Replica of the Salem East Indiaman FRIENDSHIP, at the Salem Maritime National Historic Site, on the North Shore of Massachusetts

JANUARY 2013. MARITIME NATIONAL HISTORIC SITE; NEIGHBORING MARBLEHEAD; NATHANIEL HAWTHORNE’S HOUSE OF 7 GABLES; FEDERAL-ARCHITECTURE-HEAVEN ON CHESTNUT STREET.

If I had my druthers, I’d be taking pictures and writing in Italy and England for half of every year. But practicality and logistics make that impossible, so I’m finding places to write about that are a bit closer to home. I’m defining home as the entire Eastern Seaboard, and have thus scheduled trips over the next several months to Charleston, South Carolina and to Palm Beach, Florida; to Washington, DC at cherry blossom time; to Boothbay Harbor and to Camden, Maine; to Stockbridge, Massachusetts and to Millbrook, New York and to the Hudson River Valley. But before those moderately-distant gallivants, I thought to revisit Salem, Massachusetts, which, at a two hour drive from my New Hampshire home, is close enough to qualify as back-yard treasure.

Salem in wintertime, when its streets echo and its multitudes of sketchy psychic reading and magic shops are shuttered, is truer to its essence: a bit melancholy—-as a seaside port whose greatness is centuries past must be–but still blessed with exquisite neighborhoods of historic architecture and inspiring stretches of waterfront parks.

My goal when traveling is to discover the Personality of Place, in its roundest and most complete form. Exploring in seasons of less than clement weather is rewarding because inclemency clears spaces and ensures privacy; cloudy skies and empty byways set my mind to imagining how other people in other times might have beaten the same paths as those I choose to follow. Over the course of three very cold and overcast January days, it seemed I had Salem entirely to myself. Absent the crowds of tourists who squeeze themselves up the hidden chimney stairway at the House of Seven Gables during summertime, or the mobs of wanna-be witches who parade over its streets at Halloween, Salem became a timeless place, a place whose buildings seemed to be holding breath as they awaited their former occupants, whose presence might resuscitate their rooms.

SO, why visit this small, semi-haunted city that clings to the rocky coast of Massachusetts’ North Shore? Salem’s fame rests upon a quartet of attributes:

*As one of the world’s great trading ports. By the end of the 18th century, Salem had achieved maritime glory. Traces of that glory remain at the Maritime National Historic Site on Derby Wharf, where the National Park Service offers guided and self-guided tours.

*As the birthplace of Nathaniel Hawthorne. The author, who immortalized one of Salem’s most famous homes in THE HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES, continues to intrigue us 150 years after his death, in part because his unearthly handsomeness matched his unearthly fiction (per family legend, a gypsy woman, struck by the young Nathaniel’s beauty, asked: “Are you a man or an angel?”).

Painting of Nathaniel Hawthorne in his prime, by Charles Osgood. Courtesy of the Peabody Essex Museum

*As a nearly-unique catalog of 200 years of American domestic architecture. Salem still has a wealth of buildings from the First Period (1626-1725); the Georgian Colonial Era (1720-1780); and the glorious Federal Era (1780-1830). Chestnut Street is the nexus of the McIntire Historic District.

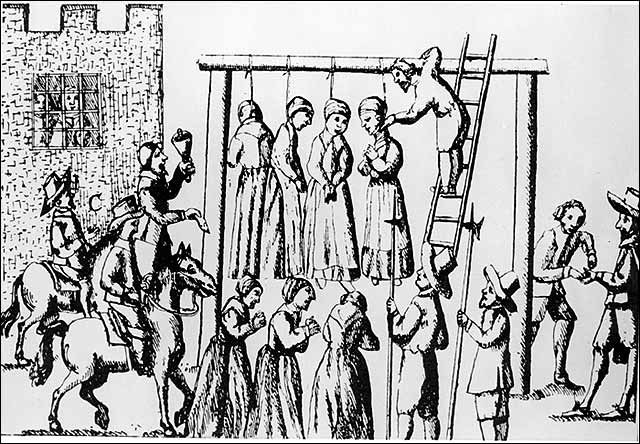

*As the site of the shameful 1692 Witchcraft Trials. During a grim time of mass hysteria, intolerance and delusional thinking, 20 innocent women were condemned to death: 19 by hanging, and 1 by torture. Nathaniel Hawthorne’s ancestor, John Hathorne (Nathaniel added the “W” to his surname) was one of the judges responsible for those sentences.

And for a fifth attribute—-one of Salem’s crown jewels –I’ll devote my next article entirely to the treasures at the PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM, where the architecture is sensitive and surprising, and the ever-evolving collections are tightly curated and imaginatively displayed.

During the first hours of my re-visit to Salem (I’d been there before, but not while grasping my Armchair Traveler’s pen and paper and camera), I headed to the Maritime National Historic Site where Nathaniel Hawthorne left yet another deeply impressed set of his finger prints, one that all American schoolchildren of a certain vintage encountered when they were assigned THE CUSTOM-HOUSE, an autobiographical meditation which Hawthorne used to introduce THE SCARLET LETTER, the novel that made him world-famous. As he composed THE CUSTOM-HOUSE, Hawthorne had recently been fired from his day-job as surveyor of the port (where he’d worked from 1846 to 1849), but already regarded his tenure at the Custom-House as little more than a bad dream which had made it impossible for him to pursue his true, writer’s calling.

The Custom House was the principal building in the complex of wharves and warehouses along Derby Street, and was where import duties used to fund the federal government were collected. Constructed in 1819, and with an octagonal cupola added in 1854, the building is a prime example of the American Federal style.

The Custom House, on Derby Street, across from the Derby Wharf area of the Maritime National Historic Site

Nathaniel Hawthorne’s office at The Custom House was on the 2nd floor, directly over the front entry

Salem began humbly. In 1626, the waters of the Harbor and the nearby Atlantic Ocean were rich with codfish. Once the small population of the fishing village first named Naumkeag (“the Fishing Place” to the Original Americans) had been more than amply fed, the energetic inhabitants began to build wharves where excess cod could be salted and dried and transformed into the fish- flakes that were highly sought by the rest of the world. In 1628, a new British governor renamed the village Salem (for “Place of Peace”), and by the mid 1630s, the quiet fishing village had been transformed into one of the busiest and most prosperous ports on the East Coast. But no matter whether the dwellings of Salem’s residents were elegant or rudimentary, every speck of air in every home was permeated by the unavoidable smell of the fish-flakes that were making Salem’s fortune! Salem’s merchants soon added lumber from the virgin forests of Massachusetts to their export cargoes, and proceeded to build a lucrative trade with West Indies merchants, who sent their own molasses, sugar, cotton, salt, tobacco, and, regrettably, also a few slaves, back to the cold shores of Massachusetts. By the early 1700s, trade expanded to Canada’s maritime provinces, the Netherlands, Bermuda, the British Isles, the Madeira Islands, Canary Islands and the Azores.

Benjamin Hawkes House, adjacent to

The Custom House. Construction was begun in 1780, but suspended until

boat builder Hawkes acquired it in 1801, and then renovated and completed the structure. The brick house behind the Hawkes House is Derby House, the

oldest surviving brick house in Salem, erected in 1762

In 1785, the GRAND TURK was the first Salem vessel to set sail to Canton, where it arrived in late 1786. K. David Goss’s invaluable essay THE MARITIME HISTORY OF SALEM, tells us that its cargo included “tobacco, pitch, tar, rice, flour, butter, wine, iron, sugar, fish, oil, chocolate, prunes, ginseng, beef, brandy, rum, bacon, hams, cheese, candles, earthenware, and beer,” which were exchanged for “teas, boxes, ox hides, chamois skins, muslin and paper.” Subsequent Salem voyagers returned home with the famous blue and white Canton China that still graces many of the homes in Salem, along with precious bolts of embroidered silk. With this Far East landing, the great years of New England’s trade with China began. But surpassing even the China trade was the Sumatran pepper trade, which helped Salem’s most ambitious (and lucky) merchants to amass incredible fortunes.

Replica of the FRIENDSHIP, which

was launched in 1797, and made 15 voyages: to Batavia, India, China, South America, the Caribbean, England, Germany, the Mediterranean and Russia

By the early 1800s, many of the ships that had docked in Salem began to be rerouted to the now-better-equipped Port of Boston, and the long, slow death of Salem’s port that Hawthorne bemoaned in his CUSTOM HOUSE essay had begun. When one imagines the hive of activity that had buzzed on these wharves—the forests of ship masts that had jostled for position; the warrens of warehouses which had blanketed a waterfront which is today barren and wind-scoured—one is heavily reminded of transitory nature of all Golden Ages. My mention of being scoured by icy winds isn’t poetic: by the time I’d walked the length of Derby Wharf, my Serious Winter Clothing had begun to seem Merely Lightweight, and, with chattering teeth, I headed inland, thinking about making plans for my next trip to Salem, when I’d stay overnight at the venerable Hawthorne Hotel (I know…everything in town does seem to be named after this gentleman). But despite the cold, my solitary stroll out into the Harbor had given me a snout-full of bracing air (which these days smells nothing like fish-flakes!), much food for thought, and enormous pleasure.

Two weeks after my freezing walk along Derby Wharf, I was back in Salem, and on a day when a snowstorm was barreling in from the West. But since I had many hours to pass before checking into the Hawthorne Hotel, I drove several miles further out toward the Ocean, to the village of Marblehead.

QUIET doesn’t begin to describe what Marblehead is like, on a Monday, in late January! If you’re planning to visit that village, I recommend that you wait until the summer months, when the historic buildings are open, and shops keep regular hours.

Marblehead is generally recognized as the birthplace of the American Navy. During the American Revolution, the schooner HANNAH, owned and crewed by Marblehead residents, was the first vessel commissioned for the Navy. In Abbot Hall (the town hall and historical museum), the original of Archibald MacNeal Willard’s much-reproduced painting SPIRIT OF ’76 can be seen. And from June through October, the Jeremiah Lee Mansion is open for tours. The house was built in 1768 for the wealthiest merchant and ship owner in Massachusetts, and is most noted for its rare 18th century English hand-painted wallpapers, and its outstanding collection of early American furniture. Despite my disappointment at not being able to find a single open café (I was desperately in need of a mug of hot chocolate), my little amble through the town did yield many pretty vistas, which I include here.

THE SPIRIT OF ’76, Presented by General John Devereux on April 27th, 1880. “In memory of the brave men of Marblehead who have died in battle on sea and land, for their Country”

Summertime view of Marblehead Village, with Marblehead Harbor, and then Marblehead Neck in background

Returning to Salem from Marblehead, I made a spontaneous decision: I’d stop at the House of the 7 Gables, a place I’d last toured when I was about 8 years old. With a snowstorm percolating, most sensible people were already hunkered down at home. But the House was still open for business and so I plunked down my cash for a group tour that ended up being a very rewarding private visit, since I was the only civilian onsite that afternoon.

The property’s website nicely summarizes a long history:

“The House of the Seven Gables was built by a Salem sea captain and merchant named John Turner in 1668 and occupied by three generations of the Turner family before being sold to Captain Samuel Ingersoll in 1782. An active captain during the Great Age of Sail, Ingersoll died at sea, leaving the property to his daughter Susanna, a cousin of the famed author Nathaniel Hawthorne.”

(Readers: get used to it! Visit Salem, and you’re in Hawthorne-Land.)

“Hawthorne’s visits to his cousin’s home are credited with inspiring the setting and title of his 1851 novel THE HOUSE OF THE SEVEN GABLES.

Hawthorne began his novel this way: “Half-way down a by-street of one of our New England towns stands a rusty wooden house, with seven acutely peaked gables, facing towards various points of the compass, and a huge clustered chimney in the midst…”

“Caroline Emmerton, a philanthropist and preservationist, founded the present day museum to assist immigrant families who were settling in Salem. Inspired by Jane Addam’s Hull House, she purchased what was the old Turner Mansion in 1908 and worked with architect Joseph Everett Chandler to restore it to its original seven gables”

(Two gables had been mislaid somewhere along the way.)

“Chandler was a central figure in the early 20th century historic preservation movement and his philosophy influenced the way the house was preserved. Emmerton’s goal was to preserve the house for future generations, to provide

educational opportunities for visitors, and to use the proceeds from the tours to fund her settlement programs.”

“Over time Emmerton and the organization’s trustees acquired and moved to the site five additional 17th, 18th and 19th century structures: The Retire Becket House (1655); The Hooper Hathaway House (1682); Nathaniel Hawthorne’s Birthplace (c1750); The Phippen House (c1782); and The Counting House (c1830). Today, The House of the Seven Gables campus constitutes its own national historic district on The National Register of Historic Places.”

The House of the 7 Gables has become one of the most-visited historic properties in America, so my being able to experience it without the usual crowds was a happy event.

Unfortunately, interior photography during normal house tours is prohibited, but I’ve been able to find photos online which were taken by visitors who had special permission to take pictures. The lure of a “secret stairway,” which is the only thing I remembered from my childhood visit, remains, but the purpose of those stairs, which wind up and around a chimney, and are hidden behind a panel in the Dining Room, is unknown. I speculate that they provided an escape for a host who’d become weary of his guests. As the hostess gamely oversaw the serving of yet another dinner-course, and all heads at the table were turned toward the groaning tray of food being borne in from the kitchen, the host sidled to the innocuous-looking panel, tapped it, slipped into the passageway that revealed itself…and crept up into the drafty quiet of his attic.

The Dining Room’s Escape Hatch, hidden behind a verdigris-painted panel, which was installed in 1692 by John Turner, Jr. (who we can presume was the restless host of my fantasy). Photo courtesy of The Distracted Wanderer/Linda Orlomoski

The elegant Dining Room, with Chinese Wallpaper to lust after. Photo courtesy of The Distracted Wanderer/Linda Orlomoski

Living Room, or Main Hall, with window facing Salem Harbor. As the wealth of the occupants increased, the principal rooms in the House were redecorated. The decor in the Main Hall dates from 1725, when John Turner Jr. added Georgian-style paneling and double-sash windows. Photo courtesy of The Distracted Wanderer/Linda Orlomoski

Vivid, spectacular hand-blocked wallpaper in the Main Hall, with portrait of Hawthorne’s cousin Susanna Ingersoll–who he called “The Duchess.” At the time of her death, Susanna was the second most wealthy woman in Salem. Hawthorne particularly loved her gossip; many of the tales she told about the misdeeds of departed Salem-ites were woven into his fiction.

Photo Courtesy of The Distracted Wandered/Linda Orlomoski

Directly over the Main Hall is the Master Bedroom, or Parlor Chamber, with a bed for Serious Dreaming. Photo courtesy of The Distracted Wanderer/Linda Orlomoski

After our ramble through the House of the 7 Gables, my guide led me to another house on the property, the birthplace of Nathaniel Hawthorne, which is now set up like a museum, filled with Hawthorne family memorabilia.

Nathaniel Hawthorne was born in this house on 4 July 1804, when it was situated at 27 Union Street. The modest gambrel-roof structure was moved to its present site in 1958.

Hawthorne’s birthplace, with landscaping designed by Dan Foley. The elm tree is extremely old and part of the original canopy.

Even during the bleak winter months, the two Seaside Gardens that surround the buildings in the House of the 7 Gables Historic District

are soothing and pretty. The larger of the two gardens is managed by Robyn Kanter of Kanter Design Associates. The raised bed areas of the garden are considered to be the most historically significant feature of the grounds. The patterned beds were laid out by Joseph Chandler, a landscape architect hired by Caroline Emmerton in 1909.

The Main Garden. Honeysuckle dominates the shrub border. Viburnums, lilacs, yews and (OF COURSE) a Hawthorne tree round out the plantings.

SO, before we take our leave of all-things-Nathaniel (but not completely, because I had still to check into my room at the Hawthorne Hotel), the question remains: what causes our enduring fascination with Hawthorne? He was by all accounts an introverted and rather peculiar man…but one whose long-delayed successes—artistic, matrimonial, and financial—can also give hope to other late-bloomers of the World. Hawthorne’s life was a thicket of seemingly UN-integratable aspects which included:

*His gnarly Salem-family history, which made him feel eternally obliged to atone for the sins of his witch-condemning forebears.

*His childhood as a beloved and cosseted and rather peevish boy, who was largely surrounded by doting women.

*His years at Bowdoin College, where his classmates included Franklin Pierce, Horatio Bridge, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow.

*His ten post-college years, during which he hid in his bedroom at his mother’s house, while he penned macabre tales.

*His years working at the rough-n-tumble Ports of Boston, and Salem, where–no sissy–he prospered.

*His 6 months with the Utopian Movement, at Brook Farm, where he quickly tired of shoveling manure, and griped about Margaret Fuller’s

“Transcendental Cow.”

*His significant but second-tier literary talent. I know…people will argue about this. But apart from his mountains of letters (which reveal a much less prissy voice than the voice which permeates his novels), and his volumes of wonderfully odd short stories (which, to this day, can be surprisingly twisted, and almost modern), Hawthorne’s novels, apart from THE SCARLET LETTER, haven’t worn well.

*His flirtation with the formidable Elizabeth Peabody, followed by his epic and erotically-charged love match with Elizabeth’s sister, the very patient Sophia Peabody, with whom he eventually had three children. Sophia, youngest of the three famous Peabody sisters of Salem, suffered from headaches until the day she was married. But a ring on her finger, and then Nathaniel in her bed, immediately cured her lifelong ailments.

During her seemingly interminable 5-year-long engagement to Nathaniel, who was in many respects a VERY slow starter, Sophia painted this scene for her beloved, to show him how idyllic their married life would eventually be! The two tiny figures in this idealized Italian landscape, titled “Isola San Giovanni” represent Sophia and Nathaniel.

*His years in Concord, Massachusetts, during which he was part of the quartet of luminaries that also included Ralph Waldo Emerson, Henry David Thoreau, and Bronson Alcott.

*His deep friendship with Herman Melville, who dedicated MOBY DICK to him.

*His many public servant jobs (the zenith being his appointment as U.S. Consul to Liverpool by his old friend, President Franklin Pierce).

*His sojourns in Italy, where he lived in Florence, and in Rome.

It is precisely because of Hawthorne’s multitude and confusion of personal qualities and circumstances that we continue to be perplexed by him…despite the best efforts of his industrious biographers. Who indeed was this day-dreamer, this introverted gadabout who during his 60 years seemed to be everywhere that counted, and to know everyone who mattered? Enigmas such as Hawthorne don’t come along every day.

PHEW! After all my Riddle-of-Hawthorne-Pondering, a little nap seemed like a good idea, and so, as light snow began to fall, I finally hauled myself to the Hawthorne Hotel, which overlooks Salem Common.

Statue of Nathaniel Hawthorne, by Bela Lyon Pratt. Located on–of course–Hawthorne Blvd., with the Hawthorne Hotel in the background.

My pre-snowstorm view of the Andrew-Safford House, & the Federal Garden. Both properties are owned by the Peabody Essex Museum.

But before day’s light failed I still needed to walk along Chestnut Street, where I’d inspect the architectural treasures of the McIntire Historic District. I piled on every piece of warm clothing I’d packed, and headed back out onto the slippery sidewalks, worried that my fingers might get so cold that I would not be able to click my camera.

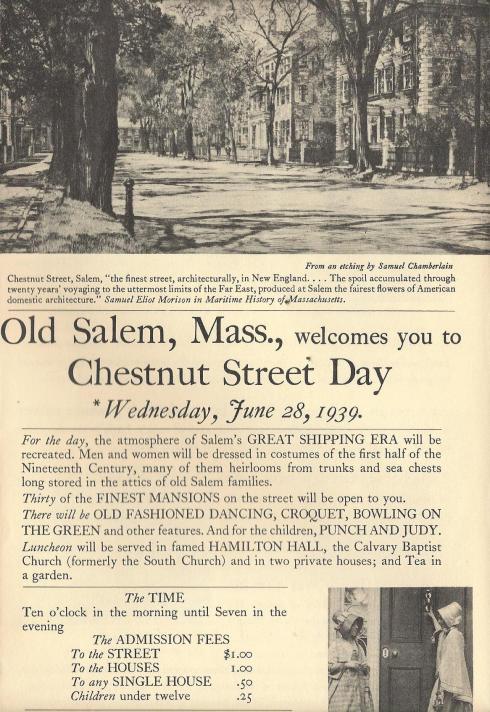

Bryant F.Tolles, Jr. begins the chapter about Chestnut Street in his definitive ARCHITECTURE IN SALEM this way:

“Most who have commented in print about Chestnut Street, whether they are serious scholars or more casual writers, consider it to be one of the most outstanding streets architecturally in the United States. Surely, as a collection of Adamesque Federal buildings (all but one residential and dating from 1800 to c. 1830) it has no equal anywhere in the country. A physical monument to Salem’s most prosperous years as a world leader in maritime trade, Chestnut Street has been a peaceful and beautiful home to merchants, sea captains, diplomats, statesmen, politicians, artists, and literary men, who have all contributed to the city’s rich historic legacy. Chestnut Street was first laid out in 1796 by the town of Salem and is a superb example of urban planning. Initially it was forty feet wide, but in 1804, at the urging of John Pickering and Pickering Dodge, it was doubled in width.“

Chestnut Street is the center of the neighborhood that’s been designated The McIntire Historic District, so-named in honor of the designer, master builder and carver Samuel McIntire (1757—1811), whose refined interpretations of the English Adamesque style influenced the work of a generation of talented craftsmen. Grand structures built by McIntire and his contemporaries (most notably: William Lummus, John Nichols, Perley Putnam, William Roberts, Jabez Smith, Sims Brothers and David Lord) adorn the length of Chestnut Street,

and the photos which follow illustrate my favorites.

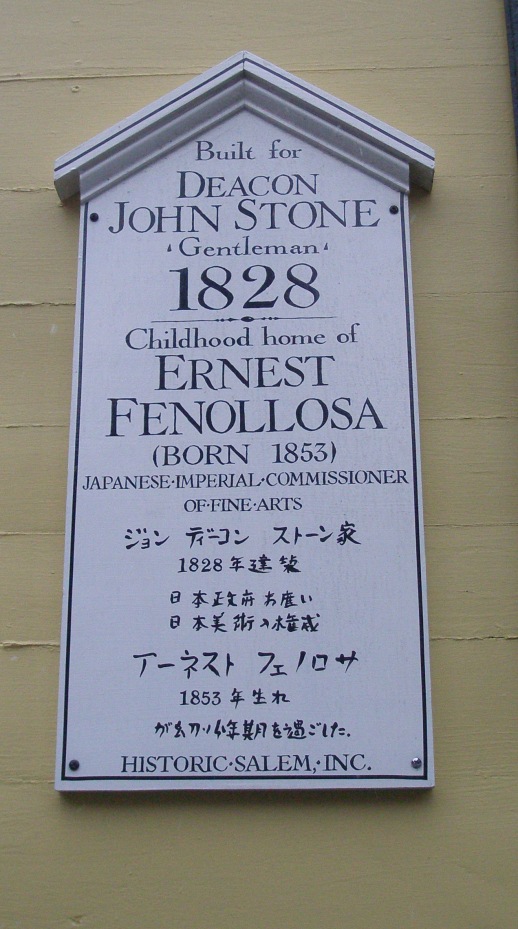

The low-numbered-end of Chestnut Street, as seen on the cold and stormy afternoon of January 28, 2013. The Deacon John Stone House is the yellow double structure. Hamilton Hall is the adjacent brick building.

Hamilton Hall, at #9 Chestnut Street. This was designed by Samuel McIntire as a social facility for the city’s Federalist merchant families. Constructed from 1805–1807.

Park adjacent to the Gregg-Stone House. This green space once accommodated McIntire’s

masterpiece, the South Church (built in 1804, but destroyed by fire in 1903).

Lee-Benson House. #14 Chestnut Street. Built in 1835, this is one of the earliest examples of the Greek Revival style in Salem.

Ichabod Tucker House. #28 Chestnut Street. Believed to be the 2nd oldest dwelling on the Street, it was built by Sims Brothers in 1800. In 1846 the facade was completely rebuilt; today we have no idea what the Sims Brothers facade looked like.

Allen-Osgood-Huntington Triple House. #s 31-33-35 Chestnut Street. Built in 1829, this is the tallest of the Street’s Federal-era buildings.

Phillips House Museum. #34 Chestnut Street. This is the only house on the Street which was moved there from another location. The ornate Federal-era wooden structure was built in the early 19th century on land in South Danvers (now Peabody). It was moved to its current location in 1824.

Finally accepting that the weather was getting the better of me, I slid back to the comforts of the Hawthorne Hotel, where I warmed myself, and afterwards visited the Hotel dining room, where I savored a dinner of warm spinach salad with asiago, pomegranate and hazelnuts; followed by sautéed shrimp and seared scallops, served with grilled asparagus and herbed risotto….an elegant assemblage of tastes.

Readers of my previous travel diaries will have learned that I’m a sucker for night-views from my various hotel rooms, and the vistas from my 5th floor perch out over snowy Salem that evening didn’t disappoint.

When I woke on the morning of January 29th, and peered out of my windows, this snowy scene of the Peabody Essex Museum’s magnificent Andrew-Safford House (about which I’ll say more in my next article) and Federal Garden greeted me.

After breakfast, I hustled over to the Peabody Essex Museum to attend a Press Preview Opening Reception, which would introduce their

pivotal show of modern Indian art: MIDNIGHT TO THE BOOM—PAINTING IN INDIA AFTER INDEPENDENCE (from the Museum’s Herwitz Collection…

on view from February 2nd through April 21, 2013).

Sane travel-writers do not attempt to give comprehensive reports about the contents of museums. Large repositories of treasure cannot be described without venturing into the realms of tiresome and academic cataloging. But for small, precisely-focused collections such as those displayed by the Peabody Essex Museum, an almost-itemized approach is quite possible, and appropriate.

In my next article, I’ll report extensively on their revelatory Show of modern Indian art, and will also include glimpses of some of the other galleries at the Museum.

Copyright 2013. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers.Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

0 Responses to The Steel-Gray Charms of Salem in Wintertime