APRIL, 2015

As we create our gardens, we often find that the presence of plant material alone cannot satisfy our aesthetic sensibilities, and so we begin the often perplexing quest for objects to use as decoration for our little Edens. Sometimes, our beds of well-tended plants seem incomplete and in need of punctuation. The dedicated gardener then seeks art…objects with which to literally gild the lilies that she grows.

Whether or not we’re aware of it, our collective notions about what the roles of sculptural adornments in gardens should be harken back to concepts that were reborn during the Italian Renaissance.

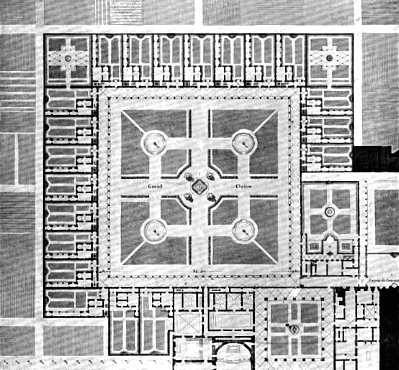

For 1000 years prior to the late 1400s, formal gardens in Europe had been primarily utilitarian places where food, roses, and medicinal herbs were grown. Certainly, in the Medieval cloister garden, some thought was also given to creating a beautiful and peaceful ambience, but apart from decoration applied to central well-heads, those spaces were largely unembellished. A Medieval garden was, above all, a place to bow down to the greater glory of God and his Creations. The uniformity of such gardens—which were all laid out on a square, with paths that crossed at a central point to honor Christ’s death—was a given.

During the Italian Renaissance, the rise of Humanism encouraged rulers and the intelligentsia to consider that, while they could continue to live as Christians who piously humbled themselves before God, they could also begin to joyously cultivate all of the temporal pleasures which were due to humankind, and, particularly, to themselves. In this new environment of thought, society’s dominant castes recognized that, much as the ancient Romans had once done, the most effective way for the powerful to demonstrate their might would be to create rituals, and spectacles, and palaces that were expressly meant to capture the public eye. Italy’s ruling families utilized every aspect of their lives, both public and private, to symbolically announce their might and influence. They built themselves grand villas, and around them they planted the first extravagant gardens that had been fashioned, since the glory days of the Roman Empire.

Using a stock repertoire of mythical symbols and allegories resurrected from Roman antiquity, the nobility made gardens that, apart from providing their households with food and flowers, performed two essential tasks. Task one was to symbolically demonstrate man’s control over the natural world; and this was accomplished through geometry, as garden beds were planted to conform to precisely-ruled shapes. Task two was to introduce concepts and themes into the minds of those who visited the nobles’ gardens: this was achieved by using sculptures as the vehicles by which those ideas would be delivered. Strategically-chosen statues were mounted with serious intention. Each statue was meant to attest to the virtues and aspirations of the garden-makers themselves.

In the Renaissance, the widely-understood iconography of ancient myth enabled statuary to function as message-bearer. If a nobleman wished to proclaim that his strength rivaled that of Hercules, or his wisdom equaled that of Athena, no words were needed. Instead, statues referring to classical mythology were mounted prominently in the nobleman’s garden. With sculpture, ideas were silently but clearly stated. “As is the gardener, so is the garden.” This notion became central to garden design. No longer was a garden made in deference to a Medieval God. Instead, a garden became a paradise which mirrored the magnificence of its human creator, and its decorations were used as the embodiment of ideas, and for the definition of self.

While I’d love to give you a comprehensive look at how the use of sculpture in the gardens of the Western World has developed over the past 500 years, practicality requires that I begin in a recent era, and so the in-depth portion of our photo tour will start at the beginning of the 20th century … when sea-changes in the established patterns of living were underway and when no aspect of life would go untransformed. In 1900, European monarchies and Imperial Powers still dominated. But global conflict, along with technological, scientific, and medical advances, would soon turn the world on its collective ear. Small wonder that, even in the realm of garden design, traditional styles of decoration began to give way to abstract or idiosyncratic pieces of art. And now, in the early decades of the 21st century, garden art has come to symbolize entirely new sets of concepts; concepts which would have been meaningless to the Ancients.

We’ll see how, in the early 20th century, conventions in English and American garden décor began to break free from the historical models which had persisted in the Western World since the early 1500s, when the Medici had established the paradigms for garden decoration. We’ll visit a handful of English homes where contemporary sculpture has been used to usher antique gardens into the 21st century. We’ll also see how recently-made pieces have enlivened a variety of gardens …gardens which range from the humble to the grand.

Each of these gardens that I’ve chosen to illustrate would be certainly LESS, if deprived of their various, sculptural additions. Every picture you’ll see here will be of a place that I’ve actually visited…this is because I’m unable to properly understand garden art unless I’ve walked ‘round it, in its actual setting. I hope this whirlwind tour will stimulate your imaginations, help you to refocus your vision, and inspire you to consider making modest sculptural additions to your own gardens.

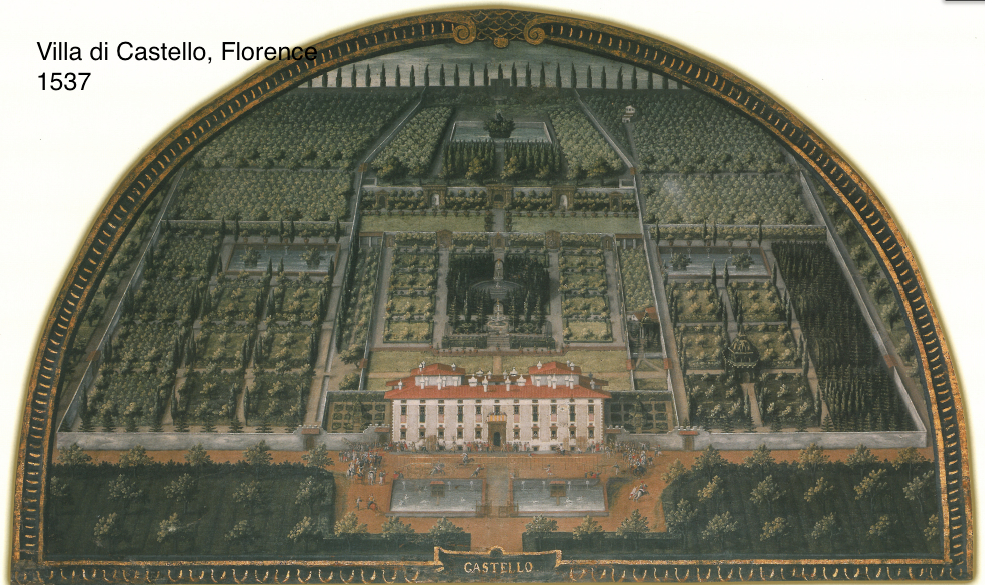

Even though we’re avoiding full immersion in garden design history, as a jumping-off point, we must briefly acknowledge the garden at Villa di Castello, on the outskirts of Florence, which was designed in 1537.

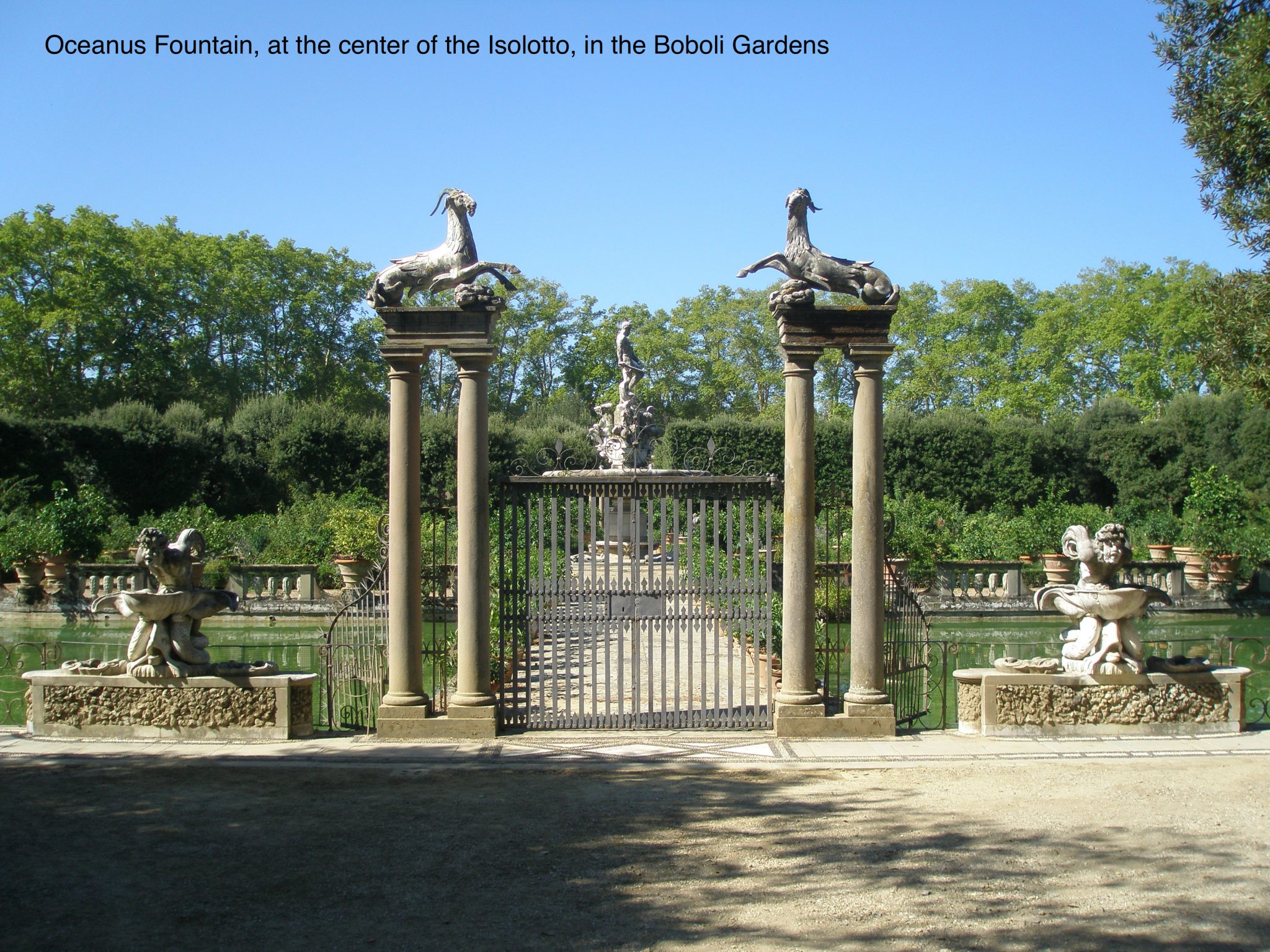

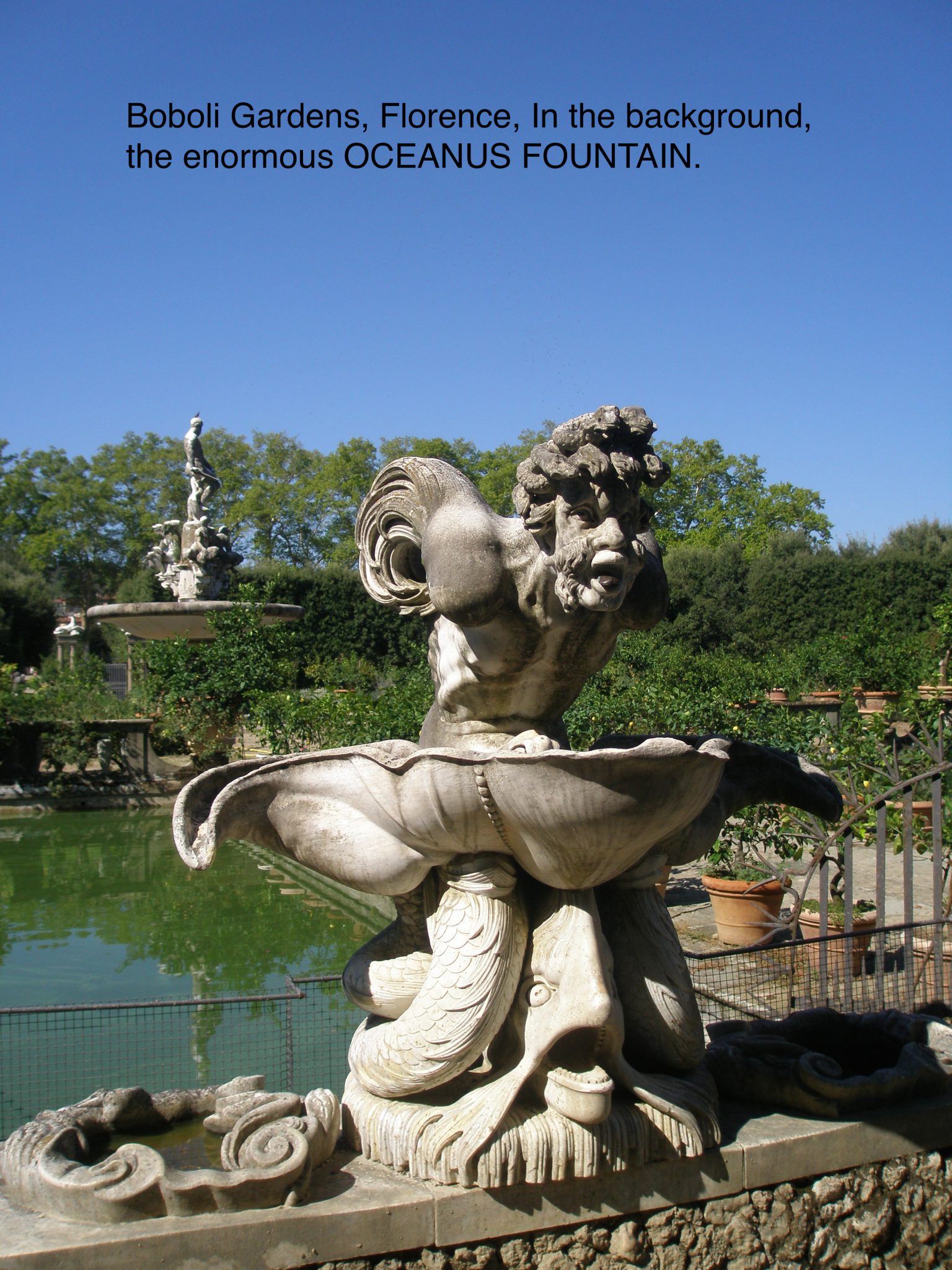

This estate established a standard for the use of garden sculpture which then persisted through many centuries. Castello is the first real example in Renaissance Italy of a garden created to celebrate the glory and influence of its owner: Cosimo de Medici, the 1st Grand Duke of Tuscany. In this garden, as well as at the nearby Boboli Gardens, (which were part of yet another of the great, Medici residences), statuary was a dual-purpose tool: arrayed as much to entice the eye as it was deployed to tickle the mind.

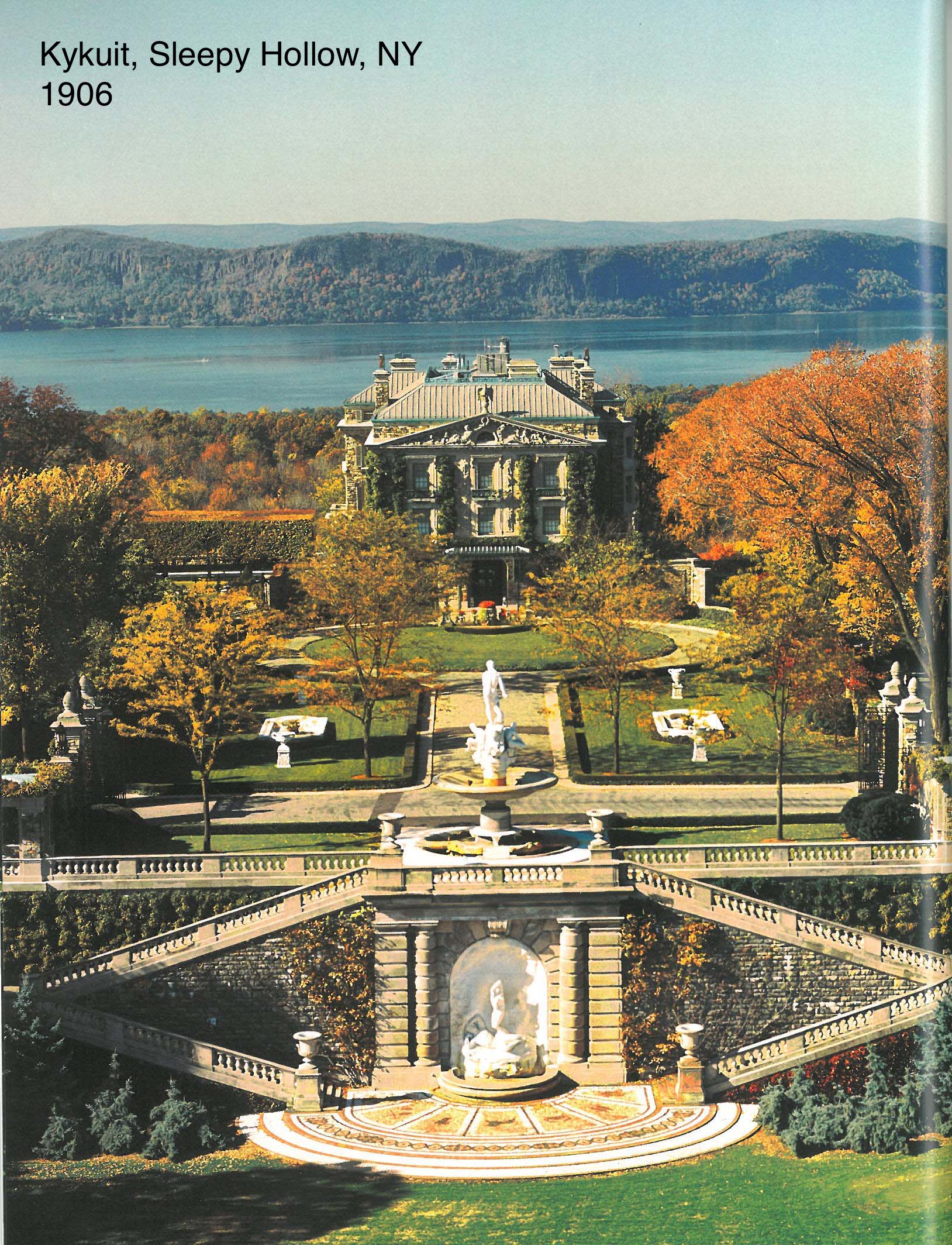

We’ll travel forward now, across 4000 miles and 350 years, from Renaissance Italy to Sleepy Hollow, New York…to arrive at a garden begun at the zenith of America’s Country Place Era.

And what had changed, at least when it came to the gardens of the Western world’s wealthiest and most powerful? Very little, it seems. Just as the Medici had erected a fountain by which they claimed kinship with the god Oceanus—who ruled the seas, and from whom all rivers sprang—in 1914, at Kykuit, John D. Rockefeller commissioned his very own Oceanus fountain…

My rainy-day-in-June view of Kykuit’s Oceanus Fountain, as seen from the front portico of the Main House.

… by which he suggested HIS similarities to past rulers, both human and mythical.

As I look at the Kykuit Oceanus, what I mostly see is an unimaginative and bombastic imposition upon the Hudson Valley landscape. For Rockefeller, the principal of GENIUS LOCI — the idea that garden designs should always be adapted to the contexts in which they’re located — was clearly not an operational concern.

And in his Rose Garden, Rockefeller placed this much more charming but still referential decoration…another copy of a Boboli Garden fountain.

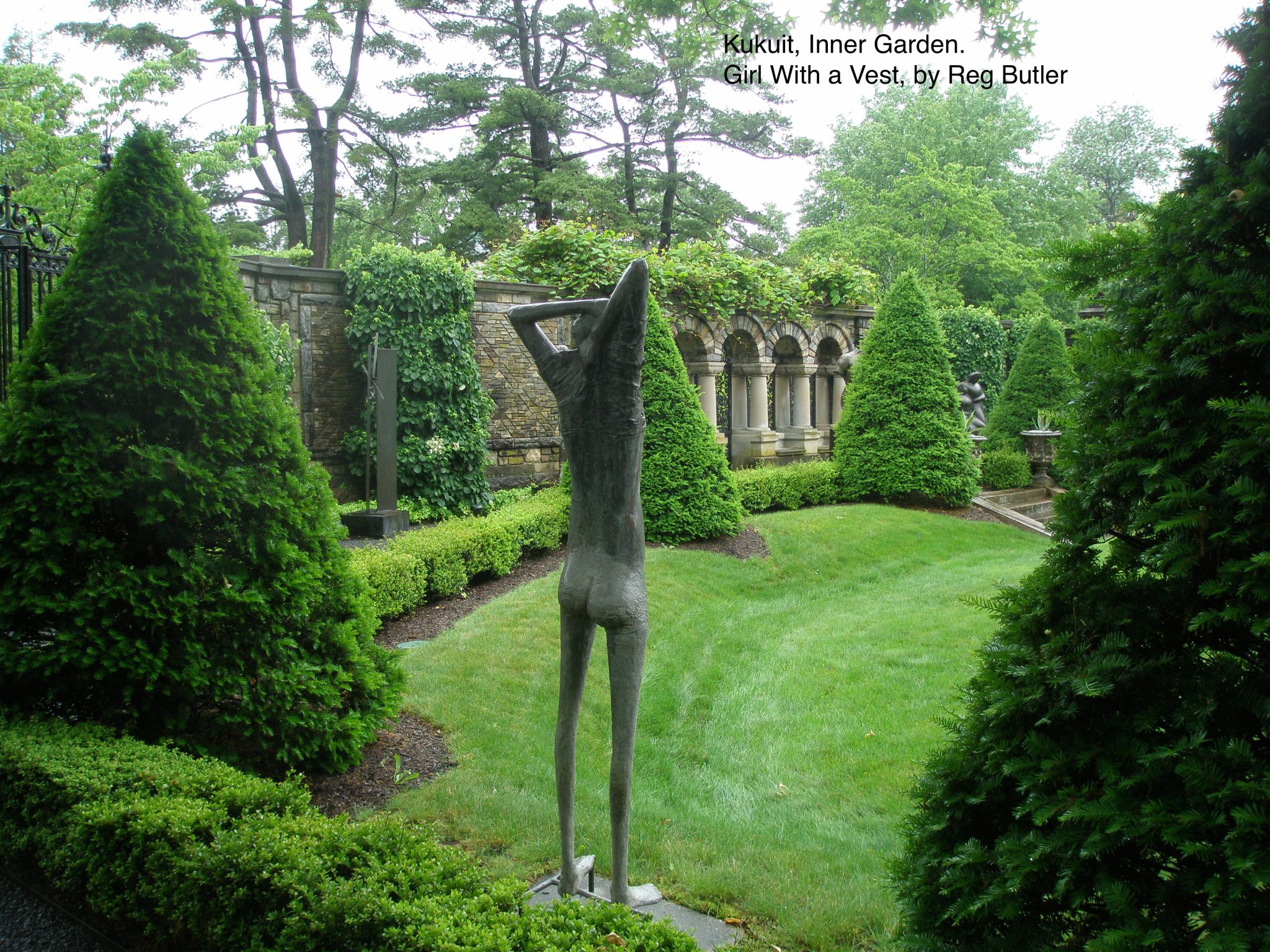

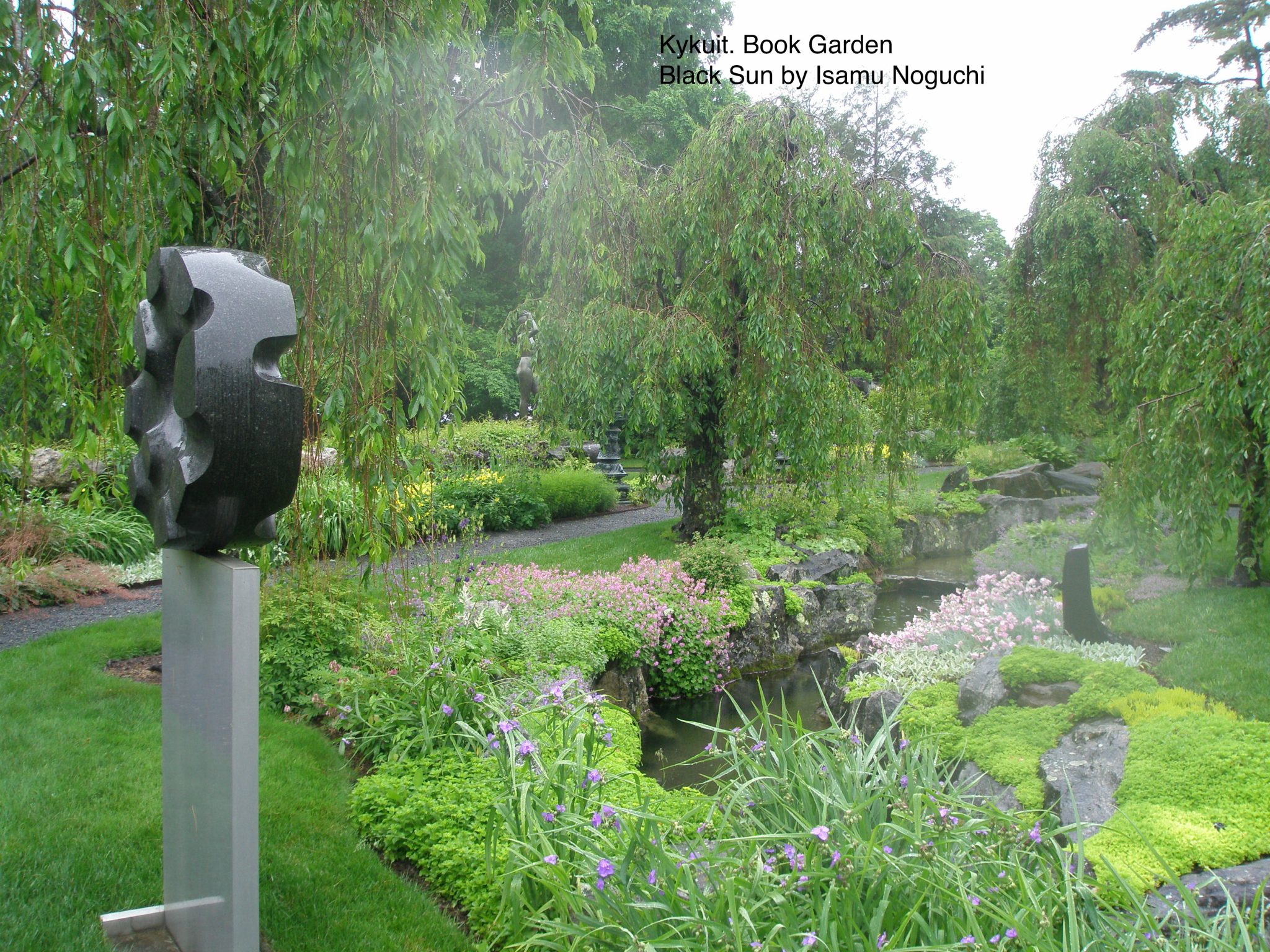

But eventually, when John D. Rockefeller’s grandson Nelson turned his youthful energies to decorating the terraces and meadows around the family home, Kykuit’s art began to reflect the modern world, and so became America’s first, and most significant private garden to be adorned with contemporary sculpture. From 1935 until his death in 1979, Nelson Rockefeller’s tastes evolved, and he acquired sculpture in a wide range of styles. We who today visit Kykuit can never hope to acquire equivalent pieces for our own gardens. However, Kykuit’s opulent grounds are relevant to even the most humble gardener for a single, powerful reason: Nelson’s careful siting of each piece of sculpture provides us with a master class in how to sensitively integrate art into a garden.

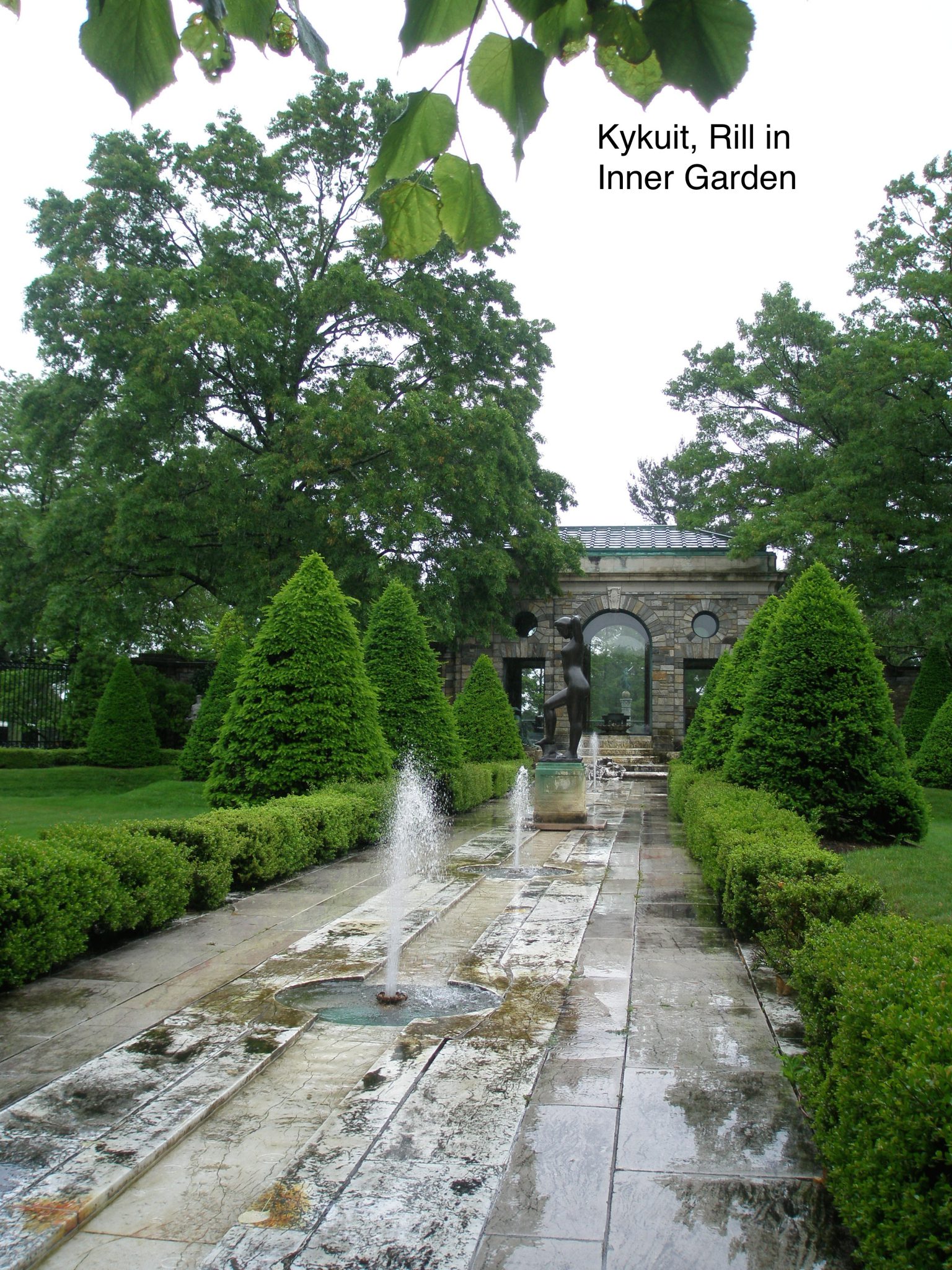

Here now, a tour of Kykuit’s gardens:

A collection of bronzes: lined up along the wall of the Inner Garden….rather too crowded for comfort.

Sculpture from 1953 in the Inner Garden. This piece is mounted with breathing room around it, and the effect is splendid.

And in 1966, the most artfully-sited piece of all was placed below the Maple Walk. I took this picture in early June of 2013, during a violent rainstorm, and the silhouettes of the wet tree trunks combined with the Calder sculpture were wonderful.

We’ll leave America now, and cross the Atlantic to look at a modest English garden that was begun by an artists’ collective during the same period as when John D. Rockefeller was imitating Florentine nobility on the grounds of his New York estate.

Charleston, East Sussex, England. A small pool at the center of the Walled Garden’s lawn is edged with tiles that are reproductions of the original tiles, which were painted by Vanessa Bell in 1930.

In 1916, the artist Vanessa Bell, with her two young sons by her husband Clive Bell, along with Vanessa’s sometime-lover Duncan Grant, as well as Duncan’s sometime-lover David Garnett, set up house in a rambling, former inn, that was nestled in a boggy valley, below the South Downs of East Sussex.

After this group settled, they were often joined by Vanessa’s estranged husband Clive, who was given his own bedroom there, and by another of Vanessa’s former flames, the art critic Roger Fry, who was also the founder of the Omega Workshop. Somehow, living in this hothouse of shifting emotional alliances stimulated the ideas and talents of these people—who were all accomplished painters and sculptors—and together they generated an enormous output of art….a bit of which found its way into the gardens outside the house, which they had named Charleston.

In 1919 Vanessa’s sister, the writer Virginia Woolf, moved to Monk’s House, a farmhouse that was part of an abandoned pig farm, in a nearby village.

[Note: in a future Armchair Traveler’s Diary, I’ll show you much more of Monk’s House—inside and out–along with the interiors at Charleston.]

The sisters came from the Stephen family— a highly-cultured, and overwhelmingly traditional London clan—and both women felt suffocated by the curtailed options which society offered to ladies of their class. Both sisters married young, as they were expected to do, but thereafter each began to live according to her own terms. The sisters’ rejections of their respectable upbringing had the inevitable consequence of intermittent poverty, but with ingenuity, and incessant labor , Vanessa—with her various colleagues—and Virginia—with her husband Leonard, who was the most talented plantsman of the bunch— made lovely little gardens, which reflected departures from the elaborate and stiff style that had been the norm, during their Edwardian childhoods.

We’re going to visit Vanessa Bell’s Charleston now, which is to this day still at the center of a working dairy farm.

Charleston’s Cows, last May, when Anne and David Guy and I visited Vanessa Bell’s home in East Sussex.

As during Vanessa’s time, the bracing odor of manure fills the air. When Vanessa began gardening, her first concern was to provide food for her children. She grew fruit and vegetables, kept rabbits, chickens, a pig, and bees. But Vanessa’s bone-deep need to enhance her environments soon extended outside the house, which she’d already embellished with patterns and color.

Charleston’s gardens are small and planted in painterly swathes of color. The specific identities of the artists who produced the sculptures and decorative brick that adorn Charleston’s gardens are sometimes unknowable because the members of the Omega Workshop produced their art anonymously. Most of the identifiable work was added by Quentin Bell, the son of Vanessa and Clive. But, regardless of origin, the sculptural elements in Charleston’s gardens, which were made over many decades, from 1916 until 1973, all exhibit humor, and a rustic, hand-crafted power. I’d be happy to include any of these features in MY garden.

Two Urns, made in 1956 by Quentin Bell, mark the entry to Charleston’s front courtyard. The on-site shop sells reproductions of these, but they’re enormously heavy. And so, although I longed to acquire an Urn, I didn’t have one shipped back to my garden, in New Hampshire.

And Quentin Bell’s statue of POMONA, also made in 1954, guards a path to the Orchard. Pomona is a Roman goddess, and the keeper of fruit trees.

A Bust is mounted, just inside the entry to the Walled Garden. This wall is built with typical Southeastern England’s combination of brick and broken flint stones.

A section of the Walled Garden. Duncan Grant and Vanessa Bell chose all of the plants for the garden, and today’s beds have been filled with those same flowers. Along the top of the brick wall in the background are the numerous busts of Ancient Greeks, which Duncan lifted from art schools.

The Lady is tucked into the Drunken Hedge, which extends across the width of the Walled Garden. Drunken Hedges are in themselves a form of living sculpture. ( In a future Diary I’ll show you more examples of Drunken Hedges. )

When I compare the sleek gardens at Kykuit with those made by Vanessa Bell and her elastic household, the appeal of owning trophy art lessens. I compare the Rockefellers’ insatiable collecting of name-brand artists with the Charleston occupants’ production of decorative pieces and I realize that Charleston’s greatest gift is the example set by its home-made garden ornaments, all of which suggest that anyone of us with imagination and time to spare could at least make a stab at devising some sculptural pieces of our own.

But remember, even the free-thinkers at Charleston saw fit to add a garden deity—Pomona—the goddess who protected their orchard. A garden…whether ancient or modern…often seems to want a symbol of its guardian spirit.

Which brings me to the inevitable issue of Garden Gnomes.

In the 19th century, in Germany, garden gnomes began to appear in great numbers. Having a gnome in one’s garden was considered prudent: the presence of a gnome was thought to bring good fortune. But, if we look harder at gnome-history, we see that, once again, we can blame the Italians, who, during the Mannerist era—in the mid 1500s—began to place statues of dwarves and hunchbacks in their gardens. Scholars have speculated that these Italian dwarves were versions of the Greco-Roman fertility god Priapus, whose statue was often found in ancient gardens. And so, although the Chelsea Flower Show has banned garden gnomes from their exhibit grounds for 100 out of the past 101 years, I’ve come to the conclusion that the Royal Horticultural Society is being arbitrary and capricious when they say that gnomes detract from a garden’s design. As someone who has been both a Chelsea exhibitor and a spectator I’m lodging a tiny protest, and so this Spring I’ve just placed a single gnome into a corner of my shady, Hosta bed.

I already have an antique bust of the messenger god mounted in my garden….and it’s about time for my Hermes to have a little fertility god nearby, just to keep things from getting too serious.

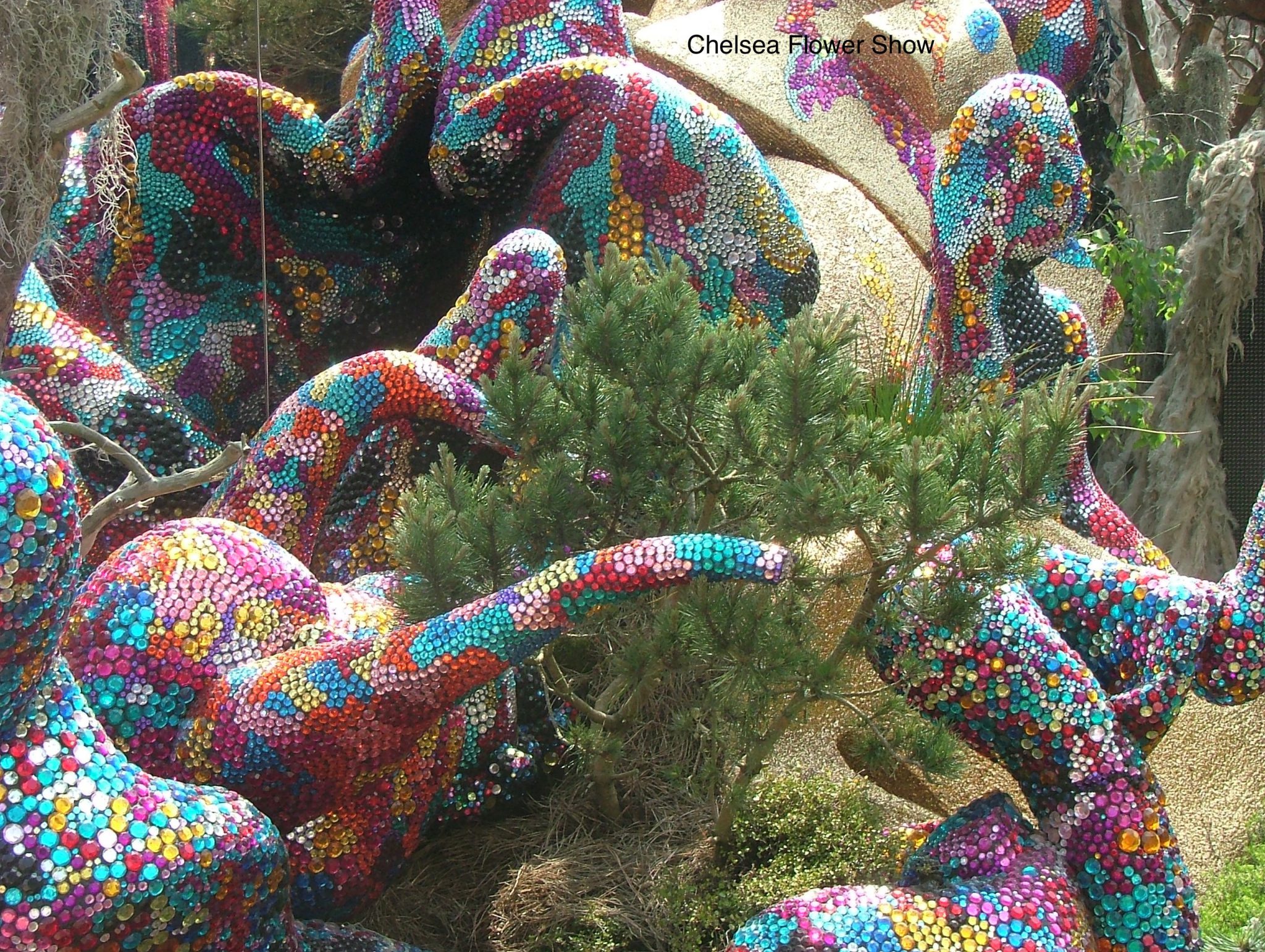

Now, since the Chelsea Flower Show has entered the conversation, here’s a selection of garden sculpture exhibits, from the past several Shows. Some of these pieces are obviously, massively expensive, while others are not. But every display offers food for thought.

This final, Chelsea image is the most intriguing. It consists of nothing more than painted lengths of rough wood that are stuck into the ground. If you’re looking for a template for an interesting do-it-yourself garden decoration project, this might be it.

Among historians of late 20th century garden design, the next garden that I’ll show you is the most famous do-it-yourself project of them all, as well as the most controversial.

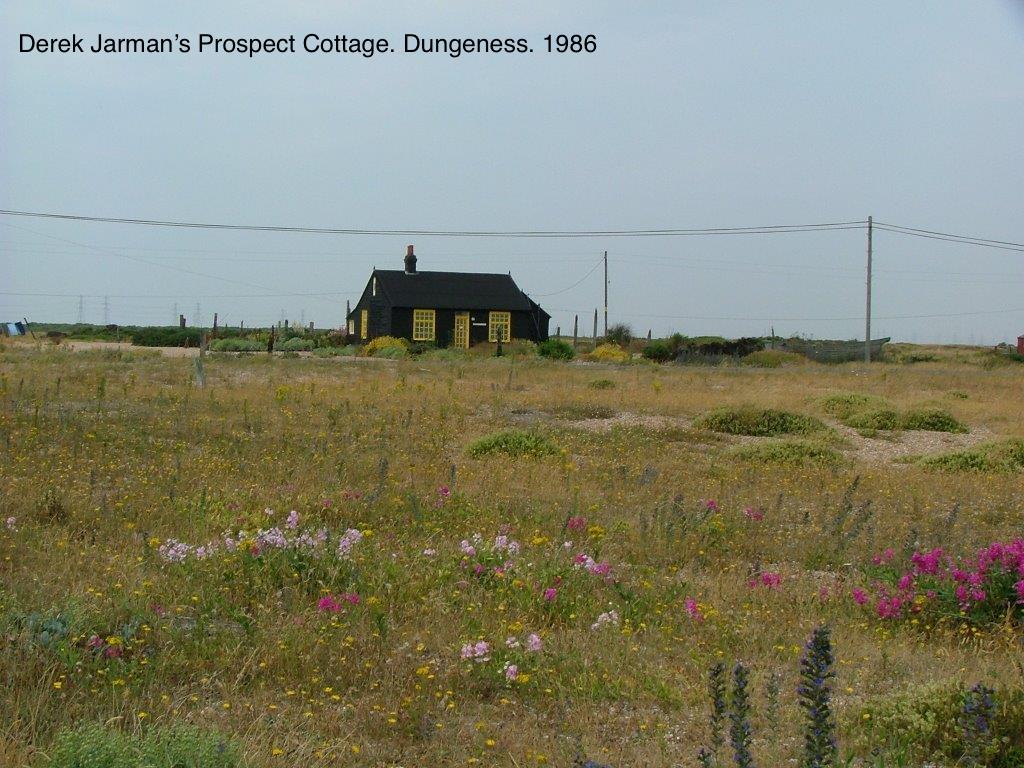

The View of Prospect Cottage, from the shingle beach. All of the photos you next see of Derek Jarman’s gardens at Prospect Cottage were taken by the English garden designer Anne Guy.

In 1986, as he was dying of AIDS, the British film director Derek Jarman retreated to a cottage in Dungeness, on England’s southern coast. When I went there in August of 2013, it seemed as if I’d left England behind. With one of the largest expanses of shingle in Europe, the Dungeness peninsula is classified as Britain’s only desert, and the military has long used the beach and marshes for training exercises. And within sight of Jarman’s house, which he named Prospect Cottage, the gray towers of the Dungeness Nuclear Power Station loom.

Telephoto view of the Nuclear Power Station at Dungeness, as seen from the gardens at Prospect Cottage.

But, despite the apparent bleakness there by the English Channel, Dungeness is actually full of life. Multitudes of birds and insects flourish, along with more than 600 types of native plants; the entire area is designated a Nature Reserve.

Jarman’s daily walks along the rocky beach yielded materials that appealed to his artist’s eye. Piles of polished stone, bundles of bleached driftwood, and twisted lengths of rebar began to accumulate outside his front door. Almost without thought, Jarman began to arrange his stones in patterns on the ground…

… and to stake newly-planted beach roses with the driftwood…

…and to barricade tender plants behind curlicues of rusted metal.

When all was said and done, Jarman had created a post-modern and highly context-sensitive garden, one which was a complete rejection of what he saw as the sterility of modernism. He loved allusion and stories…

… and had the words of his favorite poem by John Donne affixed to the side of his house. Many cannot appreciate the artistry of Jarman’s garden at Prospect Cottage; I’ve had people tell me his sculptures are nothing but piles of junk. Jarman’s garden looks like it’s on another planet, instead of near Kent, which is known as the Garden of England. But Jarman made a garden that honored the genius of a very particular location, and that integrity is what gives the place its magic.

As I’ve made my annual journeys to England, I’ve discovered dozens of gardens that use contemporary sculpture to distinguish themselves. In just these past two summers, I’ve added the following 5 gardens to my Favorites List. At each estate, recently-made pieces of art blend gracefully with superb demonstrations of horticulture. I’ll show you the gardens chronologically….organized by the date when the House on each property was built. And remember, even though all of these gardens are open to the public… some on a very limited basis…these places, though magnificent, still have a primary function as HOMES, where gardens are influenced by the tastes and personalities of the homeowners.

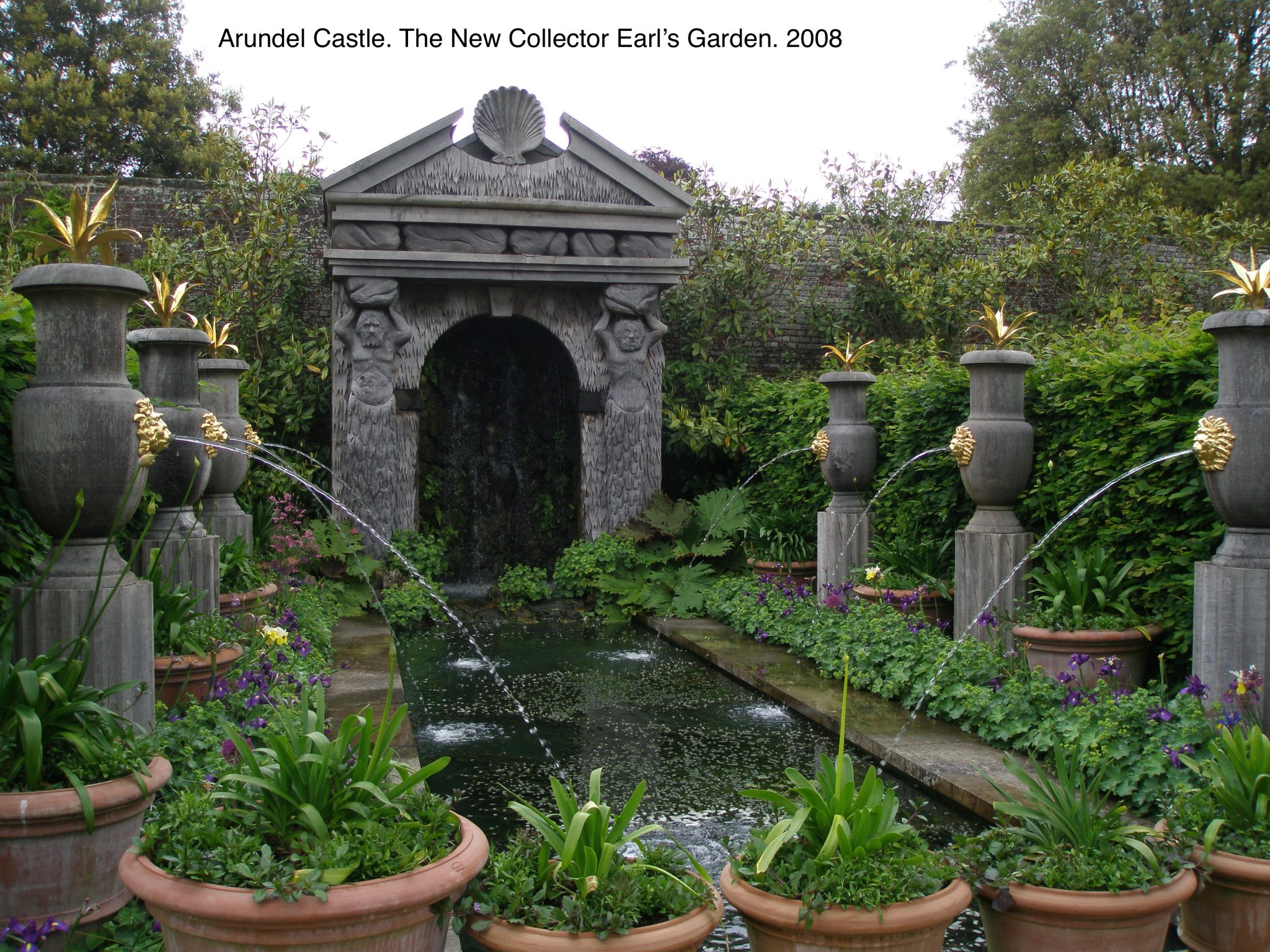

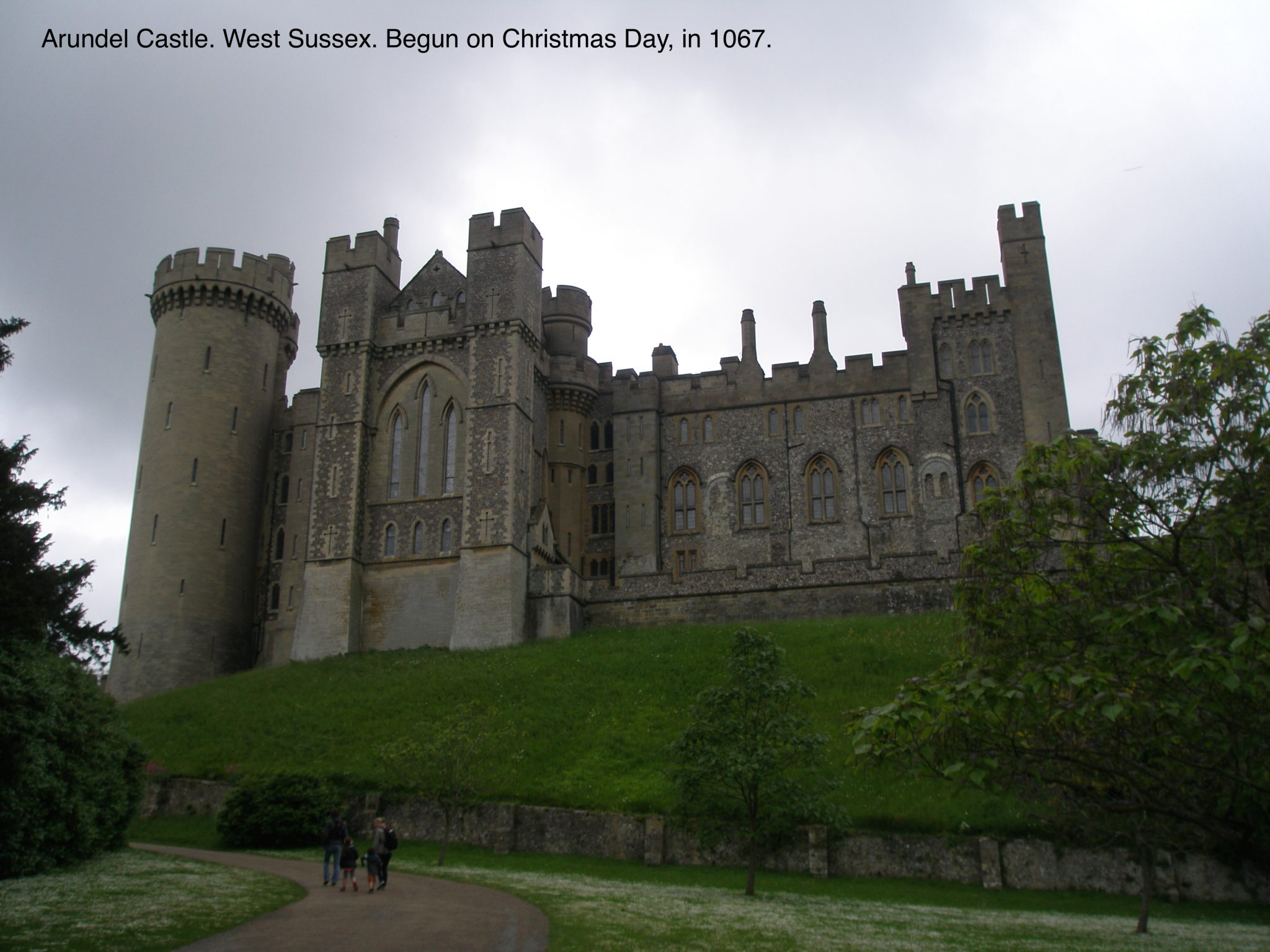

First, to Arundel Castle, in West Sussex.

The Castle was begun on Christmas Day, in 1067.

Thirty acres of gardens and parkland surround the Castle, but what most interested me was the Collector Earl’s Garden, which was opened in 2008.

We owe the existence of this garden to the current Duchess of Norfolk, Georgina Fitzalan-Howard, who named the garden in honor of her husband Henry, the Earl of Arundel and Duke of Norfolk.

All of the sections of the New Collector Earl’s Garden were designed by Isabel and Julian Bannerman. The Bannermans’ gardens include ornamental features inspired by the classical garden vocabulary, which are modernized by carvings made of green oak, used in place of stone. When the green oak ages, the wood becomes as unbreakable as rock.

Here we have a fabulous example of a Borrowed View! Although the Cathedral isn’t part of the Castle grounds, the New Garden cleverly uses the forms of the Cathedral as a backdrop for the forms in the Garden, which echo the Cathedral’s spires and windows.

But what really got my attention was the huge expanse of the STUMPERY, where massive tree roots are upended and used as visual anchors for wild and wooly garden beds. These towering plants are commonly called Tree Echium, or Pride of Madiera, and are native to the Canary Islands.

Just to drive home to you the enormity of Tree Echium, which are used for sculptural effect, here I am, to provide human scale.

A final look at the Stumpery…and see how the blossoms of the Lupine mimic the shapes and tracery of the Cathedral windows! This is gardening, being practiced at the highest levels.

So, this oldest Home of our tour, which happens to have the newest garden, forced me to reassess my hatred for the uprooted tree stumps in my own yard. Next summer, instead of automatically chipping them, I’ll be evaluating each stump for its potential as garden sculpture.

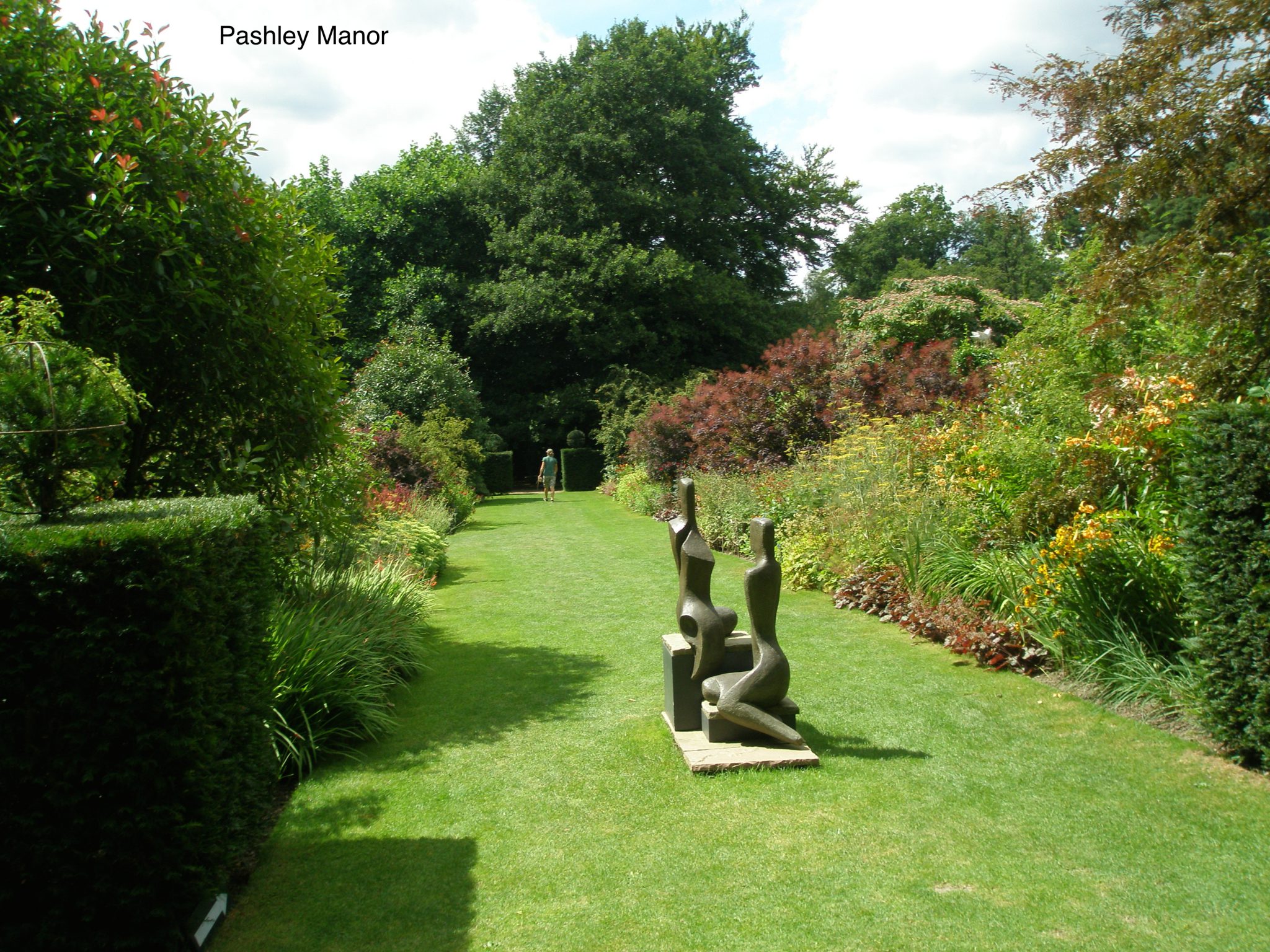

Next, to Pashley Manor, in East Sussex.

This house was built in 1550. But earlier, the site had a hunting lodge that was owned by the family of Anne Boleyn. The gardens at Pashley were established in 1981, and in year 2000 were voted the best Garden in the United Kingdom, by the Historic Houses Association. The sculptural additions here are romantic and largely narrative, and reinforce the fairy-tale atmosphere of the East Sussex hills and sheep-filled meadows.

Sculpture on a grass path welcomes us. (Note: Pashley Manor is another of the many gardens that Blue Badge Guide Amanda Hutchinson and Chariot-Driver Steve Parry have taken me to. And in July of 2015, Amanda and Steve and I will resume our touring; this time concentrating upon Surrey, and East Sussex…and with a bit more of Kent, thrown in for good measure).

Amanda’s contact info can be found in the Borde Hill section of this Diary.)

At the edge of the Ha-Ha that separates the gardens from sheep meadows, this 8 foot tall lady exposes her shapely leg.

I waited for the clouds to pass, and was rewarded with this lovely shadow…which brings up the point that the shadows cast by garden ornaments can be as important as the objects themselves.

The island has a temple, and a statue of Pashley Manor’s most unfortunate visitor. The Boleyn family’s hunting lodge once stood on this island.

We continue, to Borde Hill, in West Sussex, which is yet another of the exquisite English gardens that Blue Badge Guide Amanda Hutchinson has led me to.

Amanda’s contact info: www.southeasttourguides.co.uk

The House was built in 1598. An Arboretum was planted in 1893, and 17 acres of formal gardens began to be established in 1965. Borde Hill is famous throughout England for its Rose Garden, and was recently named by the Historic Houses Association as English Garden of the Year. The collection of sculpture is eclectic, but each

piece is perfectly chosen to complement the lush plantings …. once again, a reminder that, regardless of sculptural style, careful siting of garden art is everything.

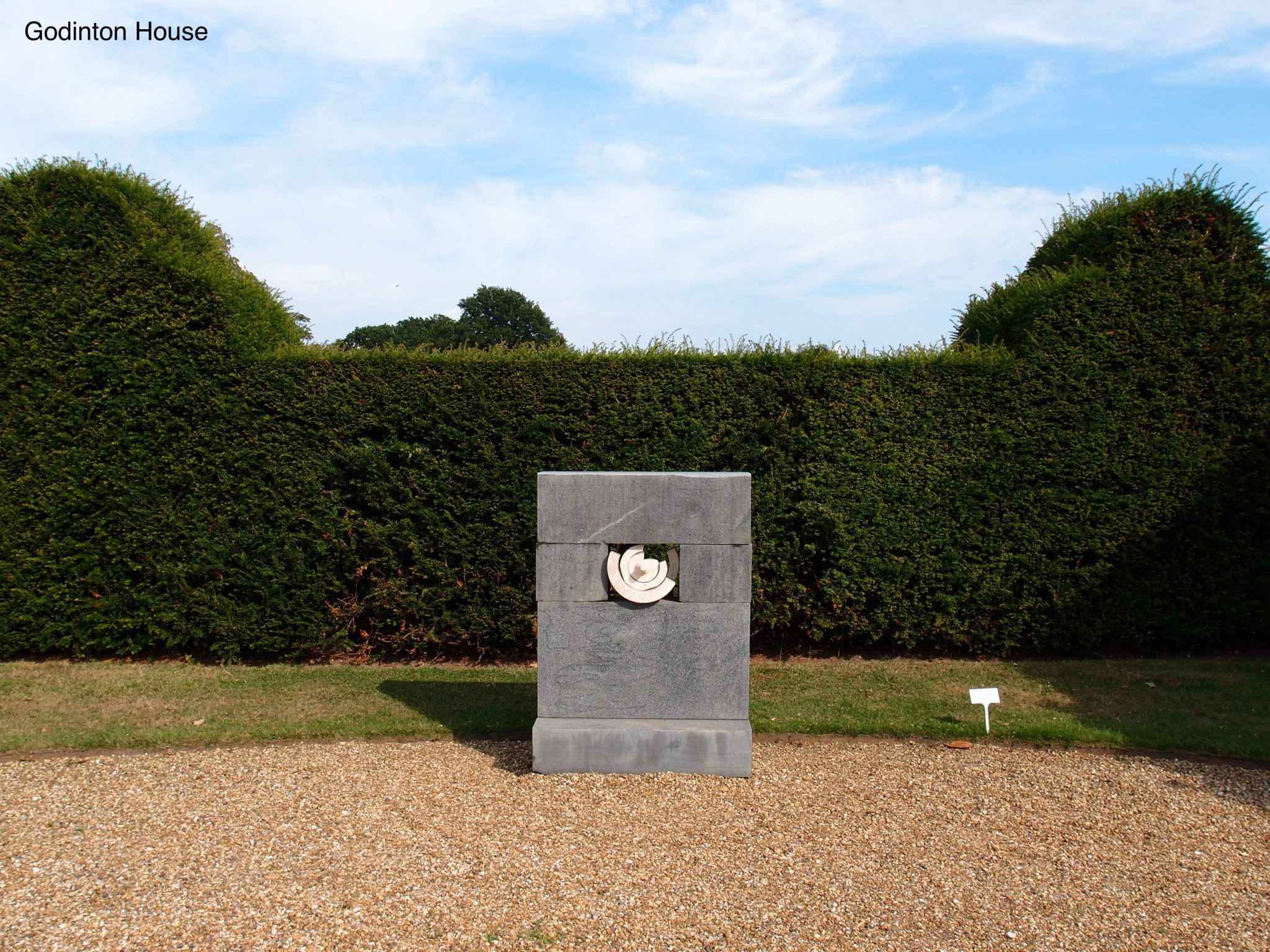

Onward, to Godinton House, in Kent (to which Amanda and Steve and I traveled in August of 2013).

The house was remodeled in 1628, when a Jacobean exterior was added. During that renovation, which enclosed a medieval structure, Roman bricks were found in the building’s foundation. The gardens we see today were begun in 1879. Traditional and contemporary pieces of art are widely-spaced, and coexist nicely in the tranquil, parkland setting.

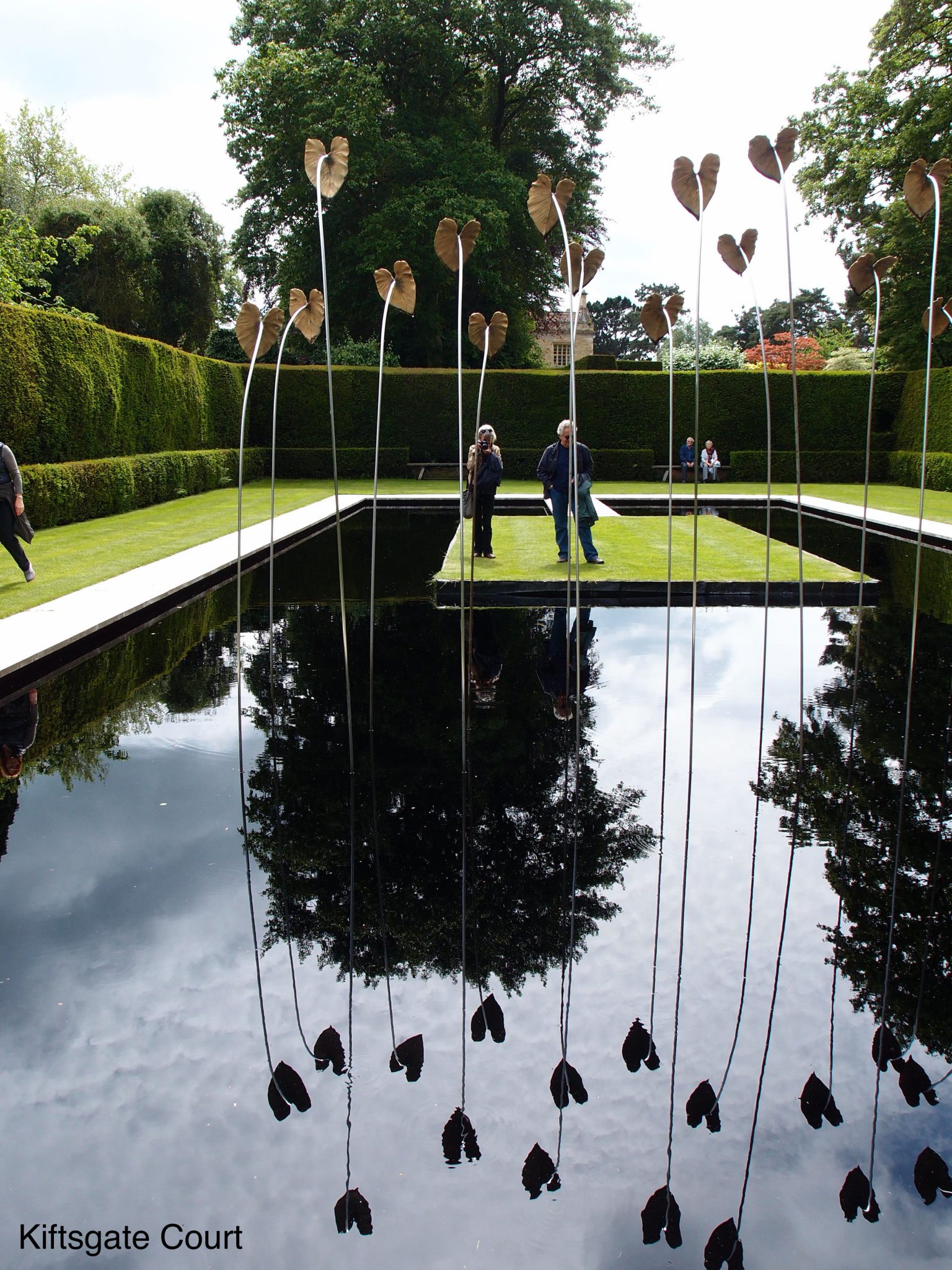

Continuing, to Kiftsgate Court, in Gloucestershire.

On June 7, 2014, I traveled to Kiftsgate Court with

Anne and David Guy,

Janet Hardwick, and Barry West. ‘Twas an Excellent Outing: good company, tasty food (in the Kiftsgate Cafe), and a jaw-droppingly beautiful garden to discover. This is a garden to revisit, time and time again.

These gardens are directly across the road from the World-Famous gardens of Hidcote, but, strangely, Kiftsgate remains little known. The House was built in 1887, and gardens have been continually added, since 1918. The water features at Kiftsgate, which are essentially sculptural, direct one’s views–both close and distant–and anchor one of the most beautiful little gardens you’ll ever see.

WOW !!!! At the edge of the Terrace, this view reveals itself. I’m looking down toward the swimming pool, which was installed in 1960. In the distance are the Malvern Hills. Wales is on the far side of those Hills.

No photo can describe the surprise I felt, when this vista unfolded below me.

Part-way down the steep path which leads to the pool, in a grove of Scotch Firs, is this stone carving called MOTHER AND CHILD, which was added during the 1980s.

View from the Half-Crescent Pool, up to the Summerhouse, and then to the Main House. The Gardeners who maintain the plantings on this steep slope must wear safety cables when they’re working.

The Sunken Garden, which was built next to the Main House in 1972, is centered upon an ancient fountain that was brought to England from the Pyrenees Mountains.

Near the Yellow Border, an old stone gatepost rescued from a nearby field has become a piece of sculpture.

Another WOW moment, as I passed through an opening in a high, yew hedge and saw this. The Water Garden, added in 1998, replaces an old tennis court. The pool is surrounded by narrow, white paving stones which contrast with the black water. Stepping stones lead to a grassy island.

Sculptor Simon Allison designed 24 stainless steel stems that are topped with gilded bronze leaves molded from a philodendron. The stems sway gently in the wind and reflect well in the dark water. Every 5 minutes, water begins to stream from the tips of the leaves.

Anne and David Guy stand on the Water Garden’s island, to provide human scale. And, in the background, Janet Hardwick and Barry West wait very patiently for me to finish my picture-taking.

Before I take us back to America, to look at two Massachusetts gardens, I’d like to show a charming, little English garden… located in the West Midlands.

In designer Anne Guy’s Worcestershire back yard, natural materials and discarded metal that she and her husband David have gathered during their frequent visits to Lyme Regis on England’s Jurassic Sea Coast have been transformed into sculptures. Elements of classically-styled decoration have been strategically used. And small works by local Glass artisans have been tucked into beds of perennials.

Anne Guy’s contact info: www.anneguygardendesigns.co.uk

One of my Lorenzo Love Seats is placed at the back edge of Anne and David’s garden. Photo courtesy of Anne Guy.

It’s time for us to return to the New World, and specifically to the Berkshires, in Western Massachusetts. I’ve chosen to highlight these final gardens for two reasons.

Firstly: they’re full of excellent art. Secondly: both demonstrate how the use of garden sculpture has evolved, over the past 100 years.

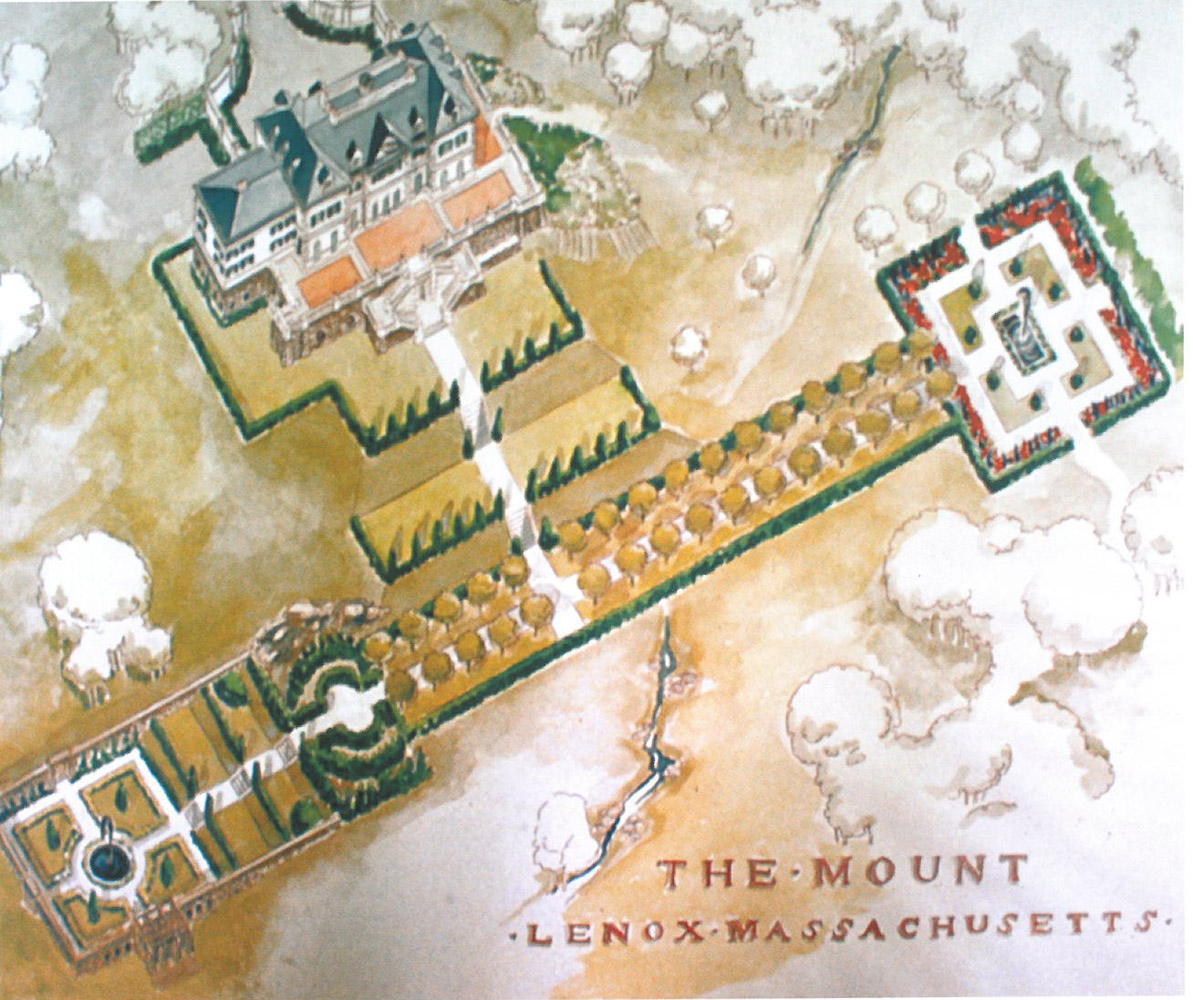

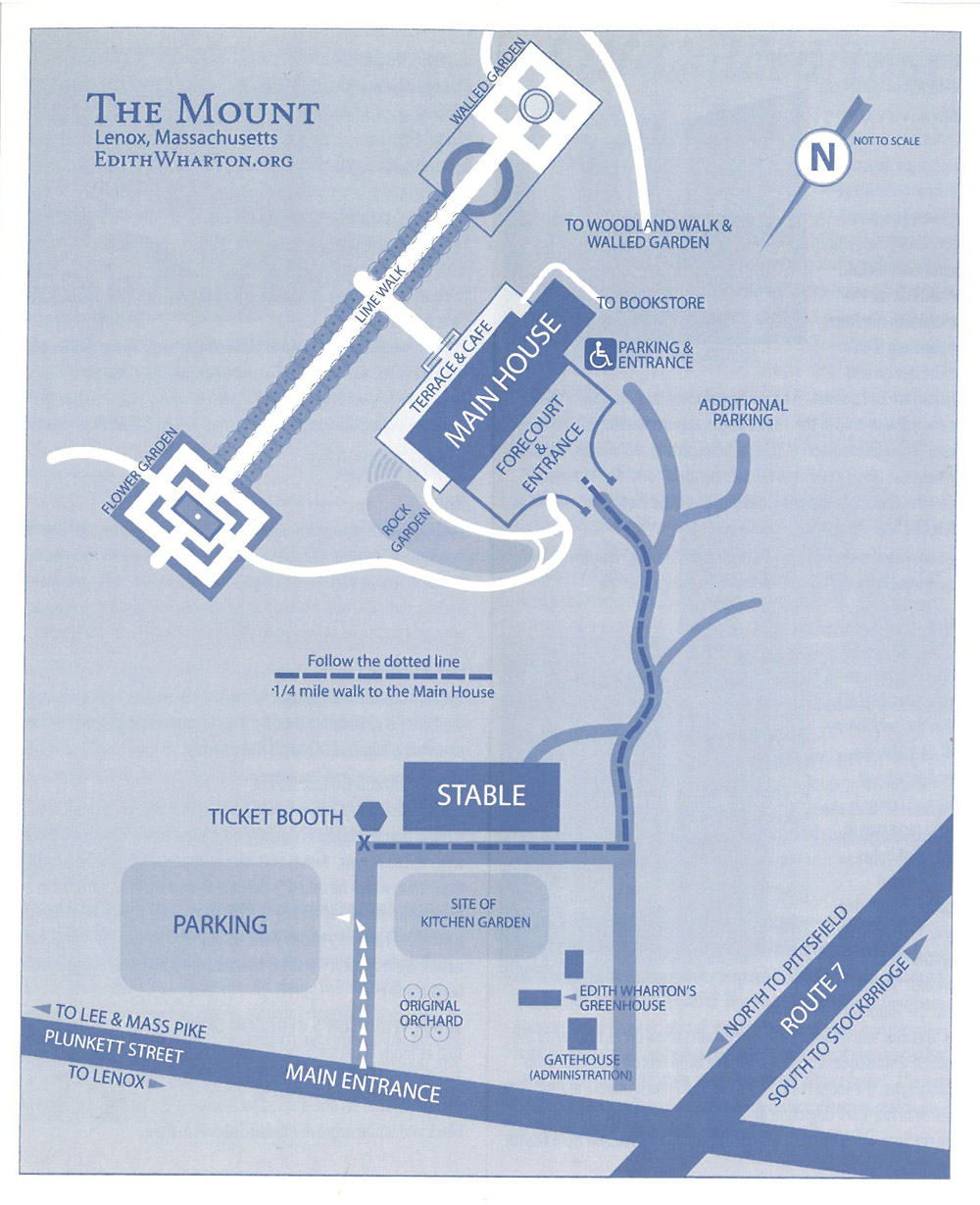

We’ll begin with The Mount…

…in Lenox, Massachusetts, which Edith Wharton built to be what she called her “first real home.” She began at the conclusion of the Gilded Age, in 1901, when she was 40 years old, and for the next 10 years worked tirelessly to perfect every detail. Edith was responsible for the layout of the formal gardens.

She partnered with Ogden Codman Junior on the House Plan. Her niece, the landscape architect Beatrix Farrand, designed the maple-lined front drive, as well as the quarter-mile-long carriage road that winds through a forest, and connects the Stables …

….with the Main House.

Beatrix Farrand also laid out paths through the forest. Once the courses of those paths had been set, Wharton spent considerable time planting woodland gardens, full of ferns and drifts of shade-tolerant ground covers.

But, when staying married to her mentally-ill husband Teddy finally became impossible, Edith had to leave The Mount behind.

She moved to France, where she remained for the rest of her life. For the next 70 years, Wharton’s creation deteriorated, as it was occupied by a constantly-rotating roster of tenants. In 1980, the property was saved from certain ruin, when it was bought by the Edith Wharton Restoration Group, a non-profit organization.

Each summer now, the Trustees at The Mount install a well-curated display of contemporary sculpture in Wharton’s gardens.

The presence of this newly-made work sets just the right tone for a visit to the house, which is once again being used as a setting for the celebration of ALL of the arts, just as it was, when it was Edith’s home.

As I’ve surveyed sculpture in 20th century gardens, I’ve studiously avoided mentioning the phenomenon of America’s Sculpture Parks. These days–and happily—placing large-scaled sculpture in parks, at corporate headquarters, and in botanic gardens, has become a foregone conclusion. But my main interest has always been to see how sculptural art can be integrated into private and domestic settings…settings where the tone is personal, and the scale is smaller.

Here are some of the sculptures I discovered, as I strolled at The Mount. I first circled the Stables, and then continued through the woodland gardens, toward the Main House.

ARCH II, by Ann Jon…with a seat inside. Another masterful exercise of sculptural shadow-play, which can be yours for only $36,000.00 (I confess that I WANT this lovely creation, but…… ) .

MRS.WHARTON. Which shows what can be done with 2 sheets of plywood, a jigsaw, and a quart of paint !!!

This curving path, which connects the carriage drive and the formal flower garden, was laid out by Edith Wharton. It looks utterly contemporary.

Here’s a nice transition, from new to old. In the background: a contemporary, green and white archway. In the foreground: the Flower Garden’s original Trellis Niche (designed by Ogden Codman Jr., when the house was built).

Wharton designed these essentially sculptural Grass Steps, which lead from her Flower Garden, up to the back terrace of the House.

We’ll finish our touring today in the village of Stockbridge, Massachusetts…

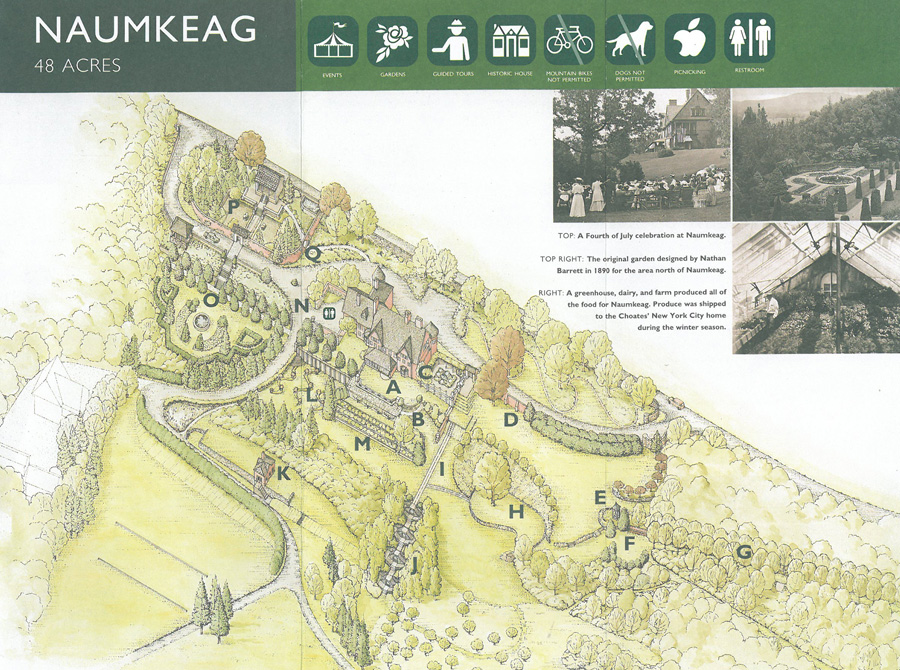

…which is a 15 minute drive south of The Mount. Our destination is Naumkeag, landscape architect Fletcher Steele’s most important creation, and the sole, intact example of the more than 700 gardens that he designed over his 60 year long career.

A multi-million dollar restoration of the gardens at Naumkeag is underway. Over the past two years I’ve watched the progress of reconstruction.

In June of 2013, the Blue Steps were being totally rebuilt, while an entirely new grove of birch trees was being planted.

And seeing separate areas of Naumkeag as they’ve been torn apart and then remade has helped me to understand that Fletcher Steele was not just a garden designer. Instead, in his best and most mature work, he became a sculptor, whose materials were dirt and stone and metal and trees.

From 1928, when Steele began The Afternoon Garden, his first commission at Naumkeag…

…until 1955, when the gardens for his client Mabel Choate were finished, his design philosophies evolved. In fact, when considering Art Deco and Modernism in American gardens, Fletcher Steele is the key figure. For 1928’s Afternoon Garden, Steele enclosed the terrace with incongruous but delightful interpretations of Venetian mooring poles, and he anchored the space with a traditional statue.

But just seven years later, his design for the nearby Oak Lawn reflected a pared-down modernism.

The garden areas at Naumkeag don’t all meld together to make a coherent whole. Rather, Steele’s disparate creations are mounted upon the land, almost as if they’re enormous sculptures. And each of those uniquely-styled constructions represents a different point along a timeline, as Steele’s thoughts about decorating the landscape developed.

The Blue Steps, Steele’s most acclaimed design…which he built in 1938… are usually photographed up close. Viewed without reference to Mabel Choate’s home and the other garden areas, the Blue Steps seem like a gateway into a magical world. A wider view, however, reveals the Steps to be the giant sculpture that it truly is…a sculpture that has no real stylistic affinity for its surroundings, but which, instead, drapes itself glamorously and seductively down through the center of a grove of imported birch trees.

The Steps were built because Mabel Choate wanted a direct but safe pathway down the steep hill that separated her house from her vegetable garden. As was always the case when Miss Choate posed a landscaping challenge to Mister Steele, the resulting design was far larger, and vastly more expensive than what she’d asked for. But Mabel had deep pockets, and an open mind, and so she allowed Fletcher to stretch his imagination—and her bank account—to the limits. Few garden designers have ever had such generous patrons as Mabel Choate. When we visit the gardens that Fletcher Steele made for her at Naumkeag, we should think of her often, and gratefully.

In late afternoon, the shadow-play on the Western-facing Blue Steps adds an extra dimension to the design. In each of Steele’s garden areas at Naumkeag, he paid close attention to the casting of shadows.

In 1953, Steele’s Rose Garden — his final commission at Naumkeag — was begun. We Gardeners know that rose bushes, past their blooming-prime, always manage to look scabrous.

But Steele’s clever Rose Garden design distracts us from dwelling upon bloom-free bushes, and with just a few wavy lines of pink gravel, he created a garden that looks good in all seasons. The Rose Garden design seems utterly modern, but is based upon ancient Portuguese patterns of laying paving stones.

Along with making a nod to an Old World decorative tradition, Fletcher Steele’s primary intention was for the curves of the Rose Garden beds to echo the rhythms of the Berkshire Hills.

Just as he had done with the edging on the Oak Lawn, Steele etched the contours of the horizon itself into the soil of Mabel Choate’s garden. This is earth-shaping in its most refined form. Where the conceptual and the sculptural are perfectly joined. Where Idea and Physicality are united.

And so, instead of using classical sculpture to declare that he and Miss Choate were as strong as Hercules and as wise as Athena, Fletcher Steele’s most abstract constructions, which mimic the profiles of the nearby Berkshire Hills, quietly announce that the makers of the gardens at Naumkeag were at one with the land itself.

And now, a Prosaic Post Script, for today’s final design-thought:

This past June, in England, Amanda Hutchinson led me to the spectacular gardens at Nymans [Note: I’ll write at length about Nymans, in a future Armchair Traveler’s Diary.] …

…in West Sussex, which surround the shell of a burnt-out manor house. The charred ruins weren’t demolished, and instead were recycled to become giant garden ornaments. I was entranced by the romantic landscapes, and by the superb displays of plantsmanship. But as I prepared to leave, I came upon this Insect Hotel, which was tucked into a back alley, next to a huge pile of cooking compost.

In nearly every garden I’ve visited in England over the past several years, I’ve found an Insect Hotel. Each of these constructions looks different, and reflects the hand of its creator. Some Hotels are designed as nesting sites for insects, while others provide space for hibernation. Some target a specific tenant, like lady bugs, or butterflies. The Hotels can house predatory, as well as pollinating insects. In every instance, Insect Hotels are functional, inexpensive to make, and represent a charming synthesis of art and ecology. I’d like to propose that we all begin building little temples like these, for our parks, and for our own gardens.

Another Insect Hotel, at Packwood House (I’ll write about the formal gardens at Packwood, in a future Diary).

Ideally, any decoration which we add to our landscapes should be more than just a generic object that’s been acquired from an art gallery or a garden supply center. And we don’t necessarily need to perpetuate antique notions about garden statuary…not unless those classical images carry messages which resonate personally. ( Witness my garden’s Hermes: the deity who protects travelers and writers…I think of Hermes as my Travel Insurance. ) But each of our garden embellishments should be chosen to serve more than a single purpose. Comfortable furniture can also be sculptural.

Statuary, whether representational or abstract, can suggest a narrative while it’s also configuring a space. Home-made ornaments can be forays into self-expression, even if the end-results are less than stellar. And the horizontal sculpture in our gardens — the paths we plot, the planting beds we delineate, and the pools we dig — can always be designed to be far more than just simple infrastructure. The key is that we must first know ourselves. Then we must carefully observe the lay of the land, and what’s growing and living, all around us. Not until we’ve done these things can we create gardens where art merges harmoniously with the outdoors. When well chosen, art communes with the pervading spirit of a specific bit of land, while it simultaneously speaks — silently and eloquently — of the character of the particular Human who tends that land.

Copyright 2015. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

7 Responses to An Idiosyncratic Survey of Sculpture, in Gardens of the Western World