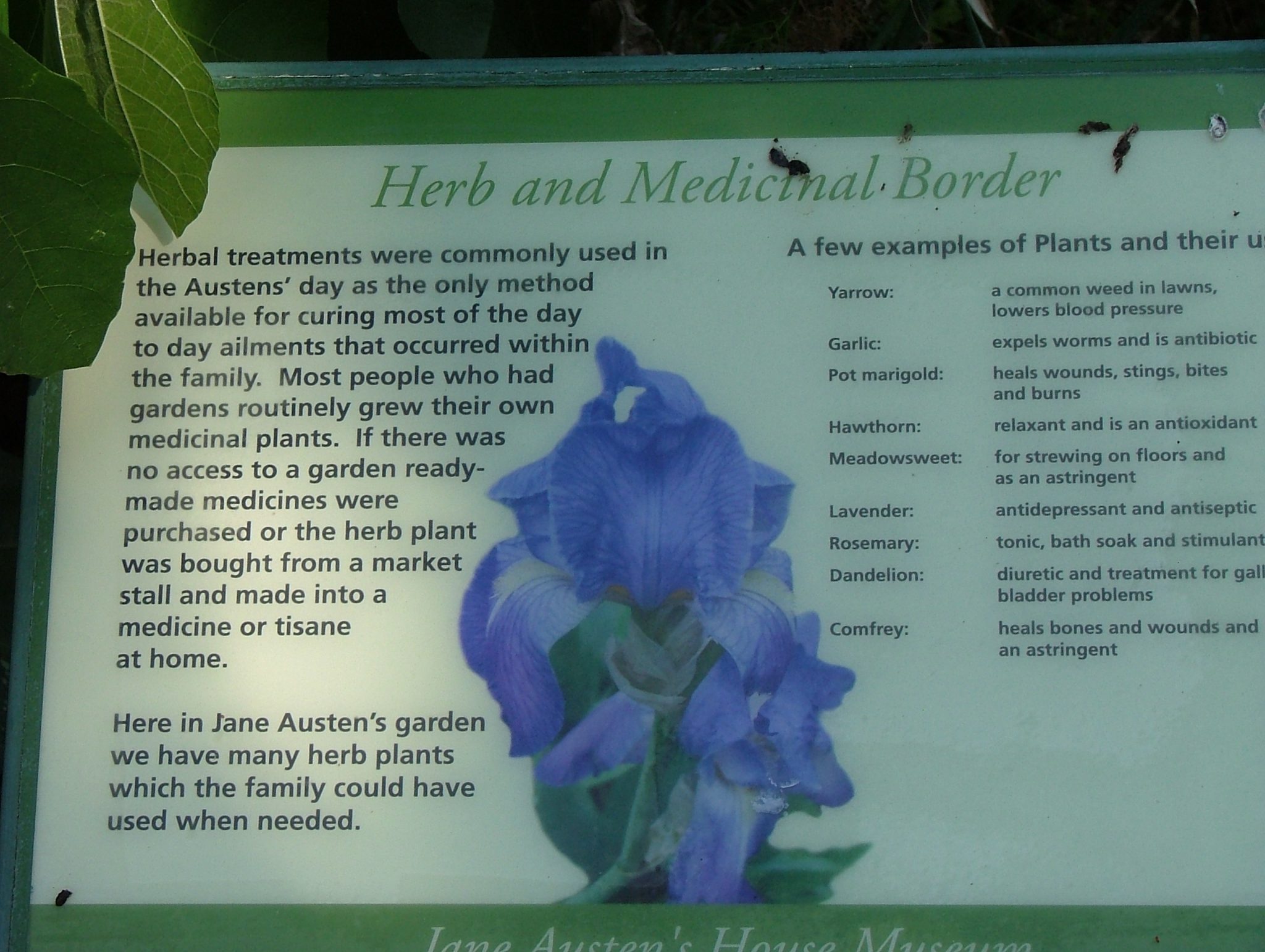

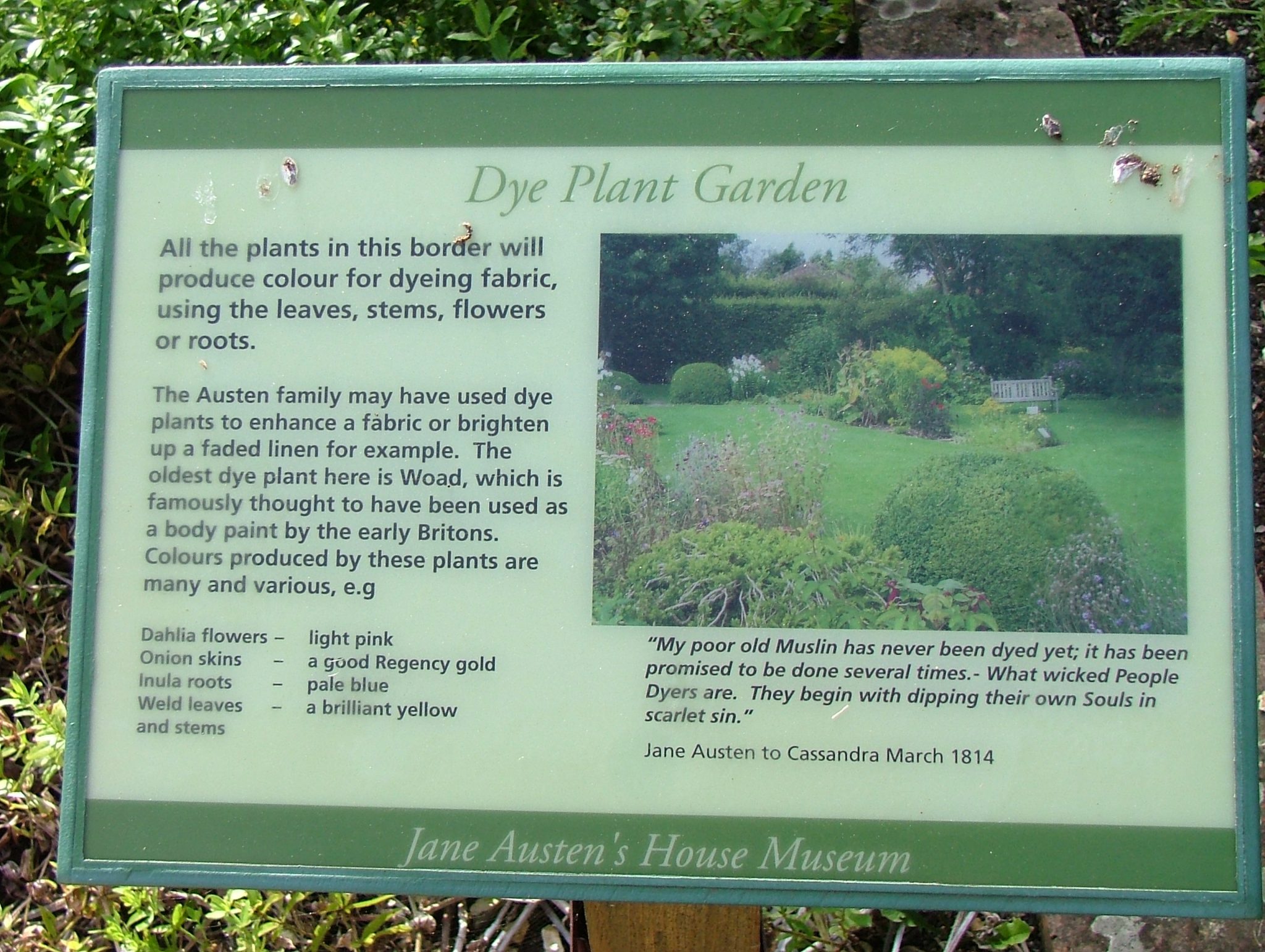

Our Self-guided tours of the House began with a largely useless and amateurishly-done video presentation about Austen’s life. Too much of the global Austen-Adoration has become cultish, and silly, with much romanticizing about the routines of Regency-Era life. But once freed of that introductory interlude, I found the un-rushed house-wandering that followed to be lovely, and illuminating.

In a service courtyard, the first building we encountered was the Bake House.

Moving then toward the back of the house, we entered the gardens.

As with most of the House’s rooms, the Kitchen is flooded with natural light…

…but, thanks to brother Edward’s decision to brick shut the largest window in the Main Parlor, the Parlor, now with a single window, is the darkest room in the House.

The door separating the Dining Room from the street-side Entry Hall squeaked. Jane refused to oil the door hinges, because the squeaking alerted her that people were about to invade her space, and so, given notice of the advancing visitors, she had time to hide all evidence of her writing. Austen’s first novels were published anonymously, attributed only to “A Lady.” For most of her life, her novel-writing activities were known only to her family. I always think of Jane as Janus, with her two faces: the one she presented to her immediate World, and the other she kept for Herself.

Jane and Cassandra shared a bed for all of their lives. They must have been diminutive ladies, because this bed isn’t wide:

I’ve always suspected that this drawing of Jane that her sister made was more a record of Cassandra’s having gotten up that day on the wrong side of the bed,than a record of Jane’s peevish countenance…

…but perhaps this silhouette, with Jane’s nose looking very much like that of her father’s, is a more accurate representation of her appearance:

Along with my obvious pleasure at seeing the rooms where Jane lived, the primary thought I took away from my afternoon at Chawton was that Jane Austen did EVERYTHING with care: she excelled at the ancient craft of lace-making; her hand-stitching on quilts is almost invisible; her tiny handwriting, executed with clumsy tools, was nonetheless artful. Her qualities of mind matched her sharp eyes and deft hands, and so her writing, though astounding, seemed a tiny bit more INEVITABLE, once I’d seen the care with which she handled the less-obviously creative facets of her life. Whatever her handiwork, Austen was almost always busy applying her razor-sharp skills.

There’s no explaining a genius. Perhaps only an excess of frontal lobe folds is what it takes for such creatures to occasionally appear? But, as Simone de Beauvoir said, “one is not born a genius, one becomes a genius.” We cannot exist apart from our environments, and so my visits to Liverpool, and then to Chawton, gave me much new to wonder about how the combined genius of Lennon and McCartney (only as partners did they perform with genius), or the singular genius of Austen (the mere thought of TWO Janes is terrifying), might have been energized and transformed by the distinctive characters of the places they lived. These mysteries, which can never be answered, are the things that periodically tease me away from the beautiful home I’ve created for myself, and out into the World.

During this journey that I’d begun in late August, I’d had the privilege of continuous, daily exposure to stunningly beautiful places, in Italy and in England. I’d visited estates and gardens and cathedrals and palaces and museums and cities of incomparable richness. But, somehow, standing in the McCartney family’s humble living room (a place totally lacking in physical beauty in which sublime songs were conceived), or lingering by Austen’s little writing table (an unremarkable spot where profound stories about the power of human emotion were crafted), reminded me that the greatest cathedrals are those that humans cannot see, but which their minds and souls contain.

Next: The Glories of Greenwich, and the Splendors of Hampton Court Palace.

Copyright 2012. Nan Quick–Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

5 Responses to Contemplating the Genius of Place & The Places of Geniuses: Liverpool,Ruins at Great Witley,Chawton