I really wanted to call this Armchair Traveler Chapter “Jane Austen’s Bath.” But holding forth about Jane’s bathing habits would have given me ammunition for a brief and not very interesting article. So, instead it’ll be “Jane Austen AND Bath.” I’ll try to describe the City as it was during the times when she lived there, and I’ll show you many of the locations that she used in two of her books. Happily, the built world of today’s Bath is largely unchanged from Jane’s time. Over the past two centuries the City’s fame has protected it from indiscriminate “improvements,” and so visiting Bath today gives a fairly good impression of what Jane’s days there might have been like.

If you’re reading this, it’s likely you’re Austen-informed, and have thus read NORTHANGER ABBEY and PERSUASION, which are called Austen’s Bath novels.

On May 28th, 2011 I had the pleasure of spending an afternoon in Bath. Of course, in England, the weather has a mind of its own, and storms from a place called “Bill’s Mother’s” descended. Here’s how it is with Bill: the locals always say bad weather is blown in from a mythical place called “Bill’s Mother’s.” I thought you should know, just in case you go to Bath and people start talking weather. On that Saturday my British friends and I were rained upon, blown about, and generally frozen; late May felt like early March. But I’d asked Anne and David and Janet (who you’ve met in my earlier Armchair Traveler pieces) to make the long round-trip drive on the traffic-jammed M5 with me from the Midlands down to Bath, expressly so I could make the following words REAL to myself:

“The Crescent,” “Milsom Street,” “Pulteney Street,” “The Pump Yard.” I also wanted to clear my confusion, once and for all, about all those infernal ROOMS that Austen’s characters scurried between: the Upper Rooms, or the New Assembly Rooms; the Lower Rooms; and the Pump Room. Even though my time there was short, and the weather awful, I managed to get a sense of the lay of the land, which is what I’d like to share with you.

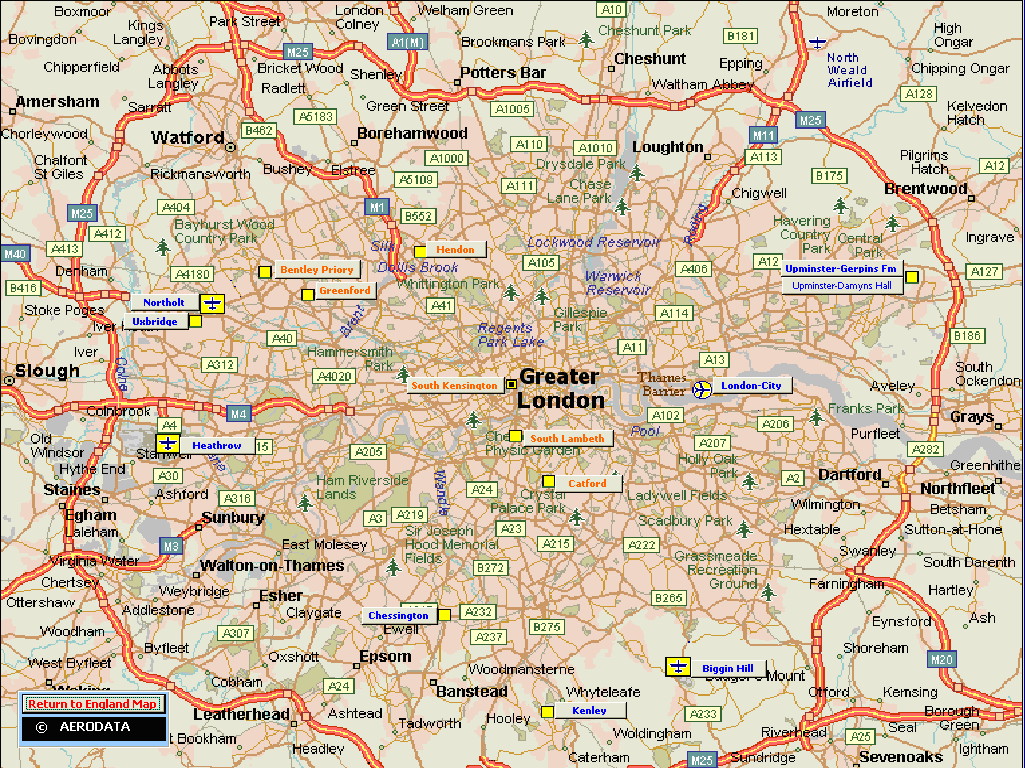

Since good explorations always begin with maps, we’ll orient ourselves by looking at Southern England.

In Jane’s time, the 116 mile journey by coach and horses from London to Bath was a two or three-day ordeal. As it was, our trip from the Midlands took almost three hours. As we left the highway and approached Bath, we were smack dab in the middle of postcard scenery.

Bath is settled in a river valley, and is approached over high rolling meadows, filled with grazing animals. From the ridgeline east of Bath, we could see for miles and miles; all the way to Wales toward the northwest. Jane’s journeys to Bath were not terribly arduous; the 60 mile trip from the Austen home at Steventon Rectory took one long day, which would have exhilarated rather than exhausted any young woman who was eager to see the famous spa town. Jane made her first two short visits to Bath in 1797 and again in 1799. Her family had strong ties to the City: her mother had relatives there and Bath was where her parents had met each other, most certainly in those many and confusing Rooms that I’ll soon describe. By the mid-to-late 1700’s, Bath’s combination of busy social halls, gleaming new buildings, and ancient thermal springs had made the City the most fashionable vacation spot in England. Bath was a sterling example of what we now call urban renewal.

My purpose here is not to give the long history of an old City, but anyone seeing Bath for the first time has to understand that although its scores of aged-looking limestone buildings are relatively new, its origins are ancient: it was established by the Romans in 60 A.D. after they discovered its healing waters. Like all ancient places, its fortunes had risen and fallen, and by the early 1700’s Bath had devolved into a ramshackle mess of shabby wooden structures, muddy alleys and mineral-water springs, all radiating outward from the splendid Gothic cathedral of Bath Abbey. The city that Jane knew was the brainchild of four nervy and profit-seeking 18th century men who’d taken bold steps to reinvent and rebuild the jumble into a showplace of neoclassical architecture. Innovative circular and crescent-shaped street layouts designed by the architects John Wood the Elder and his son imposed graceful order upon blocks of new townhouses and allowed inspiring views of the hilly countryside. Limestone from quarries owned by the businessman Sir Ralph Allen lent a pleasing harmony to acres of new construction, and generous flagstone walkways somewhat lessened the mud of wintertime. Social savvy exercised by the gambler Beau Nash enticed crowds to glittering new ballrooms, where he organized new rituals of behavior. These men invented a City that for 50 years remained Society’s favorite place to go during the long Winter Season, which ran from October to May, and which–to my mind–is the worst time to visit, due to the constant rain. Despite its weather, Bath had something to keep everyone indoors and happy. By 1790, health-seekers could be comforted by its hospital, 18 physicians, 13 surgeons, 25 apothecaries, and numerous hot spring pools. At the height of Bath’s popularity, the over 20,000 visitors who arrived each year to join its 40,000 permanent residents had theatres, concerts, dances, teas, parks, first-quality foodstuffs and subscription libraries to help them fill their days. And the length of a sojourn spoke to the degree of one’s importance. Anything less than a 6 week visit branded the visitor as a person of no significance whatsoever. Jane’s first extended stay in Bath, in May of 1799, had the unfashionable duration of four weeks and 5 days. It also occurred at the beginning of the City’s gradual decline; a royal whim had redirected the most-fashionable of the British away from Bath’s mineral waters toward the seaside at Brighton. But Bath remained the holiday-of-choice for the less-than-wealthy, and was certainly a cultural, as well as a marriage-market mecca, for anyone accustomed to a quiet life in the country.

First-time visitors almost always gravitate upwards and away from the crowded City Center, which hugs the banks of the River Avon. Whether you’re a student of architecture, or a fan of the many movies that have been filmed there, the lure of walking alongside the world-famous Royal Crescent is strong. After we’d shuttled from the out-of-town parking lot into the City Center, my friends and I headed directly uphill on Gay Street.

All of my pictures are strictly truth-in-advertising: no postcard-blue-skies here for you now.

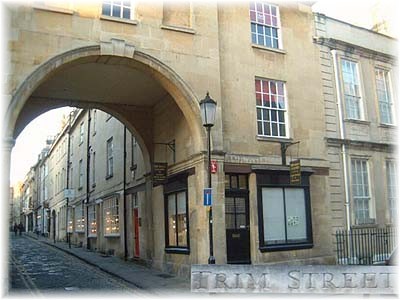

This photo shows the uppermost part of Gay Street, with the trees of Queen Square at the bottom of the hill, to the right. At various times in Bath, Jane lived in this part of town: on lower Gay Street, on Trim Street, and also on Queen Square, and so she would have done much walking up and down Gay Street, which is the most direct route to the Crescent.

Upper Gay Street meets the Circus…

… which is a residential complex that Jane visited many times when her friends Marianne and Jane Mapleton lived there, at #11.

The Circus consists of three terraces of tall, narrow houses that curve around a circular space whose diameter of 318 feet deliberately matches that of Stonehenge; John Wood the Elder was nothing if not mindful of history, and the Circus has also been compared to the Colosseum in Rome, only turned inside out. Although the Circus’s fame is equal to that of the Crescent, Jane never used it as a location in her novels.

Notice the elaborate carvings representing the arts and sciences on the Doric Frieze above the front doors. There are 528 individual carvings and it is said that no two are the same. The Circus was built between 1754 and 1766, at the beginning of the great push to reshape Bath in the most elegant fashion. No wonder the Circus took 13 years to build. Remember these beautiful details when we get to pictures of The Royal Crescent, which was constructed 10 years later, by John Wood the Younger.

From the Circus, we continued upwards toward the Crescent, via Brock Street, just as the Tilneys did on their walks in NORTHANGER ABBEY…

…past Margaret’s Place…

…and to the corner where Upper Church Street meets Brock Street…

Number 1 Royal Crescent, is the first of the 30 houses which make up the elongated ellipse.

Originally named the Crescent (the Royal was added after a prince and a duke lodged there), the Crescent was completed in 1775, the year of Jane’s birth, and is thought by many experts to be the first residential crescent to be built in the world. These were the

most coveted Bath lodgings, and commanded the best views across the valley of the River Avon. At the end of the 18th century, no houses interrupted the view from the Crescent down to the River. Jane’s uncle and aunt, the Reverend Edward Cooper and his wife Jane, lived in fine style in Bath, and took one of the best houses available in the Crescent, at #12. It is recorded that Jane’s sister Cassandra stayed at #12, but we don’t know if Jane also did.

This is a passage from NORTHANGER:

“As soon as divine service was over the Thorpes and Allens eagerly joined each other; and after staying long enough in the Pump Room to discover that the crowd was insupportable and that there was not a genteel face to be seen, which everybody discovers throughout the season, they hastened away to the Crescent to breathe the fresh air of better company.”

The folks in NORTHANGER ran up the hill, just as my friends and I did, but they were not met with our same blast of cold and sideways rain! Suddenly, the higher regions of Bath, much sought after in Austen’s time and still today, seemed less attractive than the lower, less blustery parts of town, and we rushed past the Crescent faster than we’d planned.

Remember the exquisite detailing on the façade of the Circus. The Crescent, however Royal, was clearly made in a far greater hurry, and without the same abundance of funding. The columns are unadorned. The pediments which one would expect in neoclassical architecture do not appear over

windows, and, more surprising, are missing over doors. Up close, the Royal Crescent seems incomplete, or perhaps only starkly modern. There are also basement units, with charming entry courts, but I wondered if they get flooded when it rains.

If the day had been sunny and warm,perhaps I would have longed for a stay at the five star hotel there, but all I could think of was how to remove myself from the Crescent, which invited the wind like a sail. We continued to the far side, past end unit #30…

…over beautiful but slippery pavements…

…and headed downhill past The Marlborough Buildings…

…to the Gravel Walk that spans the width of what were called the Crescent Fields, with the Royal Crescent above. Remember this scene in

PERSUASION with Anne and Wentworth:

“Soon words enough had passed between them to decide their direction towards the comparatively quiet and retired gravel-walk, where they once again exchanged those feelings and promises which had once before seemed to secure everything; but which had been followed by so many years of division and estrangement.”

We used the Gravel Walk to head back toward the Circus, because it was time to find the New Assembly Rooms, alternately called the Upper Rooms. We reached Bennett Street…

…and the corner of the Assembly Rooms, and once away from the open spaces of the Crescent, were sheltered from the wind. Bath suddenly became a nicer place to be, despite the clouds, and my brain unfroze long enough to think of Catherine Moreland’s first dance in Bath.

“The important evening came which was to usher her into the Upper Rooms….they did not enter the ball-room till late…as for Mr. Allen, he repaired directly to the card-room, and left them to enjoy a mob by themselves…everybody was shortly in motion for tea…and when at last arrived in the tea-room, she felt yet more the awkwardness of having no party to join.”

So these were the Rooms! And they were closed for a private function, as we learned they often are! The Assembly Rooms now mostly earn their keep as a venue for conferences and weddings. But I could imagine ladies gathering in the entry court, adjusting the high feathers of their headdresses.

Walking around the outside, the great size of the Rooms became apparent.

Balls were held twice a week and attracted from 800 to 1200 guests. Because the social whirl was so intense, both Upper and Lower Rooms (& more later about the Lower Rooms) held dances on different evenings so visitors would never have to miss one. Beau Nash was the first master of ceremonies to preside over the Rooms. Although there were special seats for peeresses and a rule that allowed time “for ladies of precedence to take their places,” Beau Nash reprimanded those who invoked social precedence on the dance floor and tried to prevent an atmosphere of exclusion…after all, IN-clusion was good for business…the more tickets sold for dance subscriptions, the better. Here’s a diagram of the Assembly Rooms.

Guests enter through a long, central hall, which is shown here in red. To their left is the Ball-room, shown here in blue.

Today’s fire codes don’t allow crowds of 1200 dancers; the Ball-Room’s official capacity is now 500.

To the right of the entry hall is the Tea-Room, a sunny space, facing south.

This was also known as the Concert-Room, and had an observation gallery. The fire marshal allows

300 bodies to occupy the space now, but we can be certain that, in Jane’s time, far more people crammed themselves in.

The Great Octagon, at the head of the entry hall, was used as a waiting area, and today holds functions for up to 200 people.

This is from PERSUASION:

“Sir Walter, his two daughters, and Mrs. Clay, were the earliest of all their party at the Rooms in the evening; and as Lady Dalrymple must be waited for, they made their station by one of the fires in the Octagon Room. But hardly were they so settled, when the door opened again and Captain Wentworth walked in alone. Anne was the nearest to him, and making yet a little advance, she instantly spoke.”

After gathering in the Octagon, Austen’s characters would have passed into the Tea-Room to hear their concert.

The Assembly Rooms are lit by a set of 9 chandeliers, made in 1771. They’re considered to be one of the finest sets to have survived from the 18th century. Each chandelier is an average of 8 feet high, and was originally lit by candles. At the start of the Second World War, they were put into safe storage, and fortunately so, because the Assembly Rooms were heavily damaged during the Blitz. During the belated refurbishment of the Rooms in 1991, the chandeliers were restored and returned to their original places.

Beyond the Octagon was the Card Room…

Card Room at the Assembly Rooms (with the same unflattering green hue on the walls that is shown in Cruikshank’s cartoon)

…where one could hunker down for a quiet game. Today’s capacity is 100 guests.

Between events, the Rooms are erratically open to the Public. Here’s the social world that Austen was

responding to when she wrote her novels about Bath, wonderfully satirized by the illustrator George Cruikshank in 1796.

After carriages dropped partygoers off at the Rooms, coachmen assembled to wait out the evening in nearby Stable Lane, which was recessed into a hillside. We headed in that direction, down narrow alleys…

…and down the steep incline by the Miles Buildings.

At this point in our afternoon visit, the need for hot tea become more pressing than seeing more buildings, so we walked down Gay Street, to the Jane Austen Centre at #40, which is in a house very similar to #25 Gay Street, where Jane, her mother and her sister lived for 6 months following the death of Mr.Austen. All the Georgian town houses on the street are alike: three stories high, and only three windows wide. The modest interiors are utilitarian and quite plain, with narrow staircases connecting the floors. Before the 20th century, each town house had access to generous garden space out back, but those spaces have since been built upon.

As you can see, there’s a dreadful mannequin that’s supposed to represent Jane outside on the front steps, but some German men were happy posing alongside her. I’m sure Jane would cringe at this, but that’s what being Austen Incorporated involves these days. Rosy-cheeked greeters dressed as country squires welcomed us to the building and directed us to the second floor tea room, where we warmed up and recovered with scones, clotted cream and jam.

After tea, we continued our explorations of the City, and made a quick detour to Queen Square…

…where Jane very happily lodged at #13.

This was where Jane stayed on her second visit to Bath. She was accompanied by her mother, and brother Edward, who had come to take the mineral waters. In May of 1799 Jane wrote to Cassandra:

“We are extremely pleased with our house; the rooms are quite as large as expected. Mrs. Bromley (landlady) is a fat woman in mourning, and a little black kitten runs about the staircase…I like our situation very much.”

In PERSUASION, one of the Miss Musgroves says:

“I hope we shall be in Bath this winter; but remember Papa, if we go, we must be in a good situation—none of your Queen Square for us!”

But at this stage of her Bath-visiting Jane Austen was clearly pleased to be there, even if Queen Square wasn’t one of the posh addresses. My friends and I then back-tracked uphill, to the head of Milsom Street, which is now Bath’s premiere shopping district.

In Jane’s time Milsom Street was also a fashionable place to live and shop. It was also where Austen placed many of her characters in NORTHANGER ABBEY and PERSUASION. In NORTHANGER, Austen settled both the Thorpe and Tilney families there, and in PERSUASION, Anne Elliot finds Admiral Croft admiring the windows of a Milsom Street print shop. More importantly, at Molland’s Sweetshop– #2 Milsom– Anne and Wentworth reconnect on a rainy day. Of course all those shops that Jane wrote about are long gone, but the buildings and paving stones on the street are still the same.

As most of Bath’s streets do, Milsom slopes downward toward the River Avon.

At the end of Milsom Street, we continued down Old Bond Street…

…toward the Royal Mineral Water Hospital…

…which to this day still specializes in the treatment of rheumatic diseases. In Jane’s time, it provided care for the impoverished sick who were attracted to Bath by the healing waters, and so in PERSUASION, Anne Elliot’s suffering friend Mrs. Smith, whose lodgings at the Westgate Buildings were nearby, would certainly have been a patient of the Hospital.

Three blocks west of the Hospital, we passed the colonnade at Barton Street…

…and found the New Theatre Royal, which has been there since 1805, and is where, in PERSUASION, Jane had Charles Musgrove reserve a big box for his party of nine. The Theatre is still active: a critically acclaimed “Henry IV:Part Two” was being performed there then.

We backtracked on Upper Borough Walk as far as Union Street and made our way south on Stall Street, to the Abbey Churchyard Colonnade…

… which serves as entry to the Abbey Churchyard, the Pump Room, and the Roman Baths, but was called the Pump-Yard in Jane’s time. The west face of the Abbey is directly ahead…

…and we see Bath much as Jane saw it. The Abbey was begun in 1499 and completed in 1615. Only the flying buttresses and the pinnacles are Victorian additions. In the late 1700’s, there were lean-to shops up against the Abbey walls. To the right of the Abbey is a large complex that consists, first, of the Pump Room…

…and farther along, the entry to the Roman Baths.

The remains of these particular Baths weren’t discovered until 100 years after Jane’s death, so visitors in her day took the waters at other locations around the Lower City.

The original Pump Room was built in 1705, but to meet greater demand, was rebuilt in 1795, so on Jane’s first visit in 1797 she encountered a shiny-new building.

Its single, large room was the focal point for Georgian society; a veritable Gossip Central. Upon arrival in Bath, visitors went directly to the Pump Room, and recorded their names and temporary addresses in The Book. At Bath….and people were always AT Bath, and never IN it…..having a fashionable address was all-important. Remember how Catherine Moreland and Isabella Thorpe checked the visitors’ book for Henry Tilney and how impressed they were to find he and his family had taken rooms on Milsom Street.

After fussing over the visitors’ book, people walked around the perimeter of the room, and paused at the Fountain to drink a glass of the natural spring water, which was served at 117 degrees F. and contained 43 different minerals. It doesn’t sound appetizing, but

people swore it helped to cure the gout.

“What a delightful place Bath is, said Mrs. Allen as they sat down near the great clock, after parading the room till they were tired. And how pleasant it would be if we had any acquaintance here.”

After the Pump Room, we proceeded toward the Abbey.

We got there too late in the afternoon to begin a tower-climb, and so left the climbing to the enormous carvings of angels on the Jacob’s Ladders on the West Front.

To the north of the Abbey is this fountain, with a motto that sums the City up: Water is Best.

Bath was also a cook’s paradise, and the fresh meat and produce offered were top-quality. Jane’s household would have done much of its grocery shopping at the lean-to shops around the Abbey. There are still marks where the lean-to roofs joined the walls.

We headed east, toward the River Avon and the Grand Parade.

So where were the Lower Rooms? I’d assumed them to be at the Pump Room, which is in the Lower City, but I was mistaken. Those Lower Rooms which we hadn’t yet found were where, in NORTHANGER ABBEY, a happy event occurred:

“They made their appearance in the Lower Rooms, and here fortune was more favorable to our heroine. The Master of Ceremonies introduced her to a very gentlemanlike young man as a partner—his name was Tilney.”

But the Lower Rooms are gone now.

They were located south of the Abbey, on a beautiful site, near Parade Walk, above the banks of the River Avon. Built in 1708, they were used during the day for promenading, and at night for dancing. Large windows had views over the river and the Parade Gardens, and broad stone terraces surrounded the dance hall. It was the fashion for people to take breakfast at the Lower Rooms after early soaks in the nearby mineral waters. During the 18th century both the Lower and Upper Assembly Rooms were able to attract enough visitors to keep profits healthy for each establishment, but the Lower Rooms were small in comparison to the more modern Upper Rooms, and were situated in a part of town that was eventually declared inconvenient by the most well-to-do residents, who invariably preferred to live higher up the hill, on the Circus or at the Crescent. In 1820, after having fallen into disuse, the Lower Rooms burned to the ground and were not replaced.

The location is at the retaining wall that surrounds the Parade Gardens, on which I stood to take this picture of The Gardens….

View of Parade Gardens, which were open only to subscription holders, as so many city gardens in England still are

…which are alongside the River Avon…

Just north of the Parade Gardens is my favorite view in the City: The Weir at Pulteney Bridge. A Weir is a small overflow type dam that’s used to raise the level of a small river or stream. If you look at your map, you’ll see the channel of the river, to the right of the Weir, where ferry boats bypass the dam.

For a Great Pulteney Street to exist, there first had to be easy access between the Medieval heart of the City and the countryside across the River Avon, to the east, where William Pulteney owned a large tract of land for which he’d made ambitious development plans. But building elegant homes there hinged first upon building a major new bridge to replace the ferry service.

Pulteney chose the highly fashionable architect Robert Adam to design the unusual shop-lined bridge. Inspired by Palladio’s unbuilt design for the Rialto bridge in Venice, controversy surrounded the project. People claimed Pulteney was dragging the modern city back in time by reviving shop-lined bridges, which caused congestion. Nevertheless, the bridge was completed in 1774, with 20 successful shops.

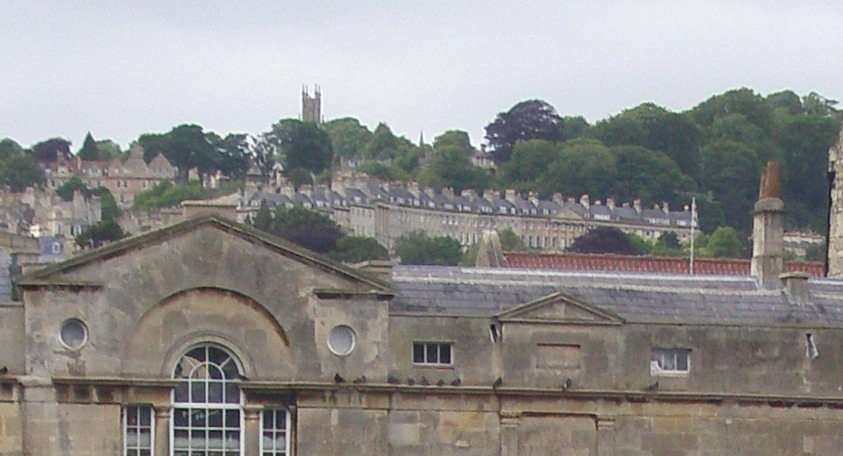

Severe flooding on the River Avon damaged the bridge’s foundations, and it had to be repaired in 1804. From 1801 until 1805, when Jane and her sister lived with their parents at Sydney Place, which was at the far end of Great Pulteney Street, the Bridge was their gateway to Bath. Shops, dances, and most of their friends were on the Western side of the Avon; to do anything, they had to walk over the Bridge.

The Bridge is a good point of reference, if you’re looking for Camden Place, which is high up in the hills. Using the topmost point of the Bridge’s center, look up and to the right.

Just below the tallest church spire, you’ll see the gently curved line of chimney-studded roofs… Camden Place in Austen’s time is now called Camden Crescent.

Jane Austen wasn’t being subtle when she placed PERSUASION’s empty social climber Sir Walter Elliot in Camden Place’s grandest house. Camden Place, which teeters on the edge of Bath’s highest hill, had such insecure foundations that the Crescent was left unfinished; to this day there are an uneven number of houses on each side of the central house.

Once across the bridge, the grand view down Great Pulteney Street becomes visible.

It’s the longest and widest street in Bath at 1100 feet long, and 100 feet wide. The whole structure is supported from below by an enormous system of archways and vaults that provide a level building surface. The fountain in the center of a roundabout at the mouth of the Street marks Laura Place, and in PERSUASION, Austen wrote that “Sir Walter and Elizabeth were assiduously pushing their good fortune in Laura Place,” which was were Lady Dalrymple had rented a house.

By 1800, Great Pulteney Street had become one of Bath’s most fashionable addresses, but for visitors only; all of its houses were rentals.

During Jane’s father’s retirement–from 1801 until 1805–the Austen family lived on Sydney Place, at the end of Great Pulteney Street. This was a high-toned neighborhood for which no excuses had to be made. Each day their daily route from their home to town took them the length of Pulteney Street. Jane Austen walked on this street more than any other in Bath. Jane gave her fictional characters equally vigorous workouts here. NORTHANGER’s Mr. and Mrs. Allen take a house on the street, and PERSUASION’S Lady Russell and Anne Elliot are walking there as Captain Wentworth is sighted:

“…at last, in returning down Pulteney Street, she distinguished him on the right hand pavement at such a distance as to have him in view the greater part of the street. There were many other men about him,

many groups walking the same way, but there was no mistaking him.”

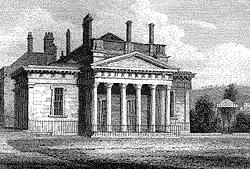

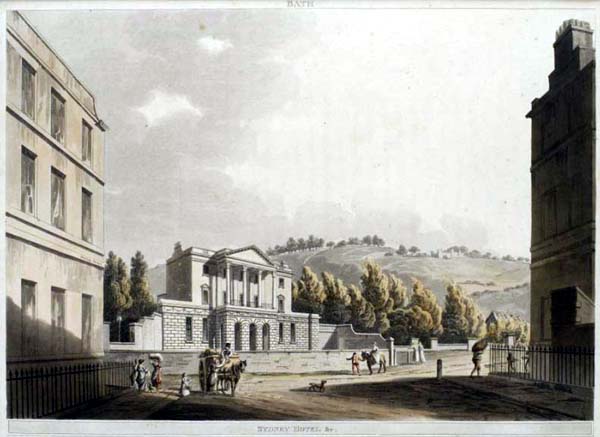

The temple-like building at the end of Pulteney Street, which is now a museum, was in Jane’s time the Sydney House…

…which was open daily for coffee, tea, and card playing, along with drinking, and dancing. And 14 acres of the Sydney Pleasure Gardens and waterways surrounded it.

This made Mr. Austen’s decision to retire to Sydney Place, which was diagonally across the street from Sydney House, very pleasant for him and his wife, although it is written that Jane fainted at the news that they’d be leaving their country home in Steventon for Bath.

Number 4 Sydney Place was the Austen’s main residence in Bath. Returning to the City seemed a natural choice for Mr.Austen’s retirement: it was where he’d married and where there were still many friends and relatives. And although finances were something to be watched, so long as Mr. Austen lived, the brand-new accommodations at Sydney Place were affordable.

The three story building–with a garret–is made of the usual limestone, but has the unusual detail of vermiculated (which also called bird-pecked) rustication and cornerstones. With the park across the street, and hills behind that, Jane’s views would

have been reminders of the countryside she’d hated leaving.

After Mr. Austen died, the ladies of his family were forced to abandon Sydney Place, and spent 6 months on Gay Street. When Gay Street also became too costly, they retreated to Trim Street, which was three blocks from the disreputable Westgate Buildings where Jane placed PERSUASION’s Mrs. Smith.

Although Trim Street is today a pleasant backwater, things in 1806 were totally different, with noxious workshops and alehouses, pimps and prostitutes and beggars. When the ladies of the Austen household were finally rescued from Trim Street, and left Bath for good, they went with “happy feelings of escape.” The social world encapsulated by the Upper Rooms was left behind.

SO, why so much of Bath? Why did this location alone from the real-world serve so extensively as an environment for Austen’s characters?

Emma had a humiliating and instructional picnic on Box Hill. PERSUASION’s characters made a crucial stop at Lyme Regis and the Cobb. Elizabeth Bennett visited one grand estate after another in PRIDE & PREJUDICE. All of Austen’s heroines preferred the life of their prototypical and fictional villages in the countryside. Elinor and Marianne Dashwood took tentative detours into the mysterious metropolis of London: the City where Austen’s villains were most comfortable, and to which her sophisticated characters retreated to repair their jaded lives. But only Bath seems to have become a much-used character unto itself, a place with a personality that played upon the actions of Austen’s invented people.

Here are glimpses of those other actual British locations in Austen’s novels:

At Tate Britain in London, I found this wonderful painting of Box Hill, which gave me an idea of the significance of the Hill, in relation to the surrounding countryside.

And Lyme Regis, where my friends Anne and David go to beach-scavenge for fossils, is still on my list of places to visit.

And grand estates for touring, near to the Austen home in Steventon, were not a dime a dozen, but still quite plentiful; Blenheim Palace at Woodstock is the grandest.

And London? Yes, Jane’s brothers lived there, and she often visited. Her final stay in London was her longest. Her brother Henry had elegant digs at Hans Place, in the Chelsea District.

During my month-long journey in the summer of 2011, I stayed in Sloane Square, in the heart of Chelsea, and just a 10 minute walk south of Hans Place.

I went twice to see where Henry and Jane had lived.

I walked up Sloane Street, to Pont Street, and then to the peace and quiet of Hans Place, which is a circle surrounding yet another of those gated, subscription-only city parks. Hans Place has been largely rebuilt in the Victorian style, but the street and park layouts remain the same.

In 1814, Henry became dangerously ill and Jane was summoned from Chawton Cottage to nurse him through his fevers and his long convalescence. Henry’s long recovery period was probably due to the very treatments his doctor prescribed: calomel (which was a powdery mix of mercury and chlorine), and then huge volumes of blood-letting. Henry lived in the corner building, at #23. Then, as now, the house had a park view:

This is the view that Austen would have had from the windows of Henry’s house (minus the pavement and cars)

A single building in the Georgian Style remains, at # 30 Hans Place. Henry’s home would have looked very much like this:

But London is unimaginably large. And Hans Place…

…is in the small West London neighborhood of Chelsea…

….which is but a tiny part of Greater London:

So, during her visits to London–which even then was an epically huge sprawl– Austen would never have had time or experience enough for learning and truly understanding the City…not that anyone could do so, then or now. Her purpose when traveling to London was to be useful; as a nurse, or as an Aunt. Tourism was never the main objective. Her sheltered and limited exposures to London could not have equipped her for the task of writing intimately about such a multi-cultural City.

I’d read histories of Bath, but didn’t want to know what literary critics thought Austen’s motivations were for her extensive use of Bath in her fiction, as compared to her sketchy use of London. Instead, I wanted to speculate about her reasons based upon my own visits to the actual places. I especially wanted to see how Bath, which affected Austen’s imagination so powerfully, would work upon my own imagination.

Austen’s specificity about Bath provides a striking contrast to her descriptive-norm, in which conversation and action happen in generic villages or in the misty world of country fields. In the Bath stories, streets are named and Rooms are conscientiously identified. Readers in Austen’s time, many of whom would also have been to Bath, did not have to imagine where Catherine and Henry and Anne and Frederick walked, or what each street or address signified. For Austen’s country settings readers could imagine their own particular patches of green, but in Bath, everybody was on the same page, literally and figuratively.

Bath was the only city in England where Austen lived for a meaningful stretch of time. We know she much preferred country life, as did her heroine Anne Elliot, but nothing makes green meadows sweeter than a longing for them, and so Austen banished Anne to Bath, as she herself had once been. Art is achieved by the juxtaposition of carefully chosen contrasts: of shadow and light; of desires thwarted or gained. Bath was the cityscape that Austen needed to counterbalance her country-scape, and Bath performed the double-duty of providing not only a physical environment for her stories, but one whose meaning was widely understood.

I came to these conclusions. Bath was a homogeneous-looking City; and was thus a useful symbol for the constraints of the social order of Austen’s time and of her particular world. Its contained spaces provided a manageable urban universe for Austen’s characters. The physical layout of Bath is comprehensible. The wholesale rebuilding which resulted in the City that Jane knew, and which we still enjoy today, is mortar-and-stone evidence of massive social and monetary aspiration. It is also inherently dramatic. Crescents look like theatre backdrops. Its thousand-foot-long street is a parade ground over which all its visitors must of necessity pass. Its Rooms function as mazes: the deeper one goes into the Rooms, the deeper one delves into society’s workings, or into the hearts of Austen’s characters. Bath has become to me as much a character as Catherine Moreland, or Anne Elliot, or Captain Wentworth. It has a particular and omnisexual shape: whether nicely rounded or reassuringly straight, it is always tastefully solid, and never gargantuan. It has a temperament: with mercurial weather that can be calm and kind, and wet and cold. And its golden limestone even gives it a complexion, which changes with the light. We return again and again to Austen’s books because we love her characters. I think Jane’s imagination returned again and again to Bath because of the very human qualities which the City personified.

Today’s Crowd at the Abbey Churchyard Colonnade is not quite as tastefully attired as Jane’s Regency-era acquaintances were.

Copyright 2012/2013 Nan Quick–Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without

express and written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

11 Responses to Jane Austen & Bath, England