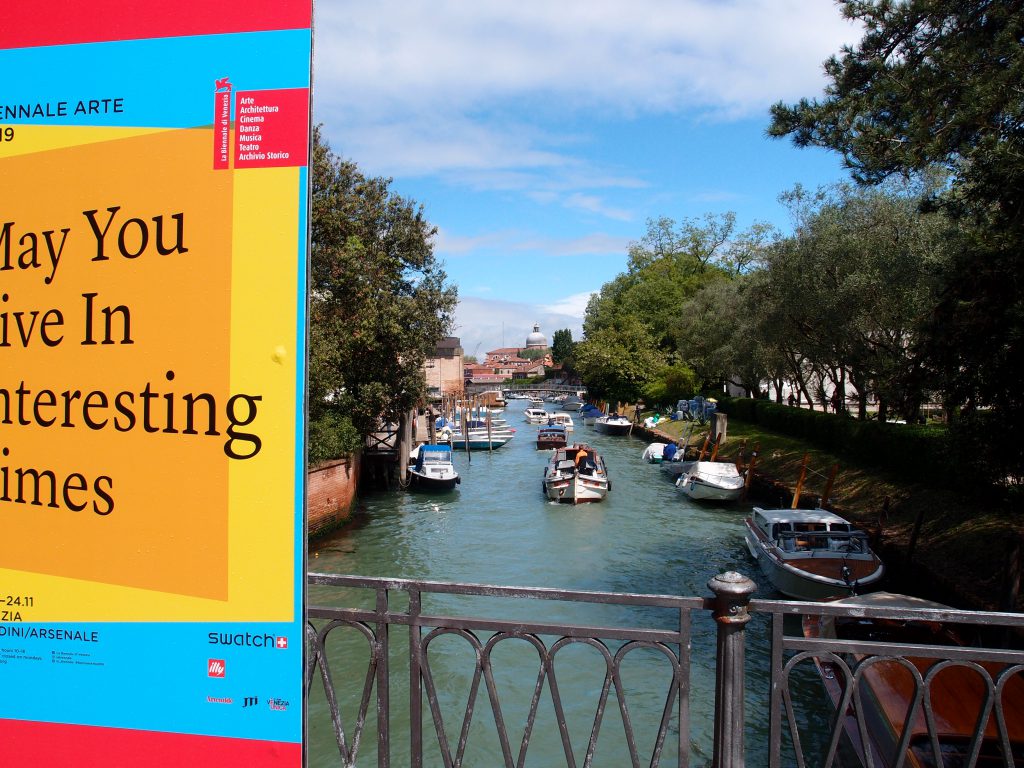

We’re at the eastern end of the Castello district of Venice, on the Riva dei Partigiani. This billboard directs us to the Giardini section of MAY YOU LIVE IN INTERESTING TIMES: Venice’s 2019 Biennale Art Show. The Biennale was established in 1895, & every two years the Giardini and Arsenale sections of Castello become THE premiere international showgrounds for contemporary art.

When it comes to La Biennale, years and fashions pass, but little of its Essence changes, despite various Curators’ declarations that: “THIS Biennale shall be precedent-shattering!” In May of 2011 I attended Biennale‘s Press Days, and later reported about that event for New York Social Diary. In May of 2019 I was once again privileged to be invited to attend Press Days; this time as Publisher of my own Diaries for Armchair Travelers.

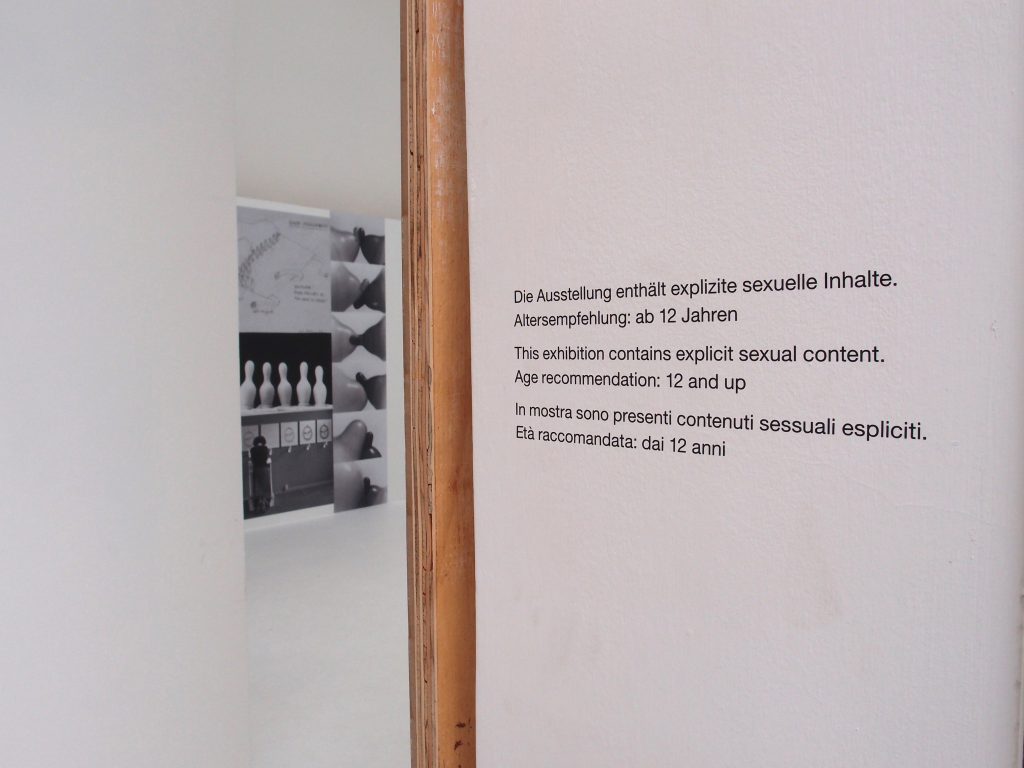

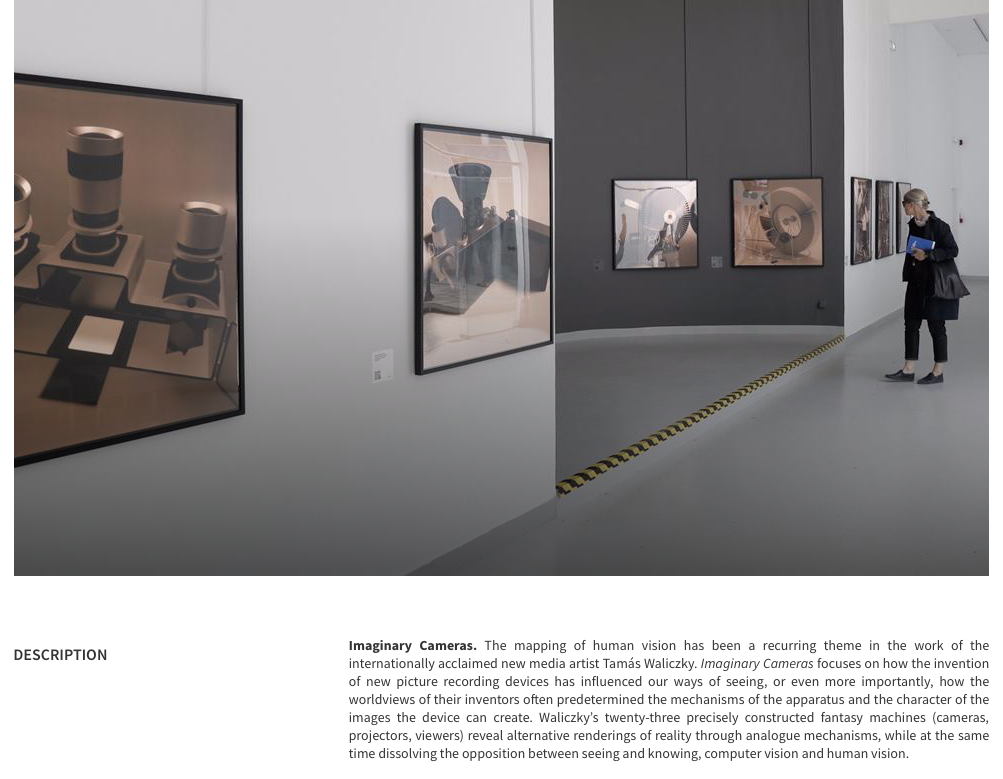

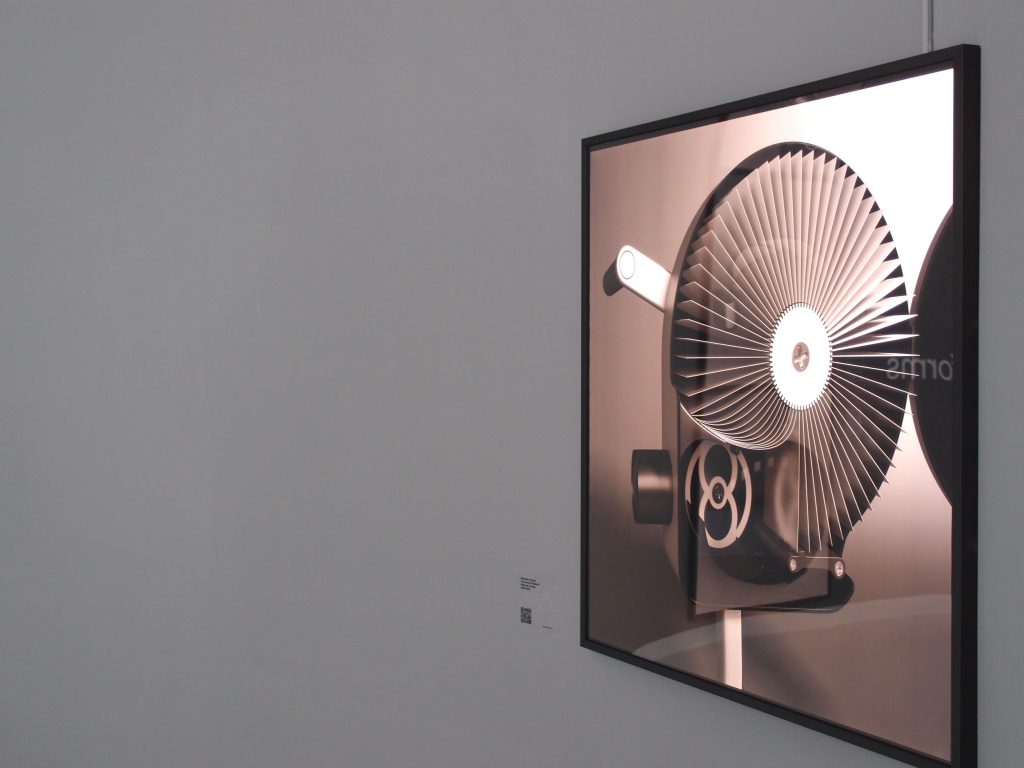

I shrugged and then smiled as I reviewed what I’d written 8 years ago: “La Biennale is the contemporary equivalent of the Chelsea Flower Show, both in size and renown. But where Chelsea is well-mannered, Biennale is In-Your-Face. Politics! Noise! Profanity! Nudity! (I’ve left out my photos of the profane.) The art on display ranges from nonsensical to sublime. Bombastic political commentaries are cheek to jowl with exquisitely made paintings and sculptures. Geniuses and charlatans abound; it’s hard to tell them apart. Marketing types eye gallery directors and journalists; there are reputations and, ultimately, dollars to be made.”

And so, WHY report now about yet another Biennale? The answer is easy: with each new Biennale, a Visitor’s opportunities for discovering the World’s artists expand … even though the creations that are displayed in Venice have been chosen by a Curator who has been appointed aesthetic gate-keeper for this year’s participating Artists. [Note: The issue of whether a single, powerful, different Curator should be at the helm of each new Biennale is a Whole Other Subject; one which I’ll not attempt to tackle here.]

Ralph Rugoff. Curator of the 2019 Biennale

The long-form style of my DIARIES FOR ARMCHAIR TRAVELERS allows me to share with

you the overwhelming, thrilling, TOO-muchness of La Biennale. I want to provide you with an accurate impression of what my total immersion into Biennale’s displays was like. Where other journalists feature their Top Ten Pavilions, I will, in Two Long Parts (Giardini exhibits first, Arsenale exhibits second) present the Show Grounds in the exact sequence as I discovered them. While I won’t be shy about identifying MY favorites, I’ll reveal the greater part of what I saw. From my mountain of photos you’ll be able to draw your own, critical conclusions. But, in the end, formulating critiques isn’t important. Instead, as you study the fullness of my photographic record of the 2019 Biennale, I hope you’ll sense that BEING at and RESPONDING to La Biennale is a largely sensory experience: exciting, irritating, inspiring, exhausting, surprising, addictive, energizing, and unforgettable.

Before we jump with both boots into La Biennale (and on many occasions during my recent

8-day stay in Venice, BOOTS were necessary), a bit of context:

In the foreground: Aerial View of the Punta della Dogana, on Dorsoduro. Dorsoduro is one of Venice’s 6 sestieri. The imposing white, domed building which faces the Grand Canal is the Basilica of Santa Maria della Salute. The Salute Vaporetto landing

(a stop on the ACTV public water bus network) on the Grand Canal is adjacent to the Basilica. Diagonally and to the right, across the Grand Canal: we see Piazza San Marco, the Campanile, the Basilica of San Marco, and the Palazzo Ducale (Doge’s Palace).

The wide channel of water along the lower edge of this photo is the Giudecca Canal. The Centurion Palace Hotel is the 2nd large complex of structures to the left of Salute, and its

entry courtyard is visible in this photo. Image courtesy of Francois Pinault Foundation.

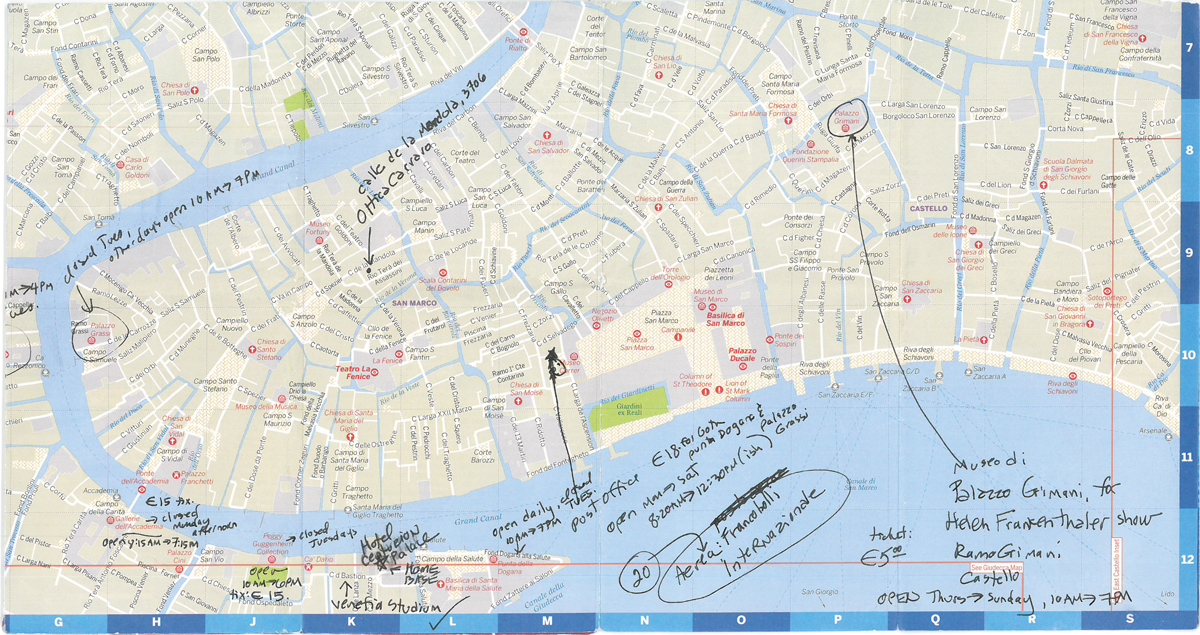

I’m a Travel-Dinosaur: NO cell phone, NO GPS…I carry only a tattered and well-annotated paper map.

On May 8, 2019, after a long day of travel—which had commenced in Tunbridge Wells, Kent; proceeded with an interminable taxi ride along traffic-clogged motorways to Gatwick Airport ( on England’s southeastern coast ); continued with a zippy 1-hour-45-minute British Airways flight to a fogged-in Marco Polo Airport in Venice; and concluded with a 2-hour boat ride on the Alilaguna water bus through driving rain and across worrisomely-storm-tossed waters to Piazza San Marco— I was relieved to finally arrive the Centurion Palace Hotel, which is my home away from home, whenever I’m in Venice.

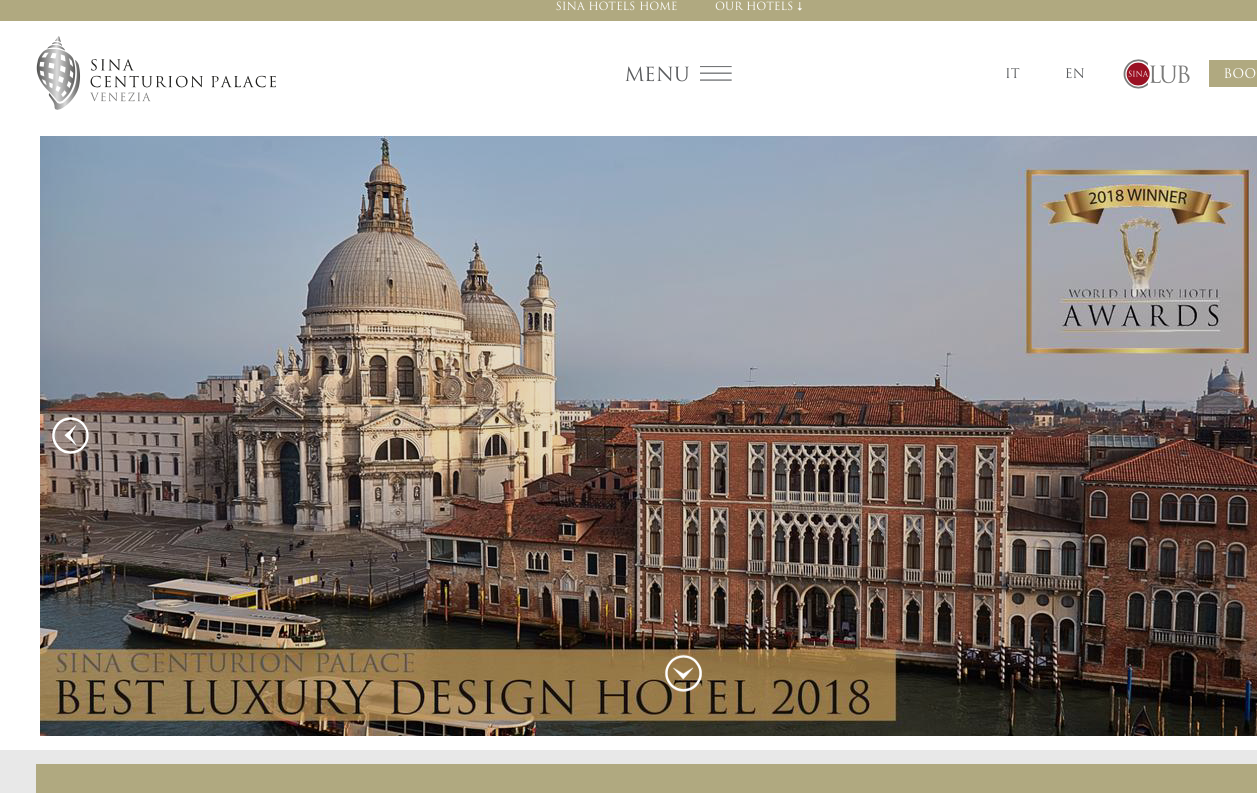

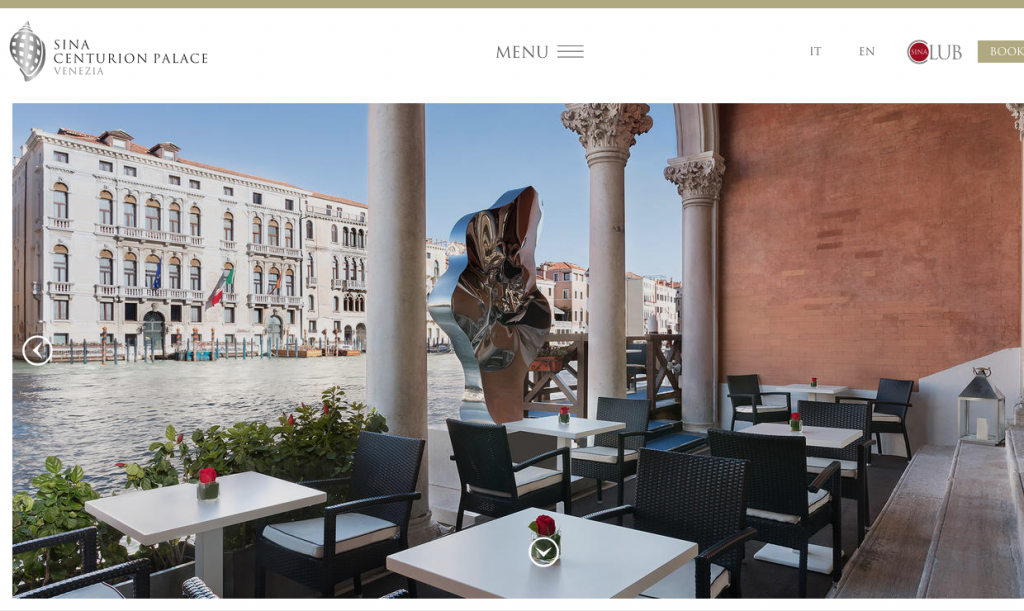

Screen shot of the Centurion Palace Hotel’s website.

The Centurion Palace occupies a prime position on the Grand Canal, but its location in Venice’s less-visited Dorsoduro section—which is across the Canal from the

tourist-clogged alleyways and waterfronts of San Marco—allows its Hotel Guests to enjoy extreme tranquility…a state of being which is getting harder and harder to come by, in Venice. Image courtesy of the Centurion Palace Hotel.

https://www.sinahotels.com/en/h/sina-centurion-palace-venice/

During most of my traveling hours that day, I’d moved forward with my usual, philosophical calm. En route, I surrender to the Gods of Transit: not much upsets me. But during those final 2 hours, as my Alilaguna water bus voyaged across the 11 miles of Lagoon and Basin which separate Marco Polo from Venice, I’d begun to lose my travel-cool.

![]()

At 6PM, when the Alilaguna boat left the Airport dock, intense, December-cold rain had already darkened the skies; it seemed nighttime would arrive several hours early. As we sailed east, along the channel in the Lagoon which leads out to Venice and ultimately to the Adriatic Sea, choppy waves began to slap against the boat. Unable to stray from the narrow course of his travel-channel, the pilot continued straight ahead, while uneven swells clobbered the long sides of our vessel. Luggage tipped down stairs and careened across the aisle: passengers’ chatterings became muted. As thick fog roiled outside, the boat’s windows became opaque with condensation. Every 10 minutes, our captain idled his engines, and instructed his assistant (who, his feet on the dashboard, contentedly studied a magazine) to grab a mop with a rag knotted around its business-end. The be-mopped assistant would then step outside, and carefully inch his way across the wet prow until he reached the outer surface of the bridge’s windshield. He’d wipe thick mist off of the glass until the pilot inside tapped on the window to indicate “I can SEE again,” and then the assistant would calmly slide back inside to the bridge, where he’d resume his reading. Each time the boat’s engines idled, the heavy, vaguely sickening smell of diesel fuel within the passengers’ cabin intensified.

But our captain knew how to handle his boat, despite the vagaries of Venetian weather.

Accelerate. Idle. Wipe. Accelerate. Idle. Wipe. Repeat as needed.

And so, with few visible clues regarding our boat’s whereabouts, and as the waters became increasingly Oceanic—literally storm-tossed, while rain lashed down and gray-black thunderheads billowed overhead— the pilot managed to lurch us from

one dock to the next: first to Murano, then to Fondamenta Nuove, and to Ospedale,

and to Lido, and to Arsenale, and finally to San Marco, where I disembarked, and then walked (rather, slogged…so driving was the rain upon the pavements) to another dock where I waited for a Vaporetto to take me across the Grand Canal, to Dorsoduro. As I stood in a long queue, watching for that 2nd water bus, I realized I’d become thoroughly soaked, all the way through my layers of sensible clothing and right down to my clammy skin. But suddenly, the rain stopped. I looked behind me and saw that a gentleman had silently held

his large umbrella high, to shield us both. Humans can be so sensible and kind, sometimes.

Weary & bedraggled, I finally arrived at the Centurion Palace Hotel.

Inside of this historic palazzo (with 50 Guest-rooms, all of them unique) the décor is both comfy and ultra modern: a perfect mix of antique and contemporary. The people who work here are all superbly skilled, relaxed, businesslike and welcoming. To secure accommodations for myself during the Press Days of Biennale 2019 (when every good hotel room in Venice would be booked) I’d planned FAR in advance: by February of 2018, I’d already corresponded directly with the Hotel about my reservation.

And, in the time leading up to my stay at the Centurion Palace, I’d received invaluable

assistance from Mr. Emanuele Vio, the Head Concierge, who effortlessly overcame

some longstanding bureaucratic snafus I’d had with the Biennale’s back office. Mr. Vio also arranged for the excellent chauffeur services

of Mr.Aldo Dorre:

following my time at Biennale, Mr.Dorre took me on two long, mainland day-trips, as I explored several grand Baroque gardens , and 3 of Palladio’s villas. On the eve of my first day of these long-planned visits to Veneto estates, Mr.Vio told me he was concerned about the weather being awful; that Venetians were calling the recent, weirdly cold, hurricane-like conditions “May-Cember” (for May-acting-like-December). I assured him that, during my years as a garden-photographer, I’d never met a rainstorm nasty enough to keep me indoors. Indeed, on the most turbulent-weather-days, some of the Hotel’s staff kept discreet watch for the return of this American Lady (unglamorously outfitted in a Wintertime-combination of cargo pants, turtleneck, waterproof boots, waxed rain jacket, bucket hat & silk gloves) who’d ventured out to do her work, festooned with cameras, and grinning in defiance of the storms.

[Note: There’s No Quid Pro Quo, when I say nice things about hotels and other

service-providers! I pay list price for everything, and report candidly, wherever I find

extraordinary people and places.]

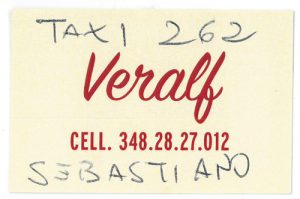

To book Mr.Dorre for travels throughout the Veneto mainland, call Sebastiano. Tell him you’ve been referred by “Signora Nan,” who stays at the Centurion

Palace Hotel.

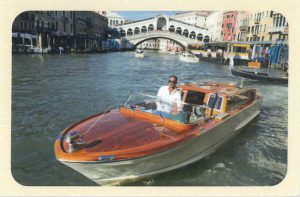

Also book Veralf for all water taxi services, in Venice. Avoid a poky

Alilaguna voyage back to Marco Polo Airport, and instead treat yourself to a speedy water taxi

ride.

On Dorsoduro: the inland entry to the Centurion Palace Hotel. I took this photo later during my stay, on a rare, sunny afternoon.

The entry courtyard of the Centurion Palace Hotel

View of the Grand Canal, from the loggia of the Centurion Palace Hotel. Image courtesy of the Centurion Palace Hotel

Wonderfully, the Hotel staff tucked me back into the very same room that I’d so happily occupied during my last visit to Venice, in Sept of 2012: I’d been there to write about the Architecture portion of La Biennale, as well as the annual Regatta Storico (Historic Regatta, during which the Grand Canal is filled with a parade of ornately decorated barges and gondolas, and then capped off by gondola races).

I am a creature of Hotel-Habit, & following that tough day’s journey from England to Italy, I was glad on the night of May 8, 2019, to be returning to “MY” room at the Centurion Palace.

After a light room-service supper….

Salad, Fruit, Bread: my formula for late-night noshing. This is how I stay healthy, when I’m traveling for a month or longer.

… and a hot shower…

In my bathroom: all surfaces are either mirrored, or covered—wall, ceiling, and floor—in little squares of gilded Origami paper, with a clear plastic overcoating, for waterproof-ness. While showering, I stood in the cylindrical, glass shower stall, and looked through double-wide-windows, out across the Grand Canal. A totally bonkers setting: which transformed all of my ablutions into joyous and life-enhancing events.

…I collapsed into bed.

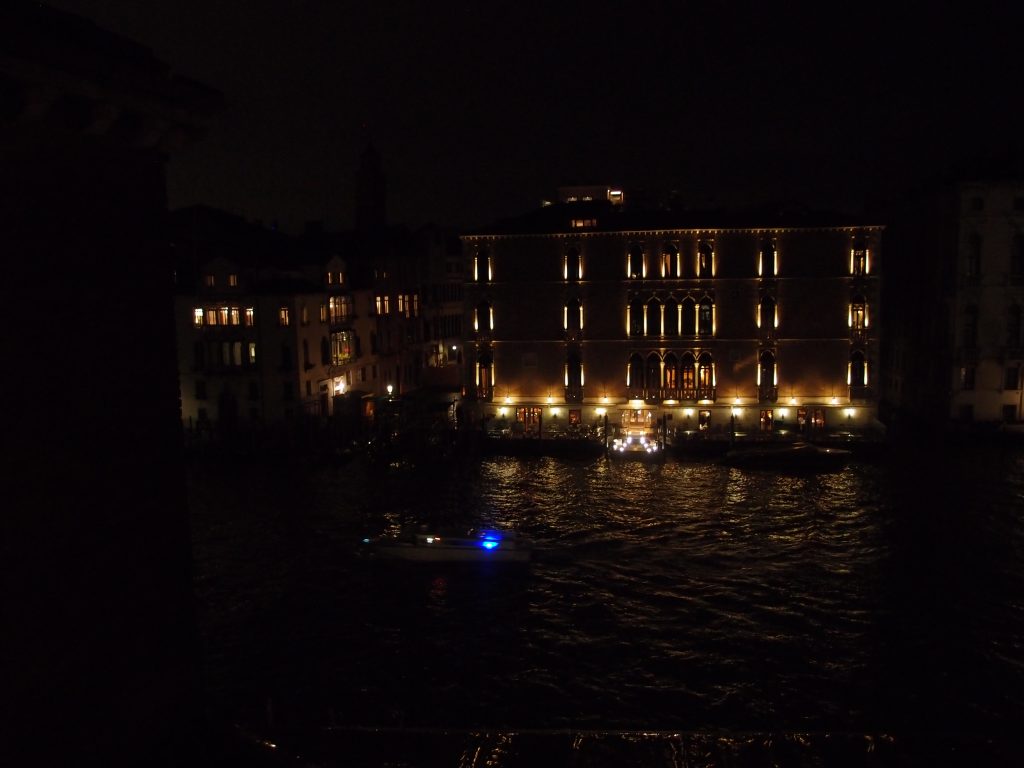

My last stormy-night view of the Grand Canal, before I crept under the bedcovers,

late on May 8th.

On NOT-stormy days, this was my early-morning view of the Grand Canal. Directly across is the Gritti Palace Hotel.

Hallway near to my Hotel room

View from that Hallway, down into entry courtyard of Hotel, on a sunny afternoon.

Early on the morning of May 9th, as I savored breakfast in the

soothing cocoon of the Hotel’s Restaurant…

Image Courtesy of Centurion Palace Hotel

….my mood soared, despite the steady rain outside. Today would be my

first of two Press Days: I would soon visit Biennale’s National Pavilions in the Giardini.

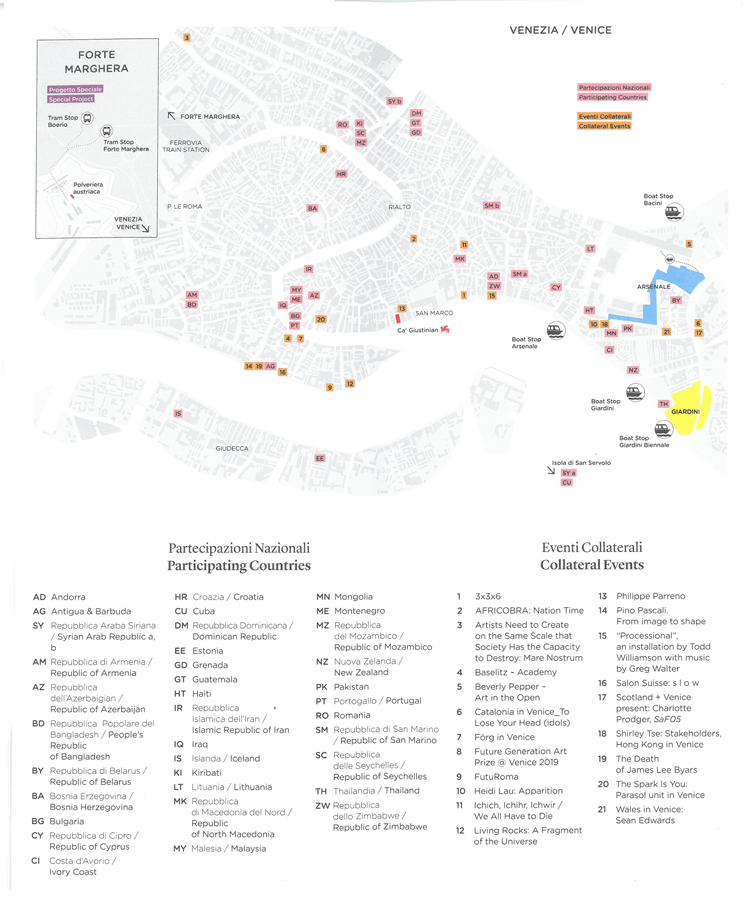

As mentioned, the principal venues for La Biennale are Giardini, and Arsenale.

But the capacity of these two settings is insufficient to contain all of the World’s

National Exhibits, along with many official Collateral Events.

Thus, grand palaces and cavernous warehouses throughout the entire city also are put to use as Biennale-galleries (which remain open to the Public for the entire run of the Show: from May 11th through November 24th,2019 ).

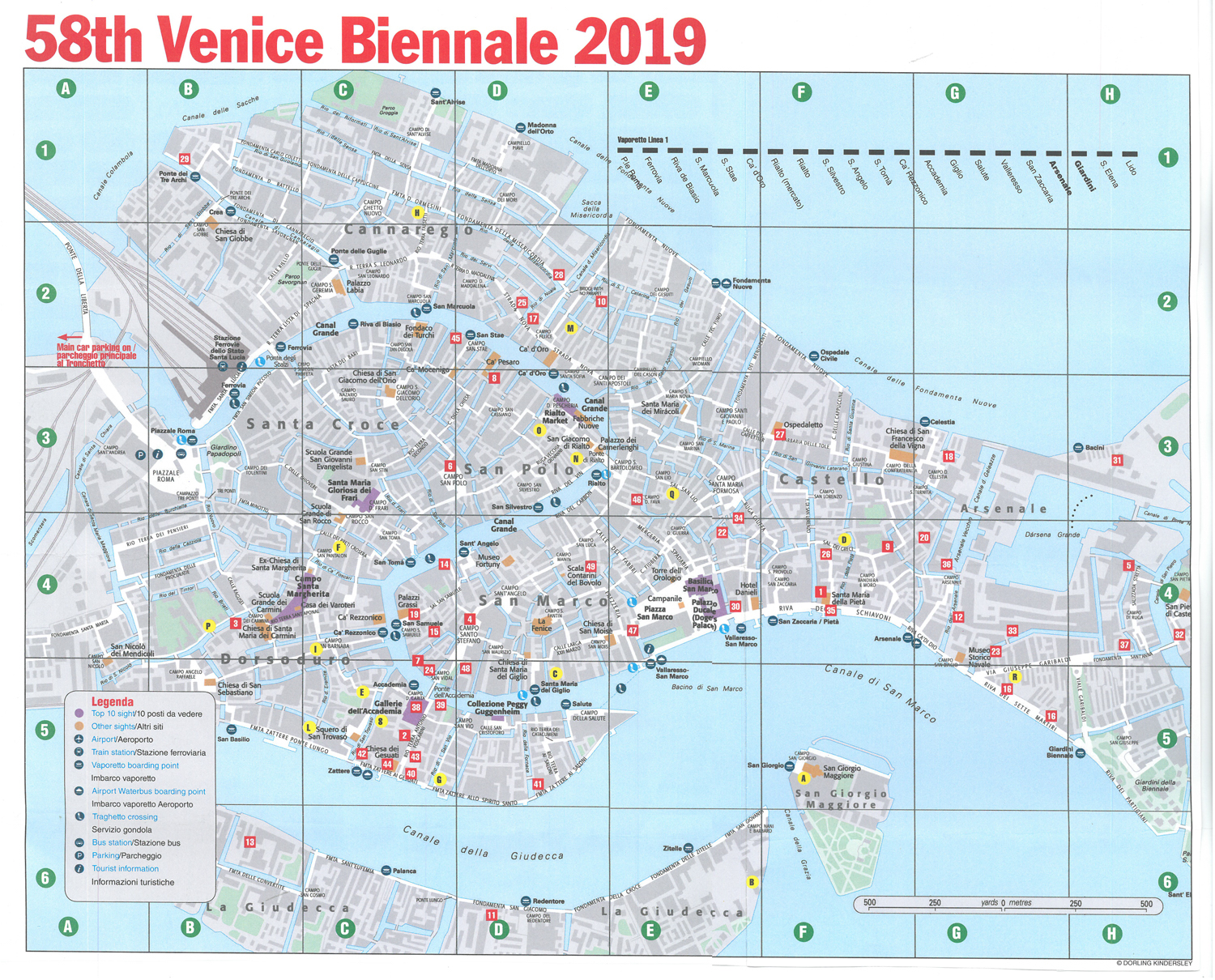

Map of all Biennale 2019 locations, throughout Venice.

Detailed Map of Biennale 2019 Offsite Locations

Collateral Events List

But First: An Essential Detour! After my two, long, Pre-Opening Press Days, I also made a point of visiting most of the offsite Biennale exhibits. Before I bombard you with photos from Day One of my Press Day explorations of the Giardini displays, I must highlight LIVING ROCKS—A FRAGMENT OF THE UNIVERSE, a spectacular Collateral Event, which is felicitously located in my very own Dorsoduro neighborhood, on Fondamenta Zattere ai Saloni.

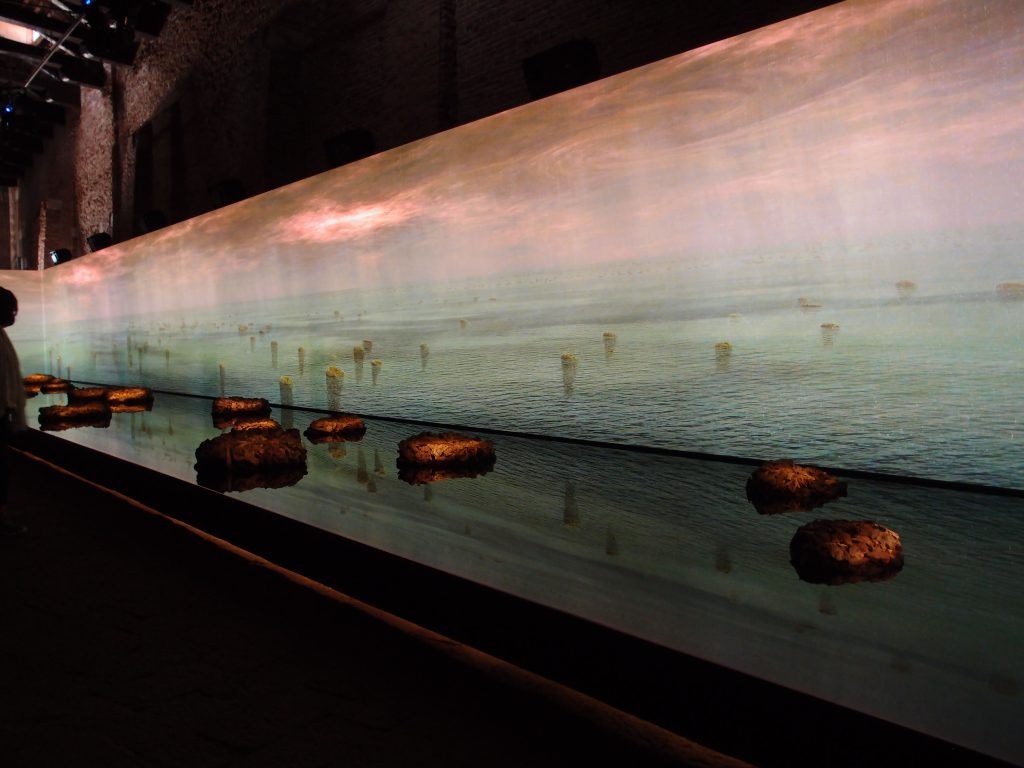

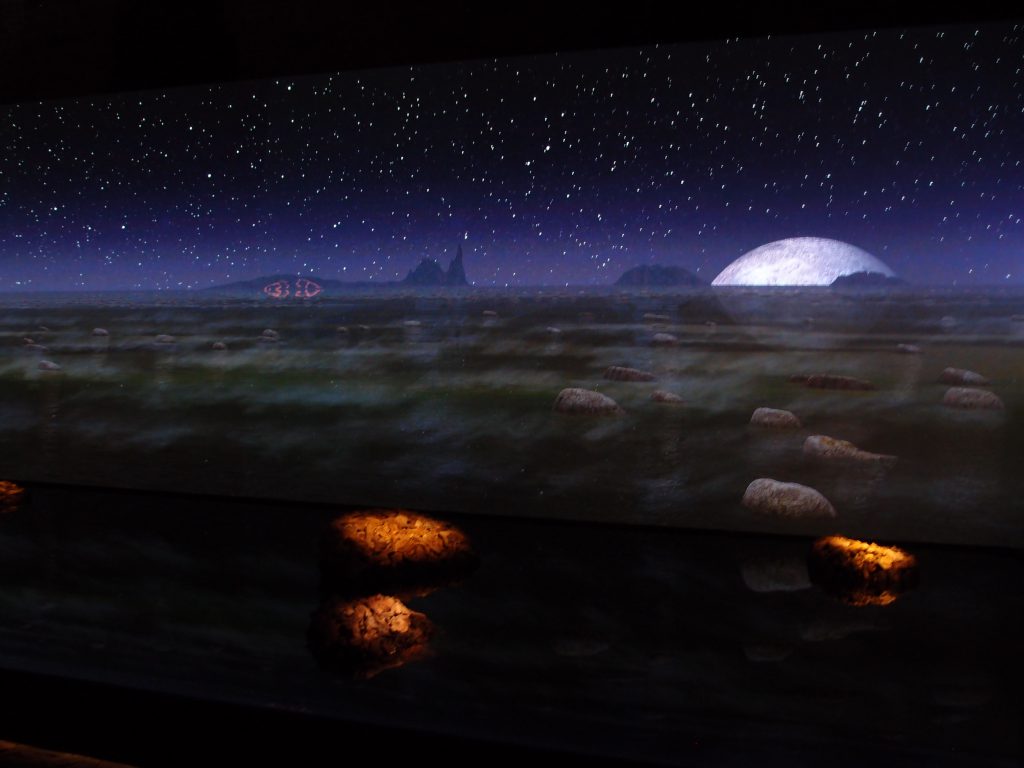

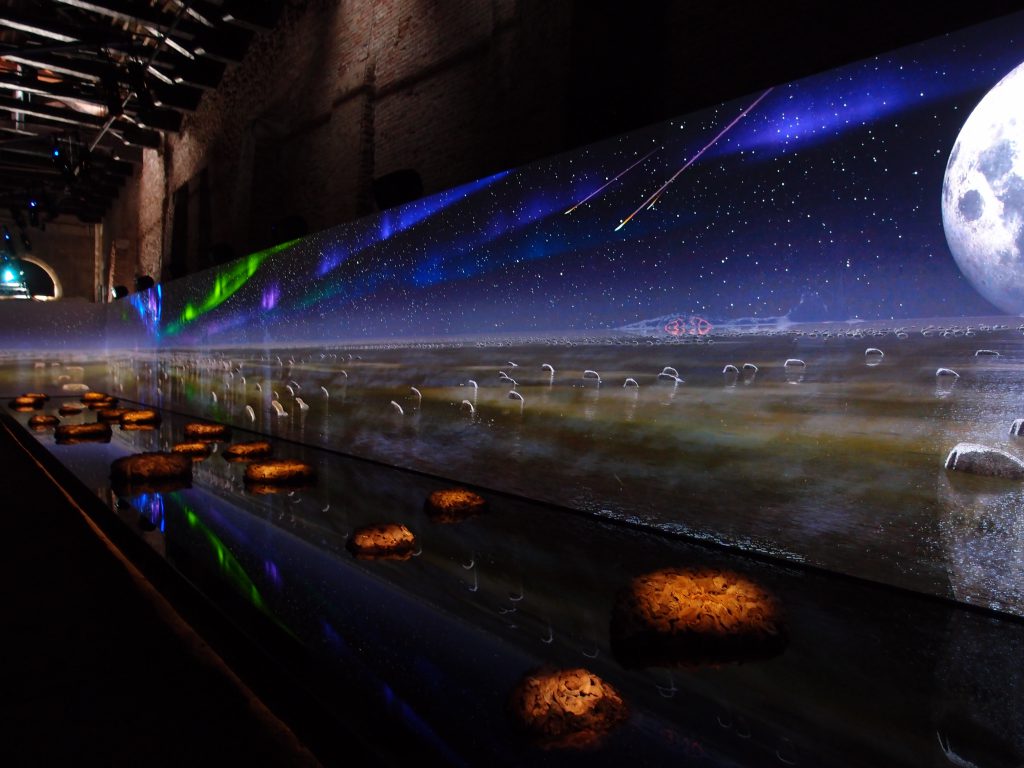

LIVING ROCKS is an astounding conceptual installation, orchestrated by

the Australian artists Lesley Forwood and James Darling. I made two separate visits to LIVING ROCKS: each time, I spent 30 minutes sitting in the darkness, awe-struck, as I immersed myself in the sounds and sights of this Show. For me, LIVING ROCKS is easily the most powerful, most beautiful, most technically-subtle and most thought-provoking of ALL of this year’s Biennale offerings. Words are insufficient, but I’ll sketch the scene:

*Next to the Giudecca Canal and set up in a dark, cavernous warehouse: a 30-meter-long pool, with rocks scattered across the water.

*On 3 sides of the pool: large screens onto which are projected constantly changing images of a barren seascape in Australia.

*In a repeating cycle of 20 minutes: images morph to reflect millions of years of planetary evolution, from primordial times to the present. Cataclysmic geological events, astronomical fireworks. Changing weather conditions, illuminated by the risings and settings of the sun and moon.

*No dinosaurs: the only living creatures appear at the end of the cycle, as flocks of birds swoop from one end of the projection screens to the other. As I watched the movements of these Virtual Birds, my skin tingled, and for a moment I felt the thrill of flying with them: it’s undeniable that the best art stimulates our bodies, as well as our eyes and our souls.

*The music that accompanies the light-show is an original composition, performed by the

Australian String Quartet. The soundtrack is simultaneously lyrical and muscular, and is accompanied by a rumbling undertone of body-vibrating noises.

Here’s a (regrettably static) sequential sampling of the images:

Living Rocks. We’re back outside, on the paved waterfront of Dorsoduro’s Zattere.

Directly opposite from the

Living Rocks exhibit, across the wide expanse of the Giudecca Canal, we see

Chiesa del Santissimo Redentore (aka Il Redentore), which was designed in 1592 by

Andrea Palladio.

NOW: re-energize yourself with some coffee. It’s finally time for our Giardini-Explorations.

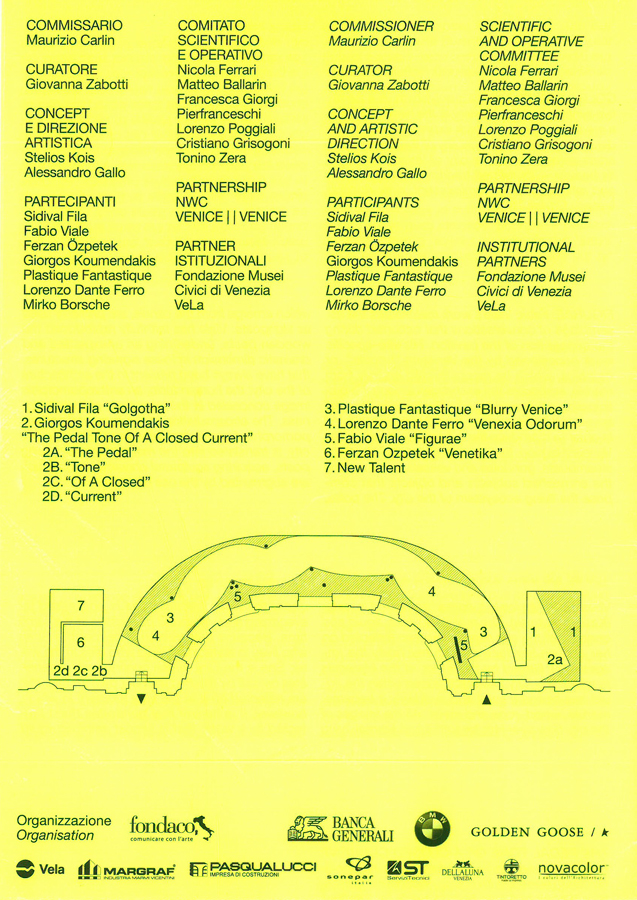

Cover of Pre-Opening Program Book, for Biennale Arte 2019.

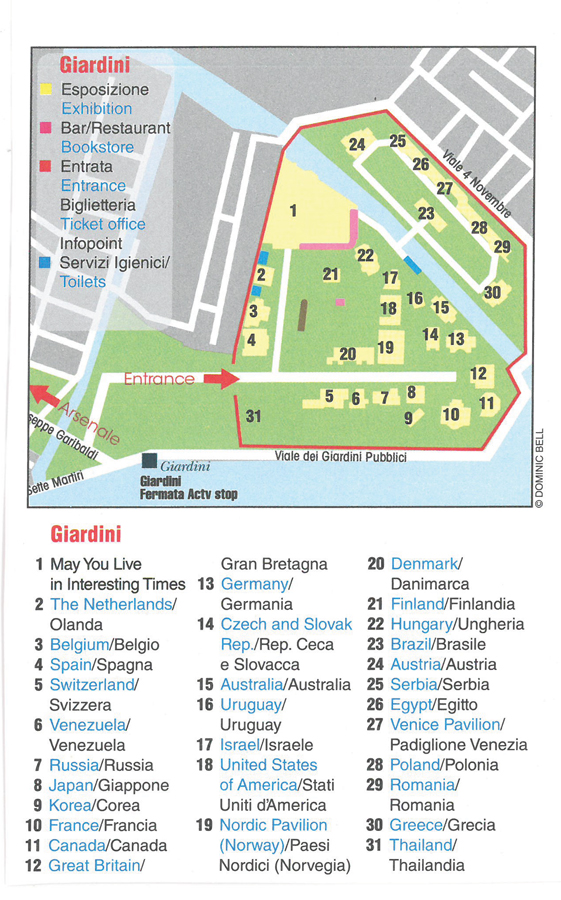

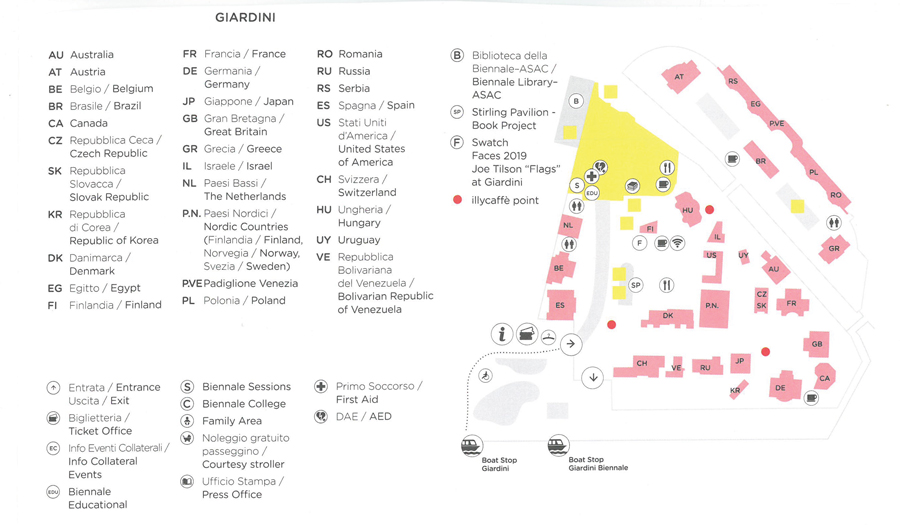

Giardini Exhibits Location Map

Giardini Pavilions–Detail Map

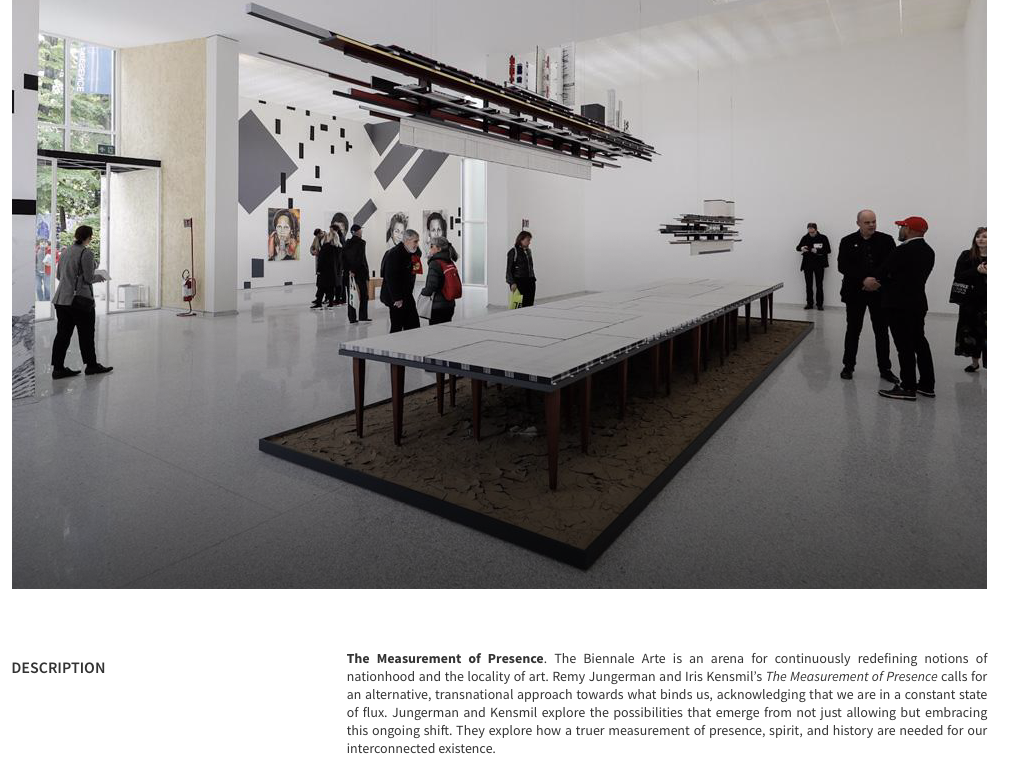

When it comes to international showcases for avant-garde trends in art, La Biennale perches on Top of the Prestige Pile: it’s often called “The Olympics of the Art World.” For the last several Shows ( all with a duration of 6 months ) , total attendance figures for each Event have numbered 500,000. The artists featured at Biennale have always been jury-selected, but prior to 1972 the Shows had no predetermined Theme. In 1972, Curators began to assign Themes to the Show. [Note: This initial Theme was “Work or Behaviour;” and WHAT could that have actually meant when it came right down to choosing which Artists should be included? But this theme-picking fetish seems to me to be mostly an attempt to give Biennale’s Marketing Department a Promotional-Hook: a Focus to make their jobs a little easier.]

The gardens (Giardini) which have become the Biennale’s permanent exhibition grounds

were created at the beginning of the 19th century at the behest of Napoleon Bonaparte when marshlands along the banks of the Basin of San Marco were drained

to make a public park.

From its earliest incarnation, the Show’s broadminded directors have included international artists. In 1895, the first Biennale attracted a whopping 224,000 visitors: clearly, those original curators’ inclusive and global mind-sets were good for business: Venetians have always been canny in commerce!

In 1907, Belgium became the first country to build a permanent structure in the Giardini to serve as its national pavilion. By 1914, seven national pavilions had been erected. Today 29 foreign countries have their own pavilions in the Giardini. The City of Venice also has her own gallery. And the hulking, white-walled jumble of buildings which sprawls across the northwestern portion of the grounds (this complex was formerly the Italian pavilion; but Italy’s Biennale exhibits are now housed in the Arsenale) has been repurposed as the Biennale’s Central Giardini Pavilion.

As promised, I shall restrain myself and will NOT pass (too much) critical judgement

about the Biennale exhibits which you’ll soon discover here. The profusion of images that follow will provide you with plenty of information: it’ll be easy for you to decide who your favorite artists are. But I DO ask that you consider—in this context of La Biennale’s undeniable status as the World’s Most Fabulous Contemporary Art Show—these two things:

*An Artist who has been chosen to be the sole representative of her nation has been given a daunting and thankless task. First and foremost, her work must remain true to her OWN creative vision: she must not pander…must not sell out.

But this Artist must also honor some essential characteristic of her particular country;

overall, her assemblage of pieces must enable a Viewer whose culture and heritage are

utterly different to understand something basic about the Artist’s nation.

*The STAGING of every single piece of art is of critical importance. It’s not enough for an Artist to present his work in a cavernous room and then tack his manifesto to a wall. On this Biggest of Big-Time Stages, serious showmanship is called for. Utilizing the architecture of his pavilion, the Artist ought to find the most dynamic ways for his creations to interact with the existing spaces of the gallery. Visitors to Biennale deserve to have their socks knocked off by the Artist’s work, and also by the impeccable manner in which that work is presented.

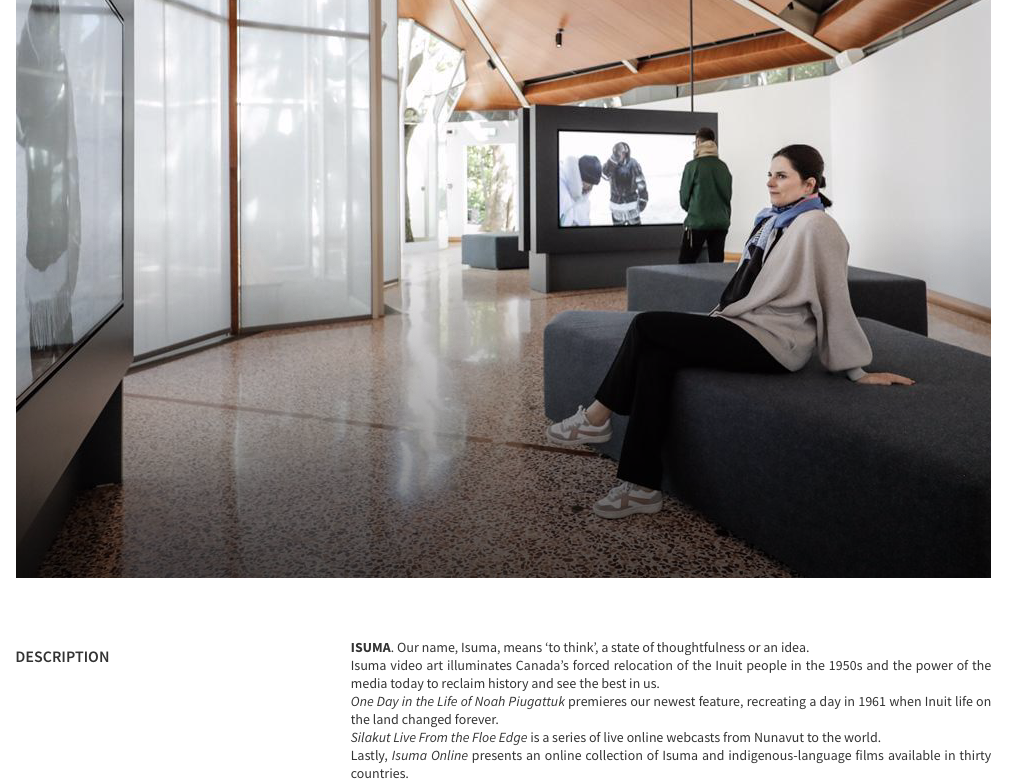

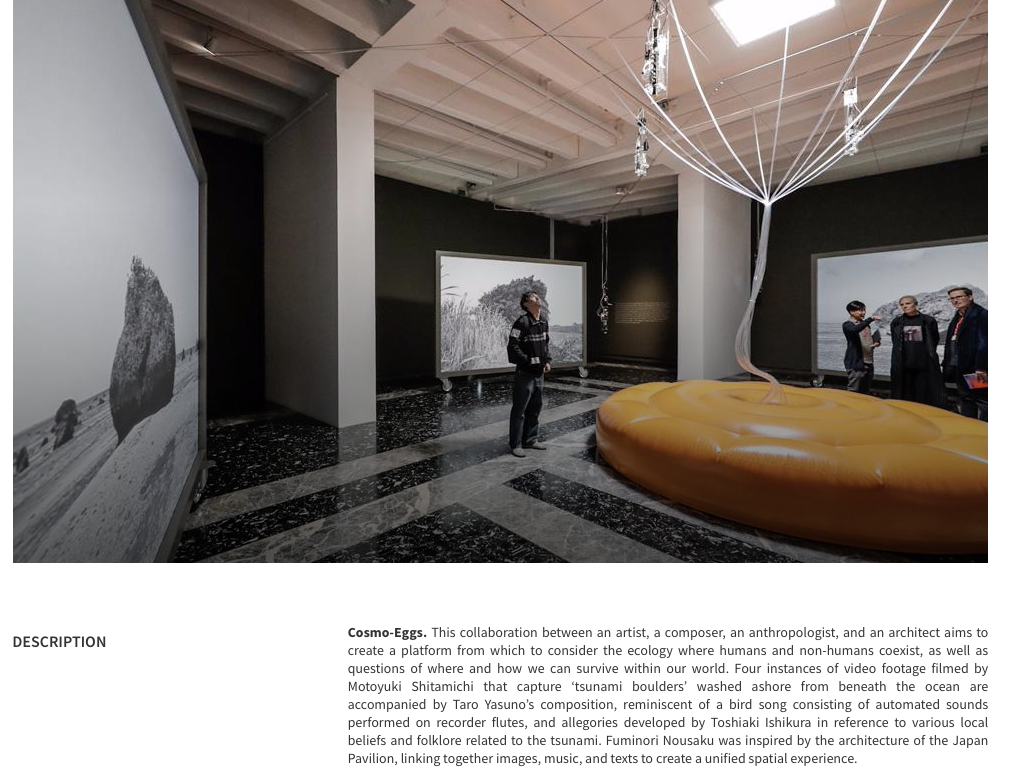

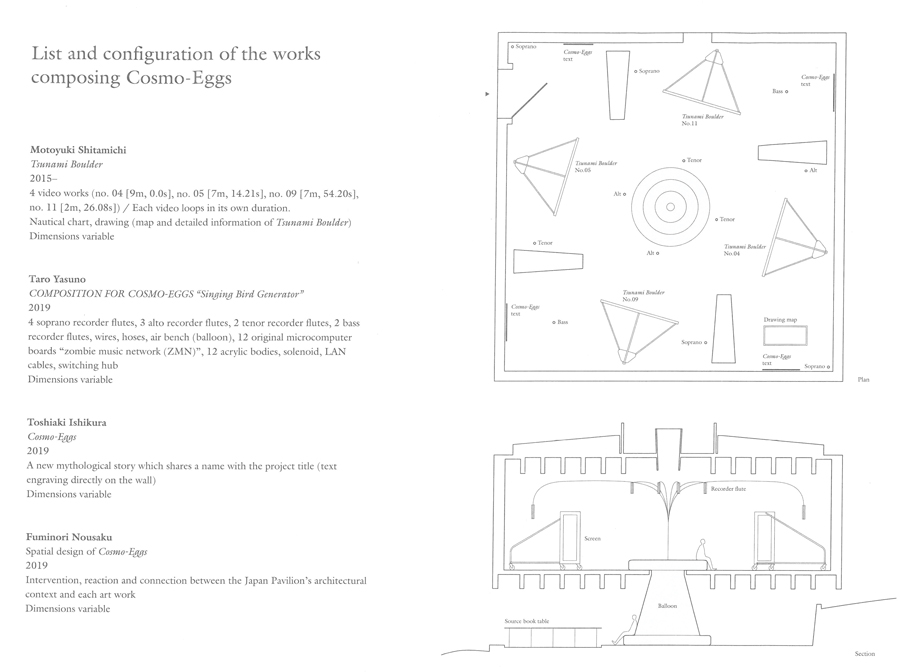

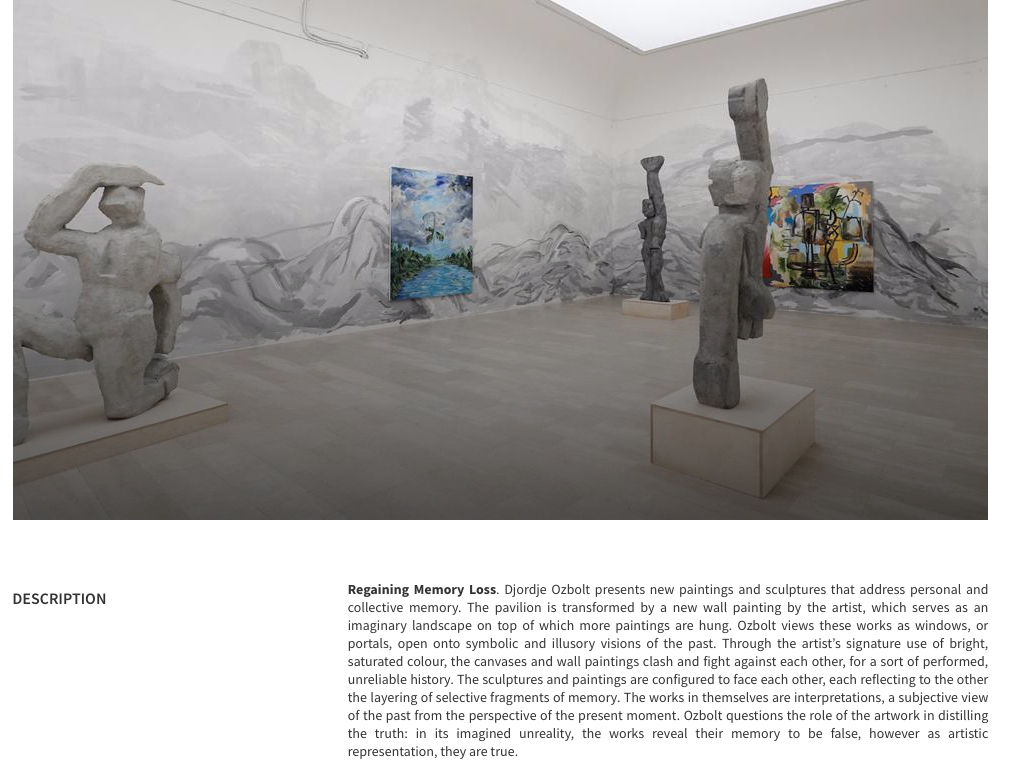

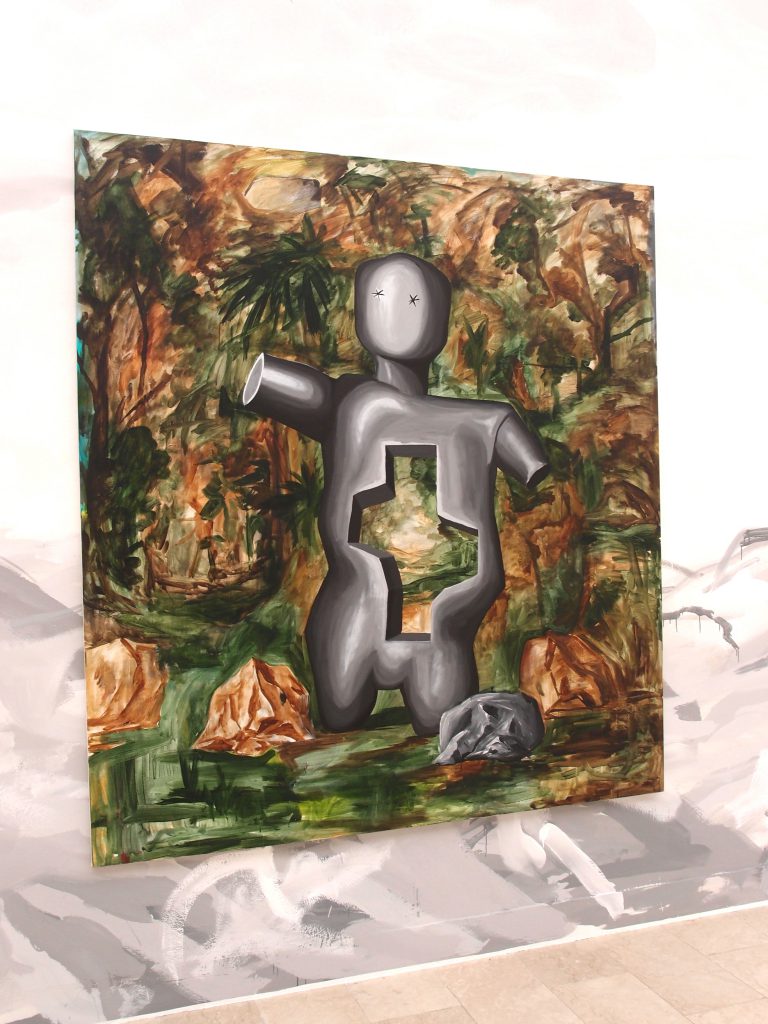

After having studied several years of Biennale Shows on a nearly-granular level, I cannot shake my conviction that filling a nation’s pavilion with the work of only one artist nearly always results in Visitors who feel bewildered, unsatisfied, or bored. For a smaller, mono-cultural country, the prospect of a single Artist doing a creditable job of describing some vital aspect of her homeland’s psyche is a tad less gloomy. But for a nation with a multi-cultural society, the creative viewpoint of a lone Artist—no matter HOW brilliant—cannot begin to be powerful enough to impart something elemental about the experience of BEING a citizen who is rooted in that particular culture. My sweet spots for the number of Artists to fill a nation’s Biennale pavilion seem to be 3 or 4. Italy ‘s trio (Enrico David, Chiara Fumai, Liliana Moro—& you’ll see their exhibit in Part Two of this DIARY, when we visit Biennale’s Arsenale showgrounds) and Japan’s quartet (Motoyuki Shitamichi, Taro Yasuno, Toshiaki Ishikura, Fuminori Nousaku) have created Shows which resonate: in their pavilions they miraculously combine poetry, social commentary, echoes of history, and swoon-worthy beauty…& all of this bound together by a frisson of unease…which is fitting in these peculiar times. But, of course, there CAN be exceptions: witness Djordje Ozbolt’s bravura solo-act (which examines personal and collective memory), in Serbia’s pavilion.

Bottom Line? Whether you’re an Exhibitor OR a Witness at La Biennale, the Show forces

you to really SEE, and to PONDER, and to FEEL.

May 9, 2019: Despite the chilly rain, I’m early (it’s 9:20AM), & I’m thus 3rd in the Press queue. Gates open at 10AM. Security is very tight: armed Police linger behind barriers & all attendees today will need to produce an Official Invitation, as well as their photo ID.

Just inside the Gate, heavy rain nearly obscures an illuminated billboard

Just through the Gate & behind me: Fellow Early-Birds: journalists, curators, and assorted VIPs. Many grumpy faces here today… due to the soggy weather?

Directly ahead is the Biennale’s Central Giardini Pavilion, which holds a hodgepodge of Individual Artists’ work, along with a bookstore, café, and administrative offices; I’ll visit this place later in the day.

On Press Days, people seem always to rush first down along this long avenue, toward the Great Britain pavilion, which is at the farthest end.

![]()

Exterior: Great Britain pavilion. This structure was originally a Café/Restaurant.

In 1909, it was converted into an exhibition space by British architect E.A.Rickards.

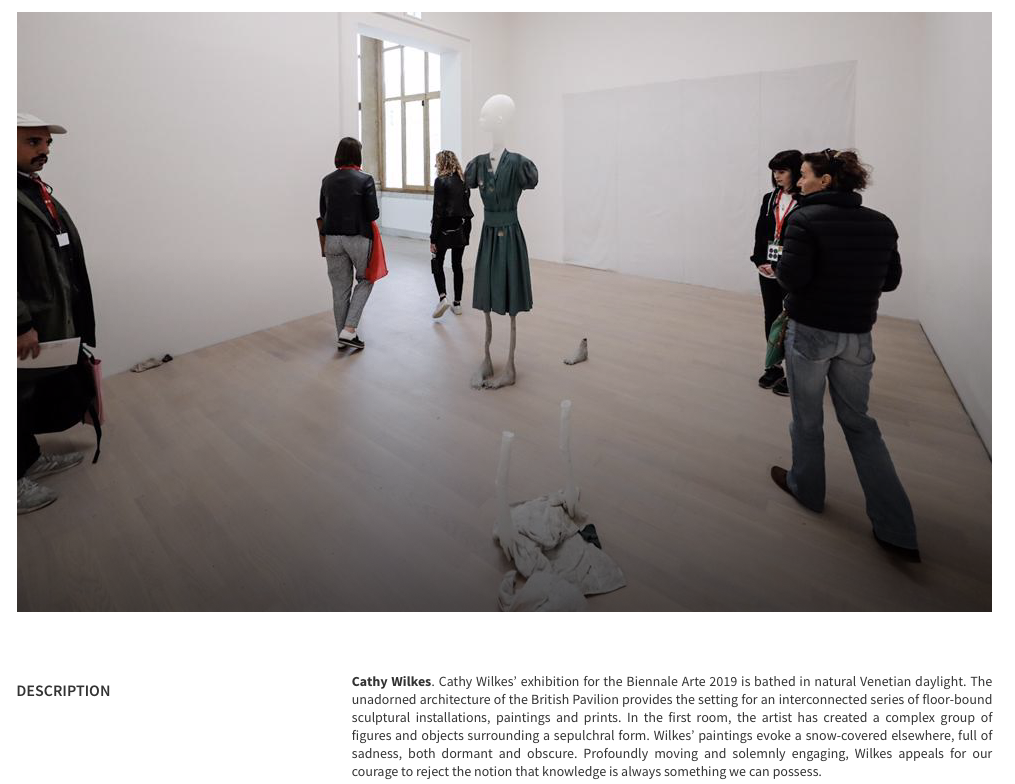

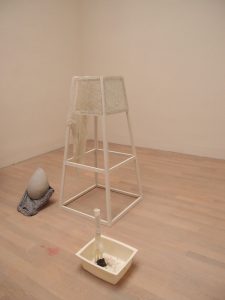

Great Britain: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Great Britain’s pavilion:

View from the steps of the Great Britain pavilion

![]()

Exterior: French pavilion…. not yet ready for Visitors on the morning of May 9th! Pavilion built in 1912. Architect: Umberto Bellotto.

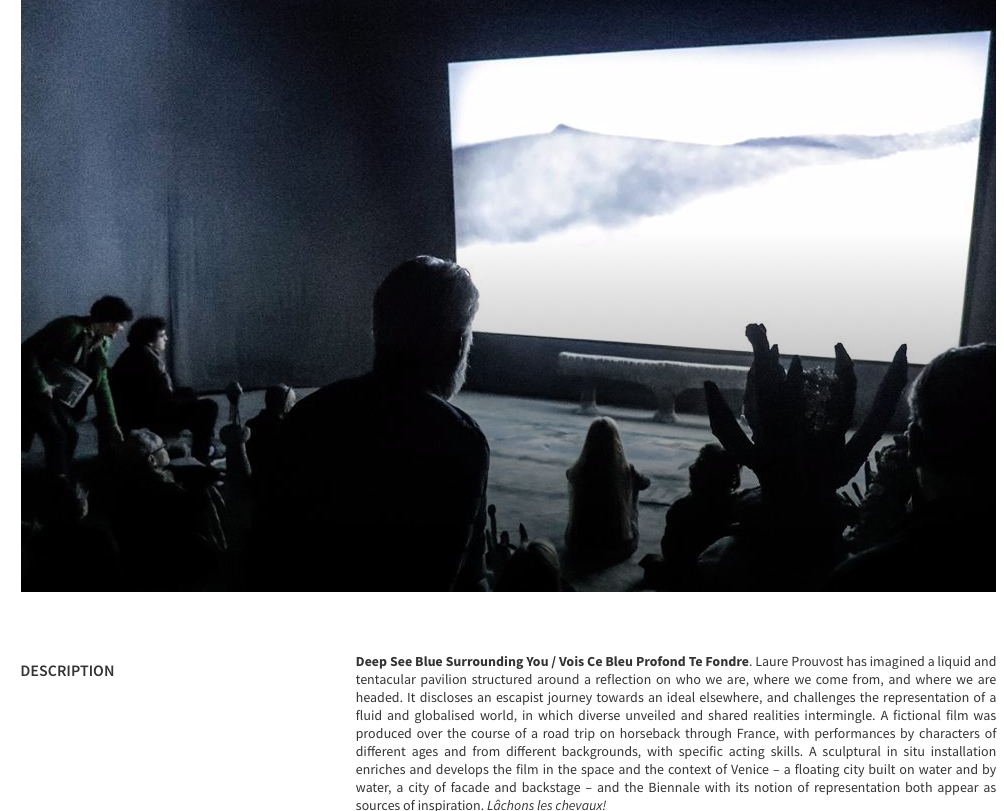

France: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

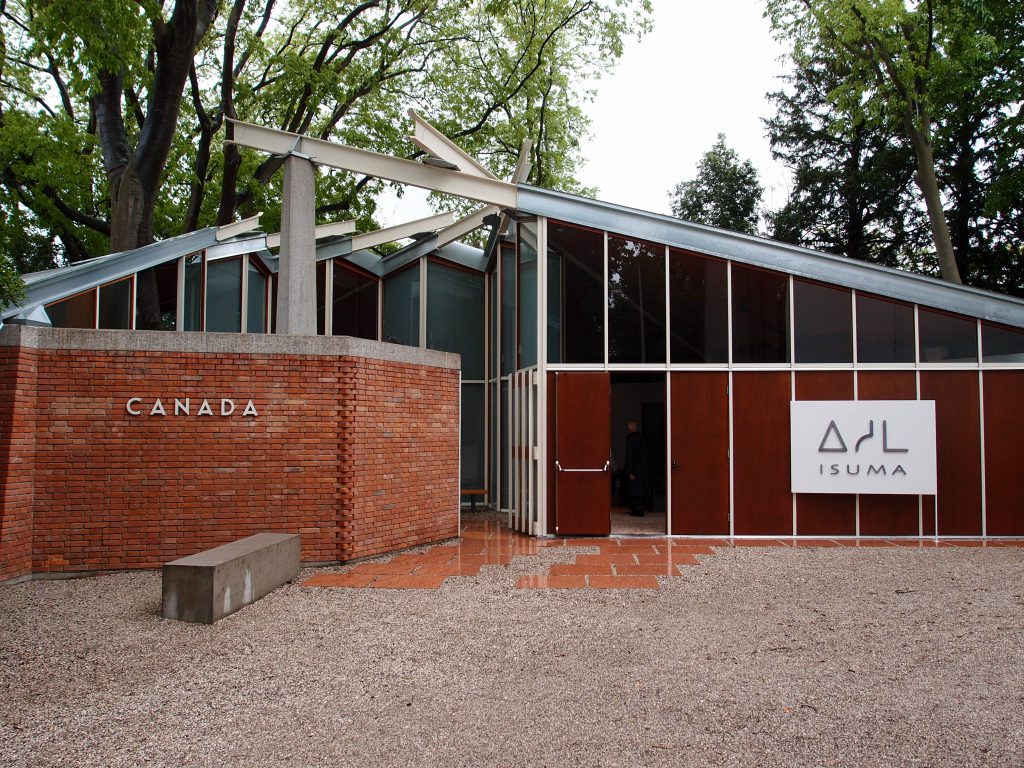

Exterior: Canada pavilion. Built in 1958. Architects: BBPR Group.

Canada: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

Exterior: Germany pavilion. Built in 1938. Architect: Ernst Haiger.

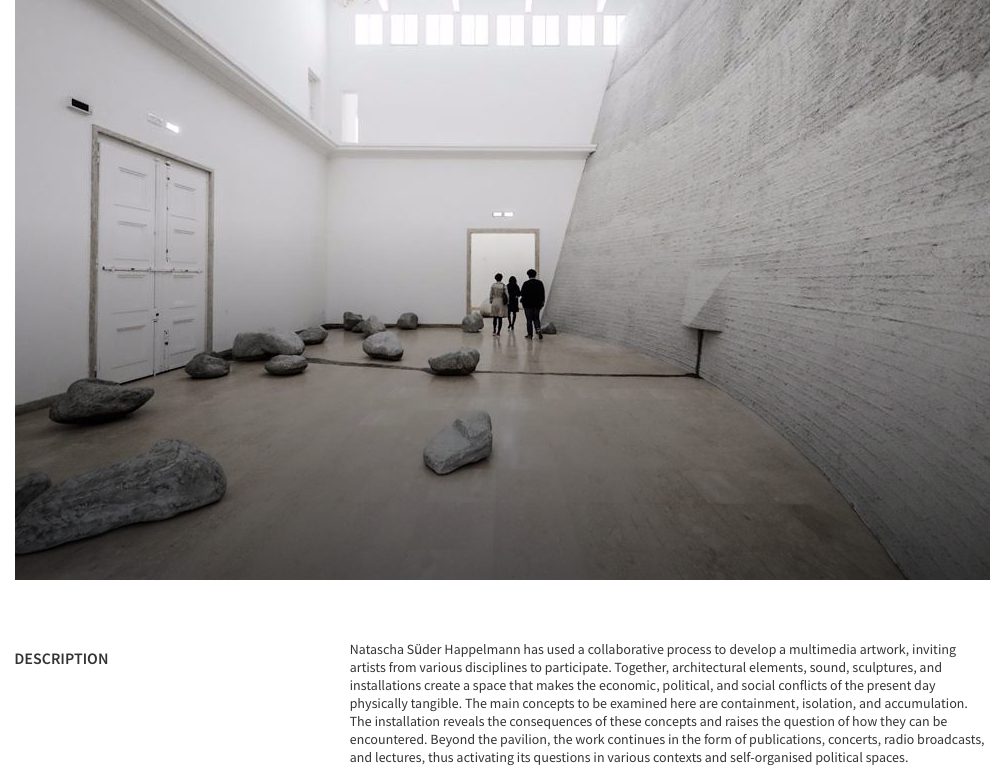

Germany: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

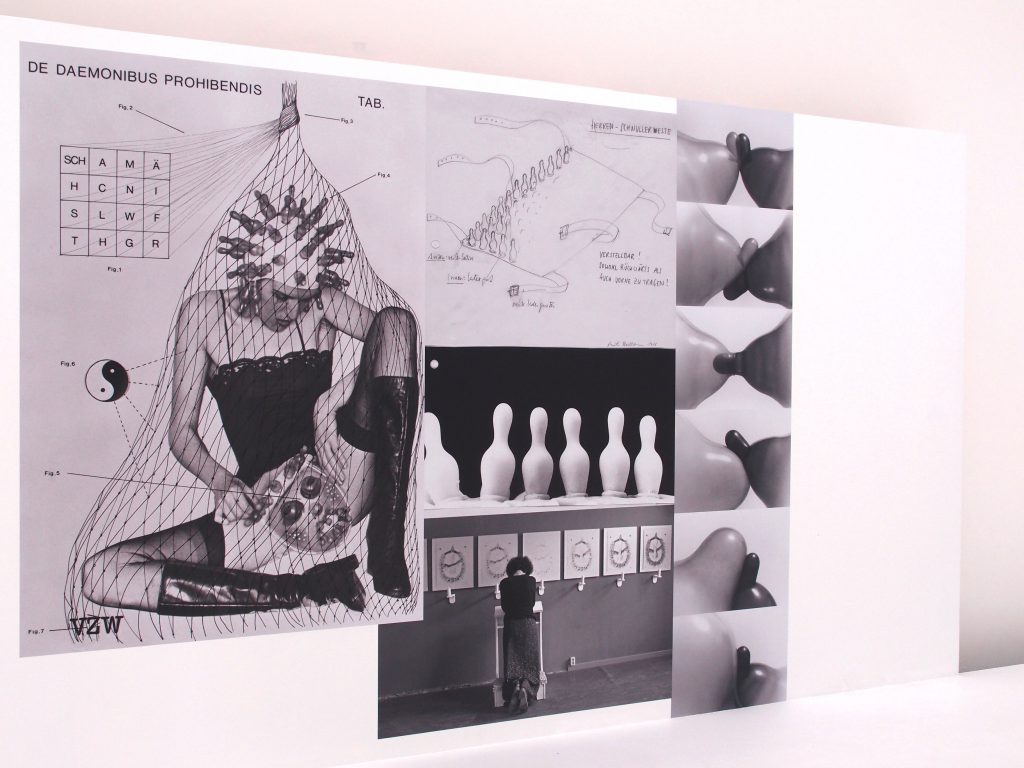

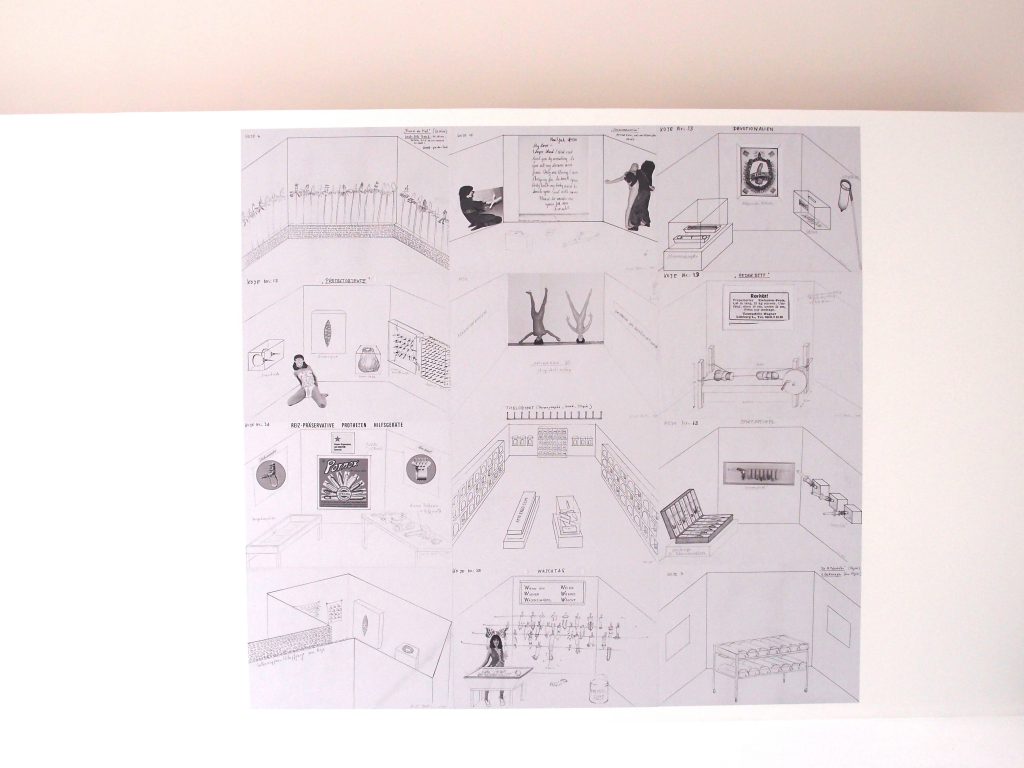

Inside the German pavilion:

![]()

Across from the German pavilion, a long line has suddenly formed. These folks are all

spurning the Czech pavilion (silly people… as you’ll soon discover) and are instead

waiting to enter the French pavilion (exterior not shown in this picture).

Me? Every minute is precious, so I refuse to waste time in queues.

![]()

Exterior: Japan pavilion. Built in 1956. Architect: Takamasa Yoshizaka.

Wet paving stones leading to the Japan pavilion

Japan: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Japan’s pavilion :

Section and floor plan of Japan pavilion

![]()

Exterior: Republic of Korea pavilion. Built in 1995.

Architects: Seok Chul Kim & Franco Mancuso

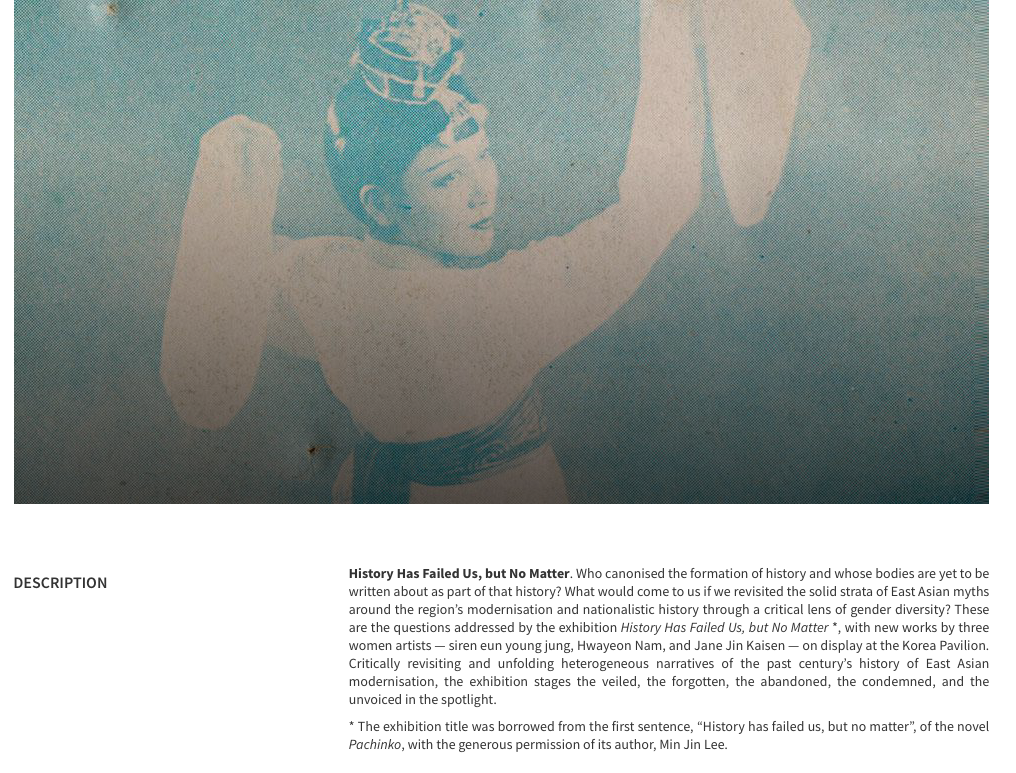

Republic of Korea: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Republic of Korea’s pavilion:

![]()

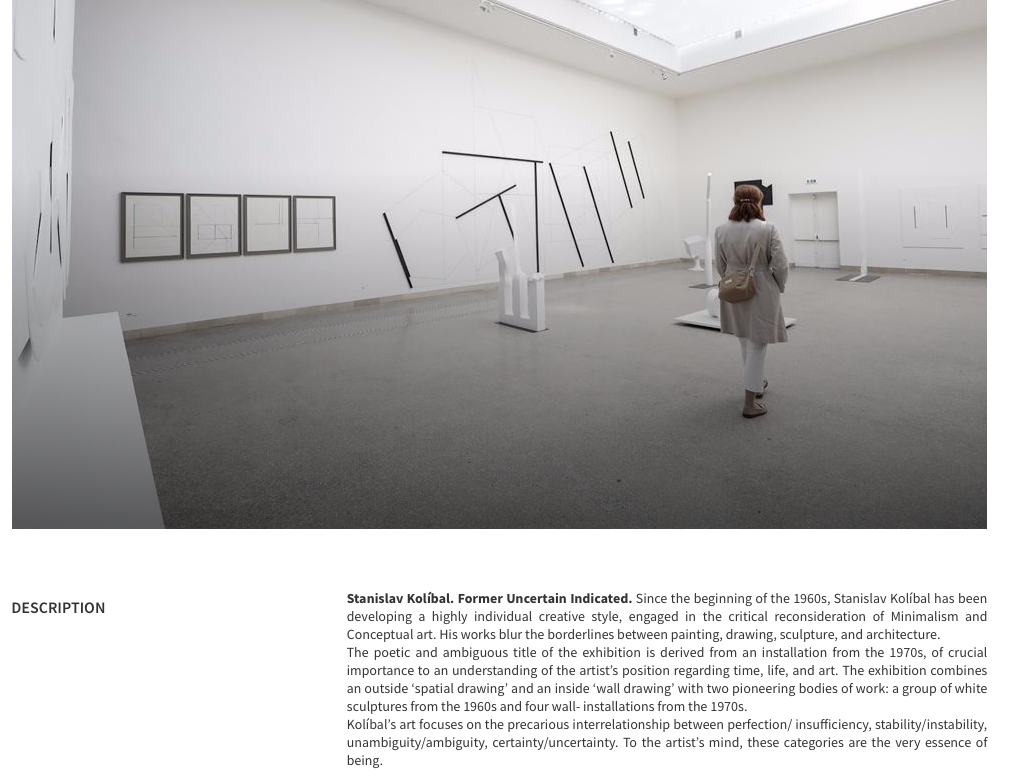

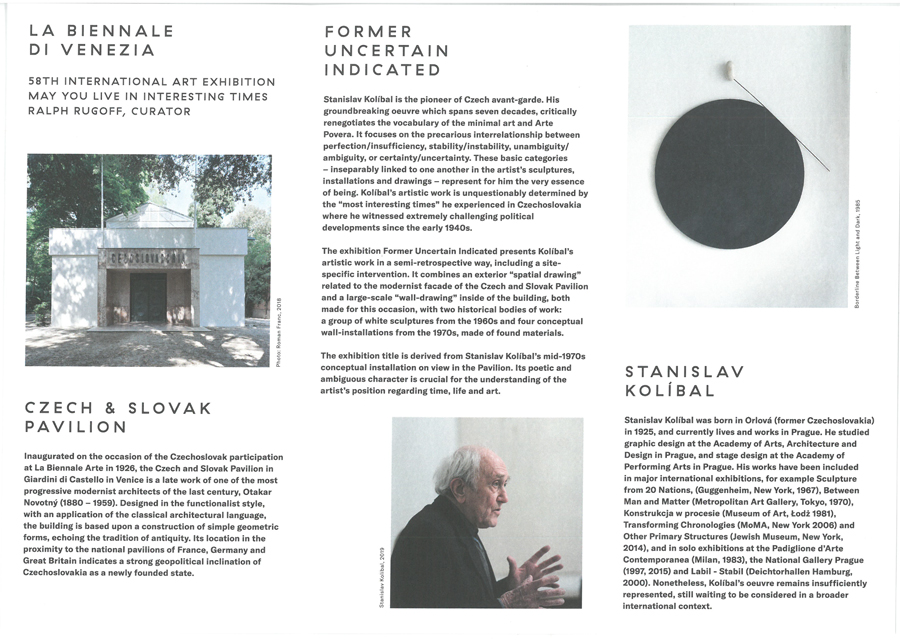

Czech Republic pavilion. Built 1926. Architect: Otakar Novotny.

Czech Republic: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Brochure for the Czech exhibit

Inside the Czech Republic’s pavilion:

Looking out from the front entry of the Czech pavilion

![]()

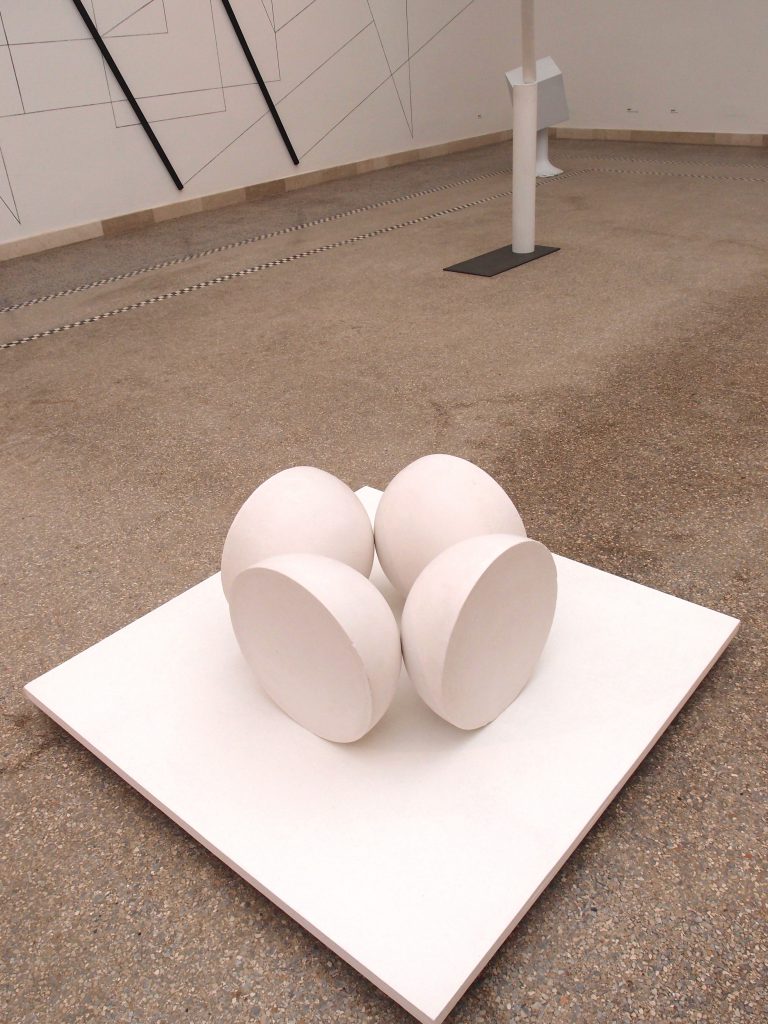

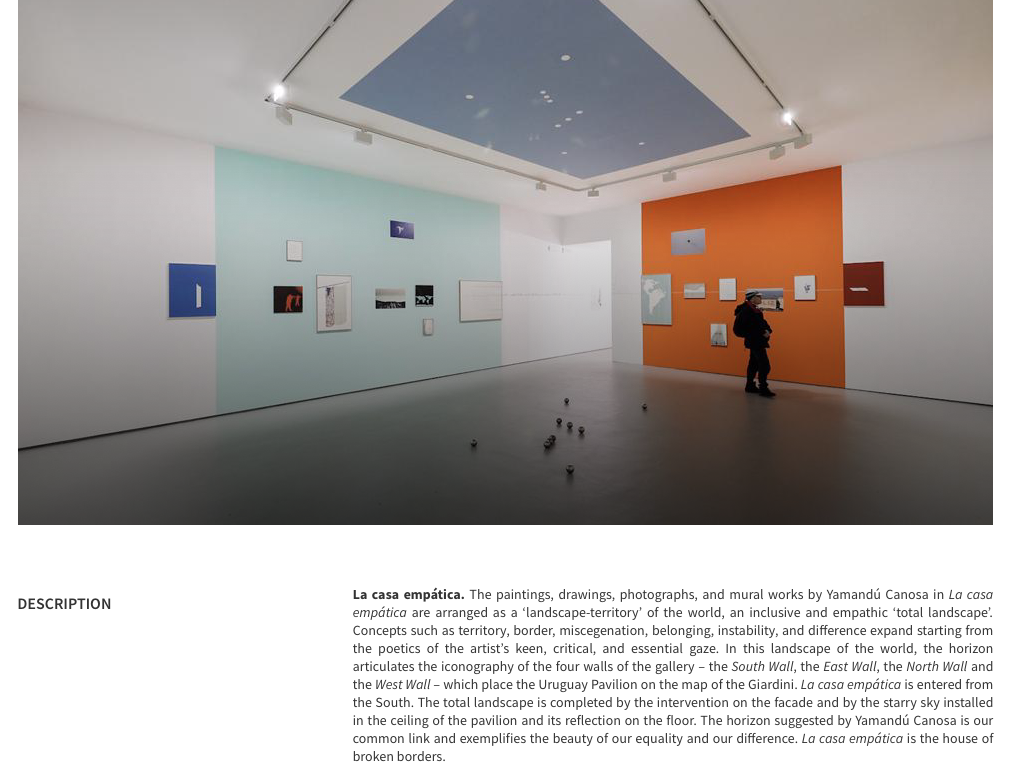

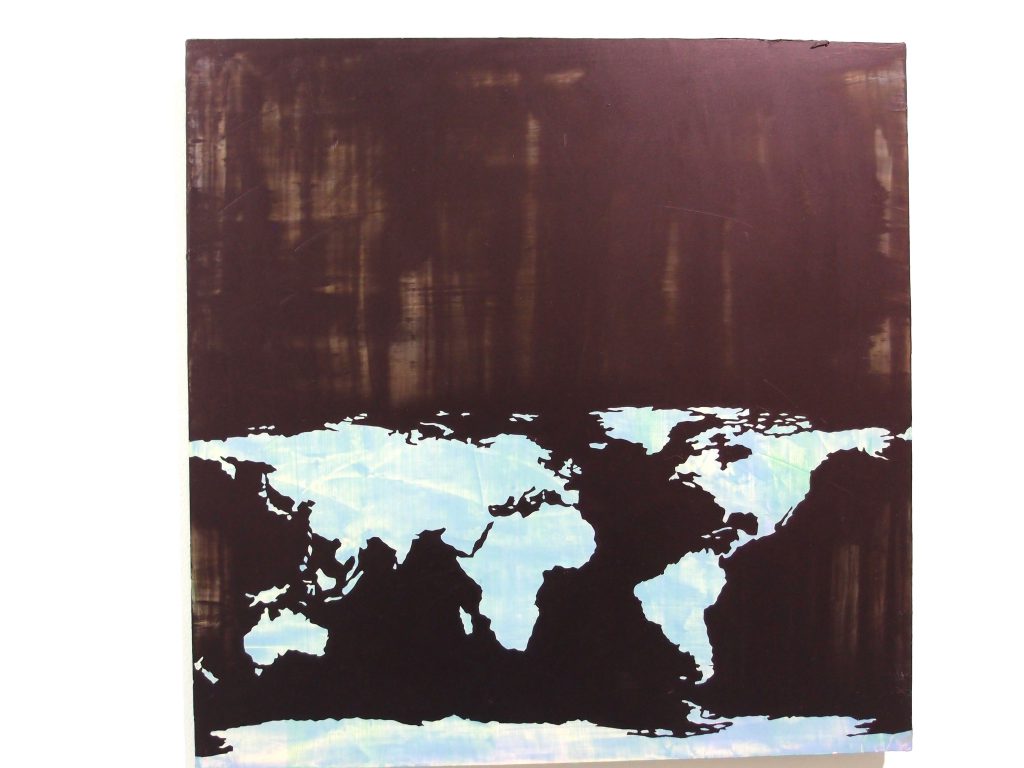

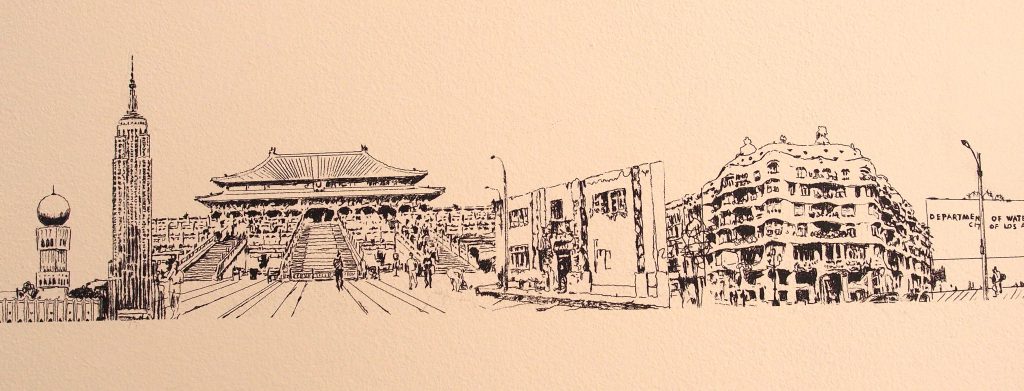

Exterior: Uruguay pavilion. Originally a warehouse built for the 1958 Biennale, in

1960 it was converted into gallery space

Uruguay: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Uruguay’s pavilion:

Departing from the exhibit, I also admire the steps of Uruguay’s pavilion.

![]()

As sunshine began to break through the clouds, I wandered down to the Rio dei Giardini, and crossed the water, so I could get a good look back up at the black boxes of the Australian pavilion.

This pavilion was built in 2015 by Architects Denton, Corker & Marshall.

The view down the Rio is out towards the island of

San Giorgio Maggiore (which always seems to be floating upon the Canale di San Marco).

I then Re-crossed the Rio, and climbed up to the 2nd floor entry porch of Australia’s pavilion. From that porch I had this view across

the Rio dei Giardini, into the northern-most section of the Biennale’s Giardini.

Australia: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Australia’s pavilion

![]()

I’m behind the pavilions of Uruguay and Australia , and am strolling toward

Rio dei Giardini.

View across the Rio dei Giardini. The brick building on the opposite shore is the Greek pavilion

I’m on the southern embankment of Rio dei Giardini. Notice the absence of gondolas! Castello is a neighborhood where Italians still actually live and work; the boats on this Rio are all hauling essential goods. During my long hours of art-looking, not a single, singing gondolier appeared anywhere near to any of the Biennale’s waterfronts. I was grateful for this absence of gondolas because, during other days, as I was taking care of business in Venice’s San Marco area, my eardrums throbbed and threatened to explode, as they heard hundreds of gondoliers warbling their renditions of “Volare.”

Having once again crossed the bridge that spans the Rio dei Giardini,

I approach Austria’s pavilion

![]()

Exterior: Austria pavilion. Built in 1934. Architect: Josef Hoffman.

Austria: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Austria’s pavilion:

![]()

Exterior: Republic of Serbia pavilion (formerly called Yugoslavia). Built in 1932.

Architect: Brenno del Giudice.

In 1992, following the breakup of Yugoslavia, Serbia & Montenegro formed a new Republic,

now known as Serbia.

Republic of Serbia: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Serbia’s pavilion:

![]()

Exterior: Poland pavilion. Built in 1932. Architect: Brenno del Giudice.

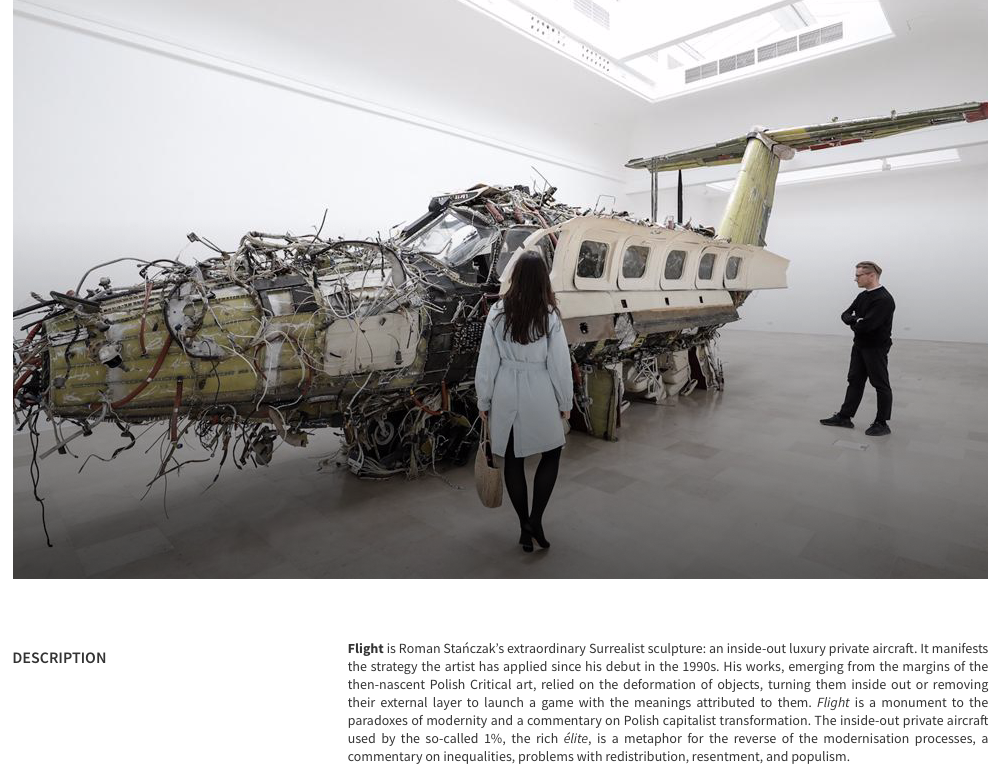

Poland: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Poland’s pavilion:

![]()

Exterior: Romania pavilion. Built in 1932. Architect: Brenno del Giudice.

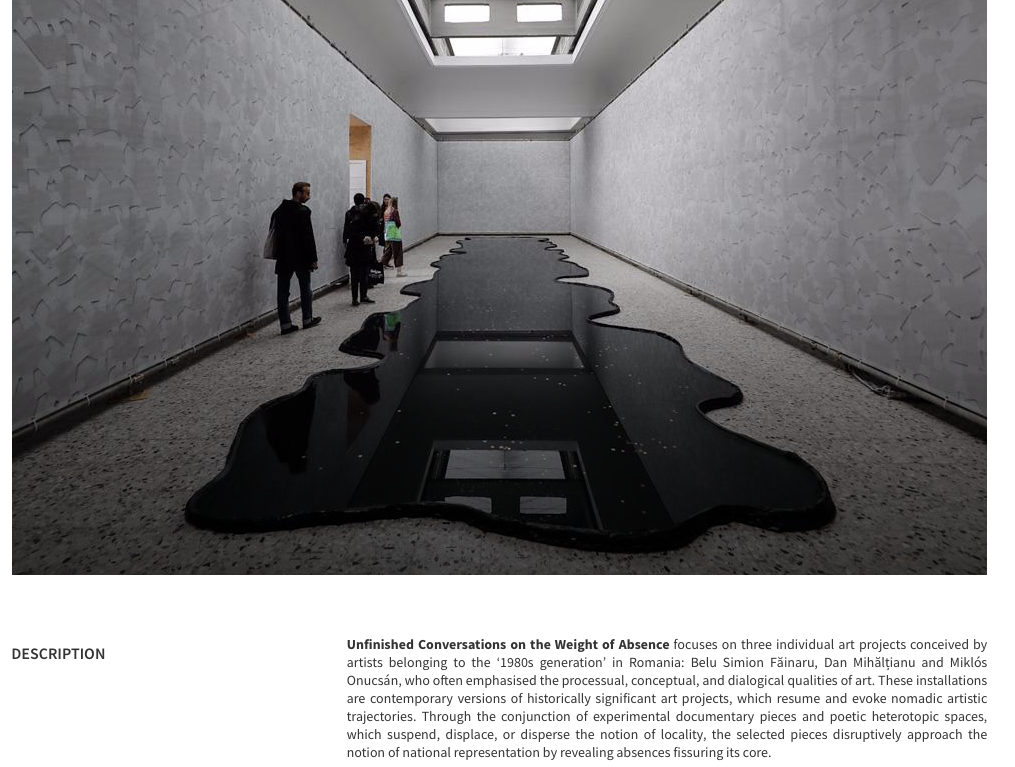

Romania: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Romania’s pavilion:

![]()

Exterior: Greece pavilion. Built 1934. Architects: M. Papandreou & B. del Giudice

And abruptly, the weather had changed…for the better:

Now sunny & hot (but humid!). I frantically began peeling off my outer layers of clothing.

More Exterior details of Greece’s pavilion:

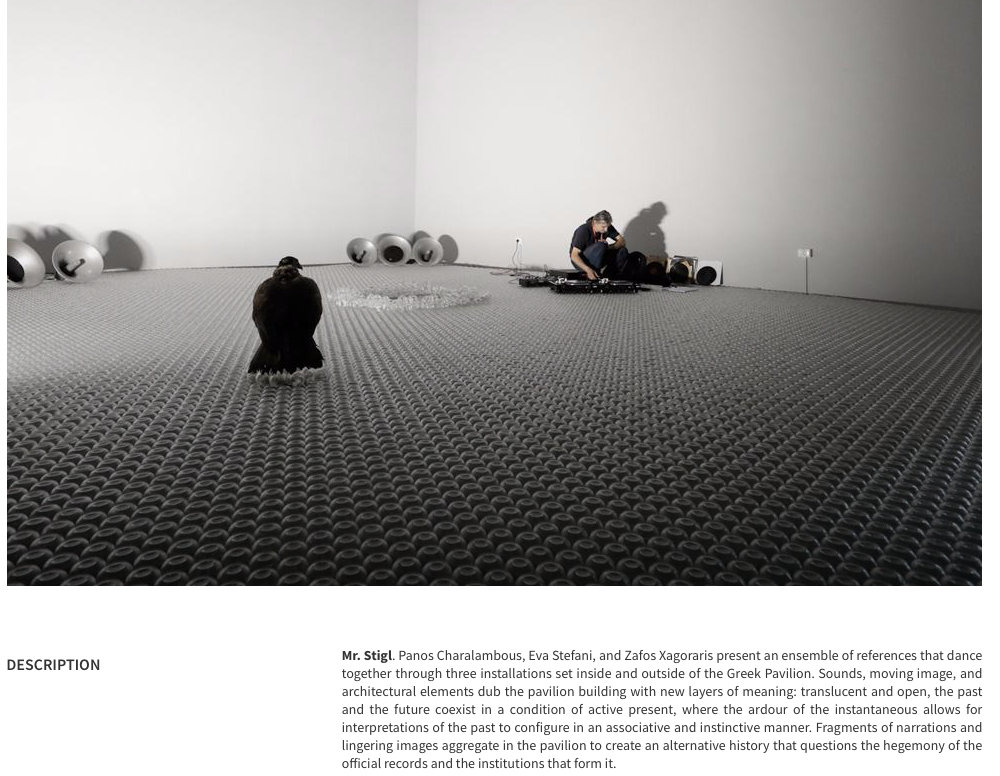

Greece: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Greece’s pavilion:

My view from the front steps of Greece’s pavilion

![]()

Exterior: Egypt pavilion. Built in 1932. Architect: Brenno del Giudice.

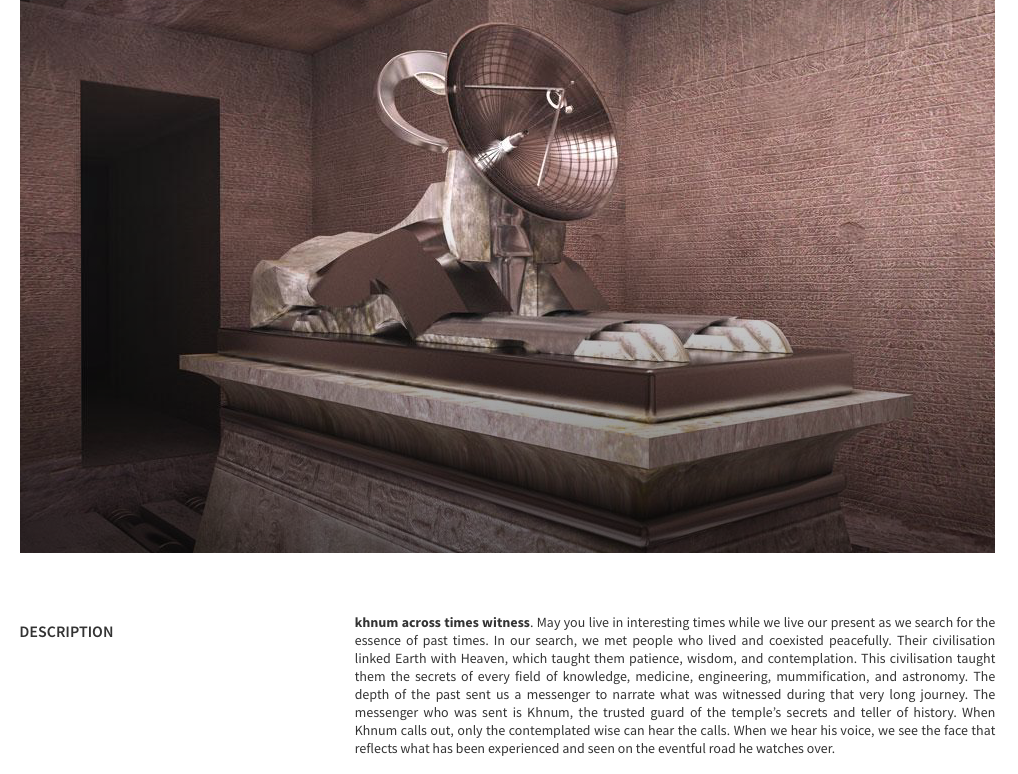

Egypt: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside Egypt’s pavilion:

![]()

Exterior: The Venice Pavilion. Built in 1932. Architect: Brenno del Giudice

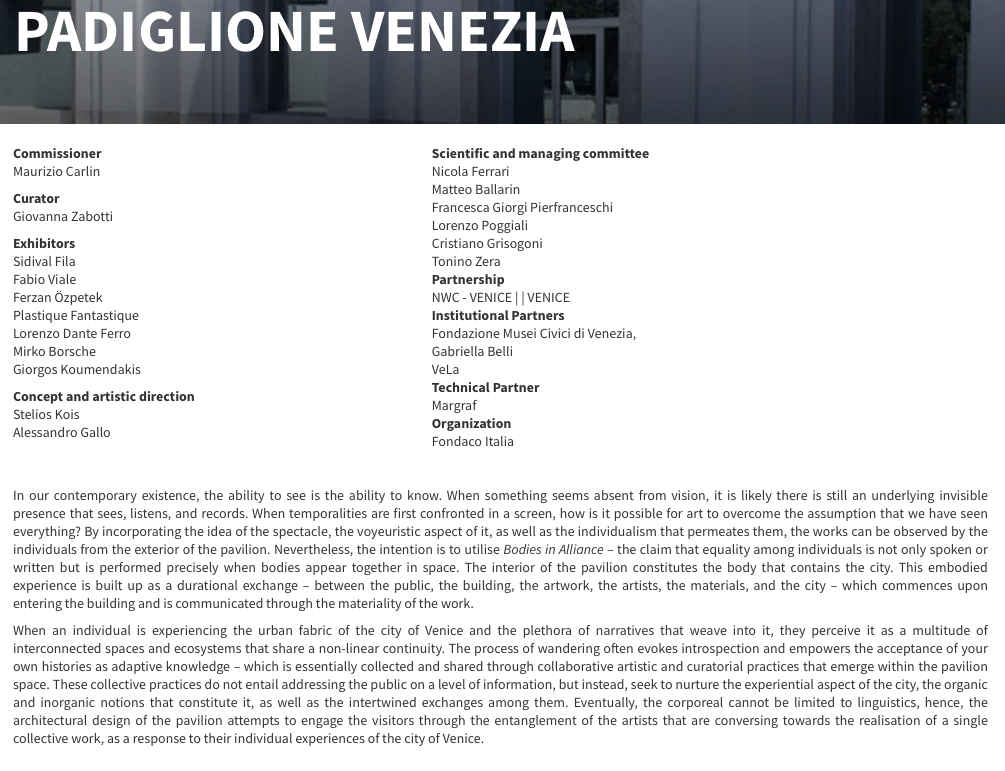

The Venice Pavilion: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Floor plan of the Venice pavilion

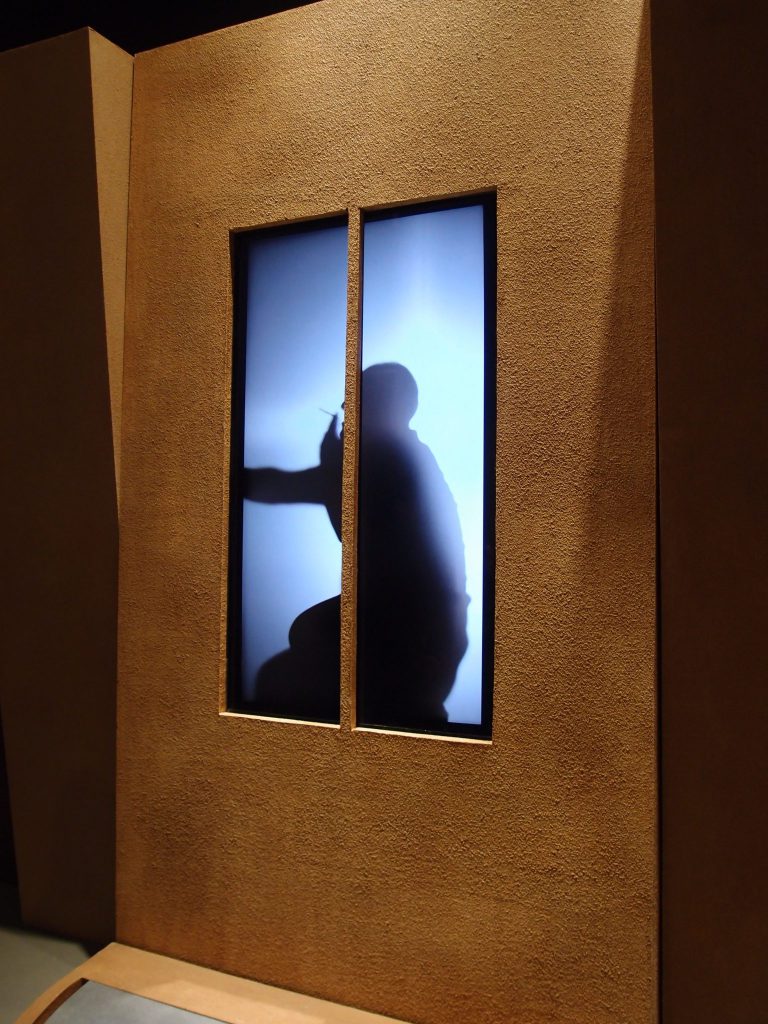

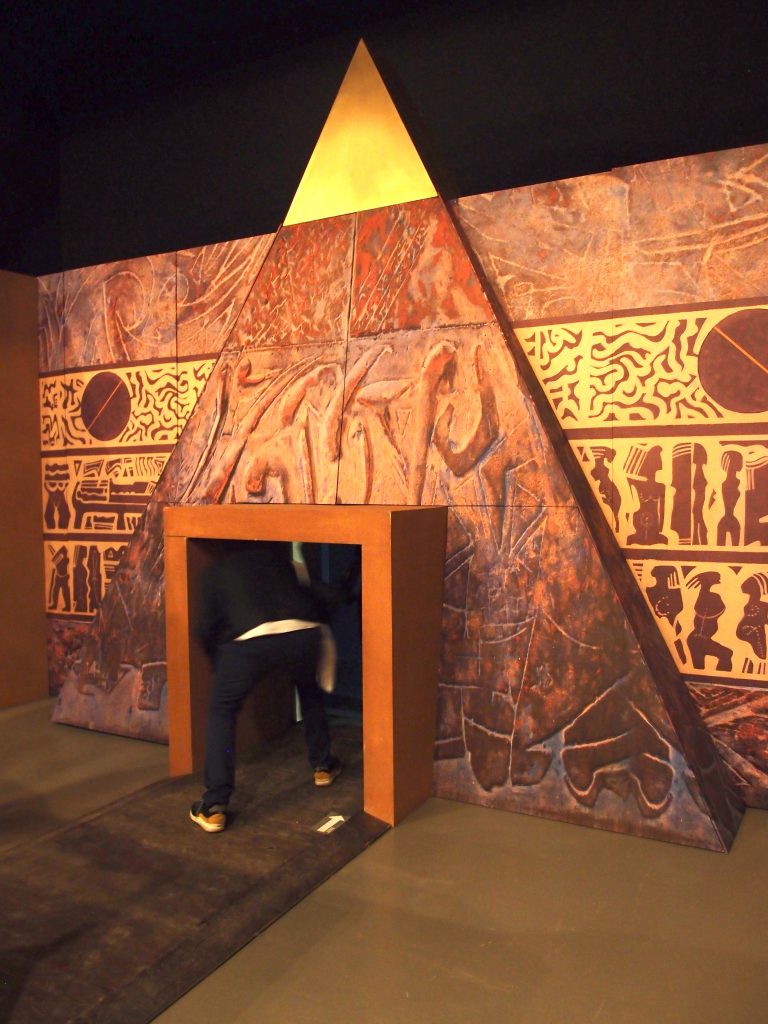

Inside the Venice pavilion:

![]()

Having visited all of the pavilions on the northern shores of the Rio dei Giardini,

I went back across the bridge, and headed into the now-crowded, central Giardini.

But, mid-way along the bridge, I paused for another look down along Rio dei Giardini, into Castello’s neighborhoods.

![]()

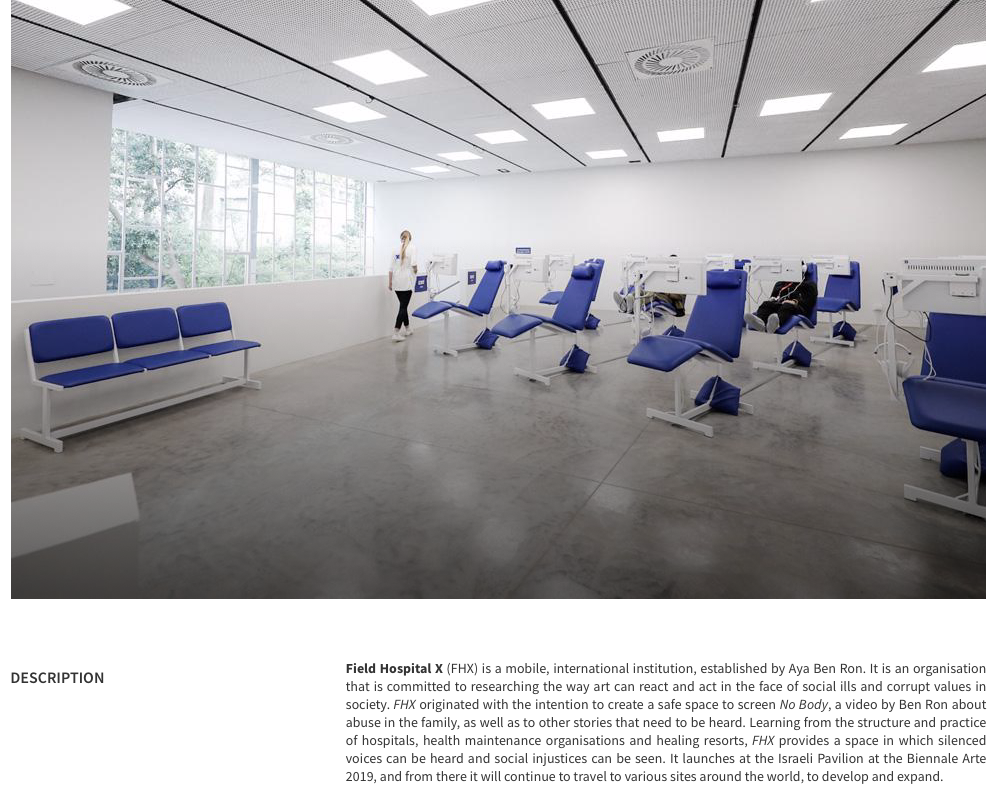

Exterior: Israel pavilion. Built in 1952. Architect: Zeev Rechter.

I’d been eager to go inside Israel’s pavilion, but the queue outside was

daunting. Rattled at not being able to see their exhibit, I forgot to take a photo of the

Pavilion’s exterior. This image courtesy of Field Hospital X.

Israel: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

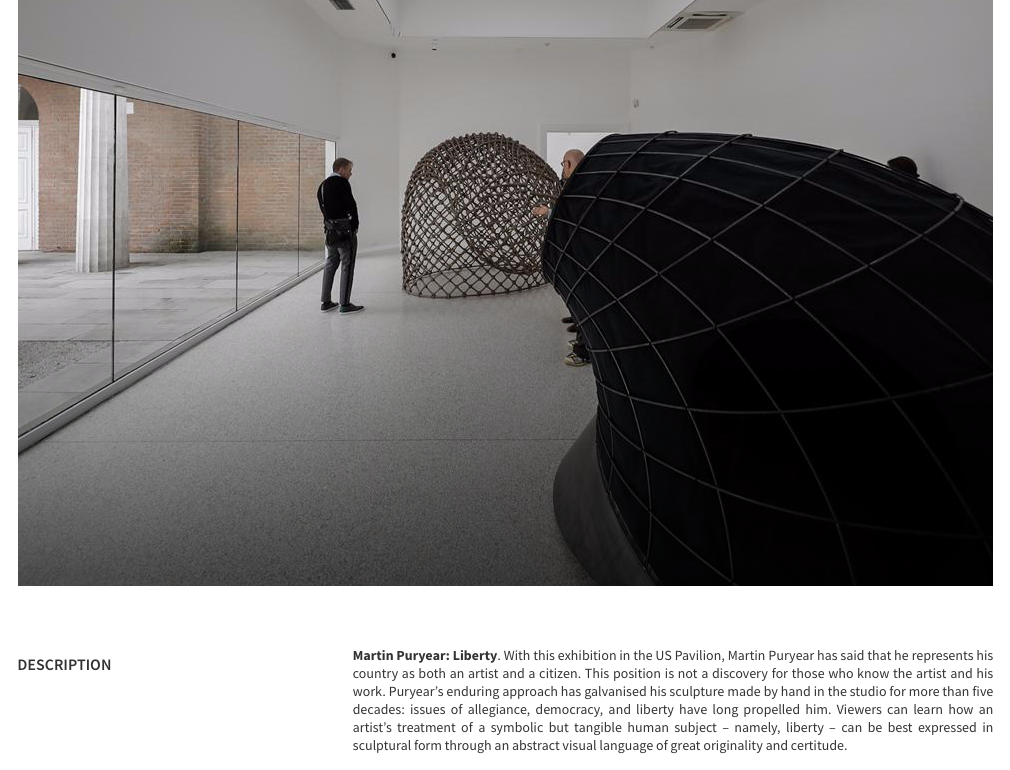

Exterior: United States of America pavilion. Built in 1930. Architects: Aldrich & Delano

Earlier in the day, I’d passed the USA pavilion, which had delayed its

opening until the completion of artist Martin Puryear’s press conference.

Per usual, I saw no advantage to milling around in a crowd of journalists (shown here…and all of them looking very bored) and so I continued with my visits to other pavilions.

USA: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Hours later, with the press conference over and the worst of the crowds gone, I entered the USA pavilion’s courtyard.

Inside the USA pavilion:

Outside, in the USA pavilion’s front courtyard:

![]()

Exterior: Nordic Countries Pavilion–Finland, Norway & Sweden. Circa 1962 photo (just after construction was completed) of the Nordic Countries pavilion. As of 2019, serious structural repairs are being considered. Architecturally, this is arguably the most extraordinary pavilion in the Giardini. Architect: Sverre Fehn.

Photo courtesy of Sverre Fehn.

Nordic Countries: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside the pavilion of the Nordic Countries:

![]()

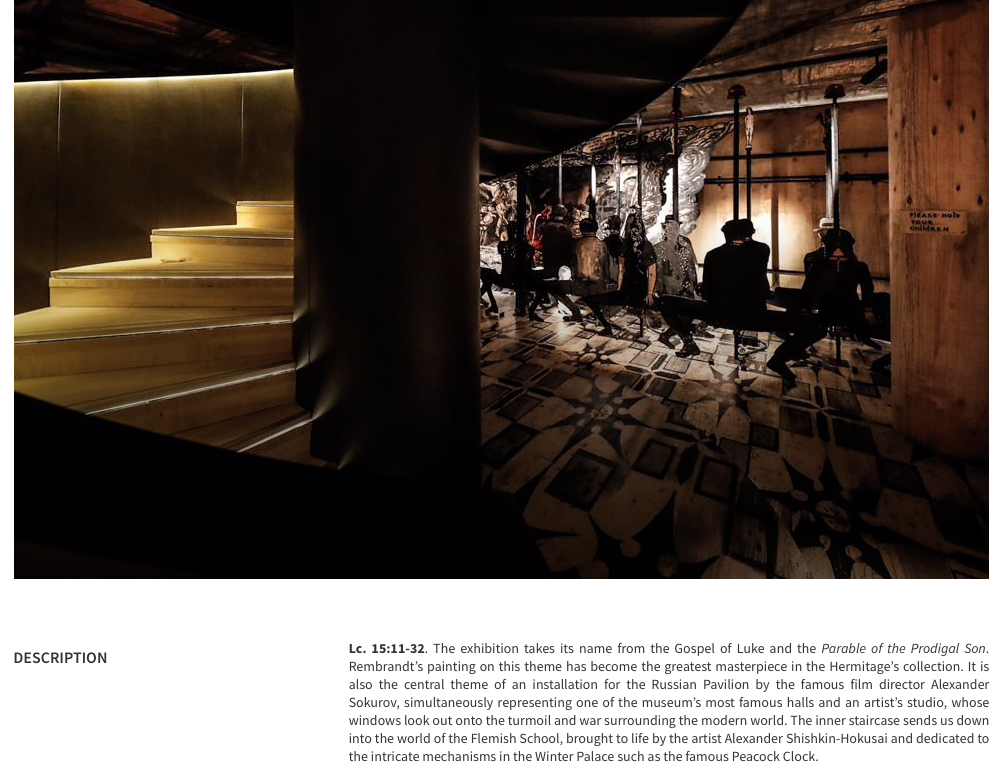

Exterior: Russia pavilion. Built in 1914. Architect: Aleksej V.Scusev.

The place was locked tight, with this notice on the door:

“Ticketed Admittance Only.” SO….No visit for me, to Russia’s House.

Russia: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

Exterior: Denmark pavilion. Built in 1932. Architect: Carl Brummer. Expanded in 1958. Architect: Peter Koch

Exquisite tile, at the entry to Denmark pavilion

Denmark: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

Venezuela pavilion. Built 1954. Architect: Carlo Scarpa.

An exotic-looking Lady, outside Venezuela’s pavilion

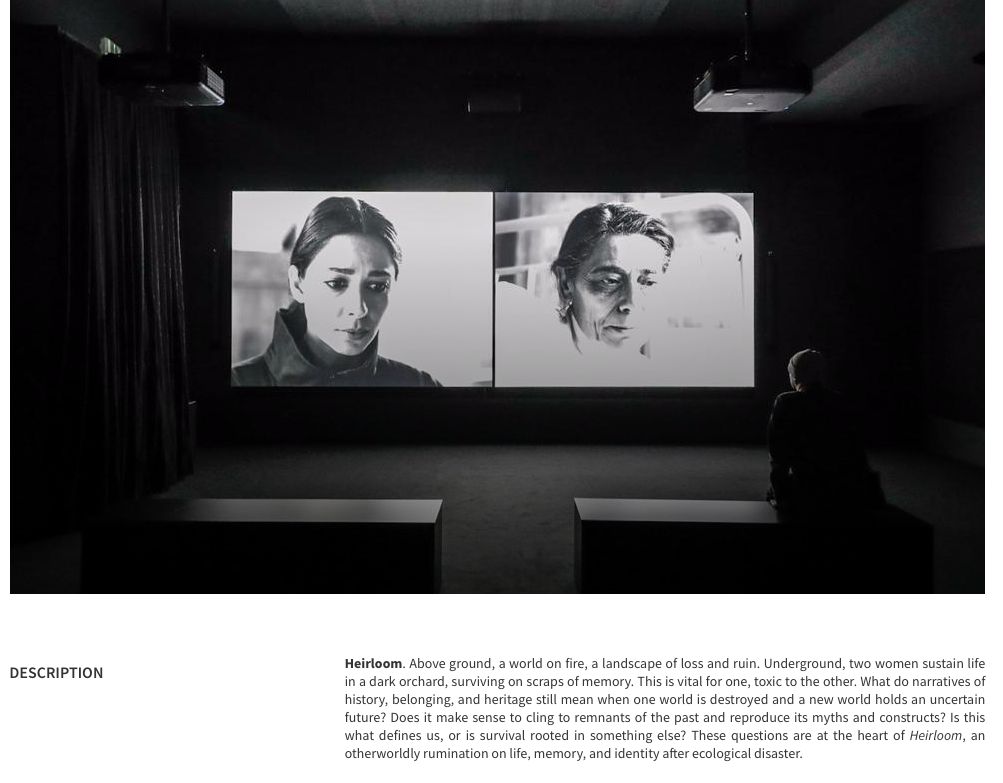

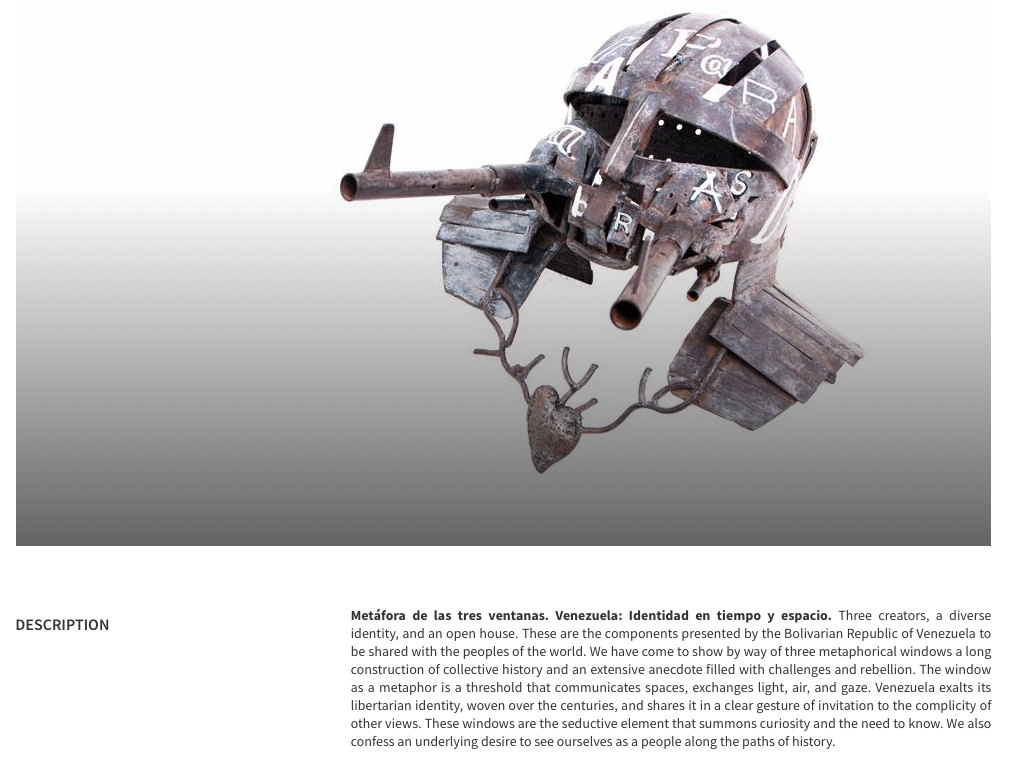

Venezuela: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

Exterior: Switzerland pavilion. Built in 1952. Architect: Bruno Giacometti. Another exhibit on lockdown, until the Artist’s press conference.

Switzerland: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

Exterior: Spain pavilion. Built in 1922. Architect: Javier De Luque. Façade renovated in 1952. Architect: Joaquin Vaquero Palacios

Spain: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside the Spain pavilion:

![]()

Exterior: Belgium pavilion. Built in 1907. Architect: Leon Sneyens

Belgium: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside the Belgium pavilion:

![]()

Exterior: The Netherlands pavilion. Built in 1953. Architect: Gerrit Thomas Rietveld

The Netherlands: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside The Netherlands pavilion:

![]()

Exterior : La Biennale’s Central Giardini Pavilion

I knew that once I went inside, as always, the Giardini’s Central Pavilion would

be a Madhouse-in-a-Maze:

Central Pavilion floor plan

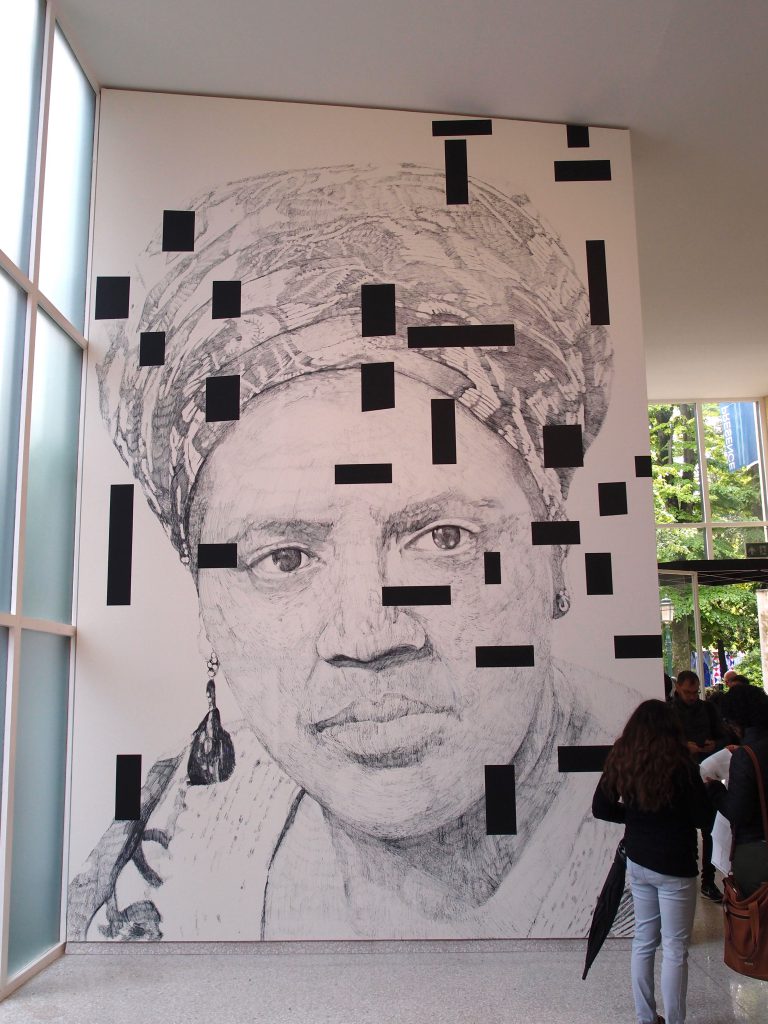

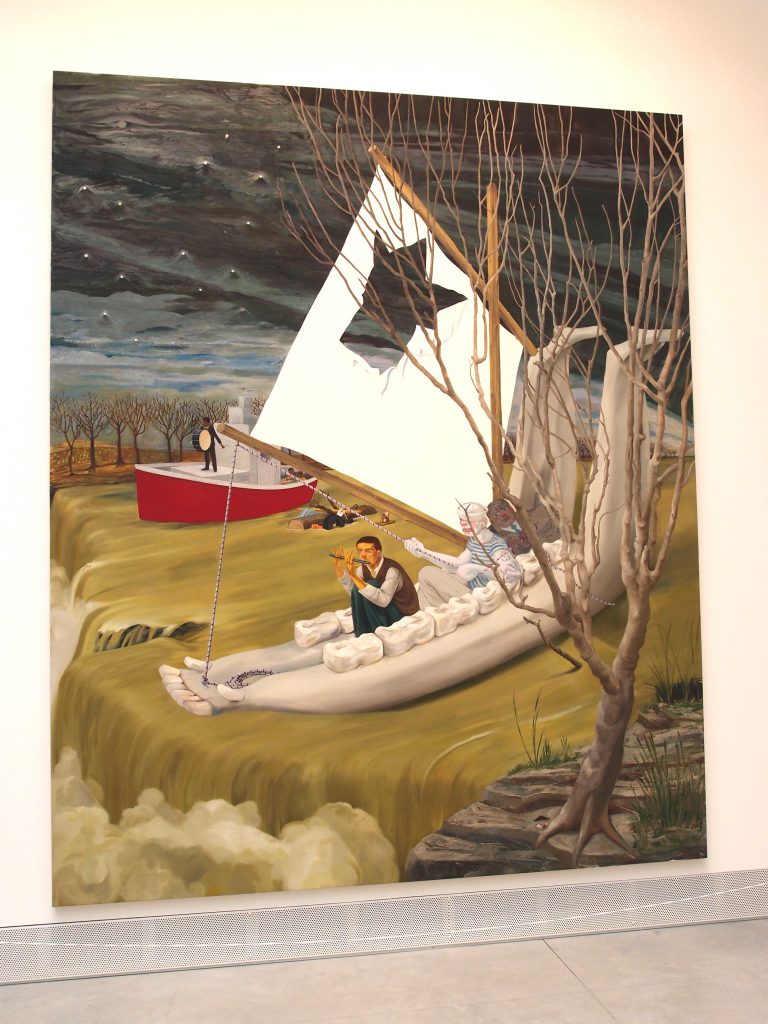

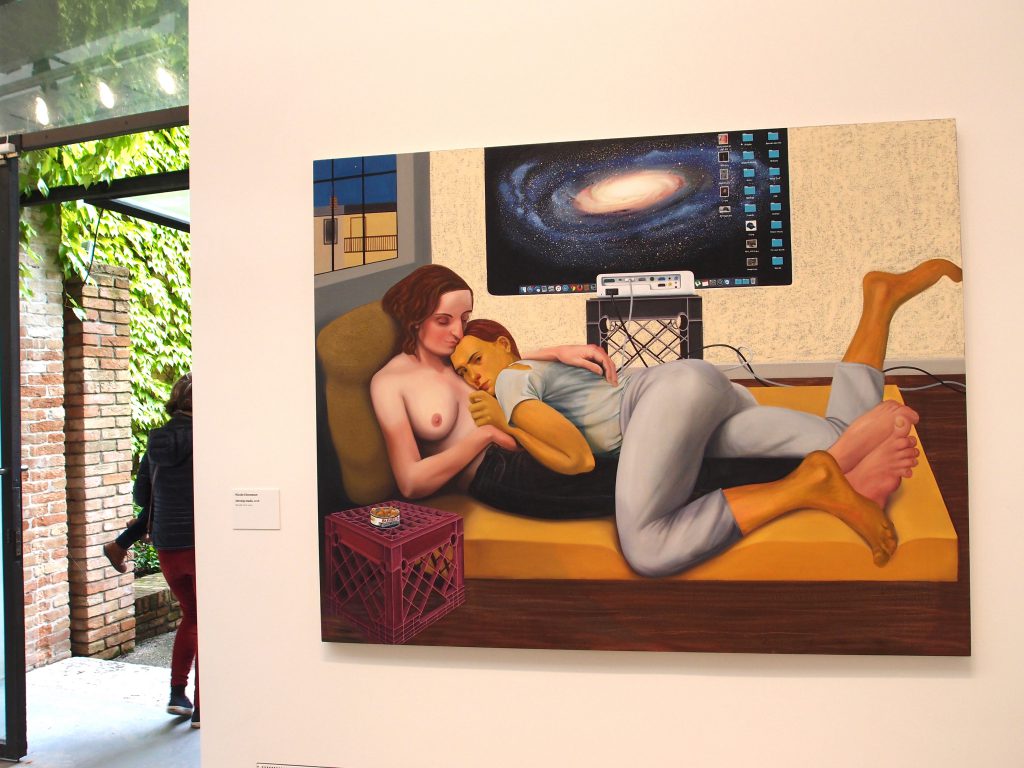

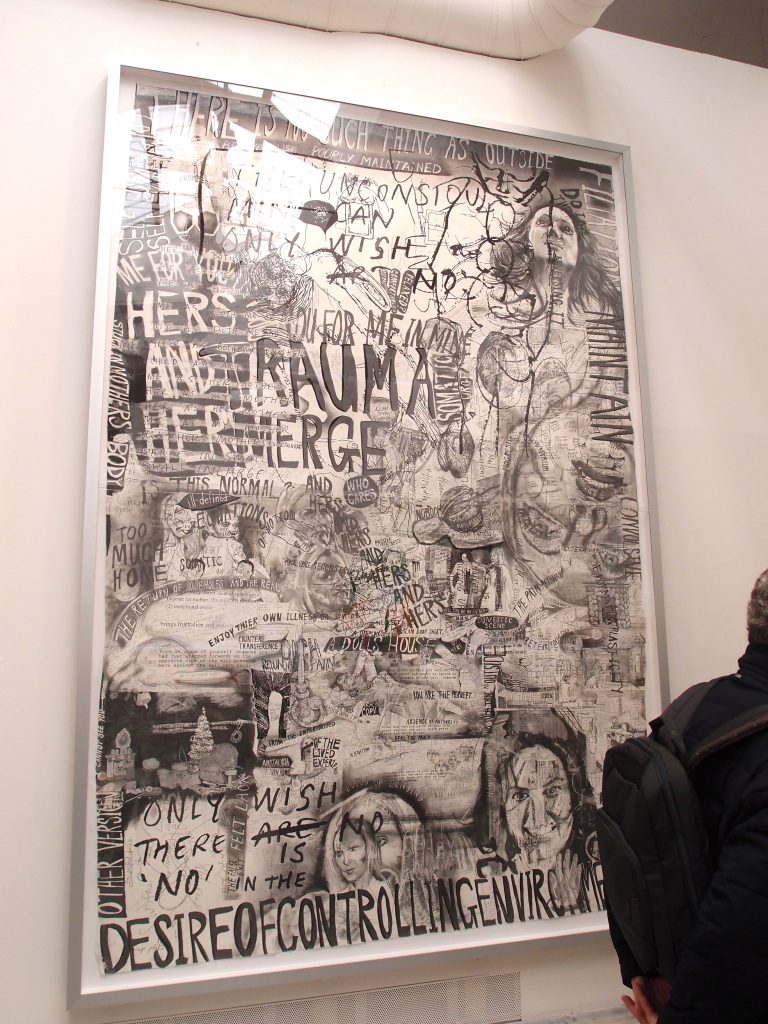

Despite my abhorrence of crowds, I gritted my teeth, and entered. Here’s just a fraction of what I found:

Famished, and utterly sick of the mob-scene, I fled from the Central Pavilion’s galleries,and zeroed in on the nearby Caffeteria, which turned out to

be equally jam-packed:

But now that I think about it, I realize that, in past years, I’ve never been able to bring myself to eat a meal in this dizzyingly-decorated restaurant! As described on La Biennale’s Website: “The Caffeteria, designed by

Tobias Rehberger, is painted according to the pictorial style of RAZZLE DAZZLE (used especially on warships during World War I.” Somehow, camouflage graphics do nothing

to encourage healthy digestion. And so, as in past visits to Biennale, I managed my

hunger pangs with multiple hits of espresso (at least the Giardini is dotted with many

little coffee-vendors, who all pour very respectable brews). Fortified with caffeine, I then began the home-stretch of my Giardini pavilion explorations.

And you can’t throw an Art Bash without a Mist Machine:

![]()

Exterior: Finland pavilion. Designed in 1956 by Finland’s greatest architect, Alvar Aalto.

Details of Aalto’s Finland pavilion design:

On the grounds of Finland’s pavilion

Finland: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside the Finland pavilion:

![]()

Exterior: Hungary pavilion. Built in 1909. Architect: Geza Rintel Maroti.

Details of the Hungary pavilion’s exterior:

Hungary: Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Inside the Hungary pavilion:

![]()

My day’s work nearly finished, I ambled back across the Giardini, and towards the exit.

P5092522 I thought I might give the Switzerland pavilion another try, but found that their press conference was still pending. However…the folks outside seemed not to care: bowls of champagne awaited them…all was Right in their World.

![]()

By mid-afternoon, the weather had become beautiful. I stuffed all of the Show-Literature

I’d collected into my backpack, and began to linger on the Riva dei Partigiani…

Contented as a Clam.

I hopped onto a Vaporetto, and stood next to a talkative artist who had

turned himself into a walking protest sign. His gripe: the Biennale’s “arrogant” Curator,

Ralph Rugoff.

I disembarked at Vallaresso-San Marco, and then took another water bus, across

The Grand Canal, to my final stop, at Campo della Salute.

The dock, at Salute, is just a 2 minute walk away from the Centurion Palace Hotel.

I passed the Basilica of Santa Maria della Salute, where, during several afternoons later in my Venice-stay, I’d sit for hours, listening to wonderful, free-to-all choral and organ concerts.

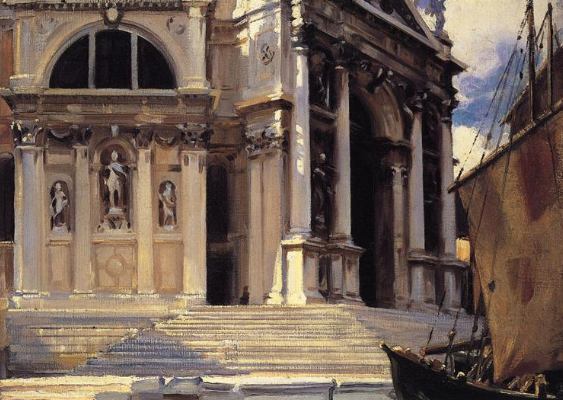

John Singer Sargent made this painting of the Basilica of Salute,

in 1913.

From Fondamente Salute, I crossed this little bridge…

…which leads through the tunnel of Calle del Bastion….

….which delivered me back to the tranquility of the Centurion Palace Hotel.

I knew I’d need to sleep long & well that night, because tomorrow I’d have another full day of

Biennale-looking: this time at the Arsenale!

Aerial view of my favorite corner of Venice.

Copyright 2019. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

3 Responses to Venice: BIENNALE ARTE 2019. Part One