Dartmouth Harbor, with Dartmouth Castle (at the mouth of the Harbor, on the far right), and the English Channel beyond. This was the mesmerizing VIEW that greeted us, on late afternoon of June 26th, when Anne and David Guy and I first arrived at the rented house that would be our home-base, for a week’s stay in Southern Devon.

October 2015

I’m back on Terra Firma (aka New Hampshire),

after this summer’s very satisfying, month-long expedition to England, where I continued my investigations of Britannia’s landscapes, luminaries, architecture, and history. Per usual, once home, my first task (after I do some serious laundry) is to sort thousands of trip photos. My brain isn’t nearly roomy enough to store all of the nuances of the places I visit, and so, as I travel, I make exhaustive visual chronicles. Later, when I review those picture albums, a fast look at a sequence of photos allows me to completely recall a particular place, on a particular day, at a particular hour. The temperature. The humidity. How a breeze felt upon my face. How the light changed under England’s fickle skies. The moods of my companions. My thoughts (whether absorbing or trivial). All of these textures and details are resuscitated, when I pour over my photo files. I tell myself that, with enough thoughtfully-made pictures, my camera can reveal the authentic Nature of each Place. The key, however, is to gather a cornucopia of pictures, because scant selections of photos can be utterly misleading. For each place to which I journey, I’m aiming to understand its essential nature, and only by looking at my subject from many angles can I hope to begin to see a totality.

As I’ve been organizing my latest photographic trove of England’s treasures, another trove of a more personal nature has come to me.

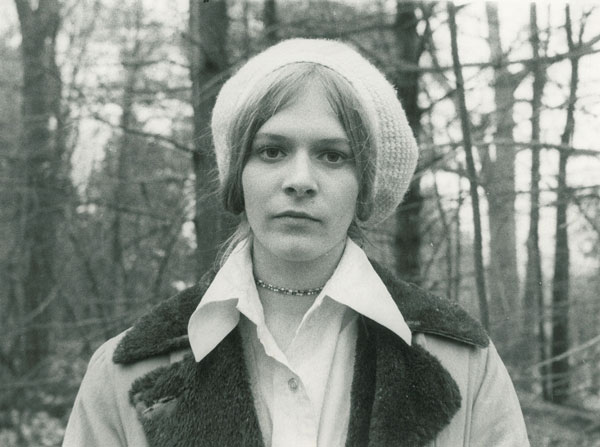

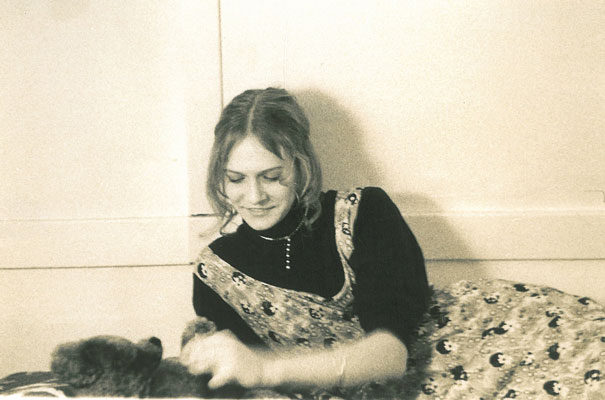

The contents of this trove have amplified my thoughts about how best to photographically reflect the truth about a person or a place. In early October of 1969, after I’d just turned 17, a schoolmate and friend (a lady who today cherishes her privacy, and so must remain anonymous) asked if I’d be her model for a photographic project. Each afternoon for a couple of weeks, my chum shadowed me with her camera as I went about my normal-after-class-time-activities.

Unlike myself (I’ve travelled lightly: except for my collection of books, and prototypes for the furniture that I design, keepsakes have tended to fall by the wayside), my friend has methodically and neatly preserved mementos, from every era of her life. At a recent high school reunion, she handed me an orange box. Inside it were those photos she’d made, eons ago. As I sifted through the little squares of slightly-musty-smelling paper, I became confused. This collection of photos seemed to consist of portraits of ten entirely different young women.

How odd, then, that those girls were all clearly wearing clothing that had once been my own. Perplexed, I reexamined each picture, but this time slowly. As I studied them, the disparate thoughts and emotions that radiated out from the sorority of faces that I was shuffling became familiar.

Befuddlement fading, I realized that I was cradling vestiges of

a complicated and mercurial girl, just as she was about to topple into the first days of her adulthood. These ancient photos of a Just-17-Me, whose parents and school assumed I’d proceed in THEIR prescribed direction, while my inclinations about what to do in life were exactly OPPOSITE, reveal a fluidity of mood and intensity of concentration which seemed, when interpreted by the camera’s lens, to continually alter my very physiognomy.

But perhaps those huge variations in my demeanor which had been captured upon film actually foreshadowed a Protean Life. In that assortment of old photos a measure of truth about my future path had already begun to be told. No single picture defined me, but, taken together, these early images became puzzle-pieces which suggested that my life was not going to settle neatly into a predictable pattern. As years have unfurled, I’ve traveled along improvised routes, failed massively, succeeded splendidly, and have finally learned that false pride must never keep me from making necessary course corrections. I’ve accumulated many more skills, fulfilled many more roles, felt much more deeply, and followed my curiosity to many more places than I could ever have imagined to be possible, as my friend’s camera shutter was clicking, and Autumn was beginning, in 1969.

And now, Patient Readers, having allowed me to make a brief and atypical digression into personal archaeology ( but a detour which nevertheless seems relevant as I’m thinking about the nature of photography…and explaining my obsession with stuffing these articles with gobs of pictures, the better to Tell the Tale ), please join me in the Present.

I, who have today been transformed into your Spry Old Lady Guide, will begin to show you MANY views of the Best Sights in Southern Devon, as they were revealed to me by my dear friends Anne and David Guy, during our recent, week-long stay on England’s southern coast.

Each summer, I look forward to spending time with my British friends. Anne and David Guy are delighted by my passion for Britain’s history, culture and landscapes, and they very charitably swear that my enthusiasm helps them to see their own country with fresh eyes. Ever-generous about sharing their Natives’ knowledge with me, over the years the Guys have led me to places in England that I’d never have found, if left to my own devices. For our explorations this summer, Anne secured an extremely comfortable (and spectacularly sited) 2-storey rental cottage in Dartmouth, for our home base.

Each day, Anne actually drove us along the street, called “Above Town,” to our cottage. When she’d meet a car that was coming downhill, she’d deftly back up until she’d reached a slightly wider part of the road. Impressive driving, to say the least….

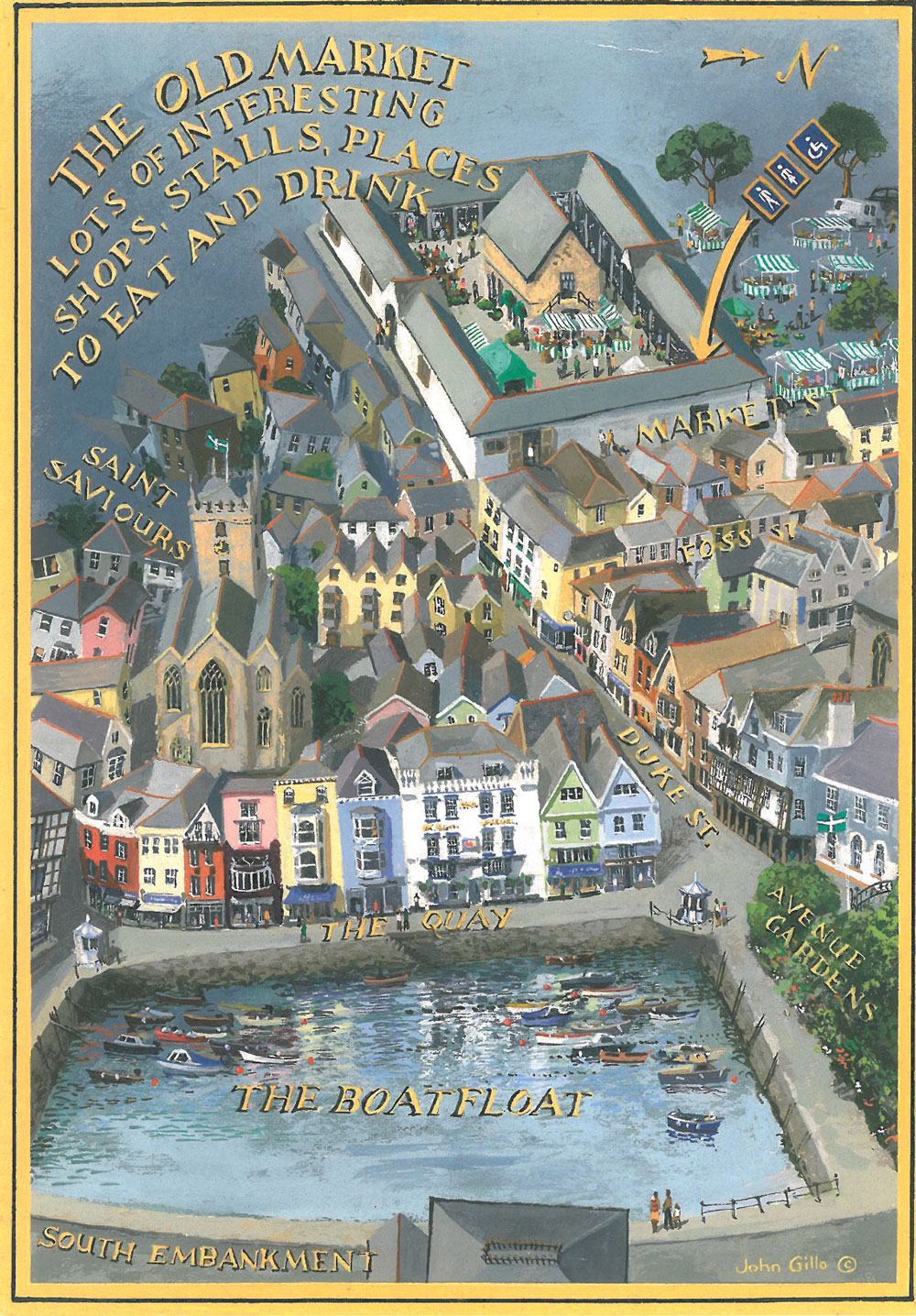

The beginning of “Above Town,” looking down toward “Smith Street.” The church tower at Saint Saviour’s Square is visible from most places in the old part of Town.

This stairway, which connects Above Town to the lower regions of Dartmouth, has over 100 steps…which we climbed regularly. Dartmouth-walking will either make you stronger, or send you to hospital.

Anne and David lead the way downhill, via Above Town. Our Restaurant Destination that evening was the Spice Bazaar: serving a refined menu of Indian & Thai food. Spice Bazaar, Church Close, St. Saviour’s Square, Dartmouth. TQ6 9DH. website: www.spicebazaar.co.uk

Before I begin my account of the first three days of our travels in Southern Devon, a bit of Dartmouth-stage-setting seems necessary. Continuing my practice of never reinventing wheels, I’ll offer smatterings about the Town, as written by Robert Hesketh in his handy booklet, DARTMOUTH: A SHORTISH GUIDE.

“A thousand years ago there was no Dartmouth. The low lying areas of what became the town were all underwater at high tide.

The site was also dangerously exposed to seaborne Viking raids. As a result, the Saxon English ignored it.”

“With its deep water and shelter, the mouth of the [River] Dart is a superb natural harbor, conveniently close to the Channel Islands,

Normandy and Brittany. The conquering Normans appreciated this, and built houses and port facilities on higher ground.”

“Development moved apace. In 1147 an international force of 164 ships assembled at Dartmouth and set sail for the Second Crusade.”

“Thirty-seven ships left the Dart to join the Third Crusade in 1190. Dartmouth played an important role in England’s wars from then on, not least in the Hundred Years War, when it sent 31 vessels to the Great Blockade of Calais in 1346. Its greatest contribution was for D-Day, 1944, when 485 ships sailed from Dartmouth to Normandy, taking a whole day to clear the port.”

The River Dart meets the English Channel. A defensive Castle has been on this site since 1387. The current Castle (seen on the right) dates from the late 15th century. The innovative 3-storey Gun Tower was the first in England to have guns as its major armament.

Dartmouth’s bonds with America run deep. During World War II, thousands of American servicemen were stationed in and around the town. But much earlier, some future Americans had also made an unscheduled call at Dartmouth’s Harbor.

In Dartmouth Harbor: Bayard’s Cove. Here, in 1620, the Speedwell docked to make repairs, before its planned voyage to the New World.

The Pilgrim Fathers anchored in Bayard’s Cove in August of 1620, to make emergency repairs to one of their ships, the Speedwell, before setting sail across the Atlantic to found their historic Massachusetts colony. The repairs didn’t hold; 300 miles off Land’s End the vessel was leaking so badly that they turned tail and headed back to Plymouth, England, which was where their voyage had originated. Passengers suspected the crew didn’t at all want to go to America and had instead been drilling holes in the ship to scupper the voyage. In the end, the Pilgrims abandoned the Speedwell, and successfully crossed the Atlantic in her sister ship, the Mayflower.

Returning to Robert Hesketh’s remarks: During the Napoleonic Wars, “with the Continent closed to tourists, the English upper class took more holidays at home. The habit stuck and the Dart Valley enjoyed lasting popularity, especially after the royal yacht, Victoria and Albert, called in 1846.

‘This place is lovely,’ wrote Queen Victoria, ‘with its wooded rocks, church and castle…It puts me much in mind of the Rhine.’”

In 1863 the Britannia Royal Naval College was established in Dartmouth, and to this day, the College is where Royal Navy cadets go for their initial instruction. After the Royal Naval College in Greenwich closed in 1998, Dartmouth’s Naval College became the only remaining school in England, for her naval officers.

The oldest parts of Dartmouth Town are situated on the steep, western banks of the River, and overlook the place where the Dart widens and prepares to pour its waters into the English Channel. Although the Channel’s in sight of Town, rarely does the scent of ocean salt fill the air. Instead, one breathes in the fresh perfume of fast-flowing river water, which is laced with notes of the grasses and crops that are grown on the high pastures and fields which embrace both sides of the River. Seagulls circle overhead as they ride thermals and squawk incessantly, while the little ferry boats which zip constantly across and up and down the River sound their horns. This cacophony of watery sounds becomes a kind of white noise, and after one has adjusted one’s ears to Dartmouth’s Voice, the Town begins to seem like a tranquil refuge from the Noisier World.

Although Anne and David made sure that all of our days in Southern Devon were filled with expeditions to wonderful sites, I also found myself being endlessly entertained by the changing views that unfolded directly outside of our windows and below our balcony, during those hours when we were relaxing in our cottage. The Town and Harbor and River and Channel and Hills and Skies seemed to be restless, and eager to demonstrate their many faces and moods.

Here, before Day One of our touring commences, a dawn to night sequence of panoramas, as seen from our “Above Town” cottage.

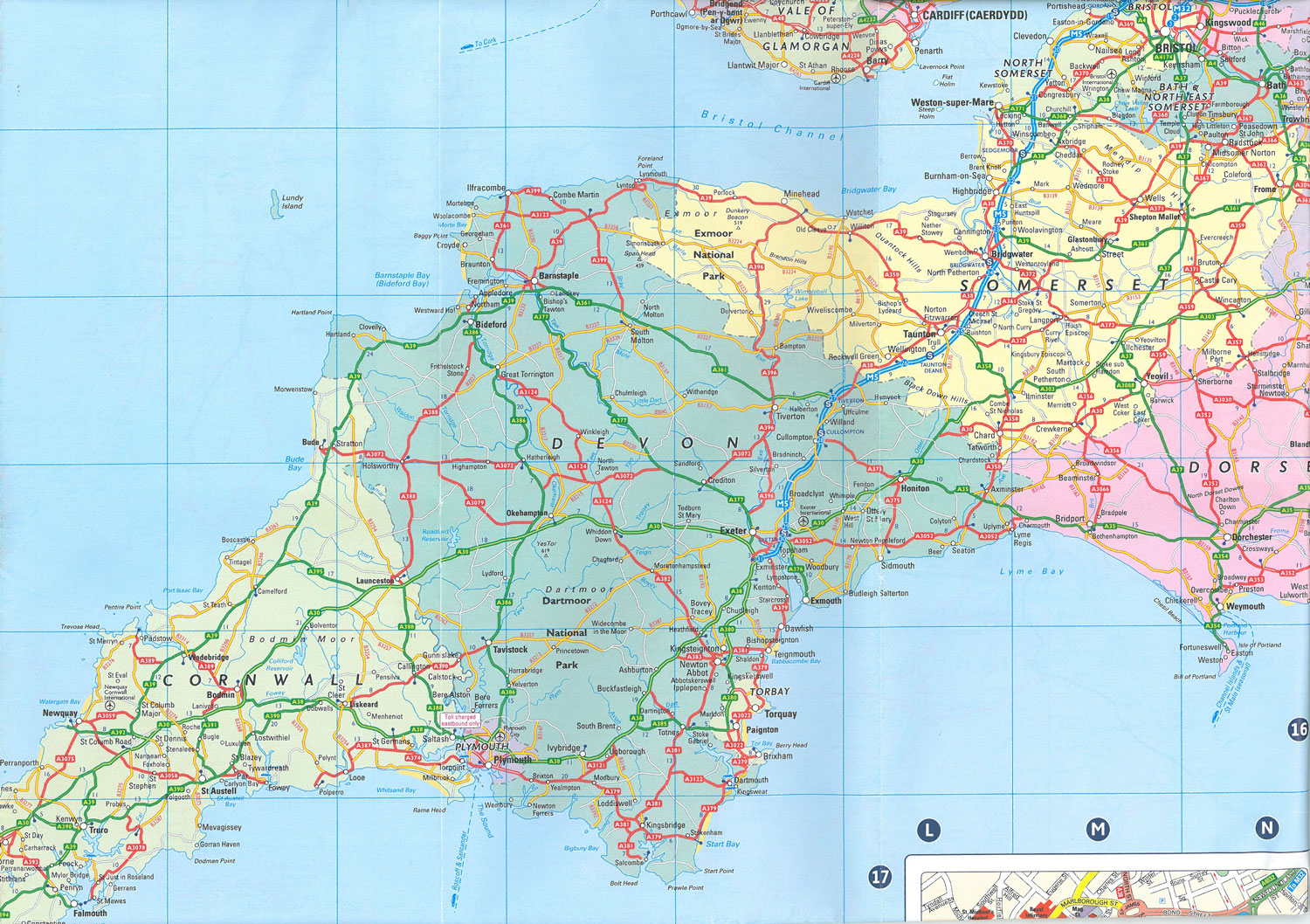

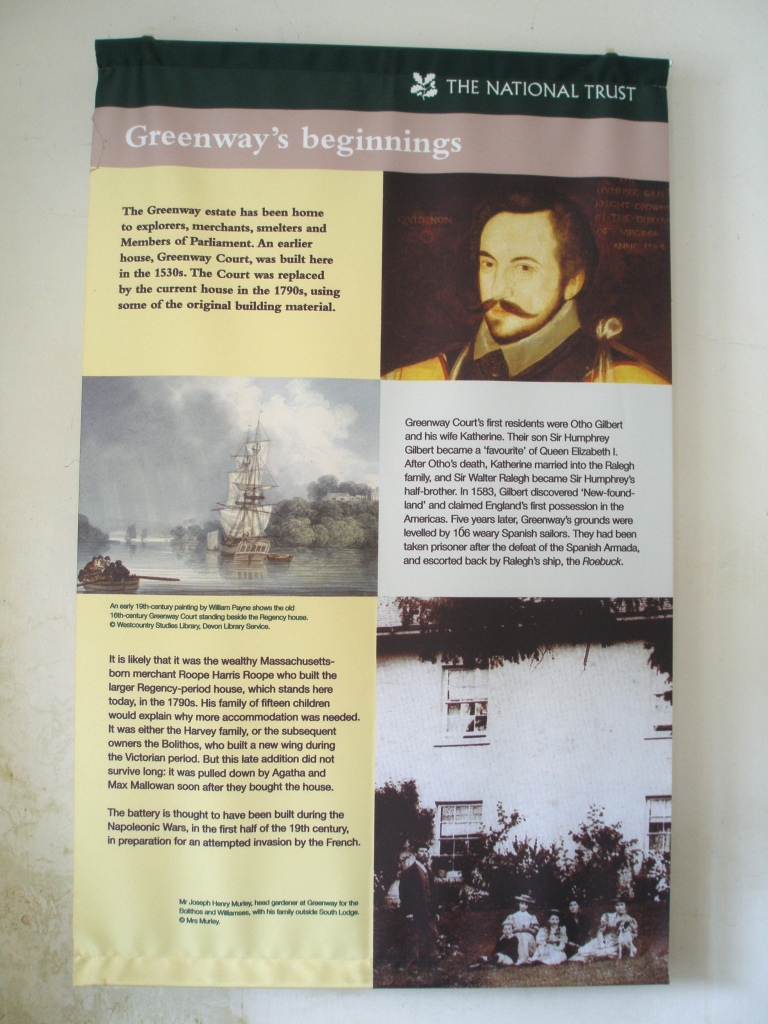

On SATURDAY, JUNE 27TH, our destination was Greenway, a manor house set within an exquisite, 36-acre tract of woodlands and gardens that are perched high above a turn in the River Dart.

Since 2000, Greenway has been owned by The National Trust. Address: Greenway Road, Galmpton near Brixham, Devon, TQ5 0ES.

Greenway’s Website: https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/greenway/

In 1530 the first of a succession of grand houses — all of them called “Greenway” — to be built upon the site was erected by the Gilberts, a renowned Devon seafaring family. In 1588, the beginnings of the gardens which surround Greenway were created, thanks to some “houseguests” of the Gilbert family, whose good friend, Sir Francis Drake had captured 160 Spanish prisoners of war and their ship.

[Note: later in this Diary, we’ll visit Buckland Abbey, Sir Francis Drake’s home.]

Drake anchored the vessel nearby, and as ransom negotiations for the ship proceeded, Sir Francis forced his prisoners to begin clearing and leveling the grounds around Greenway Court, the Gilbert’s Tudor mansion. So, although many far more illustrious folks would eventually have a hand in the creation of Greenway’s Gardens (among them Humphry Repton )…

Humphry Repton (born 1752, Died 1818) was an influential English landscape designer who is regarded as the successor to Capability Brown.

…it’s good to keep in mind those 160 pairs of Spanish hands that began the task of transforming a steep and heavily wooded hillside into the magical landscape which today shelters a nationally-significant collection of 2700 species of trees and plants. Despite Greenway’s impressive provenance (what with Francis Drake dropping by, and centuries of other illustrious Devon-ians serving as lords of the manor), the reason that Greenway has become one of The National Trust’s most visited properties can be explained in two words: AGATHA CHRISTIE.

Per Wikipedia: “The Guinness Book of World Records lists Christie as the best-selling novelist of all time. Her novels have sold roughly 2 BILLION copies.”

It was at Greenway that the Dame of Mysteries and her second husband, the archaeologist Sir Max Mallowan, made their country home, from 1938 until 1959. The interior of the house as we see it today is chock-full of their possessions. Agatha had already inherited mind-boggling collections of curios and furniture from her well-to-do parents, and the Mallowans themselves were well-traveled and world-class shoppers….as were also Rosalind (Agatha’s daughter) and her husband Anthony Hicks (who purchased Greenway in 1959, and who continued to fill its rooms with new treasures). The Christie-Mallowan-Hicks were all packrats of the highest and most entertaining order (as we shall soon see).

The delights of Greenway are further enhanced by an Aquatic Approach. From early March until the end of October, the Greenway Ferry departs from Dartmouth Town Pontoon every hour.

Greenway Ferry website:

https://greenwayferry.co.uk/dartmouth-to-greenway-house-ferry/

And so now, before our Greenway explorations begin, some glimpses of the 30-minute-long voyage from Dartmouth Harbor, northward, along the River Dart.

The tall arches of a bridge built for the still-operating Dartmouth Steam Railway line…which runs along the eastern banks of the River Dart, from Kingswear to Paignton.

Agatha Christie wrote: “One day we saw that a house was up for sale that I had known when I was young…So we went over to

Greenway, and very beautiful the house and grounds were. A white Georgian house of about 1780 or 90, with woods sweeping down to the Dart below, and a lot of fine shrubs and trees — the ideal house, a dream house.”

Per The National Trust’s guidebook to Greenway:

“Agatha Christie could not resist buying Greenway, a place she had known about from childhood, having been born and brought up in nearby Torquay. She and her husband Max Mallowan soon became very attached to the place. It became their holiday home and they spent periods here in the spring, late summer, and often at Christmas, with family and friends.”

“Agatha Christie took the advice of a young architect, Guilford Bell, to demolish the wing built in 1892. Bell also advised on the interior alterations, installing new bathrooms and introducing the cream interiors that exist today, sweeping away the gloomy and unfashionable colour schemes of the previous owners. The Mallowans were keen but not expert gardeners, and quickly became interested in the existing planting schemes.”

“Work in the garden was interrupted by the outbreak of World War II, when the house was requisitioned and initially occupied by child evacuees, and then from 1944 to 1945 by the 10th Flotilla of the U.S. Coastguard as part of the preparations for D-Day.”

“After derequisition both the house and garden needed attention. In 1947 a nursery garden was created and run as a commercial

enterprise until the end of the 20th century.”

“Greenway is also featured in at least two of Agatha Christie’s novels: as Nasse House in DEAD MAN’S FOLLY, and as Alderbury in FIVE LITTLE PIGS.”

For visitors coming to Greenway from the hamlet of Dittisham, which is just across the River, a small conveyance is available. To summon a ride, one rings a dockside bell, and Viola! This little motorboat appears.

Turn right, through the gate, to find the steep path uphill. But a shuttle IS available, for those not vigorous enough to make the climb.

Let’s see how Max and Agatha lived, shall we?

Constant streams of visitors enter the Front Hall. The brass-studded chest immediately to the right of the front door was featured in two of Christie’s books: THE MYSTERY OF THE BAGHDAD CHEST, and THE ADVENTURE OF THE CHRISTMAS PUDDING.

Display cabinet in the Front Hall. Before the property was opened to visitors in 2009, every item in the House was catalogued by The National Trust. Agatha’s daughter, Roslalind Hicks, had a particular fondness for pocket watches, snuff boxes, and portrait miniatures.

More collections in the Front Hall. (I would HATE to have to be the one responsible for feather-dusting the House Collections…..)

The Morning Room.

The two niches flanking the fireplace are filled with the Hickeses’ collection of botanical porcelain. The rest of the room was decorated with ornaments that Agatha inherited from her grandmother, and from her parents.

The Winter Dining Room. The plasterwork over mantle depicts the Old Testament story of Daniel’s three friends being thrown into the fiery furnace for refusing to worship a golden idol (quite a domestic fireplace decoration eh?). This plaster relief is thought to have been part of the site’s original Tudor mansion. How it came to be saved, and then reinstalled in the current House is a mystery.

Transom window above the door between the Winter

Dining Room & the Service Corridor. The bells on the wall were used to summon the House’s servants.

The commodious Inner Hall is thought to have originally been a billiard room. When the Mallowans purchased Greenway, their architect Guilford Bell transformed this space into yet another gallery for the display of their Treasures.

The Dining Room, which measures 31 feet long by 19 feet wide, is by far the least cluttered and most tranquil space in the entire House.

Agatha Christie’s favorite menu included hot lobster, followed by blackberry ice cream. Here’s her Lobster-Serving Dish.

An extremely disturbing doorstop, in the Dining Room: just a little reminder that the smiling, gray-haired Lady of the House had a mind that often wandered into Exotic Realms.

Per The National Trust’s guidebook: “The Library’s extraordinary frieze was painted by Lt. Marshall Lee in 1943, when the house was

occupied by Flotilla 10 of the U.S. Coastguard. It depicts all of the significant events of their war, starting at Lt. Lee’s base in Key West, FL, and ending with an image of Greenway perched high above the river with an Infantry Landing Craft in the river below.”

Christie’s mahogany-seated toilet. I’m not sure that Agatha would be delighted to know that mobs of tourists now gawk at her privy…

Originally a bedroom, the Sitting Room later became Max Mallowan’s writing room. When Agatha was at Greenway, there’s no evidence to suggest that she plied her author’s trade. Of course, Agatha did weave elements of their country home into her mysteries, but her time in Devon was not spent in toil at her typewriter.

We headed back down the Main Stairway, where we admired its groined ceiling, and arched clerestory window.

For a therapeutic blast of fresh air, we’ll proceed outside, into the sunshine of Greenway’s south-facing Gardens!

Greenway’s 36 acres, on a promontory above the River Dart, feel utterly at one with the greater, Devonian landscape. As mentioned, the retaining walls and paths by which Greenway’s steep slopes were made hospitable for future gardens were built in 1588 by Spanish prisoners. Over the following 400 years the nine families who then each owned Greenway continued to tame the land and develop the gardens. But the layouts of the gardens which we visit today are still basically those which were refashioned in Humphry Repton’s relaxed and picturesque style, from 1791 until 1832. Subsequent owners embellished the garden with the plantings of shrubs and trees that still flourish, but a few ancient specimens also survive, particularly a Cork Oak (in the Camellia Garden), which is estimated to be 300—350 years old. This is a garden that’s literally rooted in history; a place where past and present resonate, and meld seamlessly.

The Croquet Lawn is directly to the west of the House. This area is dominated by a Magnolia grandiflora.

Reinvigorated after enjoying lunch at Greenway’s Barn Cafe, we entered the South Walled Garden & Vinery, and began our garden explorations.

And WHAT, pray tell, is a BOTHY? It’s a Scottish Highlands term for a VERY basic gardener’s cottage. By the time of the Mallowans, this hut was used to store coal and firewood.

This extensive Glass House was built against the northern wall of the South Walled Garden by Richard Harvey, a wealthy copper magnate. Harvey owned Greenway from 1852 until 1882, and during those years he restored the lodge and stables (where the Barn Cafe and Gift Shop currently are), built glass houses within the pre-existing walled gardens,

and thinned the outlying forests, where his gardener, J. Coudray, then introduced specimens of exotics, including acacias, clianthus, sophora, and myrtles.

The view from outside the Glass House, across the lawn of the South Walled Garden, toward the white chimneys of the main House. This Garden — a full acre — was originally a kitchen garden.

The Herb Border, in the South Walled Garden. Against the high wall behind the herbs climbs an ancient Wisteria sinensis.

The North Walled Garden continues today, as a working nursery where plants are propagated for Greenway’s gardens. This Glass House was built by Susannah Harvey in the 1870s, and in this space she grew Peaches and Nectarines.

Our first view of the Fernery’s Fountain. Property records indicate that this area of the estate already existed in 1791, when Edward Elton ( a merchant, adventurer, and MP ) purchased Greenway. Elton immediately commissioned a re-design of most of the grounds, with guidance by Humphry Repton.

Leaving the Fernery, we found a towering Monkey-Puzzle Tree (aka a Chilean Pine, which can grow to be 130 feet tall).

From the Top Garden’s path, we had this fine view toward the hills, on the western side of the River Dart.

And YES, due to Southern Devon’s mild climate, palm trees DO flourish. (Note: you’ll see MANY more tropical plants, when I publish Part Two of my Southern Devon journals.)

Our next stop: the Boat House, which is also known as “Ralegh’s Boat House.” Sir Walter Ralegh was half-brother to Sir John Gilbert (who belonged to the family who first settled at Greenway). The current Boat House dates from late Georgian or early Victorian times.

Putting her vacation home to good use, in DEAD MAN’S FOLLY Agatha Christie used the Boat House as the setting for the strangulation of her fictional character Marlene Tucker.

In Real Life, the Boat House is a calm (and not at all murder-inducing) place. The National Trust has recently begun a campaign to raise funds for the restoration of the Boat House, but I rather like it in its current, disheveled condition.

Leaving the Boat House, we proceeded to the Battery, which I confess became my favorite spot at Greenway.

The Battery dates from the 18th century and is thought to have been built as a Napoleonic defense in the 1790s. (I think that EVERY

riverside garden should have a Battery….)

On SUNDAY, JUNE 28TH, Anne and David and I agreed that a day of wandering through Dartmouth’s streets and ambling along the town’s waterfront and riding the River’s ferry boats would be most relaxing . And so, without agenda, we went forth, into a misty and sometimes rainy morning. What follows is a scrapbook of Dartmouth; one which will, I hope, give you a vivid sense of the Place.

Although we’d cooked ourselves entirely healthful breakfasts, once our feet had hit the slippery pavements, our brains and stomachs

immediately demanded caffeine, sugar and butterfat … which necessitated a visit to Saveurs, Dartmouth’s best patisserie.

My photos from our caffeine-sugar-and-butterfat-fueled Ramble:

The Cherub Inn, built circa 1380, is the oldest secular building in Town, and the only complete medieval house.

In 1951, Christopher Milne — utterly sick of being known as Christopher Robin — fled Pooh’s Corner and East Sussex, and settled in Dartmouth, where he established his Harbour Bookshop. Christopher refused to EVER stock ANY of the Pooh stories; his bookshop is now closed, but not due to its boycott of A.A.Milne’s publications.

Later on, we’ll take the Lower Ferry, over to Kingswear. Note that this Ferry isn’t self-propelled. Instead, a nimble little Tugboat does all of the work.

The street at Bayard’s Cove (often used for location shots in period films) is lined with attractive 17th to early 19th century homes.

Here, a barometer.

Gull Cottage: Site of the former home of Sir Humphrey Gilbert. Sir Humphrey was born at Greenway (remember, the Gilberts were the first family to settle there). Humphrey became a favorite of Elizabeth Ist, and took possession of Newfoundland for his Queen.

To propel us across the River Dart, the Tugboat temporarily assumes a position that’s perpendicular to the Ferry….quite a maneuver to witness !

Can you imagine that Amtrak would name a passenger coach the LADY CHATTERLEY? I think not. Only in England could this happen…that’s why I love the place so much.

Done with our train spotting, we headed back across the River, via a different Ferry; this one leaving from The Royal Dart, and for foot passengers only.

The Royal Dart dates to the 1700s, when it was known as the Plume of Feathers Public House. When the railway came to Kingswear in the mid 19th century, Feathers were re-fluffed, and transformed into the Station Hotel. In the 1860s, another name was bestowed, the Yacht Hotel, and after Queen Victoria attended a Regatta in the 1870s, the Hotel became the Royal Dart. Now a museum containing Naval artifacts (due to the building being used during World War II as a command post), the Royal Dart is much in need of restoration.

Returned to Dartmouth, we continued along the waterfront, toward the Town Jetty.

Dartmouth’s profusion of Little Green Men gave me pause. ‘Twas time for me to understand just WHAT these pagan images signified. Indirectly but ultimately, the best explanation of those Little Green Men came to me via David Guy, who is absolutely the best-read person I’ve ever known. During our Dartmouth stay, David, considering my predilection for England mystery writers, suggested that I try a series of books written by Christopher Fowler.Fowler’s wonderful Peculiar Crimes Unit mysteries, featuring his superannuated detectives, Bryant and May, have now completely hooked me. Christopher Fowler does not just plot stories of diabolical intricacy and subversive humor ; into each of his PCU sagas, Fowler also weaves oodles of deep background, about English history, culture, and geography.

A while back, as I was greedily plowing through BRYANT AND MAY ON THE LOOSE, the seventh book in the ongoing PCU Series, I was delighted to read this passage, as spoken by

Arthur Bryant, the more eccentric of the two detectives:

” ‘ Well, there’s a sinister side to all of this.’ Bryant’s blue eyes glittered, as he found another lithograph. ‘George-a-Green, or

Herne the Horned One, is also Jack in the Green or the Green Man, the spirit of vegetation. The Green Man is a story that predates Christ. Uniquely, it has its roots in both pagan and Christian history. The legend tells how the dead Adam had the seeds of the tree of knowledge planted in his mouth. From this mix of fertility and soil grew a sinister god, the Oak King, the Holly King, the

Green Man — the symbol of death in life. The Green Man is found in a great many English churches. He appears both in church carvings and at May Day celebrations, as a sort of primeval trickster, a symbol of spiritual rebirth, but also as a vengeful rapist and bloodsucker. The Green Man is a forest creature with the power to wipe out cities and return them to nature. He destroys men by unleashing natural forces upon them, and reappears when the earth is threatened. He can be benign and healing, but there’s a wildness about him, a dangerous cruelty — and a terrible madness. ‘ ”

All of this essential (for me, at least) Green Man Lore now acquired … from just one more of the hundreds of colorful and cultural sidebars (which are nevertheless relevant to the Plot) that Christopher Fowler somehow incorporates into a paperback detective story! Pure serendipity. For lovers of well-wrought mysteries (and — with apologies to Agatha Christie — because I’ve got to say that Christopher Fowler is a FAR better writer than the beloved Mrs. Mallowan), there’s endless fun to be had by solving crimes, alongside Christopher Fowler’s Bryant and May.

Forgive me for yet another of my digressions….but it’s this unexpected gathering together of cultural bits and pieces that makes the Traveling Life so intoxicating.

Now, back to our Dartmouth-town walk:

Just around the corner from the Royal Castle Hotel is the Butterwalk, which consists of 4 timber framed houses that date from 1628 to 1640.

Much-contented with our local perambulations, we retired for a few hours to our Cottage on Above Town, where I napped and then caught up with my postcard-writing. Later that afternoon, when rain clouds had finally dispersed, Anne drove us southwards over five miles of hair-raisingly serpentine and narrow roads, to Slapton Sands.

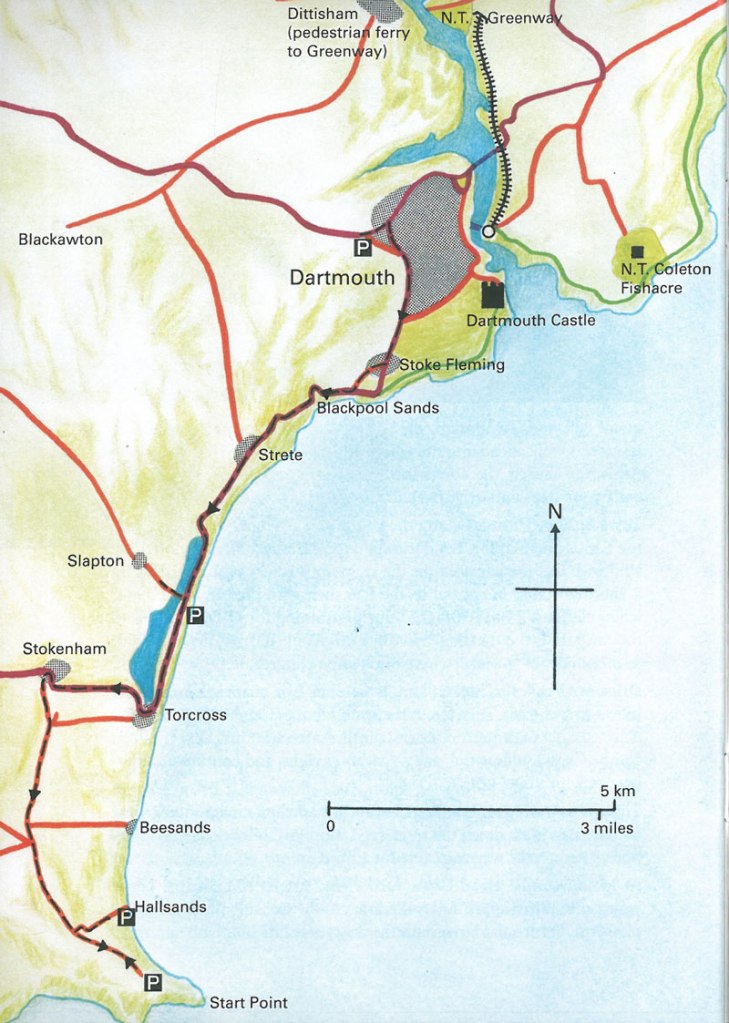

Map of Slapton Sands (also known as Slapton Beach).

Image courtesy of Robert Hesketh’s DARTMOUTH: A SHORTISH GUIDE.

The tranquil expanse of the shingle beach of Slapton Sands, and the adjacent lake, bird sanctuary, and emerald hills of the National Nature Reserve called Slapton Ley give no hint of the horrors that once took place here.

Map of Slapton Ley. Slapton Ley has the largest natural lake in south-west England. Although it is separated from the sea by a very narrow bar of shingle, the lake is entirely freshwater.

Website: www.slnnr.org.uk

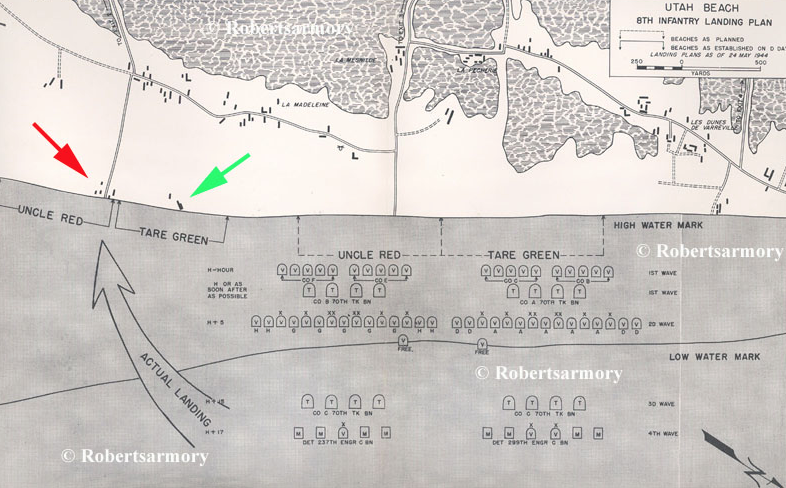

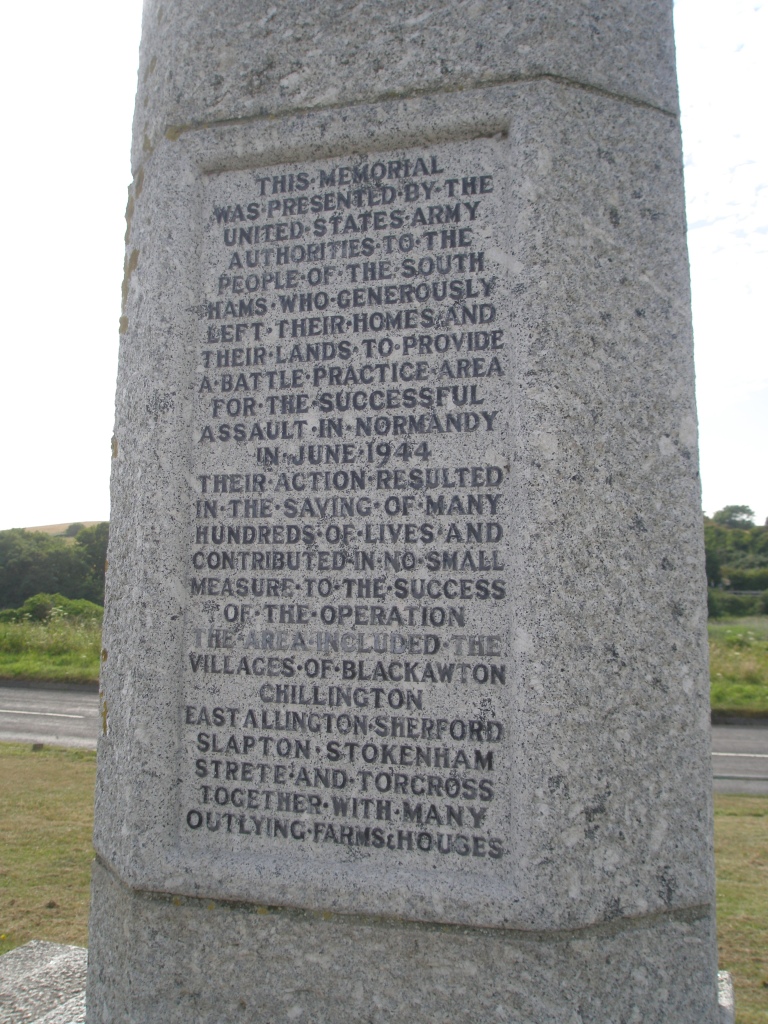

As I’ve mentioned, during World War II thousands of American servicemen were stationed in and around Dartmouth. In ultra-secret preparation for the planned, D-Day invasion of Normandy, the British Government, in coordination with America’s General Dwight D. Eisenhower (who was also the Supreme Allied Commander), requisitioned all of the land and seashore in the vicinity of Slapton and Torcross. The beach at Slapton Sands, with its similarities to France’s Utah Beach ( a gravel beach, and a nearby lake, separated by a narrow strip of land)…

…was chosen for military training exercises. With very little prior notice, and without being given any reason, the English inhabitants of eight entire villages, as well as those who lived on all of the surrounding farms, were ordered by the Military to evacuate the area. The populace (numbering approximately 3000 humans, along with countless farm animals) did so with speed and silence … and with an acceptance and grace which today would be unimaginable.

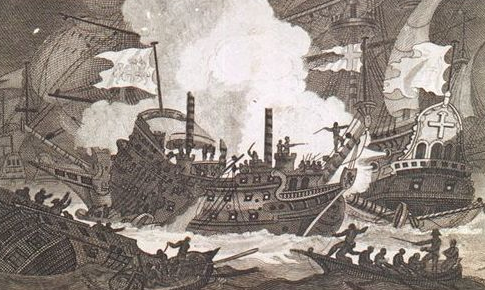

In late December of 1943, 30,000 Allied servicemen and scores of ships began using Slapton Sands for their landing exercises, which had been named “Exercise Tiger “ (also known as “Operation Tiger.”). This enormous endeavor had somehow to be accomplished without attracting the notice of spies, or of the German E-boats that prowled incessantly alongside England’s shorelines. [Note: the Germans called these boats Schnellboot, meaning “fast boat.” E-boats were heavily armed, and sleek: able to sustain a speed of 50 mph.]

Landing exercises continued apace until April 28, 1944, when, in an instance of everything-possible-going-wrong, a forward-rolling disaster of epic proportions began. As a practice assault upon the Beach commenced that morning, a series of missed communications sent American soldiers who’d already made their beach landing directly into the zone where shells launched from the British heavy cruiser HMS HAWKINS were exploding. General Eisenhower had correctly asked that his beach-storming troops become acclimatized to the sounds and smells of live ammunition. The point was for the live ammunition to whiz over the heads of the troops, as they waded ashore. Landside officers were given the job of coordinating timing: the troops were not meant to have reached the shore until all shells had detonated. A white tape was also to have marked the line on the beach beyond which the Americans were not to proceed, until the beach-masters had declared the area safe.

Unsynchronized firing of the shells, along with a delay in the start-times for the American landing ships, sent 197 American soldiers to their deaths: directly into the line of friendly fire.

But the horrors of April 28th had only just begun. A swarm of nine German E-boats that were lurking in Lyme Bay happened upon the under-protected convoy of American troop ships that were part of a follow-up landing exercise. Earlier that night, British ships had spotted the E-boats, but, in another spectacular

failure of communication, had not alerted the American convoy about the imminent threat. As American ships approached the Beach, the E-boats attacked. Within minutes, four American ships were destroyed or severely damaged: 749 American Army and Navy men were either killed outright, or drowned in the frigid waters.

But a single miracle can be said to have occurred on that day.Blessedly, the Germans didn’t draw the conclusion that this massing of British and American forces at Slapton Sands had a greater meaning: that this military exercise on the shores of Southern Devon could be in any way a precursor to an Allied invasion of German-occupied France.

And so, with 946 American dead (and countless more wounded), secrecy about the day’s calamity became the overriding and ghastly necessity. To acknowledge what had occurred would

inevitably alert the Germans that the Allies planned soon to mount a sea-attack upon France. The dead were hastily buried en masse; dug down there to lie, unnamed and hidden, beneath the green hills that overlook the Lake. The day’s casualties went unannounced; not until August of 1944, and after the successful assault of D-Day, were the dead named, and, even then, those who had perished at Slapton Sands were reported to have died during D-Day operations.

The lake at Slapton Ley is separated from the shingle beach by a spit of land. The hills that rise behind the lake are the unmarked and final resting places of many of the 946 Americans who died during Exercise Tiger, on April 28, 1944.

After the conclusion of the War, the catastrophe at Slapton Sands was not so much covered up as it was forgotten.

Historians concentrated upon the larger and, in the American and English views, the more positive aspects of World War II. Official histories did of course mention Slapton Sands, but, without any gravestones to mark the final resting places of those 946 Americans — and in the absence of the tales of those who had survived the dual disasters on April 28, 1944 (the survivors were sworn to secrecy) — the non-military-history-reading Public therefore had no reason to suspect that the hideousness of war had ever touched the shingle beach, there in beautiful, bucolic Devon.

Not until the 1970s, when Devon resident Ken Small discovered traces of destroyed ordnance while beachcombing at Slapton Sands,

was any effort then made by either England or America to memorialize the 946 servicemen who had died there and been forgotten.

Detail of the Sherman Tank, which is in remarkably good condition, despite having been for decades under seawater.

I’m in Torcross, looking northwards up along the long curve of Slapton Sands. “Sands” is misleading: the beach consists of shingle (small stones).

American Troops making practice landings on Slapton Sands, during rehearsals for the invasion of Normandy. Photo courtesy of Wikipedia.

Anne identified these scrubby purple flowers that blanket the dunes at Slapton Sands as Echium vulgare (also known as Vipers Bugloss !! ) Photo courtesy of David Guy.

When I first beheld the Sherman Tank at Torcross, and began to learn about what had happened there at Slapton Sands on April 28th in 1944, I wanted to weep. Somehow, it seemed incomprehensible that in this sublimely beautiful place, human beings had once again imposed such ugliness upon themselves, and upon the land. Mother Earth deserves better, and we, her eternally ungrateful and terminally heedless children, should have, long-since, learned to be wiser, and kinder, and less war-like. Sometimes I despair….

But, thanks to the peculiarities of English traffic signage, my grim mood soon lifted. Heading back to Dartmouth, we passed a small construction zone in the village of Strete.

I laughed and remembered how, three years ago in neighboring Dorset, I’d been appalled by my first encounter with such Alarming Red Signs. I’d shrieked, and asked Anne and David if entire districts in England might be removing cats’ eyes. They’d reassured me that Cat’s Eyes are reflective, raised pavement road markers which mark the lanes of the road. When road resurfacing needs to be done, the flexible rubber domes of Cat’s Eyes are removed, and afterwards replaced into the new Tarmac. What a relief it was to learn that the sadism against animals which those signs had initially made me visualize was in fact only a routine sort of road maintenance.

The anthropomorphically-named Cat’s Eye. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

I hopped out of the car and took this picture, just to prove that the removal of man-made Cat’s Eyes is a routine event, in the United Kingdom!

On MONDAY, JUNE 29th, Anne and David and I drove westward, toward Plymouth. Our day was to be a long wallow in three of Southern Devon’s most exquisite landscapes.

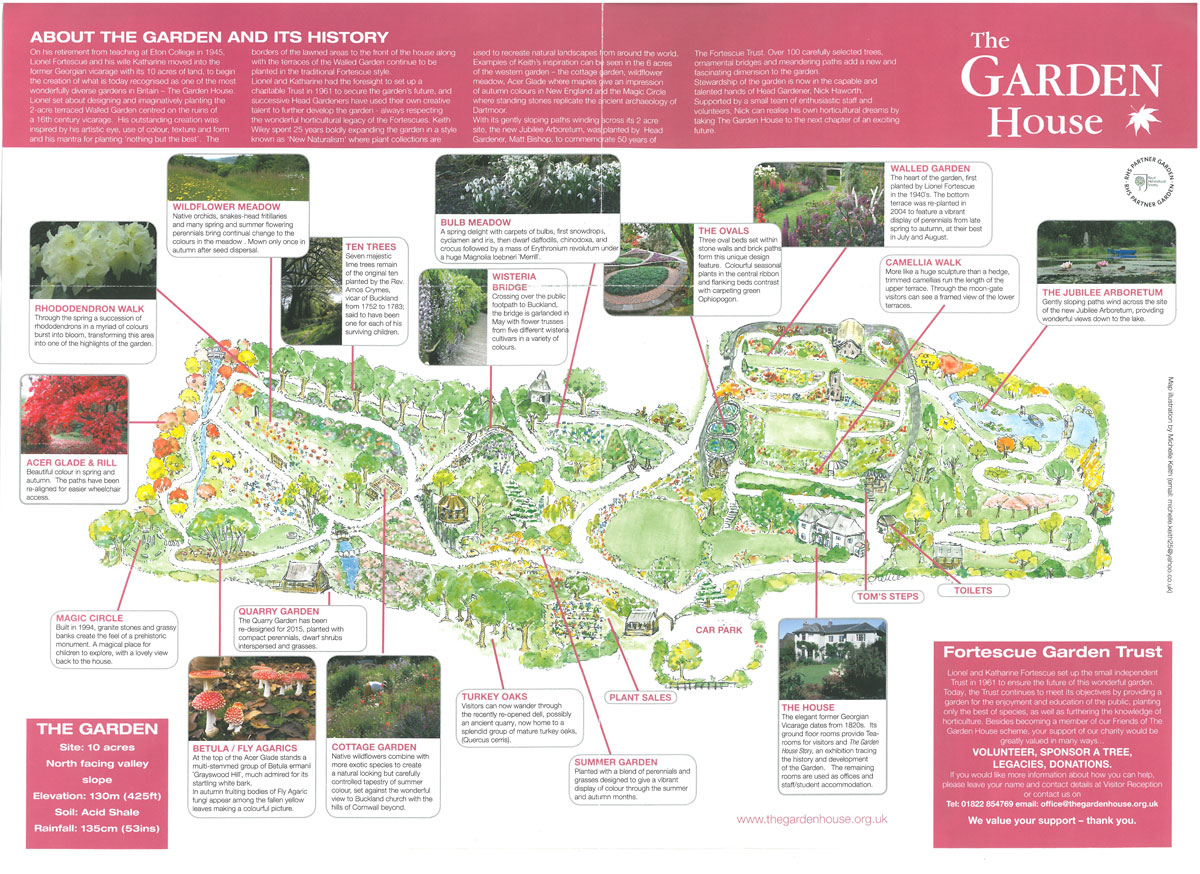

Our first stop: the wonderful, Fortescue-family gardens at The Garden House, in Buckland Monachorum, Yelverton, near Tavistock, Devon. PL20 7LQ.

Open Daily, from May 1st through August 1st.

Website: www.thegardenhouse.org.uk

For our Monday’s adventures, Janet Hardwick and Barry West had traveled down from the Midlands to join me and the Guys. Over the years, Anne’s mother Janet

has on many occasions welcomed me as a guest into her home, where she pampers me to excess (although I plead with Janet not to fuss!). My annual trips to England are not made expressly to add new chapters to my lifelong project of self-education; each time I fly Eastward across the Atlantic I’m also looking forward to spending another week or two with my lovely, adopted, English family.

The 10 acres of gardens at The Garden House offer a sumptuous horticultural immersion in color, scent, texture and form. For an Introduction, I’ll quote just a bit from their “About the Garden and its History” pamphlet:

“On his retirement from teaching at Eton College in 1945, Lionel Fortescue and his wife Katherine moved into the former Georgian vicarage with its 10 acres of land, to begin the creation of what is today recognized as one of the most wonderfully diverse gardens in Britain: The Garden House. Lionel [first] set about designing and imaginatively planting the 2-acre terraced Walled Garden, centered on the ruins of a 16th century village. “

“Lionel and Katherine had the foresight to set up a charitable trust in 1961, to secure the Garden’s future, and successive Head Gardeners have used their own creative talent to further develop the garden…always respecting the horticultural legacy of the Fortescues. Keith Wiley spent 25 years boldly expanding the garden in a style known as ‘New Naturalism,’ where plant collections are used to recreate natural landscapes from around the world. Examples of Keith’s inspiration can be seen in the 6 acres of the western garden: the cottage garden, wildflower meadow, Acer Glade…and the Magic Circle. With gently sloping paths across its 2 acre site, the new Jubilee Arboretum was planted by Head Gardener Matt Bishop, to commemorate 50 years of the Fortescue Trust. Stewardship of the garden is now in the capable hands of Nick Haworth.”

Please now: join me as I retrace our steps through the Gardens.

This Map — somewhat different from the Map illustrated on the Garden’s pamphlet — is posted at the Garden’s Ticket Booth.

Just beyond the Ticket Booth, we were enveloped by lushly-planted borders.

In the distance, a bit of the circular Front Lawn is visible.

But before ANY garden-tromping could occur, we needed to indulge in the Tea Rooms’ top-notch cakes and coffees. Image courtesy of The Garden House.

From behind the House, we peered down to the Tennis Court Lawn, which is on an upper terrace of the Walled Garden.

A Moon Window has been carved through the high hedge which separates the House from the Bowling Green Terrace

From the western end of the Bowling Green Terrace one first passes through

a rustic summerhouse, which opens onto this extraordinary cascade of steps, ramps and raised beds: called THE OVAL GARDEN.

At the lowest point in the Oval Garden: a shaded, circular terrace, with a view of the Bottom Terrace Garden.

From the Oval Garden’s shaded terrace, a view uphill, toward the Summerhouse at the top of the steps. The precision with which these dry-laid stone walls were constructed is amazing.

The Walled Garden’s Tennis Court Lawn, with a view uphill, to the Main House.

Foxgloves were in their full glory.

Blossoms (which we were too late in the season to see), on the Camellia Walk. Image courtesy of The Garden House.

AT the northeastern corner of the Tennis Court Lawn: a gate leading down to the Tower Ruins, and to the Bottom Terrace Garden.

At the eastern end of the Bottom Terrace Garden: the gate to the newly-established Jubilee Arboretum.

View from the easternmost end of the Jubilee Arboretum. 100 carefully-selected trees, still in their infancy, will someday grow into a beautiful forest.

As I exited the Bottom Terrace Garden through its western gate, I turned back for a moment, for one more look…..

Heading west, and uphill, I strolled along Devon Lane, the topmost path in the

Summer Garden. Before Summertime’s poppies burst into flower, this area is called the Bulb Meadow…carpeted with Spring-blooming bulbs, which appear in the following sequence: snowdrops, cyclamen, iris, dwarf daffodils, iris, chinodoxa, crocus, and Eythronium revolutum.

The Bulb Meadow, as spring blossoms arrive: carpets of Snowdrops. Image courtesy of The Garden House.

Just beyond the Dovecote, I crossed the Wisteria Bridge…with vines that were long-past their bloom-time.

This is the sight we missed, at the Wisteria Bridge: the glorious explosion of 5 different wisteria cultivars, which happens in May. Image courtesy of The Garden House.

After crossing the Wisteria Bridge, there’s this surprise of a Bamboo Grove, which encircles a Rustic Summerhouse.

Looking south from the Bamboo Grove, and across another part of the Summer Garden, we see yet another Shelter, which is perched above the brand-new Quarry Garden.

My view from the Quarry Garden’s Shelter, down over the new Quarry Garden…just planted in 2015. Compact perennials, dwarf shrubs, and tall grasses are just getting themselves established in the beds.

Farther west, we’re in the Wildflower Meadow. Native orchids, snakes-head fritillaries, and many spring and summer flowering perennials bring continual change to the colors in this part of the Garden. The Meadow is mown only once, in Autumn, after seed dispersal.

Talk about a Great Borrowed View! A distant church, as seen from within the Wildflower Meadow. Image courtesy of The Garden House.

Our visit to the Garden House nearly done, we savored the exuberant colors and textures in the South African area.

After I’d organized my photos of The Garden House — all taken this past June — I checked the Garden’s website to confirm their contact information. I found this photo of the Meadow below the Wisteria Bridge, in Autumn. Clearly, these Gardens shine, in EVERY season. Image courtesy of The Garden House. For plant-lovers, this Garden is a crucial destination.

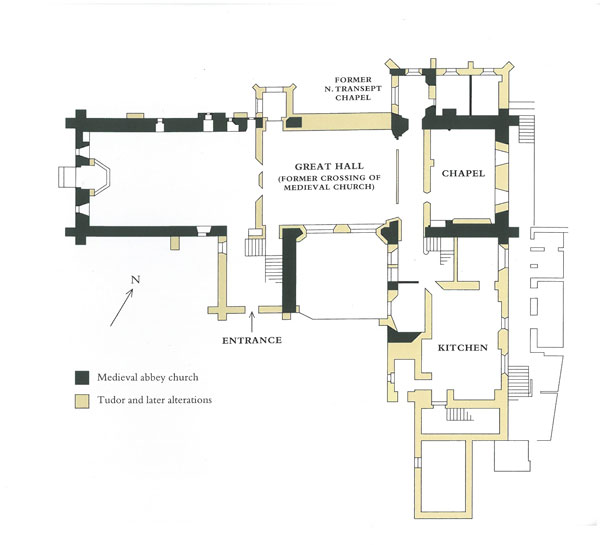

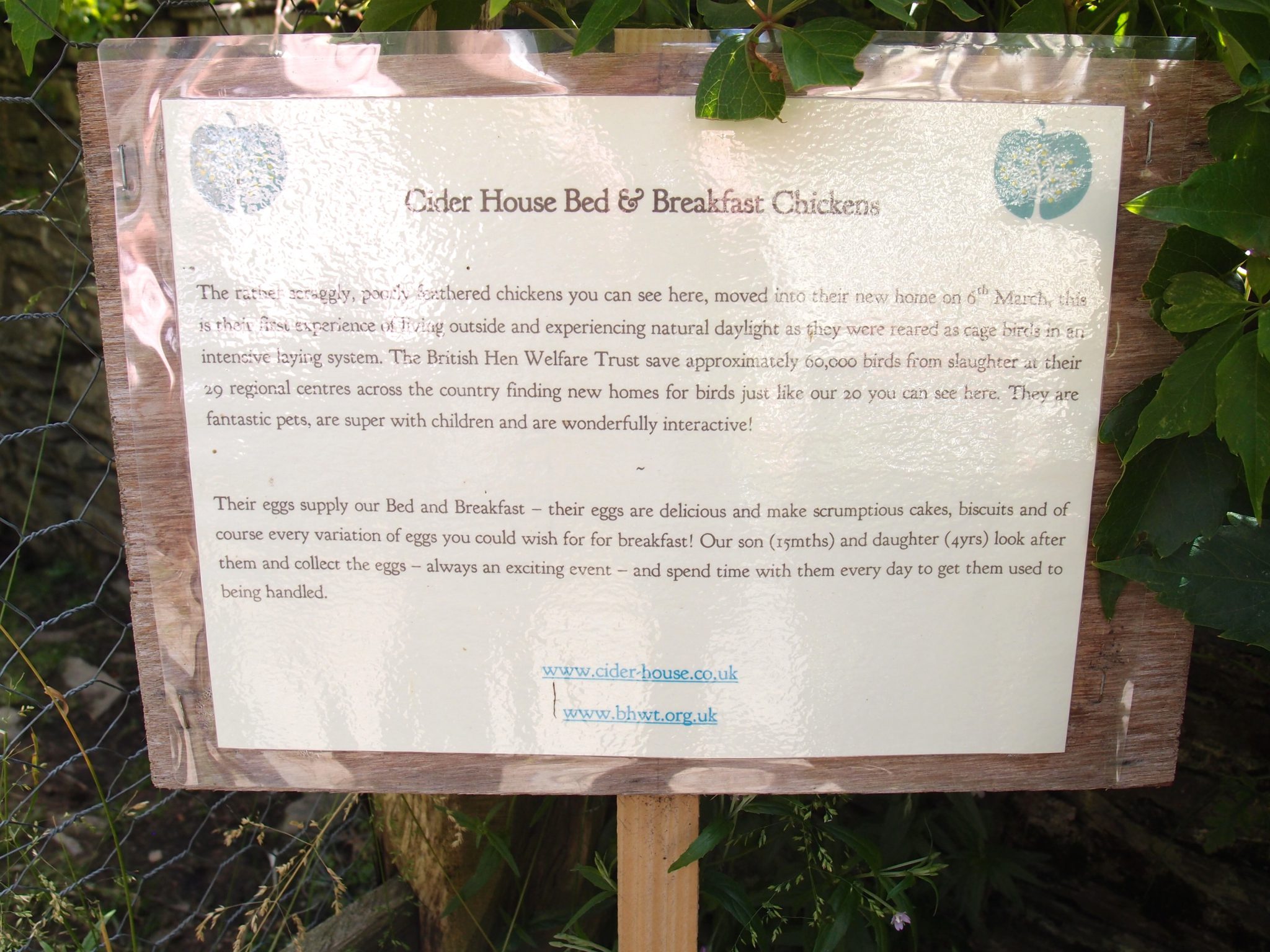

Following my two hours of blissfully-restful-total-plant-immersion at The Garden House, we made the barely-five-minute commute to nearby Buckland Abbey. Ideally, the Abbey, its Gardens, and its vast Estates should be explored over the course of an entire day. Buckland offers an embarrassment of riches. With over 700 years of architecture, history, and fine craftsmanship and art to study (including a Rembrandt self-portrait, recently bequeathed to the Abbey), along with acres of gardens, and miles of country walks to enjoy, the place begs a Visitor to Amble. Good food is available at the Ox Yard Restaurant. And there’s even an abused-chicken-rescue project going on, in a far corner of the Kitchen Garden.

Buckland Abbey was established in 1278 by Cistercian monks. In 1541, After King Henry VIII’s Dissolution of the Monasteries, the vast estates of the Abbey

(which encompassed 20,000 acres) passed into private hands and so eventually became home to two of England’s most swashbuckling maritime personalities : Sir Richard Grenville, followed by Sir Francis Drake. The National Trust opened the Abbey and its estates to the Public in 1951. Image courtesy of The National Trust

Buckland Abbey, Garden & Estate

Yelverton, Devon PL20 6EY

The Abbey buildings, garden, and estate are all open from March through October (with limited hours during the colder months).

Website https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/buckland-abbey/

Plan of Buckland Abbey’s

Gardens; and a Map of the Walks across the landscape of the Estate.

Key to Estate Walks: YELLOW=

Abbots Walk, 1 mile. GREEN=Grenville Walk, 1 ½ miles.

RED=Drake Walk, 2 ½ miles. BLUE=Amicia Walk, 3 miles

The semi-octagonal Ox Yard is enclosed by sheds

that were constructed during the 1790s. Today’s outdoor Café stands where the “Dung Yard” once was…home to the Abbey’s 22 oxen.

The cluster of ancient buildings which form the Abbey are nestled into the valley of the River Tay; one feels utterly cushioned in the bosom of the land…it’s hard to remember that an ocean churns nearby, only nine miles to the south. But this very proximity to the sea is what made the Abbey such an appealing

home, for two of Devon’s most famous seafarers.

In 1545, the second Sir Richard Grenville, while still an infant (the first Sir Richard, his father, had purchased the Abbey from Henry VIII in 1541), inherited the Abbey. Richard Two became a career soldier and sailor who dreamed of colonizing the Americas, but, without royal patronage, his schemes came to nothing. In 1580, bitter about his failure to gain Royal sponsorship (which should have led to the Greatness and Fame that Richard desperately craved), Grenville sold the property to a more successful adventurer, Sir Francis Drake, who had just achieved the distinction of being the first Englishman to circumnavigate the globe (an endeavor which lasted from 1577 until 1580).

As my companions and I explored the Abbey, I became so enthralled by the architecture and by the gardens that I failed to carefully read The National Trust’s guidebook about the property; burying my nose in reference materials is something I always do…but later, after the day’s touring is done.

As I entered the Abbey, I thought: Home of Francis Drake? Well…that’s interesting.

But, had I then paid closer attention to the Trust’s Guidebook, I would have tumbled to the fact that the Abbey was also home to Sir Richard Grenville, who eventually became Vice Admiral of England’s fleet, and thus the hero of Alfred, Lord Tennyson’s poem THE REVENGE: A BALLAD OF THE FLEET .

Had I done my homework that day, right there, right then, scraps of verse would have been dislodged, off from dusty shelves at the back of my brain:

“At Flores in the Azores Sir Richard Grenville lay,

And a pinnace, like a flutter’d bird, came flying from far away.

‘Spanish ships of war at sea! We have sighted fifty three!’

….He had only a hundred seamen to work the ship and fight,

And he sail’d away from Flores till the Spaniard came in sight,

With his huge sea-castles heaving upon the weather bow.

‘Shall we fight or shall we fly?

Good Sir Richard, tell us now,

For to fight is but to die!

There’ll be little of us left by the time this sun be set.’

And Sir Richard said again: ‘We be all good English men,

Let us bang these dogs of Seville, the children of the devil,

For I never turned my back on Don or devil yet.’

Sir Richard spoke and he laugh’d, and we roar’d a hurrah , and so

The little ‘Revenge’ ran on, sheer into the heart of the foe.

With her hundred fighters on deck, and her ninety sick below;

For half of their fleet to the right and half to the left were seen,

And the little ‘Revenge’ ran on thro’ the long sea-lane between.”

“…And the night went down, and the sun smiled out from over the summer sea,

And the Spanish fleet with broken sides lay around us all in a ring:

But they dared not touch us again, for they fear’d that we still could sting.

So they watch’d what the end would be,

And we had not fought them in vain,

But in perilous plight were we,

Seeing forty of our poor hundred were slain,

And half of the rest of us maim’d for life

In the crash of the cannonades and the desperate strife;

And the sick men down in the hold were most of them stark and cold,

And the pikes were all broken or bent, and the powder was all of it spent;

And the masts and the rigging were lying over the side;

But Sir Richard cried in his English pride,

‘We have fought such a fight for a day and a night

As may never be fought again!

We have won great glory, my men!

And a day less or more

At sea or ashore,

We die – does it matter when?

Sink me the ship, Master Gunner – sink her, split her in twain!

Fall into the hands of God, not into the hands of Spain ! ‘ …. ”

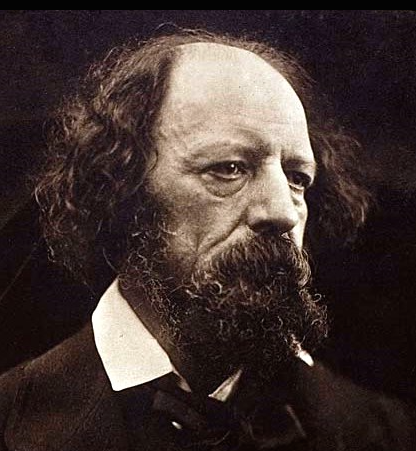

With his poem about the ship ‘Revenge,’ Alfred, Lord Tennyson…

Alfred, Lord Tennyson (born 1809, died 1892). Poet Laureate of Great Britain during much of Queen Victoria’s reign.

…bestowed upon Sir Richard the immortality that Grenville had sought. Of course, with his 14 stanzas Tennyson also dished up a prime cut of adrenaline-boosting, chest-pounding, revisionist history, nationalist propaganda and sheer poppycock! But what memorable Poppycock! Such is the Power of Rhythm and Rhyme.

Poetry seminar over, we’ll take a fast look inside the Abbey:

From the get-go, the Cistercian Abbey of St. Mary and St. Benedict at Buckland was a very well funded operation.

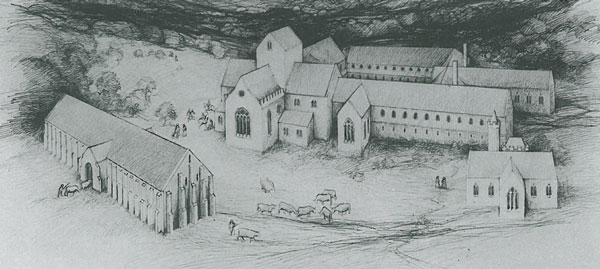

Reconstruction of how the Abbey might have looked shortly after it was built in the late 13th century. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

The Abbey was founded by Amicia de Redvers, matriarch of a boundlessly-wealthy Devon family. As you can see from the previous drawing, the Abbey in its original form, along with its Great Barn, was expansive and anything but humble.

We enter the Abbey through a short projecting wing that was built in the 1800s to contain a new staircase. The Tower was once at the cross-point of a larger structure. The roofline of the demolished south transept is still visible on the Tower’s exterior…just to the right of the FALSE flying buttress. The buttress is actually a chimney flue!

To the east of the front entry is the kitchen wing, which was added by Grenville, and then expanded in the 18th century. Per The National Trust: “This wing still reveals the retaining arches of the chapels that once issued from the east wall of the south transept at ground-floor level.”

Upstairs, in the Drake Chamber: A Ship Model. Nothing in this space is original to the time when Drake made the Abbey his home.

The beautiful ceiling in the Drake Chamber was installed in 1988. The hand-modeled frieze is done in a traditional, Devon style.

A window by a landing on the front stairs has been etched to commemorate the 400th anniversary of the Spanish Armada.

Inside the Abbey (which over the course of 700 years has been added to, remodeled, and sometimes deconstructed)

the collision of eras and architectural styles is most evident upstairs, where the traceried arch in the Lifetimes Gallery once formed part of an outside window looking out over the abbey chancel.

The Kitchen is in the

Abbey’s east wing, and was built by Sir Richard Grenville

to absorb the monastic chancel. Two open Hearths dominate the room.

The second of the massive Hearths in the Kitchen.

The antlers above the south Hearth are (fancifully) said to belong to a stag who once chased Sir Francis Drake up a tree.

Per The National Trust: “The Great Hall is positioned within the original crossing area of the church, directly beneath the tower and adjacent to the south transept that was demolished [in 1576] by Grenville to bring light to this, the most lavishly-remodeled room in the Abbey.”

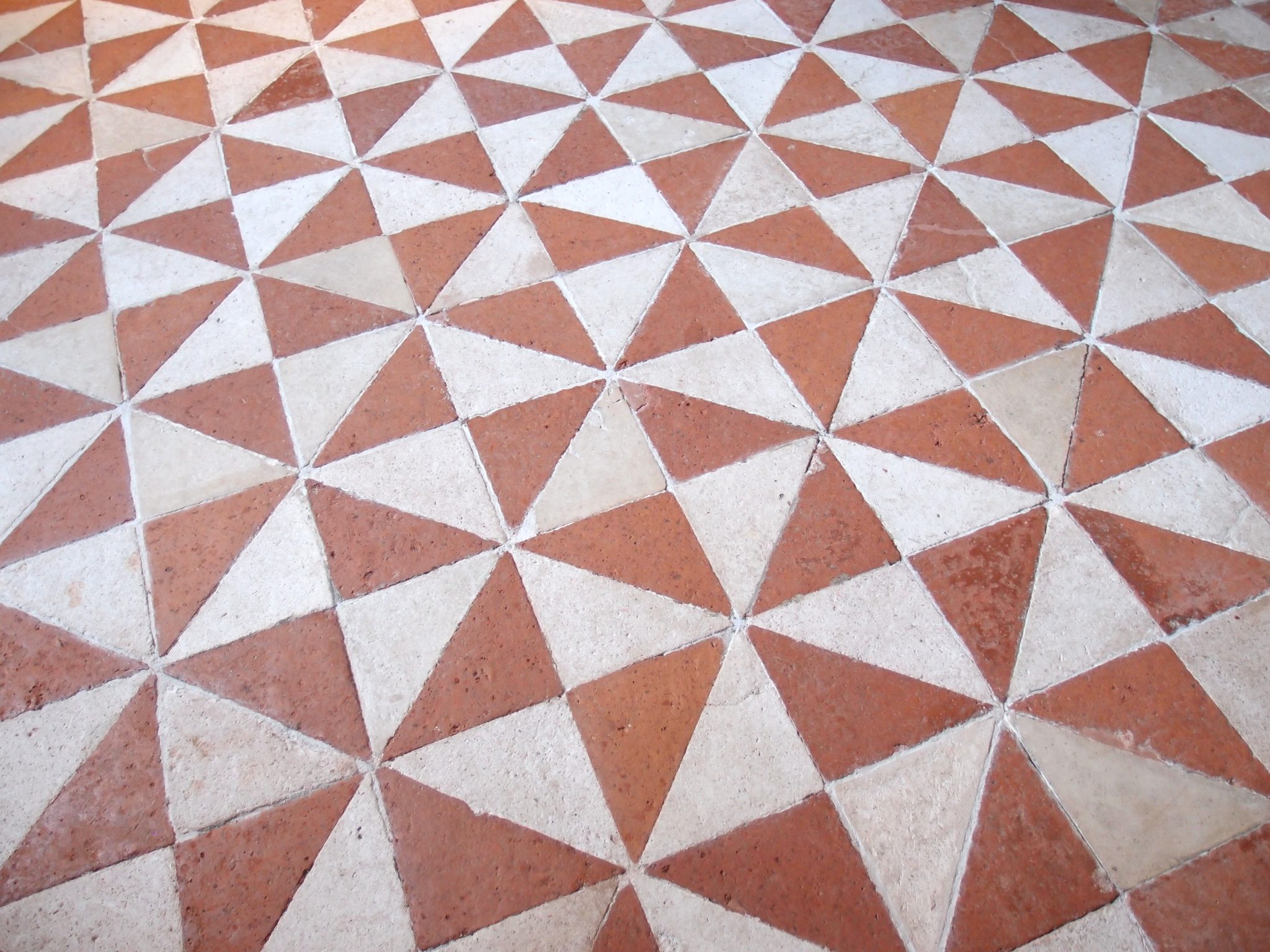

Every square inch of the Great Hall is decorated: from the plaster ceiling, right down to the stone-tiled floor.

The Great Hall’s upper walls are embellished with allegorical scenes. These plasterwork decorations have survived, exactly as they were, ever since Sir Richard Grenville’s occupancy of the Abbey.

The Great Hall’s granite fireplace, with herringbone pattern of slate at the back, is typical of the 16th century.

I very much enjoyed wandering through the architectural hodge-podge of rooms inside the Abbey itself, but the most magnificent structure within Buckland’s complex of buildings is certainly the Great Barn, which was erected in 1300. From the outside, the Barn, with its progressions of buttresses and arches, is striking.

But, from within, the Great Barn presents one of the most impressive volumes of space I’ve ever inhabited. The Barn’s interior is far more inspiring than most of the ecclesiastical buildings I’ve visited.

My view, looking toward the south end of the Great Barn. The walls date from 1300, and the arch-braced wooden roof was constructed in the 15th century.

Continuing with The National Trust’s description:

“The outstanding architectural feature of Buckland is the Great Barn. It was clearly planned for a prosperous community and belongs to the same period as the abbey church. Its dimensions seem to dwarf the church, and it is set obliquely only 24m from the chancel. The putlog holes where the medieval scaffolding was inserted are still open, and dovecotes remain above the great medieval doorways.” The barn would have been used for storage: of harvested crops, and for wood and hides from the Abbey’s estates. The central space, at the crossing-point of the Barn’s wings, was kept clear, and used for winnowing.

Outside of the Great Barn, I found this superb Herb Garden. Remember, the walls which form the backdrop for this Garden were built in 1300. Walls of such antiquity are the

Ultimate Garden Ornament.

Per The National Trust: “ It is probable that the Herb Garden outside of the Great Barn was established after a visit by Vita Sackville-West. The irregular-shaped beds contain over 40 different herbs.”

[ Note: For a good look at Vita-Sackville West’s own gardens at Sissinghurst, read my Armchair Diary titled

PART THREE. RAMBLING THROUGH THE GARDENS & ESTATES OF KENT, ENGLAND. ]

We headed toward the northern-most portions of the Abbey’s Gardens. The grounds immediately surrounding the Barn and Abbey are all 20th-century creations… but creations which are seamlessly integrated into ancient settings. This merging of the modern and the antique is something at which British gardeners excel.

Our first stop: the “Elizabethan Garden,” which was designed during the 1990s in a Tudor style.

Armillary in the forecourt of the Elizabethan Garden, with the north end of the Great Barn looming behind.

The central path in the Elizabethan Garden.

At center, rear: The Abbey’s Tower (which was originally located at the center of a larger building), with its undulating battlements (these decorative flourishes were added in the 18th century).

In search of the Kitchen Garden, we follow this alleyway, which runs outside the northern wall of the Elizabethan Garden. These walls are ancient farmyard enclosures, and have been used to define newly-made gardens.

The eastern-most sections of the Cider House Garden abut the Cider House Bed & Breakfast building (shown here)….looks like QUITE a nice place to bunk, eh?

The private terrace of the Cider House’s Bed & Breakfast accommodation. More and more of The National Trust’s properties are offering B&B lodgings (earlier in this Diary, I forgot to mention that a B&B is also on site, at Agatha Christie’s Greenway).

We’re now within the public section of the Cider House Garden, with wonderful views of the Estate’s hillsides, where flocks of sheep graze.

Our visit to Buckland’s gardens nearly complete, we leave the Wild Garden, and head back across the Central Lawn of the Cider House Garden.

Just past the eastern gate to the Cider House Garden, we came upon this beautiful but slightly disturbing bench. (Horses’ heads immediately lead to thoughts of that grisly scene in GODFATHER ONE.)

Having enjoyed this final look at the Abbot’s Tower, we decided that our Scones-and-Tea-Time was LONG overdue, and so repaired to the Ox Yard Cafe.

Back at the Car Park, I decided that, at some point in the future, I must return to Buckland Abbey: there are still Estate Walks to explore. (Note: the shaded gray area on the Visitors’ Map indicates the Bed & Breakfast area of the Cider House Garden.)

Having hatched plans to meet Janet and Barry later for dinner back in Dartmouth, Anne and David and I took our leave from Buckland Abbey.

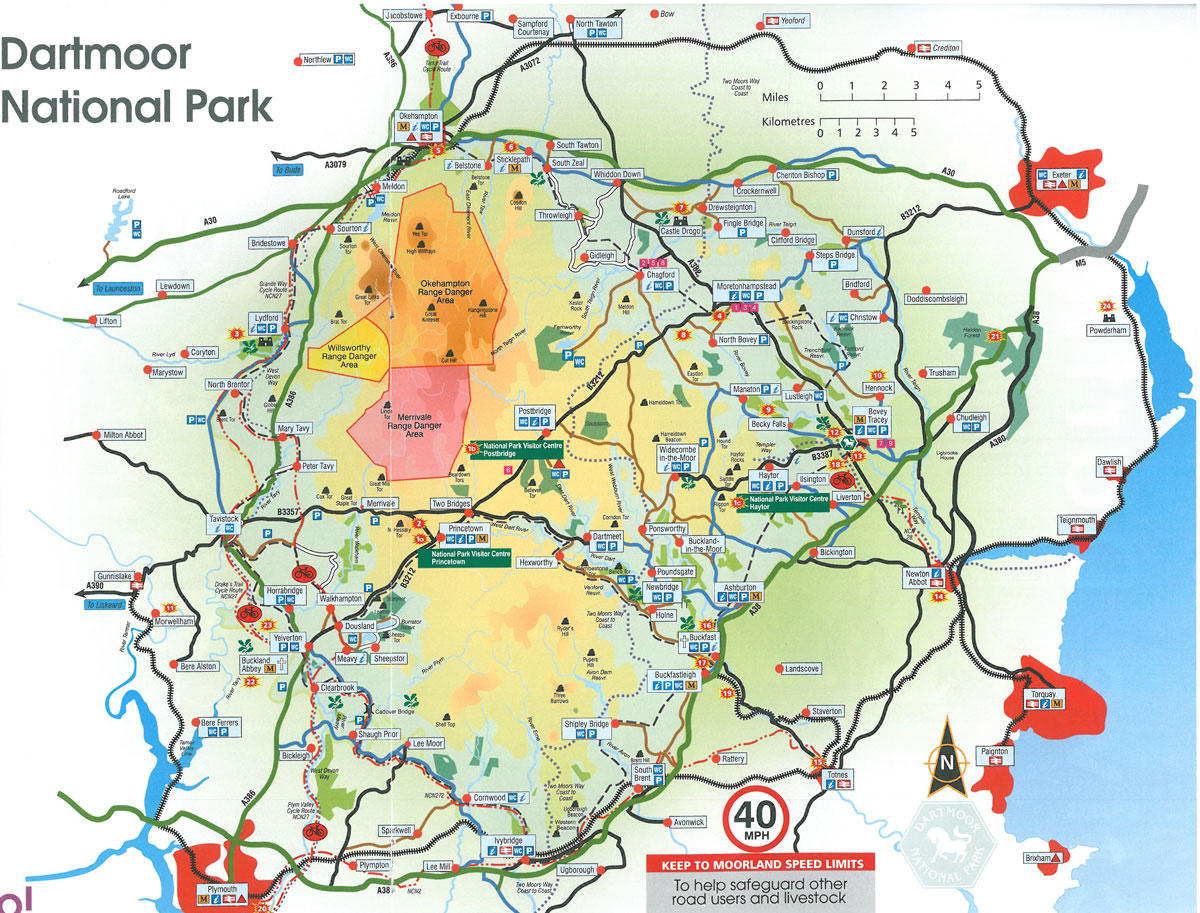

Anne decided that our homeward travels should be along more scenic routes than those of our utilitarian, morning commute. And so Anne’s chosen path led us from west to east, and across the otherworldly landscapes of Devon’s Dartmoor National Park.

Apart from knowing that Sir Arthur Conan Doyle set his novel THE HOUND OF THE BASKERVILLES amid the mist-shrouded peat bogs of Devon, I’d given little thought to the existence of Dartmoor.

But my too-brief visit there, in late afternoon of June 29th, made an indelible impression . Visions of Dartmoor’s intricate folds in the land; of stark pyramids of hundreds of rocky tors; of wild horses grazing; of free-roaming cows wallowing in ponds; and of still more cattle lounging proprietarily on the warm pavements of the narrow roadways; of the depressing, Victorian hulk of Princetown’s high security prison; of hilltops which made me feel as if I had ascended into the sky…these images now enrich me. Rarely have I been enveloped by such clarity of light, or have I been in a place that seemed simultaneously so joyful, and yet so forlorn.

A quarter of the way into the Park, we stopped near Walkhampton, at a car park on Route B3212.

Bicyclists, Cattle and Motorists congregate by Route B3212, on one of south Dartmoor’s higher peaks.

Clearly Contended Cows, with a Tor on the horizon. “Tor” is an old English term, probably Celtic in origin. A Tor is a pile of bare rocks, at the peak of a hill.

A Mother and her Colt: utterly indifferent to my presence. These animals know that this land belongs to them.

The more I see of the World, the more the disparate threads of my hundreds of preoccupations — preoccupations which I’ve accumulated over many decades — seem to intertwine into something resembling a Sensible Whole, one which makes me suspect that there might indeed be an Actual Narrative to my Life.

In Southern Devon, especially, Landscape and Warfare and History and Mysteries and Myth, along with Gardens and Architecture and Livestock and Poetry and Art: these all presented themselves to me as indispensible parts of an enormously rich Whole, and a Whole which resonated with me on the deepest, personal levels.

I constantly yearn to revisit all of the marvels that I’ve been fortunate enough to see. But my thoughts about Southern Devon have become more than mere longing: I now think of the place with love.

Part Two of my Travel Diary about Southern Devon will appear, in time…

Copyright 2015. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

7 Responses to A Well-Spent Week in Southern Devon, England. Part One.