The circular, late 14th century tower at Scotney Castle, near Royal Tunbridge Wells, in Kent. This is as close to fairy-tale as life ever gets.

February 2014.

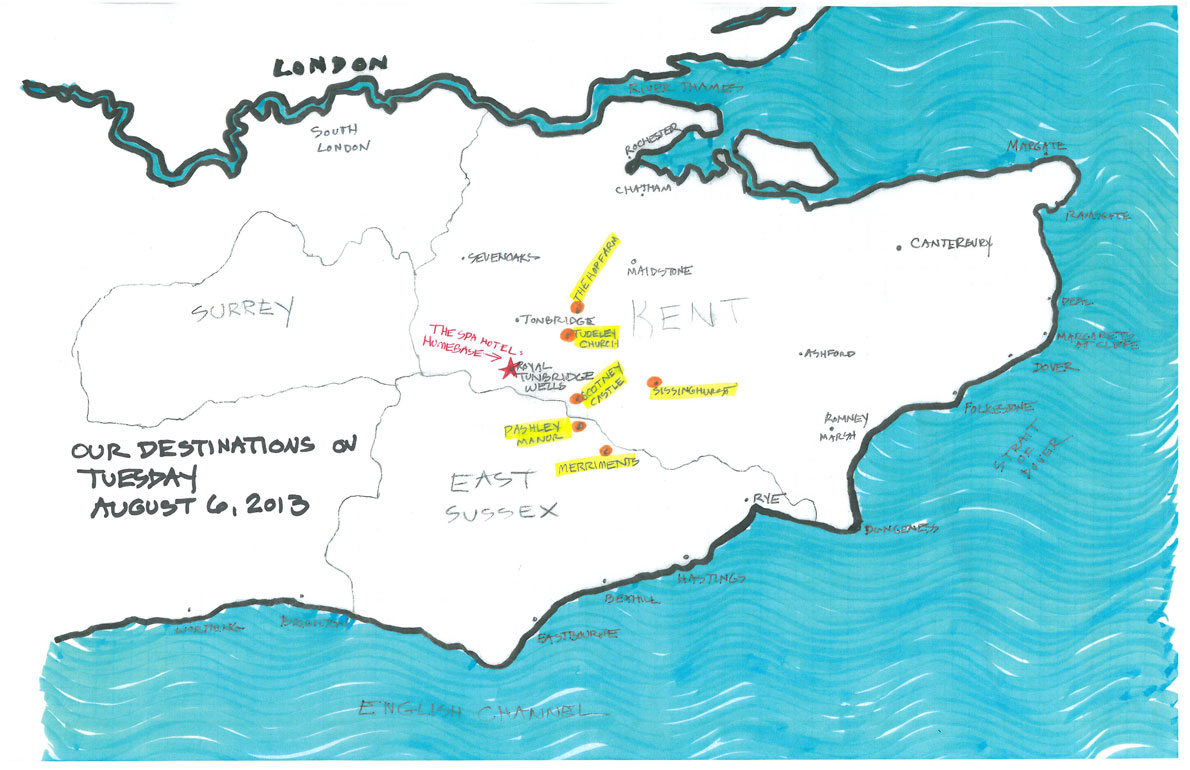

On Tuesday, August 6, 2013 my meanderings through Kent continued, as I was led by extraordinary

Blue Badge Guide Amanda Hutchinson ( www.southeasttourguides.co.uk ),

and expertly driven to our destinations by Steve Parry ( www.snccars.co.uk ) .

By this, the third day of our travels, Amanda and Steve and I had settled into a jovial and comfortable companionship; it seemed as if we’d known each other forever. As we shuttled from place to place, we found more and more to laugh and to talk about, and whenever I’d express interest in something that Amanda hadn’t originally planned for me to see (Sheep Pastures—can’t get enough! Hedge-rowed Lanes—the narrower the better! Country Churches—bring ‘em on! Hop Farms—show me the Bines! And NO that’s not a typo: ”Bines” will soon be explained.), she and Steve would seamlessly weave an extra feature or two into the day’s itinerary. I realized my cohorts were determined that every one of my questions be answered; that every one of my enthusiasms be satisfied. And so our Tuesday included a grab-bag of Kent-Marvels, which seemed to encompass everything… from the Heavenly, to Hops.

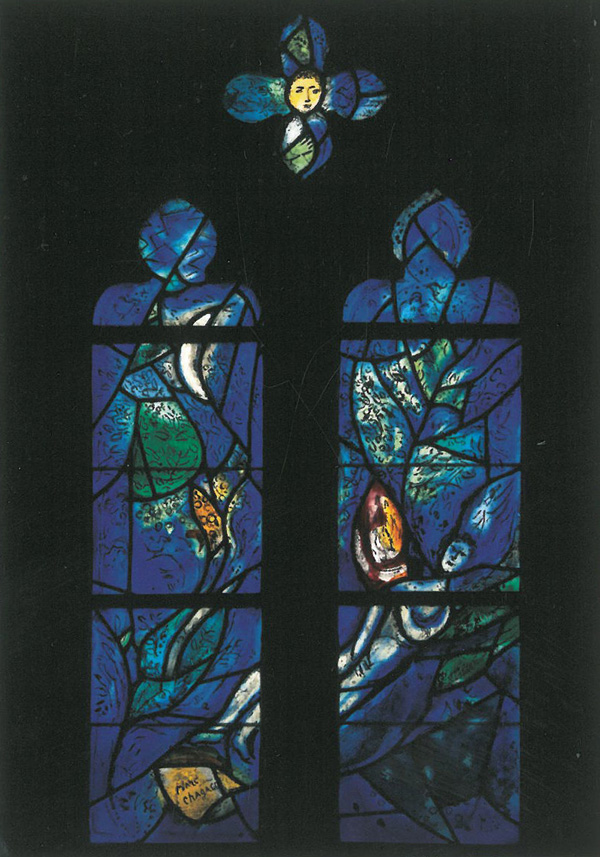

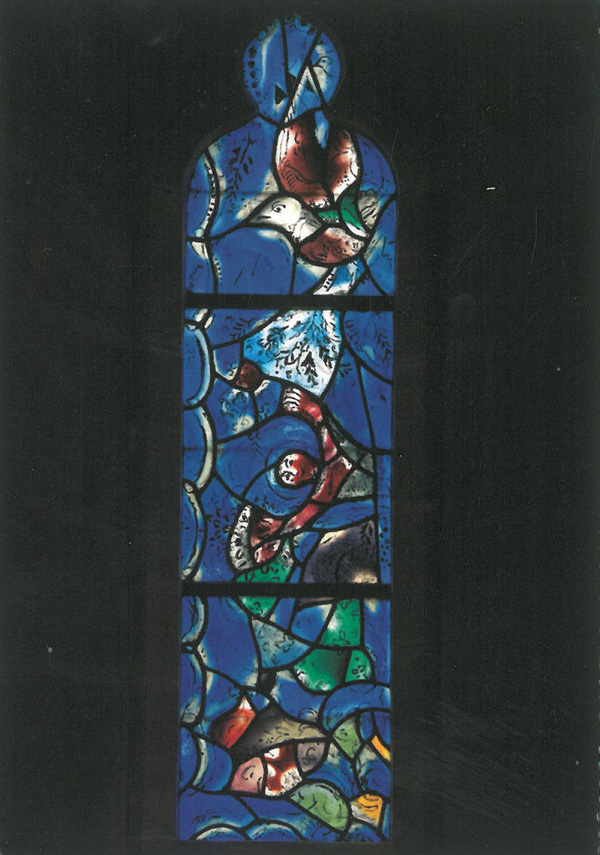

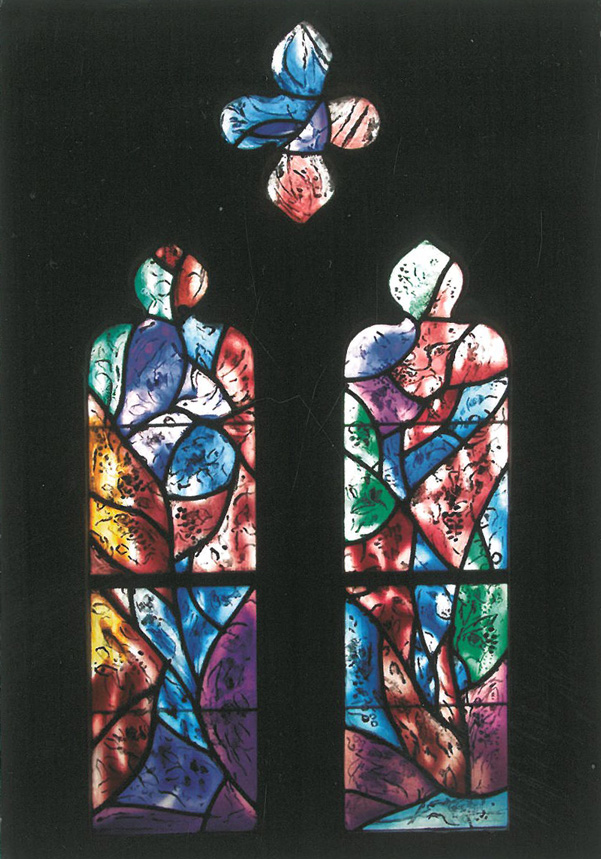

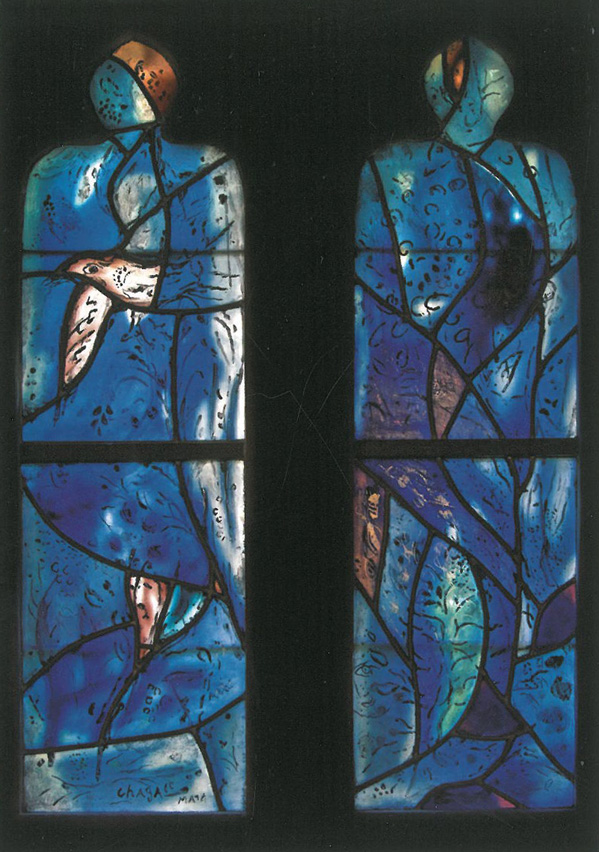

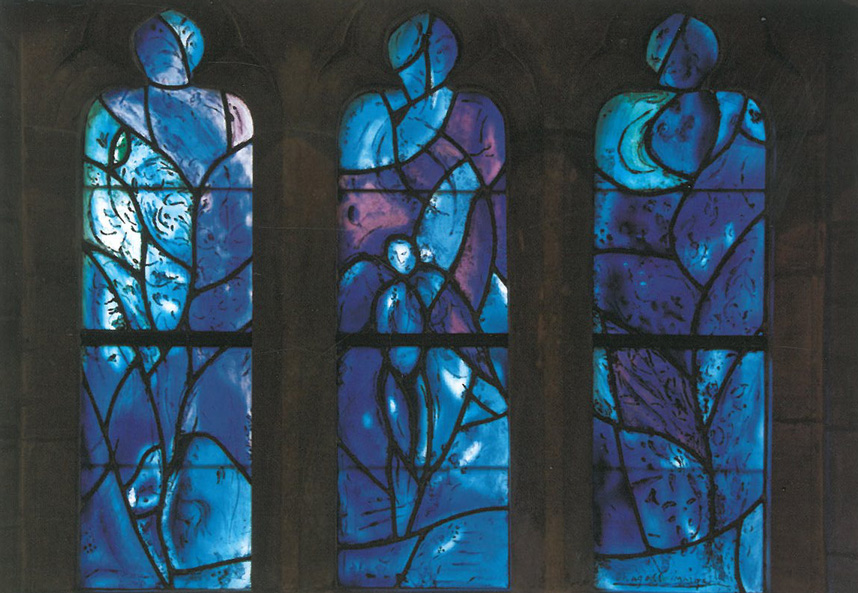

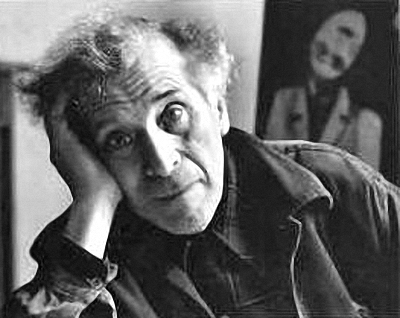

The day began with sunshine…a fortunate thing, because bright light is needed to illuminate Marc Chagall’s sublime stained glass windows at tiny All Saints Church, in the hamlet of Tudeley.

Destination #1: All Saints Church

Five Oak Green Road

Tudeley

Near Tonbridge

Kent TN11 0NZ

Website: www.tudeley.org

The Church is open daily, from 9AM to 4PM, but since it’s a Real Church, when normal activities are underway (Sunday and Monday morning services, Saturday weddings, music festivals, etc., etc.) the Church is closed to tourists. Choose a mid-weekday-morning, like we did, and you’ll be fine.

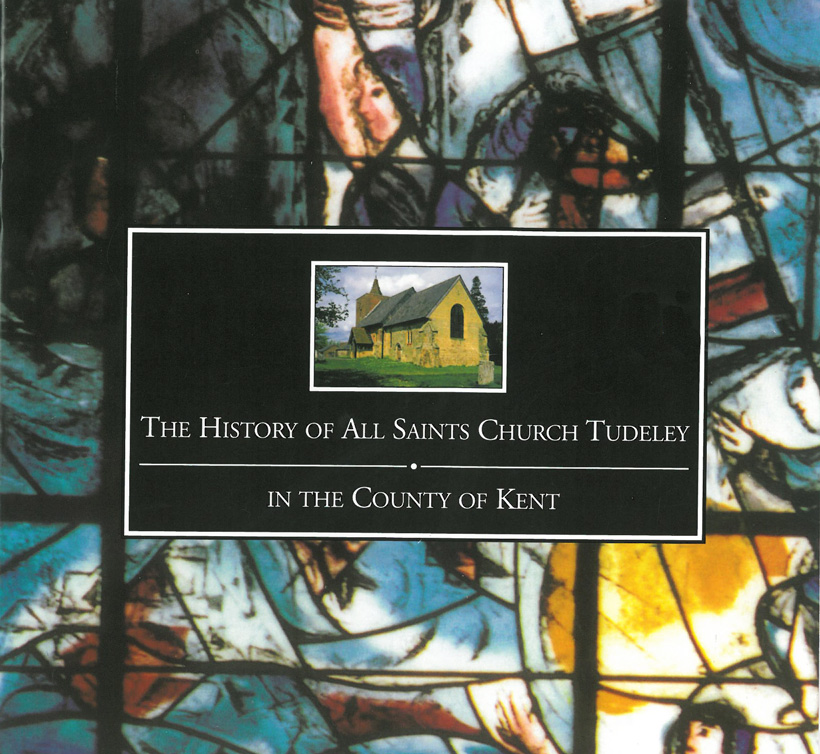

All Saints Church at Tudeley is the only small church in the world to have all of its windows designed by Marc Chagall. Image courtesy of All Saints Church.

Not until 1956, when Chagall was 70, did he begin to create stained glass windows, and most of those were made for European cathedrals. America has only two small installations of Chagall’s stained glass to admire: his tribute to Dag Hammarskjold is at the General Assembly Building of the United Nations, and his Rockefeller-commissioned windows decorate the Union Church, in New York State’s Pocantico Hills. Chagall’s most soaring expanses of stained glass are in Israel, France, Switzerland and Germany. But the only church in the world where ALL of the windows are by Chagall is tucked away in Kent’s countryside. Getting to All Saints isn’t straightforward…some satnavs can’t find the place. To avoid ending up in the middle of a field, visit the All Saints website, and download directions.

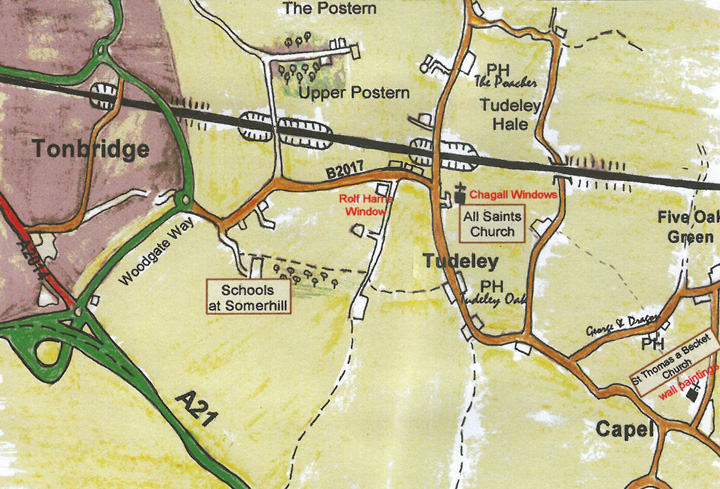

How to find All Saints Church in Tudeley, which, although near to Tonbridge, seems worlds and years apart. Image courtesy of All Saints Church.

The village of Tudeley is ancient. Some historians claim the Phoenicians rowed their galleys up the River Medway to trade for the iron that was smelted there. But there’s no doubt that, by the time of the Roman occupation in 43 AD, forges were indeed built alongside the streams that stretched their fingers through the dense oak forests of the Kentish Weald. Traces of a Roman-era forge still remain, just a bit west of the Church. At the beginning of the 7th century, during the early days of Christianity in Britain, All Saints was one of only four churches in the Saxon kingdom of Kent; the current Tudeley Church is built upon the sandstone footings of a late Saxon period church. But the appeal of All Saints isn’t architectural. The building—which is nestled among apple orchards and hop-gardens and has endured centuries of demolition, rebuilding, and restoration— isn’t remarkable in appearance.

View from the Burying Ground at All Saints Church. Those odd-looking, conical roofs are Oasts…about which MUCH more, in a bit.

All Saints is distinguished by Chagall’s 12 windows, which are on three sides of the main interior space. Those windows transform the humble church into a joyous and exalted place, and came into being because of a family’s great sorrow.

Per the All Saints Church Guide-booklet:

“It was the death in 1963 of a 21-year-old girl under tragic circumstances which led her family and friends to commemorate her name in a lasting and tangible form. Sarah Venetia d’Avigdor-Goldsmid was the eldest daughter of Sir Henry and Lady d’Avigdor-Goldsmid. In September of 1963 she and a companion were drowned in a sailing accident off the coast of Rye in Sussex. In her memory her family and many friends subscribed to the restoration of the interior of the church—a restoration which was designed to provide a setting of utter simplicity for the memorial window that [her father] commissioned Marc Chagall to design. It was when in Paris in the summer of 1961 that Lady d’Avigdor-Goldsmid and Sarah visited the Chagall exhibition at the Louvre. Both were enraptured by Chagall.”

The recollection of their daughter’s admiration of Chagall’s stained glass became the inspiration which eventually led to Chagall’s designs for every window in All Saints Church. In 1967, when Chagall visited the renovated Church for the dedication of his Memorial Window, he exclaimed: “It’s magnificent. “ Then he added: “It’s a very curious thing, but dead architects are the only ones I can work with!”

Chagall’s Memorial Window, at All Saints Church, in Tudeley. The blue-ish light that’s reflected against the walls around the lower portions of the window seems to splash real sea-spray into the air.

As an artistic genre, apotheosis follows certain conventions. The dearly departed is raised upwards by angels, and taken to a place of light and beauty and eternal life. Sometimes a prudent man—such as the Venetian, Barbaro– might commission an artist to paint an apotheosis…BEFORE he’s shuffled off his mortal coil. The existence of such a painting might serve as a suggestion, to the Higher Powers, when death actually comes:

Tiepolo’s magnificent GLORIFICATION OF THE BARBARO FAMILY, which, prior to my discovering Chagall’s Memorial to Sarah, was my most-favorite example of apotheosis art. Image courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.

And sometimes a grateful nation gives a hint about what they’d like to have happen to an esteemed but now-departed leader:

But rarely has an apotheosis been presented in such a dramatic and emotional manner. In Chagall’s Memorial to Sarah d’Avigdor-Goldsmid, the moment of her death is re-enacted, and is followed by the image of her despairing mother. Chagall does not shy away from showing the horrible event; after which come time-lapsed scenes of grief, and of sorrow’s healing, and of everlasting souls. The Church’s Guide-booklet helps us to see how he does this:

“In a series of moving cameos we are drawn into the drama of this young girl drowned in the dark swirling waters of the sea. To the left, in the panel above the floating figure, the mother is seen cradling her two children; while at the lower edge a kneeling figure poignantly expresses the grief of the family and friends. From the turmoil of the sea the girl is being gently borne into calmer waters. A ladder reaches up to the figure of Christ. To the left of Christ there stands an angel figure waiting as though to herald the arrival of the new young souls; one of the girl’s two companions can already be seen at the top of the ladder: meanwhile at the foot the girl is seen preparing to mount the first rung in her ascent to the comforting arms of Christ.”

Chagall’s other Tudeley windows aren’t narratives: with his Main Window, he’d told the story that was most important. Here are some views of those companion-windows:

Although I didn’t know it then, as Amanda and Steve and I left the Tudeley Church, groundwork had just been laid for further Chagall explorations. During the following week of my England-stay, my dear friends Anne and David Guy would spirit me far northward, to see Tate Liverpool’s exhibit of the earliest, and not-widely-known work of Marc Chagall….a plan they’d formed as a surprise for me. Per usual, Serious Synchronicity was afoot in my travel-life.

It’s taken me three-Kent-articles to get to my next subject: the distinctive, conical, pointed roofs that punctuate the horizons of southeastern England. But, from the first moment on that previous Saturday, when my train from London to Royal Tunbridge Wells had crossed into the Kentish Weald, I’d beheld buildings, the likes of which I’d never before seen…at least not in the flesh.

A lady from the late Middle Ages wears a HENNIN, a cone-shaped headdress…perhaps a subliminal inspiration for later, agricultural buildings?

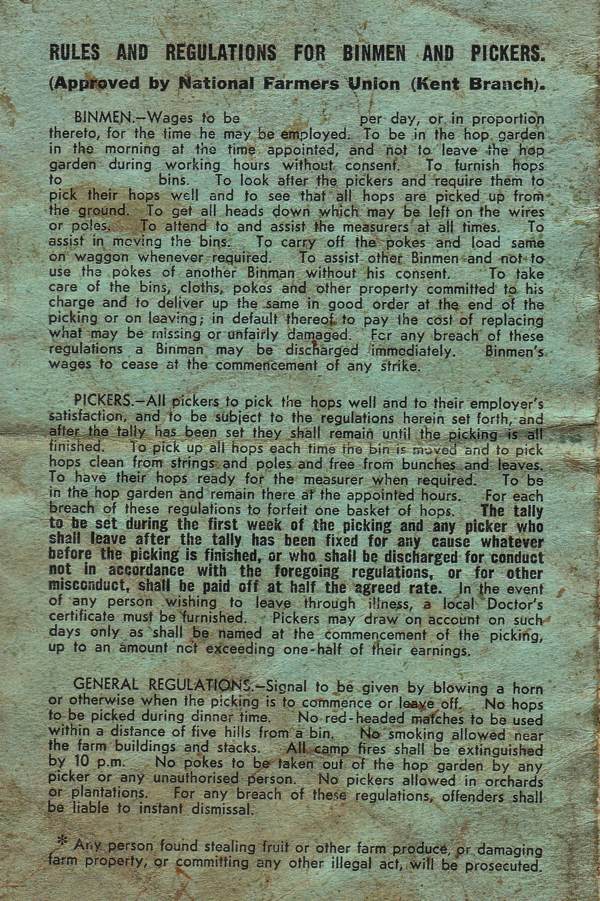

Steve and Amanda had, I suspect, chuckled at my ignorance about Kent’s omni-present Oasts, and thus about Hop Farming…hey, I’ve only intermittently been a beer drinker, and so haven’t spent time in life wondering about how Porter— the Kent-specialty….beautiful, brown, and aromatic — gets made. That morning, when Steve had picked us up at my hotel, he’d brought along a small library of books with vintage photos of Hop Farming in Action. It turned out that Steve has Hands-On-Hopping in his distant past: during his college years, he’d spent one September helping a friend whose family owned a hop farm, and so, as we arrived at The Hop Farm Family Park, the first of two days of a very-thorough-tutorial about All-Things-Hops began.

Destination #2: The Hop Farm Family Park

Maidstone Road

Between Beltring and Paddock Wood

Near Tonbridge, Kent TN12 6PY

Telephone: 01622-872068

Website: www.thehopfarm.co.uk

Unlike the Church at Tudeley, The Hop Farm is located at a major intersection, and is impossible NOT to find.

Set in the midst of acres of “amusements” (childrens’ rides, giant jumping pillows, and funhouses) at the Hop Farm Family Park there remains one of the best-preserved complexes of traditional Oast Houses in England. My companions led me on a fast walk around the majestic structures, as Steve explained the process of hop farming, and of hop drying.

At first, for a tyro like myself, understanding hop-growing and harvesting wasn’t easy. The best website overview of Hop-History is provided by www.hoppingdowninkent.org.uk . Here’s their helpful timeline:

1520: First English hop garden set up near Canterbury, in Kent.

1655: One third of the UK hop crop was produced in Kent

1722: A new beer, Porter, was brewed that was a combination of 3 beers. It used lots of hops and became popular, thus making the hop industry very wealthy.

1744: A law was passed saying that all bags or “pockets” of the dried hops sold had to be stenciled with the year, place, and grower’s name.

1875: Better, and larger-scale methods of training and stringing the fast-growing hop plants were developed.

1878: Hop farming reached its peak, with 77,000 acres of land in Kent under cultivation.

But so as NOT to put cart before horse (or oasts before bines), here first are pictures of actual hop-plants, taken on the morning of Wednesday, August 7th, when we visited the hop gardens at Sandhurst Vineyards and Hop Farm

( www.sandhurstvineyards.com ) . Hops grow rampantly in Kent’s fertile soil. Each April, their roots begin to send out vigorous vines, which are called Bines. By May, those lengthening bines are trained away from the soil,and up onto a series of permanent, and very high trellises, which are constructed of poles which support canopies of string or wire. Prior to the 1950s, when hop-picking machines began to be used…

…workers teetering atop stilts would walk between the rows of plants, and thread bines around the high wires, in a clockwise direction. These stilt-walkers were called “Stringers.”

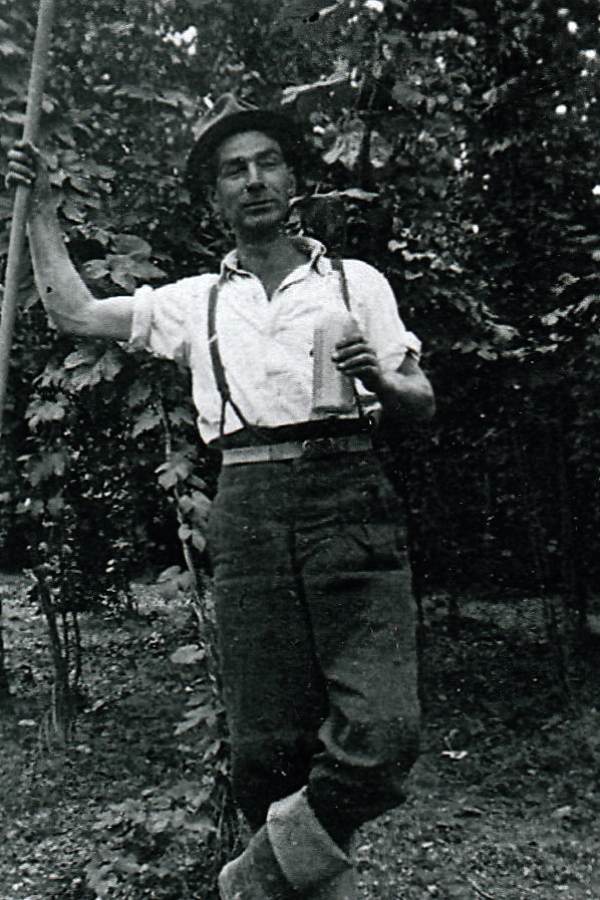

Once the bines had had their tendrils wrapped around the wire, they’d continue to grow like gangbusters. Workers at ground level, who carried long, forked twigs of hazel wood (shades of Harry Potter!), would then use those sticks as wands, to push the drooping bines back, up and over the mesh of overhead wires. Steve, who in his youth wielded such a hazel-wand (he DOES look a bit wizardly, doesn’t he?), worked as a “Stroddler, “ but stroddling is also known as straddling, or heading….colloquial terms abound, from hop-field to hop-field.

Hop Bines, giving Jack’s Beanstalk a run for its money. The Hop Garden at Sandhurst. Hop Bines customarily grow to be 15 feet tall.

UN-ripe Hops, in early August. Hops are harvested in September, when their cones are fully-grown. After they’re picked, they’re dried, and then cooled in specially-built oast houses.

Amanda Hutchinson gamely provides human scale, in the Hop Garden at Sandhurst, on August 7th. Think of how much FUN it would be to walk down these paths on stilts!

Per Hopping Down in Kent, “Hops begin to flower in July. Petals grow and form the cones. Inside these petals yellow lupulin glands form. It is these glands that give out the bitter taste. By September, the cones are ready to be picked from the bines.”

Until the late 1950s, each September, at harvest-time, multi-generational families of working-class Londoners moved, in masse, to the fields of Kent, where they set up camps. These tens of thousands of temporary laborers worked long hours, but most considered their month out of London to be holidays; sojourns which provided them with exercise, fresh air, serious-evening-partying, and extra money.

Now that we’ve seen the Hops Themselves, I’ll return us to the Oasts, at the Hop Family Farm.

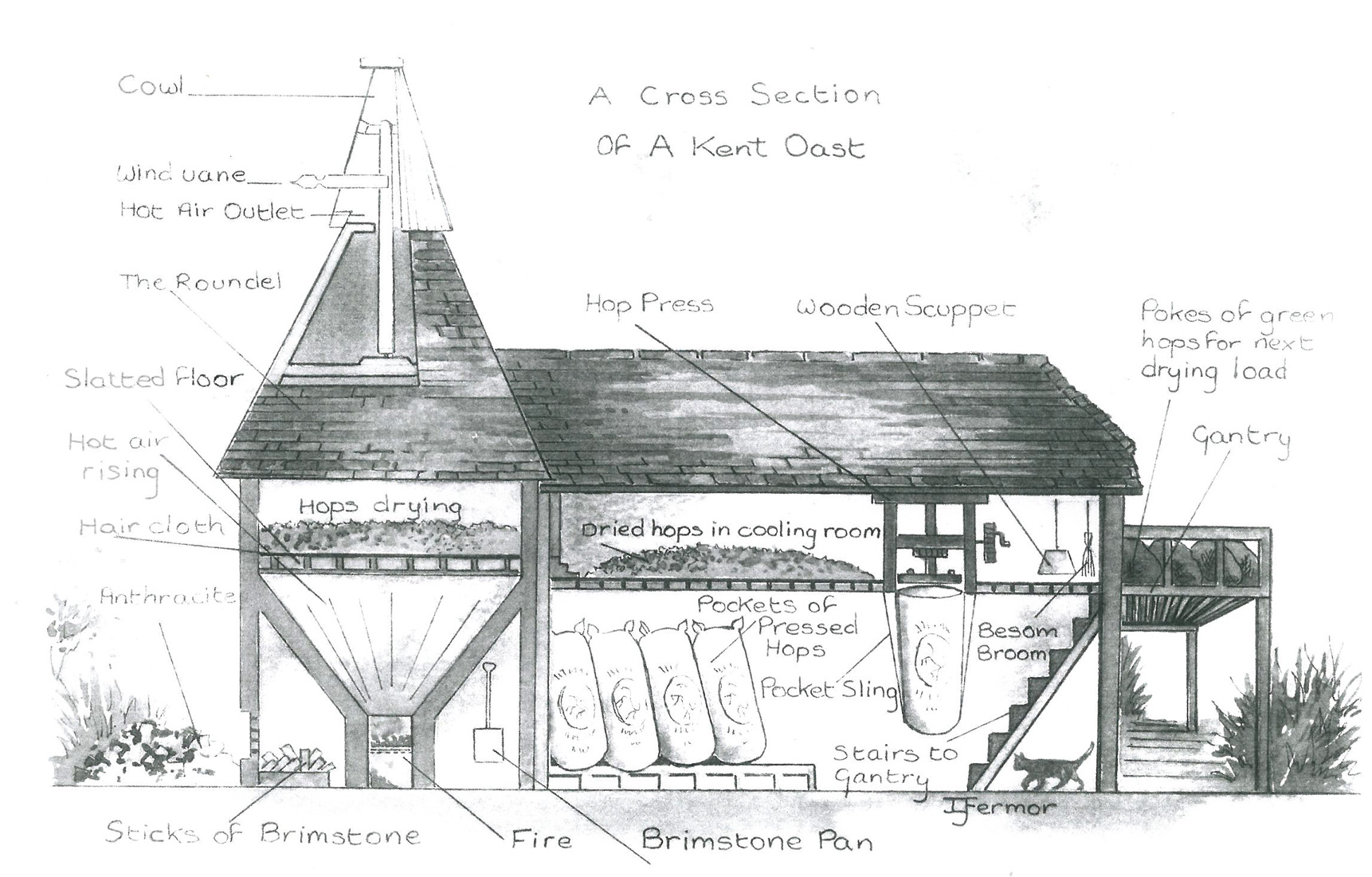

Wikipedia’s Oast House entry sums things up nicely:

“An oast, oast house, or hop kiln is a building designed for drying hops as part of the brewing process. Oasts consist of two or three storeys on which the hops were spread out to be dried by hot air from a wood kiln at the bottom. The drying floors were thin and perforated to permit the heat to pass through and escape through a cowl in the roof which turned with the wind. The freshly picked hops from the fields were raked in to dry, and then raked out to cool before being bagged up and sent to the brewery. By the early 19th century the distinctive circular buildings with conical roofs had been developed in response to the increased demand for beer. Square oast houses appeared early in the 20th century, as they were found easier to build. Hops are today dried industrially and the many oast houses on farms have been converted into dwellings.”

What would ‘The Garden of England” be without its picturesque oasts…the vestiges of agricultural-glory-days? Today, only 3000 acres of Kent are still used to grow hops. Next time you enjoy some Porter, raise your glass to the Stringers and Stroddlers of times past.

Destination #3: Scotney Castle

Lamberhurst

Near Tunbridge Wells

Kent TN3 8JN

Open year-round, weather permitting, from 10AM to 5PM.

Phone: 01892-893820

Website: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/scotney-castle/

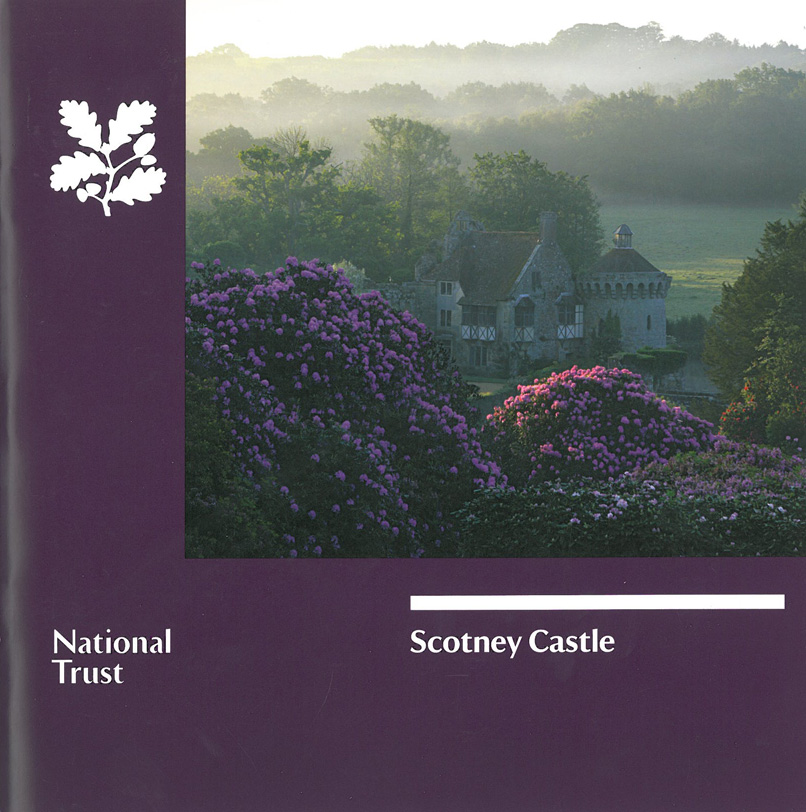

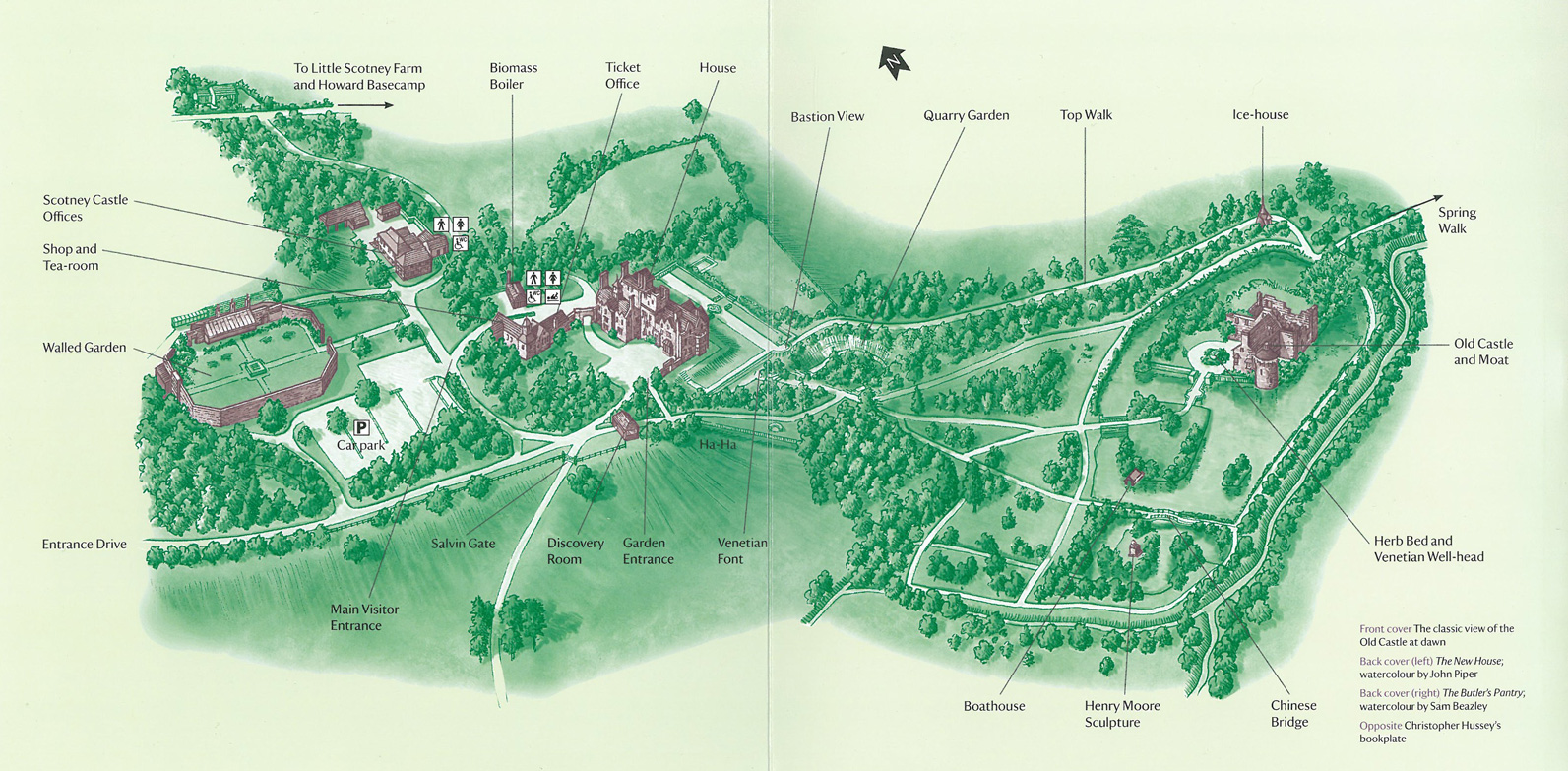

Scotney Castle: a country house, romantic garden, and 14th century moated castle, on 770 acres of beautiful parkland, in Kent. My visit at mid-day on August 6th merely whetted my appetite. Scotney is a place to which I shall certainly return. This is a view of the Old Castle, at dawn, in May. In the foreground, the upper reaches of the Quarry Garden are visible, where massed clumps of rhododendrons—the shrub most-favored by the Picturesque designers—bloom in shades of mauve, purple, rose and white. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

At Scotney Castle, we’re presented with the embodiment of the Picturesque in garden design. The contrast between the Medieval ruins of the Old Castle (which was built by Roger Ashburnham in 1378) and the sturdy Elizabethan-style sandstone walls of the New House ( which was constructed 459 years later) creates a perfect tension, as The Castle’s guidebook explains:

“From the early 18th century, British landscape gardeners had been creating gardens inspired by pictures, but by 1800 a reaction had set in. Critics like the Rev.William Gilpin considered the grassy vistas designed by ‘Capability’ Brown too smooth and tidy. They might be beautiful, but they were not PICTURESQUE: to resemble the best landscape painting, a garden needed drama, variety and rough edges. At Scotney, the plunging site, the mixture of sheltered quarry and open lawn, and the ragged silhouette of the Old Castle provided all three in abundance. “

“Scotney is not one, but two houses, united by art and nature. Surrounded by the moat at the bottom of the valley are the romantic ruins of the Medieval castle. At the top of the hill is the new house, built in 1837—43, for Edward Hussey III. The carefully contrived views between the new and old represent almost the last, and perhaps the most perfect, expression of the Picturesque landscape style.”

The expansive Estate that we enjoy today is the result of land consolidation which began in 1778, when Edward Hussey I purchased the property, with its ancient moated Castle, from the Darrell family, who’d lived there for the previous 350 years. Every generation of the Hussey family, whose motto is “I scarcely call these things our own,” has since put its own stamp on the grounds. Parklands have been filled with specimen trees, streams have been dammed, elegant terraces have been built near to the New House, and romantic gardens have been fashioned in the Quarry, and around the ruins of the Old Castle.

The New House at Scotney Castle was built in an Elizabethan-Revival Style, from 1837–1843. On the Entrance Front, a battlemented tower dominates. The walls are built with a striated, golden sandstone, which was dug from the quarry that’s immediately below the House. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

After Edward Hussey I acquired Scotney, his family first lived in the Old Castle, but a malaise shrouded the ancient building. Edward Hussey committed suicide there, and his son Edward II survived for only another year. Edward’s widow Anne sensibly flew the coop, and took her surviving son, now named Edward III (why not recycle a perfectly good name, eh?) far away. Edward III, who loved gardens and architecture, never forgot Scotney, and when he came of age, he decided to return ….but not to the Old Castle, which had been tainted. As Edward III worked with his architect Anthony Salvin to build a New House, he rejected suggestions that he demolish the Old Castle. Instead, he began to consider how the Castle might be put to use as a backdrop for gardens. He whittled away at the ancient structure, keeping the oldest parts, and razing interior portions of a 17th century wing. Edward III ‘s idea of a painting-come-to-life inspired his creation of the most romantic-looking vistas within the grounds.

Since my interests tend toward gardens, and to TRULY old houses, we skipped a tour of the New House …after all, an English home built in 1843 must qualify as Merely Modern.

We bypassed the New House, and headed toward the little, arched gateway that’s the Entrance to the Gardens.

Behind the New House, on the Garden Front Terrace, this splendid vista of the Kent countryside unfolds.

A Stone Kitten, on the Garden Front Terrace, with a view back toward the door to the Garden Lobby of the New House.

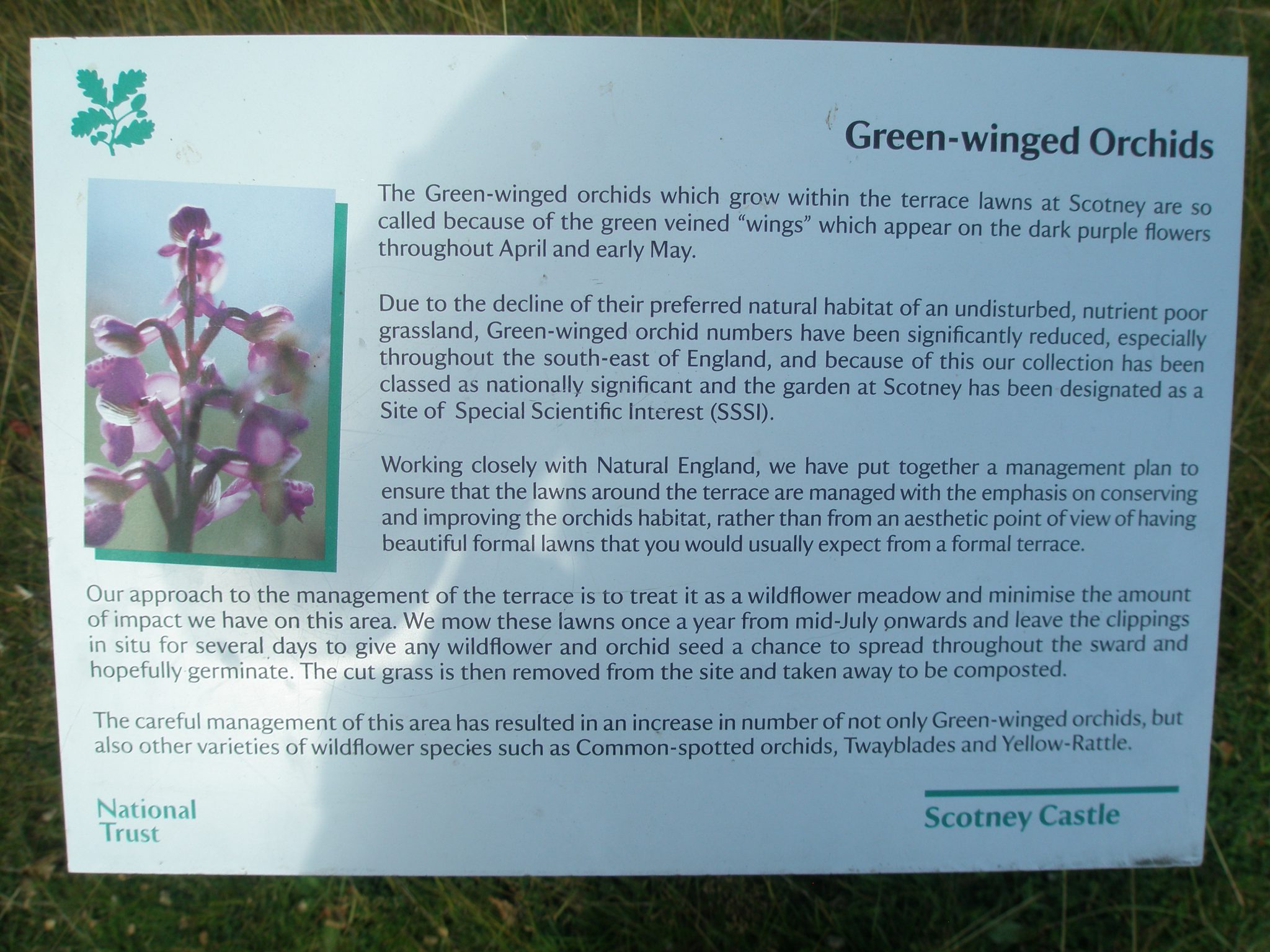

As we left the Orchid Field, I noticed that Amanda had begun to wear an Atypically-Sly-Smile. Hmmm…thought I. What’s up? Our path

ended at a half-circle terrace, and as I glimpsed the ruins of a distant castle, at the foot of a steep slope, my jaw dropped. Amanda grinned even more broadly: she’d just opened the fairy-tale chapter of our day’s adventures.

The light changed constantly, as clouds scudded across the sky. Here’s a closer look at the Bastion View’s balustrade. The Quarry Garden begins directly below the balustrade.

Before we headed downhill, we detoured past an ancient stone Chalice…

…and then inspected the remains of a drovers’ road, which was used for driving livestock on foot, from one place to another. This drovers’ road is ancient, dating back to Medieval times.

We then entered the Quarry Garden. As the Castle’s guidebook notes:

“When stone for the New House was removed and the quarry created, the fossilized remains of a ‘ripple bed’ were uncovered, dating from the Mesozoic geological era, when Scotney was on the shore of a great sea that stretched between England and Belgium. As the ocean tide receded, it left ripples on the sand, which became stone over millions of years.”

As mentioned, sandstone for the New House was quarried on site. The pit left by those excavations created a setting perfectly suited for a dramatic garden, where jagged rocks serve as a backdrop for flowering shrubs and trees, and luxuriant swathes of giant ferns.

The Quarry at Scotney, before it was transformed into a garden. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

By August, the magnolias and azaleas and rhododendrons that fill the Quarry Garden are largely past bloom-time. In the dry heat of late summer, I could only imagine how lush the Quarry had looked, in Springtime.

Huge tree stumps, in the Quarry Garden. In England, Tree Stump Gardens are highly prized. To my American eyes, Stump Gardens are clearly an acquired taste….I’ll work on that.

We left the Quarry Garden, and headed downhill, toward the Old Castle.

We cross the bridge over the Lily-Moat, which surrounds the Old Castle. The moat was formed when the small River Bewl was dammed.

The garden designer Lanning Roper began in 1970 to remake the Old Castle’s herb garden, which surrounds the carved Venetian well-head.

Early morning, in Springtime, the wisteria is in its full glory. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

A peek into the small garden that’s contained inside the walls of the dismantled, 17th century wing of the Old Castle

We passed the gabled Boathouse, which is on the path that wends its way around the stewponds that surround the Isthmus where a sculpture by Henry Moore stands.

THREE PIECE RECLINING FIGURE. 1977. By Henry Moore. Moore donated this piece, in memory of his friend, Christopher Hussey.

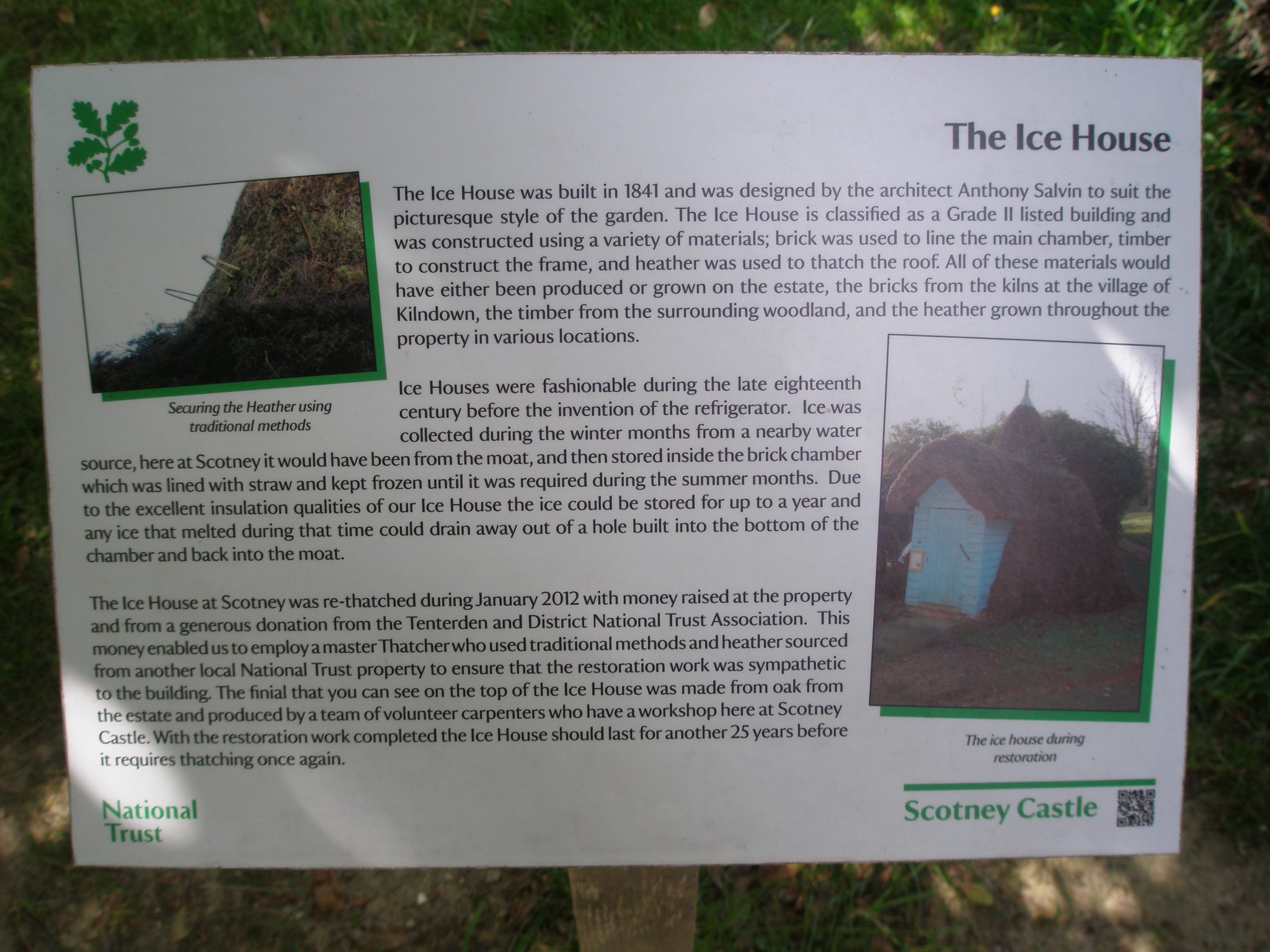

The Ice House was erected in 1841, and its roof is thatched with heather…which smells marvelous. The house hovers over a 13 foot deep pit, which was lined with straw. In wintertime, Ice was cut from the moat, and stored, and kept the Hussey family supplied with ice throughout the summer.

Yes, more Sheep. I do love ’em…but no, I don’t eat lamb chops. These animals graze in a field with endless views of Kent’s countryside in one direction, and spectacular views of Scotney’s gardens in the other direction.

See…the sheep DO have the Best View. This photo was taken from the sheep pasture. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

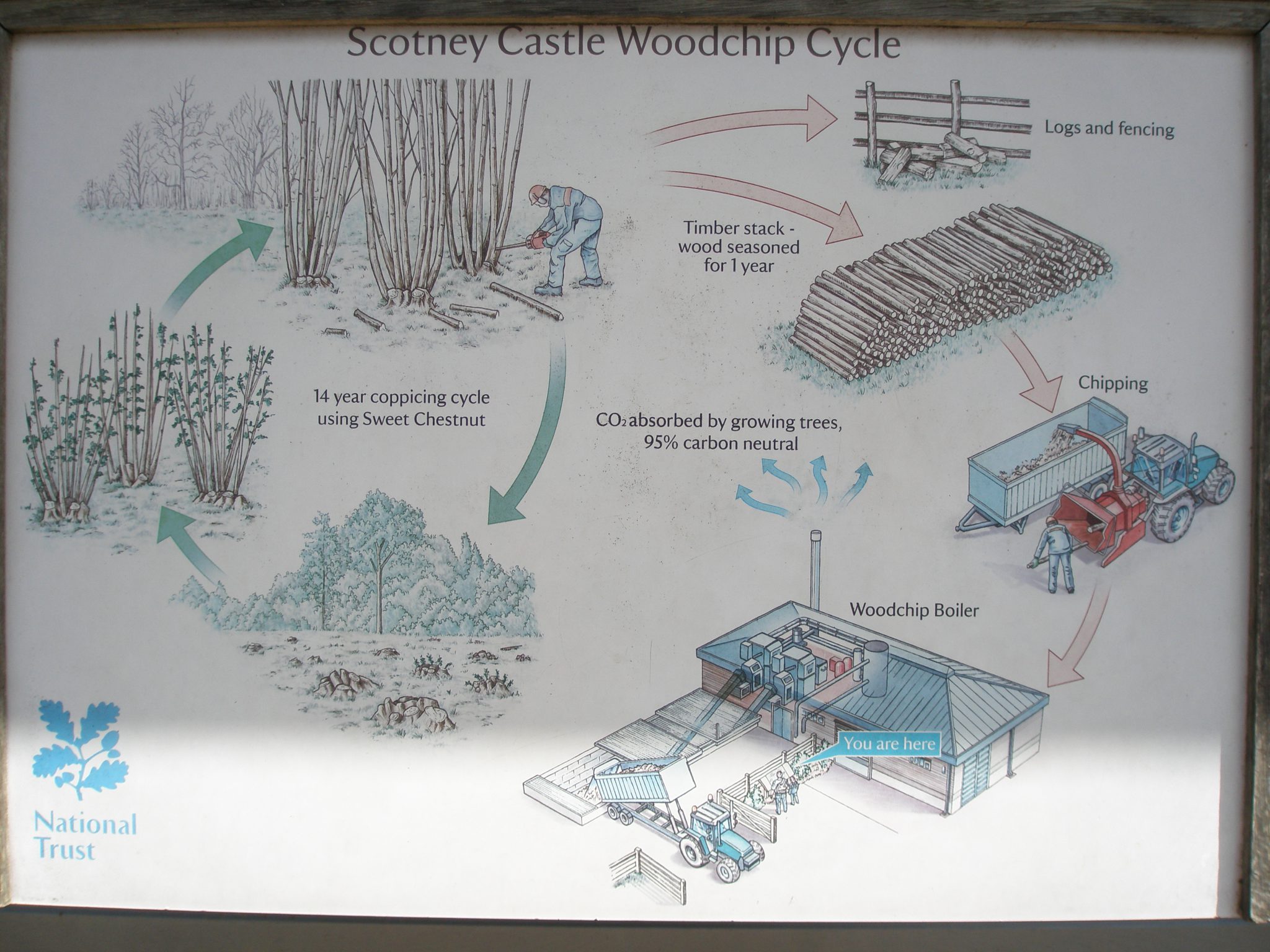

After our garden-amble, I was delighted to learn that Scotney Castle’s grounds contain the National Trust’s only full-fledged hop farm. The Estate is also working toward complete self-sustainability: many of the buildings are already being heated by woodchips which are harvested on site.

I look forward my next visit, when I’ll take time to better explore Scotney’s 770 acres, where wildlife abounds. I’ll admire the Estate’s flocks of sheep; herds of Sussex cattle; badgers; great crested newts (which are Britain’s largest and most threatened newts, for those of you who are salamander-watchers.); fallow and roe deer; and rare, brilliant emerald dragonflies. Ultimately, Scotney Castle’s voluptuous beauties speak for themselves; it’s a tranquil place, a place that soothes thoughts, and quiets speech. Whenever I feel frazzled by this interminable winter that we in the Northeast are currently enduring, I find myself returning to the pictures I took in August at Scotney. Gazing at the Old Castle—mirrored in a lily-filled moat—makes me serene, and I forget about the deep snow that lies, unmelted, outside of my windows.

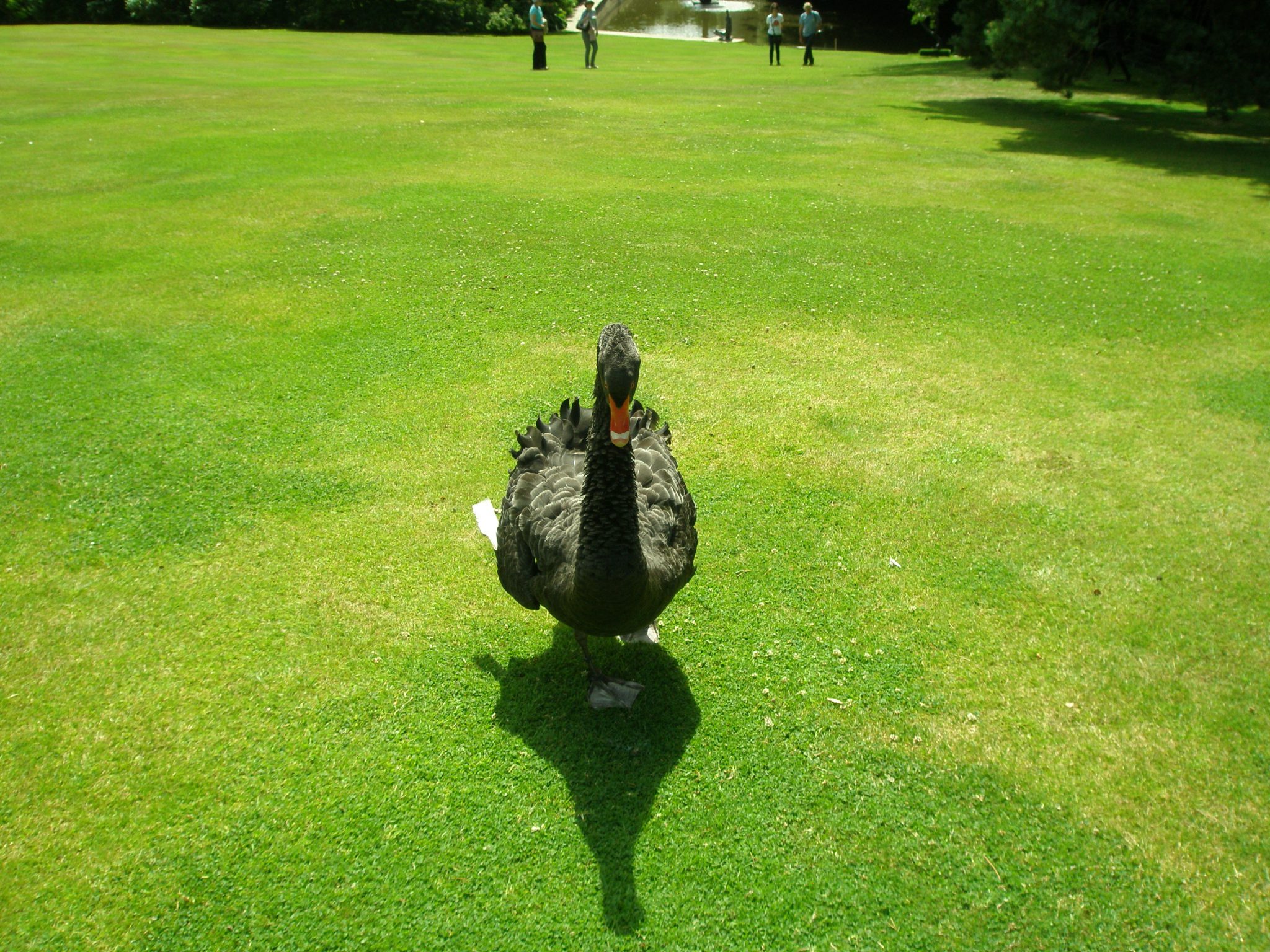

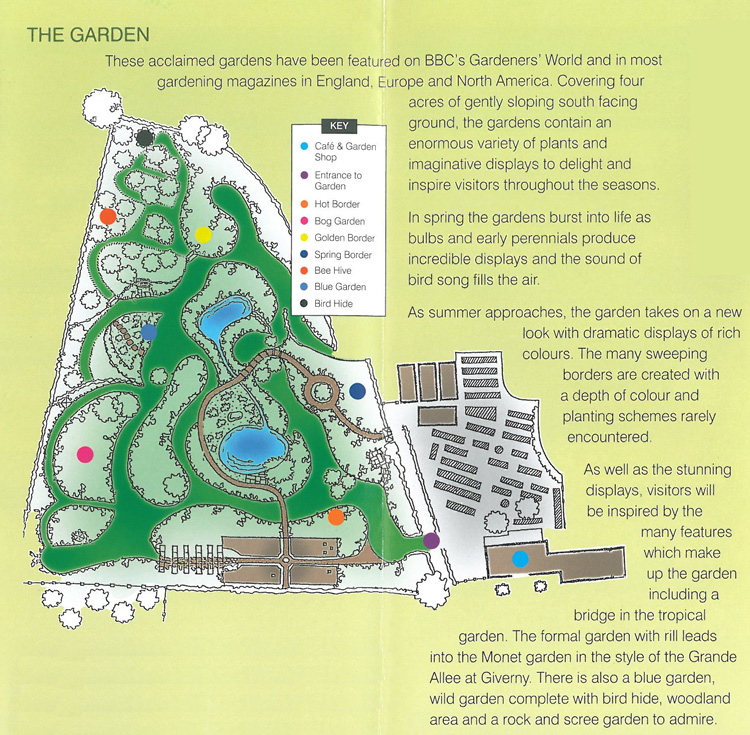

Destination #4: Pashley Manor Gardens

Ticehurst

Near Wadhurst

East Sussex TN5 7HE

Open from April 1st until September 30th

Tuesday through Saturday, 11AM to 5PM

Phone: 01580-200888

Website: www.pashleymanorgardens.com

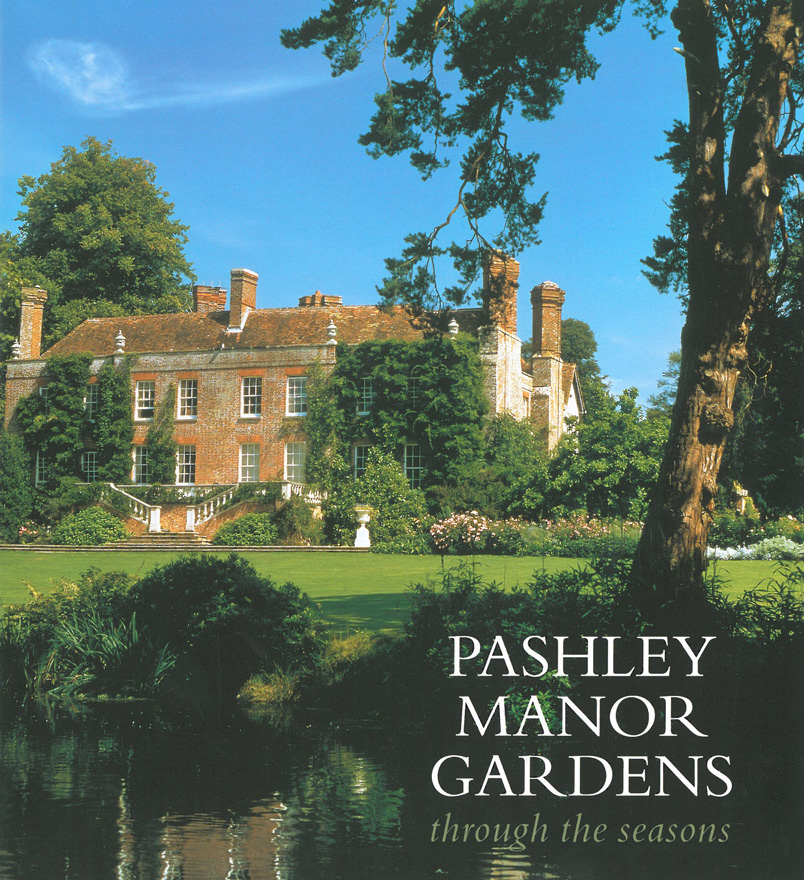

Pashley Manor Gardens, in East Sussex. Impeccably-planted gardens surround a Grade I timber-framed house, which was built in 1550, and enlarged in 1720. The gardens we see today were planted in 1981, on the bones of gardens which were begun in 1720. Image courtesy of Pashley Manor Gardens.

At many of the gardens I visited during my week-long ramble with Amanda and Steve, mention was made of the devastating changes wrought by the Hurricane of 1987. Tales about acres of trees felled, of rocks tumbled, and of soil eroded, were recounted by gardeners at Chartwell, and Great Comp, and Scotney Castle. Pashley Manor, which is just over the Kent border into East Sussex, suffered greatly during the 1987 storms when more than 1000 mature trees were destroyed. But, with her storms, Nature does her weeding, and so the owners of Pashley Manor, whose modestly-scaled borders had only just begun to be planted and expanded in 1981, came to regard their losses as blessings, and the tattered land as a canvas for a garden which could be much improved.

Angela and James Sellick explain: “Previously, the magnificent trees had formed a dense hedge around the garden, but now we have much better views over the surrounding countryside. The old Walled Garden seemed to contain beneath the brambles, weeds, tall grasses and nettles, nothing but tumbledown greenhouses and collapsed cold frames with their attendant shattered remains of flower pots and razor-sharp shards of glass. All these were dominated from outside the wall by large conifers grown for a long-past Christmas market, but fortunately these were blown down by the storm!”

“The series of picturesque and wild linked waterways seemed to constantly empty themselves; we wondered if we had taken on an insurmountable task. Very gradually, with enormous help and encouragement from the eminent landscape architect and author, Anthony du Gard Pasley, an old friend, we have worked our way out from the house, slowly uncovering a garden with great potential which has become one of the most handsome landscapes in Sussex.” In April of 2000, “Pashley was recognized by the Historic Houses Association … when it was voted Garden of the Year as the best HHA garden in the United Kingdom.”

Early afternoon had come, and my stomach was growling. Despite my curiosity about the Gardens, the first order of business had to be LUNCH ( I confess that I become crabby and irrational when I’m hungry ), and so I rejoiced at the deliciousness of the food that was served to us in Pashley’s Garden Room Café.

In retrospect, as I recall the many meals I ate last August in England, I agree with SUSSEX LIFE MAGAZINE, whose food critic declared that Pashley has “arguably the best garden café in the country.” Our salad greens had just been harvested from the vegetable plots we’d strolled through. The zucchini (or Courgettes, as the English call them) on my plate had recently been cut from the vine. As I savored each bite, I could taste how tenderly Pashley’s gardeners had cared for their plants. Revived by veggie garden bounty, Amanda and I began our tour of the 11-acre Estate, where constantly-changing exhibits of whimsical pieces of sculpture add to the light-hearted atmosphere.

At the base of the central path through the Herbaceous Border, this 8-foot-tall Lady exposes a shapely leg. Behind her is a Ha-Ha ditch, which keeps Pashey’s flocks of sheep in their fields, and out of the Gardens

Per the Manor’s Guidebook, when the Pashley sheep are shorn, their fleece is then used as mulch, around the roots of the trees in the orchard. “The fleeces are then pinned down with hazel twigs. This was a traditional method of retaining moisture and preventing weed growth. The lanolin and nitrogen leach from the fleeces as they rot and feed the trees. This ancient method of mulching is also greatly appreciated by birds as it provides nesting material.” And the fruit of Pashley’s sheep is put to further use come winter, when the flower beds are “mulched with tons of Pashley’s own sheep manure.” Learning these things

has only increased my adoration for Sheep!

Another view of the Hot Gardens, in the Herbaceous Border section of the Garden. Image courtesy of Pashley Manor.

We enter the Walled Garden. The Walled Garden was established in 1720 and is historically listed in its own right. During WWII, while the House was a temporary home for soldiers from Canada and Poland, the gardens fell into disrepair.

Every year, for 10 days in the Spring, Pashley Manor holds a Tulip Festival, when over 20,000 blubs–and about 100 different varieties of Tulips–burst into bloom. This photo shows a corner of the Rose Garden, during 2013’s Tulip Festival. Image courtesy of Pashley Manor.

The Potager (aka Kitchen Garden) is opposite the Rose Garden, and also within the Walled Garden. This is where many of the veggies I ate at lunch were grown.

In the Potager, with Pashley’s Head Gardener. I thanked him for the wonderful food he grows. The Rose Garden is in the background.

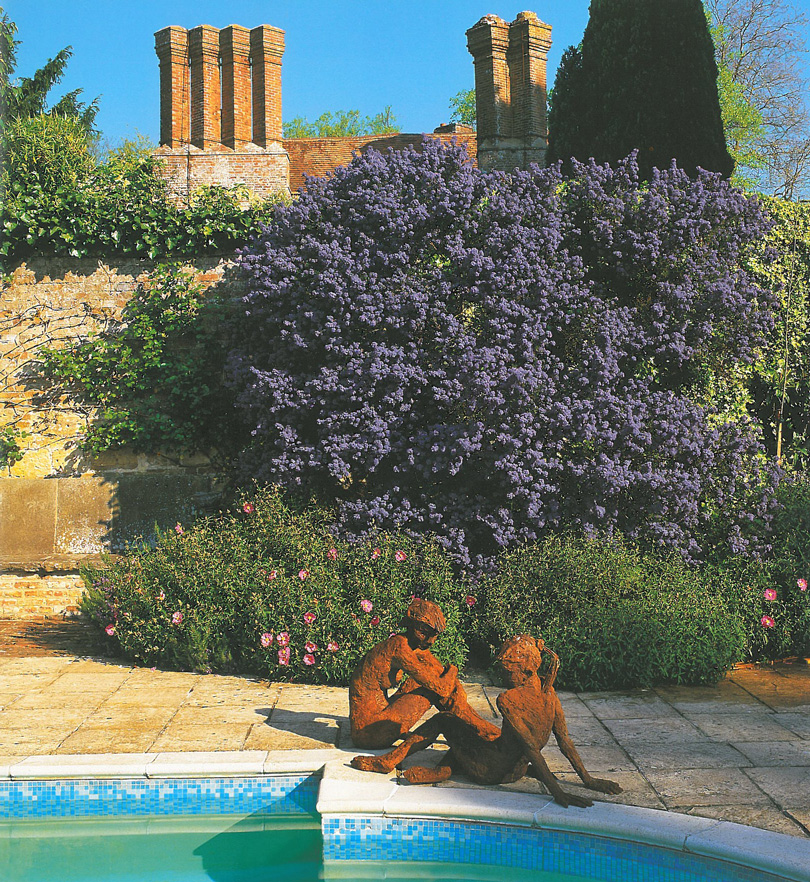

In the Pool Garden, yet another sculpture, this one by Kate Denton. Billowing against the brick of one of the original Elizabethan-era walls is a huge shrub: Ceanothus ‘Puget Blue,’ which is evergreen, and in early summer bursts into bloom with thousands of royal blue flowers. Image courtesy of Pashley Manor.

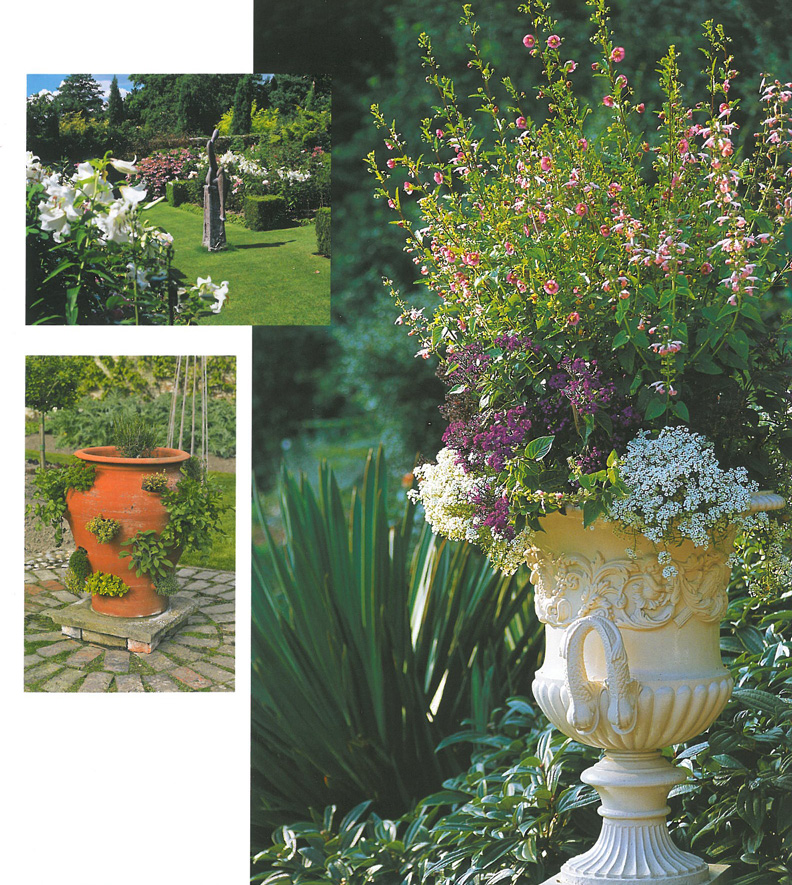

In the largest photo: One of a pair of cast-iron 19th century vases is on the Terrace, filled to overflowing with fragrant summer flowers. Image courtesy of Pashley Manor.

The arched, wrought-iron bridge leads to the Island in the Moat where the original house, built in 1262, once stood.

On the Island: a Classical Temple, and a statue of Anne Boleyn. The Boleyn family owned Pashley in the 16th century, and used it as a hunting lodge.

ANNE BOLEYN, by Philip Jackson. This is one of the sculptures that’s permanently mounted in Pashley’s gardens.

The gardens at Pashley Manor are comprehensibly small, and sweet, and friendly. And the mostly light-hearted sculptures that dot the Estate give the place a good-humored vibe. While the landscapes at Scotney Castle demonstrate gardening, ramped up to highest, Grand-Opera volume, the lovingly-cared for little plots at Pashley Manor show how charming short, light works of gardening at Operetta-level can also be.

Destination #5: Merriments Gardens

Hawkhurst Road

Hurst Green

East Sussex TN19 7RA

Display Gardens open from early April to mid October

Monday through Saturday, 9AM to 5PM

Sunday, 10:30AM to 4:40AM

Phone# 01580-860666

Website: www.merriments.co.uk

Our route between Pashley Manor and Sissinghurst Castle—which would be the final garden-of-note on the day’s itinerary—took us past Merriments, one of England’s most acclaimed and elaborate garden centers. At Merriments, even the most inexperienced gardener can ramp up his gardening-game. After a stroll through the 4-acre display gardens, where color-themed borders, woodland groves, and separate gravel, rock, parterre, and water gardens pique the imagination, one needs only to consult with Merriments’ staff about how to achieve similar results in one’s own backyard. Pots of greenery are produced from Merriments’ nurseries, and planting instructions are provided. And if you’re feeling extra-lazy, Merriments will send their crew of landscapers to your home…PRESTO-CHANGO….Instant Garden-Gratification!

Here are some of my favorite vignettes, from the Merriments gardens.

An elegant Rill, surrounded by grasses. I’d actually like to lift this in its entirety, and transplant it into my New Hampshire garden.

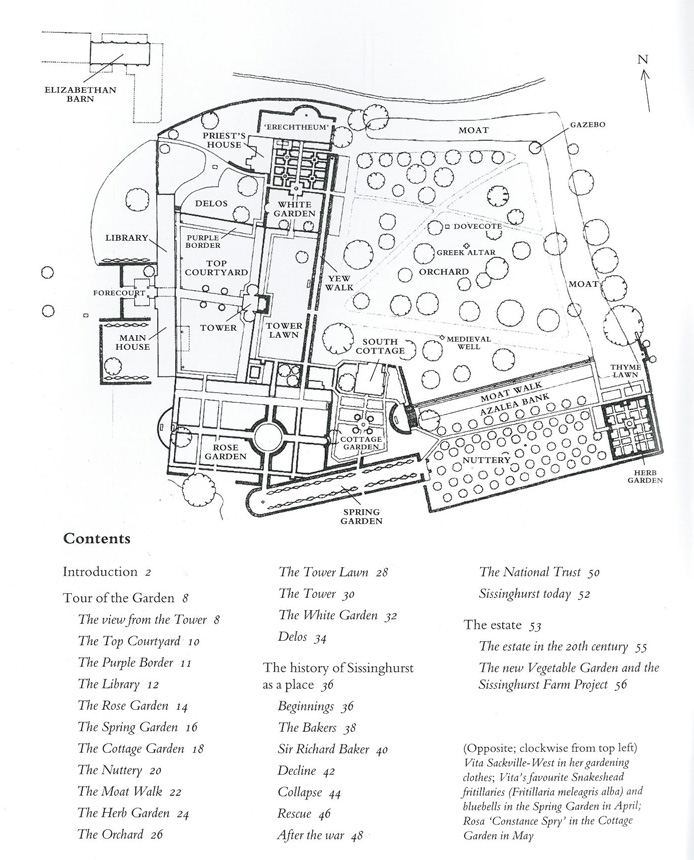

Destination #6: Sissinghurst Castle Garden

Biddenden Road

Near Cranbrook

Kent TN17 2AB

Gardens best seen from April through October

Open Daily, 11AM to 5PM

Phone# 01580-710700

Website: www.nationaltrust.org.uk/sissinghurst-castle/

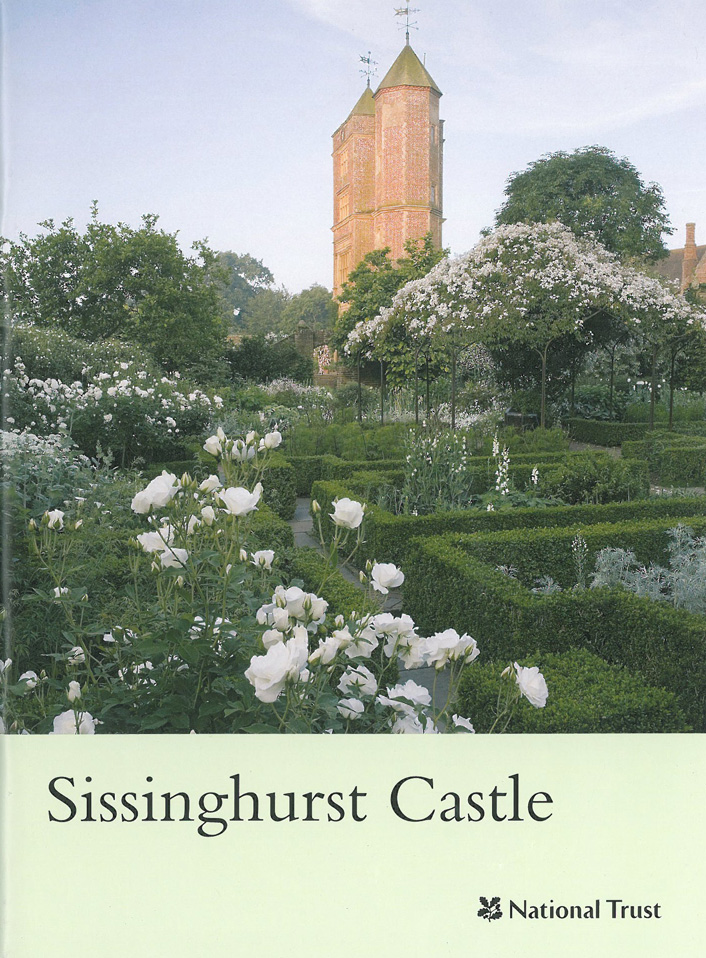

The gardens at Sissinghurst Castle, which were planted in the 1930s, are among the most famous gardens in England. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

Of all the renowned gardens in England, the place whose name is most familiar—even to NON-garden-aficionados—must certainly be Sissinghurst, the home of the writer Vita Sackville-West and her husband, the diplomat Harold Nicolson. First and foremost, “Sissinghurst” conjures up serene visions of boxwood-edged beds of pale-hued flowers, which bloom unendingly around the base of an Elizabethan tower. For years, like any other gardener worth her salt, I’d dreamed of visiting Vita’s White Garden.

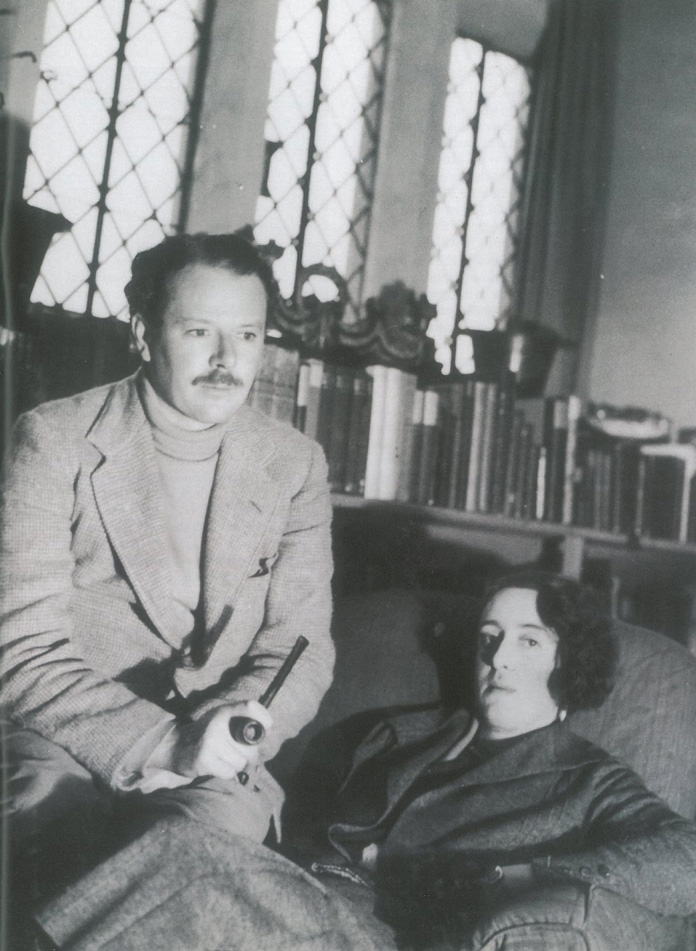

Harold Nicolson (born 1886, died 1968) and Vita Sackville-West (born 1892, died 1962) in the Tower Sitting Room at Sissinghurst Castle, circa 1930. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

As is usually the case in Life: reality falls short of dreaming. Thus far in my garden-questing I’ve found only a few places where reality EXCEEDS dreams. Scotney Castle qualifies for this very-short-list, as do the hillside gardens at Villa d’Este, in Tivoli, just northeast of Rome. I’ve written about Villa d’Este in the past, and will do so again at greater length: I’ve scheduled my third visit to those Italian Renaissance gardens for this coming May, and a long article will appear in late summer. The Chinese-scroll-painting-come-to-life at Innisfree Garden, in Millbrook, New York, which I extolled in “Part One: Hudson River Valley Gardens,” certainly belongs in this rarefied company. And the little-known gardens at Sezincote, in Gloucestershire, where conservatories capped by turquoise onion domes, and parklands dotted with statues of elephants and sacred cows (along with some REAL cows) nestle into Cotswold hills, will also be the centerpiece of a future Diary.

But Sissinghurst is on the verge of being loved to death. Along with the equally-famous gardens at Hidcote — which I visited in September of 2012, and which I wrote about in my Armchair Diary titled “Major Ramblings Across the English Countryside” — Sissinghurst is straining at its seams. Bus-load after coach-load of garden-gawkers tumble onto the grounds for a spot of cream tea, followed by a tower-climb, and then by a trot through the series of modestly-scaled garden “rooms” that Harold Nicolson laid out to hold his wife’s painterly combinations of plants.

Of course, for anyone to whom garden-history matters, paying a call to Sissinghurst IS a must. Just be prepared for the gardens to become periodically inundated by waves of people. You’ll have to queue for your turn to climb the Tower (where traffic jams happen as the steep, winding steps cause out-of-shape visitors to do a lot of staggering and huffing and puffing), and you’ll have to wait patiently to snatch quiet moments on the Lime Walk, and in the Rose, and Herb, Gardens.

My greatest photographic challenge during Tuesday afternoon’s waning hours was to take pictures that did NOT include the same lady in a white sweater who would reappear, like Zelig, around every corner, whenever I’d waited until I thought the coast was clear enough to take an un-peopled shot of the gardens.

Ultimately, I make my own little gardens here in New Hampshire, and then travel the World to learn from my Gardening-Betters, for a single reason. Gardening—and Gardens—calm me….but only when I have the high privilege of spending quiet and nearly-private time in the contemplation of my surroundings. Worldwide fame hasn’t yet robbed Sissinghurst of her beauty, but the tranquility that Vita Sackville-West described in the following passage is no more:

“The heavy gold sunshine enriched the old brick with a kind a patina, and made the tower cast a long shadow across the grass, like the finger of a gigantic sundial veering slowly with the sun. Everything was hushed and drowsy and silent, but for the coo of the white pigeons sitting alone together on the roof…

They climbed the seventy-six steps of her tower and stood on the leaden flat, leaning their elbows on the parapet, and looking out in silence over the fields, the woods, the hop gardens, and the lake down in the hollow from which a faint mist was rising.”

Try to keep that lost tranquility in mind, as our garden tour begins.

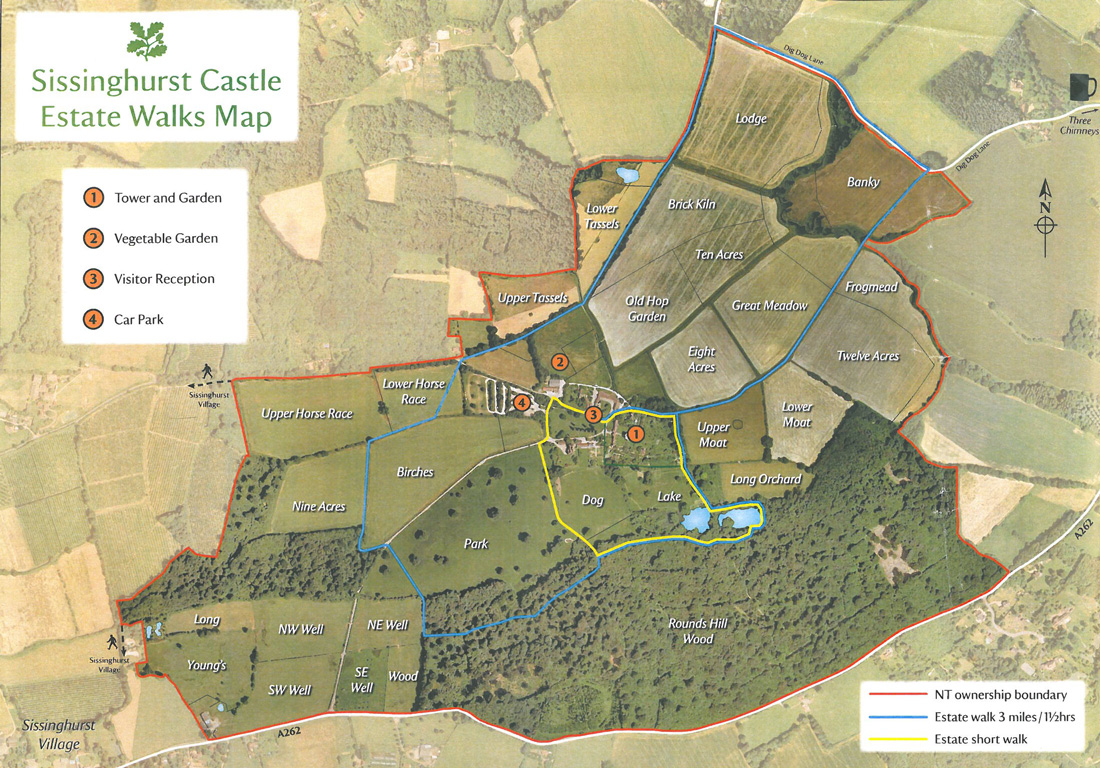

The garden at Sissinghurst sits within some 470 acres of the Kentish Weald. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

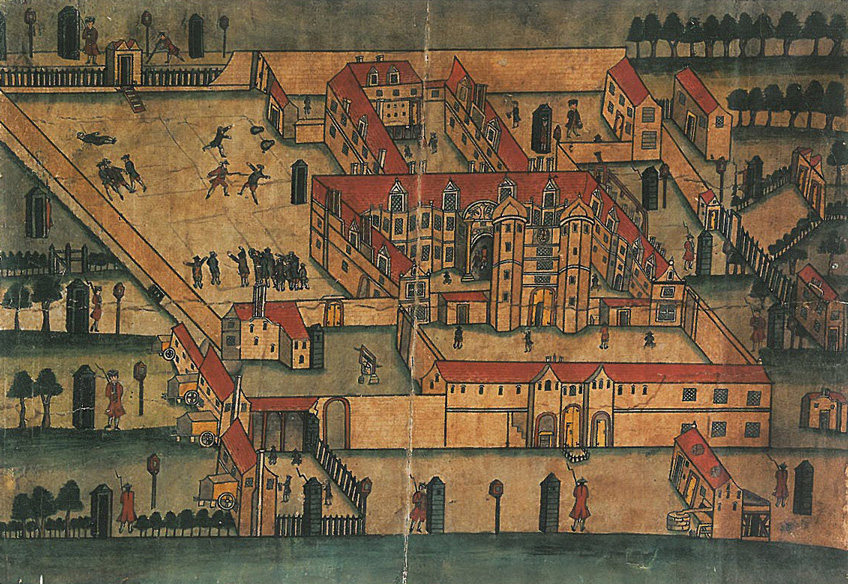

The Castle, which was at one time much larger than the complex that we see today, began to be constructed in the 1530s, when the entrance and long front range were built by Sir John Baker. Eventually, a huge series of enclosed courtyards were in place. During the Seven Years War (1756–63) Sissinghurst Castle was used as a prison camp.

This postcard shows the camp. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

We approach the front range of the Main House. The twin roofs of the Tower–which is a separate structure–are in the distance.

We’re headed toward the tunnel that bisects the Main House. The Top Courtyard, and the Tower are dead ahead.

At the west end of the Rose Garden, a Lutyens Bench settles into an apse-like curve in the clematis-covered wall.

From the Rose Garden, the southern end of the Main House, and the upper stories of the Tower can be seen.

Slightly off-center in the Rose Garden is the Rondel, a circular space enclosed by high hedges. My omnipresent Lady In The White Sweater now makes the only guest appearance that I’ll allow her!

Amanda, by the Rose Garden wall, with a view down the narrow Yew Walk, which extends along the long, Eastern side of the Tower Lawn

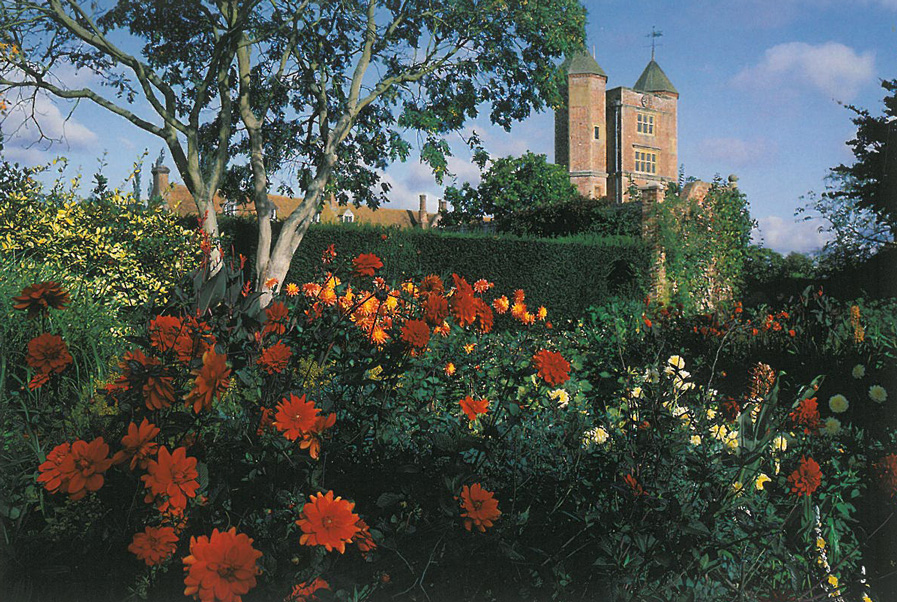

Leaving the Rose Garden, we entered the small Cottage Garden, which is always planted with rich orange, red and yellow flowers.

Mixed Dahlias in the Cottage Garden, with the Tower in the distance. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

After the Cottage Garden, we entered the Lime Walk, in the Spring Garden. Since the 1930s, when Harold Nicolson designed the Lime Walk, the trees have been replaced two times.

The Nuttery is a plantation of Kentish Cobnuts–a variety of Hazelnut. The entire Nuttery is underplanted with drifts of Spring-blooming bulbs. This is a view of The Nuttery, in April. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

At the Eastern end of The Nuttery, a Herb Garden is nearly hidden behind tall yew hedges. We’re on the outside of the Herb Garden.

Between the Herb Garden and the Moat Walk is a Thyme Lawn, first planted in 1946. Sissinghurst’s gardeners say maintaining the Thyme Lawn has always been difficult. When the thyme isn’t flowering, people trample it. Happily, when the thyme is in flower, the Lawn is abuzz with bees….which keeps toes away from the tender plants.

A Byzantine Stone Bowl supported by lions is the centerpiece of the Herb Garden, which was planted in 1933-34.

Detail of tiles in terrace, which are installed with narrow ends up, under the Byzantine Bowl. This same use of tiles–with narrow ends up– can also be seen in the gardens at Hidcote.

We left the Herb Garden, and ambled down the Moat Walk, which is planted with a long bank of Azaleas along one side.

In Springtime, the Moat Walk is abloom with wisteria, azaleas and bluebells. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

At the far corner of The Orchard, where the northern and eastern courses of the Moat meet, Nicolson built a Gazebo, which has windows overlooking the water, and the distant fields.

At the Northwestern edge of The Orchard, a narrow opening in the Yew Walk hedge leads us into the White Garden.

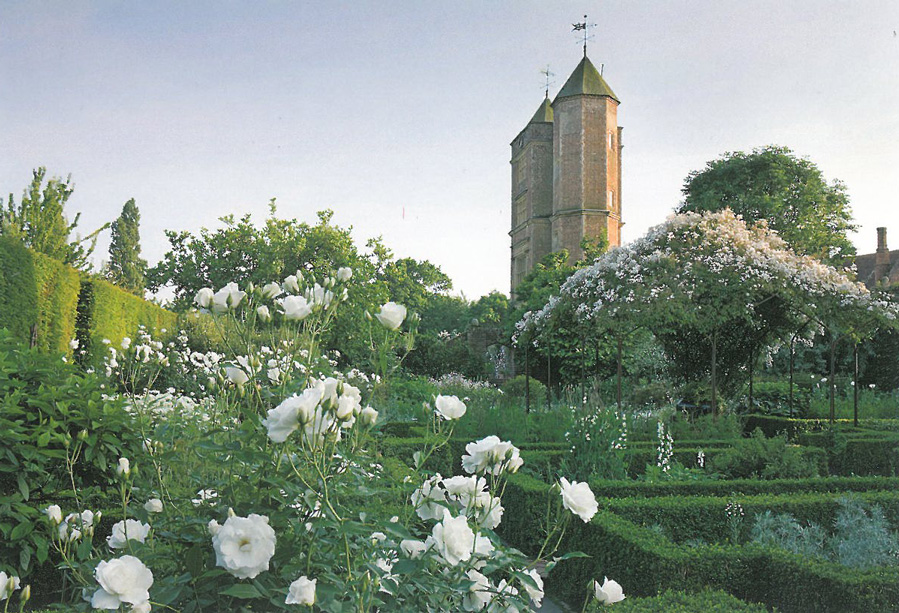

The White Garden was the last of the gardens at Sissinghurst to receive its identity. Until 1950, it had been filled with a miscellaneous collection of flowers, in mixed colors. It was Vita’s idea to plant a garden where white flowers would glow in the moonlight.

Ideally, the White Garden should look like this, with white climbing roses covering the Pergola. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

To the West of the White Garden is the Delos, which is planted as a carpet of woodland flowers. The Delos was designed in the mid-1990s by head gardener Sarah Cook, long after Vita and Harold had exited the scene. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

We leave the White Garden through the Bishop’s Gate, then turn right, and head toward the Top Courtyard’s Purple Border.

The Purple Border extends along the Northern edge of the Top Courtyard. The Library Wing of the Main House is directly ahead.

FINALLY….it was time for us to climb The Tower. This is The Tower, when the mobs have gone home. As you can see, the lawn in the Top Courtyard is precisely mowed, in a diagonal pattern–to conceal the fact that the Courtyard isn’t perfectly rectangular–and in double width, to make a bolder impact, when viewed from above. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

Vita Sackville-West, after WWII, on the Tower Steps, with Rollo. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

View through the Tower Arch, toward an opening in the Yew Walk. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

Vita in her Workroom, in the Tower. The Tower was essentially Vita’s domain, from which she could survey all of the Gardens.

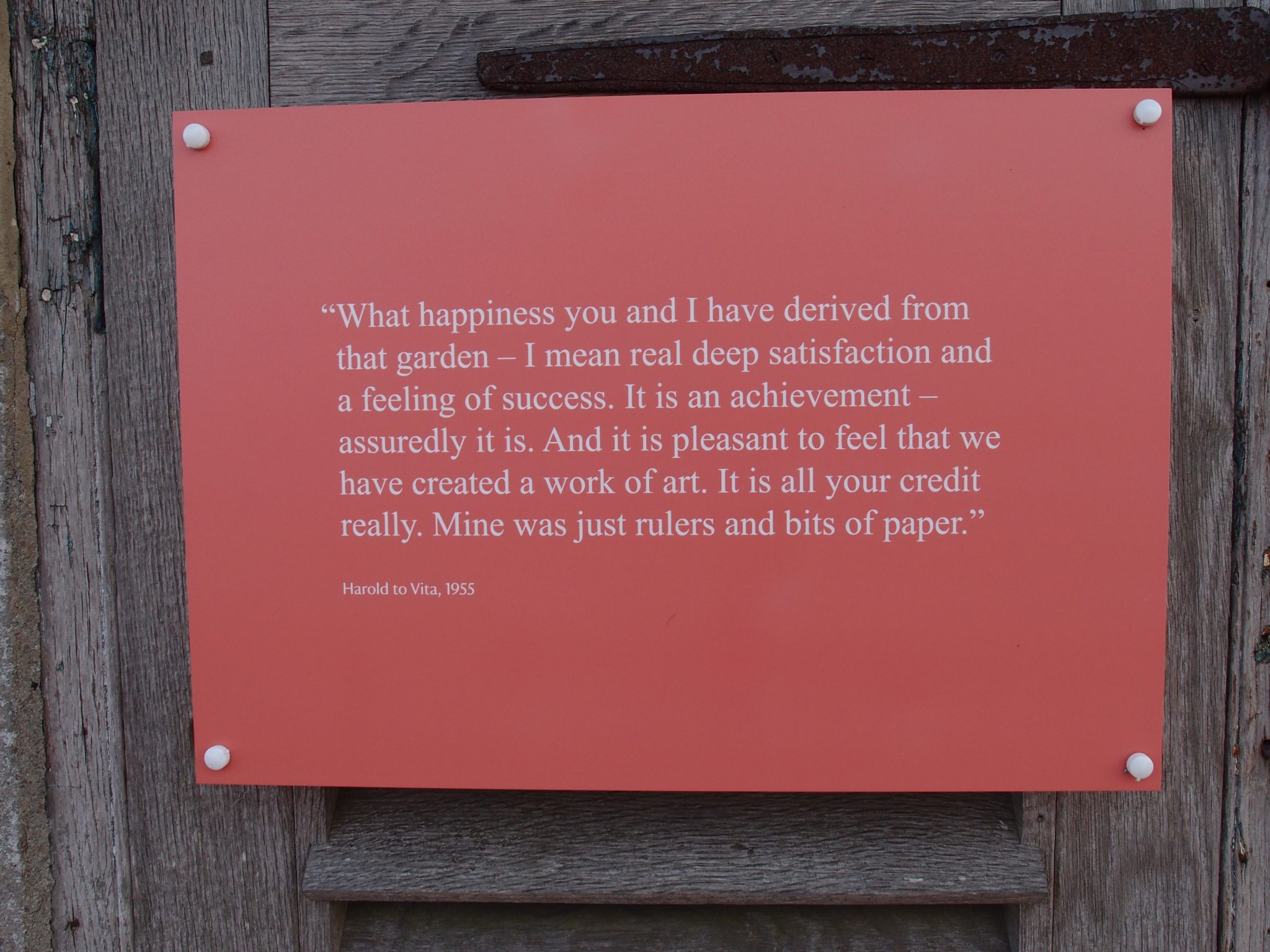

This sign is displayed on the Tower roof. Harold was underplaying his very considerable role in the making of the Gardens.

Finally, as the sun grew lower in the sky, and the crowds dispersed, we’d climbed to the roof of the Tower! From on high, Harold Nicolson’s orderly garden-layout revealed itself.

Here are my best photos of Sissinghurst, which I’ve saved for last. Beginning by looking due North, I began to take a series of pictures, moving in a clockwise direction.

Looking North. The White Garden. Just to the right of the high hedge is a Boathouse, which is placed on the Northwest corner of the Orchard, at the end of the Moat.

Looking Northeast. The Orchard, with the Gazebo at the farthest corner. The tall, double hedges of the Yew Walk are directly below the Tower.

Looking Southeast. The Orchard, with the South Cottage to the right. The Yew Walk is directly below.

Looking further to the Southeast. The South Cottage with the Cottage Garden, and then the Lime Walk.

Looking South. The south end of the Tower Lawn is at the base of the Tower. Beyond that are the circular hedges of The Rondel, and then the trees of the Lime Walk.

Looking Southwest. The western-most end of the Rose Garden, with the southern wing of the Main House, to the right.

Looking Northwest. Past the front range of the Main House, which contains the Library at the northern end, is a complex of Oast Houses.

Looking further to the Northwest. The Purple Border is directly below. Behind the tall brick wall is the Delos, the wild, woodland garden. To the right of the Delos is the Priest’s House. Farther to the left is the Elizabethan Barn.

We rejuvenated ourselves with strong tea and sweet scones, and then took a last look at the beautiful countryside…framed by this arch in the Elizabethan Barn.

This is the image of Sissinghurst I’ll most fondly remember…

My Tower-top view of the Rose Garden’s Rondel, taken late in the afternoon, after the crowds had gone away.

….Harold’s sure-handed geometries hold sway. The late afternoon light becomes golden, and shadows begin to stretch themselves across the carefully-mown checkerboard patterns in the lawns. On the Tower roof then…for me, for a moment…the drowsy hush of her gardens that Vita had so loved had returned.

The private lives of the creators of the gardens at Sissinghurst were complex, to say the least. Hundreds of thousands of words have been spent explaining Vita and Harold’s unusual and fraught…and yet enduring…partnership. If you’re curious about them, the best resource is their son Nigel’s astonishing biography of his parents, “Portrait of a Marriage: Vita Sackville-West and Harold Nicolson.”

With this article, we’ve completed 60 percent of our Kent-adventures.

In Kent-#4 we’ll visit Christopher Lloyd’s anarchic but gorgeous garden at Great Dixter. We’ll walk up cobbled streets in the ancient, coastal town of Rye. We’ll drive across the forlorn expanses of Romney Marsh. We’ll marvel at

Derek Jarman’s anarchic but gorgeous garden on the shingle beach at Dungeness. (Yes…there’s a theme here: next time around we’ll see the creations of two of the Bad Boys of the Gardening World.) And we’ll explore the oldest rooms in Leeds Castle, another moat-encircled jewel.

Derek Jarman’s garden at Prospect Cottage, on the shingle beach at Dungeness. This image courtesy of garden designer, Anne Guy.

Copyright 2014. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express &

written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

4 Responses to Part Three. Rambling Through the Gardens & Estates of Kent, England.