This is how the Garden-Sausage is made. The Blue Steps, at Naumkeag, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The Steps, built in 1938, are being restored, and the birch trees surrounding the Steps have all been replaced. Other areas at Naumkeag are also undergoing long-needed restorations.

October 2013. As I approach the 12-month-mark of publishing my Diaries for Armchair Travelers, I marvel that the things which obsess me have been at least of passing interest to readers in 83 countries. Blogging (and I must declare that I continue to abhor the word “blog,” which is clunky and inelegant) is as optimistic and impractical an activity as shoving scrawled messages into bottles, and then lobbing the fragile containers into the sea. But web-trawlers keep finding my little missives, and so I keep dispatching more, toward parts unknown. Now that my traveling and picture-taking and writing occupy most of my time, people ask: “Why and how did you begin?” ….funny how unintentional, sideways sliding can ease us into some of our happiest endeavors.

In the fall of 2008 David Patrick Columbia, the editor of NEW YORK SOCIAL DIARY, invited me to begin writing about the international wanderings that were a byproduct of the promotional work I did for my garden furniture design business. Over the next four years, as David published my occasional travel diaries, I found that exploring and photographing and researching suited me well. With each article, my author’s footing became more secure. And as I progressed, my articles stretched their legs and lengthened their stride and finally burst through some seams: no longer could they fit within the tightly-tailored fabric that NYSD’s daily web pages required (And no….NYSD isn’t for the vapidly social. If you savor Anthony Trollope, you’ll enjoy David Patrick Columbia’s musings.). With David’s encouragement, my longer-format Diaries for Armchair Travelers commenced, and being able to allow each of my topics to be revealed unhurriedly, as I amble along ever-more-circuitous paths, has become one of my greatest pleasures.

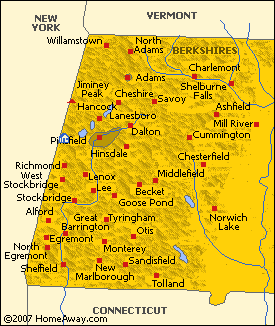

I’ve recently returned from a month in England, which will eventually yield ten new Diaries. But since I usually write chronologically, I have some catching-up to do, and so now take you along with me on my early-June jaunt to the Berkshire hills of Massachusetts: to visit Naumkeag, one of the world’s most quietly idiosyncratic masterpieces of garden design; and then to The Mount, the home that Edith Wharton built.

Many of us who are fortunate enough to own a tract of land hanker for a proper garden. There are those for whom hiring a designer would be unthinkable (that would be me…not because I’m enormously talented, but because I LIKE shoveling dirt and piling rocks and growing plants), and then there are others who prefer to engage a partner to guide them as they plan their little Edens. Whichever our gardening-approach, most garden-makers think in terms of creating “rooms” outside; discrete but connected spaces through which to stroll. I have succumbed to that room-making impulse, again and again, but only in modest fashion:

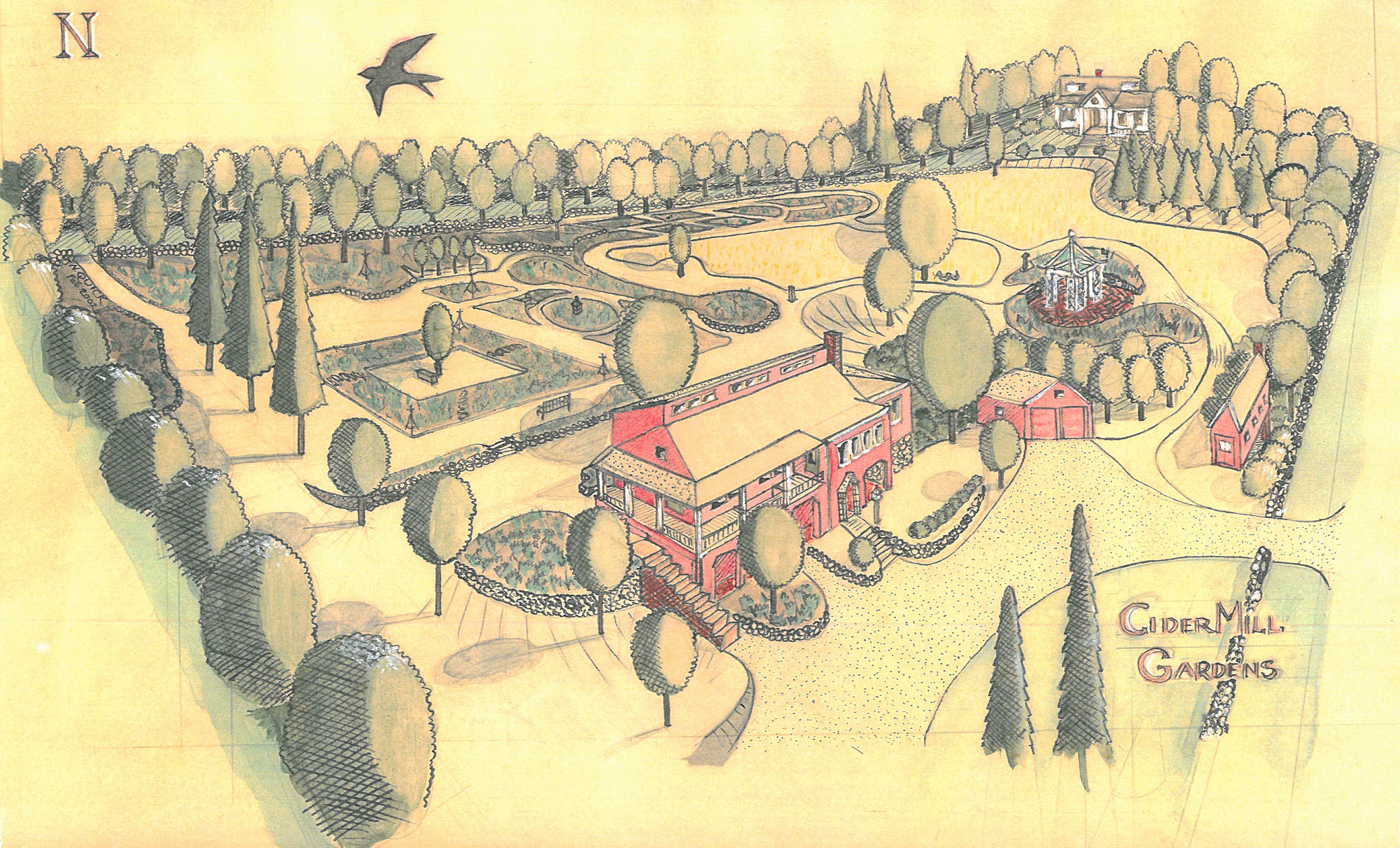

The gardens I made at my

previous home in New Hampshire. Pen, ink & watercolor sketch done by Nan, in Feb. 2002

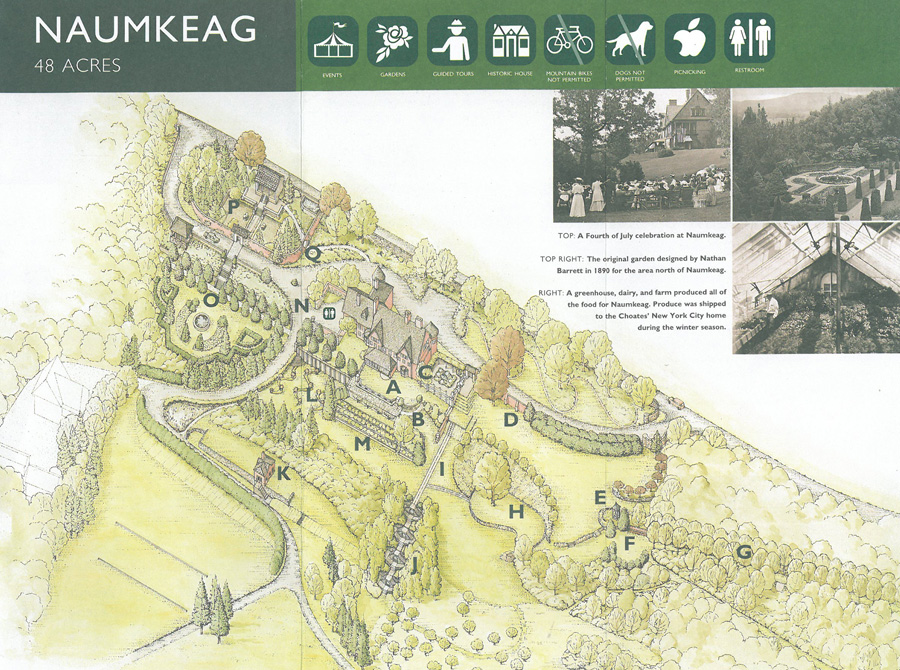

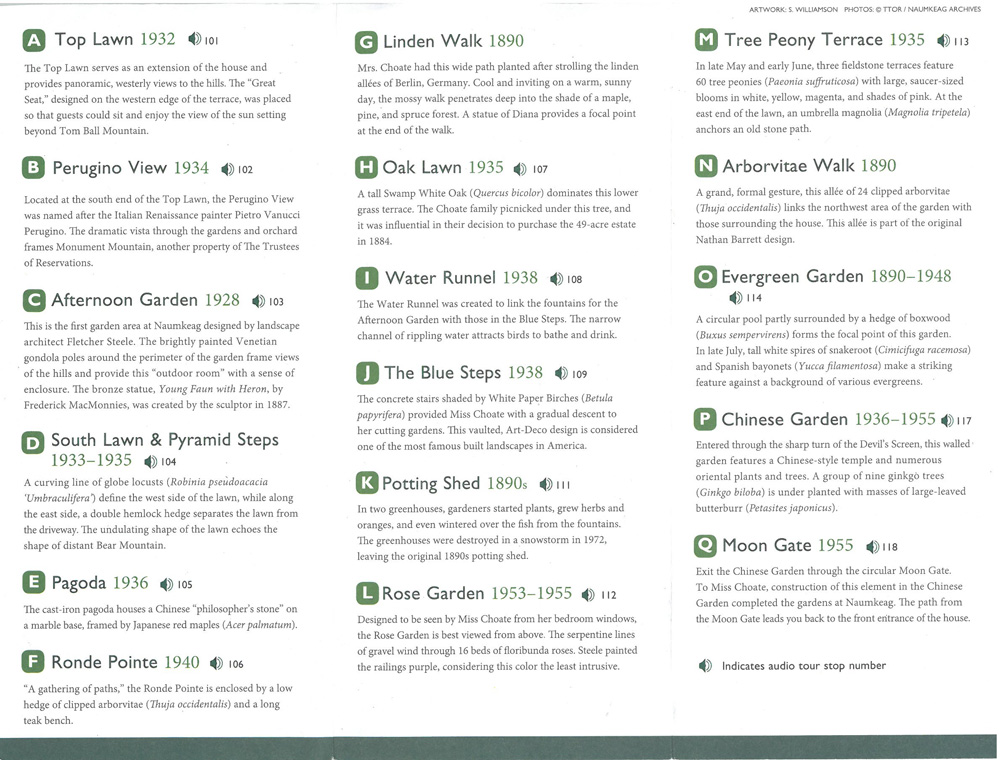

In 1929, Mabel Choate inherited a rambling, shingle-style house on 48 acres that hugged a west-facing slope in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

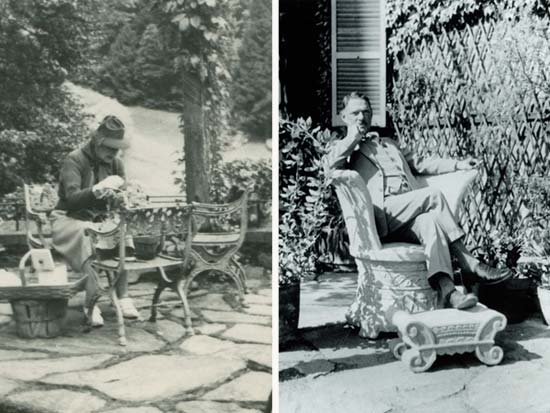

Mabel Choate and her pooch on the newly-planted Arborvitae Walk. Image courtesy of FLETCHER STEELE, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, by Robin Karson.

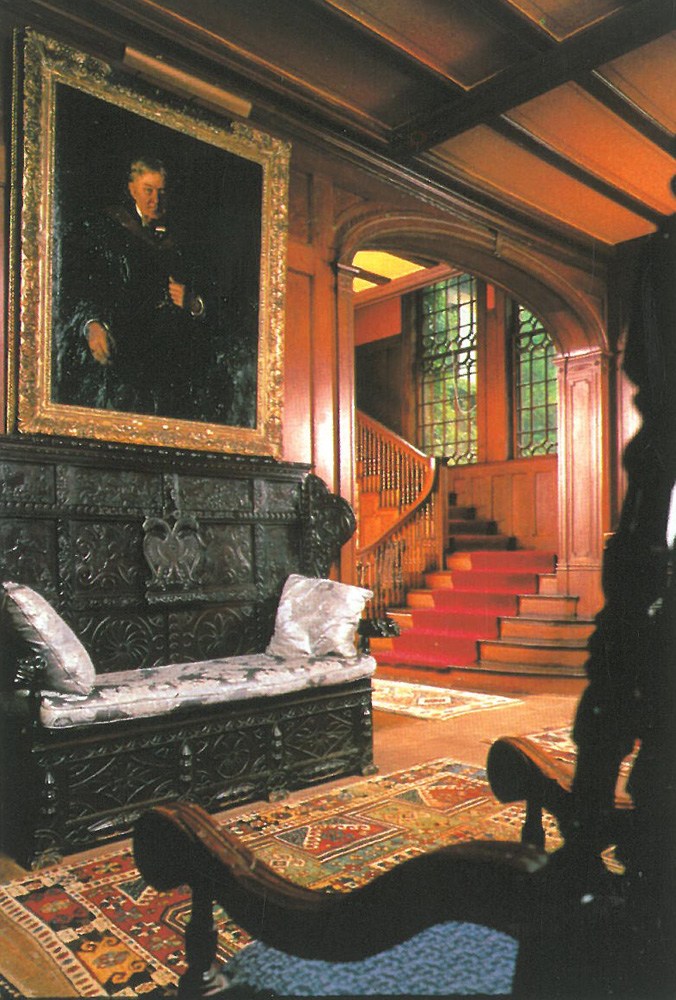

The house, designed by the architect Stanford White, had been her family’s summer residence, and was one of many grand homes constructed on the Berkshire hills during the late 1800s, when a summertime influx of wealthy New Yorkers caused the area to be called “the inland Newport.”

East-facing Service Court entry to Naumkeag, with the tail-end of my trusty Toyota Highlander (note my little Mona Lisa bumper sticker).

Even before she came into possession of the property her father had called “Naumkeag” (which referenced the original, Native American name of Salem, Massachusetts, his hometown), Mabel, by then a woman in her 50s, had her own ideas about how the quite presentable formal gardens, developed in 1890 by the designer Nathan Barrett, might be refined and expanded.

An arborvitae allee and two terraces at the north end of the property existed, but Mabel, who’d traveled the world and had thus learned the difference between the merely good and the truly great when it came to garden design, was on the lookout for someone to help her better link her home to the beautiful landscape surrounding it.

In 1926, while attending a lecture at the Lenox Garden Club, Mabel found that Someone.

The next afternoon, Mabel invited the speaker to tour her gardens, with the aim of creating an “outdoor room” where she might sun herself. As they discussed her modest goal, little did she or Fletcher Steele suspect they’d just begun what would become a close friendship, and an obsessive, sometimes exasperating and always-costly 30-year-long project of garden transformation. As Steele perused the Choate set-up, he declared “I couldn’t possibly work for anyone whose back door looks like that!” Unoffended by his candor, Mabel decided that her back door was indeed “dreadful,” and thus approved Steele’s proposal for a new wall and service court which would create a sheltered area just outside her library, at the south end of her house.

View from the the Service Court through the Gate, and down toward the Water Runnel and the Blue Steps

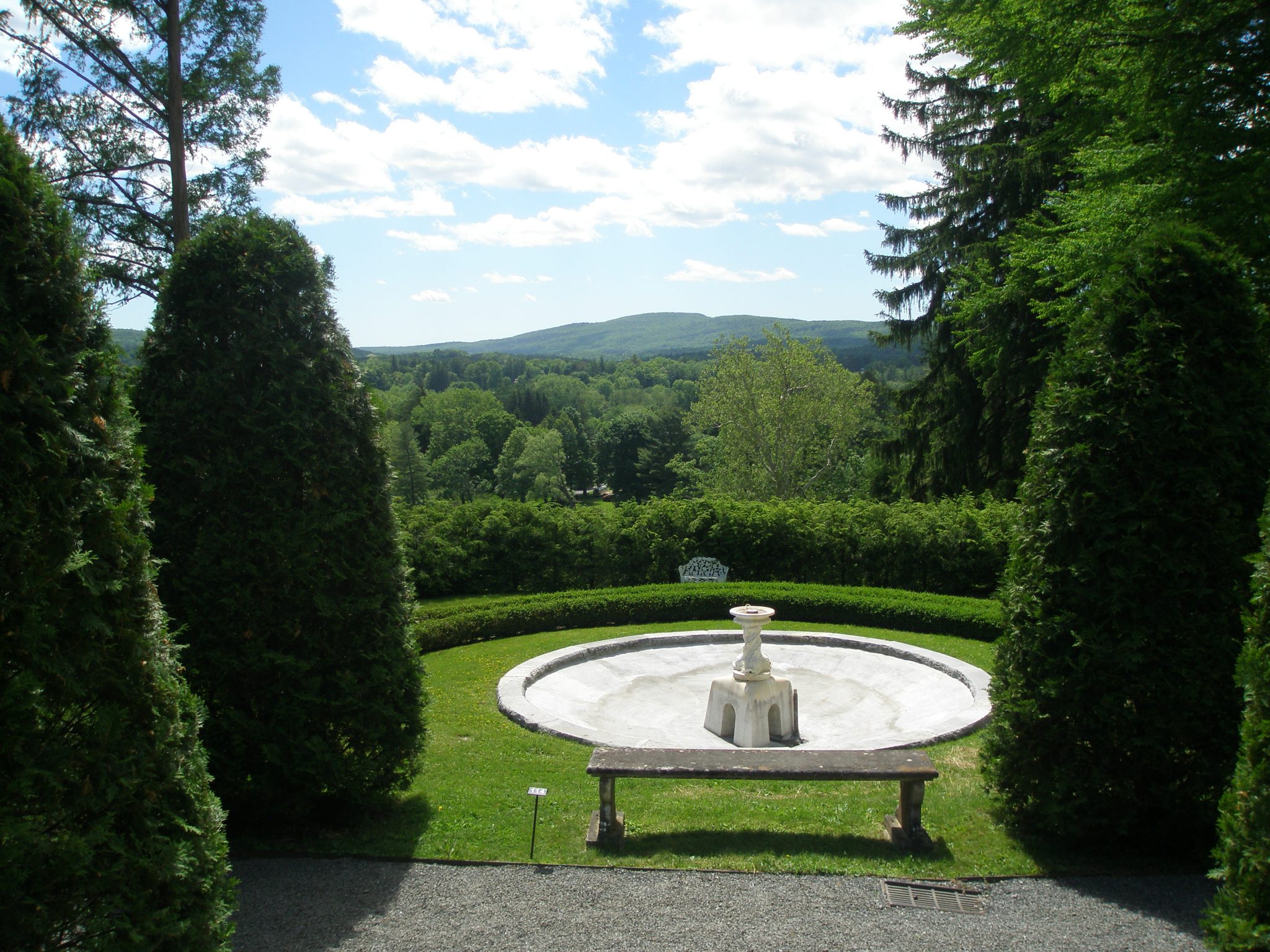

The Afternoon Garden, at Naumkeag, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts. Mabel Choate and landscape designer Fletcher Steele worked together for 30 years to develop the landscape around her shingle-style vacation retreat. The Afternoon Garden–begun in the late 1920s– was the first of many garden designs at Naumkeag that Steele did for Mabel Choate. In the distance, the South Lawn stretches out toward the Pagoda and the Linden Walk.

Birds-eye view of Afternoon Garden, drawn in 1930 by Henry Hoover, who worked for Steele.

Steele was a gifted designer, but a mediocre draughtsman.

Hoover’s renderings of Steele’s designs became an important sales tool; so expressive were his drawings that clients could see exactly how their finished

gardens would appear. Image courtesy of FLETCHER STEELE, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, by Robin Karson.

Fletcher Steele was a well-established landscape architect by the time his path crossed Mabel Choate’s, and his bounty of garden design commissions ensured that he could be selective when choosing clients. So…who was this design-despot; this person too persnickety to work for any client in possession of a less-than-elegant back door?

At first, it seemed that Steele might be destined for dilettantism. He was born in Rochester, New York, in 1885, to parents who were comfortably-situated and highly intellectual. Steele never felt less than coddled and adored: from the start, his idiosyncrasies and verbal precociousness were encouraged; as a self-defined “talker,” Fletcher learned that his powerful ability to chat and charm opened almost any door in life. Fletcher could easily have whiled his life away as a chatterer; by the time he was indifferently studying at Williams College his only apparent specialties were raconteuring and drinking…two skills which he continued to hone for the rest of his life. Steele was prone to depression and fussy about the company he kept, but altogether unimpressed by others’ wealth. He said “I decided that almost everybody was amusing but not bright. I have kept that opinion—reinforced it, rather. Also I think that education is much overrated.”

Graduated from Williams, Fletcher enrolled in Harvard’s recently-established program in landscape architecture, but stayed for only two years. It was afterward, during his six-year apprenticeship with Warren Manning–one of America’s best landscape architects–as Manning groomed Steele to be his right-hand-man-on-the-job and sent him out across America to supervise the construction of hundreds of commissions, that Steele matured and acquired the nuts-and-bolts skills which would eventually allow him crystallize his own thoughts about how his ideals of Beauty might be used to design landscapes that harmonized with those provided by Mother Nature.

In his unpublished essay, “Where Art and Nature Overlap,” Steele, highly analytical but also equally, intensely intuitive, wrote of his profession:

“It is not the thing itself with affects the landscape architect, but its bulk and position as related to the other matter round about it and to himself. Its individual virtues do not count if it is too large or too small or in the wrong place…this feeling that things are in the way where he wants free space or, conversely, that an open hole would be better if filled, is a strong component of his procedure when composing a landscape. Without it an equally agreeable pattern might be contrived… But for plastic quality derived from modeling the earth till it makes him feel good, fixing points of vantage higher or lower than suggested by existing circumstances and regulating the size and location of foliage masses, the landscape architect depends upon a physical sense refined until it is affected by solid material and empty space.”

Steele’s response to life—-simultaneously intellectual and sensual—-was an ideal combination of attributes for a designer of gardens and landscapes. It’s all good and well for historians that Steele was so voluble about his design philosophies (and SO exhaustive in his accounts of the trials and tribulations which accompanied the making of each of his gardens), but even if he hadn’t left behind masses of words, walking through the gardens at Naumkeag—his most important commission, and one of the very few of his more than 700 works which remains intact—tells the complete tale about how, over the course of thirty years, his vision developed. Steele’s work began as referential and derivative, and then broadened and refined itself into the abstract and lyrical.

Here now are my photos of Naumkeag, taken during the long, golden-lighted afternoon of June 4th, where—apart from the construction crews who were working on the millions’-of-dollars-worth of restorations across the grounds which have recently begun—I had the place virtually to myself.

I’ve organized Steele’s “rooms” at Naumkeag by their dates of inception, beginning with the Afternoon Garden, and ending with the Rose Garden.

AFTERNOON GARDEN—1928

Per Robin Karson, in FLETCHER STEELE, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT: “Roman thrones and matching footstools were constructed of concrete according to Steele’s design. Choate was a large woman, and after 30 years of sitting in those chairs she once remarked to him how horridly uncomfortable they were. ‘But Mabel,’ he replied, ‘you’re NOT supposed to sit in them, you are supposed to look at them!’”

Ahem…a digression. As a furniture designer, I beg to differ. Steele’s remark is an example of the worst artistic arrogance. Homes, gardens and furniture must serve and comfortably accommodate the humans who use them. To make furniture that’s beautiful but back-breaking is sheer laziness: the goal to which a designer must always aspire is to combine purity of line with comfort. Since Mabel Choate’s gardens were funded without financial limitations, Steele had no excuse for outfitting them with chairs that tortured her. Fie on Fletcher: in this one respect, he should have served his client better.

Now, back to more glimpses of the Afternoon Garden:

Frederick MacMonnies’ statue, YOUNG FAUN WITH HERON, perches on the Southwest corner of the Afternoon Garden

TOP LAWN—1932

The crumbling Great Seat, which is at the Southwest edge of the Top Lawn’s terrace. Mabel Choate’s guests converged here at day’s end, to watch the sunset.

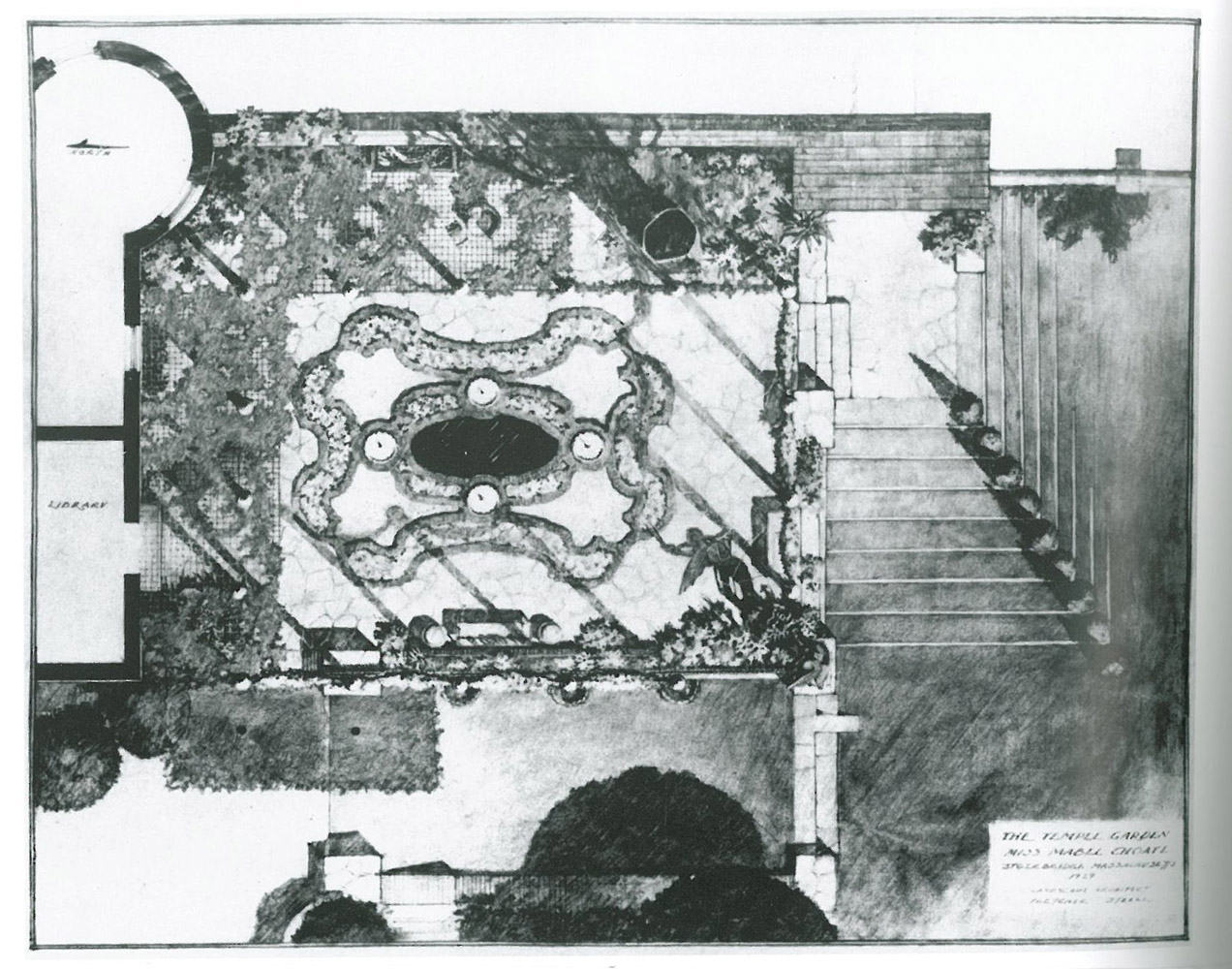

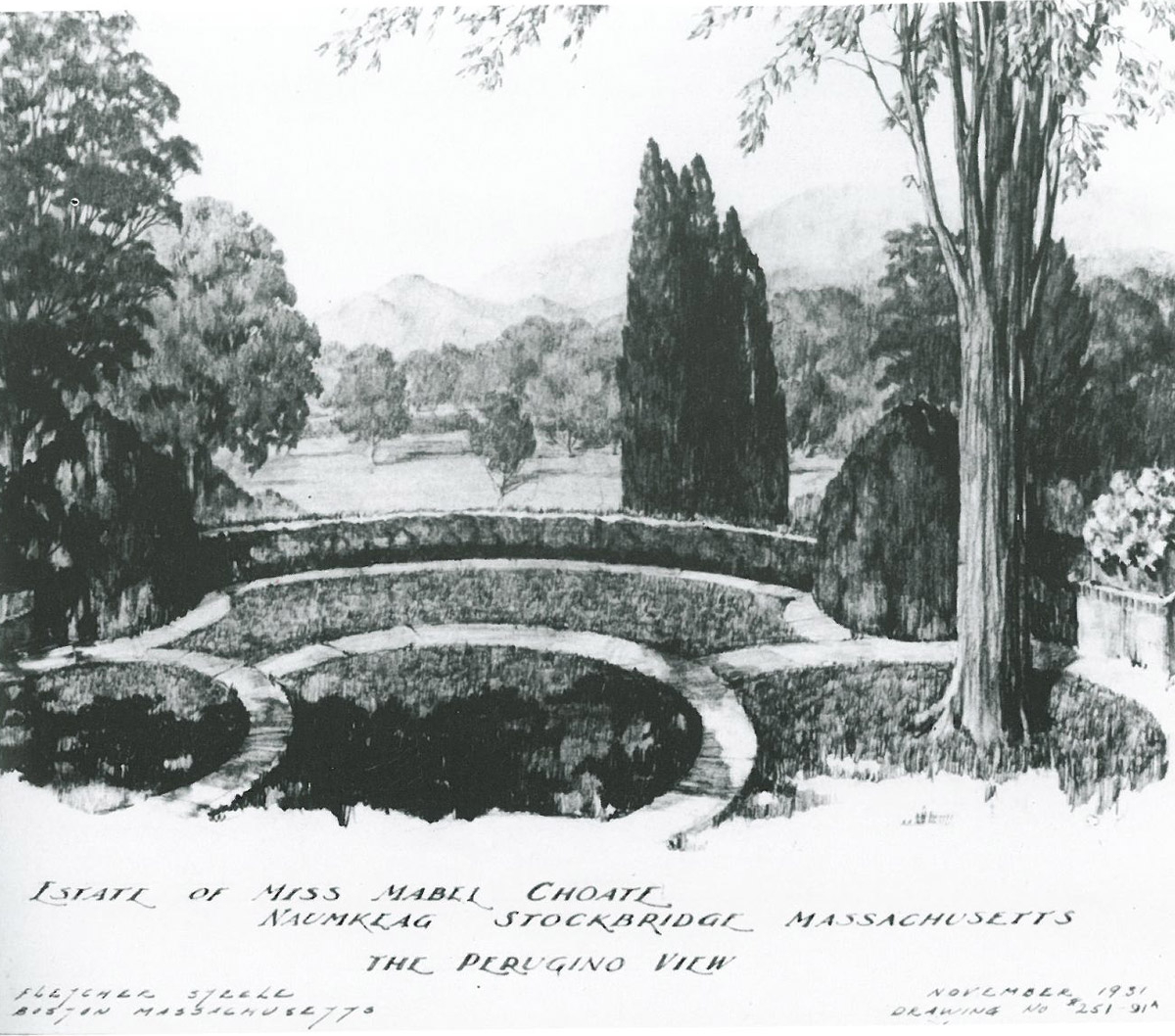

PERUGINO VIEW—1934

Henry Hoover’s drawing of The Perugino View. Image courtesy of FLETCHER STEELE, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, by Robin Karson.

Perugino View today:

foreground much changed, but with Monument Mountain still where it’s always been.

SOUTH LAWN & PYRAMID STEPS— 1933-1935

OAK LAWN—1935

TREE PEONY TERRACE—1935

Photo taken as the fieldstone terraces of the Peony Terrace–at the Southwest end of the Top Lawn–were being constructed. Image courtesy of FLETCHER STEELE, LANDSCAPE ARCHITECT, by Robin Karson

The Tree Peony Terrace. Perversely, Naumkeag is closed during peak-Peony-bloom-time. Perhaps in future years the Trustees of Reservations will decide to open Naumkeag at the beginning of May…for the peony-lovers?

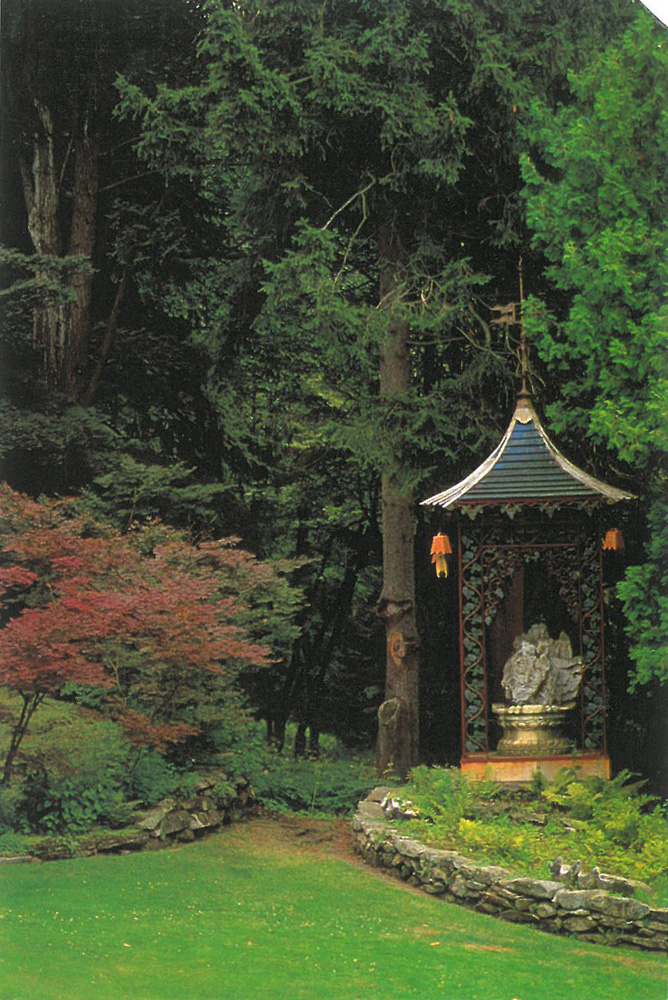

PAGODA—1936

WATER RUNNEL—1938

The currently-dry Water Runnel, which courses past the base of the Pyramid Steps and down toward the top of the Blue Steps

Once water resumes flowing in the Runnel, it will pour into the system of waterfalls and fountains that course down alongside the Blue Steps

THE BLUE STEPS—1938

I ignored this sign…but later on asked the construction crew for permission to trespass…which they kindly granted.

All of the old birch trees surrounding the Blue Steps have been removed, and on June 4th, the final batch of new trees were being hoisted into place.

The site of Mabel Choate’s former cutting and vegetable gardens, at the base of the Blue Steps. Once the trees that are being stored here have been transplanted around the Blue Steps, these defunct gardens will be recreated.

Even in the Blue Steps’ unfinished state, stairs and water and railings and birches and shadows meld…

CHINESE GARDEN— 1936-1955

From inside the Chinese Garden, one can peer out toward the Western hills through perforations in the masonry.

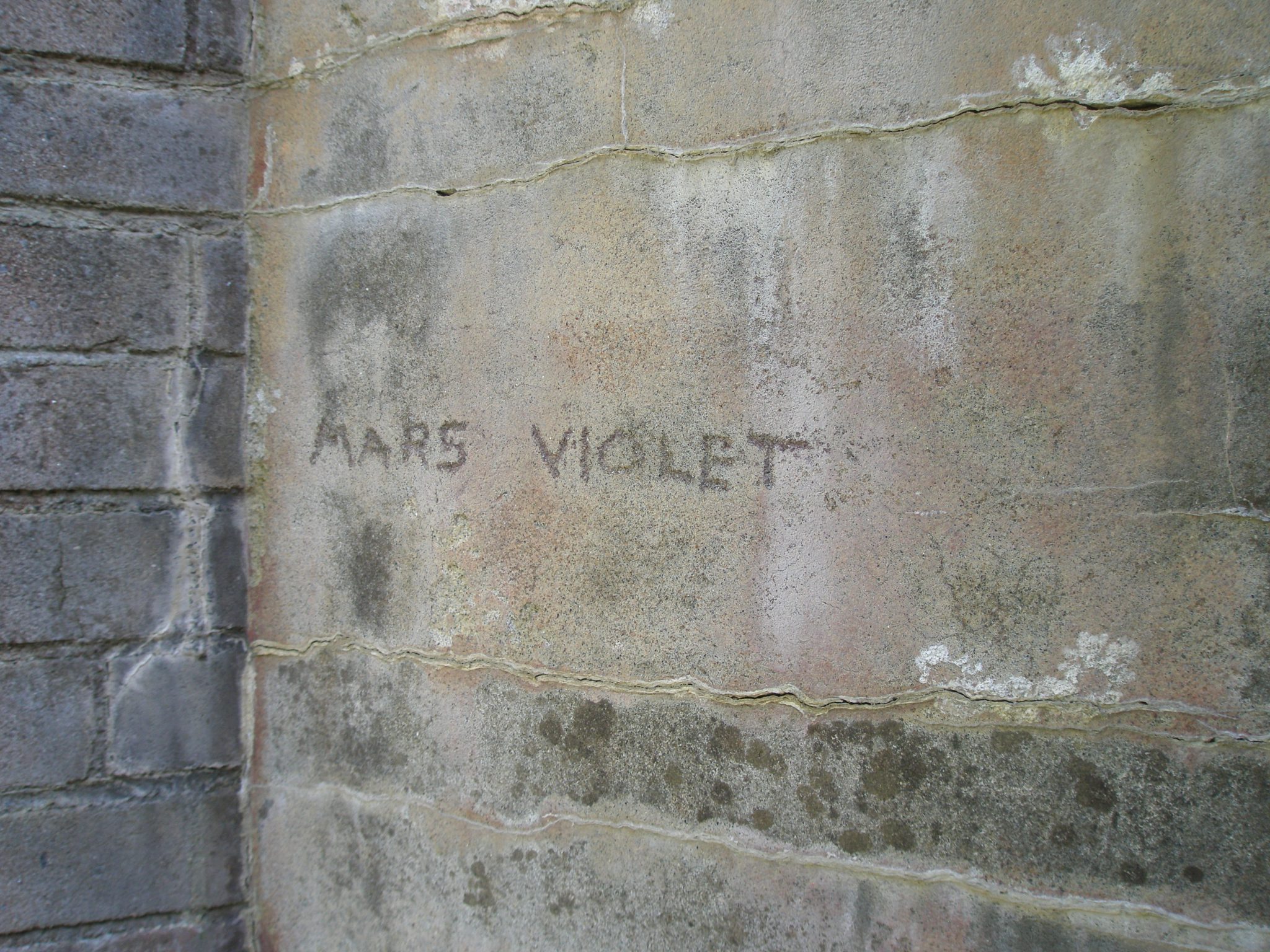

Fletcher Steele was specific about the colors to be painted upon the Chinese Garden’s Wall. His instructions are etched into the wall.

MOON GATE— 1955

View from the Chinese Garden, out through the Moon Gate, toward my Trusty Chariot, and the Choate House.

ROSE GARDEN— 1953-1955

Rose bushes, past their blooming-prime, always manage to look scabrous.

Steele’s still-to-be-restored Rose Garden cleverly distracts us from dwelling upon forlorn and bloom-free branches. Once things here have been spruced up, we’ll be able to admire the undulations of freshly-installed pink gravel, contrasting with green grass. The presence or absence of flowers will be irrelevant.

The Rose Garden was designed to be seen from above. Here, the view from the walkway at the lower edge of the Top Lawn.

The Curves of Roberto Burle Marx’s 1970 pavement design for the boardwalk at Rio de Janeiro’s Copacabana Beach. I’ll bet anything that Mr. Marx had seen

photos of Naumkeag’s Rose Garden.

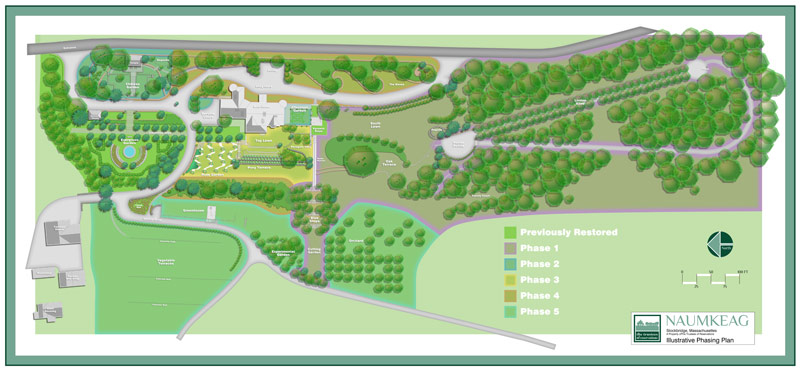

The Trustees of Reservations, who now own and manage Naumkeag, and who have recently begun a three-year, 2.6 million dollar process of garden restoration, make this apology about the current state of the property:

“Fletcher Steele’s intricately detailed, finely crafted gardens are in need of polish: plants are aging, views are diminished, and harsh New England weather has taken its toll on this landmark.”

But during the four, nearly-solitary hours I spent at Naumkeag in early June, I felt that the Essence of the Place was intact and very much alive…and that no apologies by the Management were necessary. The stylistically various elements of the gardens that Steele knitted together over three decades for Mabel Choate—a great lady whose outlook was international, and to whom we must endlessly give thanks for WANTING such wonderful gardens to be created—merge harmoniously, despite the intense individuality of each of the garden “rooms.” Whether we’re sitting in the Afternoon Garden (where nonsensical, landlocked Venetian gondola posts support swags of vine-covered rope, and a Baroque knot garden serves as a watery carpet) , or climbing up the Blue Stairs (where shadows and the objects which cast them seem to merge) , or gazing down at the Rose Garden (which, almost Dali-esque, seems more a Dream of a Garden than a place of actual dirt and plants), or ambling across the Oak Lawn (where the sinuous line of the cedar-post retaining wall…abstract and sculptural…mimics the profile of the distant hilltops), each of the various aspects of Naumkeag BELONGS on this particular hillside, and to this particular, be-shingled house. The unity of Steele’s masterwork came about because he NEVER forgot to link his foreground with the background. Here, to prove that God is always in the details, just a few more examples of Steele’s meticulous eye:

NAUMKEAG.

House & Gardens are open daily from Memorial Day weekend to Columbus Day. 10AM—5PM. 45-minute guided tours of the house. Self-guided tours of the gardens. There is a nominal admission fee. The driveways on the property can accommodate only a few vehicles at a time….you’ll NOT find tour-bus crowds at Naumkeag.

5 Prospect Hill Road, Stockbridge, Massachusetts 01262

(413) 298-3239 www.thetrustees.org

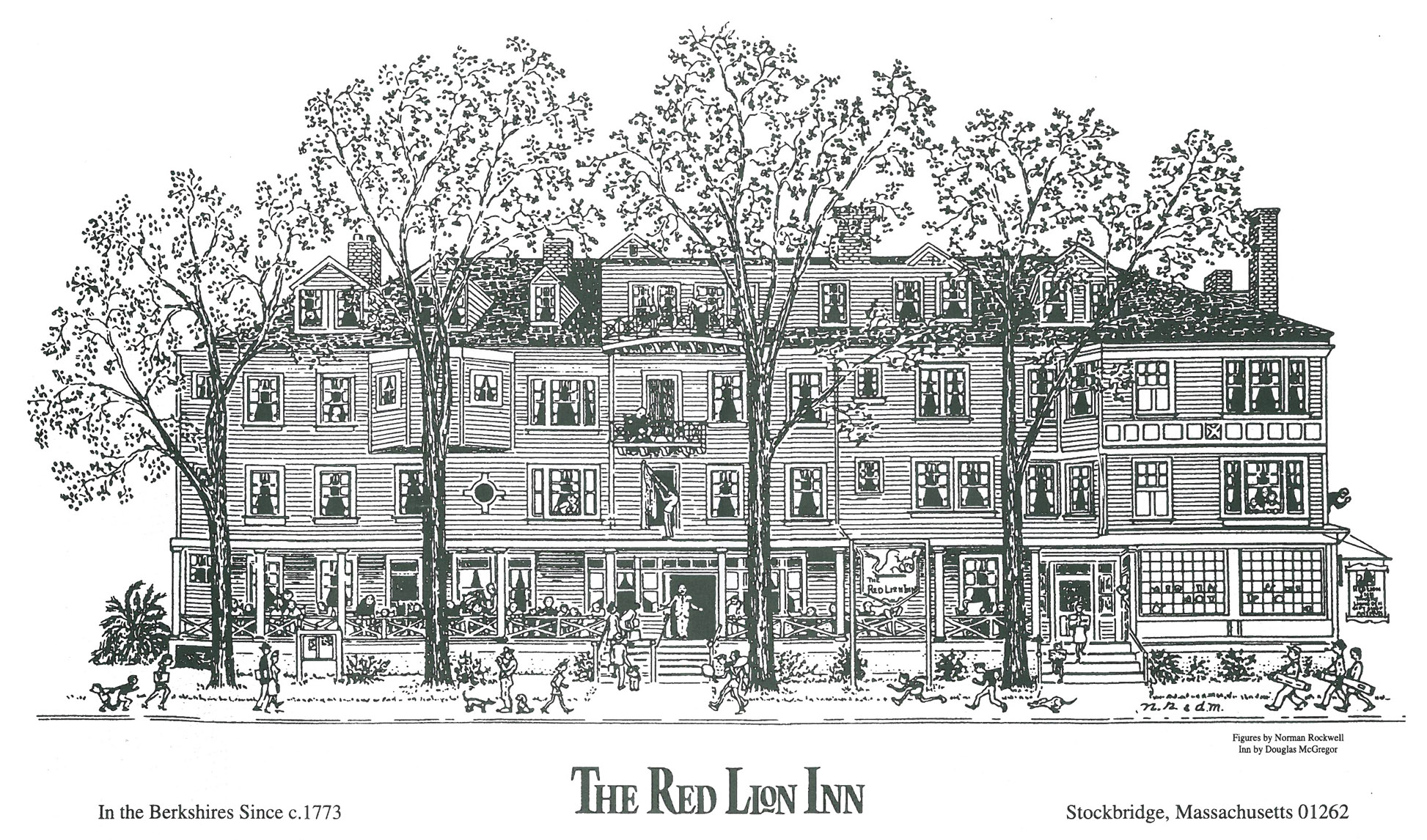

That evening, my head still abuzz with thoughts about my afternoon at Naumkeag, I hunkered down at The Red Lion Inn, in Stockbridge. Happily, my room had a big bathroom…with an enormous tub…and so I was able to calm my brain with a long soak. The Red Lion isn’t fancy—it’s actually a fudgy old pile of a place, which doesn’t seem to have been spruced up much since its last major redecoration, which occurred in 1956. BUT, for the past 241 years, the Inn has been THE place to rest one’s head while in Stockbridge. (A Short Inn-History:1773—first Inn built, to which higgledy-piggledy additions were made. 1886—Fire destroys entire building. 1887—Inn rebuilt into the same, rambling pile which accommodates us today.)

Wednesday morning, after I’d fortified myself with a farmer’s-sized breakfast at The Red Lion, I headed North toward nearby Lenox, Massachusetts, to see The Mount, Edith Wharton’s famous country home.

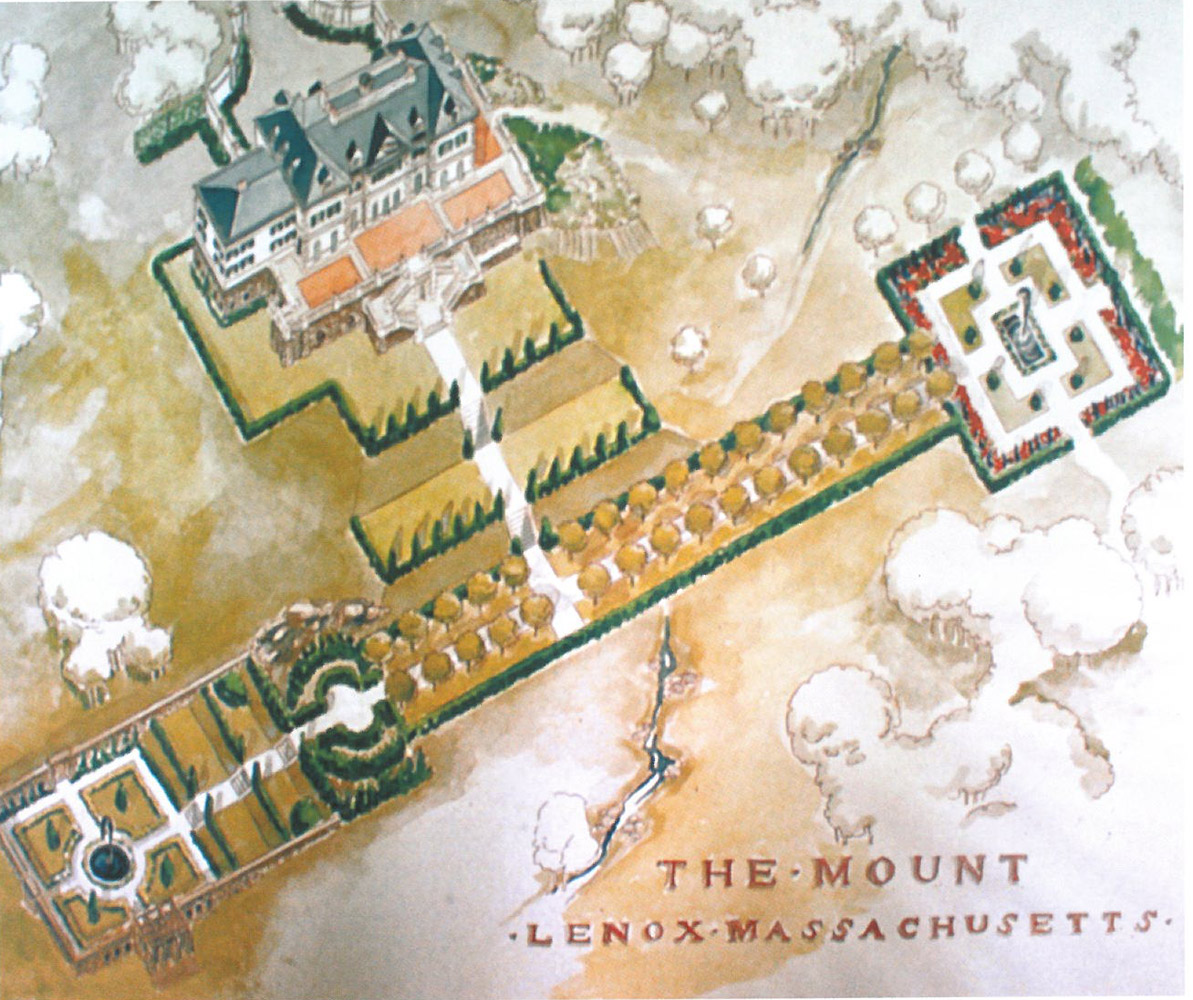

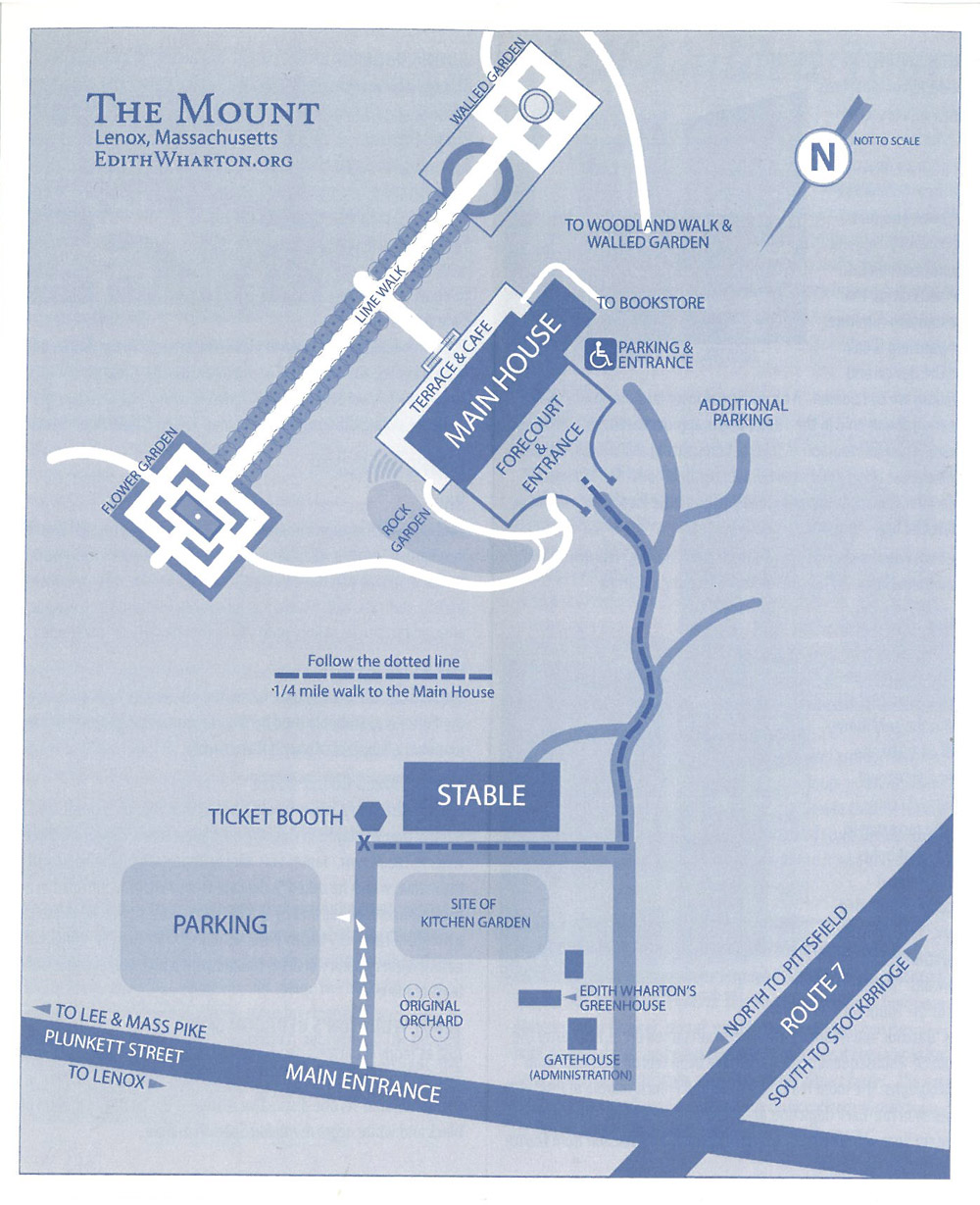

A Falcon’s View of The Mount. Image courtesy of “Edith Wharton at Home: Life at The Mount,” by Richard Guy Wilson.

Unlike Naumkeag, which, surprisingly, is unknown to the masses, The Mount is much-celebrated, and is thus a favorite stop for the tour-bus mobs. But I arrived at opening time sharp, and was able to walk alone through the manicured woodlands and gardens that surround the Main House.

To welcome visitors to The Mount, The Edith Wharton Foundation compresses Wharton’s amazingly-productive existence into these two paragraphs:

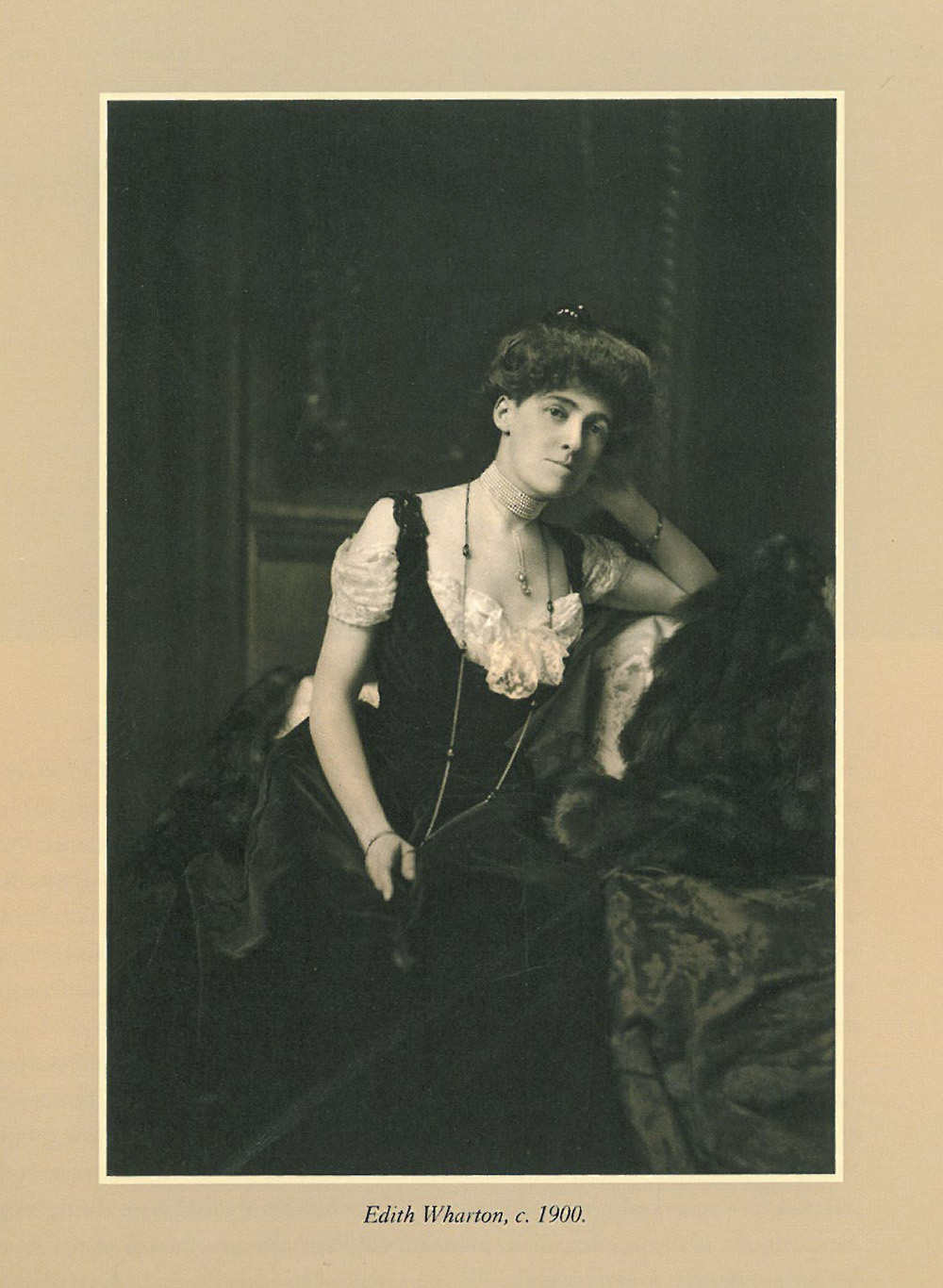

“Edith Wharton (1862-1937) was one of America’s greatest writers, producing over 40 books in 40 years, including novels, collections of short stories and poems, and authoritative works on architecture, gardens, interior design, and travel. She was the first woman awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Fiction, the first woman to receive an honorary doctorate from Yale, and the first woman elevated to full membership in the American Academy of Arts and Letters.”

Edith Wharton, as she was busy planning her Dream Home. Image courtesy of “Edith Wharton at Home:Life at The Mount” by Richard Guy Wilson.

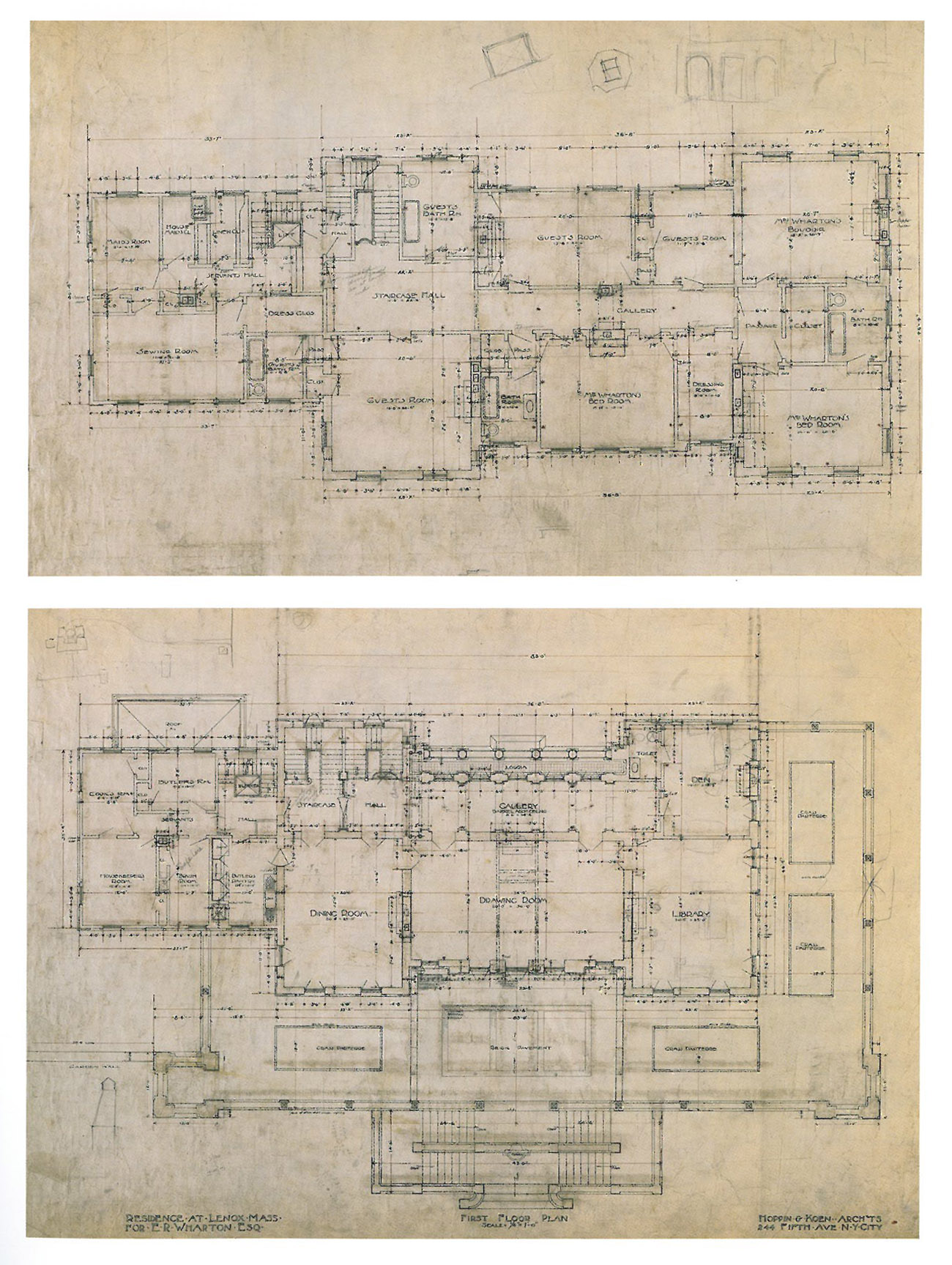

“Wharton designed and built The Mount. Though she was already 40 when she moved in in 1902, she considered it to be her ‘first real home.’ Five years before, she had published THE DECORATION OF HOUSES, in which she and co-author Ogden Codman, Jr. denounced the excesses of Victorian interior decoration and urged a return to the classical virtues of proportion, harmony and simplicity. The Mount became a laboratory for exploring [her design] principles. Wharton worked with architects…in planning the house, but it is clear that she orchestrated every detail and was ultimately The Mount’s designer.”

But, before visitors can gaze upon Wharton’s turn-of-the-century homestead, they must first walk past the Stable…

…and then ramble through the woodlands that flank the long, maple-lined approach drive, which was designed by Wharton’s niece, the noted landscape architect Beatrix Farrand.

Beatrix Farrand, Edith Wharton’s niece. Note: I’ve written about Farrand’s work before, when I covered her masterpiece, Dumbarton Oaks, in my July 2012 article for New York Social Diary, titled “Gardens & Estates Along the Potomac.” In a future Armchair Diary article, I’ll revisit Dumbarton Oaks, for an early-Springtime look at those Georgetown gardens.

On that sunny June morning, as shafts of sunlight pierced the tree canopy and birds chittered, I discovered these contemporary sculptures, which are carefully-sited throughout the grounds. This soon-to-close outdoor exhibition, titled “2013–Sculpture Now at The Mount,” consists of large-scale pieces by 24 nationally-acclaimed artists, and reflects the Edith Wharton Foundation’s goal to transform The Mount into a place that doesn’t just look backwards toward Wharton’s artistic achievements; there’s room at The Mount—both physically and spiritually—for plenty of new creative energy and work.

Eyes invigorated by my sculpture-stroll, I approached Edith Wharton’s gardens, which she herself designed. Wharton–well-traveled, and much-opinionated about the grand gardens of Europe–boasted to friends that she considered herself a better landscape gardener than a novelist. As she laid out her gardens at The Mount, Wharton was also working with the illustrator

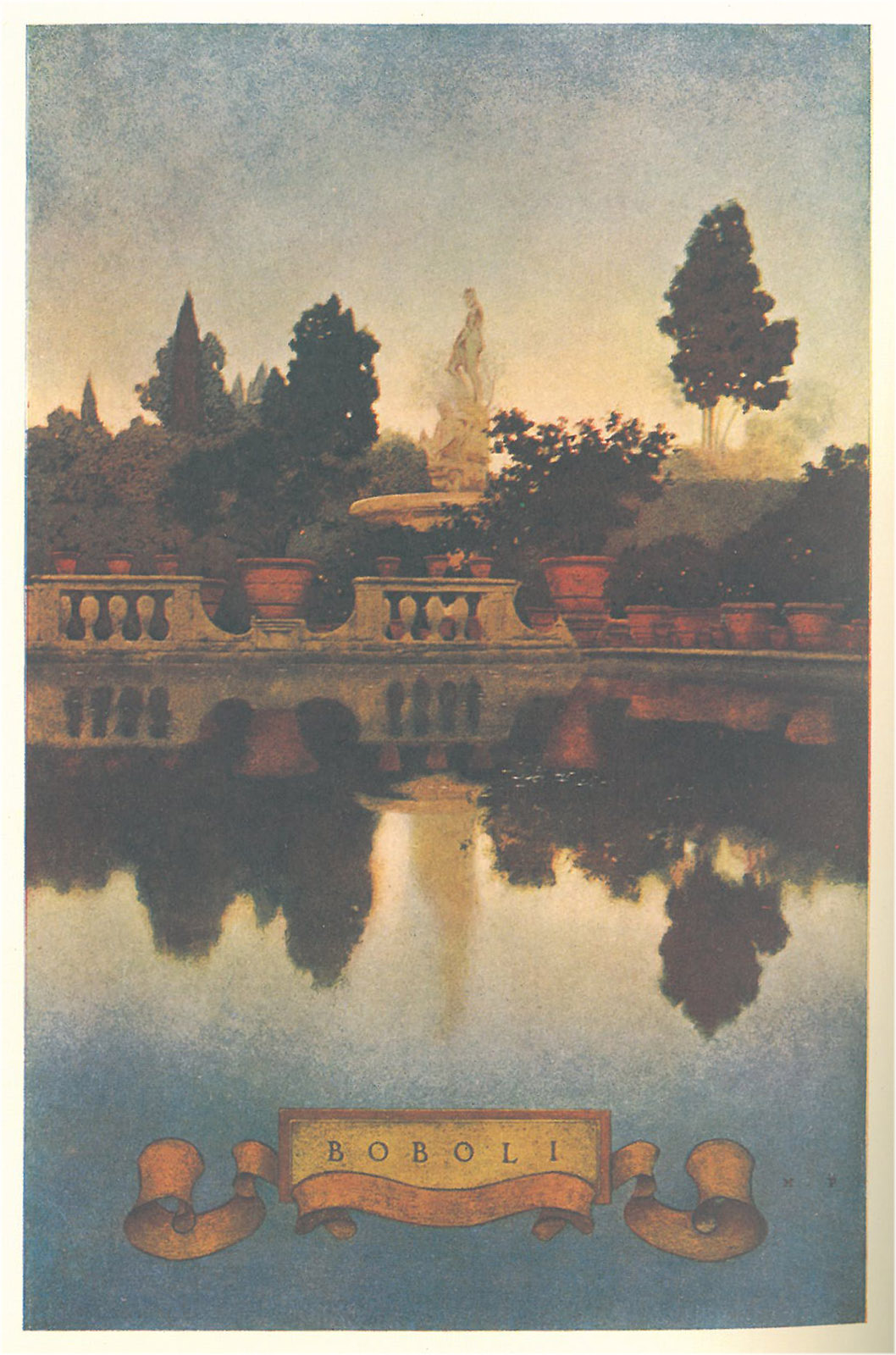

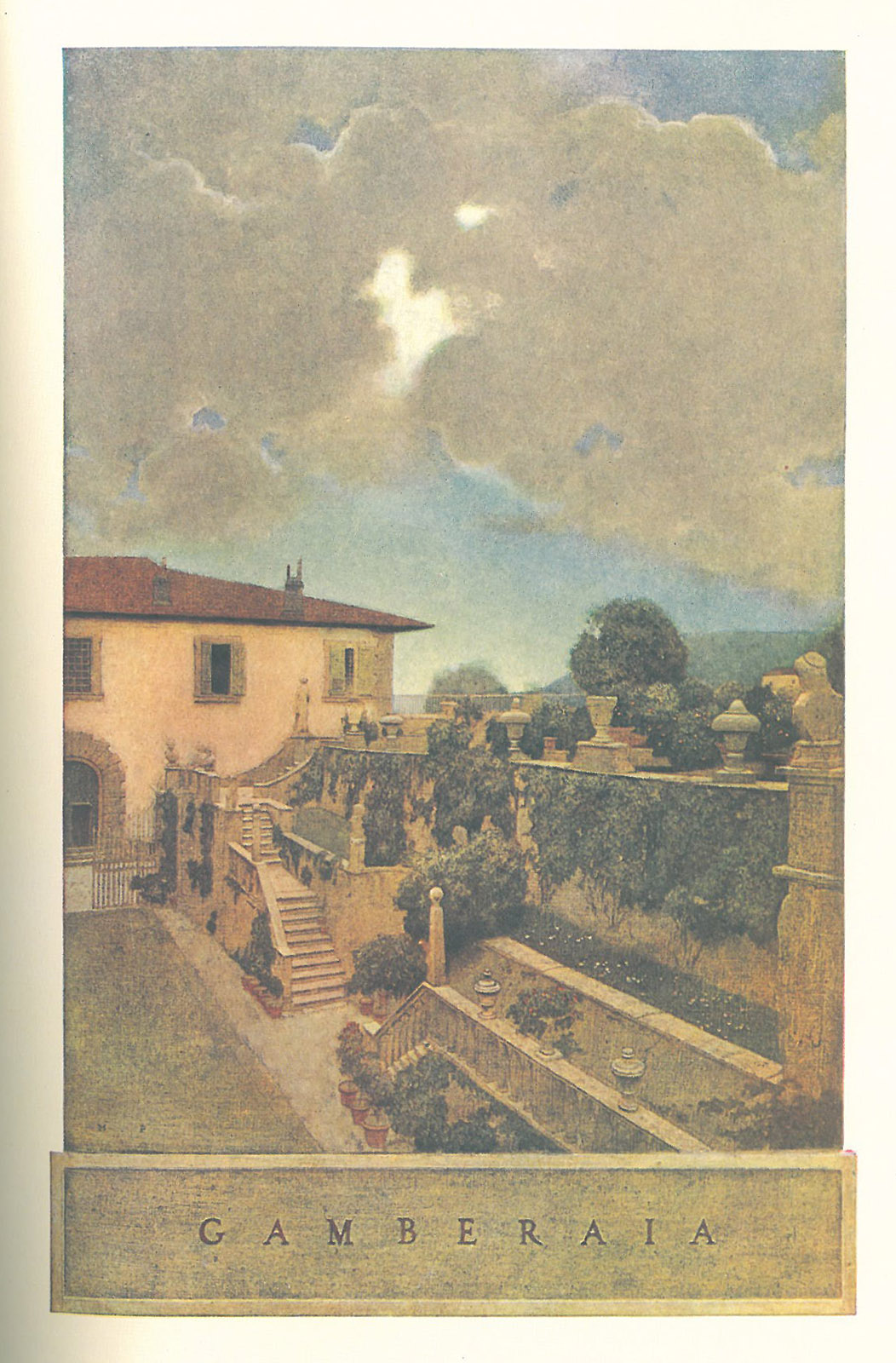

Maxfield Parrish on her book, “Italian Villas and Their Gardens.”

My Constant Readers will recognize both the Boboli Gardens, and the gardens of the Villa Gamberaia at Settignano, from my earlier Armchair Diary, “Florence & Lucca: The Villas, Gardens & Treasures of Tuscany.” And really observant Readers will recognize the water gardens of Gamberaia as the header photo which I use for all of my Armchair Diaries. SO….Edith…Beware! I KNOW my Italian gardens well. I advanced skeptically toward Edith’s gardens, the ones in which she said she aimed to distill and surpass all of the garden-lessons she’d learned during her Italian travels.

I offer my Verdict first…there’s no point in a Long Tease. Wharton’s gardens are banal, and the siting of her lumpish house is awkward. I much prefer her writing skills to her designing skills. (And My God…if you’ve read Wharton’s erotic stories, you’ll blink, rethink your image of Edith as a stuffed-shirt, and then set her alongside Anais Nin as the OTHER greatest Goddess-of-Love-Writing!) But Wharton’s not-so-good-landscape-design serves as a necessary contrast, one which makes a garden-seeker all the more appreciative of truly inspired spaces…such as those which Naumkeag presents.

Here now, a tour of Edith Wharton’s perfectly-nice, but uninspiring Gardens, which, after much restorative work, once again appear as they did when they were new.

View from Terrace, down over the Rock Garden’s Grass Steps, toward the Flower Garden, and The Lime Walk

As I ambled through The Mount’s gardens, I felt as if I were exploring a country club, and not a home. Every aspect of The Mount’s landscaping feels institutional, rather than domestic. Perhaps the interior of Wharton’s home would feel less bland? I joined a small group of fellow visitors at the Forecourt of the Main House, and waited for our tour to begin.

House Plans for the Main Floor, and for the Bedroom Floor of The Mount. Image courtesy of “Edith Wharton at Home: Life at The Mount,” by Richard Guy Wilson.

The Ground Floor Entrance Hall was conceived as a Grotto, with stylized plaster-work simulating mossy, water-soaked walls.

Gallery, on Main Floor. This was essentially a hallway, along with a place for the display of the objects that Wharton collected on her European travels. The floor is terrazzo.

Decoration over the door in the Gallery that leads to the study of Wharton’s ineffectual husband, Teddy. Teddy’s story is long and depressing…suffice it to say that Edith eventually had to leave him, along with her beloved home.

This bas relief depicts John the Baptist as an infant.

Edith Wharton’s Library on the Main Floor. Wharton liked to gather friends here for literary readings.

Drawing Room on the Main Floor. This is the largest room in the house, measuring 36 feet long by 20 feet wide. Brussels tapestries are set into the walls.

Another view of the Drawing Room, which has the most elaborate ceiling treatment of all of the house’s rooms. Our Guide is holding forth, in front of the fireplace. She was vivacious, charming and FULL of information about Mrs. Wharton and her home.

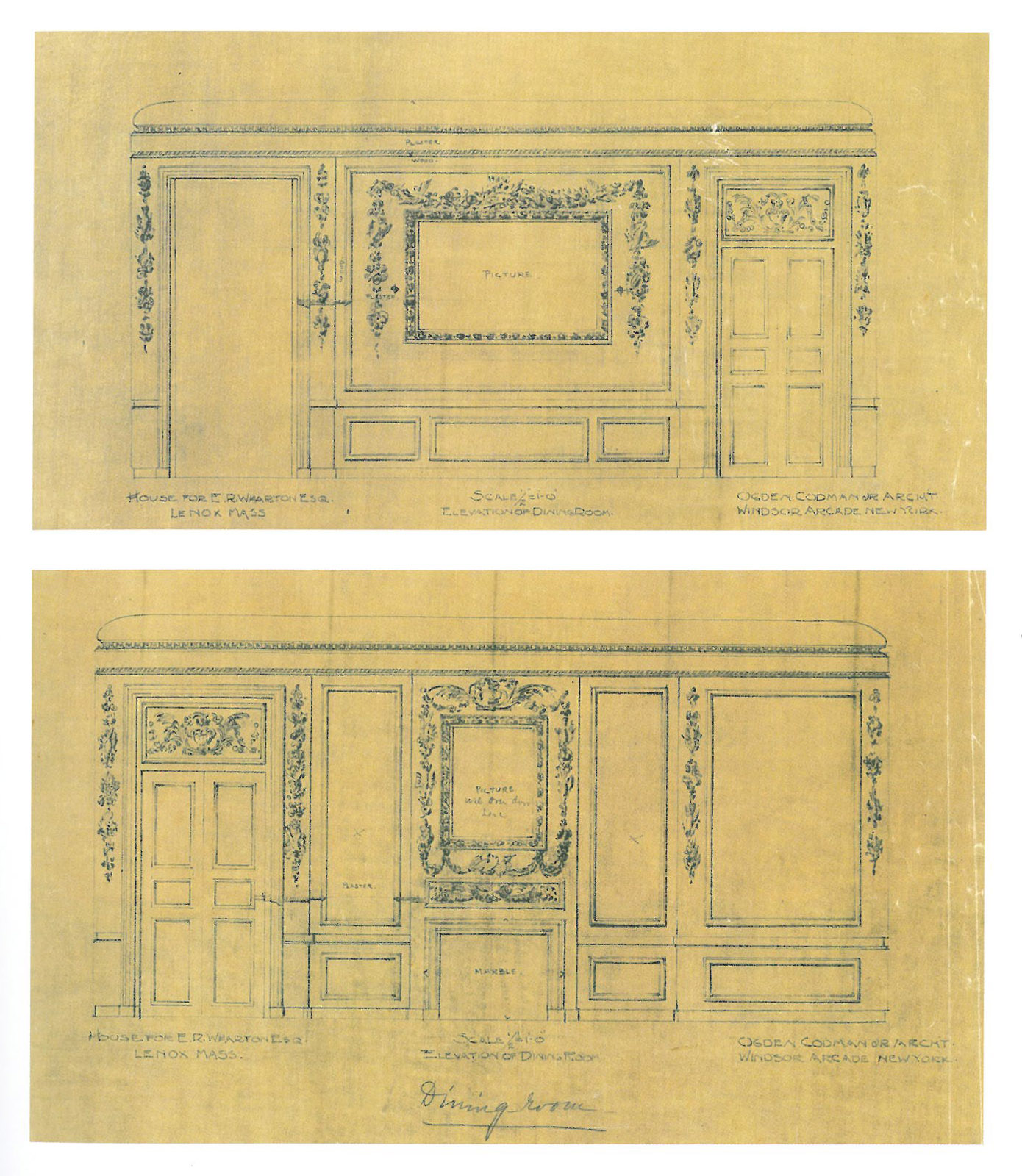

Dining Room on the Main Floor. This is my favorite room in Edith’s home: airy & humorous & clearly a great place for a party! Wharton believed that decorations for a dining room should reflect the food eaten there, and so the walls are gaily festooned with plaster garlands of fruits, birds & fish. Fabulous!

Elevations for the Dining Room. Image courtesy of “Edith Wharton at Home: Live at The Mount,” by Richard Gus Wilson.

A contemporary sideboard decoration in the Dining Room…quite in keeping with the jolly vibe of the room.

Edith Wharton’s Boudoir–or Sitting Room, which is on the Bedroom Floor. The Boudoir was designed by Odgen Codman, Jr., and is the most elaborately-outfitted room on the Bedroom

Floor. The room is dominated by 8 floral still-life paintings set into paneling, which was imported from Milan.

Edith Wharton’s Bedroom.

Wharton did most of her writing in this room; she would awaken early and write in bed, dropping the finished pages to the floor, where her secretary would eventually collect them. The Bedroom furnishings we see today are not originals…no one alive knows exactly what this room looked like during Edith’s tenure at The Mount. Interior decorators have followed the design rules in “The Decoration Houses,” and are confident that the rather spare appearance of the room is in keeping with Wharton’s design approach.

So, is traveling to Western Massachusetts expressly to visit The Mount’s gardens worthwhile? Probably not, especially since the contemporary sculpture show in the woodlands is about to be dismantled. But if your primary interest in Wharton is literary and historical, then a visit to Lenox will be rewarding. And although the exterior architecture of The Mount is lumpish, some of the interior spaces come close to being divine (i.e. The Gallery, and The Dining Room), and even in rooms that aren’t perfect there are many fine little design-innovations to appreciate. Wharton’s then-radical tenets of house decoration (remember, she was rebelling against suffocatingly-overstuffed Victorian rooms) look rather unremarkable today, but she was championing a simplicity (I know….”simplicity” when a very wealthy person is fashioning a home for herself is rarely a humble thing) that, over the decades since she built The Mount, has been hugely influential.

THE MOUNT.

House and grounds open from early May until Halloween.

10AM to 5PM. Arrive early, as I did, and you’ll have the place to yourself.

And, year-round, there are lectures and programs which celebrate Wharton’s

many passions: the literary arts, interior design and decoration, garden and landscape design, and the art of living well.

2 Plunkett Street, Lenox, Massachusetts 01240

(413) 551-5111 www.edithwharton.org

Copyright 2013. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express &

written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

4 Responses to Grand Gardens of the Berkshire Hills: Fletcher Steele’s Naumkeag, & Edith Wharton’s The Mount