Penshurst Place and Gardens. Tonbridge, Kent, England. Photo taken on August 5, 2013. The Gardens at Penshurst are among Britain’s oldest privately owned gardens. The Sidney family has been in continuous occupation of the house (the main portions dating from 1341) for the last 462 years. In 1554, the most illustrious Sidney of them all was born there: Sir Philip, who became a poet, soldier and courtier

February 2014. Although not by design, some days of my Kent-Garden-Touring also became days of Finding-the-Haunts-of-Famous-Authors. Kent has always been a fertile place: its beautiful landscapes have nurtured the growing of plants, and the assembling of words, in equal measure. Although I won’t officially get to Jane Austen until my fifth in this series of Kent travel diaries, I kept one particular Austen-ian sentence in mind, throughout my entire week in “The Garden of England.” On a Wednesday in 1798 (December 19th, to be exact), Jane Austen penned yet another long and delightfully bitchy letter to her beloved sister Cassandra.Jane’s temporary address was at Godmersham Park—Faversham, in Kent— where she and her parents were enjoying an extended visit with her brother, Edward Knight. [About the difference in their surnames: Edward was Jane’s third eldest brother. In Edward’s teens, he hit the proverbial jackpot when his childless relatives, the very wealthy Catherine and Thomas Knight, took a shine to him and decided to adopt, thus making him their only heir. Ka-chiiinnggg…at least ONE of the Austens needed no longer to squeeze his coins till they bled!]

Godmersham Park, in Kent. Home of Jane Austen’s brother, Edward

Knight. This building is not open to the public.

Austen’s missive had begun slyly : “My dear Cassandra. Your letter came quite as soon as I expected, and so your letters always do, because I have made it a rule not to expect them till they come….”After several pages of reporting about bonnet trimmings (a black feather was to be replaced by a silk poppy), the weather (Jane had enjoyed a long walk on a crisply cold day), a horse-riding accident (not hers, thank goodness) a forthcoming Ball (“There will be nobody worth dancing with.”), and what sounds very much like Mrs. Austen’s hypochondria (Mother’s unsettled “Bowels, an Asthma,a Dropsy, Water in her Chest, and a Liver Disorder”…all of which smack of the complaints of Mrs. Bennet, in “Pride and Prejudice”), and then of getting down to Really Serious Business—which was Jane’s exhaustive analysis of the financial status of everyone she’d recently met—Austen’s tone relaxed, with these words: “KENT IS THE ONLY PLACE FOR HAPPINESS.” To the traveler who is immersed in the sheer beauty of Kent, to be Un-Happy there would indeed take some doing. But of course, Austen immediately tempered her glowing words: “Everybody is rich there.” Since we know that Jane Austen’s lack of financial resources weighed heavily upon her–for her entire life– this qualification speaks volumes about how difficult it must have been for her to have always been dependent upon the hospitality of wealthy hosts for the Kentish sojourns that she so loved. I’ll have more to say about Jane in forthcoming articles, when Amanda and I stroll through the gardens at Goodnestone Park (which was the home of Edward Knight’s in-laws, the Bridges family… who often entertained Jane Austen), and later on, when Anne and David Guy and I spend a day in Lyme Regis (where Austen often vacationed, and where she set a pivotal scene of PERSUASION).

Goodnestone Park, in Canterbury, Kent.

In 1791, Elizabeth, the third daughter of Sir Brook Bridges married Jane Austen’s brother, Edward Knight. Jane Austen was frequently entertained at Goodnestone Park by the Bridges family. I visited the beautiful gardens surrounding the Manor House on August 8, 2013.

So, to further demonstrate why Jane Austen Had It Right—that Kent IS indeed a place for happiness—please continue to travel with me and Amanda Hutchinson (Blue Badge Guide, par excellence www.southeasttourguides.co.uk ) and Steve Parry (Chauffeur, par excellence www.snccars.co.uk ). On that Monday, August 5, 2013, the works of Kent’s gardeners and writers seemed especially and closely bound.

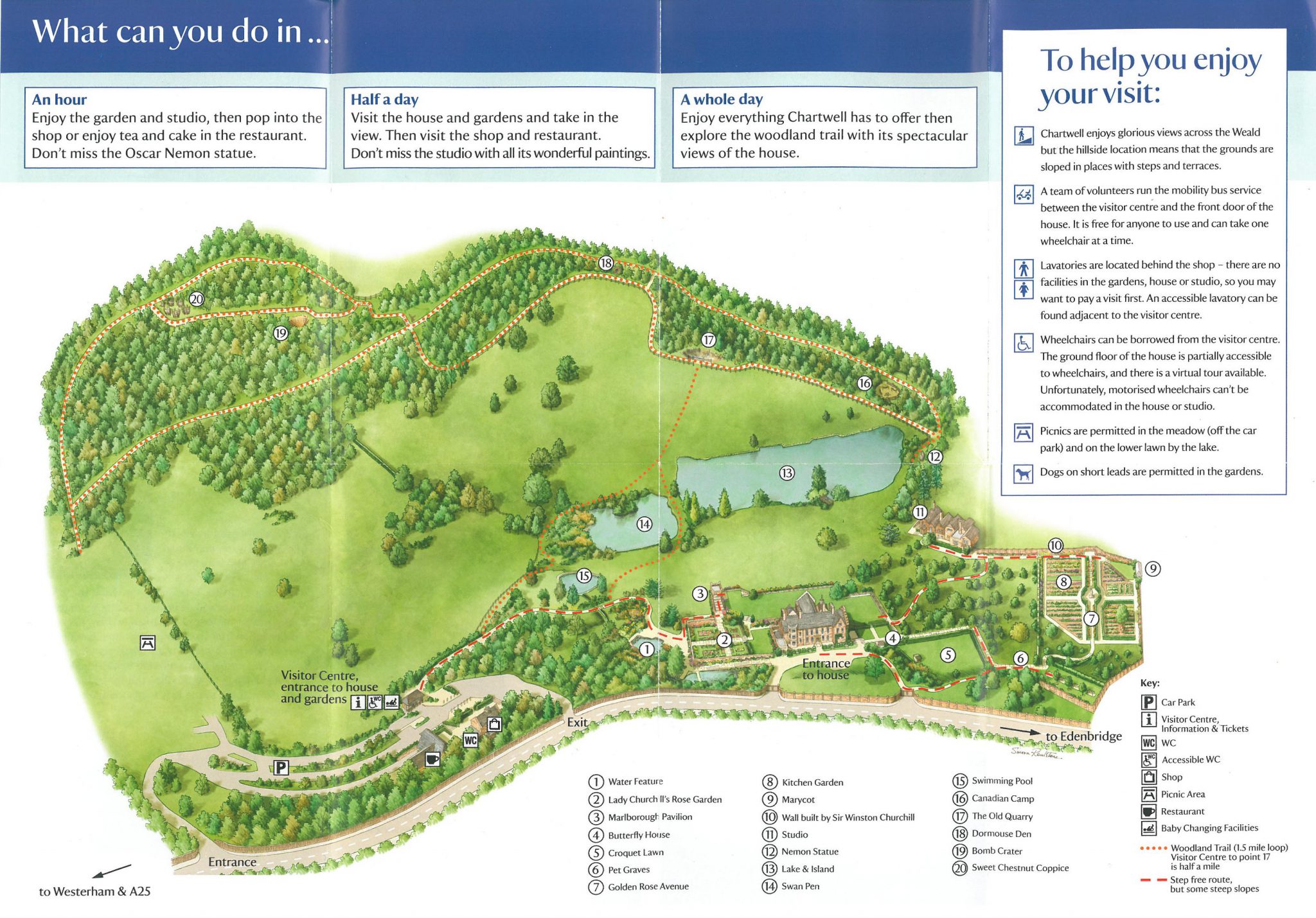

Destination #1: Chartwell, the Family home of Winston Churchill Mapleton Road, Westerham, Kent TN16 1PS Open from early March through October, 11AM to 5PM Telephone: 01732-868381 Website: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/chartwell/

Chartwell, where Winston and Clementine Churchill lived for over 40 years. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

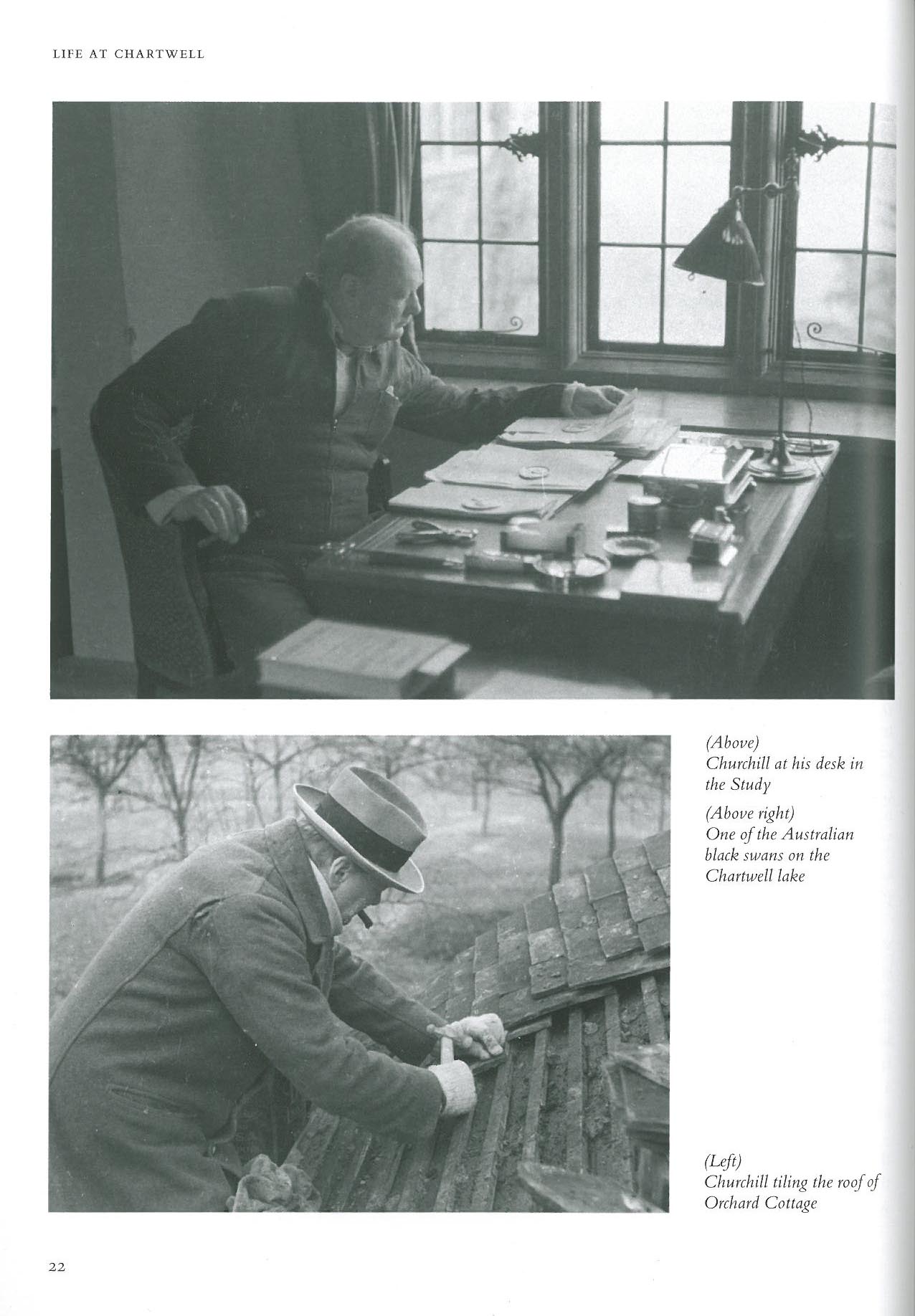

Our day’s tour began with an Historical Bang: promptly at 10AM, we arrived at Chartwell. HOW on Earth does one summarize the life of a polymath like Winston Churchill? A hybrid-child—the product of a wealthy and footloose American mother and an unhealthy English father who was descended from the Dukes of Marlborough—Churchill was born prematurely: two months before his time. But Winston ultimately became a man exactly FOR his times. As Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, from 1940 to 1945, he was Britain’s inspiring wartime leader; the orator who stiffened the resolve of his countrymen through the sheer power of his words. However, the prime times of every man must always pass: during his second term as Prime Minister, from 1951 to 1955, Churchill unwillingly presided over what he called the “dismemberment” of the British Empire, as the impossibility of continuing the colonial rule of far-off lands was made violently apparent. During his long life (born—1874, died—1965) Churchill was a neglected child, and an indifferent student…and then a challenging husband, and a doting father. He was a wild-eyed war correspondent, a fortunate soldier, and a dominant and wily politician…even though he never escaped the jaws of his “black dog”: the serious depressions that tormented him. As an historian, and author of countless speeches and articles, he wrote at least 10 million words, some of which caused him to be awarded the Nobel Prize in Literature. Winston decompressed from his frantically active life by gardening and bricklaying…and by painting and drinking. When the fame of a man has become as formidable as Churchill’s, we either assume that we know all there IS to know…or we shrug and say that pulling aside the trappings of fame to find the truth about a person is impossible. But, to make a few steps beyond hagiography, there’s nothing so helpful as taking a peek at a public figure’s home. We speculate: without Chartwell’s modestly-appointed rooms, without the orderly gardens, without the mundane concerns of managing the care of his dairy herd, along with Chartwell’s mother sow and her piglets, might Winston Churchill have been less able to temper his wild swings between brilliance and despair? I think the answer is clear: without his retreat in the Kentish hills, Churchill would certainly have been far less functional—and thus less useful— when England’s extreme circumstances demanded his very special skills.

Winston Churchill in 1939. In the background, renovations are underway. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

Amanda and I had an hour to spare until the House opened, and so began our amble through Chartwell’s extensive gardens. Guidebook in hand, I paused to read its Introduction, written by Mary Soames, the youngest of the four Churchill children. As they did for her father, words also sprang gracefully from Mary’s pen, as she described this House which her father had bought, over the objections of her long-suffering mother! “Chartwell was Winston and Clementine Churchill’s home for 40 years. My father bought it in September 1922, in the week that I, their last child, was born, and until I was 17 it was to be my whole world.” “While Winston and his children loved Chartwell unconditionally, Clementine from the first had serious practical reservations about the whole project. Her prudent Scottish side judged the renovations (involving largely rebuilding the house), and the subsequent cost of running the whole property, would place a near intolerable strain on the Churchills’ somewhat fragile financial raft. She was to be proved right, and over the years her pleasure in the place was seldom unalloyed by anxiety. Clementine, however, never stinted thought or effort in making Chartwell a delightful, comfortable home for her family. My mother imprinted the stamp of her lovely, and always unaffected, taste on both house and garden.” “Winston had been captivated by Chartwell from the moment he set eyes on the valley, protected by the sheltering beech woods (sadly devastated by the 1987 gales), and by the house set on the hillside, commanding sweeping views over the Weald of Kent. The Chart Well, which rises at the top of the property, nourished the existing lake, and Winston saw at once the possibilities it provided for yet another lake, dams, swimming pools and water gardens. In all of these projects over the ensuing years, he himself would play the role of creator and artisan.” “The walls enclosing the vegetable garden (built very largely with his own hands), and the dear little cottage he made for me, bear witness to his skill and assiduity as a brick layer. Chartwell also provided countless scenes—still lifes and interiors—for Winston’s brush. The Studio at the bottom of the orchard was the place (apart from his Study) where he spent the greater number of ‘indoor’ hours.”

“But if Chartwell was his playground, it was also his ‘factory.’ Throughout the twenties and thirties, in or out of office, Winston Churchill was immersed in politics. The lights in the beamed Study upstairs gleamed late through the night and into the small hours, as, padding up and down the long room, he dictated for hours on end to his secretary the ceaseless stream of speeches and newspaper articles through which he waged his political campaigns. Likewise there flowed from his pen the continuous procession of books which kept his family nourished, and Chartwell from foundering.”

On the path from the Visitor Centre to the House, we passed a herd of dairy cows. Visitors enter the property at its northern end.

Once through the Gate and into Lady Churchill’s Rose Garden, this was our first view of the House. Four standard wisterias grow where the garden paths meet.

Mixed Borders of plants with pastel blossoms hug the inner perimeters of Lady Churchill’s Rose Garden.

The Marlborough Pavilion was built in the mid 1920s, and decorated in 1949 by Churchill’s nephew, John Spencer Churchill. The theme of the decoration is Churchill’s greatest ancestor, John Churchill, First Duke of Marlborough.

The frieze around the ceiling evokes the Marlborough wars. One panel shows the defense of the village of Blenheim; the climactic moment of the Duke’s most famous victory. The Duke’s grand palace in Woodstock, Oxfordshire, is named after this battle. Winston Churchill was born at Blenheim Palace…but not by plan. As mentioned, his arrival came a bit ahead of schedule.

This is just one wing of the enormous Blenheim Palace, in Oxfordshire. As you can see, it’s a BIT grander place than Chartwell is. Winston was born here in 1874. I took this picture on Sept. 24, 2008…which seems like a million years ago.

We’re back now to the more modest charms of Chartwell. A terra cotta medallion of the First Duke of Marlborough adorns an inner wall of the Marlborough Pavilion.

On the north wall of the Pavilion are the First Duke’s coat of arms, and the family’s Spanish motto: “Fiel Pero Desdichado”…”Faithful but Unfortunate.” Seeing how things turned out for Marlborough, that motto was IN-Accurate!

Just south of the Pergola and Marlborough Pavilion is the Terrace Lawn. From this lawn one can enjoy the long view south, over the Weald of Kent. Churchill bought the House for this View.

Below the Terrace Lawn, acres of grass extend down to two lakes and a swan pen. Further afield are broad meadows, and forests of Chestnut trees.

Another lake view. Although the lakes appear natural, they are almost entirely Churchill’s creations. By damming a stream, Winston transformed what had been a silted-up bog into two lakes.

The view from the Terrace Lawn, up toward the back of the House. After Churchill bought Chartwell, his architect Philip Tilden built a new wing, which extended out into the garden. The 3 stories of this addition contained a Dining Room on the garden-level basement, a Drawing Room on the ground floor, and a barrel-vaulted bedroom for Clementine on the first floor. Ever-dramatic, Churchill called his addition “my promontory.”

A terrace at the juncture of the old and new portions of the House. The arched window is one of the many windows that extend around 3 sides of the Dining Room.

View of the rear of the House from the southernmost point on the Terrace Lawn. Clementine planted a Magnolia grandiflora, which has reached a substantial height, against the trellis-work attached to the House.

The Butterfly House Walk begins at the southwest corner of the Terrace Lawn, and is lined on the right by a high yew hedge. To the left, the land slopes away to the Orchard. Clementine planted these borders with buddleias to lure the butterflies that Churchill loved to see in the garden. Worried about the decline in Britain’s native species, Winston called in a butterfly breeding expert for advice on converting the summer-house at the end of this walk into a place to incubate butterfly larvae.

At the end of the Butterfly House Walk is the Croquet Lawn. During the 1930s Clementine’s tennis court occupied this space….she was the athlete in the family. After WWII, it became the Croquet Lawn.

Clementine Churchill. Portrait done in 1946, by Douglas Chandor. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

Buttressed brick walls enclose the Orchard. A row of Kentish-tile-hung cottages is behind the wall. Clementine referred to these as her ” village.”

Amanda and I looked down over the precisely-groomed beech hedges that enclose the Golden Rose Avenue. The Avenue was created in 1958 as a golden wedding present to the Churchills from their children.

We’re inside the Golden Rose Avenue, which runs east-west in the garden. The beds contain yellow and gold flowering roses, planted on each side in two parallel rows. Lambs ears and lavender billow out across the paving stones.

Midway along the Golden Rose Avenue is a circular terrace with a sundial. Below the sundial is buried a pet dove that Clementine brought home from a cruise to Bali in 1935. The dove survived for 2 or 3 years at Chartwell.

Chartwell’s gardens are full of personal touches.

This wall in the Kitchen Garden was built by Winston, who could lay down 90 bricks an hour. In 1928 he took out a card as an adult apprentice in the Amalgamated Union of Building Trade Workers. Oh…THAT Winston!

From 1915, painting was Churchill’s principal form of relaxation from the stresses of politics. The Studio was built in the 1930s, and became his favorite hideaway.

As 11AM opening time approached, we walked around to the Lawn by the front entry of the House. At the core of the present Chartwell are the remains of a substantial 16th century house. Henry VIII is said to have slept here in a room (now gone), while courting Anne Boleyn at Hever Castle. The unusually tall, thin and narrow building was probably designed as a hunting lodge. Over the centuries it grew, in higgledy-piggledy fashion.

The architect Philip Tilden, who oversaw all of Churchill’s renovations and additions at Chartwell, found this elegant 18th century wooden doorcase at an antique shop in London.

Chartwell: Plans of the House. Visitors are not allowed to take photos of the interiors, which are decorated in a comfy and low-keyed manner. After Winston’s death in 1965, Clementine gave the House to The National Trust, with the furnishings of its principal rooms virtually intact. She also bequeathed a collection of about 60 of Winston’s own paintings to the Trust. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

Churchill’s first floor Study is the most important room at Chartwell, and is one of the few recognizable, surviving parts of the original house. At first, Churchill slept here in a four-poster bed, but during the 1930s, he used an adjacent room as his bedroom. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

Lady Churchill’s Bedroom is on the top floor of the 3-storey addition, on the south side of the House. The barrel-vaulted ceiling is painted the same duck egg blue color that coats the walls. Churchill called this room his wife’s “magnificent aerial bower.” Image courtesy of The National Trust.

I adored the basement-level Dining Room, which has windows on three sides. The sea-grass carpet is woven specially for this space and the room is suffused with the fresh aroma of that grass. This rug is regularly replaced, so as to maintain the clean smell that Winston enjoyed. The vivid glazed chintz covering the chairs is the same pattern–“Arum Lily”–that has always decorated the room.

Our house-inspection ended, we exited through the basement level kitchen, onto this south-facing terrace.

As we concluded our visit, we passed once again through Lady Churchill’s Rose Garden. Our last look at Chartwell was as beautiful as the first had been.

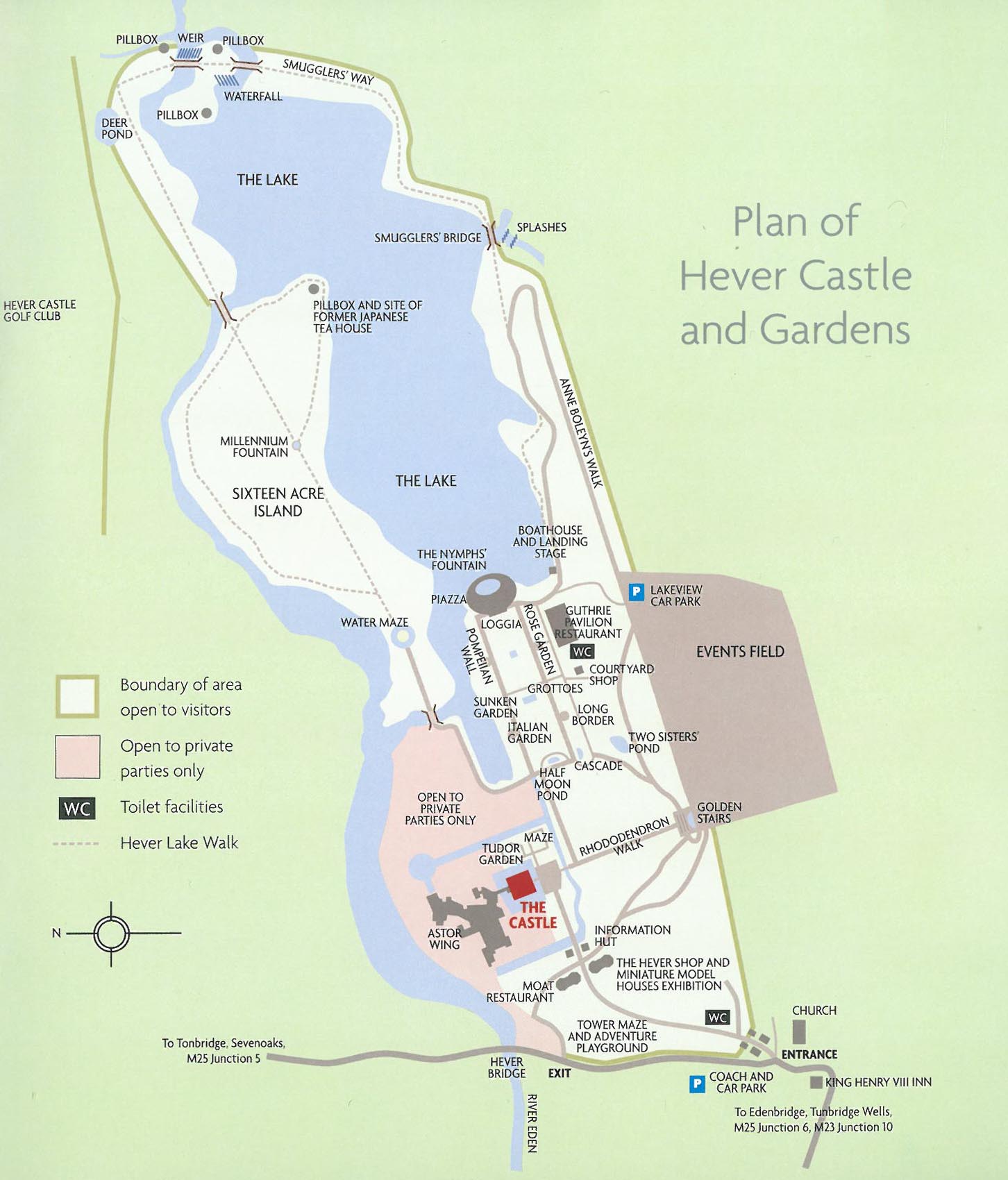

Destination #2: Hever Castle & Gardens Hever, Near Edenbridge, Kent TN8 7NG Open from April through October, Daily, 10:30AM—5PM Telephone: 01732-8652244 Website: www.hevercastle.co.uk

Hever Castle, Anne Boleyn’s childhood home. A castle has occupied this site since 1270. The current Castle, which is surrounded by a moat, dates from the 15th century. Image courtesy of Hever Castle.

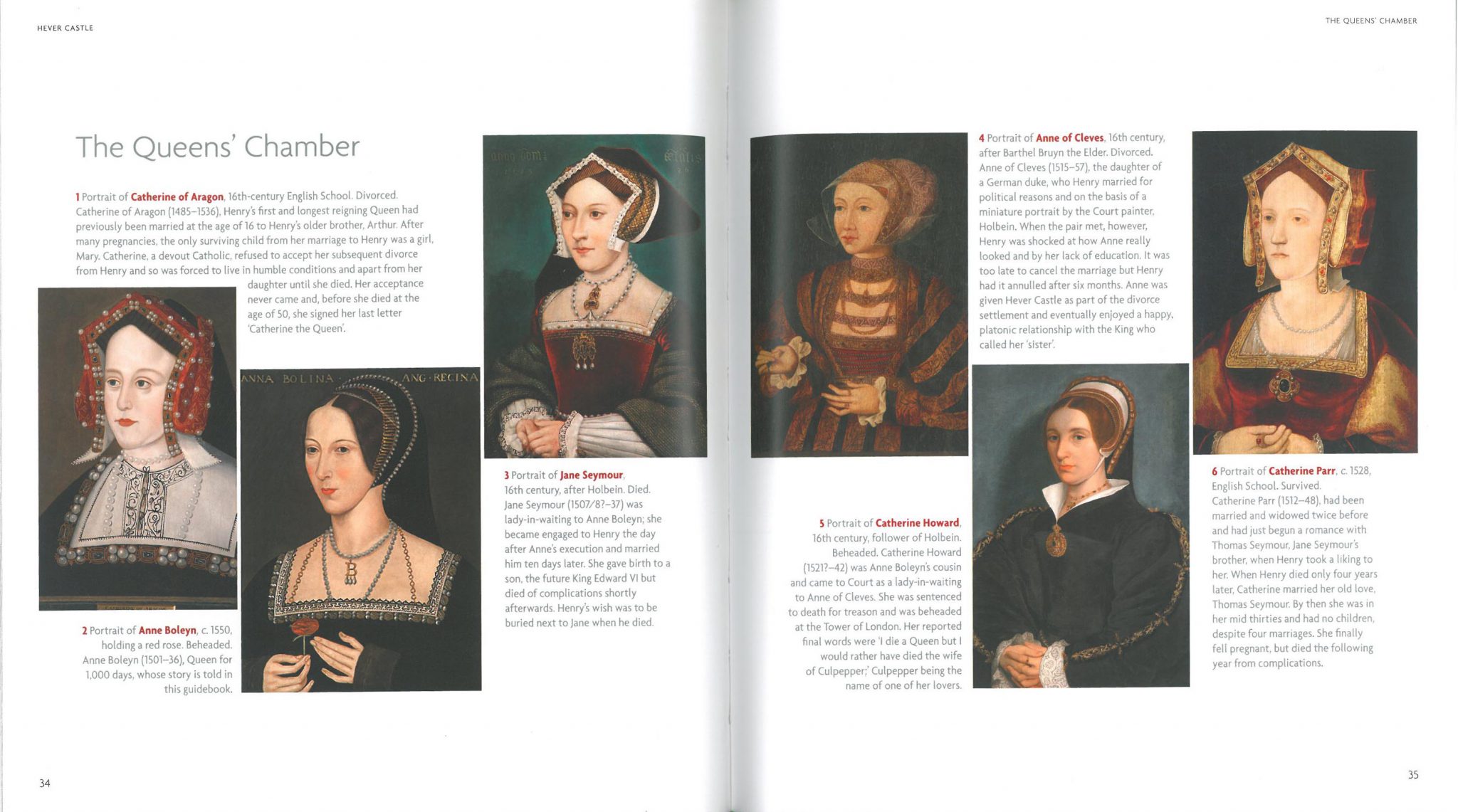

Very likely following the same route as did King Henry VIII in 1525, when he rode from Chart Well to Hever Castle, Amanda and Steve and I then made the short journey to the moated dwelling that, during the 15th and 16th centuries, was home to the Bullens (known today as the “Boleyns”), one of the most powerful families in England. I cannot say the words “Anne Boleyn” without feeling a tinge of sadness…which is then followed by a simmer of outrage. For those who know the rhyme, “Divorced, Beheaded, Died. Divorced, Beheaded, Survived,” which helps history buffs remember the fates of Henry VIII’s six wives in their proper order, Anne Boleyn has the gruesome distinction of being the first “Beheaded.”

In his incessant and desperate quest for a male heir, Henry consumed women. No lady who fell under Henry’s hungry gaze fared well. The Hever Castle guidebook summarizes Anne Boleyn’s short-and-UN-sweet life this way: “In 1509, eight years after Anne Boleyn’s birth, Henry Tudor, then aged 18, succeeded to the throne of England a Henry VIII. He secretly married Catherine of Aragon, the 24-year-old widow of his elder brother, Arthur. Their marriage produced only one child out of eight pregnancies: a daughter, who became the future Queen Mary I.” “Anne Bullen spent much of her time as a child at Court, pushed forward by her ambitious father, Thomas. At the age of 13 she joined the household of Margaret of Austria in the Netherlands before becoming maid-of-honour to Henry’s sister Mary Tudor, who was to marry King Louis XII. Anne then became maid-of-honour to Queen Claude of France and stayed with her for nearly seven years. It was in France that Anne Bullen became known as Anne Boleyn. There were no set spellings in Tudor times as few people could read or white, so Anne chose to sign herself Boleyn, probably for the more sophisticated sounding French pronunciation.” “In 1522 Anne returned to England, where her sister, Mary, had become mistress to Henry VIII. Anne was by now a sophisticated young woman she found Hever quite dull in comparison. She was soon appointed lady-in-waiting to Queen Catherine, during which time she fell in love with the young Lord Henry Percy.This did not please the King, who had other plans, so she was banished to Hever; lovesick and furious.” “By 1525 King Henry was desperate for a male heir. Bored with his former mistress, Mary, he fixed his attentions on 25-year-old Anne and began to make frequent visits to Hever.” “Anne was striking to look at: intelligent, sophisticated and fashionable. By that time, Henry was 32 years old, over 6 feet tall, handsome, extremely athletic and well educated.”

Henry VIII in his Rampant Prime. Painting by Hans Eworth, after the famous portrait by Hans Holbein. Image courtesy of Chatsworth House.

“Despite a relentless courtship, Anne refused to become his mistress, saying ‘Your wife I cannot be, because you have a Queen already. Your mistress I will not be,’ thus forcing Henry to take action in order to be able to marry her. As a Catholic, Henry had to seek the approval of the Pope to divorce Catherine. Henry was furious when the Roman Catholic Church refused his petition; thwarting his plans. He then announced that his marriage had not been legal in the first place, due to Catherine’s previous marriage to Henry’s brother, Arthur. Declaring himself head of the Church of England, he married Anne in secret and pronounced his marriage to Catherine null and void. Many years of religious upheaval followed his dramatic actions; monasteries were dissolved, English Catholics rose up against the King and prominent men refused to take an oath of allegiance to Henry. Thus, the Reformation was set in motion—all for the love of Anne Boleyn of Hever.” “When the pregnant Anne was crowned Queen in London in June 1533, there were few cheers. Her child, a girl, was born in September and named Elizabeth. Anne went on to miscarry in 1534 and again in 1536 and Henry began to believe that this marriage was cursed and Anne’s lady-in-waiting, Jane Seymour, was moved into new quarters at Henry’s palace. By May 1536 Anne was a prisoner in the Tower of London, accused of incest with her brother, adultery with several gentlemen, witchcraft and treason. She was found guilty and sentenced to death by burning; but her sentence was commuted to beheading.”

Anne Boleyn, before Henry VIII’s false charges (I mean, really: incest?? witchcraft???…Anne was too smart to have indulged in either!) deprived her of her head. Image courtesy of Hever Castle.

“Although Anne only reigned for 1000 days and failed to provide Henry with a male heir, it was her daughter, Elizabeth I, who became one of the longest-reigning monarchs that England has ever had.”

Queen Elizabeth I, daughter of Anne Boleyn and Henry VIII, was England’s last Tudor monarch. She ruled from 1558–1603, and her reign is generally considered one of the most glorious in English history.

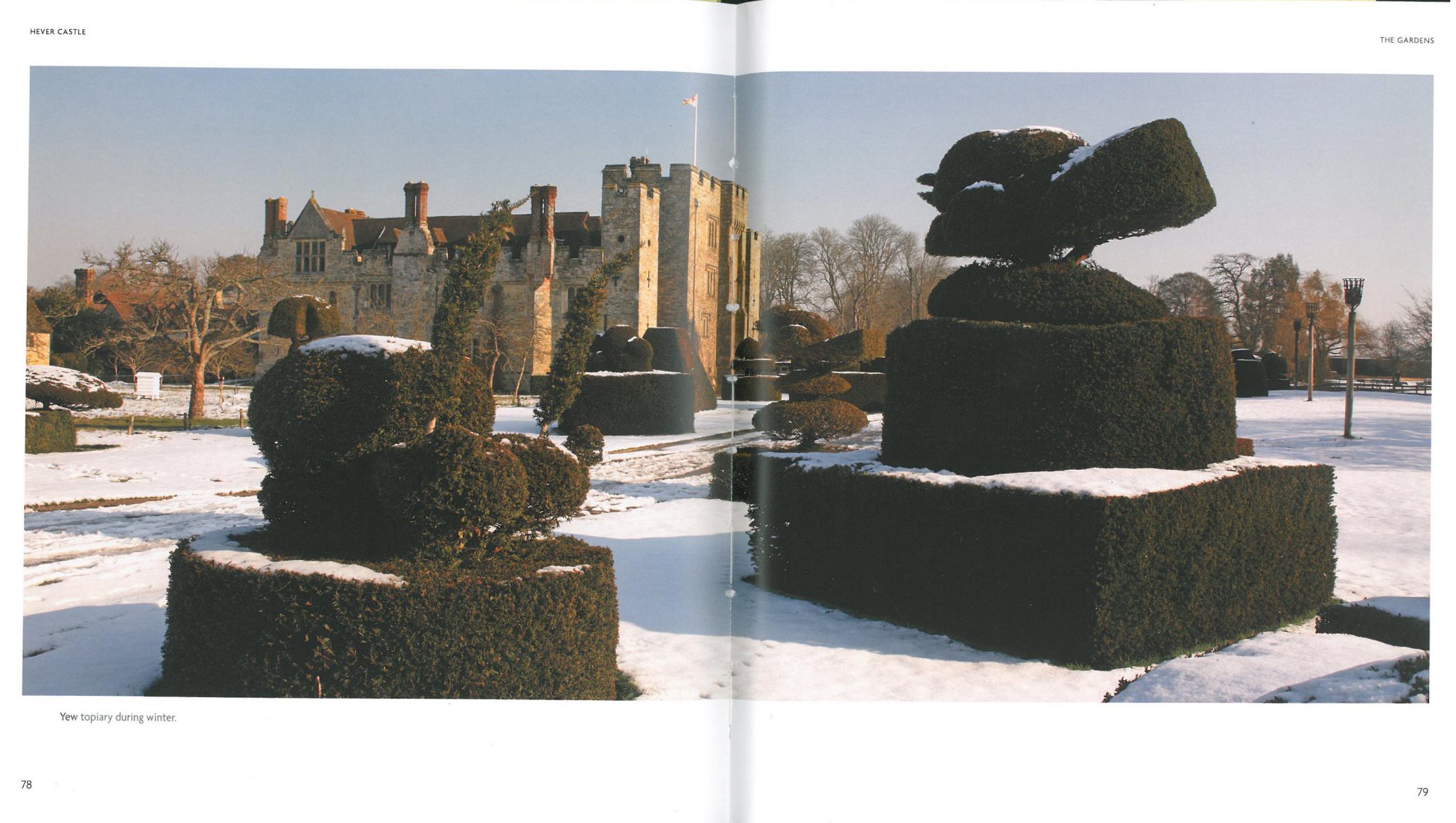

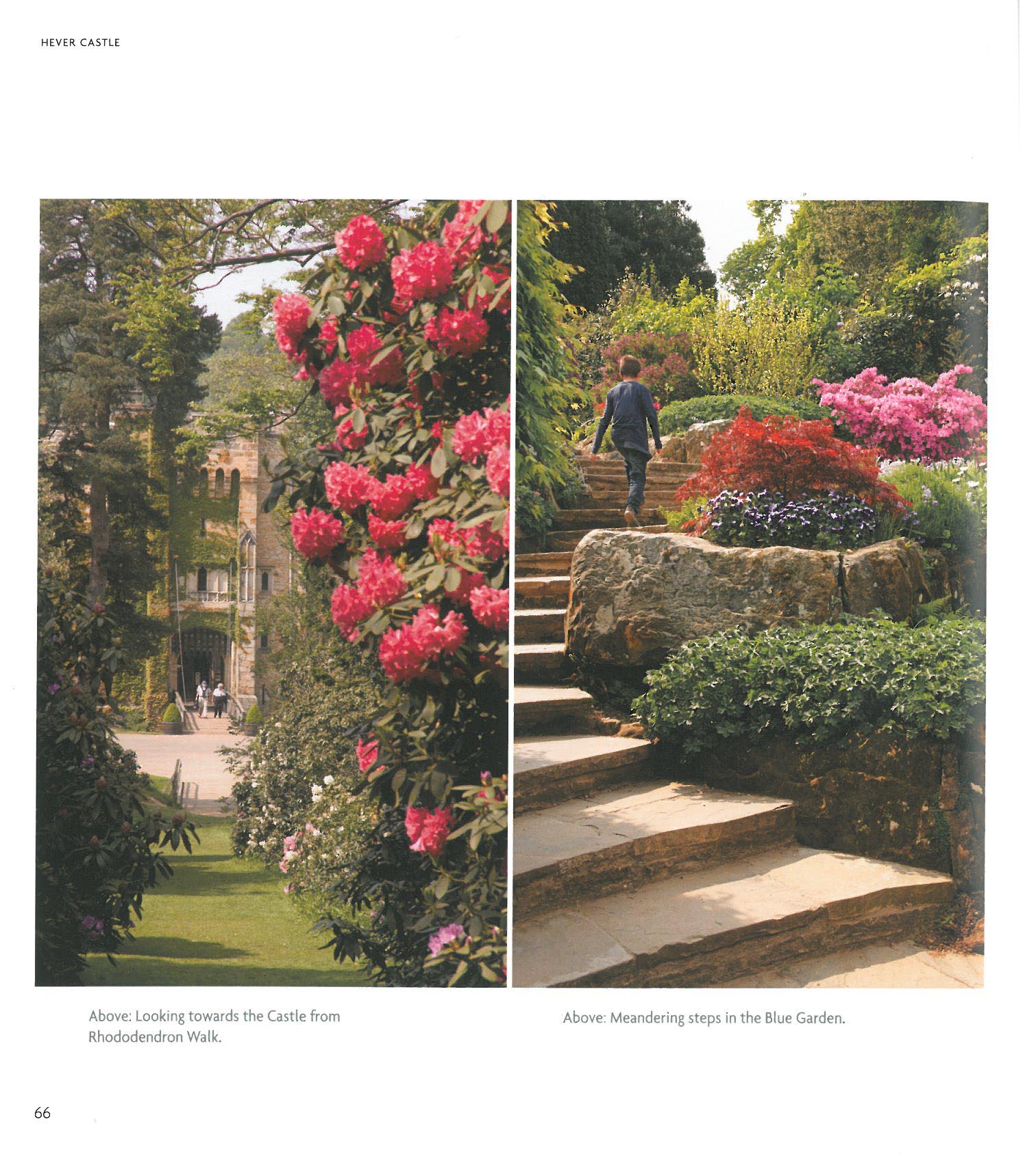

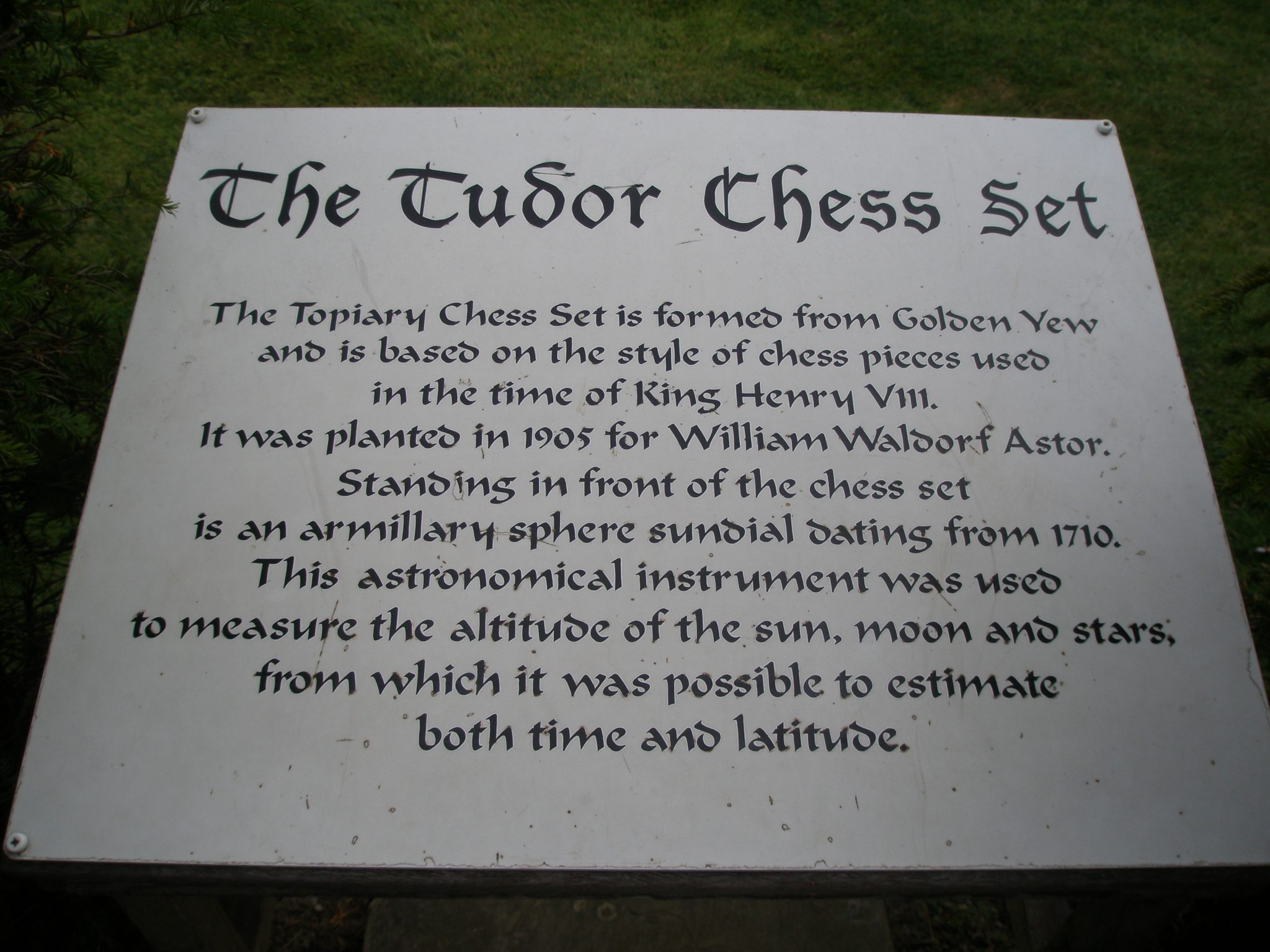

No wonder Elizabeth I chose to remain unmarried for all of her 45 years as Queen; she’d learned, in the most brutal manner possible, how deleterious marriage could be to a woman’s well-being. Despite the specter of uxoricide that hangs over Hever Castle, it’s a historically significant spot that all Kent-explorers should visit. Before we embarked on our Castle tour, Amanda and I wandered through the extensive gardens, most of which were constructed in the early 1900s, when the American-born William Waldorf Astor (only son of the financier and philanthropist John Jacob Astor III) purchased Hever, and began pouring vast sums of money into the property, which had fallen into decline.

Not content with simply renovating the Castle, Astor attacked his garden-building chores with almost fanatical zeal. 800 men were given the task of digging the 38 acre lake that today’s Visitors to Hever Castle pass as they enter the grounds. 125 acres of classical gardens and natural-looking landscapes were built and planted. A rambling, ersatz Tudor Village, which adjoins the Castle and is incongruously named the “Tudor Wing” was constructed. All of Astor’s additions are so massively over-the-top that they threaten to swallow the Castle, which seems refreshingly tasteful and delicately scaled in comparison. The skies darkened, and the air became dense with moisture. Despite heavy rain in the offing, we stepped lively and began our explorations of William Waldorf Astor’s Gardens.

Landing Stage at the east end of the Lake. One of the rowboats is christened “Anne of Cleves,” to honor Henry VIII’s fourth wife. This Anne can perhaps be considered to be the most fortunate of Henry’s spouses; their union was annulled after 6 months because Henry found her, his “Flanders Mare,” unappealing. As part of the divorce settlement, she was given Hever Castle. Eventually, Anne of Cleves and Henry enjoyed a platonic friendship: he called her “sister.”

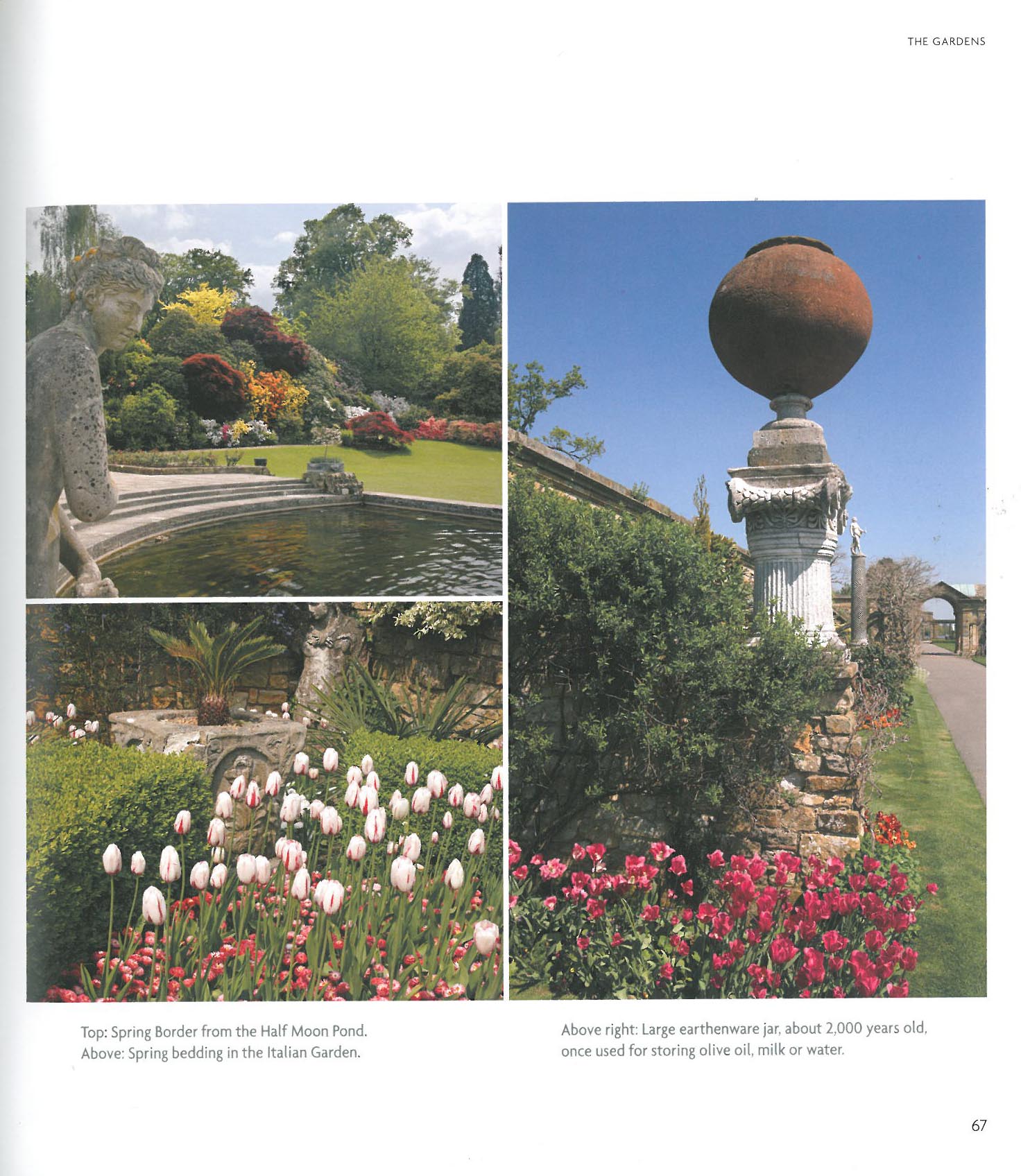

We knew that, when it finally came, the rain would be heavy. Here’s a view of the Loggia, from the Lakeside end of the Italian Garden. William Waldorf Astor decorated this Garden with hundreds of ancient statues and urns and miscellaneous ornaments.

The Italian Gardens have a collection of enormous earthenware jars…which are my favorites among all the garden decorations.

The north, inner edge of the Italian Garden is called The Pompeiian Wall. These borders are decorated with garden antiques and bright plantings of annuals.

A canal separates the Italian Garden area from the Sixteen Acre Island, where private events are held in elaborate tents.

Finished with our inspections of Astor’s Italian and Rose Gardens, we approached Hever Castle itself. In its 1270 incarnation, Hever was a simple motte-and-bailey castle; a structure built primarily to protect its occupants. A stone keep would have been perched on a raised earthwork (the motte), surrounded by an enclosed courtyard (the bailey), and finally encircled by a ditch.

During the 15th and 16th centuries, the Bullens transformed Hever Castle into the refined Tudor dwelling that we see today.

Finally, we prepared to enter the Castle itself:

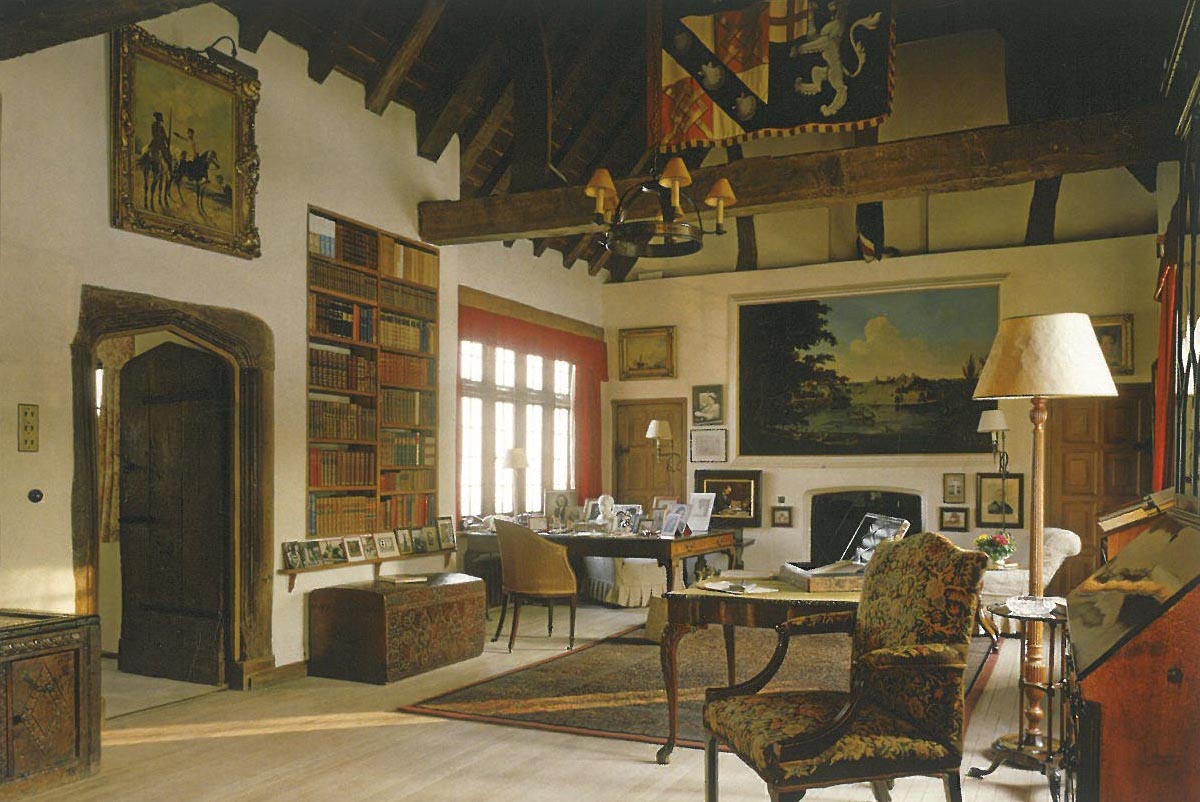

The Entrance Hall to Hever Castle. This was added to the Tudor manor house in 1506 by Thomas Bullen, Anne’s father. Thomas, First Earl of Wiltshire, and later Earl of Ormond, was a gifted linguist and a trusted diplomat. The furnishings that today adorn the space include a 1480 choir stall (on the right), and a 1565 Italian refectory table (on the left). Image courtesy of Hever Castle.

The Inner Hall. The splendor of the reception room that greets visitors to Hever today is a complete contrast to its original use in Tudor times, when this was the Great Kitchen, complete with a large fireplace for cooking and a well for water. Between 1903 and 1908, William Waldorf Astor redid the space with Italian walnut paneling and columns. Image courtesy of Hever Castle.

The Staircase Gallery is the smaller of two galleries in the Castle and was created in 1506 by Thomas Bullen over the Entrance Hall to give access between the two wings of the house and his newly-built Long Gallery. Image courtesy of Hever Castle.

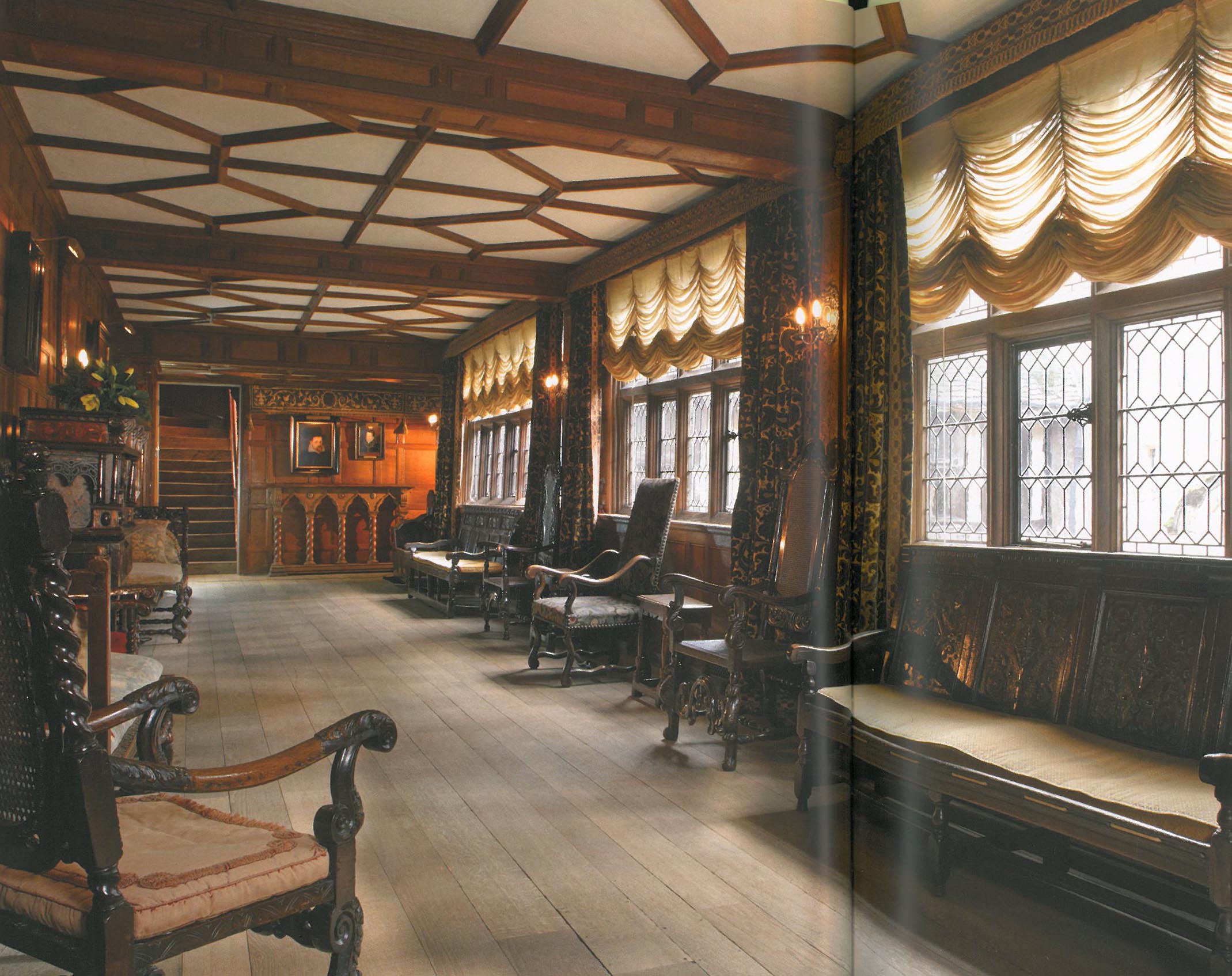

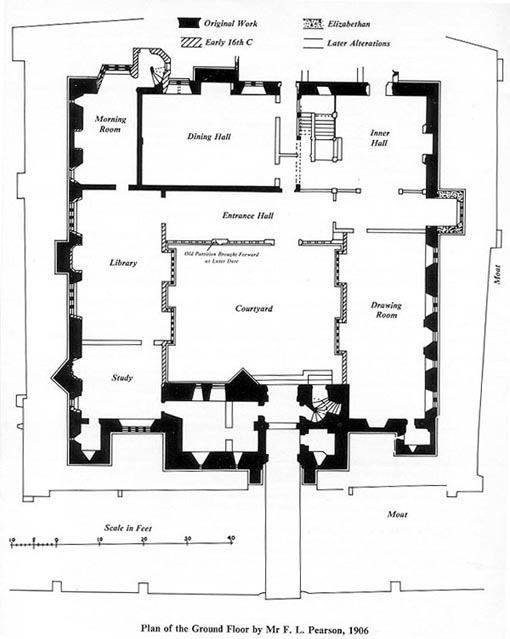

The Long Gallery is more than 98 feet long and runs the entire width of the building. This was added by Thomas Bullen in 1506, and was used for entertaining, displaying art, and taking exercise during inclement weather. The paneling is Elizabethan, and the ceiling is a 16th century style reproduction made for Astor. Tradition says that

Henry VIII held Court in the alcove at the far end of the Long Gallery when he visited Hever Castle. Image courtesy of Hever Castle.

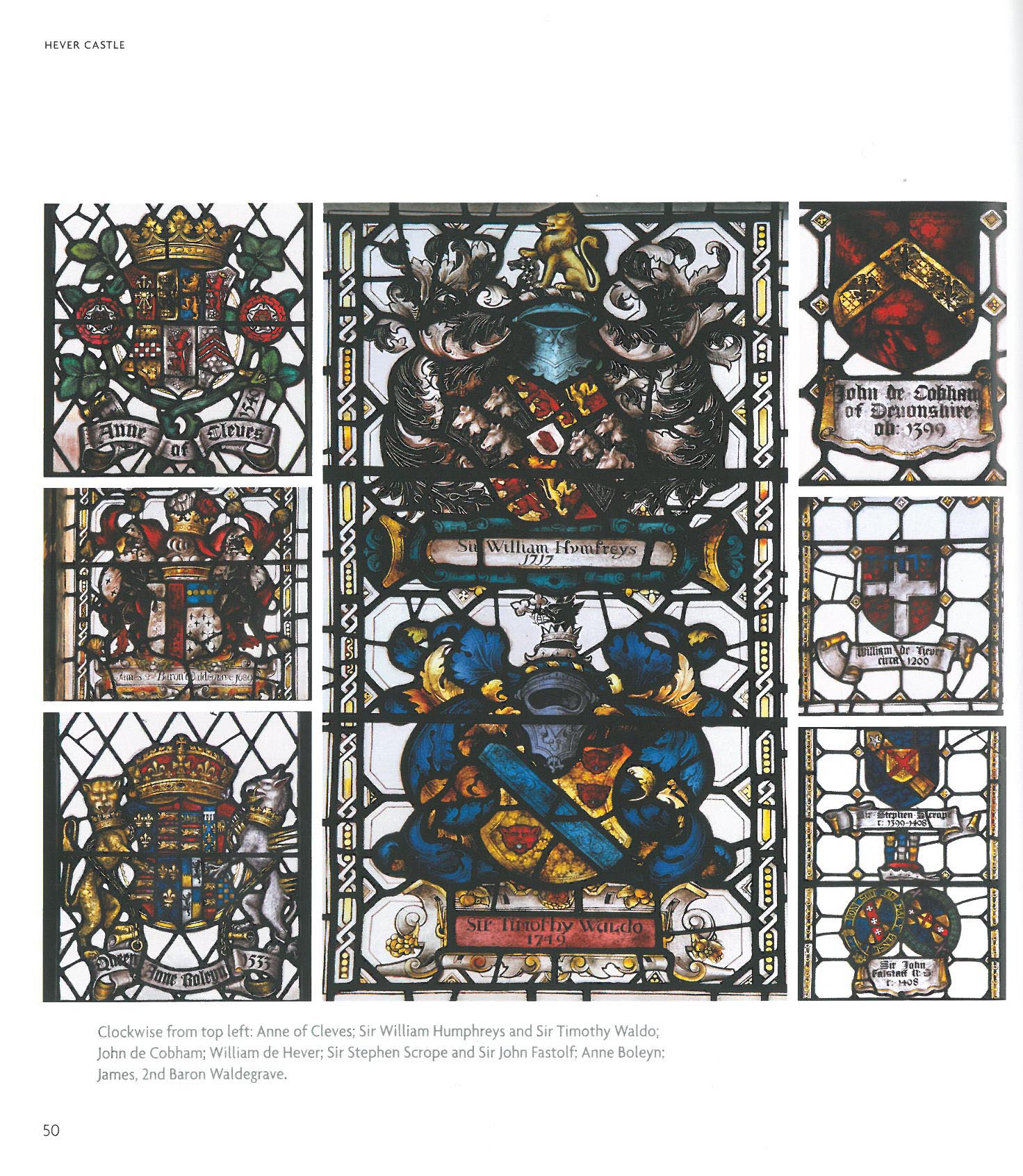

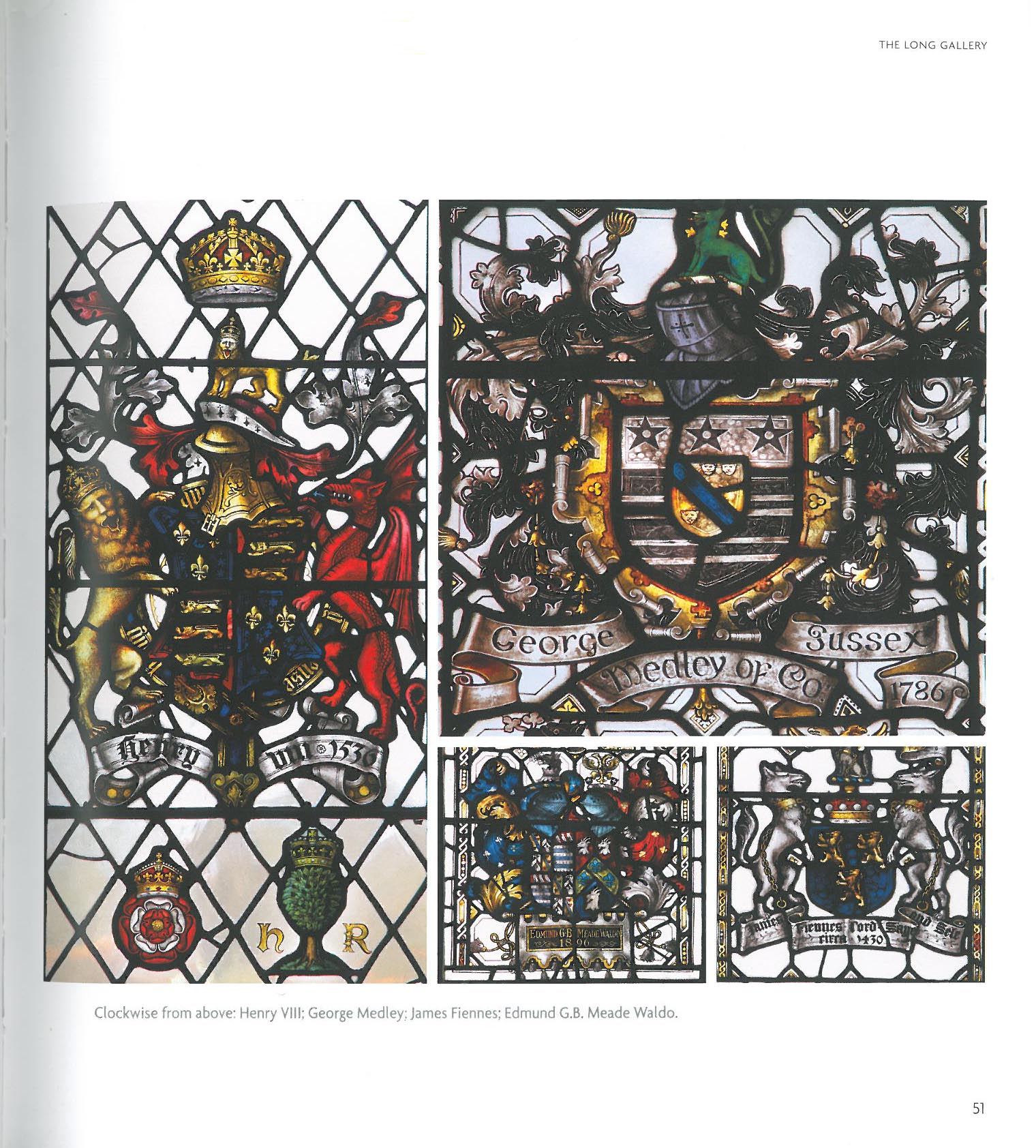

Stained Glass Windows in the Long Gallery. These commemorate the different owners of Hever Castle. Image courtesy of Hever Castle.

What Hever Castle’s moat-side garden probably looks like, right now. Image courtesy of Hever Castle.

Overall, Hever Castle is more a place of historical significance, than a garden of enchantments. To my eyes, William Waldorf Astor’s gargantuan landscaping efforts, while impressive, are hard to love. The outdoor constructions are grandiose but devoid of a unified personality. Astor’s collections of Garden-Caboodle seem random…a disciplined curator’s eye isn’t evident in his hodgepodge of decorative elements. But the Castle itself–modestly-sized and quite cozy, as castles go—still seems as if it could be a Home, and so as I peered out of its windows and down into the water of the moat, and walked through its humanely-scaled rooms, it was easy to imagine that someone REAL named Anne Boleyn had once enjoyed the same views, and trod upon those same creaky floorboards. Just as our Hever-Tour came to a close, the skies finally released the torrent they’d been promising, and so Amanda and I took lunch-time refuge in the Guthrie Pavilion Restaurant (which is adjacent to the Rose Garden), where we enjoyed some very tasty comestibles. Amanda–bless her–made very sure that our intensive touring was fueled by frequent food-stops!

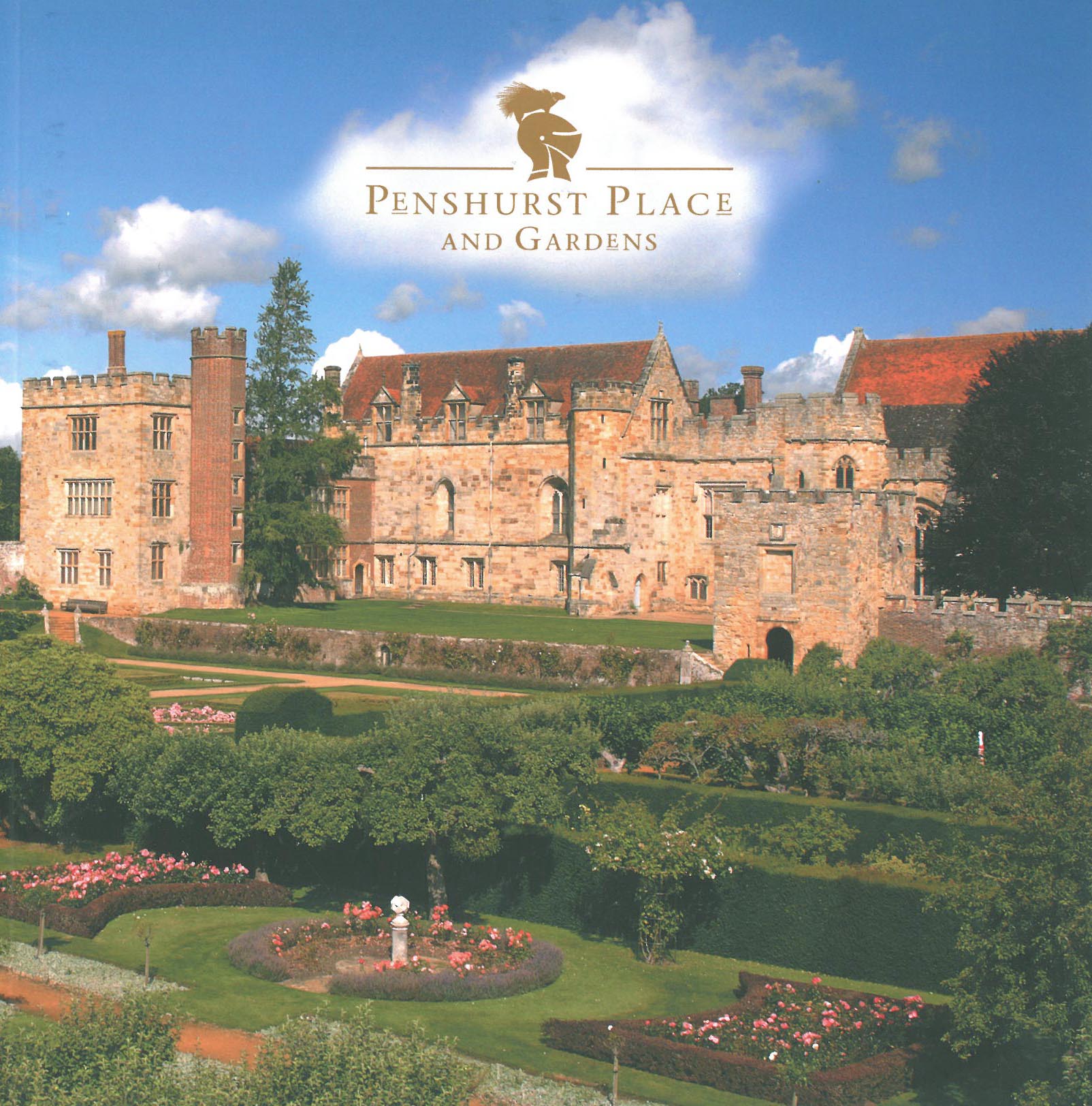

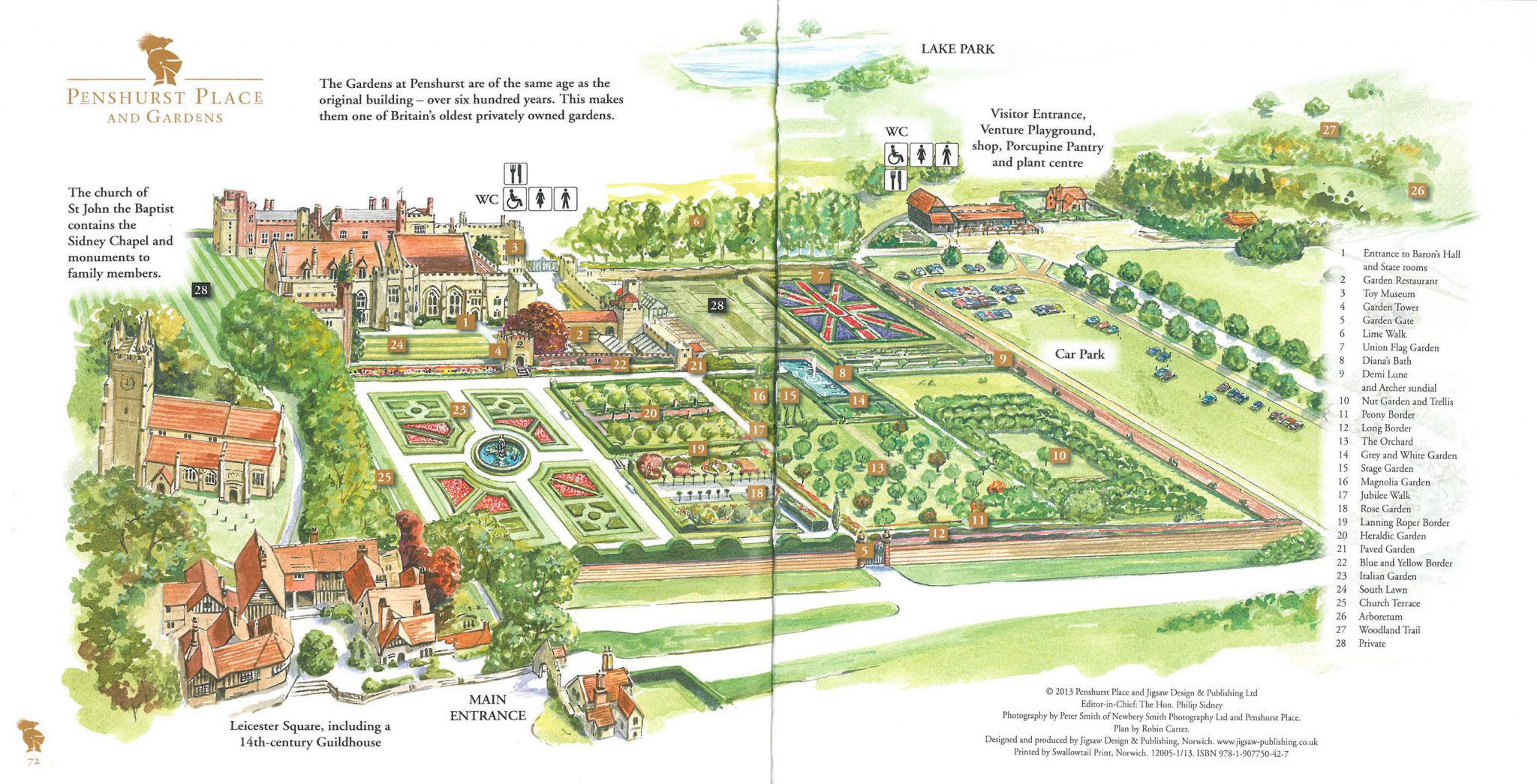

Destination #3: Penshurst Place & Gardens Penshurst Road, Penshurst, Near Tonbridge, Kent TN11 8DG Open from April through October. Daily. 12Noon-4PM Telephone: 01892-870307 Website: www.penshurstplace.com

Penshurst Place & Gardens. The House was completed in 1341, and much of it remains in its original state. It was built of local sandstone, in the typical medieval manor style, with two wings joined by a central great hall. The principal sections of the historic Grade I Listed Garden retain the same shapes as those which were laid out during the reign of Queen Elizabeth I. Image courtesy of Penshurst Place.

Think of the times in your life when your heart’s been broken; of the times when your devotion to someone has not been returned. Of life’s miseries, loving while being unloved is one of the greatest woes. Of course, the greatest woe of all comes at the death of a loved one. But unrequited love is right up there on the pain-scale. Now—even if you’re not of a poetic bent—take a moment to read the following sonnet. And read it aloud: poetry is better heard than seen.

Astrophel and Stella, Sonnet 1, by Sir Philip Sidney “Loving in truth, and fain in verse my love to show, That she, dear she, might take some pleasure of my pain, Pleasure might cause her read, reading might make her know, Knowledge might pity win, and pity grace obtain, — I sought fit words to paint the blackest face of woe, Studying inventions fine, her wits to entertain, Oft turning others’ leaves, to see if thence would flow Some fresh and fruitful showers upon my sunburned brain. But words came halting forth, wanting Invention’s stay: Invention, Nature’s child, fled step-dame Study’s blows, And others’ feet still seemed but strangers in my way. Thus great with child to speak, and helpless in my throes, Biting my truant pen, beating myself for spite: ‘Fool’ said my Muse to me, ‘look in thy heart and write.’ ”

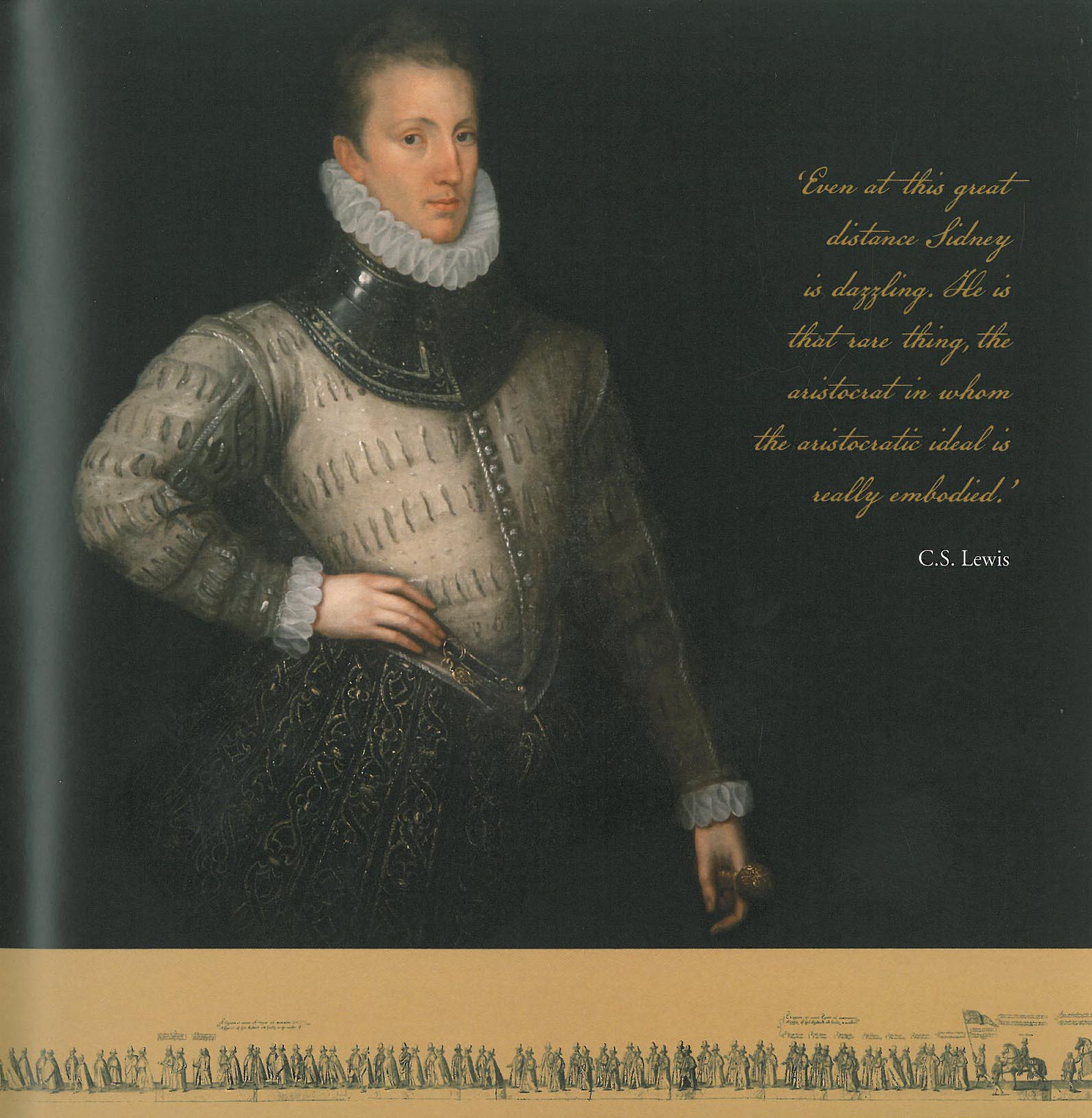

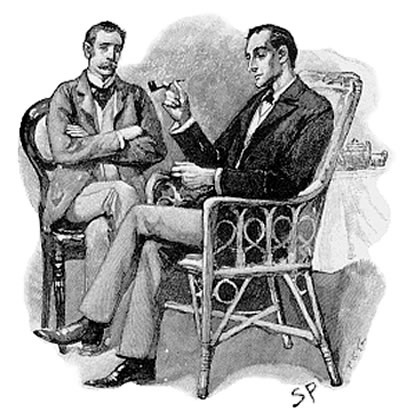

Sir Philip Sidney’s Lover’s-Lament-and-Artist’s-Introspection, written in the voice of Astophel, about his beloved Stella, who is married, is a poem that (…pardon my sort-of French) seriously kicks-ass…and on so many levels. I can describe my reaction to Sidney’s work in no other way! So, who was this poet, who is so closely identified with Penshurst Place?

The Penshurst guidebook explains: “Philip was born at Penshurst Place on 30 November 1554, and named after his godfather Philip II of Spain, husband of the then British monarch Mary I.” [Note: First-born daughter of Henry VIII, by his first wife, Catherine of Aragon. Mary, as Queen, was assigned the adjective “Bloody,” as she restored Roman Catholicism as the official religion of England.] “Intelligent and politically aware, he was to become a brave soldier and patron of the arts. Being a writer himself, he was intent on raising the standards of literature in England.” “Philip was only human—he was said to have a fierce temper and apparently capable of being recklessly extravagant, impetuous and inclined to be difficult. However, as a great figure of the English Renaissance, Sir Philip Sidney, Elizabethan heir to Penshurst Place, and nephew of the Queen’s favourite Robert Dudley, is justifiably praised for his literary work.” “Following his years at Christ Church, Oxford, Philip traveled extensively in Europe, mixing with many of its leading figures, poets and artists. On a later trip overseas, canvassing support for the formation of the Protestant League of Princes to oppose Catholic powers, he was to meet William, Prince of Orange, on whom Philip made a deep impression. He also spent considerable time at Penshurst and at court, waiting on Elizabeth I. Finally he gained the Queen’s reluctant permission to fight for the Protestant cause in the Low Countries, in a rebellion against Spain. In September 1586, on the battlefield at Zutphen, he was hit in the leg by a musket blast. As Philip lay mortally wounded he is said to have ignored his own thirst and passed his water bottle to one of the other soldiers, with the words: ‘Thy necessity is yet greater than mine,’ a phrase which has become immortalized in the English consciousness. In a matter of weeks, in Arnhem in the Netherlands, he had died from his wounds.” “Sir Philip was afforded the honour of a State funeral at St.Paul’s Cathedral, where he is buried. He was the first commoner to receive such a tribute, and it was not repeated until the death of Nelson, and later, Sir Winston Churchill, who had Sidney blood in his veins.”

Sheep Heaven at Penshurst Place. It’s impossible for me to NOT get excited, every time I see an English field full of these creatures. At the end of our 5 days of touring, Steve Parry gave me a book titled KNOW YOUR SHEEP. I confess I haven’t yet memorized its contents, but someday, when I do indeed Know My Sheep, you’ll have to endure a travel article about nothing BUT the many varieties of sheep in England! Image courtesy of Penshurst Place.

As Amanda led me into the Gardens at Penshurst, I could sense her excitement. For all of the places she’d taken me thus far in Kent, her enthusiasm and knowledge had been great, but as Amanda told me about the Baron’s Hall that we’d soon see at Penshurst, and which the writer John Julius Norwich has described as “one of the grandest rooms in the world,” I understood that Amanda has a special emotional attachment to Penshurst Place. As our time there passed, I began to feel the same affection for the elegant but comfortably understated gardens, and for the ancient House. And it was at Penshurst that Amanda introduced me to “The License to Crenellate” (more about this in a bit). HOW, as an architecture-buff, had I existed, for all my years, without knowing about such a Thing?

We entered the grounds via the Lime Walk, an avenue of large-leaved lime trees (planted with Tilia platyphyllos & Tilia vulgaris)

The Porcupine on the Sidney Family Crest is embodied in this large sculpture, which was commissioned to celebrate the millennium, and made by Robert Rattray. The stone base bears a Pheon, or Broad Arrow, which is the Sidney Coat of Arms

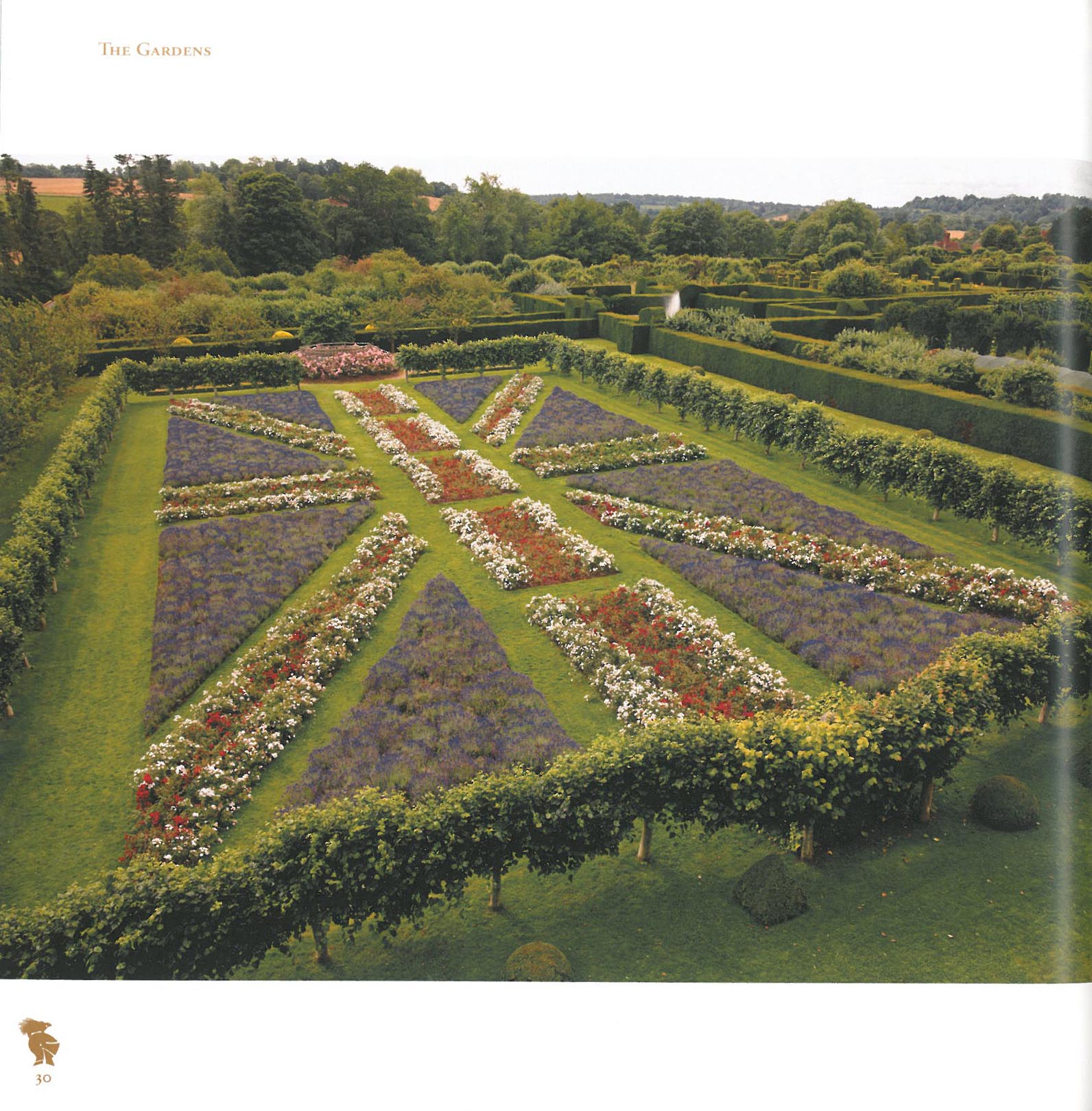

Lawn walks run around all four sides of the still-invisible Union Flag Garden (which is to the left, behind the hedge). Although the gardens at Penshurst are laid out as grids, of various sizes, it’s still easy to become pleasantly lost while wandering from garden “room” to garden “room.” One would not anticipate such a four-square layout to yield a constant sense of mystery; it’s almost as if the entire Garden is a Maze.

We penetrate deeper into the Gardens. A series of yew hedges, which subdivide 11 acres of ground into a series of small garden “rooms,” and which total a mile in length, were planted in the 19th century.

A peek at the picnic grounds, in the fields beyond the Gardens. The estate originally consisted of 4000 acres.

A Pedestrian’s view of the Union Flag Garden, which is (obviously) a contemporary addition to the Penshurst landscape. The plantings: Lavandula ‘Hidcote Blue’ ; white ‘Kent’ Roses; red ‘Chilterns’ Roses. This is my least favorite part of the Gardens.

A heroic but over-ambitious attempt to create a Topiary Porcupine. A Porcupine was a symbol of invincibility: porcupines throw spines at their enemies!

A more successful topiary effort: this one a Bear With Ragged Staff, which is the heraldic symbol of the Dudley family. Sir Henry Sidney married Mary Dudley in the 16th century.

An other-worldly and perfectly-pruned corridor of large globes of Irish Yew, and Hedges, with a glimpse of the House.

Diana’s Bath, which was formed from an Elizabethan Stew Pond. These Tudor pools were stocked with fish, and provided handy, fresh food for the kitchens of great houses.

Hedges enclosing Diana’s Bath. Look carefully at the top of the arch in the hedge. The bottom of the distant gate in the stone wall looks almost like an eye, which is suspended from the arch. I’m sure this marvelous effect was unintended, but it’s wonderful, nonetheless!

Steps down to Diana’s Bath. The water jet in the Bath marks the center of the only view that can be had, right through the middle of the Gardens.

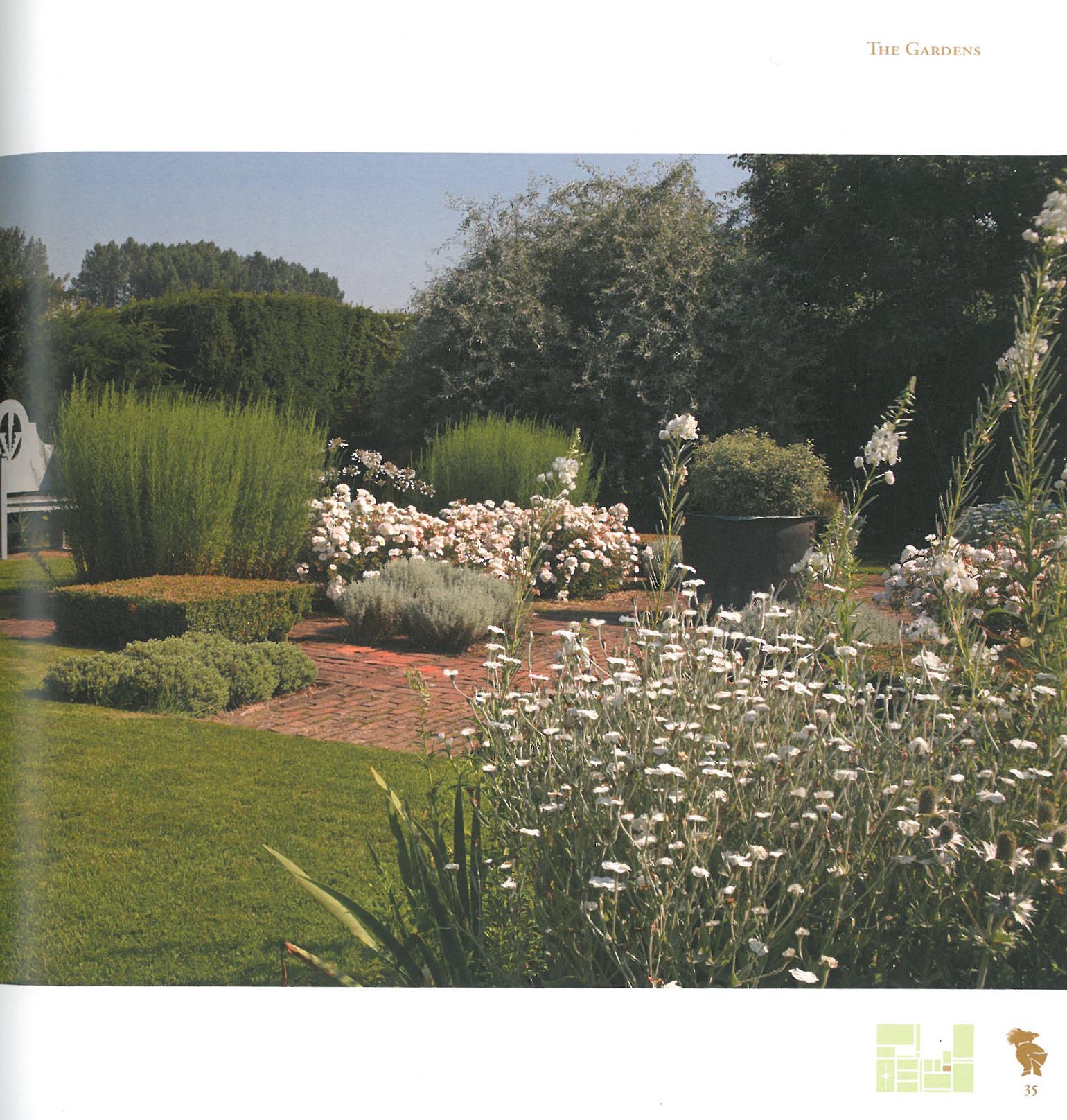

The Grey & White Garden is adjacent to Diana’s Bath. This area was designed by John Codrington in the 1970s, with a mix of white, grey and silver plants, all of which were chosen for their drought-resistant qualities.

The Orchard (which is next to the Stage Garden) is planted with apple trees that are pruned in an umbrella shape, for optimum cropping and picking. In Springtime, thousands of daffodils and other bulbs bloom beneath the trees. Sir Henry Sidney’s son, Sir Robert, established the Orchard, where peaches and apricots were grown, along with apples.

Prime Magnolia-bloom time was past by August, but this one blossom held on, in the nearby Magnolia Garden.

The Jubilee Walk was added to the gardens in 2012, and designed by George Carter, a RHS Chelsea Flower Show Gold Medallist. The Walk is 236 feet long, and planted as a double herbaceous border, with each of the five bays planted in a dominant color, the sequence moving from red through orange, yellow, and pink to blue.

The Heraldic Garden abuts The Jubilee Walk. The Heraldic Garden’s edged beds are partitioned by box hedges containing sage and lavender. The painted poles, always the focus of heraldic gardens, are topped with various beasts…all symbols of the Sidney family.

By August, the blossoms in the Lanning Roper Border had faded, but the view of the spire of the church of St. John the Baptist was magical.

From the Rose Garden: a different view of the church of St. John the Baptist. In 1744, thousands of Dutch box roses were planted here.

We’re looking down the Long Border. The Jubilee Walk begins at the Garden Gate in the wall that contains the Long Border. Beyond the hedgerows the Orchard can be seen.

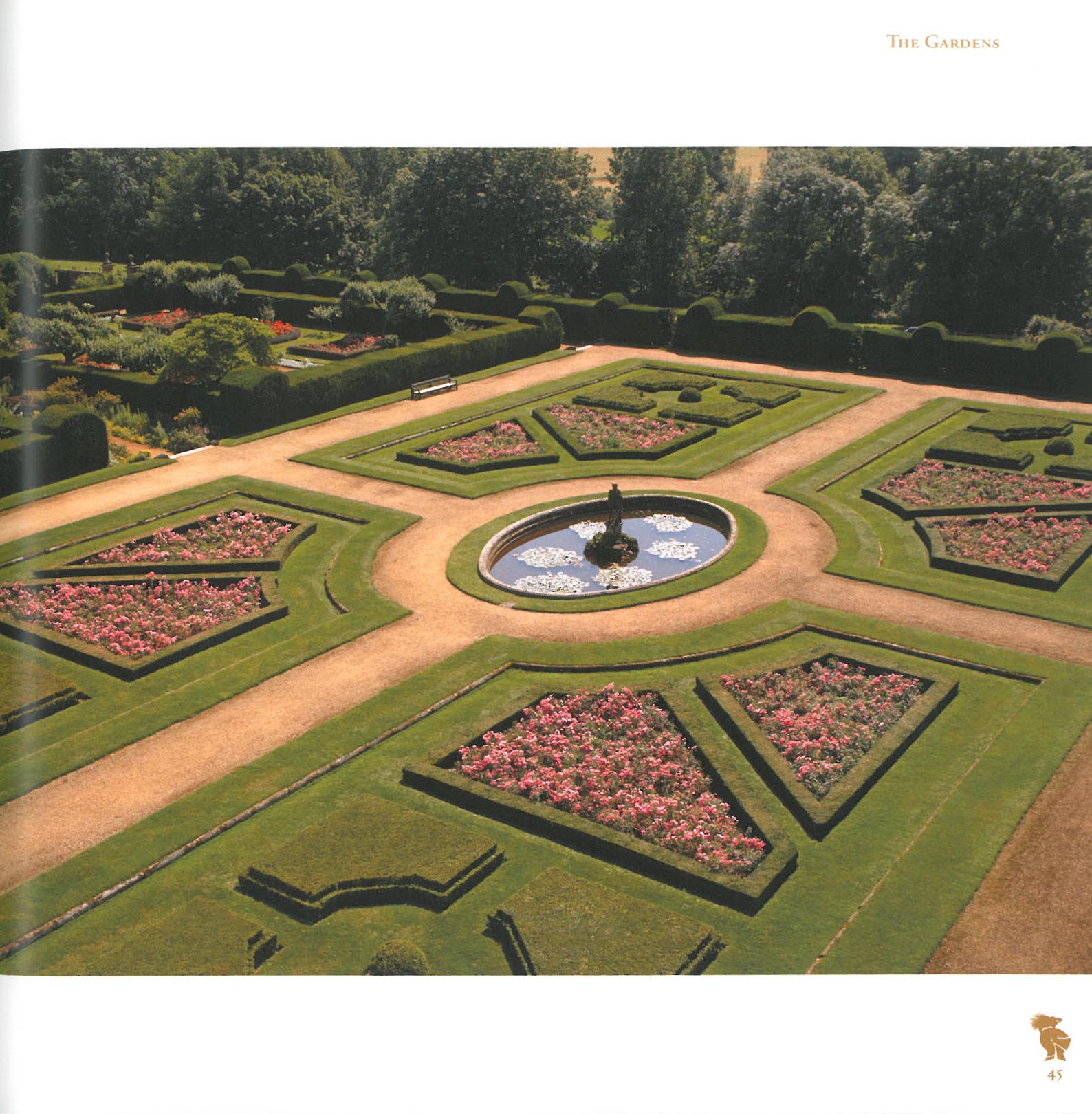

Our first view of the Italian Garden, or Parterre Garden, and the south face of the House. Sir Henry Sidney built the Italian Garden in the 1560s.

The fountain at the center of the Italian Garden. The statue is of a young Hercules, and was moved to Penshurst from Leicester House, in London. The gabled roofs of similarly-named Leicester Square, which includes a 14th century Guildhouse, are visible to the left, behind the high wall.

OK now…time for a bit of Crenellation-Explanation. In medieval England, before a homeowner could add crenellations to his roof line…

…his King (or a County ruler) had to grant him permission to fortify his battlements with crenellations. This granting of a Licence to Crenellate wasn’t done to raise money for the King. Rather, crenellations were conferred upon those knights, nobles, wealthy commoners, and clergymen whom the King thought worthy of his approval. Thus, crenellations became more the architectural symbols of high social status than the actual, defensive features of a building. The House at Penshurst was built in 1341 by Sir John de Pulteney, one of the wealthiest men in England…due to his being a moneylender to King Edward III. By the late 1330s, the Crown was up to its eyeballs in debt to de Pulteney, and so I imagine that Sir John’s request to crenellate was granted with great speed; even a king understands that it’s wise to keep one’s creditors happy! But Penshurst’s crenellation wasn’t always simply cosmetic. In 1401, Sir John Devereux, who’d inherited the estate through marriage, was so alarmed by his memories of the Peasants’ Revolt of 1381 that he ordered the construction of an actually EFFECTIVE wall to enclose his entire House. The Manor was barricaded behind a high series of crenellated curtain walls and turrets, with a total length of 1310 feet. All that’s left today of that defensive wall is the Garden Tower, which serves as entry-point to the House.

The full expanse of the south side of the Manor House, as seen from the Italian Garden. The Garden Tower is to the far right in this photo. Image courtesy of Penshurst Place.

The Paved Garden hugs a corner of the House. The small pool is filled with water hawthorne, and the terrace is shaded by a mature Acer palmatum.

We climbed steps to the South Lawn, for a higher view of the Italian Garden. Water shortages were afflicting Kent in August, as the parched lawns indicate.

As we prepared the enter the House, we admired its ancient sandstone walls. They’ve worn VERY well, haven’t they?

Well, WELL! Now within the cavernous Baron’s Hall, I understood what all the fuss was about! Image courtesy of Penshurst Place.

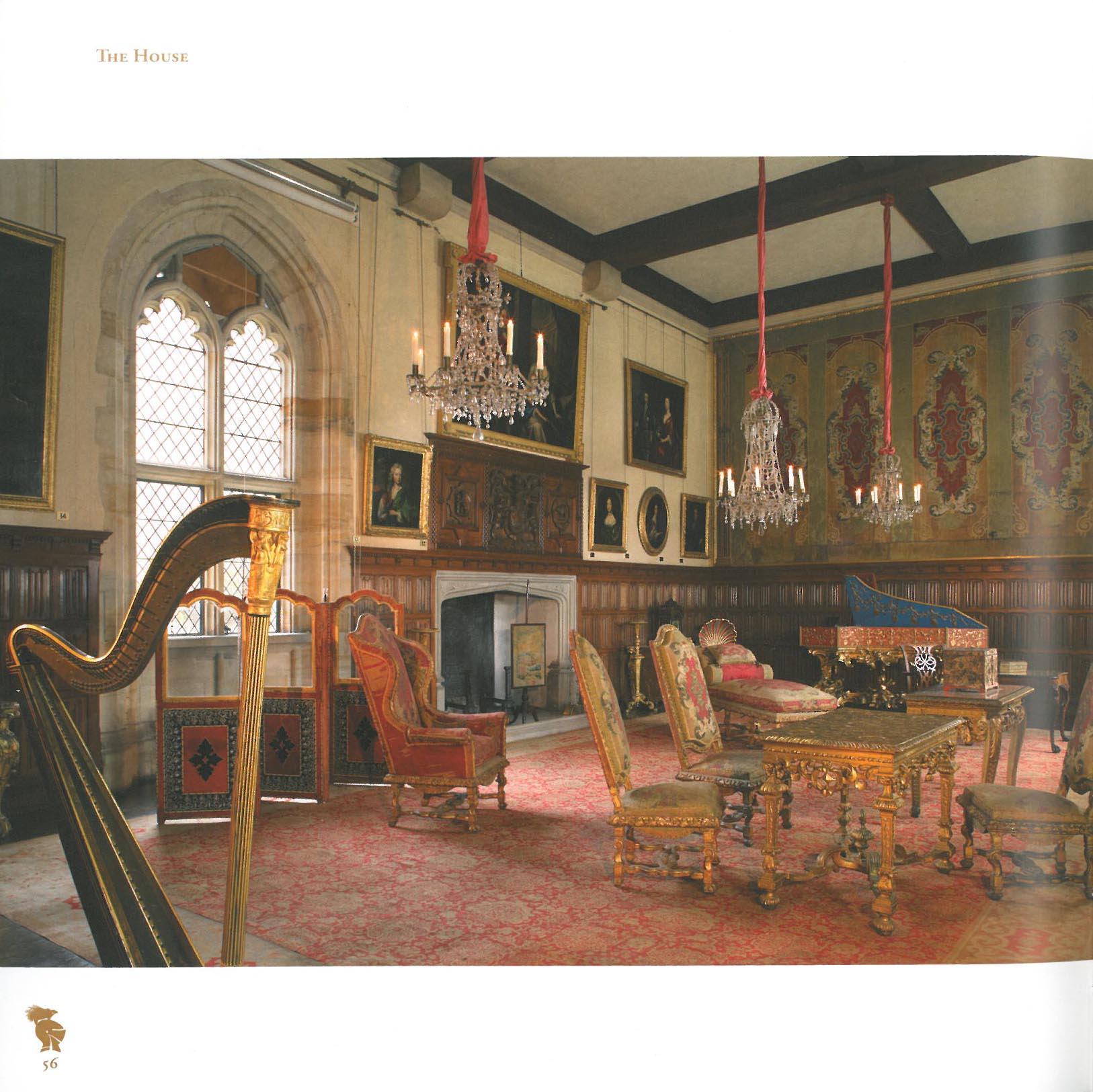

Even on that warm, August afternoon, the air inside the Baron’s Hall was chilly, and I pulled on my sweater. Here’s what the Penshurst guidebook has to say about the space: “The Baron’s Hall is the very heart of Penshurst Place. Belonging to the original part of the house, the Hall was completed in 1341 by the owner Sir John de Pulteney. It measures 62 feet long by 39 feet wide and soars 60 feet high. The architect chose chestnut for the roof design, as it is stronger and lighter than the usual oak. Crown posts rest on collar beams, held in place by huge arched supports, with ten life-size wooden figures hanging down, believed to be satirical representations of peasants and workers at the manor. The tall, arcaded windows reach almost to the floor, flooding the hall with light. Traces of the original 14th century glass can be seen in the top row window above the Minstrels’ Gallery; the Gallery itself was added later in the 16h century. At the dais end of the Hall, the original windows have been blocked by later additions to the house. In the centre of the floor, which was originally earth strewn with rushes, is a unique octagonal hearth. From here, smoke from the fire escaped through a vent in the roof.”

From the Baron’s Hall, we proceeded up a series of stairways, to de Pulteney’s West Solar—which is now the State Dining Room.

To continue the Guidebook’s history lesson: “The Solar [now the State Dining Room] was the withdrawing room of the medieval house. There is a little window—a squint—opposite the fireplace, useful for keeping an eye on what was happening in the Baron’s Hall below. Originally the room would have been lit from three sides rather than one—the reveals on the wall facing the entrance door and the archway at the far end show where the original windows would have been. The fireplace is the 14th century original, albeit with a surround and hood from the mid 19th century after refurbishment. The fine dinner service with the Royal Coat of Arms was given to Philip Sidney and Sophia FitzClarence by her father, later King William IV, on the occasion of their marriage.”

And more from the handy Guidebook: The Queen Elizabeth Room, “and the next, the Tapestry Room, are the first additions to the original house made by the Duke of Bedford, who lived here in the early 15th century. It was built as one large room, a first-floor hall or Great Chamber much like the Baron’s Hall downstairs. Sir Henry Sidney had the room divided in two and also halved the height by the installation of the present ceiling and the building of another set of rooms above. Queen Elizabeth I would have used it to give audiences on one of her many visits. The set of daybed, winged armchair, and six high-backed chairs with their original rose damask and green silk embroidery, have matching hangings. These date from the late 17th century and are a particularly luxurious, and indeed unique, survival from the period. The harpsichord, formerly owned by Queen Christina of Sweden, was purchased by the then owner of Penshurst Place, William Perry, in the 18th century.”

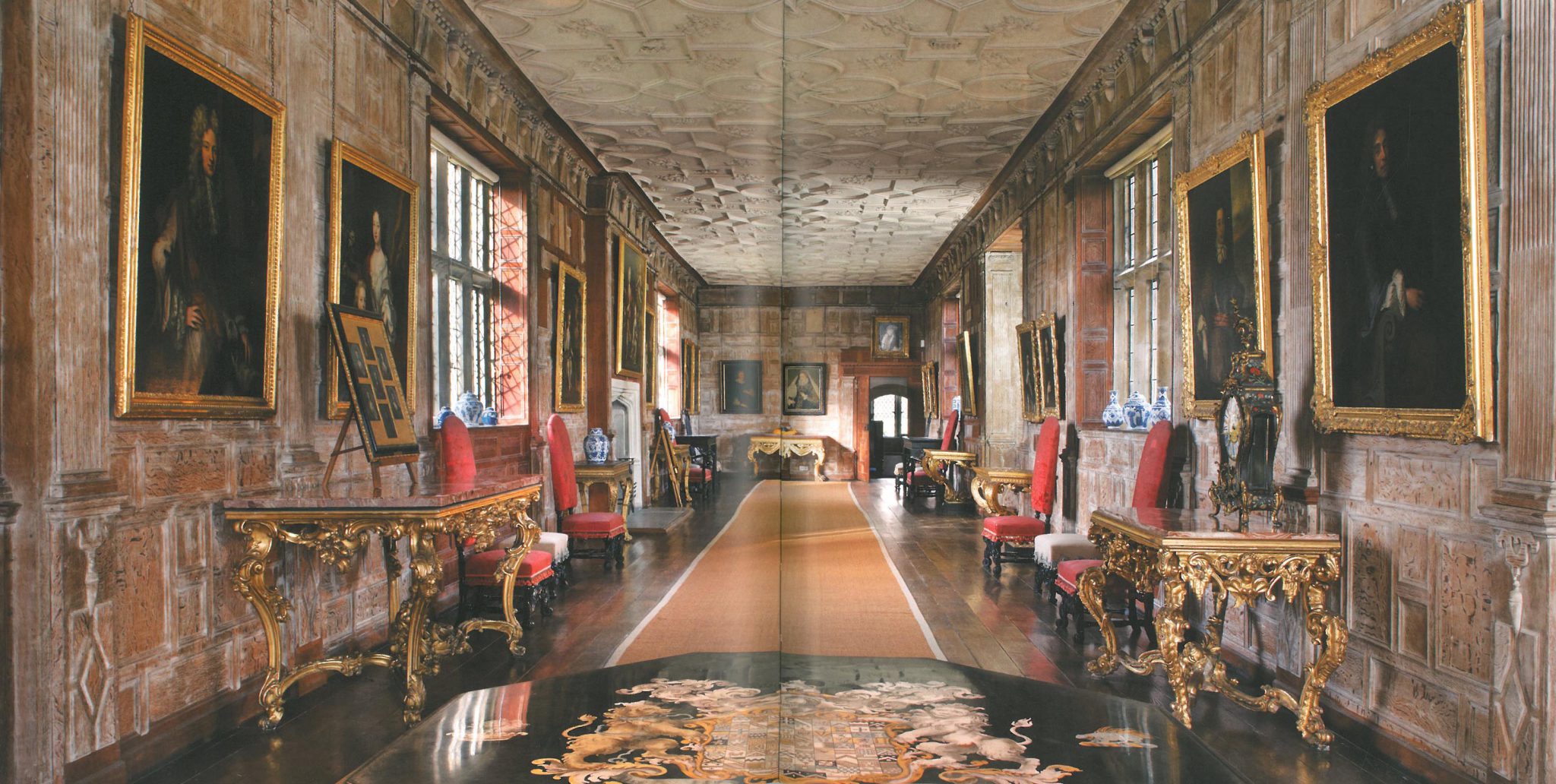

We wrap up our House tour with the Guidebook’s description of the spectacular Long Gallery: “The wing that includes the Long Gallery was started in 1599 and built by Sir Robert Sidney and his wife Barbara Gamage. Long galleries were very fashionable at the time and were used for taking exercise and showing off portraits, tapestries and furniture. It is unusual in being lit by windows on three sides. The fine paneling is original-—painted dark brown in the 19th century and then bleached as it was stripped. The paintings are arranged to illustrate the history of the house and of the family during the first two centuries after Sir William Sidney came to Penshurst in 1552. Over the door, as you enter the room, hangs a portrait of King Edward VI, who gifted Penshurst Place to the Sidney family in 1552. The costumes on display are from the film adaptation of Philippa Gregory’s historical novel THE OTHER BOLEYN GIRL, filmed at Penshurst.”

All these symbols of Bears brandishing tree trunks puzzled me, so I did a bit of heraldic-research. Upon the death of our Poet, Sir Philip Sidney, ownership of Penshurst went to his brother, Sir Robert Sidney, who was also heir to two Dudley family uncles, the Earls of Warwick, and Leicester. The Bear and Ragged Staff is a heraldic sign, normally referring to Richard Neville, the Earl of Warwick (1428—1471) who was known as the “King-Maker.” Bear-baiting was considered manly sport… and apparently the First Earl slew a bear by strangling it. But the Second Earl went one better: he brained a bear with a ragged staff—a young tree that had been stripped of its branches—and so chose this delightful memento of his boldness and courage as the Dudley family’s Symbol. A final, delicious, it’s-a-Totally-Small-World note about Penshurst Place. Just as Anne of Cleves was granted Hever Castle as part of her divorce settlement with Henry VIII, so too was she given Penshurst Place. Anne of Cleves was a VERY-finely-propertied former Queen…and one upon whom Fortune ultimately smiled, as she managed to outlive Henry’s other wives. We should all enjoy such lucrative divorces as the “Flanders Mare’s!” Eventually, Henry VIII’s son, King Edward VI, chose to bestow Penshurst upon his valued tutor and household steward, Sir William Sidney, and thus began the Sidney family’s ownership of Penshurst, which still continues, as Philip Sidney, 2nd Viscount De L’Isle, Her Majesty’s Lord-Lieutenant for the County of Kent (what a mouthful!) lovingly cares for his house and gardens. The present-day Philip Sidney tends his treasure with reverence, but his role isn’t merely custodial, as is evidenced by his many, inspired additions across the grounds. My photographs of Penshurst’s predominately-green gardens cannot convey the sense of peace that my wanderings there gave me. And the awe that I felt, as I stood on the cold paving stones of the floor in the Baron’s Hall and gazed up at the 674-year-old chestnut roof trusses—which, miraculously, haven’t succumbed to fire, as so many ancient, wooden roofs do—was beyond description. Yes, sometimes even I, who can chatter on and on, am struck dumb by the magnificence of England’s cultural heritage!

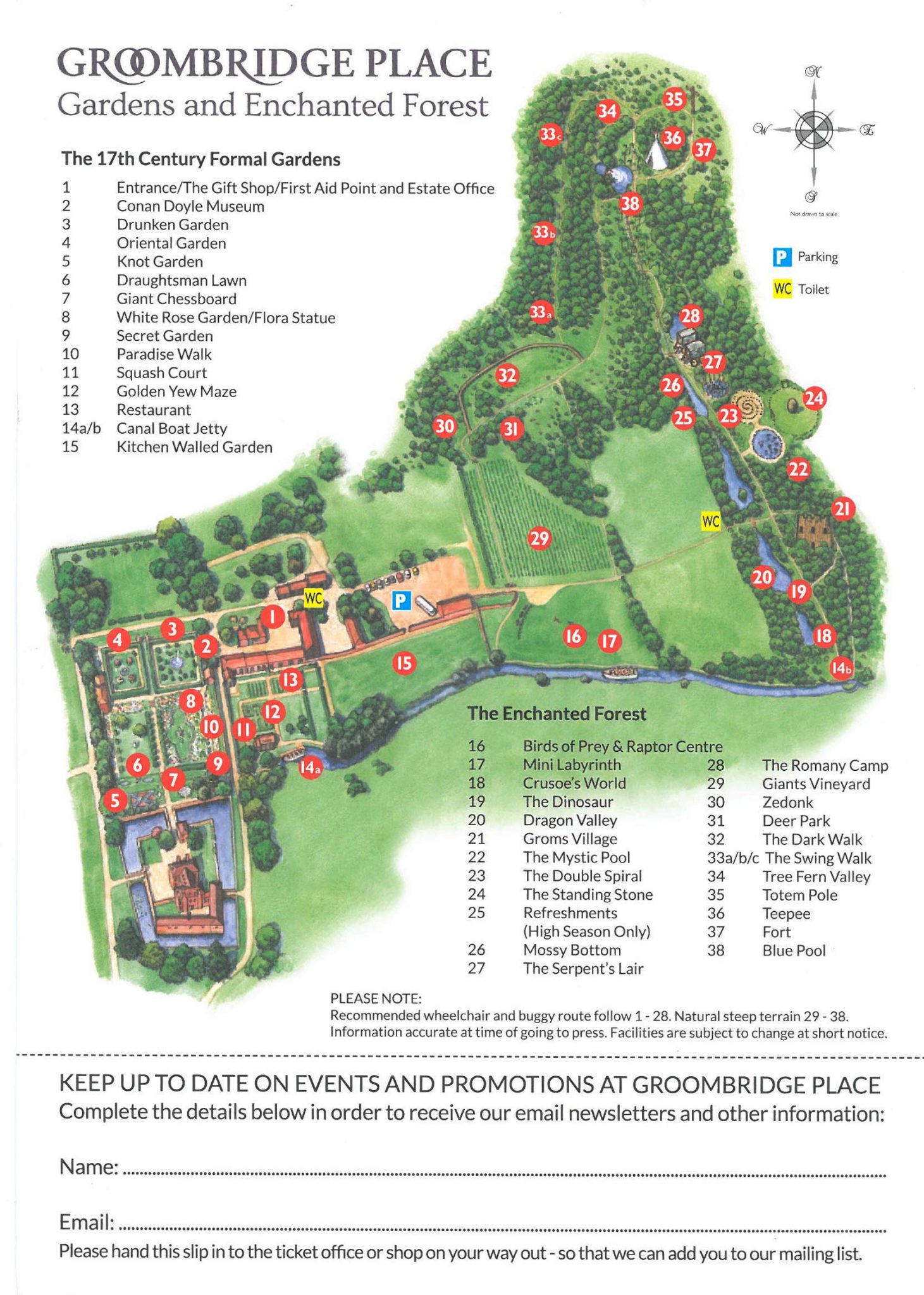

Destination #4: Groombridge Place Groombridge Hill Groombridge, Near Tunbridge Wells Kent TN3 9QG Open April through October. Daily, 9:30AM—4PM Phone: 01892-861444 Website: www.groombridgeplace.com

The moated, 17th century Manor House at Groombridge Place. Image courtesy of The Danewood Press Ltd.

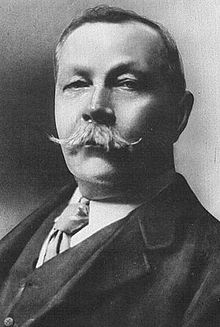

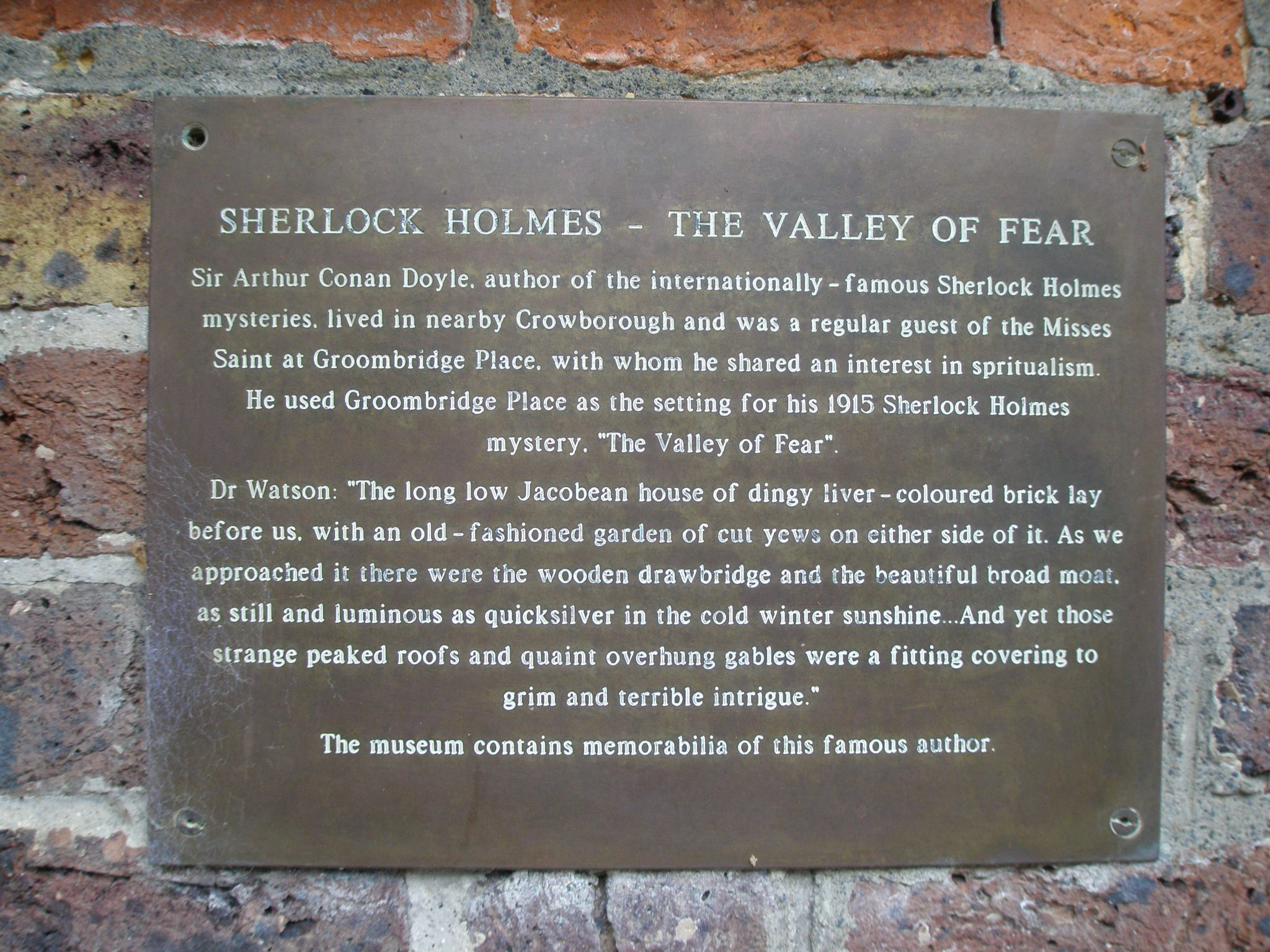

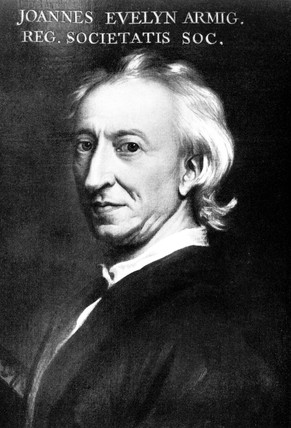

After all of Monday’s Historical Gravitas—what with our visits to the homes of Winston Churchill, and Anne Boleyn, and Sir Philip Sidney—the day’s final destination sounded like it would be quite….ORDINARY! How spoiled I’d already become, that I could consider the merely-350-year-old Groombridge Place, where nobody in particular apart from Sir Arthur Conan Doyle had lingered, to be Ordinary! Sigh….clearly, the glories of Kent had sent me a bit off my rocker. God knows how much three MORE days of Kent-touring would skew my perceptions. But I’m a huge Sherlock Holmes fan (during the summer of 2010, I reread all of Conan Doyle’s Sherlock-stories), and so as Amanda explained that Conan Doyle set scenes from THE VALLEY OF FEAR at a manor house based upon Groombridge, my traveler’s eyes started to become UN-jaded. Ever since 1239, a moated house of some sort or other has been on the site of the present manor at Groombridge Place. Today’s visitors look across the moat at the house that was built in 1662 by architect Philip Packer, with input from his young friend, Christopher Wren (who would eventually become THAT Christopher Wren). Amanda had brought me to see the gardens, the oldest parts of which have the same vintage as Packer’s house (the house isn’t open to tourists, and looks as though it’s been suffering from neglect). Directed by the noted horticulturalist John Evelyn, Philip Packer laid out the Grand Allee of 12 pairs of drum yews that we see today, the expanse of grass that’s now called Draughtsman Lawn, the White Rose Garden, and the Secret Garden.

We began our garden ramble with a stop at the little Arthur Conan Doyle Museum that’s been erected on the grounds. Conan Doyle lived in nearby Crowborough (which is just over the border, in East Sussex), and sometime before 1914 became friends with Groombridge Place’s sisters Louisa and Eliza Saint, who shared his loopy convictions about fairies and spiritualism. The Sainted-Sisters often invited Conan Doyle to their séances, and Conan Doyle swore he’d seen—and spoken to—a ghost, who hovered alongside the Groombridge moat.

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859–1930): creator of Sherlock Holmes…and a believer in fairies and ghosts.

Arthur Conan Doyle used Groombridge Place as the setting for THE VALLEY OF FEAR, but renamed the house Birlstone Manor

Dr.Watson….in Groombridge Place’s Drunken Garden (and yes…”Drunken Garden” is an Official Gardening Term).

A glimpse of the House, from within the Drunken Garden, where even the spouting water seems a bit off-kilter.

The Narrow Path that separates the Drunken Garden from the Oriental Garden. The House is in the distance.

The Cottages adjacent to the Oriental Garden offer excellent examples of Kentish tile-hung walls. This method of covering the exteriors of timber-framed houses first appeared in the late 17th century. The tiles are hung on oak laths, with the upper part of each tile bedded into a lime and hair mortar known as “torching.” The laths are hung overlapping to give a triple lap, which results in a weathertight wall.

We look down over the upper reaches of Draughtsman Lawn, and then further toward the 12 pair of ancient drum yews.

As we approach Draughtsman Lawn, I’m reminded that Peter Greenaway’s 1982 film THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT was filmed entirely at Groombridge Place. The film’s premise: an artist is hired to make 12 drawings of the grounds at a manor house. The lady of the house, who cannot afford the artist’s services, insists, however, that the artist MUST find a way to for her to pay for his work. Of course, the contract that’s eventually agreed upon involves both the lady of the house and her daughter: they’ll provide their sexual services, in exchange for the artist’s drawings. And of course, there’s a surprise twist at the end.

Scene from the film THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT, after one of the 12 “payments” has been made to the Artist. Image courtesy of Peter Greenaway.

I’ve just watched the movie, and, although it’s not a stunning piece of drama, it does pose interesting questions about the difference between SEEING things, as opposed to KNOWING things. But because Greenaway filmed in the most painterly fashion imaginable, watching his little manor-house-mystery gave me great pleasure. Every scene is composed and lit with an artist’s eye, so if you want to experience the gardens at Groombridge without an Atlantic flight, all you need to do is order the film from Amazon.com.

Scene from the film THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT. The Artist is set up, on the same Draughtsman Lawn that Amanda and I walked across. Image courtesy of Peter Greenaway.

Scene from the film THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT, with actors on the Draughtsman Lawn. Image courtesy of Peter Greenaway.

Scene from the film THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT. The Artist has set up this frame, to help with his perspective drawing. Image courtesy of Peter Greenaway.

Scene from the film THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT. This is the drawing of the Yew Allee that the Artist produced for his client. Image courtesy of Peter Greenaway.

The Reality of the Grand Yew Allee. This time, we’re looking toward the House. Picture taken on August 5, 2013.

The Knot Garden, which is between the inner and outer moats. The House is encircled by the much wider inner moat.

Scene from the film THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT, with actors on the Side Bridge. Image courtesy of Peter Greenaway.

Scene from the film THE DRAUGHTSMAN’S CONTRACT. In the front court, an al fresco dinner, lit only by candles. Image courtesy of Peter Greenaway.

I wouldn’t dare to swim in this water, but this is apparently where Sir Arthur Conan Doyle’s ghost-acquaintance liked to hang out.

My final look at the forlorn but charming Manor House, at Groombridge Place…but it DOES look a bit haunted, doesn’t it?

Having reached the end of our second day of Power-Touring-Through-Kent, I was more certain than ever that Jane Austen hadn’t misled anyone. “The Garden of England” may not be the ONLY place for happiness, but, in terms of density-of-marvels-per-square-mile, and judging from Kent’s ability to inspire its residents to concoct all sorts of wonders—gardens, and castles, and poems, and histories, and stories, and films— I’d say that there are few other spots on Earth where so many treasures are so closely packed. Get some rest now, because Kent-Part-Three is in the works. We’ll visit a tiny country church, with stained glass windows by Marc Chagall. We’ll get a fast tutorial in hops farming from Steve Parry. We’ll explore Scotney Castle, which seems to be a fairytale, made real. We’ll delight in the eccentric collection of garden sculpture at Pashley Manor. And we’ll elbow our way past the tour-bus crowds, and climb the Tower at Sissinghurst.

Copyright 2014. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

4 Responses to Part Two. Rambling Through the Gardens & Estates of Kent, England