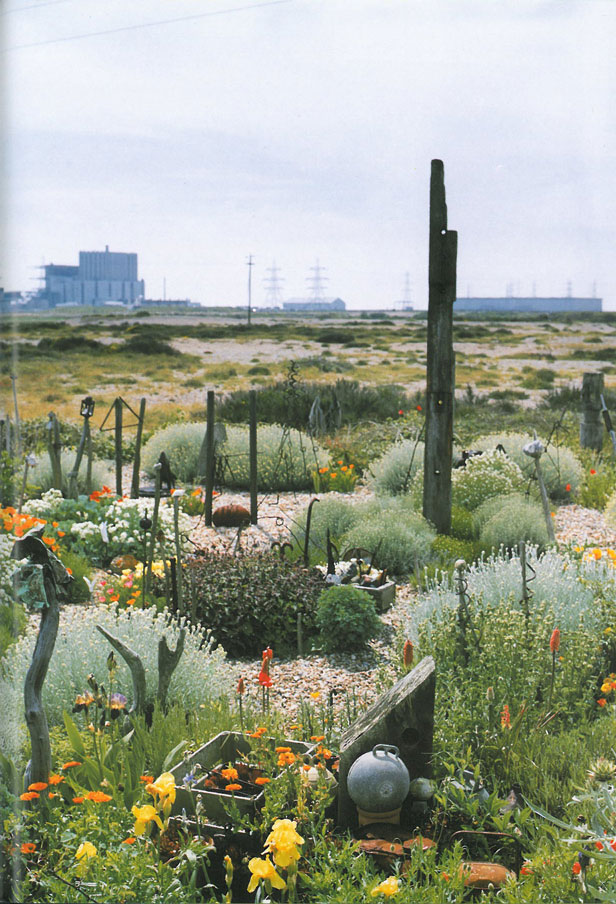

The British film-maker, Derek Jarman, created a tiny, breath-takingly beautiful garden in the inhospitable environment around Prospect Cottage, his home on the shingle beach at Dungeness. Photo courtesy of garden designer, Anne Guy.

www.anneguygardendesigns.co.uk

March 2014. Behind the making of every garden there’s a Story. But, interesting stories alone don’t make for interesting gardens. Only in those rare instances when a compelling story is joined with idiosyncratic inspiration, and then honed by deep design expertise, does a world-class garden spring forth.

Although it’s a rare bird who can create a fine garden, the rest of us don’t need formal training in landscape architecture in order to recognize that a garden IS indeed fine. All a garden-goer needs to do is to pay attention: Phone OFF! Senses OPEN! When a garden’s elements work in concert to satisfy us completely — when what we see, and hear, and smell, and touch and taste seem of a piece — we know we’re on a speck of soil where, for at least a little while, there’s harmony between our animal and spiritual selves, and Mother Nature.

All of the significant gardens that I’ve written about over the past several years have begun as playgrounds for the very rich. But Derek Jarman’s tiny plot on Kent’s barren, southern seashore — which during his truncated lifespan had already gained renown among garden-lovers — shows us how modest means, combined with clear poetic vision, horticultural-smarts, and an endless supply of beach-rock, CAN result in a world-class garden.

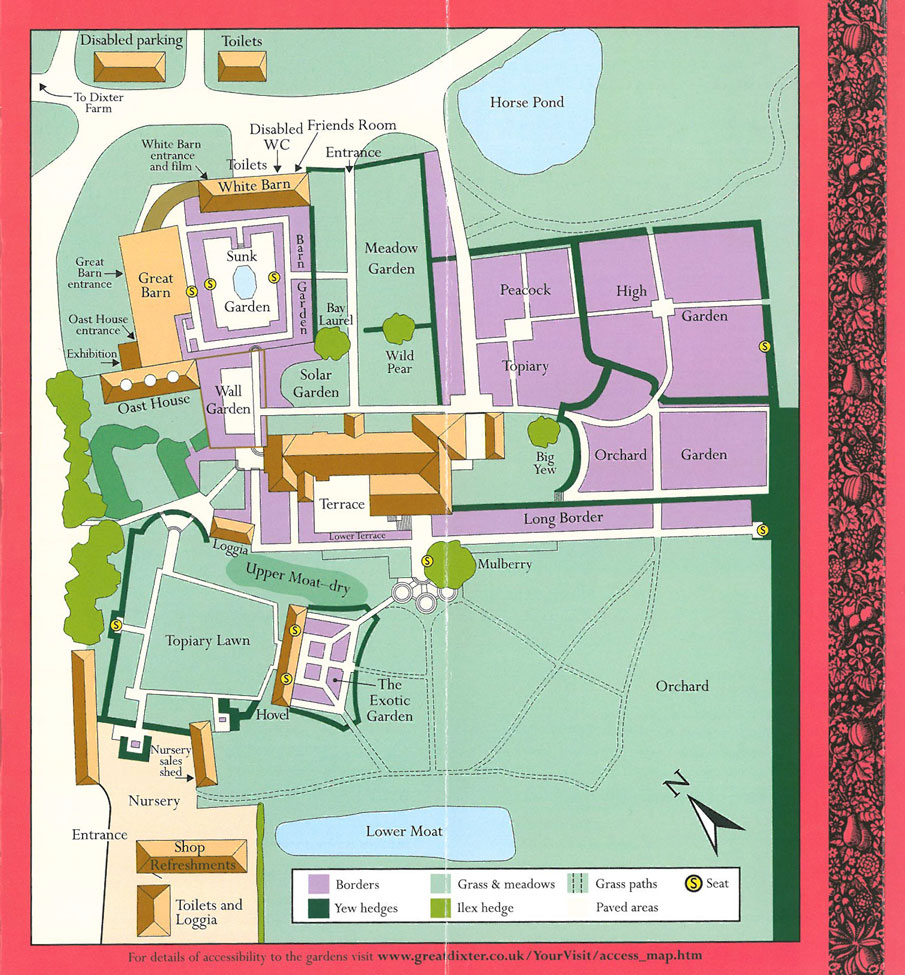

On August 7, 2013, day four of Kent-Exploring with my wonderful Blue Badge Guide Amanda Hutchinson ( www.southeasttourguides.co.uk ) and our Mercedes-Master Steve Parry ( www.snccars.co.uk ) , we traveled to Rye, an ancient seaside town, and to Leeds Castle, yet another romantic, moated fortress. We also we visited a couple of hugely influential English gardens, which represent opposite poles of horticultural showing-off, as practiced by two of the Bad Boys on the English gardening scene….both of them gentlemen who let it be known how little they cared about the conventional methods of planting gardens. Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage is haiku: a spare little plot that shows how driftwood and stone and rusted iron can be transformed into eloquent backdrops for scrappy, beach-tolerant plants. Christopher Lloyd’s Great Dixter is epic: a sprawling demonstration of one plantsman’s passionate determination to make gardens that included all of the plants he loved—regardless of color, texture, scale, or native habitat. Join me now, as our Kent-travels continue:

Destination #1: Great Dixter House & Gardens Great Dixter Drive Northiam Near Rye East Sussex TN31 6PH Open from April through October, Tuesday through Sunday, 11AM—5PM Telephone: 01797-252878 Website: www.greatdixter.co.uk

Christopher Lloyd’s gardens at Great Dixter surround his House, a rambling structure that grew larger, over the centuries. The original structure, built in the mid 15th century, was expanded when an early 16th century yeoman’s house from a nearby town was moved onto the site.

In 1912, the architect Edwin Lutyens was hired by Christopher Lloyd’s

father, Nathaniel Lloyd. Lutyens restored and further expanded the house, and, more importantly, laid out terraces and walls and paths which provided the framework for the gardens around the House which today’s visitors to Great Dixter continue to enjoy. Image courtesy of Great Dixter Charitable Trust

For students of 20th century garden-history, the gardens at Great Dixter are equal in fame to those at nearby Sissinghurst. Just as Vita Sackville-West’s prolific writing about her gardens had made them known to the world, so had Christopher Lloyd’s decades of book and article writing about Great Dixter garnered legions of fans. Having on the previous afternoon braved the coach-mobs at Sissinghurst, I anticipated equally crowded conditions at our morning’s first stop, and so approached Great Dixter in a quietly resigned frame of mind. Silly me…. Amanda had arranged for us to arrive at Great Dixter prior to opening time, and thus well before the herds of other garden-tourists would be tumbling out of their busses. And the iffy weather was also on our side. Heavily-clouded skies, which looked as if they were considering dumping serious wetness, would discourage all but the most dedicated of garden-trompers.

….always nice to have a sign declaring “You Are Here!” Having cleared THAT up, we began our explorations of Great Dixter’s gardens.

Map in hand (you’ll have noticed that I do love my maps), Amanda and I entered the gardens, where planted beds still adhere to the framework established in 1912 by Edwin Lutyens. The contents of those various sections of the gardens are MUCH changed since that time. Christopher Lloyd once said: “I couldn’t DESIGN a garden. I just go along and CARP!” We’re about to see what his carping yielded…

My first view of the Meadow Garden, alongside the

walk toward the front of the House. Christopher Lloyd’s mother, Daisy,

taught him how to garden, and instilled in him her love of meadow gardening, in particular.

As Christopher Lloyd explains, in his GUIDE TO GREAT DIXTER: “Your first sight, on entering the front gate, is of two areas of rough grass, either side of the path to the house. These, and a number of other, similar areas scattered through the garden, bear witness to my mother’s love of this kind of meadow gardening. They are not just plots of grass that we gave up mowing for lack of labour; but were intended from the first.” The meadows “contain a rich assortment of plants that enjoy growing in turf and the grass is not cut until all its contents have completed ripening and shedding their seed. The poorer the soil, the richer the tapestry.”

The seasons unfold, and various flowers emerge from under the turf. Thousands of wild daffodils, and snakeshead fritillaries burst into bloom. Early purple, green winged, twayblade, and spotted orchids emerge. Tall spikes of blue camassia sway in the wind.

Christopher Lloyd died in 2006, at the ripe age of 84. Per his obituary in THE GUARDIAN: “One of six children, Lloyd was born at Great Dixter, into a strictly-run household, where no smoking or drinking was permitted. His father, Nathaniel Lloyd, came from a comfortably off middle-class family in Manchester and his mother, Daisy Field, was reputedly a descendant of Oliver Cromwell. Nathaniel had bought Great Dixter in 1910, and commissioned Edwin Lutyens to restore and add to its 15th century buildings. Lutyens also set out the framework of the garden as an array of formal spaces, which still exist today. Nathaniel died in 1933, leaving the 450-acre estate to his formidable widow.” In 1954, Lloyd, who had been working as an assistant lecturer in science and botany at Wye College, returned to the family home. “He started a nursery, specializing in clematis and uncommon plants. Sharing their enthusiasm for gardening, mother and son continued to develop the gardens and encourage visitors until Daisy died in 1972. The house and garden then became the property of Christopher and his niece Olivia.”

“In 1957, after experimenting with Dixter’s long border, Christopher wrote his first book, THE MIXED BORDER, propounding the revolutionary idea of combining shrubbery and herbaceous border.” Then followed many more books, as Lloyd also produced a 42-year-long run of weekly articles for COUNTRY LIFE.

“As a result of Christopher’s writing, Great Dixter is the most documented of gardens, its most celebrated feature being the immense mixed border, measuring 210 feet long by 15 deep, planned for midsummer, but in reality extending from April to October. More recently, bored by his celebrated but diseased rose garden, he announced that roses were ‘miserable and unsatisfactory shrubs.’ Encouraged by his protégé and head gardener Fergus Garrett—but to the alarm of gardening cognoscenti—he created a tropical garden. Occasionally referred to as ‘the ill-tempered gardener,’ Christopher did not suffer fools gladly.”

As Polly Pattullo added to that remembrance: “He enjoyed communicating his radical views. On a March visit, he pointed out a startling display of pale blue and baby pink hyacinths under a bush of orange-stemmed spiraea; he chuckled and told us that his old friend Beth Chatto had commented that this colour scheme ‘jarred.’ But Christopher’s aim was not to shock—he wanted to stimulate the sometimes precious world of gardening.”

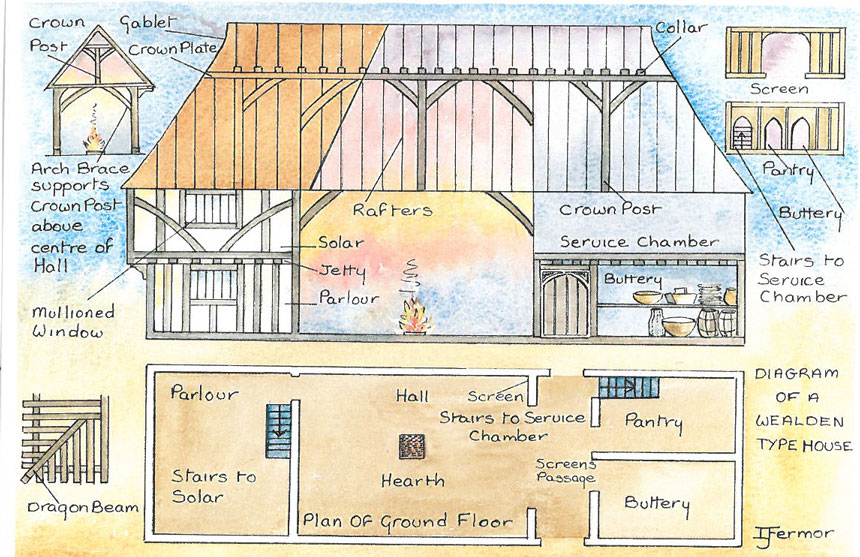

To the right of the front entry porch is the Great Hall, which has been restored to look very much as it did when it was built in the mid 15th century. The Hall is one of the largest surviving timber-framed halls in England (measuring 40 feet by 25 feet, and 31 feet high). Image courtesy of Great Dixter Charitable Trust.

A cross-section of a building similar to Great Dixter’s ancient Hall. Image courtesy of Great Dixter Charitable Trust.

In the Solar Garden, by the front of the House, a virtuoso display of the use of annual plants, in this case the humble snapdragon, took my breath away. Per Lloyd: “Annuals and tender bedding plants feature prominently throughout the gardens, but they are not often seen in obvious beds of their own cut off from other features. For example, the largest single area of bedding, next to the old bay tree facing the front of the house is backed by a swathe of white Japanese anemones. They flower from late July to mid-October and provide a suitable backdrop for any coloured bedding I choose to plant in front of them, and this varies with every year. Bedding allows you the swiftest opportunities to experiment, and, if it goes wrong, the defects can quickly be obliterated. This bedding is changed twice or even three times a year.”

The gorgeous crescent of crimson and salmon colored snapdragons, in the Solar Garden, with the Oast House, and the Great Barn to the rear.

Lloyd’s GUIDEBOOK describes his Barn and Oast House: “The barn, with its long, tiled roof reaching quite near to ground level, on the garden side, is characteristic of this part of the Weald. It is supposed to be contemporary with Dixter itself. The oast house, with its three kilns, was built about 1890, and hops from the nearby hop garden were dried in it up to 1939.”

Lloyd’s chatty GUIDEBOOK continues: “The Sunk Garden is surrounded by the Barn Garden. My father was responsible for the design and making of the Sunk Garden, originally lawn, then dug up for vegetables during the First World War; after which my father said ‘Now we can play.’ The Barn Garden has the merit of giving a good view across the Sunk Garden, wherever you may be standing. About half the floor of the Sunk Garden is deliberately kept clear of plants, by the use of herbicides.” SO….shameless use of herbicides! My natural-gardening-self recoiled, but was slightly reassured by Lloyd’s assertion that, nevertheless, “the gardens are a veritable bird sanctuary, rich in suitable nesting sites for many species.”

In the Sunk Garden, luxuriant blooms….from some of the few rose bushes that Lloyd allowed to remain at Great Dixter.

The view from the southern end of the Sunk Garden, into the Wall Garden. Note Lutyen’s careful detailing of the arch and steps.

Lloyd described his Wall Garden as “a rectangle of walls which cause destructive wind eddies and vortices. The protection they afford is largely in the imagination.”

Within the Wall Garden is a terrace, with a pebble mosaic of Christopher Lloyd’s two beloved dachshunds, Dahlia and Canna. The stones for Canna’s eye and nose were acquired from Derek Jarman’s rock-garden, at Prospect Cottage, in Dungeness.

Detail of the house. Note that even the ROOF provides a place for plants to root themselves. This portion of the house was added by Edwin Lutyens in 1912.

Beginning in 1912, Lutyens instructed that yew topiaries be planted in several areas of the garden. And yew hedges were also established. Per Lloyd: “Most of the garden design was by Lutyens; it always seems fluid, never stodgy. The yew hedges are sometimes curved, making a change from straight lines.”

The plantings in the Peacock Topiary Garden are so dense that the towering topiaries become nearly invisible.

While in the Peacock Topiary Garden I began to understand how radical Lloyd’s approach to gardening was. Having inherited a well-established and tidy set of formal gardens, all nicely ornamented with by-that-time mature topiaries, he began to inject chaos into those serene environments. Shrubs and annuals and perennials and biennials jostle for position. Towering, spiky mulleins, clearly self-sown (and which I ruthlessly extract from my own gardens), block paths that have been made intentionally narrow. This part of the garden is a place that enforces the touching and sniffing of plants, which caress each passer-by. Trailing nasturtiums wind themselves up and through dense growths of yew. The positioning of the plants around the topiaries seems willy-nilly, but, upon further study, harmonies—or contrasts—of color and texture and scale become apparent. There’s clearly INTENTION at work here: we’re seeing the fruits of an extremely restless-gardening-mind. These horticultural acrobatics provide much food for thought, but they’re often exhausting. Nope….don’t visit Great Dixter if you’re in need of relaxation!

A more Dramatic View, from the Peacock Topiary Garden. Image courtesy of Great Dixter Charitable Trust.

A central path through the Peacock Topiary Garden leads toward an arch, which serves as entry to the High Garden.

Paths in the Peacock Topiary Garden are intentionally narrow. One brushes up against everything that grows there.

The High Garden , and then the Vegetable Garden, are the most utilitarian parts of Great Dixter. Compost is aged here, and stock for the on-site Nursery is grown, along with multitudes of vegetables. Espaliered fruit trees flank flower borders.

In the High Garden, compost piles. This stuff is the Black Gold of which serious gardeners dream. Notice that the compost piles also serve as homes for vigorous squash plants.

Taking a last look over our shoulders at the Peacock Topiary Garden, we’re about to enter the Long Border, at its almost-mid-point.

Per Lloyd: “Dixter’s a high maintenance garden; I make no bones about that. It is effort that brings reward. There are many borders and much work goes into them. Labour saving ground cover is not for me. It you see ground cover, it’s there because, first and foremost, I like it. The borders are mixed, not herbaceous. I see no point in segregating plants of differing habit or habits. They can all help one another.”

“I have no segregated colour schemes. In fact, I take it as a challenge to combine every sort of colour effectively. I have a constant awareness of colour and of what I am doing. Many plants in this garden are self-sown and they often provide me with excellent ideas. But I do also have some of my own!”

“Fergus Garret and I work hand in glove and he is as fertile in making suggestions for change and improvement as I am.”

“The Long Border’s season of interest is principally aimed at a mid-June to mid-August period, but in fact extends from April to October. It is my belief that no gaps, showing bare earth, should be visible from late May on. The effect should be a closely-woven tapestry. I do not at all mind bringing some tall plants to the border’s front, so long as an open texture allows the eye to see past them. Conversely, channels of low growth can be allowed, at times, to run to the back of the border. For all the work that goes into it, I want the border to look exuberant and uncontrived. Self-sowers, like verbascums and Verbena bonariensis, help toward this.”

A bamboo grove has recently been planted in the Orchard….let’s see how long it is until the Orchard has become a bamboo forest.

The immense Long Border extends along the northern edge of the Orchard. This mixed border, which measures 15 feet deep by 210 feet long, is the garden’s most celebrated and labor-intensive feature.

In the Long Border, as everywhere else at Great Dixter, tall plants are often placed at the front of garden beds, thus breaking the conventional rules of what to plant, and where.

At the house-end of the Long Border, Edwin Lutyens built a series of circular steps and terraces, which lead down to the Orchard.

A view up Lutyens’ Circular Steps. Atop the dry stone wall, Red Valerian flowers keep things colorful. Image courtesy of Great Dixter Charitable Trust.

From the Circular Steps, one path leads toward the Exotic Garden (where Lutyens originally planted a rose garden).

Paths are mown through the tall grass of the Orchard. This entire area is underplanted with Spring-blooming flower bulbs.

We enter the Exotic Garden, an area which Lutyens had designed as a formal, rose garden. When disease overtook the roses, Christopher Lloyd and his head gardener Fergus Garrett enthusiastically dug up the ailing bushes, and replaced them with tropical plants, many of which actually survive England’s winters.

Of all Christopher Lloyd and Fergus Garrett’s changes to the gardens at Great Dixter, none gave them as much pleasure as their erasure of the formal rose gardens that had been designed by Lutyens. Lloyd wrote: “We created a late summer- to-autumn garden for tropical effect, though many of the best foliage plants are quite hardy. This has been a lot of fun. For colour, we are mainly using dahlias and cannas. There is a haze of purple from purple self-sowing Verbena bonariensis. A white, August-September flowering shrub, Escallonia bifida, is usually besieged by butterflies. The banana, Musa basjoo, is a hardy Japanese species.”

The loopy but charming juxtaposition of giant tropical plants, with the 16th century wing of the house.

I kept thinking that the Exotic Garden really needed to have some wild parrots living among the banana plants.

Along the edge of the Exotic Garden, masses of annual flowers seem to extend up onto the roof of the Hovel.

This is what the Topiary Lawn looked like in 1918, when Christopher Lloyd’s mother Daisy presided over a much-tidier Topiary World. Image courtesy of Great Dixter Charitable Trust.

Lloyd called the yew topiaries on the Topiary Lawn his “coffee-pots.” The Lawn—–now more a meadow—is enclosed by high hedges of olive green holm oak, and by a line of closely planted ash trees.

A path mown through the Topiary Lawn, toward a large bench. The roof of the Nursery Sales Shed is visible, to the left.

On that cloudy morning, even the view from Great Dixter’s parking lot was inspiring. Yes, this is my first Sheep-Picture of the Day. Steve Parry advised me that the small brick building in the field is called “A Lookerer’s Hut,” another name for a Shepherd’s Hut. Shepherds were called “Lookerers.”

I don’t think of Christopher Lloyd as a garden designer. Instead, I regard him as the weaver of enormous, outdoor tapestries. Plants of all descriptions were the warp and weft of his gardening life. With a craftsman’s eye, he combined colors and textures. And with a stage-designer’s cunning, he juxtaposed plants of drastically-differing sizes, and then positioned them contrarily… anything to add some drama and sizzle to each part of his garden. Formal rose bushes, all together in rows? Bah! Why not some towering Japanese banana plants instead…with a few dahlias thrown in, just to keep the traditionalists pacified. Lloyd was not an artist who sought to create gardens that paid homage to the spirit of the landscape. Rather, his inward-looking gardens are almost brain-maps; illustrations of the feverish workings of the mind of a born horticulturalist. So what if the beautiful borders that he devised would need obsessive and skilled tending? Lloyd unapologetically made gardens that required massive quantities of labor; after all, he had the time and wherewithal. Now that Christopher Lloyd and his two pooches are gone, his gardens are still just as needy, but apprentice gardeners from around the world throng to Great Dixter, where head gardener Fergus Garrett puts them to good use as he teaches them how to throw planting-inhibitions, and plants’ seeds, into the wind.

Destination #2: The Mermaid Inn Mermaid Street Rye East Sussex TN31 7EY Phone: 01797-223065 Website: www.mermaidinn.com

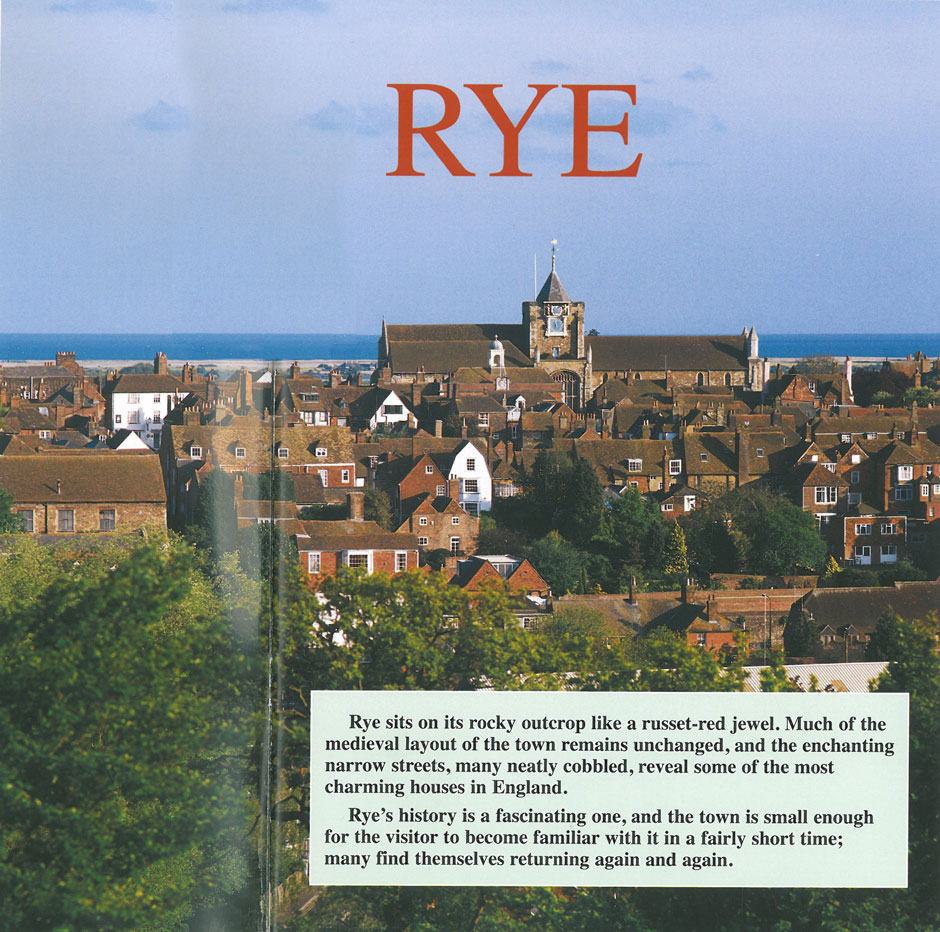

Since lunchtime approached, Amanda had scheduled our next stop to be at the Mermaid Inn, in the ancient town of Rye.

The Mermaid Inn is on Mermaid Street, in the

hilltown of Rye. In the early 1700’s the Mermaid Inn was used as a meeting place by the notorious smugglers known as the Hawkhurst Gang, who were seen there, “carousing and smoking their pipes, with loaded pistols on the table before them…and no magistrate daring to interfere.” Happily, when Amanda and I eventually enjoyed our lunch in the bar, there were no smugglers to be seen. Image courtesy of RYE, by Ann Lockhart.

Steve dropped us off at the foot of Mermaid Street, and Amanda and I began our hike up the rough, cobbled roadway. Rye is a strictly flat-shoes-with-good-traction place! Don’t even think about approaching it without proper footwear.

We began a fast trot toward the upper reaches of the town. Halfway up Mermaid Street, we took a right turn, which led us to Watch Bell Street.

This is the Old Bell, on Watch Bell Street. From 1377 onward, a bell has always been hung here, to warn Rye’s citizens that invaders are approaching. The current bell has, happily, never been rung in times of trouble. Engraved upon it: “Thomas Lester Made Me, 1740.” Lester was the Master Founder of the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, in London. In 1752, this company also cast America’s original Liberty Bell. They also made Big Ben, for the Palace of Westminster.

And now, a digression: This is the Whitechapel Bell Foundry, in London. In continuous operation since 1570, the Foundry is Britain’s oldest business. 32/34 Whitechapel Road, London, E1 1DY.

www.whitechapelbellfoundry.co.uk.

Photo courtesy of Anne Guy.

We’re still in London, at the Whitechapel Bell Foundry. Here are some of their exquisite creations. Photo courtesy of Anne Guy.

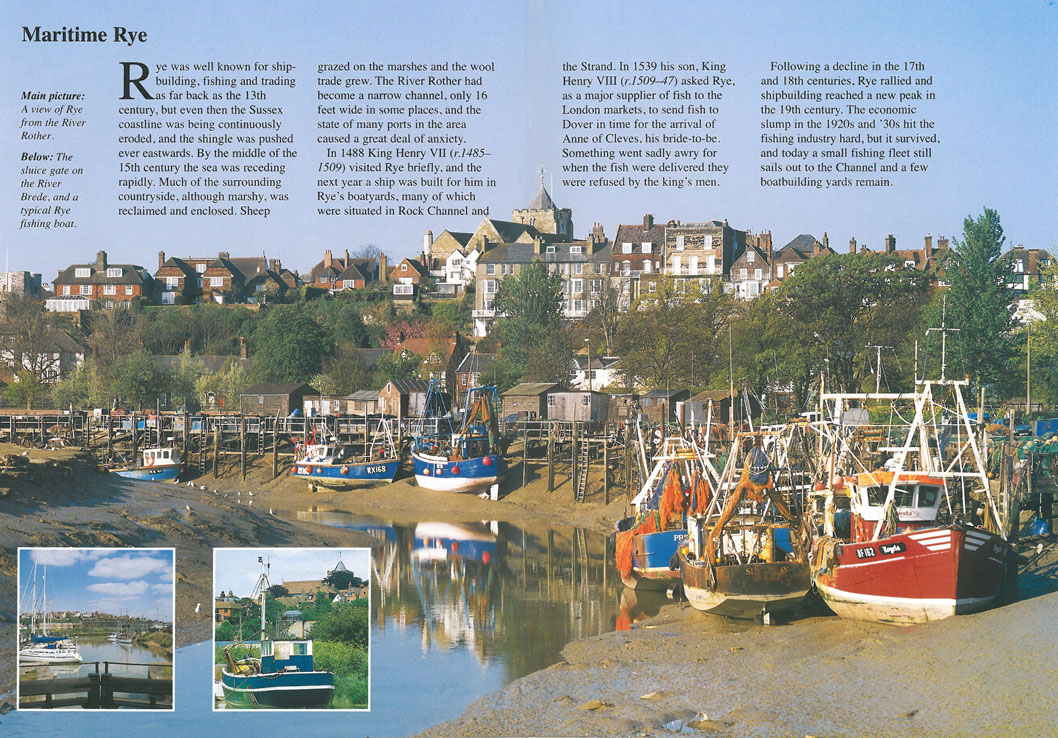

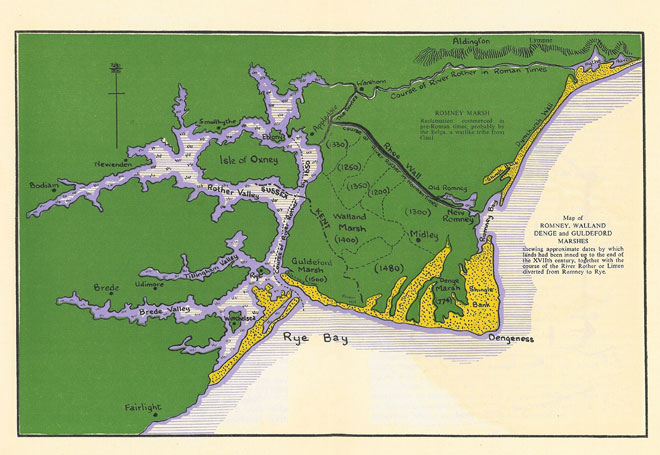

As we lingered by the Old Bell, we looked southward toward the English Channel, out over the marshy lowlands that surround Rye. Amanda asked me to imagine that those green expanses had once been the shallows of Rye Bay.

A late 17th century painting of Rye, which shows the town perched on a rocky outcrop, and surrounded by marshy fields where vast herds of sheep grazed. Image courtesy of the Rye Museum Association.

By the middle of the 15th century, constant erosion of East Sussex’s coastline had drastically changed the contours of the land, and the channel of the River Rother, which flowed directly to Rye, had greatly narrowed. Rye, which from 1066 onward, had become a major port and trading center, was now inland.

Ann Lockhart’s guide to the town, “RYE,” nicely summarizes the history of Rye and the Cinque Ports. “The Confederation of the Cinque Ports has its roots in the 11th century and originally consisted of the five ports of Dover, Hastings, Hythe, Romney and Sandwich. Rye and Winchelsea has been included as ‘limbs’ of Hastings by 1189, and were made full members in 1336. The Confederation was formed as a means of mutual protection and for the benefit of trade. Approved by Royal Charter, certain rights and privileges were conferred on the ports in exchange for services to be rendered to the Crown. These included supplying ships and men for a set number of days per year, and in times of trouble. “

BUT….despite official Charters, and trade agreements, by the early 14th century, as soon as King Edward I had introduced a tax on the export of wool, the liveliest portions of Rye’s economy began to depend upon smuggling. So vigorous was the subterranean economy that nearly everyone living in Rye somehow cooperated with the smugglers, and this tax-avoidance went on for hundreds of years, until the 19th century, when the abolition of many of the duties, along with reforms instituted by the Customs Service, finally killed smuggling’s profitability.

Further along Watch Bell Street, we came upon this beautiful, stone building, which is the oldest structure in Rye. Originally built as a monastery, in 1307 it was denounced by the Pope for housing monks and nuns on the same premises (egad), and so became a private residence. It was one of only a few of Rye’s buildings that survived the French razing of the town, in 1377.

Across Watch Bell Street from the old monastery, and behind this stone wall, is the Churchyard and burying ground of St.Mary the Virgin.

The Churchyard is on the highest part of Rye’s Conduit Hill. Image courtesy of RYE. by Ann Lockhart.

Directly opposite the Churchyard on Watch Bell Street are these ancient buildings, which date from the 15th century.

At the far end of Watch Bell Street, we found The Ypres Tower, which dates from 1250. Henry III built this as a defense against invaders. Clearly, it didn’t work…certainly not when the French breezed into town, in 1377. Over the centuries, this has been used as a prison, a courthouse, a monastery, and a private residence.

On the far side of The Ypres Tower, we looked out over the River Rother. The view from this point has changed considerably over the years. During the threat of the Spanish Armada in 1588, the high tide would have filled a large estuary, with wide open sea beyond. After the French sacked the town in 1377, sea-facing cannons were mounted on this spot.

If we’d climbed down to the bottom of Conduit Hill, this would have been our view of Rye, from the narrow channel of the Rother River. The steeple of the Church of St.Mary the Virgin is at the center of the town. Image courtesy of RYE, by Ann Lockhart.

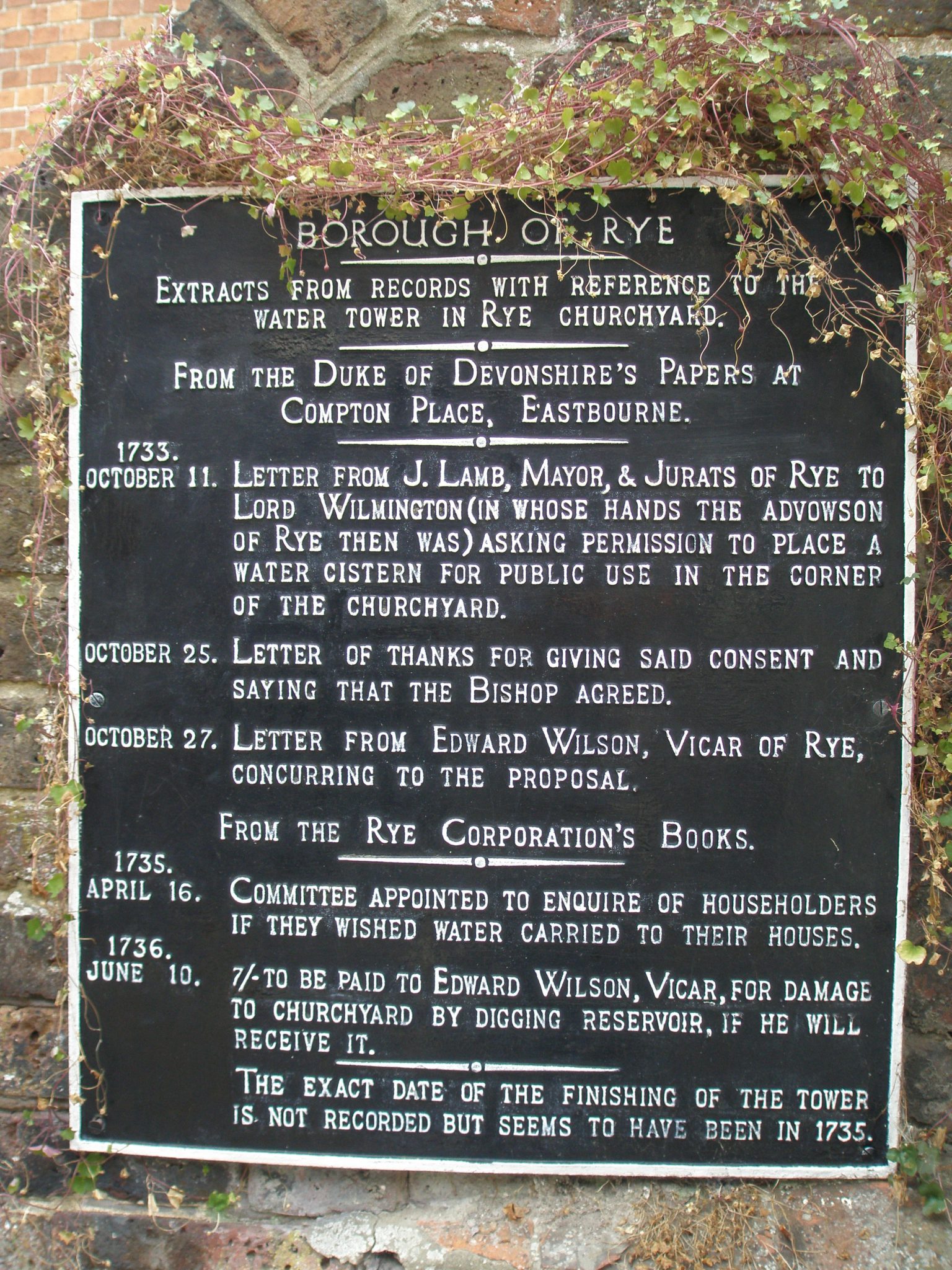

Adjacent to the Church of St.Mary the Virgin is the Water House (or Cistern), which was constructed in 1735.

Had the day been sunny, a Church-Tower-climb would have been in order. Here’s the view over Rye, from the Church tower. Image courtesy of RYE, by Ann Lockhart.

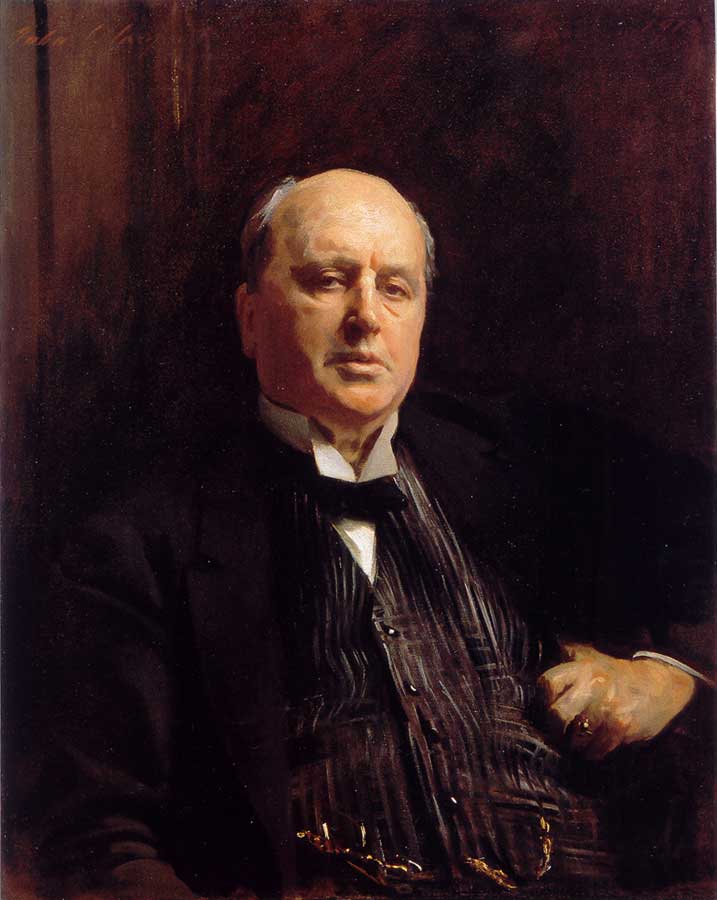

Near to the Church, where Market Street meets West Street, is Lamb House. Henry James lived here, from 1898, until his death, in 1916.

I’d had NO idea that Henry James—who, when he’s in good form, is one of my favorite authors—had spent the final and most artistically productive years of his life in Rye. Since Lamb House was closed on that Wednesday, I’ve already made plans with Amanda for us to actually get inside it, during my next trip to England, which will be very soon…this coming June.

I peered through Lamb House’s parlor window, and got a glimpse of these French doors, which lead to the private garden (yes…I’ll photograph that, when I’m back in Rye).

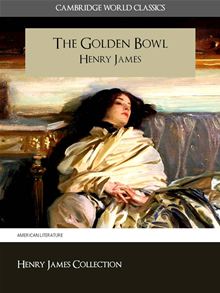

Yet another treasure, managed by England’s National Trust. While at Lamb House, Henry James wrote his two greatest, late-career novels: THE WINGS OF THE DOVE (published in 1902), and THE GOLDEN BOWL (published in 1904).

THE WINGS OF THE DOVE takes place in London and in Venice…two of my favorite cities. Read it: under its polite surface, a gritty novel lurks.

THE GOLDEN BOWL is a long, challenging slog…but worth the effort. Attack its 568 pages during a sleepy August…that’s the month during which I’ve most enjoyed this story of betrayal, love, and sacrifice.

We’re at the top of Mermaid Street, about to head downhill to the Mermaid Inn, which is the ivy-covered building on the right hand side of the Street. Starvation had set in…’twas time for LUNCH.

The Mermaid Inn. Some of the timbers of the Inn were taken from ships that had been disassembled. For the occultly-inclined (which I’m NOT), the Mermaid Inn is reputed to be one of the most-haunted buildings in England. Of the Inn’s 31 bedrooms, 6 are said to be plagued by ghostly visitors.

The Mermaid Inn, which was rebuilt in 1420, stands on cellars that were constructed in 1156. During medieval times, the Inn brewed its own ale, and charged a penny a night for lodging.

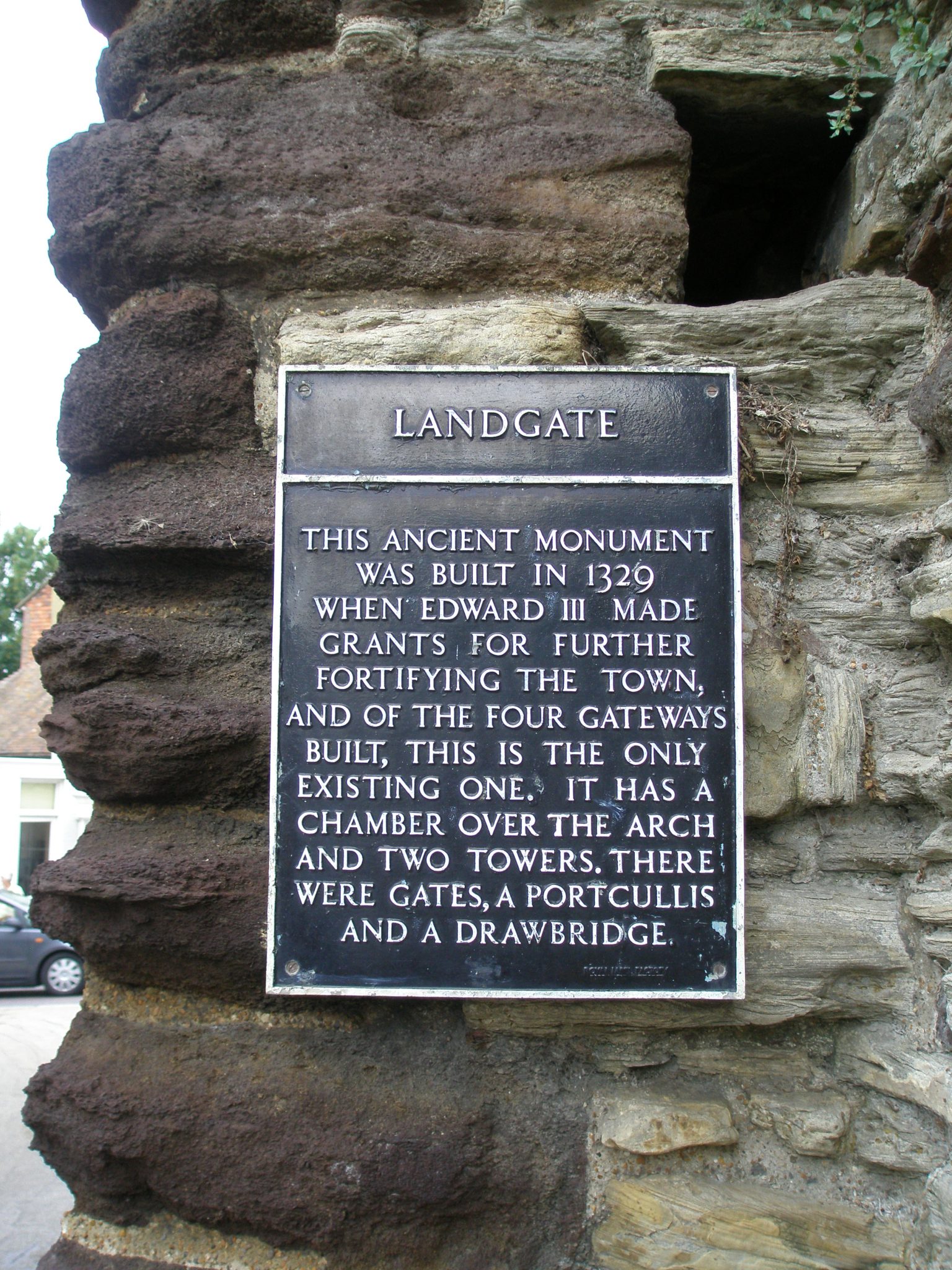

After our Mermaid Inn lunch—-which was very tasty—we headed down Rye’s High Street, toward Hilder’s Cliff, and the Landgate.

At the northeast corner of Rye is the Landgate, one of four gateways that were built in 1329, when a great wall was erected around the perimeter of the town. The Landgate is the only gate that’s survived. Originally, its two towers had pointed roofs, and a pitched roof was over the arch.

Our little Rye-Tour ended, we passed through the Landgate, and found Steve waiting patiently for us!

Just as the Rye Town Guide promises, a return trip is inevitable. I’ll report about my upcoming visit to Lamb House in a future Armchair Traveler’s Diary. Image courtesy of RYE. by Ann Lockhart.

Before our next garden stop — Derek Jarman’s Prospect Cottage on the shingle beach at Dungeness — Amanda and Steve agreed that I should see a bit of the vast, 100-square-mile expanse of fabled Romney Marsh, which was where the liveliest smuggling activities on England’s southern coast occurred. The outlaws are long gone: the Marsh is now populated largely by sheep.

The view from Rye—there’s our Ypres Tower again—across the River Rother, and out over the great expanses of Romney Marsh.

Steve began to thread his way along the narrow roads that wind through the Marsh. Hundreds of small, drainage ditches — called “sewers” —snake across the lowlands–and roads usually follow those ditches….however circuitous their paths. The heavy overcast made it impossible for me to use the sun’s position to judge our direction, so I forgot about backseat driving, and simply gawked at the eerie landscapes, while I imagined smugglers, skulking about under similarly leaden skies, as they moved their cargoes of wool. I rolled down my window, and heard cacophonies of bird-calls echoing. Clearly, if you’re into either sheep-or-bird-watching, Romney Marsh is the place to be. I can imagine that, at a future and quieter time of my traveling-life, I’ll stay for a few nights in Rye, so that I can spend my days, rubber-booted and sloshing about in the Marsh, with camera and binoculars in hand.

Per the Royal Society for Protection of Birds ( www.rspb.org.uk ) , “The Romney Marshes are a very important area for farmland birds, owing to the presence of key species: grey partridges, corn buntings, turtle doves, tree sparrows, yellow wagtails and lapwings. In addition, there are populations of other red-listed [endangered] species, including skylarks, yellowhammers and linnets.”

This church, St. Thomas Becket, is in the “lost village” of Fairfield, one of nearly a dozen villages, with fabulous names like “Snave,” “Shorne,” “Buttdarts,” and “Orgarswick,” which have disappeared from the Marsh, over the past 600 years.

St.Thomas Becket Church, in the lost village of Fairfield, on Romney Marsh. This medieval church was often surrounded by flooded fields, and thus only reachable by boat. The building was reconstructed in 1912.

Per Wikipedia’a handy entry on Romney Marsh Sheep: “The economy and landscape of Romney Marsh was dominated by sheep. Improved methods of pasture management and husbandry meant the marsh could sustain a stock density greater than anywhere else in the world. The Romney Marsh sheep became one of the most successful and important breeds of sheep. Their main characteristic is an ability to feed in wet situations; they are considered to be more resistant to foot rot and internal parasites than any other breed.” Here are some other-day views of the Marsh, taken by photographers who’ve posted their pictures to the web:

Destination #3: Church of St. Augustine. On Straight Lane, just off the A259 Road Broookland, Kent Postcode district TN29

Our next stop in the Marsh was the village of Brookland—population about 400— where the main attraction is the Church of St. Augustine. Again, Wikipedia has done all of my thinking for me (which I appreciate…sometimes I need to rest my brain.): “The parish of Church of St.Augustine has the unusual, if not unique, feature of an entirely wooden spire being separate from the body of the Church. Popular myth is that the steeple looked down at a wedding service to see such a beautiful bride marrying such an unpleasant groom that it jumped off the church in shock. A more popular story is that one day a virgin presented herself to be married and the church spire fell off at the unusual occurrence. In fact, it is separate as the weight cannot be supported by the marshy ground.” Thank-YOU Wikipedia…which reminds me: Each year when Wikipedia asks me to contribute some money to support their site, I do so gladly….and so should you!

Brookland’s Church of St.Augustine, with its separate steeple. The 3-stage, “Candle-Snuffer” configuration of the steeple is the result of several additions to the original, 13th century bell-cage.

It’s exactly 2:25PM, and we’re about to enter the Church of St.Augustine through the wooden porch that was added in the 14th century.

The main portion of the Church of St.Augustine was built in 1250. The box pews were added in 1738. This is still a functioning Anglican parish.

The Font is decorated with 12 panels showing the signs of the Zodiac, which are accompanied by images of the typical labors of each month.

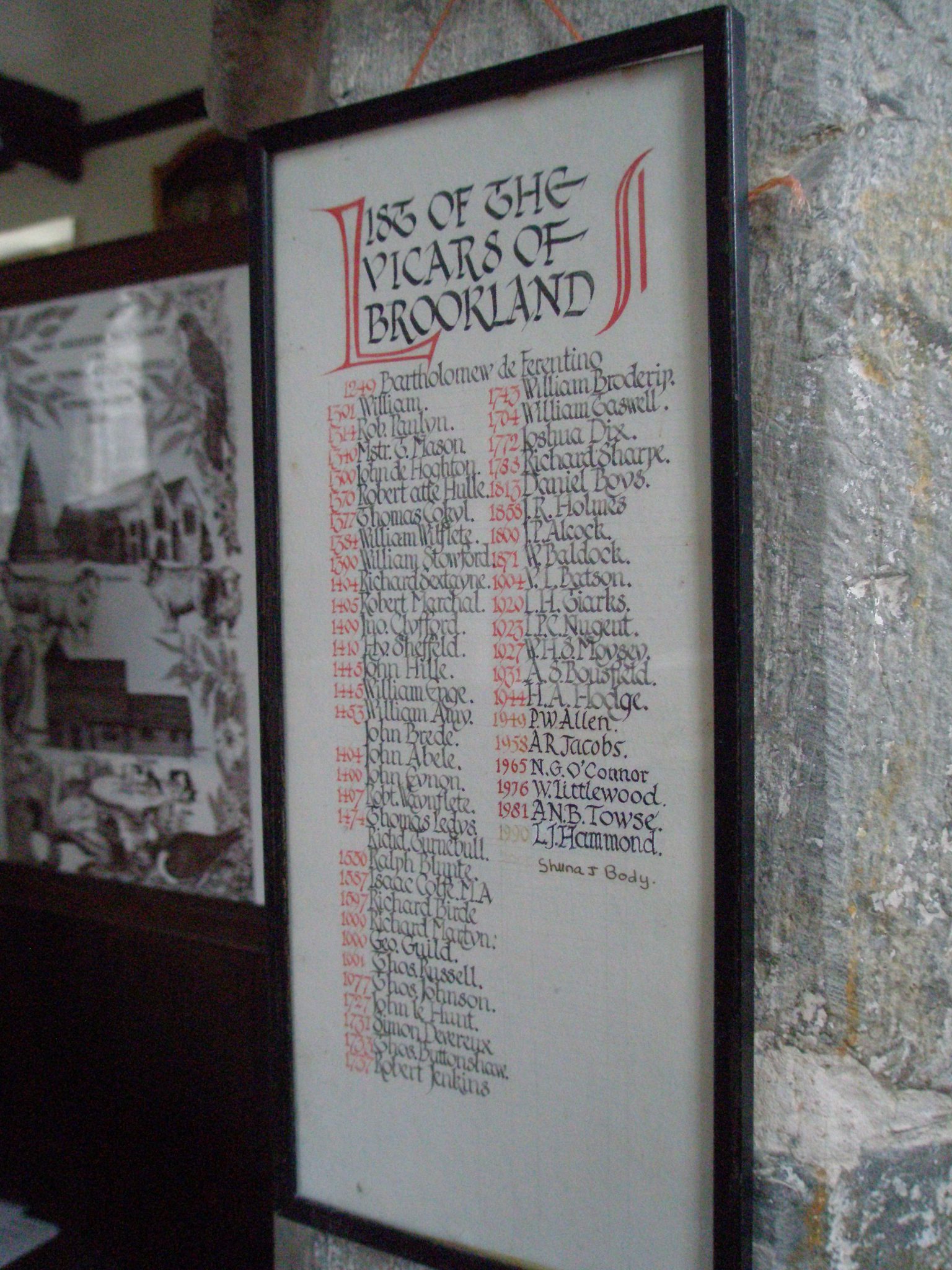

The Church of England has a LONG MEMORY. Here’s a list of the Vicars of Brookland, from 1249 to the present.

And what would England be without her Tea Towels! This is displayed in the Church of St.Augustine, and I’m sorry none were for sale.

Destination #4: Derek Jarman’s garden at Prospect Cottage On Dungeness Road. Dungeness, Kent Postcode district TN29

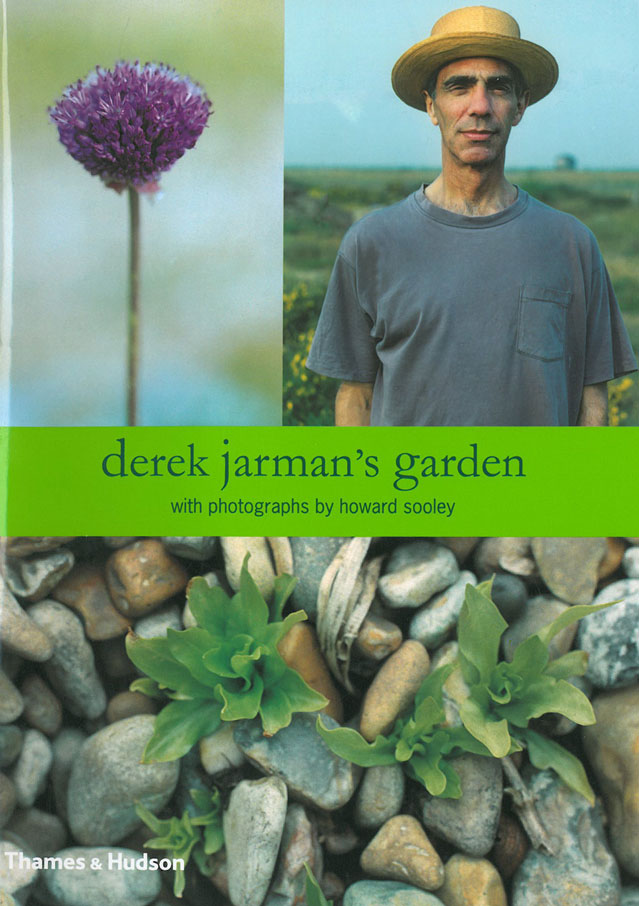

Derek Jarman was an English film director, stage designer, painter, gardener and author (born 1942, died 1994). This is the front cover of the last book that Jarman wrote, before his untimely demise from AIDS. Image courtesy of Estate of Derek Jarman.

How now, should I describe this next, and most important stop, of our day? When the maker of a garden is long gone, and where no organization has thereafter stepped in to restore and maintain those gardens, a student-of-gardening is posed with a challenge to her imagination. Almost-lost gardens such as Derek Jarman’s are places which, in many ways, cannot become REAL until historical knowledge is gained, and then merged with present-day sensation…..sensation which can only be acquired by BEING on the site of the garden in question.

The garden that Derek Jarman made is, in many respects, NOT what we expect an English garden to be; certainly the grounds at Prospect Cottage do not look like they belong in Kent, aka “The Garden of England.”

And the garden that exists today at Dungeness is NOT truly Jarman’s garden, because Derek has been dead and gone for 20 years.

Further, the current owners of Prospect Cottage are private folks, who have NOT opened the grounds around their home to the garden-loving Public.

All a visitor to the shingle beach at Dungeness can do now is to linger conspicuously ( because IN-conspicuousness is impossible: there’s not a tree or hedge growing anywhere on the headland of Dungeness. ) on the shoulder of Dungeness Road, as she tries to gawk politely at the garden, which though faded, is still recognizably Jarman’s creation. To get a closer look, a bold soul might walk around what seem to be the edges of the property, but since Jarman’s former garden is unconstrained by fencing, it’s hard to know at what point one has begun to trespass.

So…considering all these NOTS, there’s explaining to do:

Unless we travel to Dungeness, and stand on the rocky beach, and feel the sharp particles of grit that are borne against our faces by the constant wind; unless we walk along the village’s single road, and realize that, apart from the crunching of our feet on the gravel, the only sounds we hear come from the breeze and surf, and from the seabirds who soar overhead; unless we stand and gaze at the rusted fishermen’s shacks which are scattered along the beach, and then squint our eyes to focus upon the hulking gray mass of the distant Nuclear Power Station which serves as the backdrop for every other built thing in Dungeness…until we’ve done these things, we cannot begin to appreciate why Dungeness worked so powerfully upon Derek Jarman’s imagination.

There’s not much of a There THERE at Dungeness. The first sight that greets the traveler is the Pilot Inn, an unprepossessing, fork-in-the-road-restaurant that dishes up what Jarman considered to be “simply the finest fish and chips in all England.”

Dungeness has an otherworldly feel. With one of the largest expanses of shingle in Europe, it is classified as Britain’s only desert. The British military has long used the beach and marshes there for training exercises; to this day, DANGER AREAS are marked. And despite the safety risks posed by the Dungeness Nuclear Power Station (waste hot water from the Station is pumped into the sea), multitudes of birds and insects flourish there, along with more than 600 types of plants. In fact, a fistful of conservation designations have been conferred upon what at first glance seems a Godforsaken place: it’s a National Nature Reserve, a Special Protection Area, a Special Area of Conservation, and the Site of Special Scientific Interest (or NNR; SPA; SAC; and SSSI, for those who prefer acronyms).

Alexander Pope (born 1688, died 1744) popularized the ancient Roman notion of Genius Loci…the idea that a garden should always exist in harmony with its setting. He admonished:

“Consult the genius of the place in all; That tells the waters to rise, or fall; Or helps th’ ambitious hill the heav’ns to scale, Or scoops in circling theatres the vale; Calls in the country, catches opening glades. Joins willing woods, and varies shade from shades, Now breaks, or now directs, th’ intending lines; Paints as you plant, and, as you work, designs.”

My dear friend, the British garden designer Anne Guy, has told me this about Prospect Cottage: “I have to say that Jarman’s garden is my most favourite garden ever. Its simplicity, and its homage to genius loci results in a true work of art and understanding that’s quite unsurpassed by wealth and ‘taste’ of the classic gardens. Also its remoteness and strange proximity to the Dungeness power station…I could go on for hours!”

Consider this. You’re not-yet-old. You’ve just been given a death sentence. Do you put on your bathrobe and retreat into a dark room? Or do you go outside, and with your remaining energies begin to consider all the things under the sun that you might still gracefully accomplish?

This was Jarman. In 1986, when he was 45, Derek was diagnosed as HIV positive; which, in those early days of the AIDS crisis, meant that he would die soon, and painfully. Instead of hiding his condition, Jarman spoke openly about it. Knowing that his failing health could no longer sustain his frenetic, London-based life as a painter, and director of stage-plays, and of films and music-videos, Jarman traveled to Dungeness, which is literally one of the quietest places in England. He bought a fisherman’s cottage—a house with jolly, varnished black walls and bright yellow window frames that he’d long admired—and prepared to leave life with as much dignity as he could summon: perhaps he’d paint a bit, and do some writing. Those low-keyed activities would have to suffice…

From childhood, Jarman had been a gardener, but making a garden at Prospect Cottage had never been part of his Last-Act-Script. However, almost by accident, a garden began to form around his cottage. Jarman’s daily walks along the shingle beach yielded treasures that appealed to his artist’s eye. Piles of polished stone, shards of tide-scoured flint, bundles of bleached driftwood, and twisted lengths of rebar began to accumulate outside his front door. Almost without thought Jarman began to arrange his stones in patterns on the ground, and to stake newly-planted beach-roses with the driftwood, and to barricade tender plants behind the curlicues of rusted metal. The detritus of Dungeness had began to act upon Jarman’s Artist-Self.

In his creative endeavors, Derek Jarman had never shied away from controversy; his films dwelled upon themes of sexuality and violence. When I set myself the task of writing about any garden made by an author, or filmmaker, I do my homework. I read the author’s writings, and watch the director’s films.

As I prepared for this Derek Jarman Chapter of my Travel Diary, I sought out Jarman’s most famous films (JUBILEE is supposed to be the UK’s first punk movie, but watching Adam Ant “act” was more than I could endure) and music-videos (see if you can tolerate watching ANYTHING with the Pet Shop Boys….) . I confess that, when it comes to drama, I prefer less histrionic acting than that favored by Jarman, so I stopped watching Jarman’s filmed work. I turned instead to Jarman’s little book about his Garden, and in those elegantly written pages, which are supplemented by Howard Sooley’s beautiful photos, I became acquainted with the clear-sighted artist and thoughtful man who Derek Jarman surely must have been.

There’s no need for me to paraphrase Jarman’s history of the creation of his garden. When you’re done with my article, buy his book, and you’ll gain a gardening-friend (DEREK JARMAN’S GARDEN. Published by Thames & Hudson. ISBN# 978-0-500-01656-5 ). Because the gardens that remain at Prospect Cottage are mere echoes of those which Jarman made, one could argue that, these days, a trip to Dungeness is pointless. But Jarman’s book, though lovely, does not begin to explain how the barren expanses of Dungeness make one FEEL. On the shingle beach, life seems stripped to its essentials. The very absence of visual and aural clutter cleanses the soul, and clears the deck for fresh ways of thinking.

GardenVisit.com, which can always be depended upon for a good summary, describes Jarman’s garden as: “postmodern, and highly context-sensitive; a complete rejection of modernist design theory. Jarman disliked the sterility of modernism; he despised its lack of interest in poetry, allusion and stories; he deplored the techno-cruelty exemplified in Dr. D.G.Hessayon’s ‘How to be an expert’ series of garden books. Jarman’s small circles of flint reminded him of standing stones and dolmens. He remarked that ‘Paradise haunts gardens, and some gardens are paradise. Mine is one of them. Others are like bad children, spoilt by their parents, over-watered and covered with noxious chemicals.’ ”

Now, please join me for a look at what Prospect Cottage looked like last August, as a bitter wind blew and rain spattered. After this brief, gray-day look at Jarman’s gardens, I’ll brighten things considerably with photos from Jarman’s own book, taken when his garden was in its prime. And, finally, I’ll share pictures taken on sunny days by Anne Guy, during her visits to Dungeness, in July of 2005 and 2006, when Jarman’s gardens were still nearly as gorgeous as they’d originally been.

Sign for the National Nature Reserve, directly across the road from Derek Jarman’s garden, on August 7, 2013.

Next, pictures of Jarman’s garden during his lifetime; all taken by Howard Sooley, for the book DEREK JARMAN’S GARDEN:

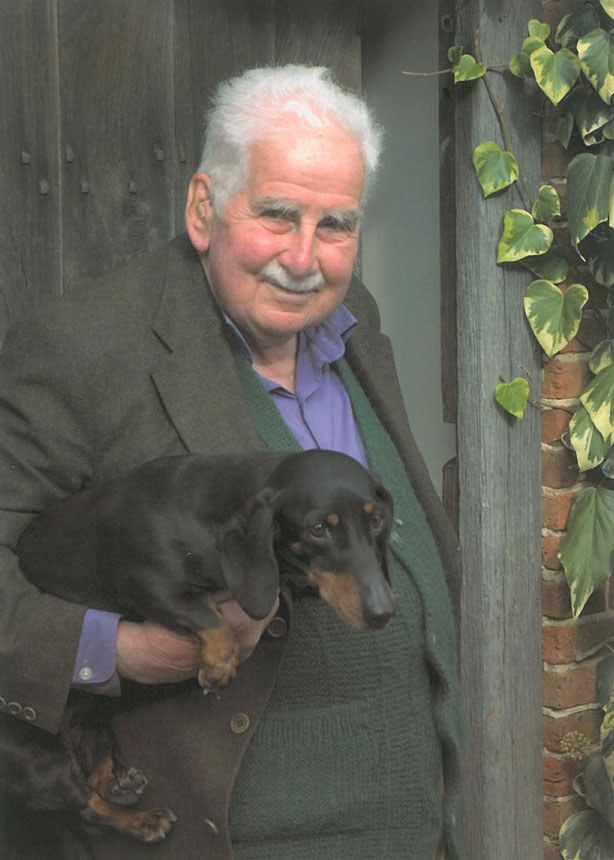

Derek in his back garden. When he arrived at Prospect Cottage he observed “it looked impossible: shingle with no soil supported a sparse vegetation.” Image courtesy of Estate of Derek Jarman.

Fennel, and poppy seed heads….two of the things in Jarman’s garden which the hoards of hungry rabbits didn’t consume. Image courtesy of Estate of Derek Jarman.

Jarman’s back garden, with the Dungeness Nuclear Power Station in the not-too-far-distance. Image courtesy of Estate of Derek Jarman.

Jarman watering in the seeds in his raised beds, where he grew herbs and vegetables. Image courtesy of Estate of Derek Jarman.

Rusted rebar and an old garden hoe are used as sculpture in Jarman’s garden. Eroded beach rocks become jewels, as they’re threaded onto the hoe tines. Cotton lavender plants frame the sculpture. Image courtesy of Estate of Derek Jarman.

Fragments of scrap metal and red poppies punctuate a sweep of beach rock. Image courtesy of Estate of Derek Jarman.

California poppies with sea kale, in a forest of driftwood. Image courtesy of Estate of Derek Jarman.

And finally, instead of thousands more of my words, Anne Guy’s eloquent photographs of Derek Jarman’s gardens, taken during her visits to Dungeness, in July of 2005, and 2006.

A telephoto view of the Dungeness Nuclear Power Station, taken from Derek Jarman’s garden. Photo by Anne Guy.

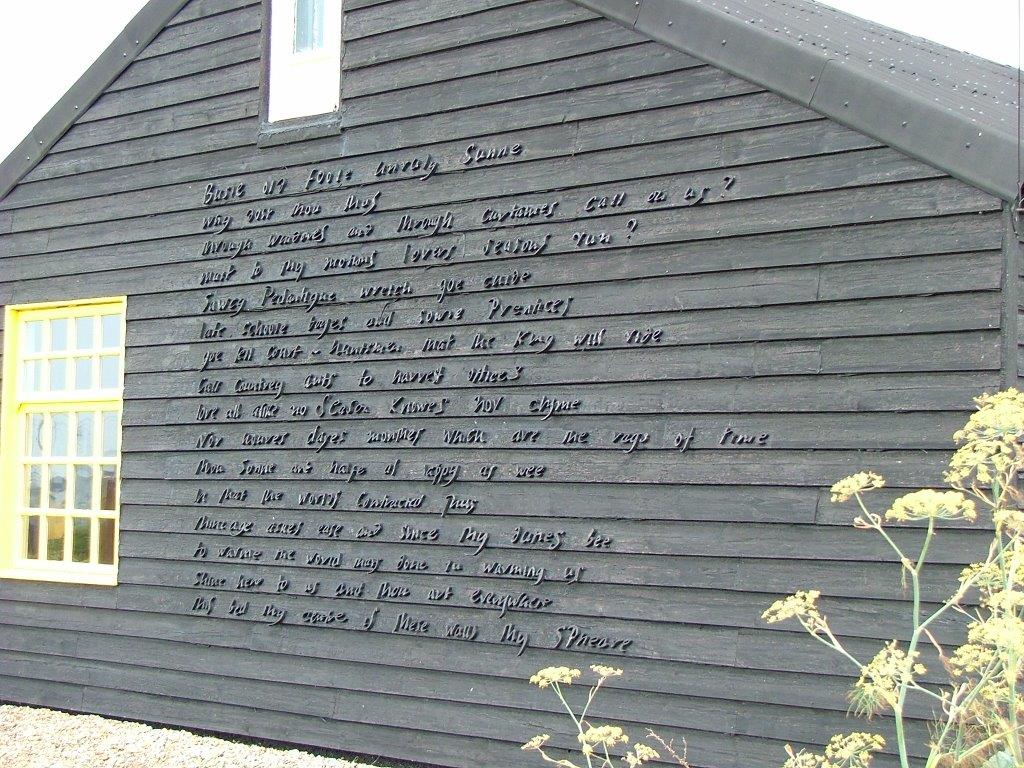

Derek Jarman chose his favorite portions of a John Donne poem, and had the words affixed to the wall of Prospect Cottage. Photo by Anne Guy.

The Sun Rising by John Donne “Busy old fool, unruly sun, Why dost thou thus, Through windows and through curtains, call on us? Must to thy motions lovers’ seasons run? Saucy pedantic wretch, go chide Late schoolboys and sour ‘prentices, Go tell court-huntsmen that the King will ride, Call country ants to harvest offices; Love, all alike, no season knows, nor clime, Nor hours, days, months, which are the rags of time. Thou, sun, art half as happy as we, In that the world’s contracted thus; Thine age asks ease, and since thy duties be To warm the world, that’s done in warming us. Shine here to us, and thou art everywhere; This bed thy centre is, these walls thy sphere.”

Prospect Cottage is an uncompromising place…and almost intimidating in its simplicity. Perhaps its power of place comes from the fact that Derek Jarman’s gardens were made as he savored Life and conversed with Death. And lately, as I’ve been thinking about my August visit to Dungeness, a memory about something which has nothing to do with gardens has become persistent. One morning in the spring of 2006, as my complex, ambitious and creative father Elwyn Belmont Quick accepted that the illness which he’d bravely fought was about to kill him, I brought just-baked bread to his hospital bed. I broke open the warm loaf, spread it with sweet butter, and fed it to him. He took a bite, and then smiled the happiest smile I’d ever seen him make. “Nan,” he said, “We have everything we need.” As I now appreciate the way in which Derek Jarman—yet another restlessly inventive person—used the simplest of materials, scavenged on the shingle beach, to make his own little paradise, I’m certain that, as he positioned driftwood and arranged beach rocks and broadcast wildflower seeds, he must also have thought, “Yes, I have everything I need.” Bread and Butter, or Sunshine and Stone? Whichever combination makes us happy, we should try to remember that the smallest blessings are our greatest treasures, in the end.

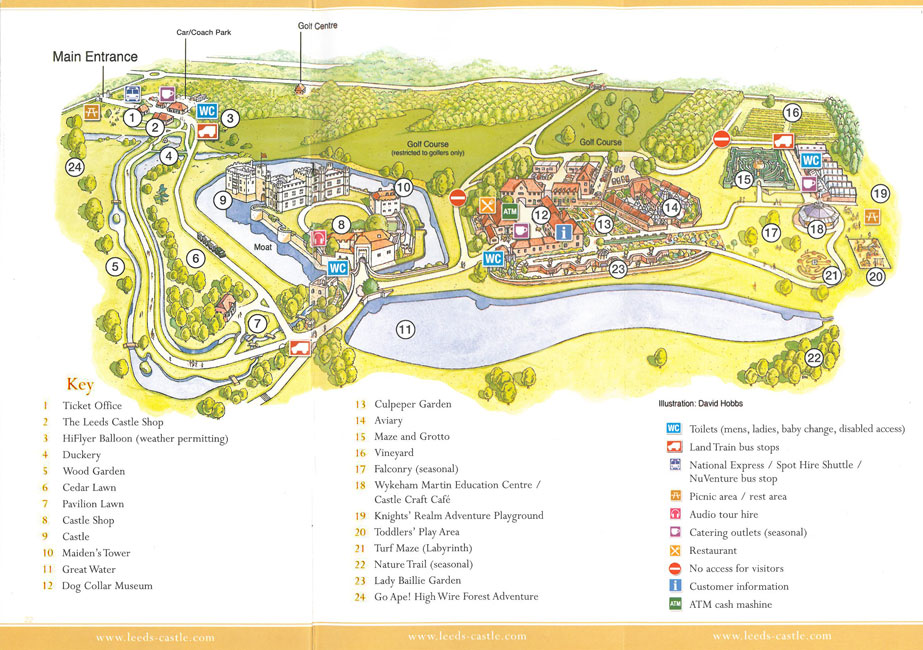

Destination #5: Leeds Castle

Ashford Road

Maidstone, Kent ME17 1PL

Open year-round.

Hours: Daily, 10:30AM– 4:30PM

Phone# 01622-765400

Website: www.leeds-castle.com

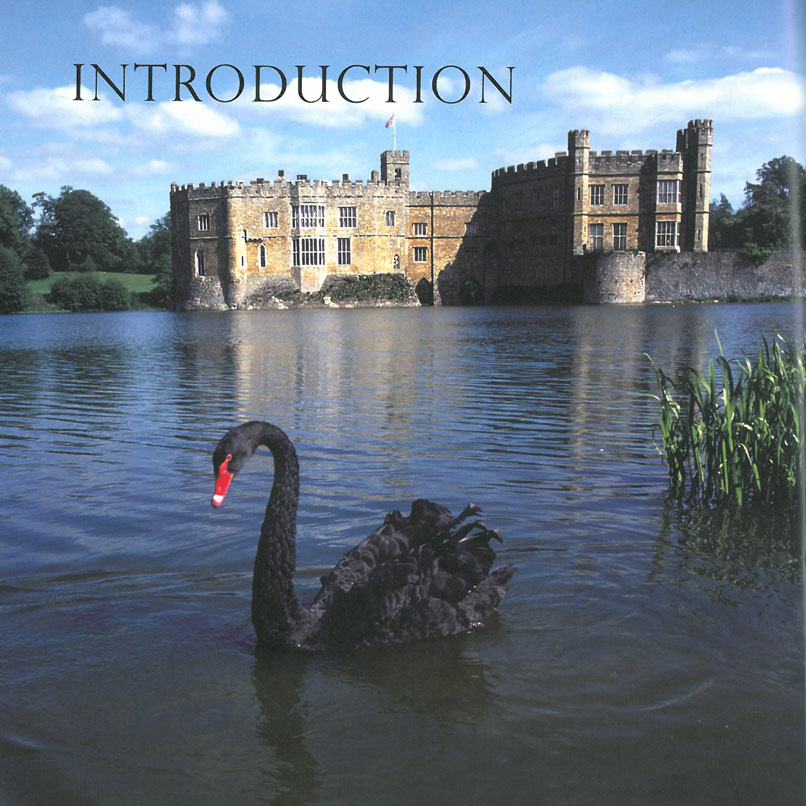

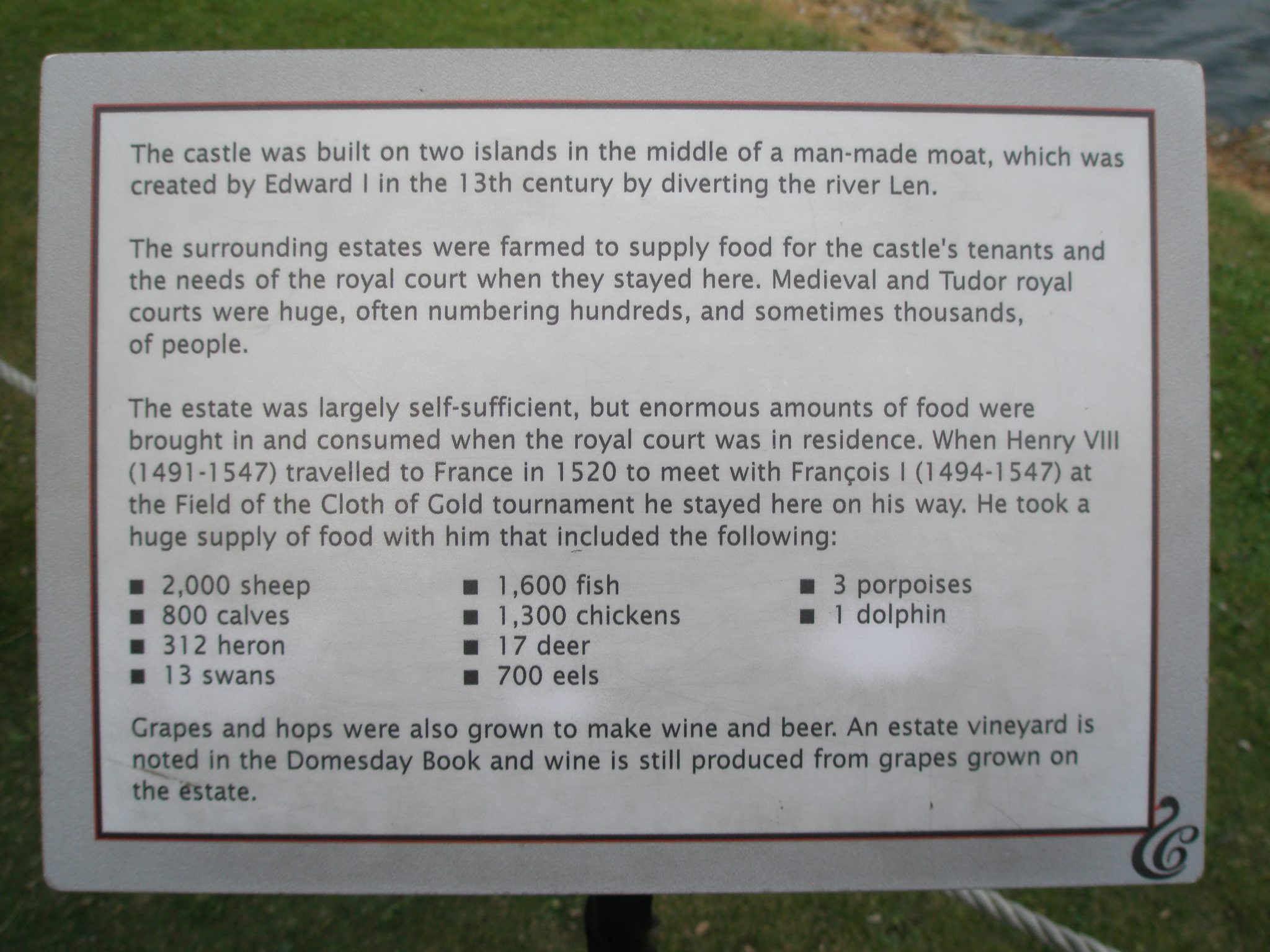

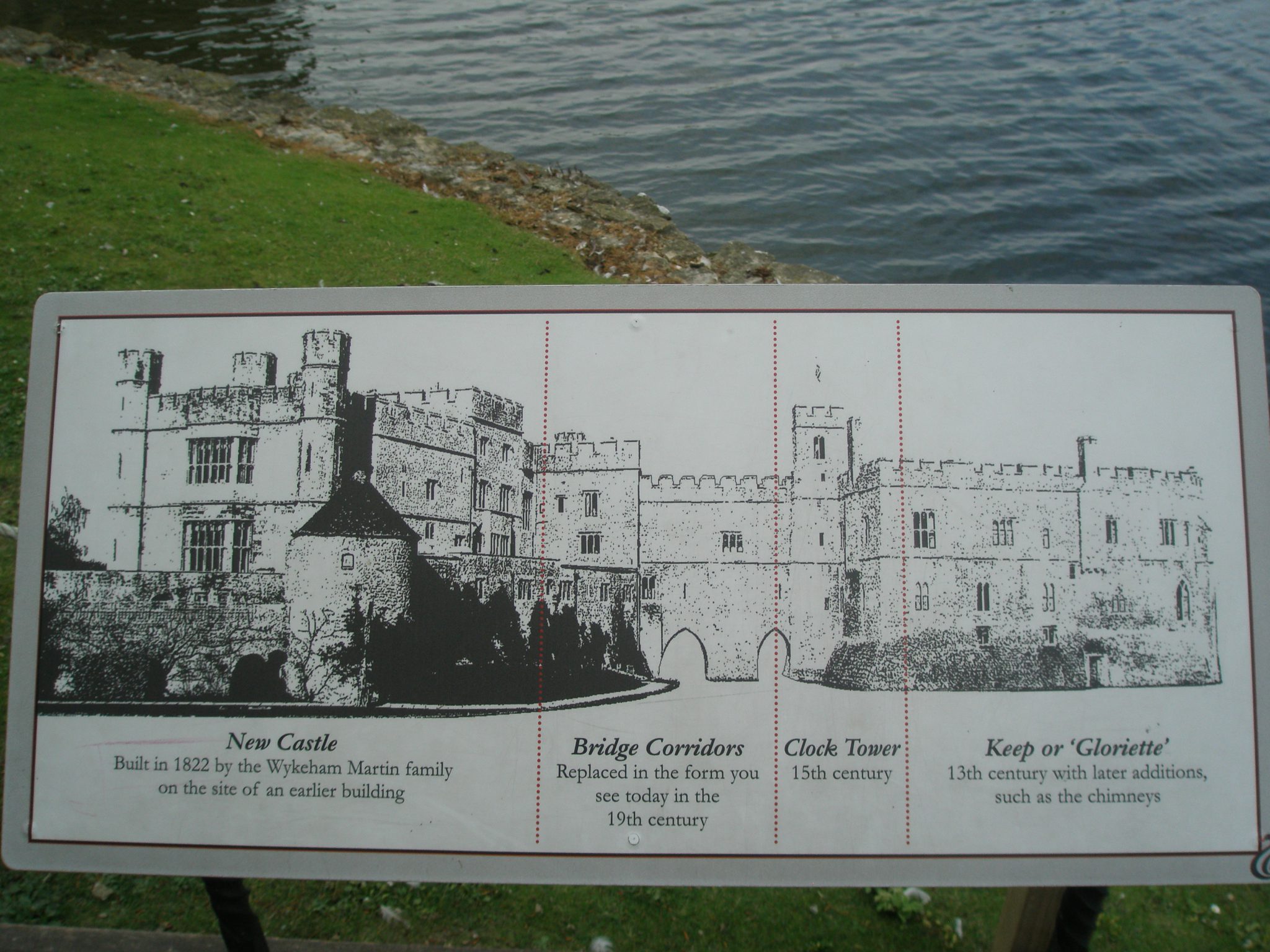

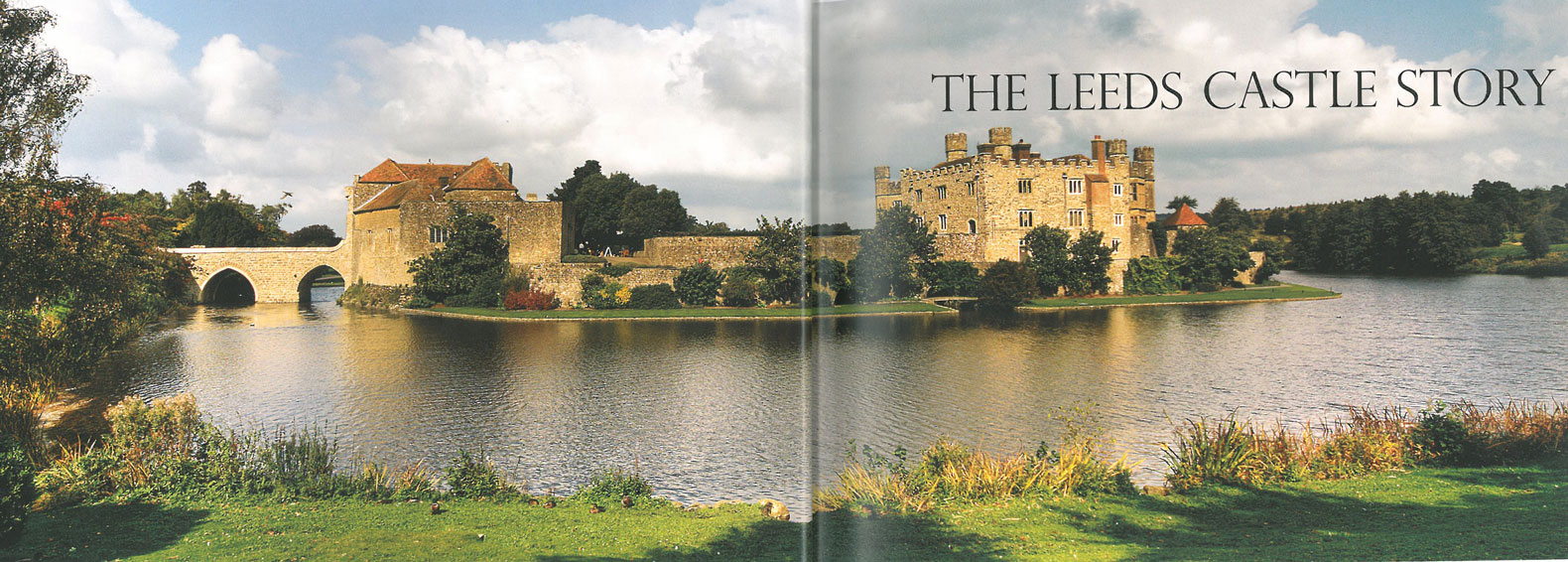

Since 1119, Leeds Castle has perched upon an island in the River Len. Over the past 900 years, the castle has been greatly expanded. It began as a Norman stronghold, and has since been the private property of six of England’s medieval queens; and a palace used by Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. After 1552, the castle passed into private ownership, and was owned successively by the Culpeper, Fairfax and Wykeham Martin families. In the early 20th century the Castle became the retreat of Olive, Lady Baillie, an Anglo -American heiress. Image courtesy of Leeds Castle.

After the extreme excitement of our Day (because visiting the gardens of people like Christopher Lloyd and Derek Jarman sets my brain abuzz), ‘twas time for me to stop pondering theories of garden design. Now I’d decompress with a visit to a nice, soothing castle, where I’d do nothing more taxing than mindlessly ogle a beautiful and ancient building! See how jaded a week of Kent-touring can make a traveler? That I could consider seeing Leeds Castle, which is one of the most-visited historic sites in England, to be a relaxing and relatively-normal occurrence shows how wonderfully spoiled Amanda’s tour-guiding had made me. (Which is why, Gentle Reader, during this coming June, I’ll once again be putting myself into the expert hands of Amanda and Steve…as we explore places in Kent that we didn’t get to last August.)

At 4PM, Steve delivered us to the Main Entrance, and then Amanda and I set off at a fast clip toward the Castle itself, which is a fair distance from the Entrance. Amanda and I are both tall ladies, and so, happily, our long strides matched. Join us for a photo-album tour, as we explore yet another of Kent’s moated-jewels.

We trotted past the area named “The Duckery,” which at first glance looked far like a “Goosery.” Lady Baillie loved birds, and asked her garden designer, Russell Page, to develop this pretty area of parkland into a welcoming environment for waterfowl.

The approach to Leeds Castle, with one of the Estate’s omni-present Black Swans. Lady Baillie was the first person to import black swans from their native Australia to the United Kingdom. Image courtesy of Leeds Castle.

We passed the remains of the Barbican, an outer fortification that was created in the 1280s. The Barbican served as an initial line of defense for the bridge crossing the moat to the gatehouse. In addition to protecting the Castle bridge, the Barbican contained locks which controlled the water levels of the moat. In dangerous times, the river could be flooded to prevent access to the Castle.

We approach the Gatehouse, part of the original 12th century stronghold, which was then enlarged by Edward I in 1280.

Amanda leads the way, over the stone bridge which leads to the Gatehouse. This bridge would originally have been a wooden drawbridge.

We passed through the arch of the Gatehouse onto the New Castle’s large, oval lawn. The New Castle, which replaced a succession of buildings on this site, was built in the 1820s.

But what I most wanted to see was the oldest part of Leeds Castle, the Gloriette. To get there, Amanda led me along a waterside path.

Another view of the Bridge Corridors. During Norman times, a wooden drawbridge was here. Later on, the massive, multi-storey bridge appeared. The Bridge Corridors that we use today were reconstructed in the 19th century. Image courtesy of Leeds Castle.

The Gloriette (the right-most building), which is built on its own little island, was constructed in the late 13th century for Eleanor of Castile, on the site of the original Norman keep. The Gloriette consists of a central courtyard, a great hall and other ceremonial rooms on the ground floor, and a series of apartments on the upper floor. Image courtesy of Leeds Castle.

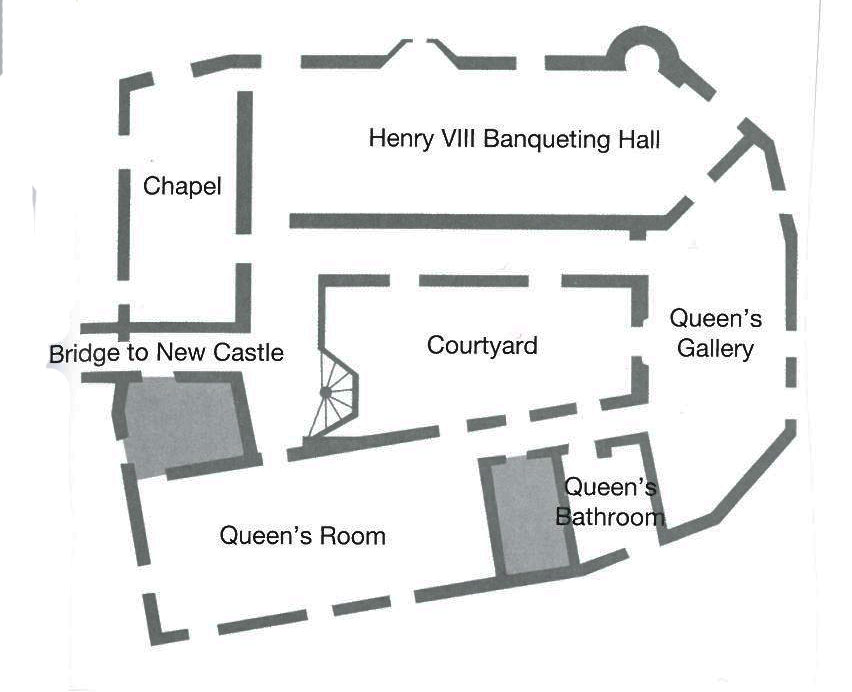

In the Queen’s Room, named for Henry V’s French wife Catherine de Valois, Queen Catherine’s coat of arms decorates the hearth.

The Queen’s Gallery is the most dramatically-situated room in the Gloriette, and has broad views in two directions, across the water. Image courtesy of Leeds Castle.

The Fountain Court, the Gloriette’s central courtyard, is an enchanting space. The courtyard dates from the 1280s. Cisterns were installed beneath it, to which water was supplied from springs in the Park.

Henry VIII’s Banqueting Hall. This room was renovated for the visit of Henry VIII and his first wife Catherine, in 1520. They were en route for Dover, to embark for Henry’s meeting with Francis I of France, which would be called “The Field of the Cloth of Gold.” On that little outing, Henry had an entourage of 3997 people, and his Queen dragged along 1175 additional helpers. Image courtesy of Leeds Castle.

Bay windows in the Banqueting Hall. Prior to Henry’s arrival, the narrow arrow-slits that had served as windows in the Hall were replaced with the generous expanses of glass that now overlook the moat.

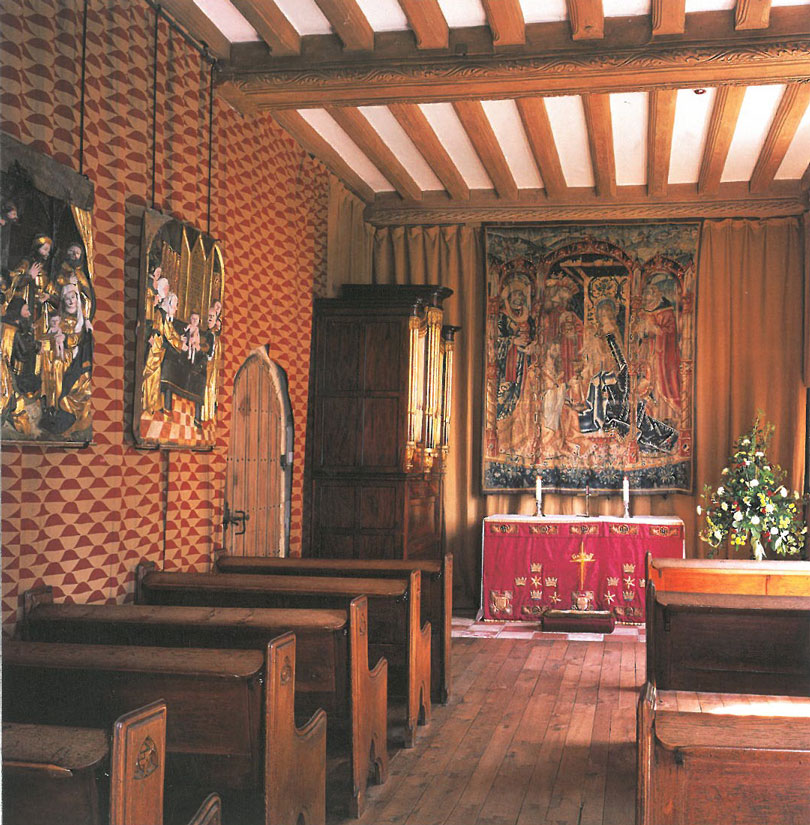

The Gloriette’s Chapel. A large, late 15th century tapestry depicting the Adoration of the Magi hangs above the altar. Image courtesy of Leeds Castle.

With little time to spare till closing time, Amanda and I skedaddled outside for a fast look at the gardens…which turned out to be nothing extraordinary, as compared to many of the other grand gardens we’d seen in Kent.

We entered the Culpeper Garden, which occupies the site that was long used for the Castle’s kitchen garden. The Culpeper Garden is the creation of designer Russell Page (born 1906, died 1985), and takes its name from the family which owned the Castle in the 17th century.

On a terrace below the Culpeper Garden, overlooking the Great Water, is the Mediterranean-style Lady Baillie Garden, which was designed in 1999 by Christopher Carter.

I love those red beaks, with white stripes…but the swans were mighty crabby when they discovered that I had no bread crumbs for them.

Closing time at Leeds approached. Amanda and I strolled along the moat, to the rear of the Castle.

To the Left: the rear elevation of the Maiden’s Tower (Nope….no actual tower there), which is a late-Tudor addition to the Castle. To the Right: the New Castle.

Continuing our walk around the moat, toward the back of the Island, we had this new view of the Gloriette (on the left), and the Bridge Corridors (center), and the New Castle (to the right).

As the afternoon light darkened, Amanda and I began our walk back to Steve, at the Main Entrance. (Note: The long, low wall with the rounded protrusions that extends from the New Castle all the way to the Gatehouse is called a Revetment Wall. This wall has stood since the 13th century.)

I hope this little picture-ramble at Leeds Castle has calmed you…but perhaps…instead… you’re exhausted, and in need of a nap? Rest up…there’s one more Kent-article on the way. We’ll begin with a visit to the estate at Goodnestone Park, near Canterbury, where Jane Austen often visited with relatives. We’ll explore The Salutation Secret Gardens on the seaside, at Sandwich, which Edwin Lutyens designed with his gardening-partner, Gertude Jekyll. We’ll hit the beach and Walmer Castle, which is one of a chain of coastal artillery forts built by Henry VIII. Your stomach will growl, as I tell you about the perfect, Dover sole I ate at a restaurant that sits at the base of England’s famed, white cliffs along the English Channel. We’ll wander through The Pines, a perfect little garden that’s perched at the top of those white cliffs. And then we’ll head inland, to finish off our marathon-tour in the refined and sunny gardens at Godinton, in Ashford.

It’s August 8, 2013, and we’re at the Edge of England! These are the white cliffs of Saint Margaret’s-at-Cliffe.

Copyright 2014. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express &

written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

3 Responses to Part Four. Rambling Through the Gardens & Estates of Kent, England.