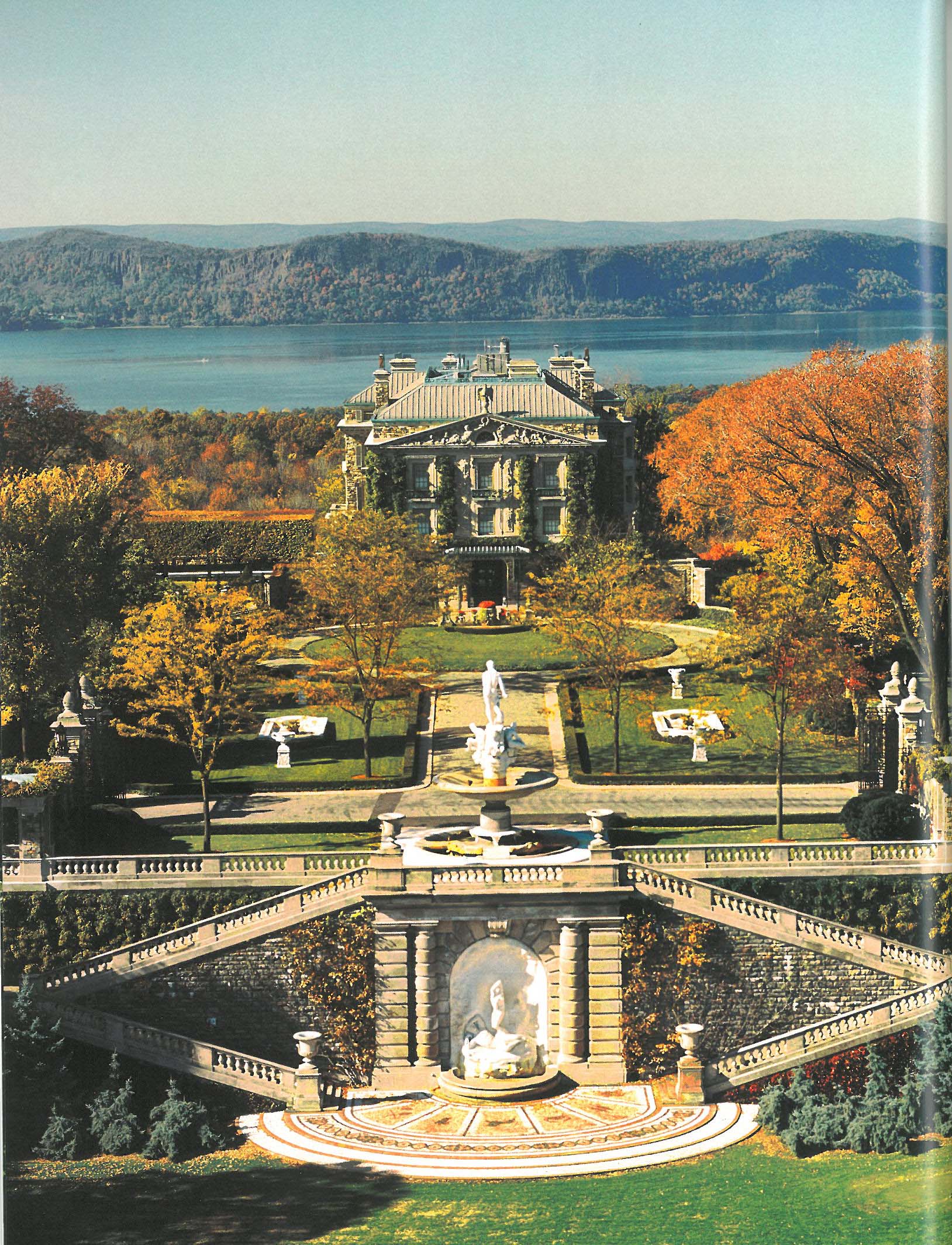

Kykuit: The Rockefeller family home. Entrance Forecourt, with the Oceanus Fountain, on a rainy morning in June.

December 2013. The impulse to collect–whatever one happens to want to accumulate—is powerful. As one hunts for treasure, each discovery, rather than satisfying, seems instead to whet the appetite; after all, treasures exist most properly in troves. Humans are greedy souls.

At first glance, the shaggy, encyclopedic collection of plants at Stonecrop Gardens (which perch upon rocky ledges and around deep ponds in the wilds of Cold Spring, New York State), and the spit-polished and densely-decorated gardens at Kykuit (which cap a manicured hill near a wide point in the Hudson River), seem to have little in common. But in each garden we see the results of passionate collecting: of the horticulturalist Frank Cabot’s 52-year-long lust to acquire and grow aquatic and alpine plants, herbaceous perennials and bulbs, and rare trees and shrubs; of the Rockefellers’ three-generation-long hunger to amass sculpture—both classical and modern—along with all the other garden trappings befitting a world-class family seat.

I am not immune to this Collecting-Mania. But instead of piling up Property, I travel to beautiful, built environments…where I gather sensations, and ideas, and images. I have faith that, by temporarily inhabiting these places, I’ll somehow hear whispers from the people who created them; that the trees and terraces and landforms and lakes and follies and fountains and gardens and grottos in each spot I discover will have vestigial voices which will reveal to me the reasons, and more-interestingly, the passions, that drove their makers to plant and to build. My hope is always that each of these destinations will feed my eyes, and my brain, and my imagination. I want to be reminded that, despite mankind’s propensities for destructive behavior, we are also an inherently creative, and thus redeemable, species. Such is the nature of MY greed. But merely amassing these International-Catalogues-of-Gorgeousity for myself would be an empty exercise. I’ve discovered that the deepest pleasures from my travels come later, when I’m home again, in my office (where I’m nearly overwhelmed by my thousands of photos, and piles of books, and sheaves of notes), as I try to make sense of the wonders I’ve seen, so that I might share them.

In early June, after visits to two gardens in Western Massachusetts (Naumkeag, and The Mount), and then a stroll through the sublime Innisfree Garden (in Millbrook, New York), I drove southward, on the Taconic Parkway. Darkening skies and a predicted torrent meant that my camera would capture no more postcard-pretty photos during the final days of my journey, but I continued on into the Hudson Highlands, toward Stonecrop Gardens, with my raincoat and boots at the ready. For dirt-gardeners here in the Northeast, visits to Stonecrop are not so much pleasure-jaunts as plant-pilgrimages.

Stonecrop Gardens, on the rocky hills to the east of the Hudson River. In Cold Spring, Putnam County, New York State

In 2011, when Francis (Frank) H. Cabot died, his obituaries identified him, first and foremost, as “86, and an extraordinary gardener.” Born wealthy, into a family who specialized in investment banking, Cabot was never completely at ease with his role as a venture capitalist. In 1959, stressed by work,(he considered himself a great promoter, but not a particularly great picker, of start-up businesses) he threw himself into gardening, where he found his true calling.

Cabot is most famous for his ambitious landscape at Les Quatre Vents (The Four Winds), where he fashioned highly formal gardens on 28 acres that lie alongside the St. Lawrence River. Those gardens in Quebec are open to the public for only four days each summer, but can be vicariously enjoyed by reading Cabot’s book about his decades-long modeling of the land at his Canadian retreat: “The Greater Perfection: The Story of the Gardens at Les Quatre Vents.”

But for those of us who haven’t time to get to Quebec, or the wherewithal to fund our little reproductions of corners of those dauntingly-lovely gardens, the gardens that sprang up willy-nilly around his summertime home in Cold Spring, New York, can offer Normal Human Gardeners the consolations of buying Stonecrop’s quite-affordable plants, which are grown on the premises.

The steep, twisting, rutted, gravel road that leads up to Stonecrop Gardens made me very glad for my vehicle’s all-wheel-drive. There’s nothing flashy about Stonecrop; this is a place where the well-being of plants takes precedence over the coddling of visitors. At the edge of the car park, an Entrance Pavilion pointed the way, and I clattered over a wooden boardwalk, into deep woods.

At the end of the Boardwalk, the charming scene of a Pond Garden unfolds.

Iris, Petasites and Ligularia dominate the waterside plantings.

And then, framed by white birches, a Conservatory hovers, reflected in the water.

The Conservatory spans the pond, and serves as bridge into the Gardens proper. As is so often the case in my wanderings, I had this place to myself. I was far outnumbered by Stonecrop’s gardeners, who were quietly eradicating weeds, and pruning perennials. All I could hear were birds twittering, horses whinnying, and the sound of a gentle rain, shooshing down over the dense foliage.

I’m about to pass through the Conservatory. This building was completed in 1997. In winter and spring it is used as a display house for a winter garden of non-hardy blooming bulbs, trees and shrubs, many of them native to South Africa, Australia and New Zealand (Frank Cabot had a sheep station in New Zealand, and thus collected many plants there.)

On the Left: The Potting Shed, which is the heart of Stonecrop. Most of the Garden’s propagation work occurs here, throughout the year.

Their love of all-things-French influenced the design of Frank and Anne Cabot’s Main House.

Approaching the Main House at Stonecrop. The grass island in front of the house features a Pin Oak, underplanted with a sheet of Crocus, which blooms in early April.

West of the Main House, a broad vista unfolds.

To the south of the Main House is the Enclosed Flower Garden, which contains a jungle of flowers and veggies. When the Cabots built their home in the early 1950’s, the gardens began simply: Frank made raised stone containers for his alpine plants, and Anne tended flowers and vegetables. But soon, tons and tons of flint stone began to be extracted from the woods. With that stone, walls rose. And ponds were dredged, and streambeds formed. Very rapidly, Stonecrop became much more than a plaything for its summer residents.

But the Stonecrop that’s evolved into the place we see today is as much the creation of Caroline Burgess, as it is of Cabot. In 1985, Burgess, an Englishwoman who cut her horticultural teeth as an apprentice in Rosemary Verey’s Cotswolds garden, and then became a professional plant-wrangler at the Royal Botanic Gardens at Kew, was hired by Frank Cabot, who gave her carte blanche to develop his tree and shrub collection. By 1992, Cabot admitted, “It’s really hers now.”

Per Stonecrop’s guide to their gardens, the Enclosed Flower Garden, has “a series of color-themed square and triangular beds. These beds, together with the surrounding enclosures and permanent plantings of hardy perennials, roses, grasses, tress and shrubs, create a formal framework in which to display intermingled informal plantings and annuals, biennials, and half-hardy and tropical plants. Constant experimenting with color and plants yields new combinations every year. Four of the square beds have steeple trellises on which grow annual and perennial vines, giving vertical accent to the garden. The walls surrounding the enclosed garden are planted with …espaliered shrubs and climbers. A vegetable garden fills the largest bed in the middle of inner sanctum, and is watched over by Miss Gertrude Jekyll, who is keeping an eye on the color theories. Behind Miss Jekyll, linked by a circular path, curved beds represent the colors of the rainbow.”

What a Perfect Flower looks like (Hmmmm….mine never look this good, and are always infested with ants).

The most dramatic area at Stonecrop is the Lake, which is surrounded by the Hillside, and Rock Ledge Gardens. Per the Stonecrop Visitor’s Guide, “ With the exception of what is clearly massive rock ledge, all the rocks in this garden were placed, the smaller ones by hand, and the larger by machine. The Lake and surrounding landscape were finished in 1991. From the Rock Ledge, the land originally sloped down to the fields below. To give a natural surrounding to the new lake, fill was trucked in….to achieve the current landscape.”

In 1984, Cabot had a Wisteria Pavilion built at the south end of the Lake.

As is apparent, Stonecrop Gardens is not a place of Grand Vistas, of Endless Allees, or Tidy Parterres. Apart from the picturesque buildings which decorate the 12 tightly-packed acres of its display gardens, Stonecrop’s truest beauties are most apparent when the visitor inspects the ground, square-cultivated-yard by square-cultivated-yard. The most serious gardener will take copious notes as she surveys Stonecrop’s Systematic Order Beds, which represent over 50 plant families.

She’ll take close-up photos of the blossoms and foliage in the Rock Ledge Gardens, and of the choice dwarf bulbs that are tucked into every nook and cranny.

She’ll wonder how many of the primulas and saxifrages she’s seen in the Alpine House might do very well at her Own House.

The Primula and Saxifraga collections in full bloom, in the Alpine House. Image courtesy of Stonecrop Gardens.

She’ll pick the brains of the professional staff who are on site, and will then drive home, her car stuffed to nearly-exploding with the plants and shrubs that she’s purchased at Stonecrop’s Sales Benches. Leaving Stonecrop that afternoon without a single plant in my possession had required me to exercise extreme self-control: I was in the midst of a road-trip, and it was painful not to be able to adopt some of the exquisite specimen plants I’d admired. Although Stonecrop is clearly a Major Garden, it is also a place that’s straightforwardly about its PLANTS, and is thus UN-intimidating, even for Mere Gardening Mortals. After a couple of hours in the Garden-That-Cabot-and-Burgess-Built, the Visitor begins to imagine that she might indeed be able to combine plants in her own garden in the same charming ways as those of the Cold Spring Plant Masters.

With his gardening, Frank Cabot did great good in the world, and not just in his own back yards. He was Chairman of the New York Botanical Garden, and served as an advisor to both the Brooklyn Botanical Garden, and the Royal Botanical Gardens in Burlington, Ontario. But perhaps his most important accomplishment was that he made it possible for places as various as the inmates’ gardens at Alcatraz…

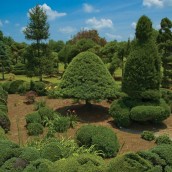

…or the Pearl Fryar Topiary Garden in South Carolina…

…or the cactus garden of Ruth Bancroft to be opened to the public.

All of these extraordinary places have been preserved with the help of The Garden Conservancy, which Frank Cabot founded in 1989, to save some of America’s most exceptional gardens for the education and enjoyment of the public. Find more out about The Garden Conservancy at: www.gardenconservancy.org

Directions to Stonecrop Gardens (and remember that both your vehicle and your shoes should have good traction): 5 miles east of the Village of Cold Spring, on Route 301, or 3.5 miles west of the Taconic Parkway, on Route 301.

Open from April through October, Monday through Saturday.

Admission fee: $5.00

Stonecrop Gardens

81 Stonecrop Lane

Cold Spring, New York 10516

Phone ( 845 ) 265-2000

www.stonecrop.org

Very tired after my day of garden-tromping, I drove south for another hour and a half, to Croton-on-Hudson, where I’d made reservations at the Alexander Hamilton House, a rambling Victorian bed-and-breakfast inn that overlooks the Hudson River. I’d booked two nights in their top-floor Bridal Chamber, which they describe as “the ultimate hideaway for a couples weekend or a diva’s escape.” And so this Diva bathed very well …

…and then slept very soundly.

The Bridal and/or Diva’s Chamber. Alexander Hamilton House. 49 Van Wyck Street, Croton on Hudson, New York. 10520

phone (914) 271-6737. www.alexanderhamiltonhouse.com

On the morning of June 7th, after a splendid breakfast cooked by my Innkeeper, I set out for Sleepy Hollow, where I had a 10AM reservation for a tour of Kykuit (pronounced to rhyme with “High-Cut”), the Rockefeller Family Estate. During my 30 minute, southward commute the rain intensified, and by the time I’d reached the Visitor Center at Philipsburg Manor, the deluge had become torrential.

Kykuit, the Rockefeller Family Estate, is in Sleepy Hollow, New York State, on the eastern banks of the Hudson River.

As a seasoned Garden-Explorer, I’m never thwarted by inclement weather. With my Wellington boots, hooded raincoat and sturdy umbrella, I felt equal to the day’s meteorological challenges. Tours of Kykuit are managed by the Historic Hudson Valley Organization. I’d booked their “Selected Highlights Tour,” a 2- hour-and-15-minute-long tour designed for visitors who want a cursory peek at the Main House, and an extensive ramble through the gardens. As I waited for more people to assemble, and for the shuttle bus that would take us uphill from Sleepy Hollow Village to Kykuit, I realized that no other souls were gathering. A distinguished-looking gentleman approached, and introduced himself as the Guide. Michael Onofrio assumed that, due to the appalling weather, and the complete absence of everyone else who’d reserved tickets for that morning, I’d want to reschedule. I laughed: “I’m used to bad weather! If you’re up for getting soaked, I certainly am.” Mr. Onofrio regarded me, and then he smiled. Low and behold, what I’d expected to be a group tour (and I only grudgingly tolerate being herded, during such outings) suddenly became a private tour. The morning’s biblically-intense rain had just ensured that I’d have the best possible look at Kykuit’s gardens…with one of Kykuit’s most-seasoned guides. With Bad Weather, came Good Luck.

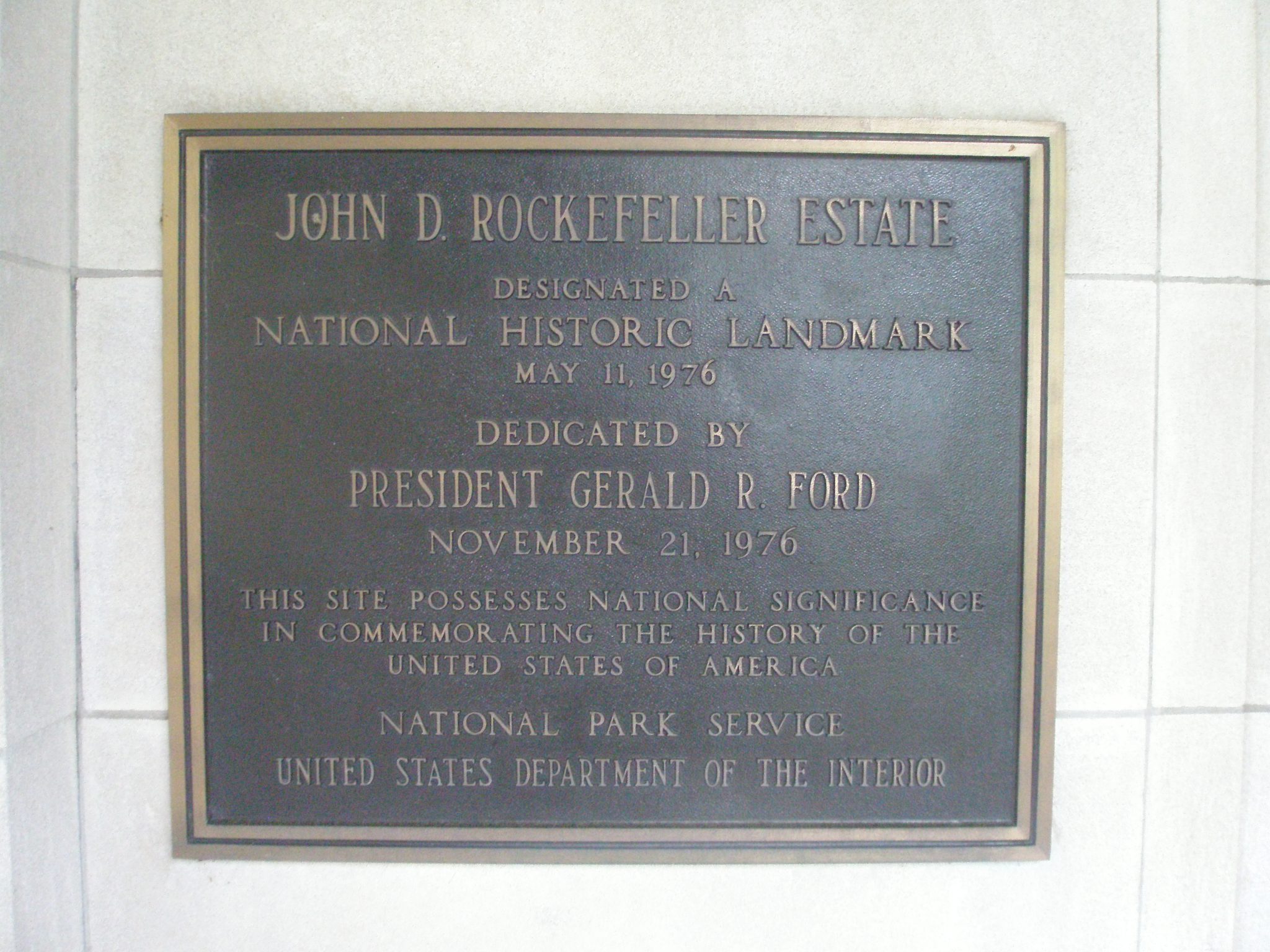

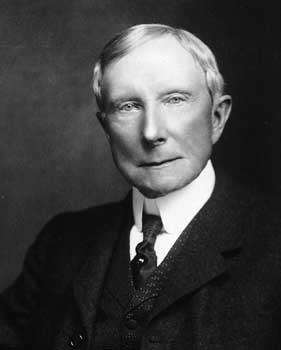

My purpose here is primarily to describe Kykuit’s gardens. I shall not recount the history of the ascent of Rockefeller family, which began with John D. Rockefeller’s founding of Standard Oil. In 1893, having become the wealthiest man in America, Rockefeller purchased land on the highest point of the Pocantico Hills and he named his property “Kykuit,” which, in Dutch, means “Look Out.” Rockefeller’s nearly 4000 acres overlooked the Tappan Zee, the widest point—at 3 miles—of the Hudson River.

JDR’s love was for the landscape, and throughout his long life (he lived to be 97, which suggests the benefits of being a teetotaler), he took great pleasure in designing scenic roads, fashioning lookouts, and transplanting trees in his not-so-little-Eden. Architecture was not one of Rockefeller’s interests: he wanted only a relatively modest home, one with a compact footprint. Delano and Aldrich (a distant family relative) were hired, and they designed a curious structure…a veritable architectural potpourri; one which combined rough-hewn fieldstone walls with delicately-detailed Colonial Revival porches, Tudor-beamed gables, and steeply-pitched, slate-beshingled French roofs. Yikes! Construction of the Main House at Kykuit, overseen by JDR’s son, John D. Rockefeller, Jr., became a misguided and chaotic affair.

In 1908, as soon as the six-year-long building process was completed, the house was found to be wanting, practically as well as stylistically. Fireplaces smoked, bedrooms were too small, and noise from the kitchen too great. The designer Ogden Codman Jr. (who you may recall from my article on The Mount was co-author, with Edith Wharton, of “The Decoration of Houses”), who’d already been commissioned to decorate the House’s interiors, was enlisted for a complete rethink and redesign of the Main House.

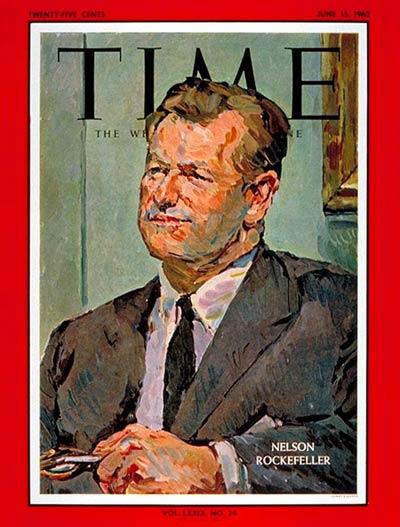

Ceilings were raised, and, working with the architect William Welles Bosworth, Codman designed entirely new facades which obliterated all traces of the original House. But, to my eyes, the most attractive features of the exterior of the House are the giant wisteria vines that climb over its walls and thus soften and mask the rather institutional look of the Codman/Bosworth “improvements.” Of the three generations of Rockefellers who lived at Kykuit, only Nelson, its final occupant, can be said to have possessed inherent, artistic vision.

It was Nelson’s inspired choice to plant those wisterias.

A Bird’s Eye view of Kykuit. Image courtesy of “Kykuit,” by Henry Joyce and the Historic Hudson Valley Press.

In the Above Photo: Foreground- The Grand Stairway, with its radiating zodiac mosaics. The Adam and Eve Fountain is at the base of the Stairway. At the top of the Stairway- the Oceanus Fountain. Approaching the House- the

Entrance Forecourt. To the West, the broad expanse of the Tappan Zee, the widest point of the Hudson River.

While the construction of the Main House at Kykuit was bumping along over its rocky course, the development of the landscape around the House was, in contrast, proceeding smoothly. In 1906, while JDR was abroad, Junior hired architect William Welles Bosworth to build extensive terraces and stairways and pavilions, as settings for gardens that would be planted on all sides of the House.

The gardens that we see today remain essentially unchanged from those that Bosworth designed, and are among the largest and best-maintained Beaux-Arts gardens in America. Bosworth’s other American masterpiece came later, in 1913, when he received the commission to design a new campus for the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, along the Charles River, in Cambridge.

By 1924, Bosworth had decamped to France, where he began to oversee the restorations of the Palace of Versailles, and the Chateau de Fontainebleau.

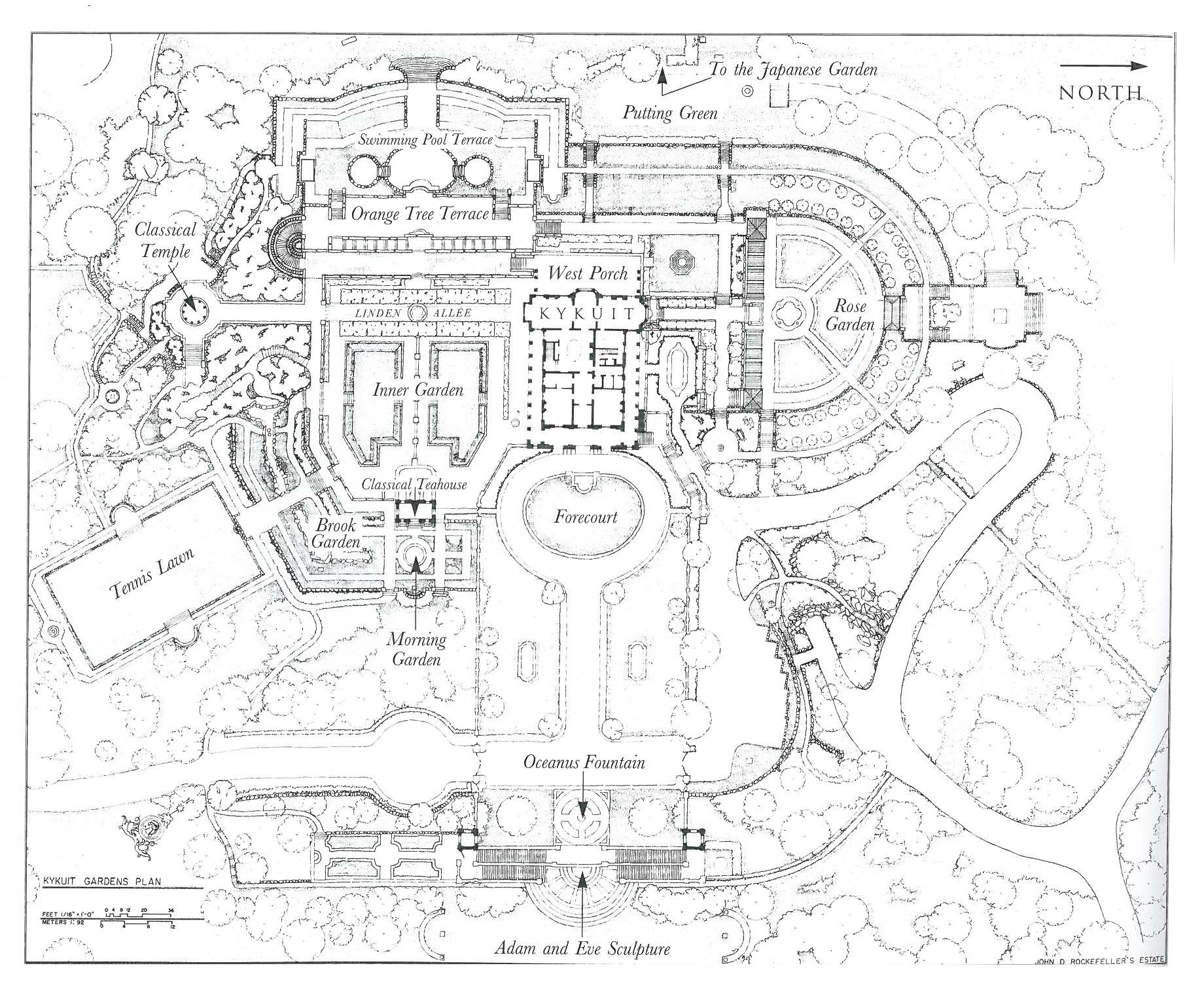

Map of the Gardens a Kykuit. Image courtesy of “The Rockefeller Family Home: Kykuit,” by Ann Rockefeller Roberts.

Michael Onofrio began my tour with a dash through the rain, along the length of the Entrance Forecourt.

Opposite the Front Entry Loggia are these flame-form favrille-glass, electrified torches, which are mounted on massive, cast-iron urns.

Pausing in the Loggia, I admired the first of many pieces from Nelson Rockefeller’s superb sculpture collection.

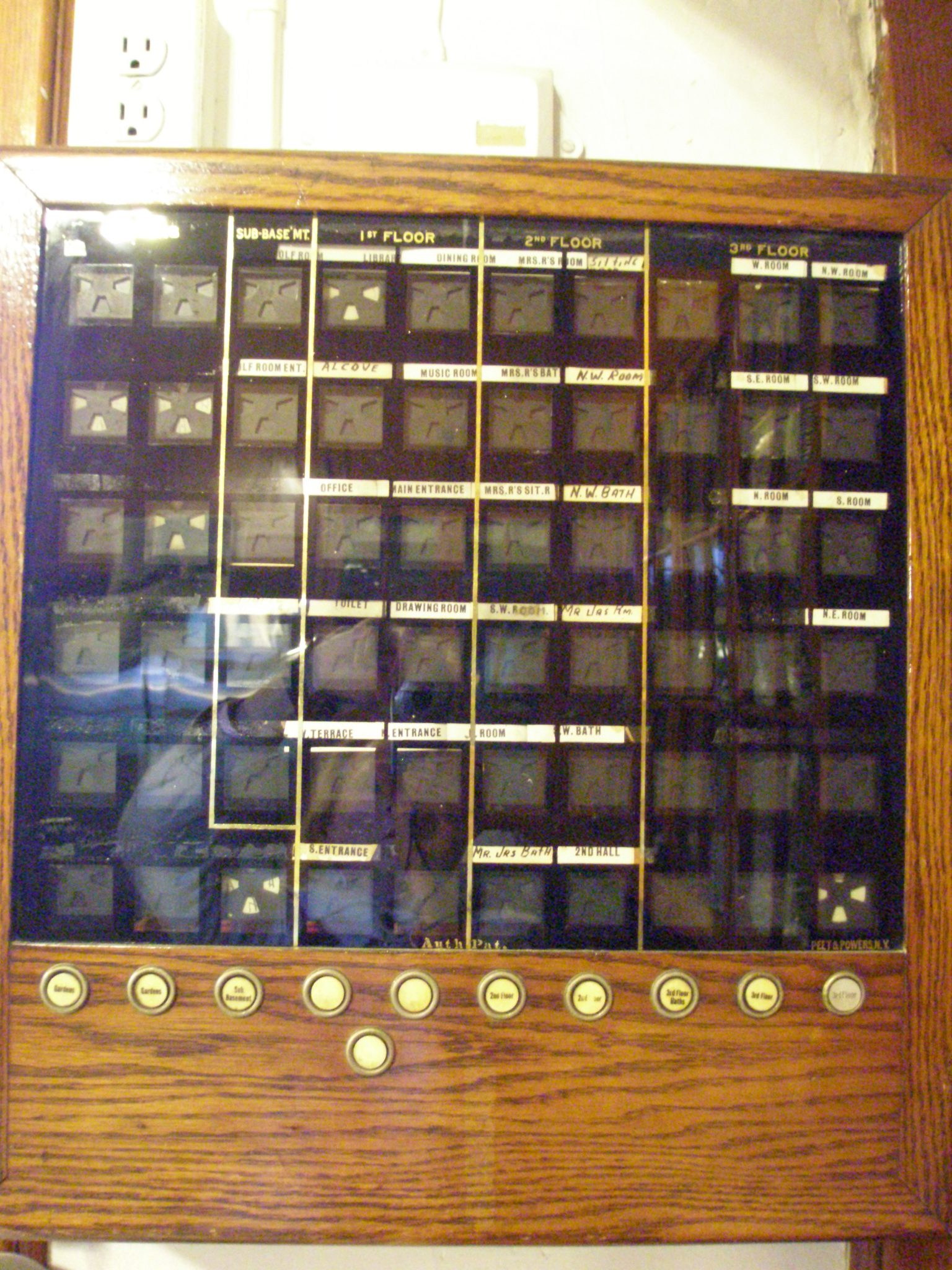

Once inside, where photos are prohibited, I nevertheless did some Very-Fast-and-Naughty-Picture-Taking (thus the bad lighting, and not-crisp focus).

Dining Room, with John Singer Sargent’s portrait of JDR, painted in 1917. Flanked by two massive Meissen birds (c.1734)

Library. Portrait of George Washington by Gilbert Stuart. I think the camel by the french doors is fabulous!

The Music Room. During the redesign of the interior of the House, Ogden Codman Jr. decided to knock a hole in the ceiling, so as to add an oculus and dome to this space. This posed serious structural challenges, as interior load-bearing beams had to be removed and then repositioned. All of the ornamental plasterwork in the house was designed by Codman.

Outside, on the West Porch, we began to get seriously wet. Here’s my photo-album of our soggy but very enjoyable garden explorations:

On the northeast corner of the West Porch: a view of the green roofs of the gazebos in the Rose Garden.

At the northwest corner of the West Porch: the view down over the Orange Tree Terrace, with the Swimming Pool Terrace below that. The winged, black sculpture is by Jacques Lipchitz: THE SONG OF THE VOWELS (1932)

Another view, when it’s not pouring, of the Orange Tree Terrace. Image courtesy of “The Rockefeller Family Home: Kykuit” by Ann Rockefeller Roberts.

A Moorish Pool and Fountain are set, mid-way along the Linden Allee. On the west terrace, the polished bronze of Peter Chinni’s NATURA EXTENSE (1965) shines, even on an overcast day.

The jewel in the Linden Allee Pool is a fanciful, gilt-bronze fountain by Francois-Michel-Louis Tonetti

View from the Linden Allee, back toward the french doors of the Library. From this vantage point, the Main House looks ungainly.

The Inner Garden is bisected by a Rill, which terminates at the Tea House. Aristide Maillol’s BATHER PUTTING UP HER HAIR (1930) is mounted, halfway along the Rill.

At the Tea House, a pool with more fountains by F.M.L.Tonetti. Mr. Onofrio’s umbrella is keeping him only partially dry.

Two’s a crowd in the Inner Garden: Gaston Lachaise’s STANDING WOMAN (1912-27), with her abstract counterpart

Just south of the Morning Garden is this 9-foot-tall display of Utter Goofiness:

Karel Appel’s MOUSE ON A TABLE (1971) !!!

Midway down the Grand Stairway is the Boxwood, or Italian Garden. This is the most untended of the gardens at Kykuit.

Each quadrant of the Italian Garden is watched over by a stone figure that represents one of the Seasons

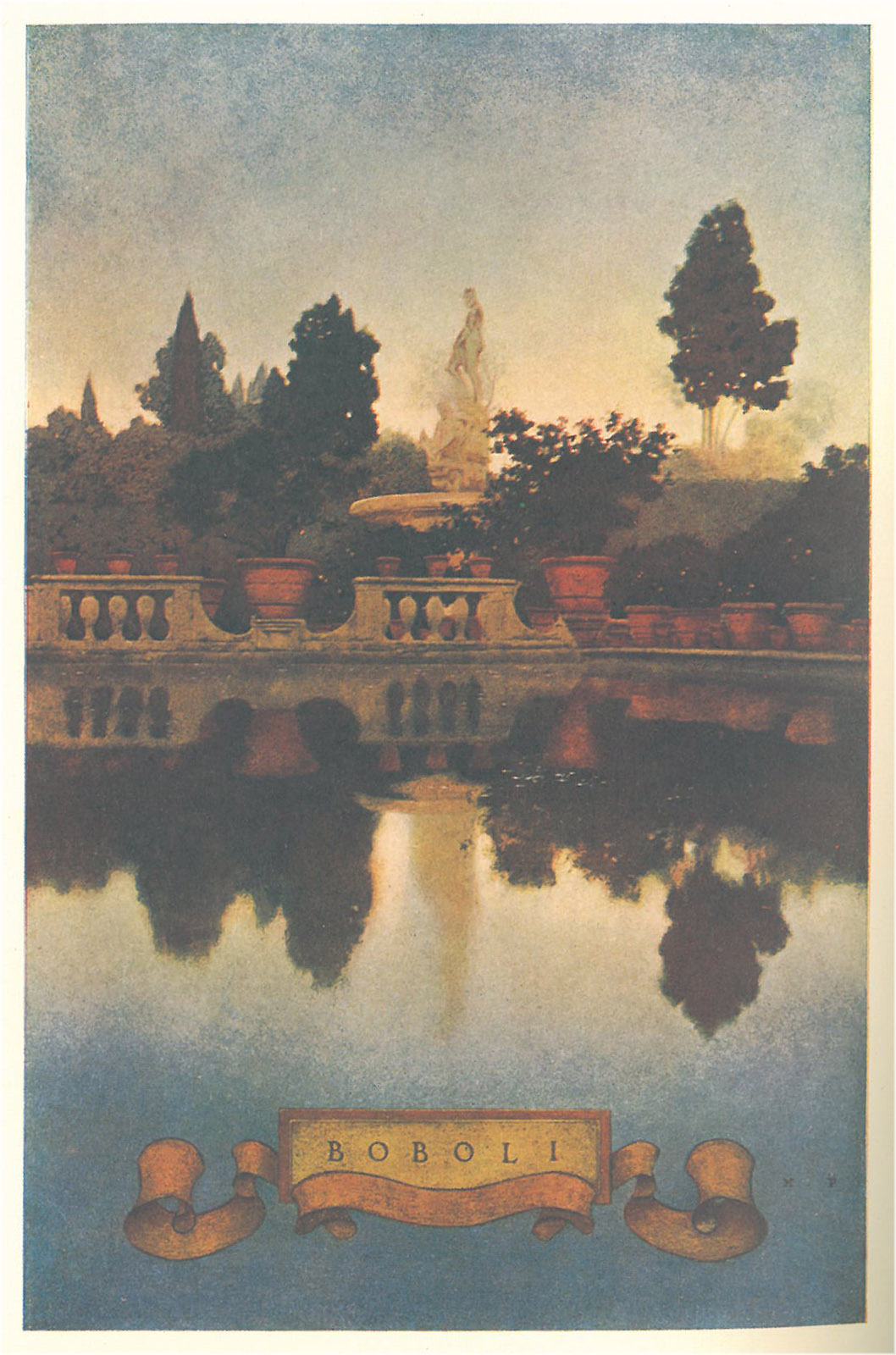

Climbing back up the Grand Stairway, we were confronted by the enormity of The Oceanus Fountain. Per Henry Joyce, “the Italian Renaissance prototype for the Kykuit Oceanus was a figure commissioned from the sculptor Giambologna about 1565 as the central feature of the Boboli Gardens at the Pitti Palace in Florence. Edith Wharton used illustrations of the fountain in her ‘Italian Villas and Their Gardens.’ The Kykuit Oceanus was made in Italy in 1913.”

Maxfield Parrish’s illustration of the Oceanus Fountain in the Boboli Gardens. This image taken from my own copy of Edith Wharton’s ITALIAN VILLAS AND THEIR GARDENS

My photo of the original Oceanus Fountain (seen looming in the background), taken in Florence’s Boboli Gardens during my visit on Sunday, Sept. 9, 2012.

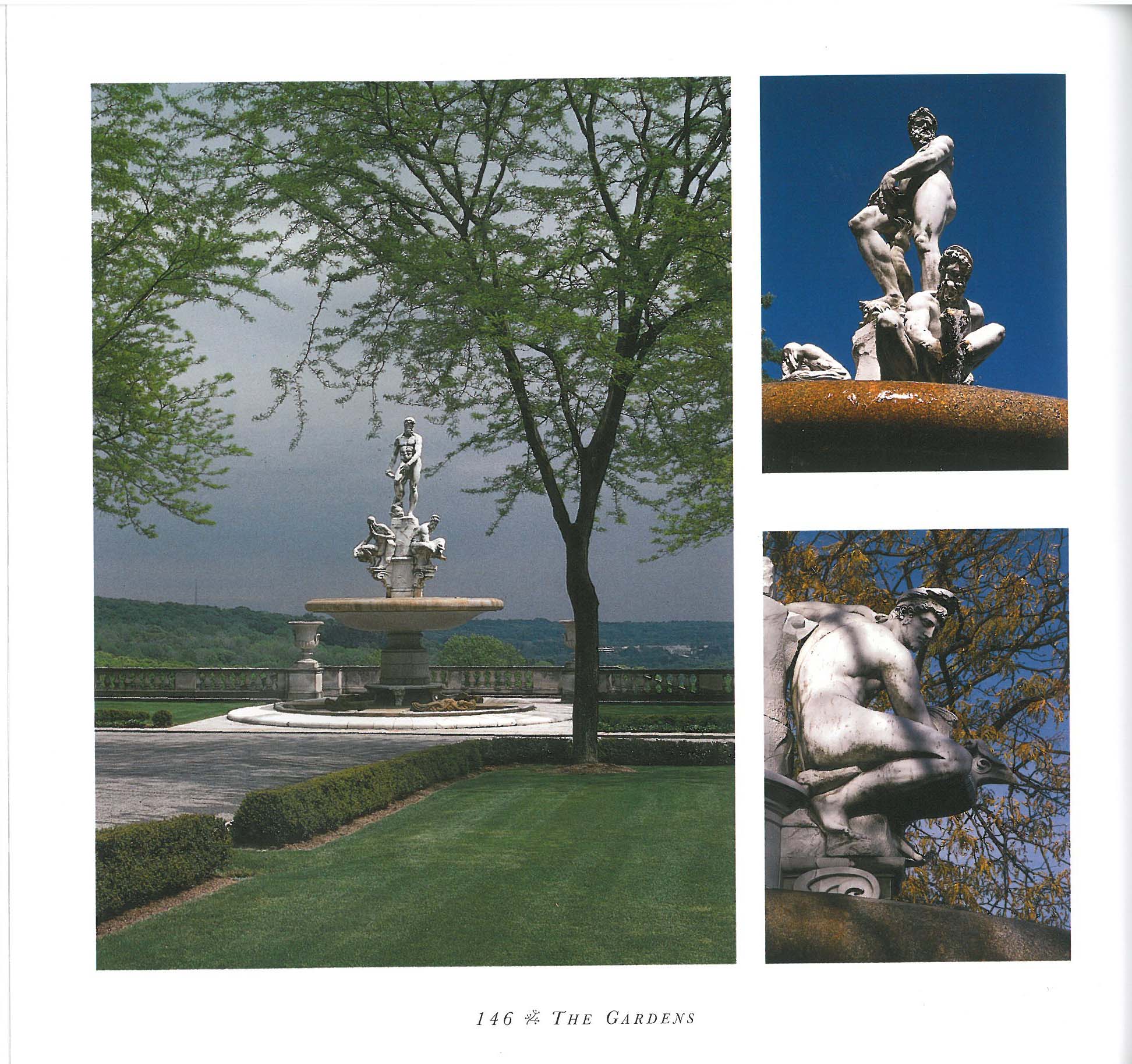

Kykuit’s Oceanus Fountain, in better weather. Image courtesy of “The Rockefeller Family Home: Kykuit,” by Ann Rockefeller Roberts

The Granite Bowl of the Oceanus Fountain is 20 feet in diameter and weighs 35 tons. It was produced in Maine, and shipped to Kykuit in 1914. I cannot imagine how difficult shipping this hunk of rock must have been.

A closer view of the Oceanus Fountain, showing two of the three river gods who surround the central figure of Oceanus

The Brook Garden. Rock was virtually all there was on this hill when the gardens began, so this brook had to be created. In the early Spring, pink blossoms adorn the weeping cherry trees.

..rain, Rain, RAIN…in the Brook Garden. Isamu Noguchi’s BLACK SUN (1960-63) is mounted on a slim, gray pedestal

Temple of Venus/Classical Temple. The Temple is placed within a small grove of American dogwood, and Japanese dogwood.

PAN, by Janet Scudder, is temporarily displaced from his niche on the path leading down to the Grotto that’s beneath the Temple of Venus

The Grotto, beneath the Temple of Venus, is a circular room, and features a Guastavino tile ceiling and Moravian tile floors. Eight massive sandstone masks crown columns around the perimeter. Emil Siebern, who worked at Kykuit from 1909 until 1914, decorated the space with classical sculptures. A Punch of Serious Drama comes from Giacomo Balla’s series of wooden sculptures, FUTURISTIC FLOWERS, which Nelson Rockefeller added in the early 1970’s. All in all, the Grotto is a magical (and relatively DRY, despite its name) space.

Icicle-form Lights of frosted glass, designed by William Bosworth and made by Tiffany. Guastavino’s arched, structural-tile ceiling may look familiar to you: he also did the ceilings in the concourses of Grand Central Station.

Michael Onofrio leads me away from the blessed dryness of the Grotto, and downhill towards the Swimming Pool Terrace

The Swimming Pool Terrace. That day, we were so rain-soaked that we might as well have been IN this pool.

A cast-stone mushroom table and chairs are under a pergola, on the level below the Swimming Pool Terrace

The statue at the western edge of the Putting Green: Gaston Lachaise’s MAN (1938)…on a day when it’s not raining. Image courtesy of “The Rockefeller Family Home: Kykuit,” by Ann Rockefeller Roberts

The black steel of Alexander Calder’s SPINY (1966) complements the wet bark of the trees along the Maple Walk.

Further along the Maple Walk is James Rosati’s LIPPINCOTT II (1965-69);

painted, cor-ten steel. And in the foreground, the snaking-line of BARBARA–HOMMAGE TO BARBARA REISE (1971-72), by Benni Efrat.

What James Rosati’s sculpture looks like on a sunny day…along with a spectacular view of the Hudson River. Image courtesy of “The Rockefeller Family Home: Kykuit,” by Anne Rockefeller Roberts.

Henry Moore’s KNIFE-EDGE, TWO PIECE, which Nelson Rockefeller commissioned, and then mounted on the grassy slopes below the Rose Garden

Splish-Splash! The Rose Garden’s fountain is a copy of yet another Medici fountain in Florence’s Boboli Gardens. The fountain is topped by a stone figure based upon a Donatello sculpture.

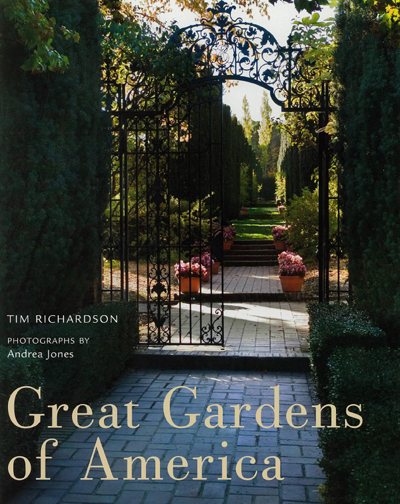

So….what to make of this splendor on the hillsides of the Hudson River? I’ve referred to many books about Kykuit, but Tim Richardson’s GREAT GARDENS OF AMERICA presents the best summary…and critique… of the Rockefeller family home. Here, some selections from Richardson’s book (which is much more than the coffee-table tome it seems at first glance to be).

“As a God-fearing Baptist, JDR preferred simplicity in all things, whereas his only son Junior had decidedly grander…tastes.”

“The overall effect of the [house] exterior is reminiscent of a pretentious provincial hotel.”

“The gardens, on the other hand, were a great success. They can be considered to have developed in three main phases from 1906 which mirror the periods JDR, Junior, and Junior’s son Nelson Rockefeller spent at Kykuit. They moved in, respectively, in 1908, 1937, and 1960.”

“In terms of landscape ideas, JDR was interested in the notion of the ‘picturesque’ landscape: flowing greensward, groves of copper beeches, stands of native elm and oak, and above all the fine vistas out across the Hudson River. His philosophy—perhaps inherited from his father, a successful farmer—was to massage the landscape a little to bring out its best qualities, but otherwise to leave it alone. This was certainly a cost-effective approach, too.”

“Junior, on the other hand, favored the Beaux Arts style which was fashionable in the decades around the turn of the twentieth century—an eclectic, eminently acquisitive mode of design which ‘quoted’ or ‘performed’ aspects of old French, Italian and English gardens while giving them a glamorous contemporary spin through the addition of elements such as modern figurative sculpture (very often nudes). The impetus in Beaux Arts design was for distinct themes in different parts of the garden, to engender a wide variety of garden experiences and moods. Anyone who commissioned something in the Beaux Arts style had to be content for their wealth to show.”

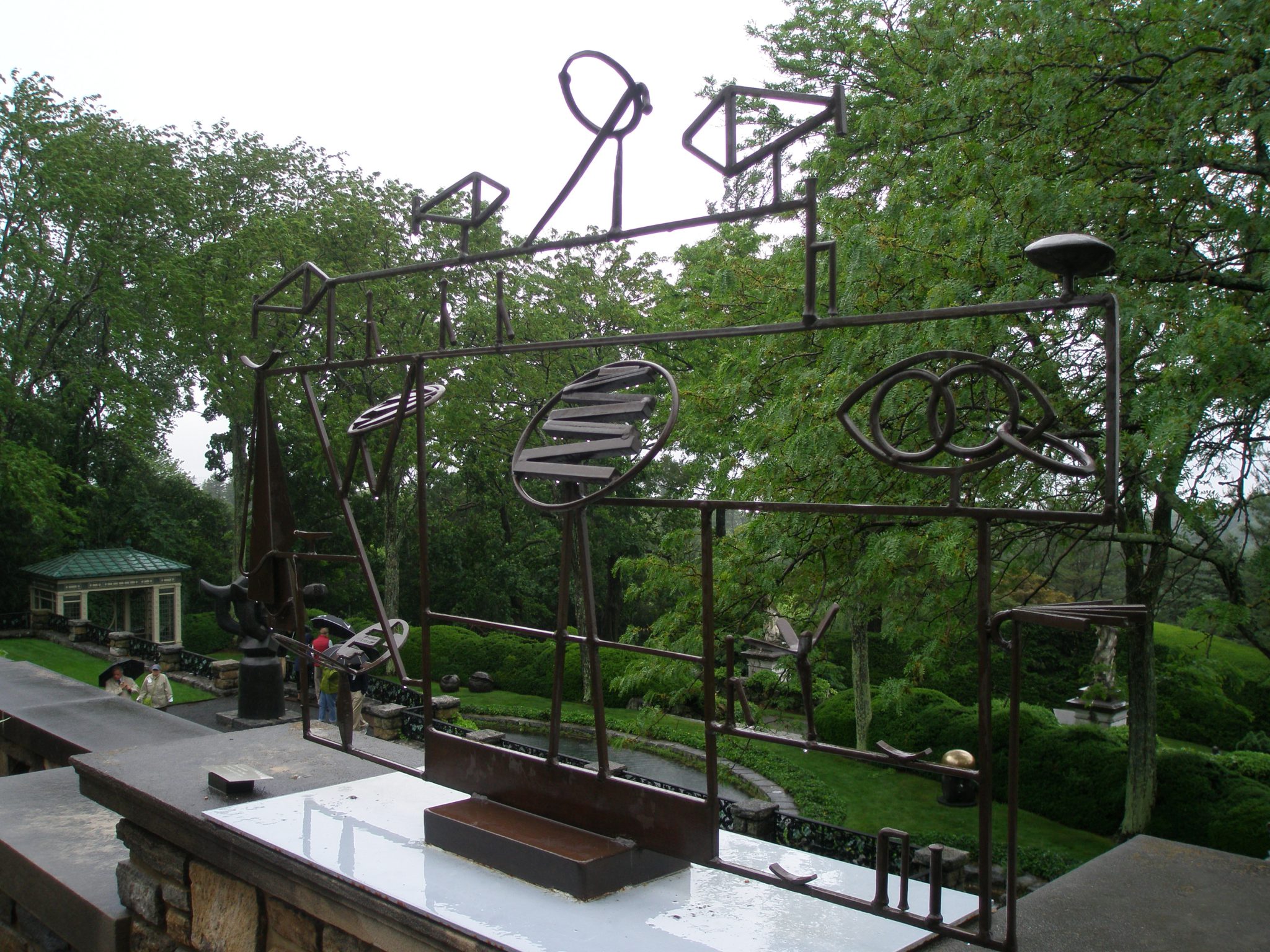

“The final phase occurred in the later twentieth century when Nelson Rockefeller added a great deal of sculpture to the landscape; interventions which perhaps constitute the most aesthetically successful period of the garden’s development and the aspect that qualifies Kykuit most convincingly as a ‘great garden.’ “

“It is in the lawns and parks to the north and north-east that the influence of Nelson Rockefeller can be felt most keenly, for here can be found some of the most arresting of the seventy or so pieces of sculpture placed throughout the garden. After Junior’s death in 1960 his second oldest son, Nelson, moved in, with the agreement of his siblings. Here was an art collector, politician (he was vice-president in the mid-seventies), and sometime president of the Museum of Modern Art in New York—a man of discernment. Nelson had realized that he would probably be the last of the Rockefellers who would be able to maintain Kykuit as a private home, and envisaged his tenure as an act of transition to the estate opening to the public. His main contribution to the garden remains the outdoor sculpture collection, work which ranges from the classicism of Maillol to the austere abstraction of Brancusi. It remains today one of the best and most ambitions examples of the integration of sculpture into an existing formal garden setting. Nelson Rockefeller integrated modern sculpture in some surprising places—such as the ammonite abstract sculpture TRIANGULAR SURFACE IN SPACE (1962) by Max Bill, now at the end of the pergola in the Rose Garden—but he invariably seems to have got it right. The modern sculpture collection adds an exciting contemporary zip to this classic Beaux Arts garden.”

On that stormy morning in June, Nelson Rockefeller’s sculptural additions to the garden seemed magical

Over 100 years ago, as architect William Welles Bosworth drafted his plans for the gardens which would embrace John D.Rockefeller’s country home, he looked back in time to Italy, to the villas and gardens of another impossibly wealthy and profoundly powerful family. As politicians, ruthless businessmen, and patrons of the arts, the Medici of Renaissance Florence were obvious models. (Note: For a refresher-course, read my article “Florence & Lucca: The villas, gardens & treasures of Tuscany,” which features several Medici gardens.) When I first arrived at Kykuit, I immediately recognized the Oceanus Fountain as a copy of the fountain in the Boboli Gardens, and my first thought was “How absurd! Why mimic Florence? Why not an Original, for this oh-so-American family?” But, forever-over-time, men of newly-acquired wealth and recently-born power have attempted to secure a footing in history for themselves, and for their descendants. As a rapid way of establishing gravitas and respectability, they’ve adopted the symbols and styles of their most-admired history-book predecessors. Such symbols, conspicuously displayed, serve as shorthand. The Oceanus Fountain devised by Junior’s architect announced: “We are mindful of what has passed before. We are cultured. We are rich as the Medici.” This is an assertion made mostly loudly by the Second-Generation; by the offspring of founders who were too busy empire-building to find time to also build palaces for themselves. By the time Junior’s son Nelson took over Kykuit, the Rockefellers’ places in American history were secure: symbol-borrowing time was done. From his secure perch, Nelson was able to approach the decoration of Kykuit’s gardens idiosyncratically, and he adorned his home in a way that harmonized with his particular, restless aesthetic sense. There are sections of the gardens where an over-abundance of art detracts from each, individual piece: along the wall of the Inner Garden, within the Grotto, and on the West and Orange Tree Terraces too many sculptures, in too many styles, vie for breathing room. But even in these areas of Too-Muchness, there’s a vestige of the exuberance of the Collector: Nelson Rockefeller’s sheer excitement about choosing, and then positioning these creations is still palpable. Visit Kyuit…and pray that it rains. From the day’s inclemency I gained the highest luxury; that of utter privacy as I sloshed and splashed and explored the homestead of this imposing American family. Of course, it remains to be seen if, 600 years from now, the Rockefellers are remembered with an awe equal to that with which we of today remember the Medici! But this is just one more of the millions of things we’ll never know….

Kykuit: The Rockefeller Estate

Open from early May through late September

Tours assemble at the Visitor Center of Philipsburg Manor

381 North Broadway

Sleepy Hollow, New York 10591

Phone ( 914 ) 631-8200

www.hudsonvalley.org

Coming Soon: I’ll begin my Five-Part Series on the Gardens and Estates of Kent, England.

The circular, late 14th century tower at Scotney Castle, near Royal Tunbridge Wells, in Kent, England. I took this photo on August 6, 2013.”

Copyright 2014. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express &

written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

4 Responses to Hudson River Valley Gardens–Part Two: Stonecrop, & Kykuit