Nan, in the mouth of the Ogre, at the garden of Sacro Bosco ( or Sacred Wood ). This one-of-a-kind garden, in Bomarzo, Italy, was begun in 1552. Photo taken on May 14, 2014.

For many years, I’d been contemplating making a trek to the hills of Northern Lazio, to see a duo of dramatically different gardens that had long piqued my curiosity. The Sacro Bosco at Bomarzo ( constructed from 1552 until 1588 ), and the Villa Lante at Bagnaia ( made from 1566 until about 1595 ) were created contemporaneously by two men, who were friends and neighbors. But Pier Francesco Orsini (aka the Duke of Orsino), and Cardinal Giovanni Francesco Gambara (aka The Bishop of Viterbo) were possessed of VERY different temperaments, which resulted in gardens with atmospheres that illustrate opposite extremes of Italian Mannerist-era style. To set the historical stage, I’ll refer to remarks made about Mannerism by scholar Luca Pietromarchi, who collaborated with Marella Agnelli on GARDENS OF THE ITALIAN VILLAS:

“In the first half of the 16th century, gardening became, especially in the great Roman gardens, far more than an arrangement of trees and flowers; it developed into an art form, an expression of order, symmetry and classical austerity. ‘Things that are built,’ wrote the 16th century sculptor Baccio Bandinelli, ‘must influence and predominate over things that are planted.’ “

“But in the second half of the century the secure belief in man’s absolute power over nature began to falter. In the literature and painting of the time the image of an orderly and disciplined natural world seems to have gradually crumpled under the impact of some uncontrollable force. Nature came to be represented as a secret and magical universe which could excite fear and surprise; a world that both charmed and frightened. These conflicting emotions influenced the gardens of the time, which exemplified aspects of the development of Mannerism, in which the strict rules of proportion and harmony that characterized Renaissance art and architecture were willfully distorted and a new emphasis was placed on emotional expressiveness.”

“In these Mannerist gardens art in no way yields to nature; while endeavoring to discipline the landscape and contain it…it also explores and reveals the mysteries of nature by imitating its marvels. Added was a spirit of scientific experiment, in which the architect became a hydraulic engineer.”

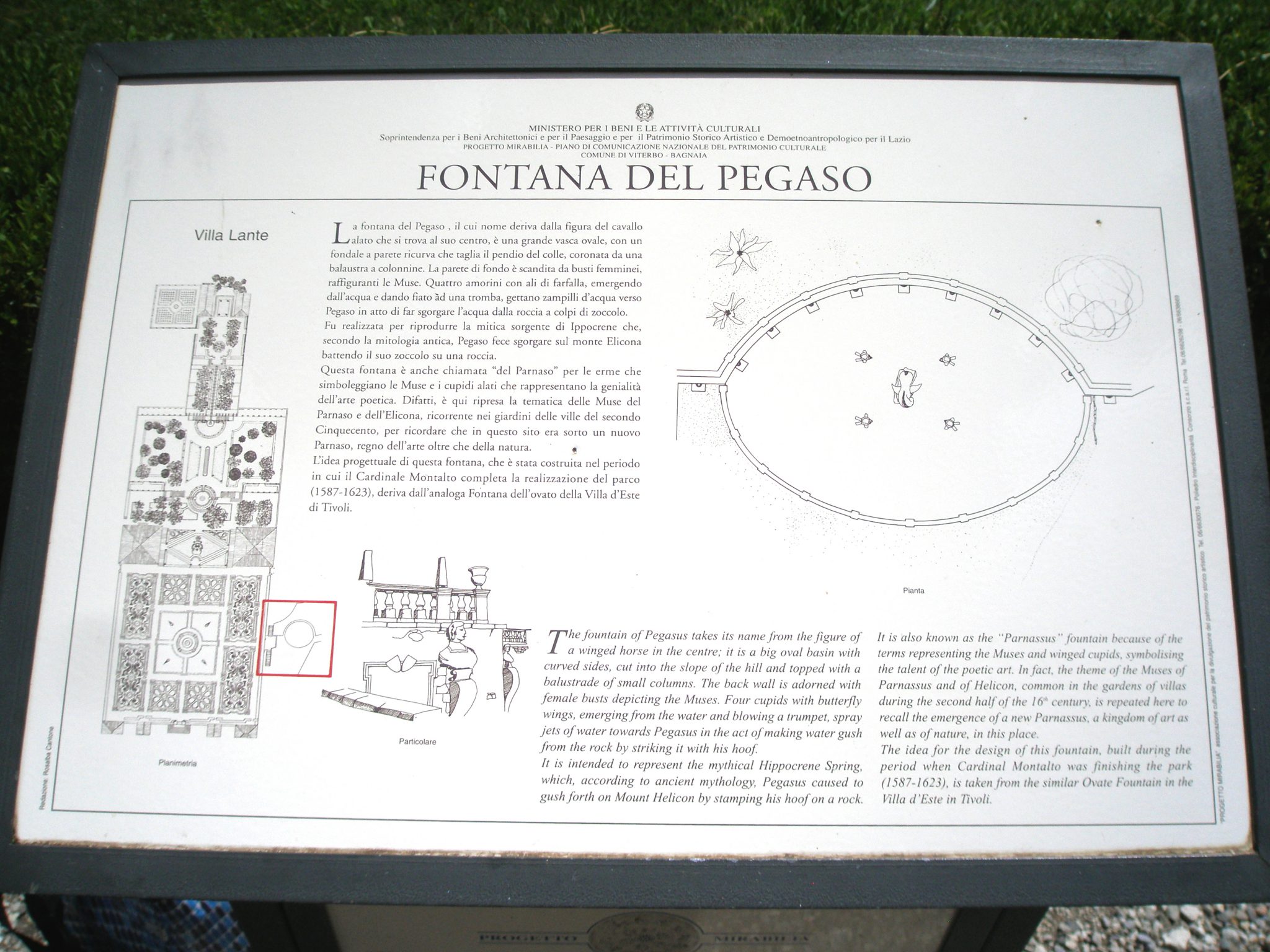

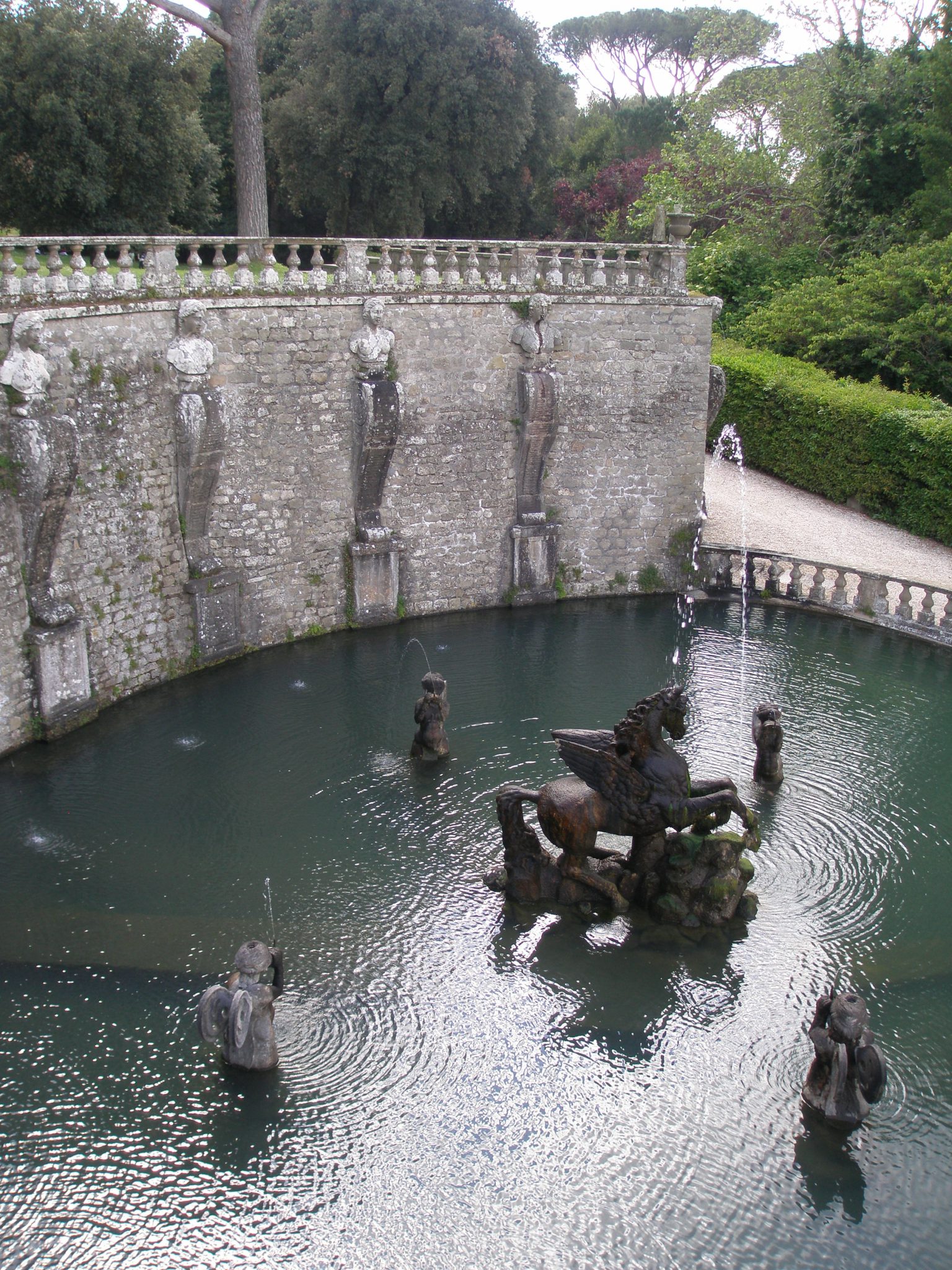

The Pegasus Fountain. The gardens of Villa Lante, in Bagnaia, Italy were begun in 1566. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

But variations in broadly-held opinions about what Man’s relationship with the Natural World should be don’t come out of the Blue. Since the fall of the Roman Empire, the Italian peninsula had been a place of turmoil, where political conflicts, impoverishment, and constant warring were the norm. But the advent of Renaissance concepts changed the assumption that chaos throughout the Land was a given. Alastair Smart has written, “In Florence in the mid 15th century, almost all educated men took the view that a new epoch had begun. The idea that the 15th century in Italy constituted a new age, in which art and scholarship made a fresh beginning by going back to the forms and values of classical antiquity, is not one that has been invented by later writers. It was present in the minds of the men living at the time.”

By the early decades of the 16th century, the transition from Medieval life toward an early version of modern Europe was well underway. The brightest and most privileged men of the time (and YES, there were a few remarkable women thrown into the mix: most notably the formidable Isabella d’Este, who was born in Ferrara, was de facto ruler of Mantua, and later moved to Rome…just in time to experience 1527’s Disaster) …

Leonardo da Vinci’s drawing of Isabella d’Este. Isabella, Marchioness of Mantua, was often called “The First Lady of the Renaissance.” She lived from 1474 until 1539. In 1525 she set up household in Rome, so as to be near to her son Ercole, who became one of the most powerful cardinals of the Catholic Church.

…were certain that by modeling their futures upon the lessons they’d learned from their study and idealization of the cultural achievements of Classical World, a new age of enlightenment would be assured. But The Sack of Rome in 1527 inflicted a body-blow: the sureties of the High Renaissance’s elite—of the politically-potent nobility, church men, philosophers, and artists—were shaken to the core.

“The Sack of Rome in 1527.” Painted during the 1600s by Johannes Lingelbach, a Dutch genre artist who worked in Rome.

When 34,000 mutinous troops of Charles V first occupied Northern Lazio, and soon thereafter breached the walls of Rome – a city with a culture to which those mostly-mercenary troops were innately hostile – a riot of murder and pillage began. Between 6000 and 12,000 Romans were killed. After eight horrific months, the population of Rome had dropped from 55,000 souls to 10,000. Churches and palaces were looted, and ancient treasures destroyed. The savagery of this attack upon the populace, and upon their rich heritage, had more than a little to do with the destruction of the mind-set of the Roman Renaissance. It took an Act of Nature to end the Sack of Rome: the Plague descended, and, finally, the city’s occupiers departed. The ancient view that life on Earth was a precarious and mysterious condition regained its primacy. With this instability began the period in Italian art and architecture known as Mannerist.

The Mannerist Style turned Classical rules of art–about proportion & depiction–upside down. One stone giant thrashes another, at the Sacro Bosco (known as the Sacred Wood, and also as The Park of the Monsters), in Bomarzo. Image courtesy of THE GARDEN AT BOMARZO, by Jessie Sheeler.

My Northern-Lazio-Garden-Dreams were finally realized when I consulted with my friend Valentina Grossi Orzalesi. Through her custom-crafted-tours company, One Step Closer (based in Fiesole, near Florence: www.onestepcloser.net )

Valentina arranged for me to spend a day with one of

Rome’s most erudite guides, Dr. Vannella della Chiesa. And so, early on the morning of May 14th, Dr. della Chiesa, accompanied by her driver Anacleto, collected me and my guest Donn Brous from the Donna Camilla Savelli Hotel in Rome. We set out for what would become a day of driving, hiking, dining, and—most importantly– of seeing astonishing sights.

Dr. Vannella della Chiesa: looking casually elegant on the steps of the Tiempio del Vignola, at the Sacro Bosco, in Bomarzo.

Our charming driver Anacleto: inside a hollow tree at the Fountain of the Deluge, in the gardens of Villa Lante, Bagnaia.

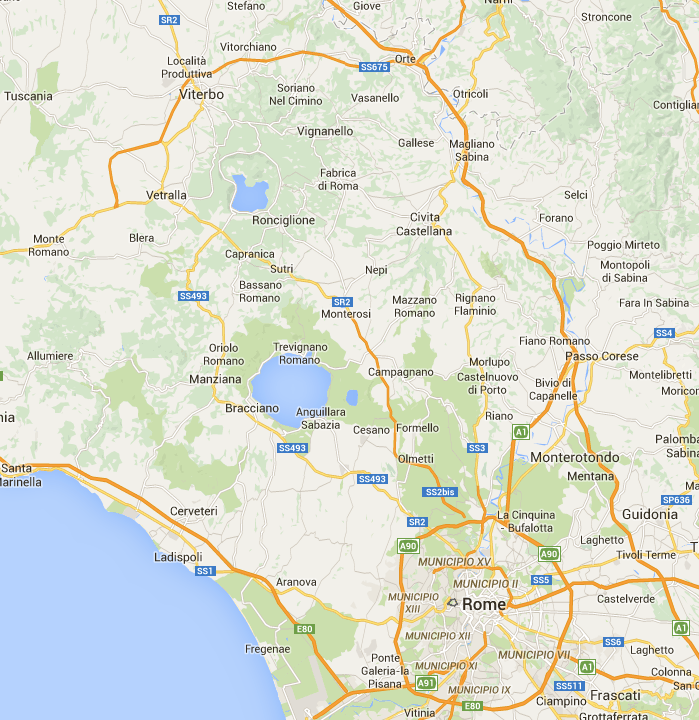

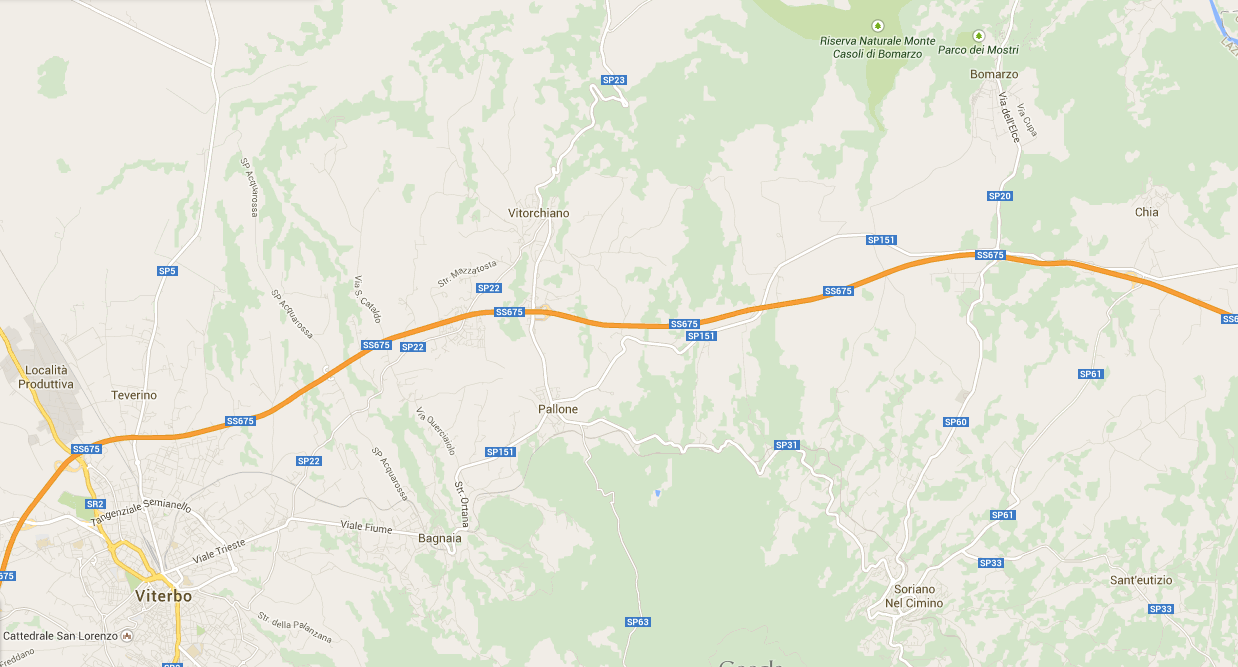

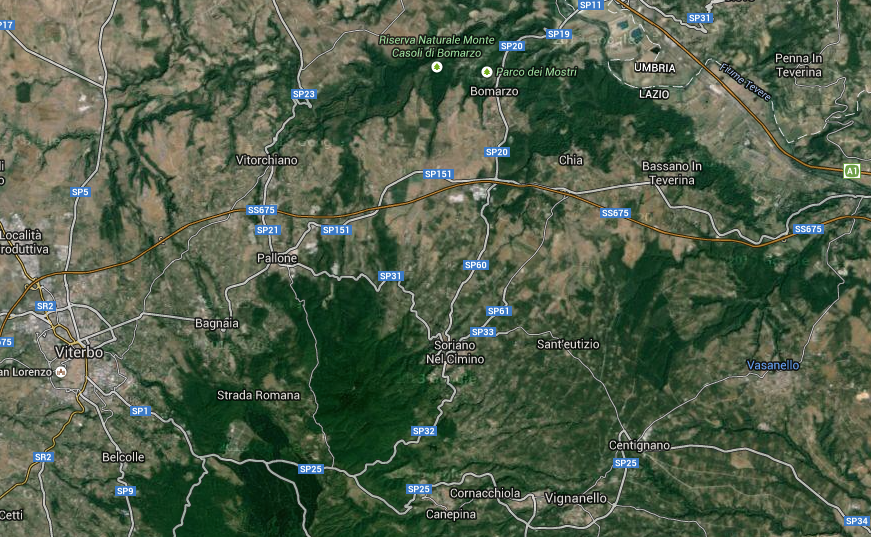

Although driving from Rome to the Viterbo region doesn’t look like much of a trek, my guides wisely estimated that our journey that morning into the hills of Northern Lazio would take us 90 minutes. Breaking free of Rome’s perpetual gridlock of traffic was our first challenge, and an hour later, when we’d exited the A1 Autostrada and entered the Viterbo region, our trip proceeded at a necessarily leisurely pace, as we followed single-lane-wide byways.

The Woodland Gardens of Sacro Bosco are nearly impossible to reach by public transportation. As Anacleto navigated over country roads — which became steeper and narrower and more alarmingly curvaceous as we approached the Village of Bomarzo — I gave silent thanks to Valentina Grossi Orzalesi for connecting me with Dr. della Chiesa, and with Anacleto. Without the help of my three Italian experts, this long-hoped-for day-trip wouldn’t have been happening.

Our first destination: THE SACRO BOSCO

Comune di BOMARZO

( 9 miles east-northeast of Viterbo, and 42 miles north-northwest of Rome )

The Garden is open year-round, from 8:30 until sunset.

Admission: 10 Euros

Garden’s website: www.bomarzo.net

[A note for Fastidious Travelers: bring a roll of toilet paper with

you. The sanitary facilities at Sacro Bosco are—ahem—

somewhat neglected by the Management. Also wear Sensible

Shoes…the paths through the woods are muddy and steep.]

Garden Visit.com provides a good introduction to the Sacro Bosco:

“As pure fantasy, this garden is without equal. It was made in a wood and many of its giant sculptures were carved from living rock. Stylistically, Bomarzo represents a step [from Mannerism ] toward the drama of the Baroque. Poking gentle fun at the egotistical iconography of the Este and the Medici families, it is also a precursor of the English landscape garden. With the elegant taste of a Renaissance duke, Vicino Orsini created features with some resemblance to a modern theme park. But his aims were altogether serious. Orsini was a military captain with literary tastes. He conceived the garden as a Sacred Wood (Sacro Bosco), inspired by the description of Arcadia in Virgil’s AENEID. There is an enormous laughing mask. A moss-covered tortoise supports a statue of fame. A leaning house illustrates the corrupt state of the world. The figures come from Ariosto’s ORLANDO FURIOSO.”

Vicino Orsini was the Duke of Orsino. Bomarzo had long been the historical fiefdom of the Orsini family, whose castle perches at the highest edge of the little hill town. From his castle, Vicino could see the treetops of his Woodland Garden, which he established on the slopes of a damp, forested ravine that’s about a half mile from the Village.

We know that Vicino Orsini was a friend of the great architect and garden designer Pirro Ligorio, and so can be fairly confident that

Ligorio advised Orsini about the overall layout of the garden.

Although Pirro Ligorio may have contributed only superficially to the design of the garden at Bomarzo, we’re certain that he was entirely responsible for the master plan of a nearby garden that belonged to Cardinal Ippolito II d’Este… yet another character in Vicino Orsini’s circle of aristocratic friends. In my next DIARY FOR ARMCHAIR TRAVELERS, we’ll visit Ligorio’s masterpiece: the gardens of Villa d’Este, in Tivoli, which were begun in 1566 (and which are my favorite gardens on the Planet).

But, at Sacro Bosco, the narrative of decorative elements was certainly composed by Vicino Orsini himself. Orsini’s complexities were legendary. Retired soldier. Politician. Poet. Punner. Lover of beautiful women. Pater familias. Guilty husband. Student of the Classics. Our Duke’s brain was full to bursting with ideas about life and death and art. When we stroll through the shaggy remains of the gardens that became his life’s work, what we’re really doing is dipping into the psyche of a Very Interesting Individual.

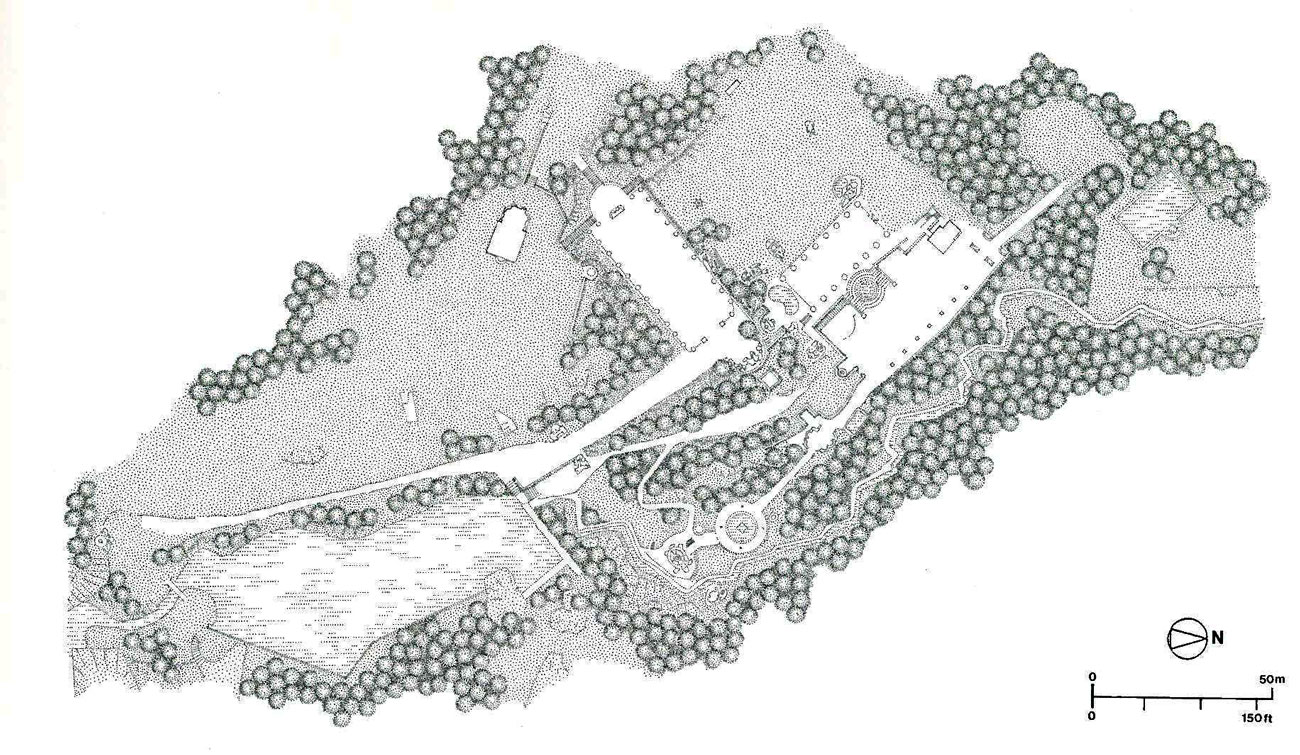

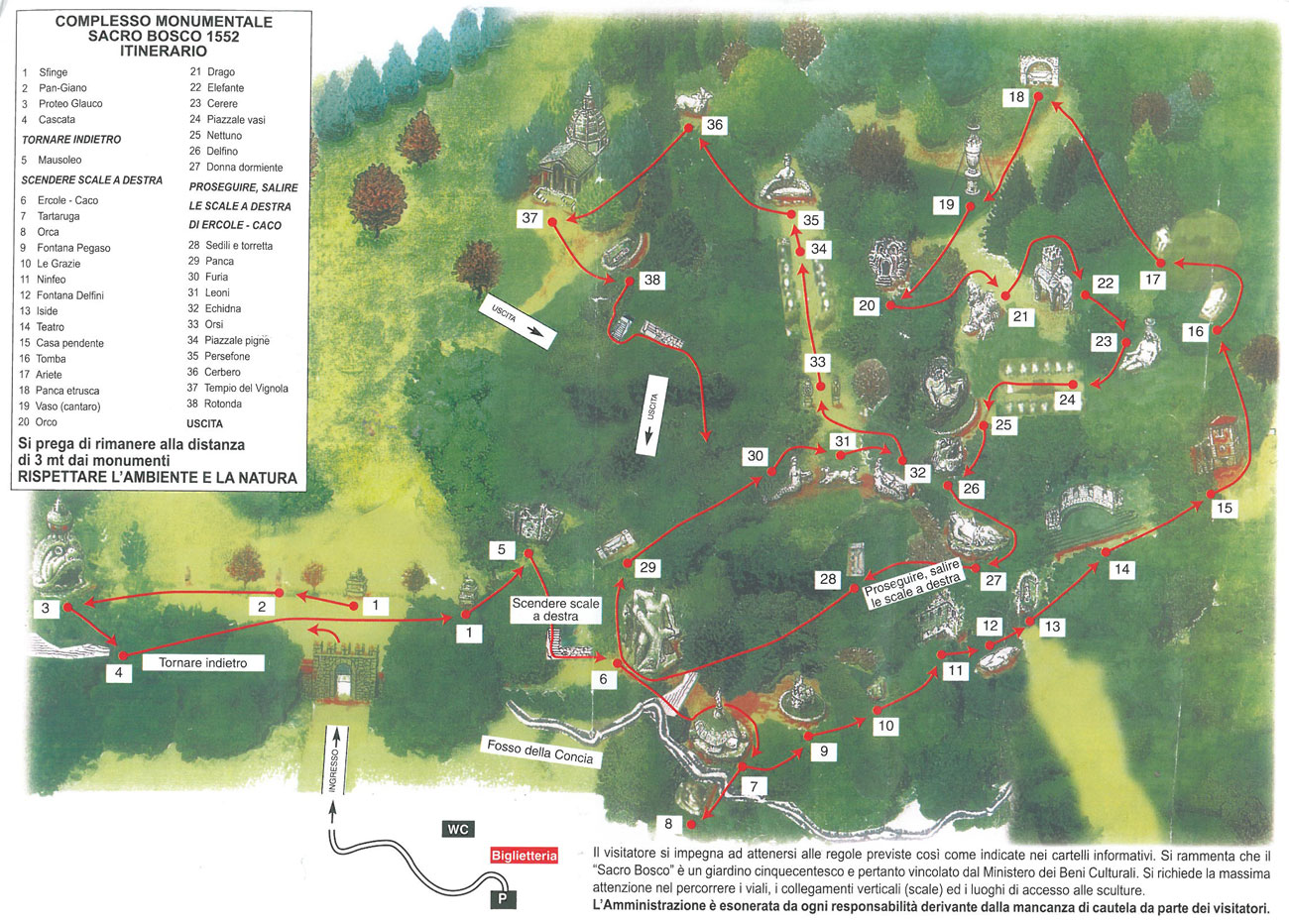

Drawn-to-scale Plan of Sacro Bosco. Image from THE ARCHITECTURE OF WESTERN GARDENS, courtesy of The MIT Press.

Our view of the Orsini Castle, in the village of Bomarzo, as seen from the Gates to the Garden of Sacro Bosco.

Following Vicino Orsini’s death in 1584, the garden he called his “Boschetto” (little wood) immediately began its decline. We do know that in 1604 the large sculptures that adorned Vicino’s Little Wood hadn’t yet become completely overgrown. During that year, the painter Giovanni Guerra visited Bomarzo, and made a series of drawings of the garden’s most striking ornaments. The proof that Orsini’s garden was then forgotten for nearly 350 years is its absence from all of the books that were published, up until 1950, about Italy’s significant gardens. We owe the rediscovery of Sacro Bosco to the enthusiasm of the art critic Mario Praz, who led his good friend Salvador Dali into the thickets that enveloped the Duke of Orsino’s surrealistic sculptures. Dali made a short film about the Garden’s statues, which drew the attention of Jean Cocteau, who in turn sent news of the long-lost wonders of Sacro Bosco out into wider World.

This is a screen grab from the short film showing Salvador Dali at Bomarzo. Here, Dali goes nose-to-nose with the Goddess Demeter.

Apart from our certainty that Orsini placed his fanciful creations in a largely deciduous forest, we have no idea about the varieties of flowers or hedges that may have been added to the landscape. We only know that a copious supply of water was once available to feed the extensive network of Sacro Bosco’s fountains and pools. Unfortunately, that source of water has been long dry, and all of the water features are now vessels for nothing more than moss and lichen. At present, Sacro Bosco’s wild foliage is largely un-pruned, and shafts of sunlight only occasionally pierce the Garden’s dense canopy of leaves.

Now, let’s begin our extended excursion into the wonderful mind –and garden — of Vicino Orsini:

INGRESSO–Entrance

#1 on the Map: DUE SFINGI—Two Sphinxes

A better look at the inscription on the base of Sphinx Number Two. Image courtesy of THE GARDEN AT BOMARZO, by Jessie Sheeler.

Vicino, being properly Classical, arranged for his guests to be greeted by twin Sphinxes, one of whom declares: “You who enter here put your mind to it part by part and tell me then if so many wonders were made as trickery or as art.”

#2 on the Map: PAN-GIANO—Carved Herm

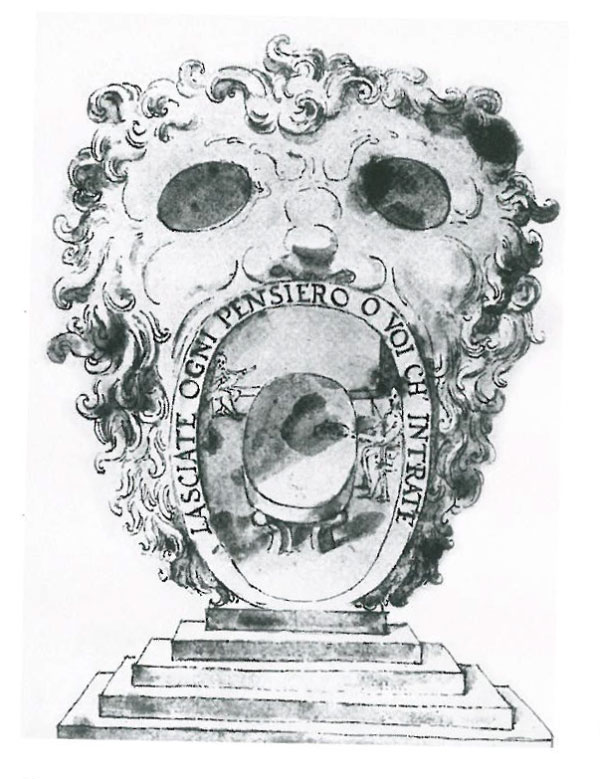

#3 on the Map: PROTEO GLAUCO—Blue-Green, or Glaucous Proteus. Also called “The Mask of Madness”

A closer look at the “Mask of Madness.” Traces of the original color can still be seen on the globe. Many of the statues at Bomarzo were decorated in vibrant colors; the pigments mixed with a secret formula that included milk, and which thus remained unfaded by weather.

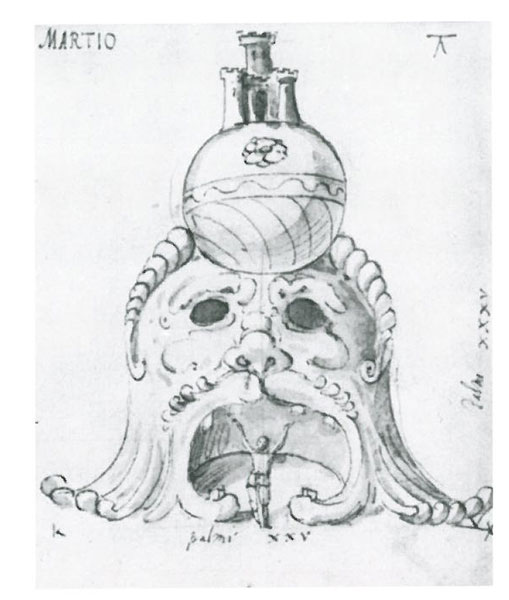

Engraving of the Mask of Madness, by Giovanni Guerra in 1604. Guerra (born 1544, died 1618) was a painter and draughtsman, and lived in Modena. In 1604 he visited the already-beginning-to-be-overgrown gardens at Bomarzo, and did a series of drawings of Vicino Orsini’s fantastic statues.

#5 on the Map: MAUSOLEO—The “Ruined” Masoleum…which was built to look like the eroded remains of a Crypt.

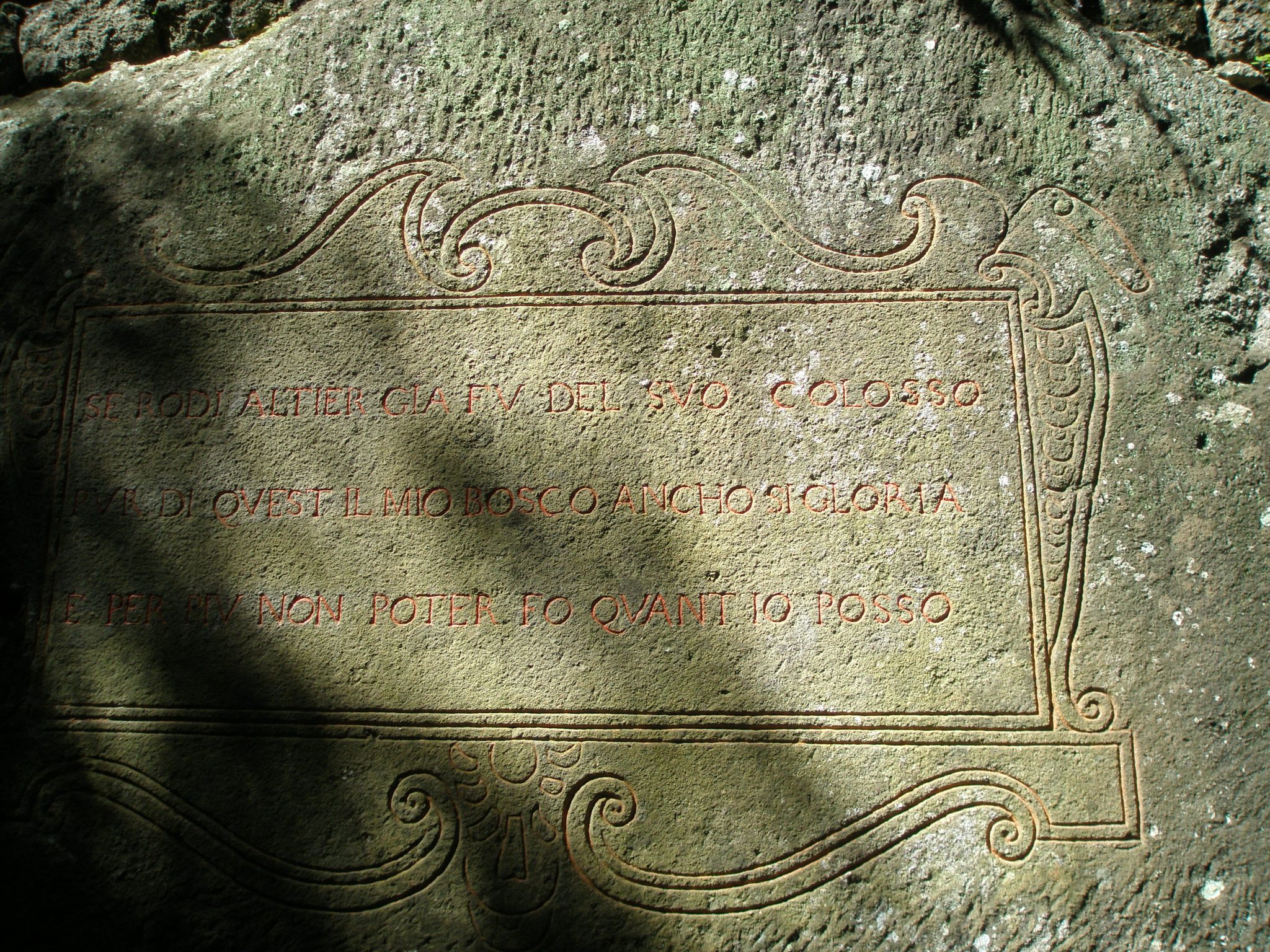

#6 on the Map: ERCOLE & CACO—Hercules Vanquishing the Robber Cacus. Also called’”The Wrestling Colossi”

Another snippet, written by Vicino, accompanies his Wrestling Colossi: “If Rhodes of old was elevated by its Colossus, so by this one my wood is made glorious too, and more I cannot do. I do as much as I am able to.”

#7 on the Map: TARTARUGA—Tortoise carrying the winged figure of Fame, who is balancing upon a sphere. Fame originally was shown blowing a double horn.

This is Vicino Orsini’s illustration of “Festina Lente,” or “Make Haste Slowly.” [Note: I am considering using this image to illustrate my last name. Fame….not important. But the concept of Making Haste Slowly? That’s a Good Idea….]

#8 on the Map: ORCA—Whale’s Mouth

View from above of The Tortoise, and the nearby Whale’s Mouth. Image courtesy of THE GARDEN AT BOMARZO, by Jessie Sheeler.

#9 on the Map: FONTANA PEGASO—Fountain of Pegasus

#10 on the Map: LE GRAZIE—The Three Graces

#11 on the Map: NINFEO—The Nymphaeum

My view from a higher level of the gardens, down to the terrace and bench that are opposite the Nymphaeum & The Three Graces.

#12 on the Map: FONTANA DELFINI—Fountain of the Dolphin

#13 on the Map: ISIDE—The Grotto of Isis

Approaching the Grotto of Isis, we encounter the giant head of Jupiter Ammon. Water once streamed from Jupiter’s mouth; Jupiter was thought to have the power to grant– or to withhold — the rain.

#14 on the Map: TEATRO—The Theatre

A view of the Theatre, from above. The Leaning House is in the background. Image courtesy of THE GARDEN AT BOMARZO, by Jessie Sheeler.

#15 on the Map: CASA PENDENTE—The Leaning House

My companions felt seasick while inside the Leaning House, and so exited quickly. I remained in the House…my good sea legs kept me steady.

#16 on the Map: TOMBA—Tomb (yet another of Vicino’s ersatz graves)

#18 on the Map: PANCA ETRUSCA—Etruscan Bench

#19 on the Map: VASO—Giant Vase

#20 on the Map: ORGO—Ogre, also known as “The Mouth of Hell”

#21 on the Map: DRAGO—Dragon

A Dragon, being attacked by Lions. Dragons typically represented Satan, while Lions are regarded as noble beasts.

View of Dragon & Lions, with the Square of the Vases in the background. Image courtesy of THE GARDEN AT BOMARZO, by Jessie Sheeler.

The Dragon & Lions are in deep shade, while an Elephant balancing a Tower on its back is bathed by sunlight.

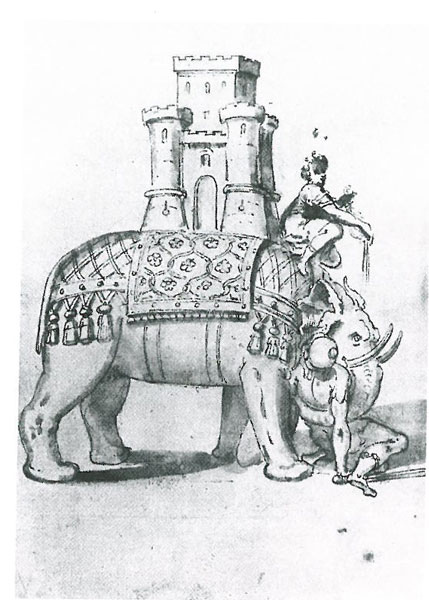

#22 on the Map: ELEFANTE—Elephant balancing a tower, and carrying a dead warrior in his trunk, while being ridden by another soldier.

Elephants bearing castles were a frequently-used image in Renaissance art, as Hannibal’s use of elephants to invade the Italian peninsula was recalled. And, from time immemorial, elephants have also represented strength and restraint…along with memory.

#23 on the Map: CERERE—The Goddess Demeter

And a tiny child clings to Demeter’s neck. Image courtesy of THE GARDEN AT BOMARZO, by Jessie Sheeler.

#24 on the Map: PIAZZALE VASI—Square of the Vases

Every Giant Vase is inscribed with a message from Vicino. This one says: “Night and Day we are vigilant and ready to protect this fountain from any harm.” No evidence survives of fountains in this part of Sacro Bosco. I’m trying to imagine what the gardens were like, when every corner was filled with the sounds of splashing water.

#25 on the Map: NETTUNO—Neptune

#26 on the Map: DELFINO—Dolphin’s Head

Neptune is kept company by a Jolly Dolphin. Image courtesy of THE GARDEN AT BOMARZO, by Jessie Sheeler.

#27 on the Map: DONNA DORMIENTE—Sleeping Woman, guarded by her Dog.

#30 on the Map: FURIA— A Siren with double tails, which serve as garden benches

#31 on the Map: LEONI—Lions

A Lion & Lioness rest, between the Two Sirens. Image courtesy of THE GARDEN AT BOMARZO, by Jessie Sheeler.

#32 on the Map: ECHIDNA—The second Siren has a Classic Harpy Configuration, with the head and trunk of a woman, and the tail, wings and talons of a bird.

#33 on the Map: ORSI—Two Bears stand guard, as they embody and also do some punning upon, Vicino’s family name. “Orsini” in Italian means “Little Bears.”

#34 on the Map: PIAZZALE PIGNE—Square of the Pine Cones

Square of the Giant Pine Cones. During Orsini’s era, acorns were symbols of the Golden Age, whereas pine cones were symbols of Death.

And another message from the Duke of Orsino: “Memphis and every other marvel too that the world has held in honor until now yield to the holy wood, which is only like itself and nothing else.” Indeed!

#35 on the Map: PERSEFONE—Persephone

Persephone is at the opposite end of the Square of the Pine Cones. She provides another shady resting spot.

#36 on the Map: CERBERO—Cerberus

#37 on the Map: TEMPIO DEL VIGNOLA—Temple of Vignola

A high wall encircles the entire Garden. This Gate separates the meadow by the Temple from the wilderness of the Bomarzo hills.

#38 on the Map—ROTONDA—The Rotunda

As we made our way to the Uscita (Exit), we passed these boulders, which were entirely covered with velvety blankets of Sedum and Moss:

It’s all too easy to fixate upon Bomarzo’s details; to become a connoisseur of its complexities. The hunt for the Meanings of the Duke of Orsino’s sculptural creations is irresistible. But, to truly absorb the essence of Vicino Orsini’s Boschetto, we should set aside our rational thoughts, and instead accept that we’re temporarily inhabiting the dream world of a Most Singular Gentleman. The schoolchildren who are brought by their teachers to the Sacro Bosco know exactly how to experience the place. They do not try to decipher the carved inscriptions, or to parse the symbolism of the giant sculptures. Instead, they open eyes wide, laugh, and then run pell-mell, in a fever to see more and more and more of the surprises that await, behind every thicket, and around every bend of the shady pathways.

The Mouth of Hell: illuminated at night…to make us Shiver With Excitement! Image courtesy of the Sacro Bosco Garden in Bomarzo.

Before heading to nearby Bagnaia, and the gardens of Villa Lante, Vannella asked Anacleto to make a detour into the village of Bomarzo itself, and so he maneuvered his vehicle up impossibly narrow and steep streets, to a parking lot just below the Orsini Castle. These were our views:

The Sacro Bosco Garden and its massive statues are tucked into the fold of a narrow valley…and completely hidden from view by the band of greenery at the center of this photo.

Next, to Bagnaia, and the gardens of Villa Lante.

Aerial view of the Gardens of Villa Lante (foreground), and the Village of Bagnaia (background). Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

We were all famished, and so taking a lunch break was imperative. Vannella led us to the restaurant adjoining the B&B da Peppe al Borgo (#23 Cardinal de Gambara, Bagnaia 01100 , Italy ) where we feasted…and feasted (pace yourselves: the servings are enormous). If you visit Villa Lante, be sure also to make time for a meal at this Café, which serves dishes that are particular to Northern Lazio…many of which you’ll never find on the menus of Roman eateries.

Onward, to our Second Garden of the Day:

Villa Lante Gardens

in the Village of Bagnaia

(Bagnaia is a bit over 3 miles to the East of Viterbo, on Route 205 )

The Ticket Office for the Gardens is located at the end of Via Jacopo Barozzi.

Admission Fee: 5 Euros

The gardens are open year-round, from Tuesday through Sunday, but are closed on all Italian holidays

Garden Website

https://www.grandigiardini.it/lang_EN/giardini-scheda.php?id=67

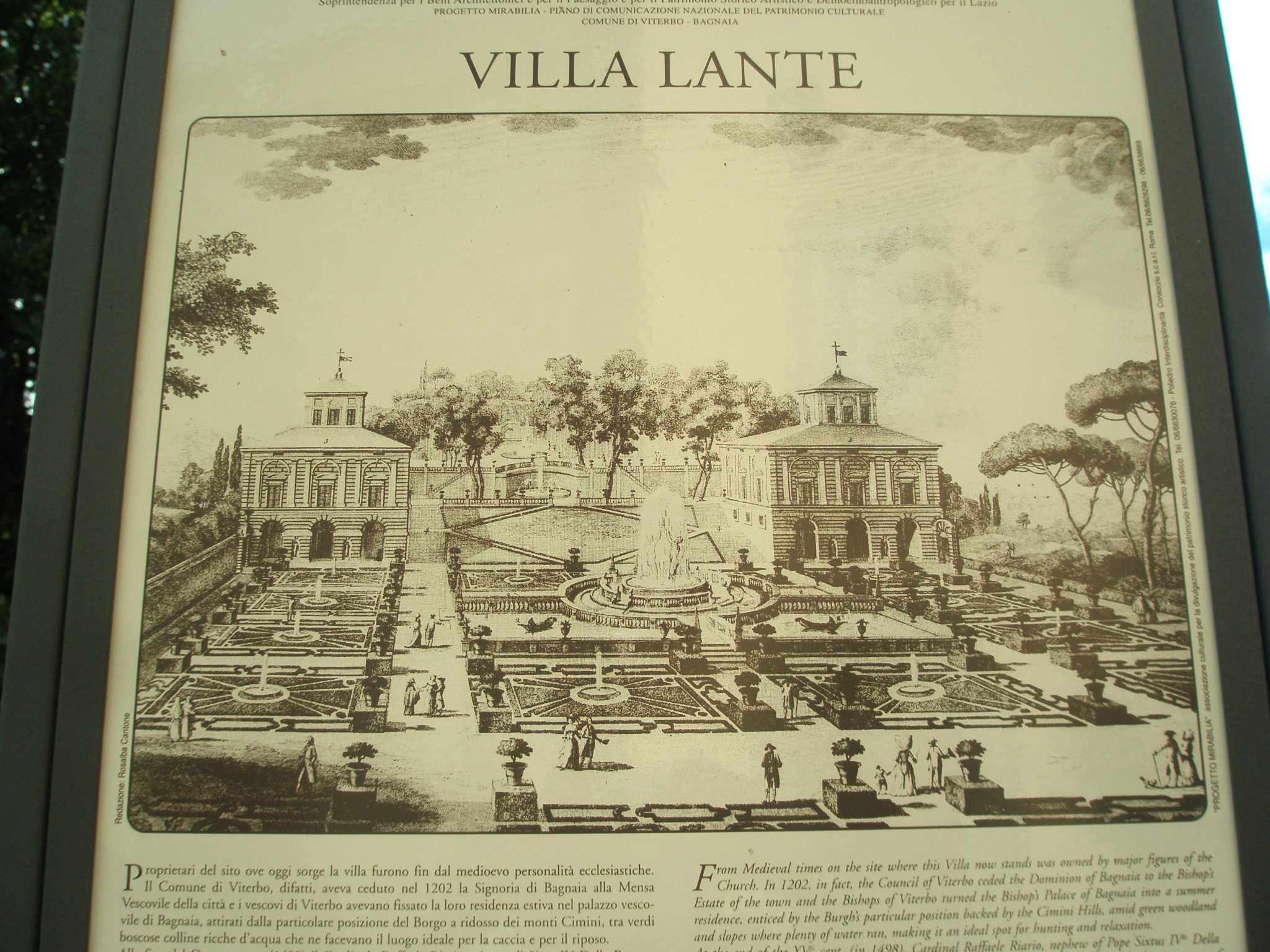

Our visit to Villa Lante’s gardens begins. The gardens at Villa Lante have been long been a Goldmine for Scholars of Garden Design…but, unfortunately, the definitive tome—all 512 pages written by Fritz Barth—has only been published in German. And the Visitor’s Guides to the gardens, exclusively distributed by the Il Pegaso Bookshop which is just outside the gates to the garden, are available in several editions, but none have yet been done in English. During my May 2014 chat with the owner of the Bookshop, he indicated that he hopes to someday also make an English-language guide available. However, several brief, English overviews of the gardens HAVE been written…by Marella Agnelli, by Bruno Adorni, and by that British-gardening-gadabout, Monty Don (who I was fortunate enough to meet at the 2014 Chelsea Flower Show, in London, when he admitted to me that the current management of the gardens at Villa Lante could be greatly improved). As introduction to the gardens at Villa Lante, Monty Don’s summary, now quoted in part from his book GREAT GARDENS OF ITALY, will serve us well:

“Villa Lante is not the first great Renaissance garden to be made [my note: more accurately, Villa Lante should be classified as a Late Renaissance, or a Mannerist garden], nor the biggest, most expensive or most innovative in design. Its creator, Cardinal Gambara, was not even the most important or powerful figure in the Viterbo area, let alone the Catholic Church of the mid-16th century. It is not a garden whose code has to be unlocked to be appreciated. It does have, as all gardens of its period did, a number of symbols and images that would have been potent statements and messages for contemporary visitors, but you do not need to understand any of this to enjoy the garden to the full. Yet it is, as far as any man-made construct might be, almost perfect.”

“In 1566 Cardinal Giovan Francesco Gambara, related by marriage to the Farnese family…and close friend of Cardinal d’Este at Tivoli, as well as his neighbor Vicino Orsini at Bomarzo, was appointed Bishop of Viterbo, and it was he that turned a section of [a hunting] park into the garden that we see now.”

Monty Don concludes: “It has a sureness of touch, a completeness that no other Italian garden possesses. It is small enough to see every inch of and to hold in one’s mind, yet impressively grand enough to soar in the imagination. It is, without question, a masterpiece.”

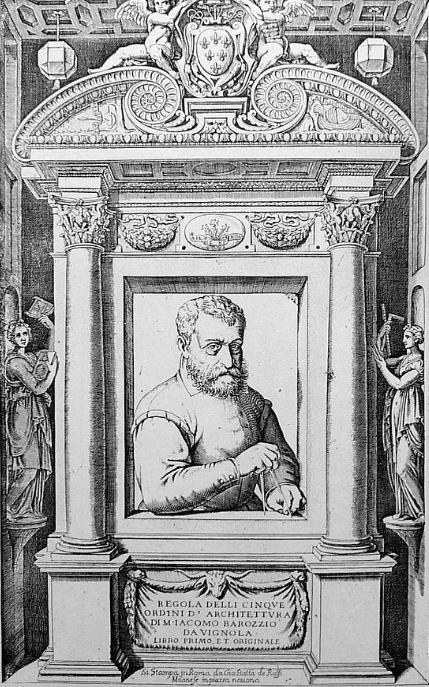

Unlike the vivid dreams which Vicino Orsini dramatized in his Boschetto at Bomarzo, Cardinal Gambara’s garden isn’t an overtly autobiographical creation. Instead, the Cardinal turned to a committee of the best architects, garden-designers, and hydraulic engineers of the Day. Architect Giacomo Barozzoi, more commonly known as “Il Vignola,” conceived the master plan, and built a series of terraces, which he organized along a central north-south spine of flowing water, which cascades down a hillside. Our very busy friend Pirro Ligorio was summoned to contribute ideas about adding elements of surprise, such as hidden fountains. And Thomaso Chiruchi, a hydraulics specialist, made sure that the water that moved through the elaborate network of rills and pools and fountains performed as intended.

Architect Giacomo da Vignola—aka Il Vignola (born 1507, died 1573)—was responsible for the master plan of the gardens of Villa Lante

On the afternoon of May 14, 2014 when I explored Villa Lante, the weather, which during our morning hours at the gardens of Bomarzo had been fair, became

temperamental. Our visit began under blue skies. But shortly, a hazy overcast prevailed. Soon, dark clouds gathered, and not long after, fat raindrops pelted us. Finally, almost as if Italy was mimicking the mercurial climate of England, golden sunlight reappeared. This made my job as garden-photographer difficult, and so I’ll inject a smattering of sunny-day photos (all courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop) into my sequence of cloudy-day pictures.

We approach the high wall that surrounds the gardens of Villa Lante. This wall was built in 1514, to enclose a 62-acre hunting preserve which was the summer playground for the various Bishops of Viterbo.

Just as Vicino Orsini used images of Bears in his woodland garden at Bomarzo, Cardinal Gambara’s gardens at Villa Lante include much visual-name-punning about “Gamberi”…or “Crayfish.”

When a Mannerist garden-maker had a surname that recalled an animal — or a crustacean — this was occasion for much humor and commotion. God forbid that a garden-maker had NOT possessed a name that was also useful for word-play!

Engraving of Villa Lante, by G.Lauro, done in 1612–1614. Image from THE ARCHITECTURE OF WESTERN GARDENS, courtesy of The MIT Press.

But, before we enter the Gardens Proper, we encounter Pegasus.

A closer look at the Pegasus Fountain. Above the Fountain, the 2nd story and cupola of one of the Garden’s two pavilions is visible.

We climb, up toward the Main Garden.

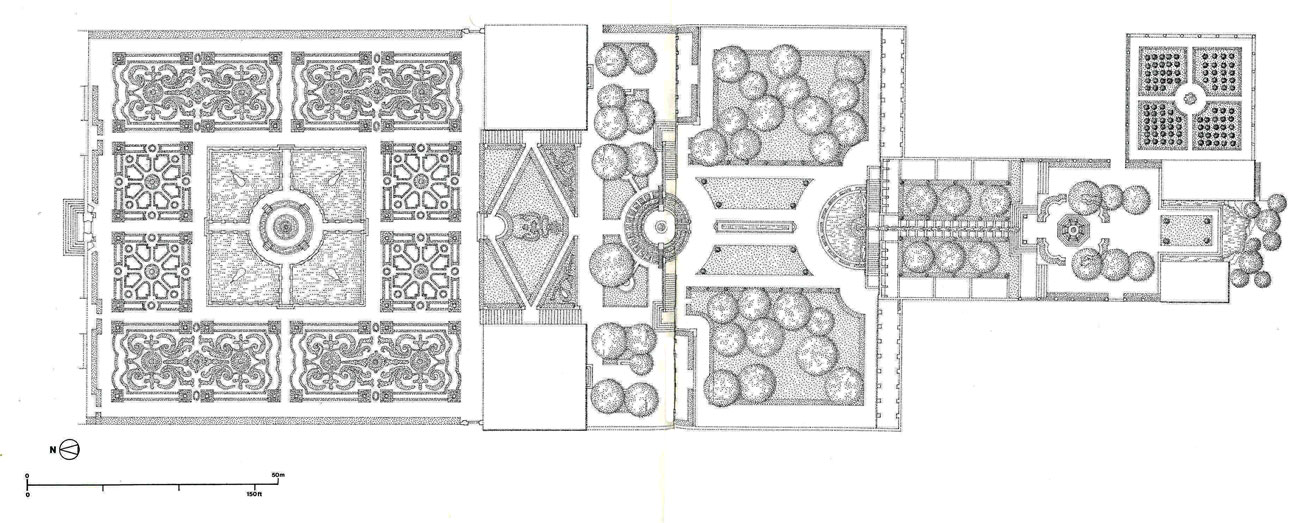

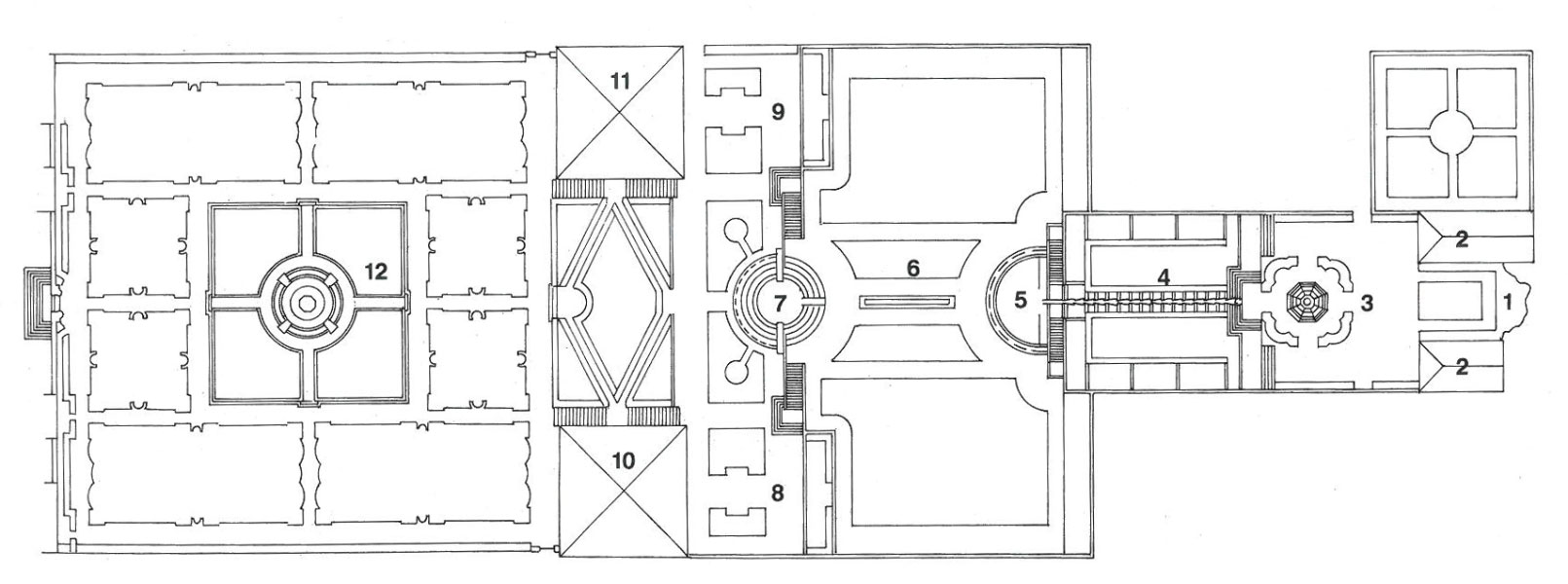

Drawn-to-scale MAP of the Main Gardens at Villa Lante. Image from THE ARCHITECTURE OF WESTERN GARDENS, courtesy of The MIT Press.

KEY to the Garden Areas at Villa Lante. Image from THE ARCHITECTURE OF WESTERN GARDENS, courtesy of The MIT Press.

The Main Garden has twelve sections.

#1: Fountain of the Deluge (Grotto)

#2: Houses of the Muses

#3: Fountain of the Dolphins

#4: Water Chain

#5: Fountain of the Giants

#6: The Cardinal’s (Water) Table

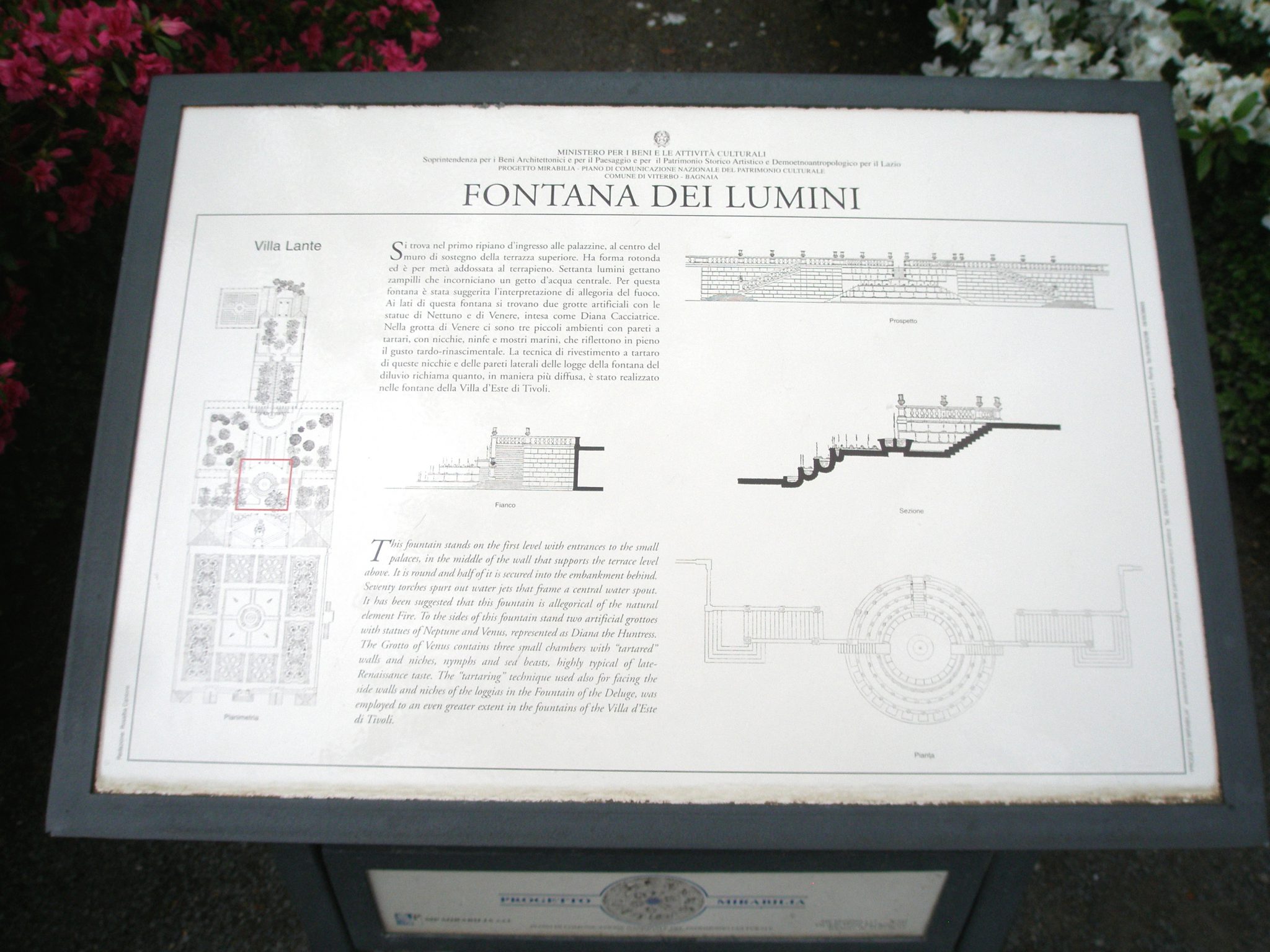

#7: Fountain of the Lights (or Cave)

#8: Grotto of Venus

#9: Grotto of Neptune

#10: Palazzina Gambara

#11: Palazzina Montalto

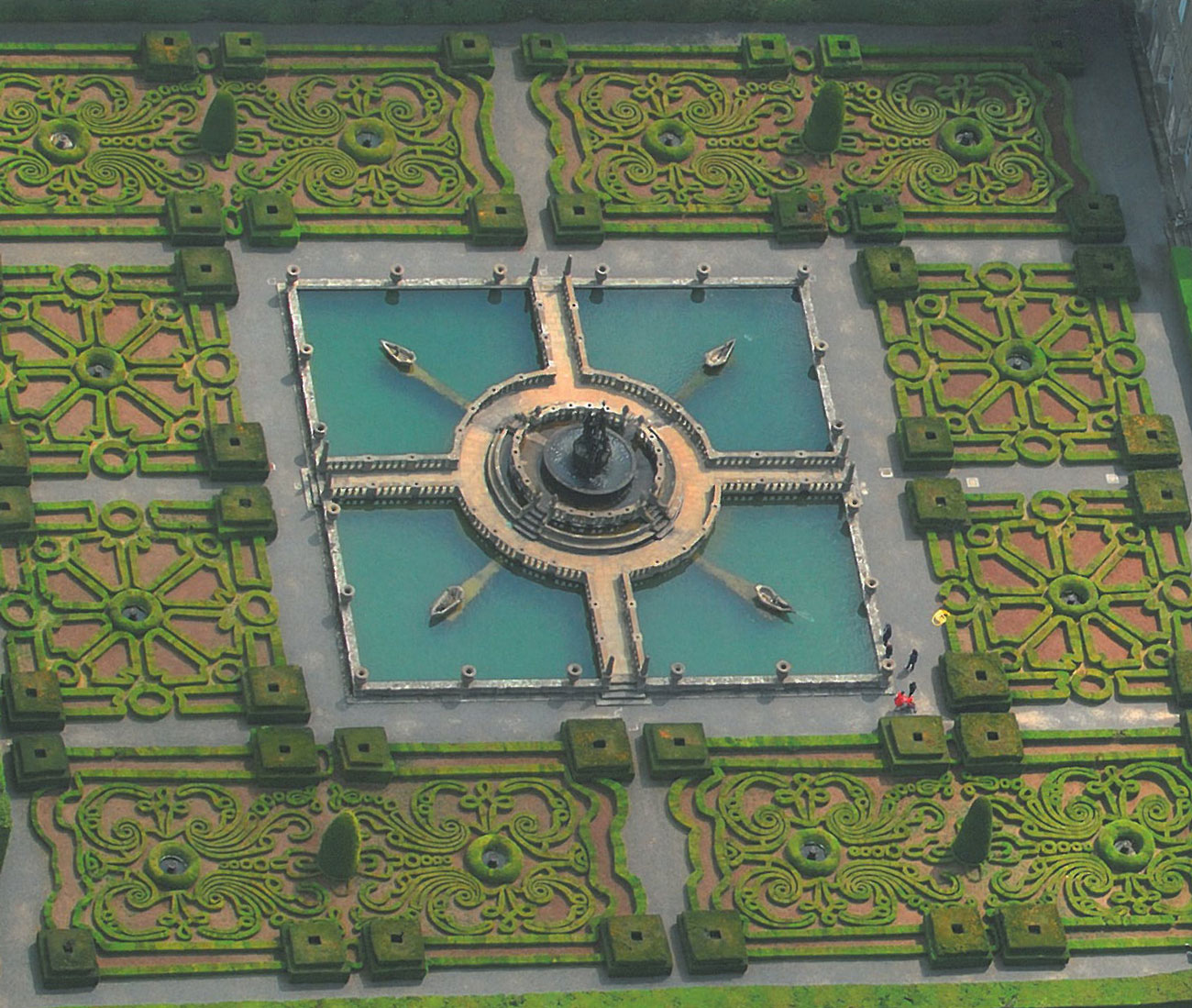

#12: Fountain of the Moors (Water Garden surrounded by extensive knot gardens)

Area #12 is on the lowest level of the gardens. Area #1 is at the highest level. Visitors currently are directed to enter the gardens at the bottom of the hill, where they begin their garden walks by the Fountain of the Moors. But this sequence REVERSES the order in which Vignola intended the areas of the gardens to be discovered.

During Cardinal Gambara’s time, his visitors began their garden perambulations by the rustic and vine-covered Grotto of the Fountain of the Deluge, at the top of the hill. As Gambara’s guests proceeded down through the garden, they followed the course of a stream which was channeled through various garden structures and which fed increasingly elaborate fountains, until they ended their wanderings at the severely-geometric water garden named the Fountain of the Moors. The sounds of water as it splashes against rock and cascades down rills and sprays from fountains pervade a visitor’s senses. This tension between the dynamism of moving water and the immobility of the stones which Gambara’s masons carved to direct the downward flow of the stream provides the dialogue—both visual and aural— for this particular garden. Being a Mannerist-era design, the detailing of the garden’s ornaments are often surprising. A long Rill, with edges composed of stone carvings that replicate the legs of hundreds of crayfish (yet another pun on the name of the garden’s owner), directs rapidly-gushing water toward a long, stone table, where a central channel of languidly-flowing water provided a setting for elaborate banquets. Platters of delicacies were floated along the stream, put there to be snatched by Gambara’s hungry guests. Ahhh….’twas good to be a Cardinal!

In the spirit of living, for just a little while, like guests of this particular Cardinal, we’ll take a stroll through his gardens. But we’ll pretend that we’ve been declared Very Special Visitors, and are thus allowed to encounter his garden areas in their intended sequence…from top to bottom. We’ll first climb toward the highest point of his property, and through the parklands which were once a hunting preserve.

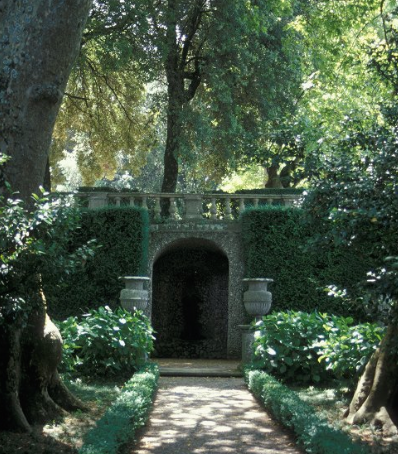

IL PARCO

The Parklands at Villa Lante. From the highest point of this Park, we’ll soon enter the Gardens Proper, through a gate which leads to the Fountain of the Deluge. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

#1 on the Map: FOUNTAIN OF THE DELUGE, & #2 on the Map: THE HOUSES OF THE MUSES

Two little Temples, called the Houses of the Muses, flank the Fountain of the Deluge. We’re at the top of the hill. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

The Grotto of the Fountain of the Deluge. The water supply for the entire Garden issues from the Grotto.

#3 on the Map: FOUNTAIN OF THE DOLPHINS

The Fountain of the Dolphins was once enclosed with a wooden trellis, which was covered with vines. Joke fountains were triggered by the movements of passers-by….step on the wrong stone, and you got soaked.

#4 on the Map: WATER CHAIN

My view of the distant Village of Bagnaia, from the top of the Water Chain. Half-way down the slope, you can see a portion of the Cardinal’s Table.

And now, a view UP the Water Chain. To take this photo, I paused, about a quarter of the way up from the bottom of the chain.

Two Obelisks mark the lowest point of the Water Chain. Directly below the balustrade is the Fountain of the Giants (or Rivers).

#5 on the Map: FOUNTAIN OF THE GIANTS (or RIVERS)

A sudden squall soaks Donn and Vannella, who’re patiently waiting while I take photos at the Fountain of the Giants.

#6 on the Map: CARDINAL’S TABLE

We’re at the northern-most end of the Cardinal’s Table. In the background: The Fountain of the Giants.

Here’s where the water exits the Cardinal’s Table. At this point, water enters an underground pipe, which then feeds the Fountain of the Lights.

#7 on the Map: FOUNTAIN OF THE LIGHTS (or of the Cave)

My view from the Fountain of the Lights, down across the Fountain of the Moors, and then to the Village of Bagnaia.

#s 8 & 9 on the Map: GROTTOES OF VENUS, AND OF NEPTUNE

The Grotto of Neptune. In both of these nearly-identical grottoes, the statues of their Name-Gods have been long-since removed.

JUST BELOW THE FOUNTAIN OF THE LIGHTS:

Donn heads toward the triangular parterres of boxwood which separate the Palazzina Gambera (seen in the background) from its twin, the Palazzina Montalto.

The Triangular Parterres, viewed as I stood among the much-curvier boxwood hedges that surround the Fountain of the Moors.

#s 10 & 11 on the Maps: PALAZZINA GAMBARA & PALAZZINA MONTALTO

The land upon which the gardens were built had long been used as a summer residence by the various Bishops of Viterbo. Due to the fleeting nature of the Bishops’ occupancies, relatively “simple” structures were required to house them. Thus, both the Palazzina Gambara, and its twin Palazzina Montalto, are small. Each consists of a garden-level loggia used for entertaining, with an apartment on the upper floor.

Palazzina Montalto (on the left) and Palazzina Gambara (on the right), as viewed from within the boxwood parterres that surround the Fountain of the Moors.

Sunny-day view of the Central Fountain in the Fountain of the Moors Garden, with the Palazzina Montalto, and the Palazzina Gambara in the background. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

Another sunshiny view of the two garden pavilions, seen from within the parterres of the Fountain of the Moors Garden. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

Oddly, interior photography is allowed at the Palazzina Montalto, but prohibited at the Palazzina Gambara. These little party pavilions are named for the various Cardinals who commissioned them. Cardinal Gambara’s “casino” was erected in 1578. His successor, Cardinal Montalto, completed a twin garden pavilion

in 1590. The ground-level loggias of both pavilions are decorated with exquisite frescoes which cover the walls and ceilings.

First, my photos of the interior of the Palazzina Montalto:

Now, Il Pegaso Bookshop’s photos of the interior of Palazzina Gambara:

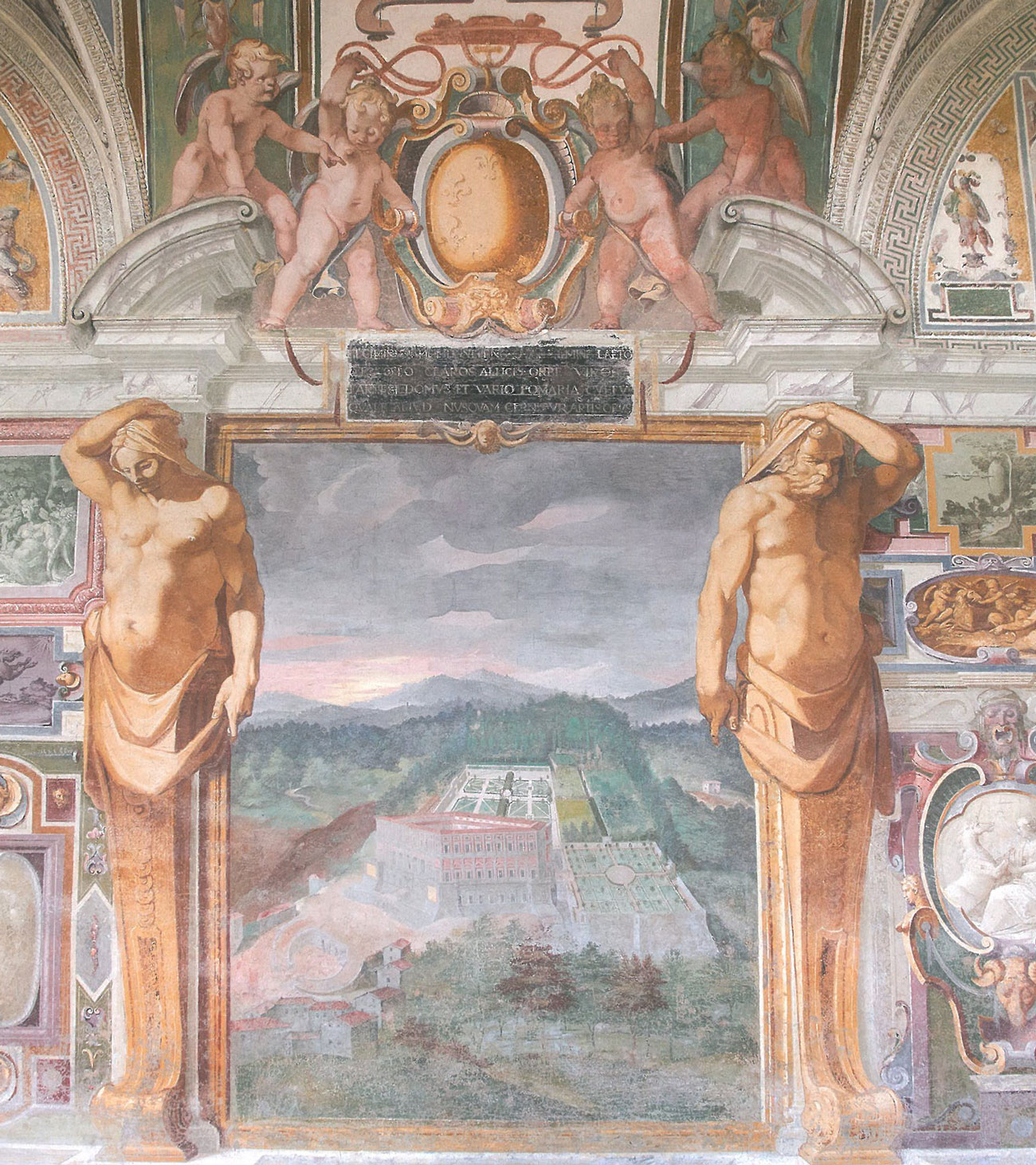

Palazzina Gambara Loggia. A depiction of the gardens of Villa Farnese, in nearby Caprarola. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

Palazzina Gambara Loggia. A fresco of Villa Lante’s own gardens. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

#12 on the Map: THE FOUNTAIN OF THE MOORS (or the WATER SQUARE ), with elaborate boxwood parterres, surrounding the water garden

A sunny-day view of the Fountain of the Moors, as seen from the triangular parterre garden that’s between the Palazzina Gambara and the Palazzina Montalto. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

In better weather: the figures on the Island in the Fountain of the Moors garden. In the background is a gate, beyond which is the Village.

Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

The ubiquitous Gambara Crayfish, on a bridge to the Island in the Fountain of the Moors water garden.

This path, on the east side of the Water Garden, leads to the Gate between the garden and the Village

My view through the bars of the locked Gate, which separates the Fantasy of the Garden, from the Reality of the Village.

Curlicues Galore, on a sunny day, in the Fountain of the Moors gardens. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

View of the Fountain of the Moors gardens, as seen from the cupola of the Palazzina Gambara. Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

I swear…the Birds have got the best views of all, at the gardens of the Villa Lante.

Image courtesy of Il Pegaso Bookshop, in Bagnaia.

Following our hours in Cardinal Gambara’s pleasure-gardens, we ducked into Il Pegaso Bookshop, where I was surprised at the dearth of English-language documentation about Villa Lante. Nevertheless, I was overjoyed to acquire their Italian-language booklet, with all of its beautiful, sunny-day photos.

Using my primitive but effective Italian communication skills (which consist of scribbled drawings, many Pleases and Thank-yous, along with Nouns aplenty…but with absolutely no Verbs, because conjugations would intimidate me into complete Silence), the Bookshop’s owner (who speaks little English)

managed to make me understand how distraught he has become about the relatively small number of visitors—both foreign AND Italian–who make an effort to visit Villa Lante. I sympathized, and told him that, apart from groups of schoolchildren (both at Villa Lante, and in Bomarzo’s Sacred Wood), my companions and I had that day encountered very few other visitors during our garden walks.

Donn inspects the goods. Il Pegaso Bookshop is

located near the Gates to Villa Lante, on Via Jacopo Barozzi, in Bagnaia

This same worry about the meager stream of tourists into Town was also expressed to me by the owner of the Café on Bagnaia’s central Piazza, where we’d enjoyed our lunch. Granted, using public transportation to travel from Rome to Northern Lazio isn’t a practical option, but considering the two World-class gardens in the area, planning a little trek to Bomarzo, and then to Bagnaia, is well worth an investment of time and money.

And so, what to make of our Day’s two very different gardens….gardens which were created more or less simultaneously by erudite men who had decades and fortunes to devote to the process? Bomarzo’s mysterious decorations and somewhat disorienting landscape, and Villa Lante’s operatic waterworks and highly-geometric structure, were clearly created in fevers of artistic expression. Those fevers were further heightened by the spirit of competitive garden-making which had come alive in Italy during the Renaissance. Both Vicino Orsini and Cardinal Gambara were clear about their intentions to make gardens with wonders which would astonish their visitors. But the end results show us the polar extremes of the Mannerist era.

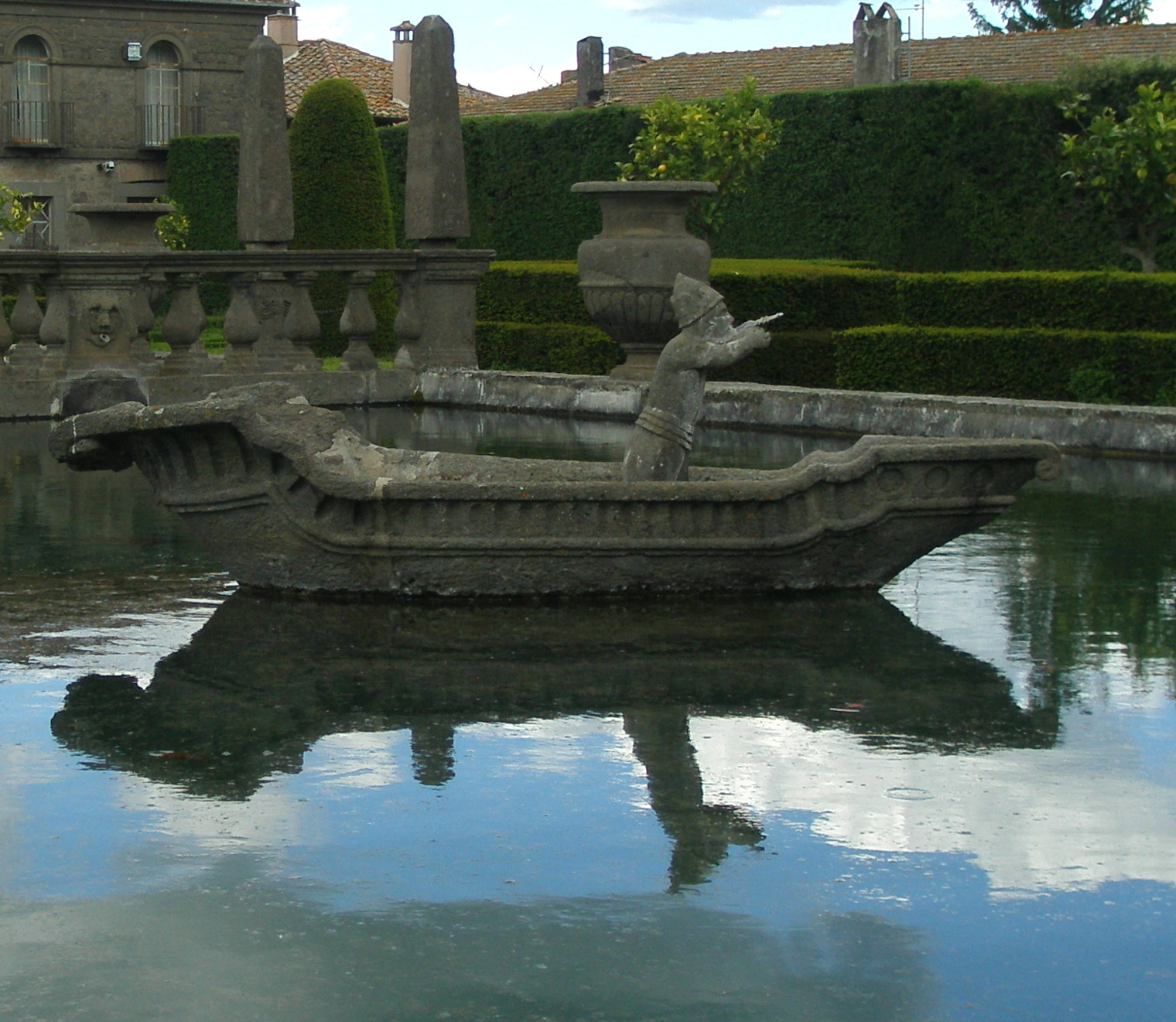

At the Gardens of Villa Lante, architect Vignola still had one design-foot planted firmly and conservatively in the Renaissance. After all, he was designing a highly-visible garden: a showplace for a Cardinal, and by extension for the Church itself. But Vignola’s other design-foot had already begun to mosey over into the Mannerist Realm. While observing the conventions of Renaissance garden-design, where Man’s dominion over Nature’s Chaos was asserted via the rigors of geometry and the wonders of hydraulic technology, Vignola nevertheless was peppering his gardens with visual flourishes that were grotesque and fanciful. Nary a statue in the gardens at Villa Lante is vaguely Classical or Ecumenical in appearance. Giant, roughly-hewn River Gods lounge in splashing waters. Boats made of stone, which should surely sink, instead float serenely upon the surfaces of reflecting pools. Fountainheads and Urns and Herms abound…all decorated with the faces of imps and trolls and creatures who are not to be found in the real world.

For Villa Lante’s astounding Water Chain, Cardinal Gambara’s architects bowed to natural forms, as they modeled stone carvings upon the leg joints of a 30 million-year-old sea creature. The Water Chain presents a perfect synthesis of organic forms and human technology, and suggests that, at least in this part of the garden, a

truce had been called by man in his struggle to dominate Gaia.

But, during Cardinal Gambara’s tenure, quite of bit of water-mischief was also at play, as joke-fountains drenched unsuspecting passers-by. And the stone claws of an enormous Crayfish curl over the balustrade above the Fountain of the Giants. This is a garden that exalts reason and order, but Villa Lante is also a place with gentle wonders that fill a visitor with the emotions of surprise and happiness.

In the design of his Sacred Grove in Bomarzo, Vicino Orsini made few geometrical efforts to impose order upon the garden that he’d chosen to locate in a nearly-invisible fold of the Earth. Except for laying out two Squares (the Piazzale of the Vases, and the Piazzale of the Pine Cones), Vicino was content to allow the character of the land to determine the course of his garden paths. This was an utterly UN-Renaissance-like approach to garden-making, because, by leaving the Land intact, the Duke was conceding that Nature was not in need of taming. Many of the statues that he commissioned were carved from living rock. And so, although the multitude of ragged tufa boulders which had always jutted out from the ground were refashioned into images which reflected Vicino’s myriad preoccupations — about sex and poetry and warfare and myth and politics and fear and mortality — the statues are still essentially of the Earth. The carved figures’ random locations and imposing scales remind us that, despite the artistic alterations that Vicino made — which imposed his human voice upon lumps of porous limestone — each of those statues comes from natural Rock, and so continues to rest on the spot where it, as a Rock, has always been.

An amateur psychologist might conclude that, when designing his garden, Orsini gave free reign to his Id. Within his woodland, Orsini created a refuge where disorganization was acceptable… where his Protean nature could express itself, without regard to the fashions of the time or the demands of reality. Each time Vicino climbed back up the hill to his Castle, he had to reassume the responsibilities of being the Duke of Orsino. But when he wandered back down into his Boschetto, he was temporarily the King…not of Nature, but of a world that reflected his deepest thoughts and instincts. Vicino etched volumes of riddles and maxims into the rock of his garden. Upon an obelisk is this, his simplest, and most telling message: “Just to Set the Heart Free.”

Copyright 2015. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

7 Responses to Two Mannerist Gardens in Northern Lazio, Italy