We’re about to begin exploring La Biennale’s exhibits in the Arsenale portion of the Show. This is my view (on the morning of May 10, 2019) of the Darsena Grande: a huge, enclosed docking basin which is in the center of the Arsenale complex.

Of La Biennale’s two permanent venues, I’ve always preferred the Arsenale over the Giardini. The enormous breadth of the Arsenale’s man-made harbor and its lengths of canal-side walkways ( fondamente ), along with the sheer magnitude of its factory buildings, are stunning reminders that humankind’s industriousness can indeed function within man-made settings of incredible ingenuity and beauty. With or without the presence of La Biennale, Venice’s Arsenale is a Wondrous Sight.

For Arsenale-history-and-architecture-buffs, the only way to get inside this complex is to attend a Biennale…be it for the Art Shows which are mounted in odd-numbered-years, or for the Architecture Shows which occur in even-numbered-years. Consistent with my policy of NOT rephrasing already-written historical summaries, here’s a snippet from Wikipedia:

“The Venetian Arsenal ( Italian: Arsenale di Venezia ) is a complex of former shipyards and armories. Owned by the state, the Arsenal was responsible for the bulk of the Venetian republic’s naval power during the middle part of the second millennium. It was ‘one of the earliest large-scale industrial enterprises in history.’ “

“Construction of the Arsenal begin around 1104, during Venice’s republican era. It became the largest industrial complex in Europe before the Industrial Revolution, spanning an area of about 110 acres, or about 15 percent of Venice. Surrounded by a 2-mile rampart, laborers and shipbuilders regularly worked within the Arsenal, building ships that sailed from the city’s port. With high walls shielding the Arsenal from public view and guards protecting its perimeter, different areas of the Arsenal each produced a particular prefabricated ship part or other maritime implement, such as munitions, rope, and rigging. These parts could then be assembled into a ship in as little as one day. An exclusive forest owned by the Arsenal navy, in the Montello hills area of Veneto, provided the Arsenal’s wood supply.”

Aerial View: Arsenale, Venice

Learning this, how could you NOT be excited about the prospect of spending a day

within the once-secret confines of the Arsenale? And, for their own reasons, the Travel Gods decided to smile upon me: the weather on May 10, 2019 — my second Press Day of La Biennale’s Pre-Opening — was Perfect: sunny, seasonably warm, and breezy (the five remaining days of my stay in Venice then reverted to the abysmal, cold, stormy, May-Cember conditions which had first greeted me, on May 8th).

As with Part One of my Biennale tour, I’ll mostly allow my photos to speak for themselves. However, as I did in Part One, before I give you the opportunity to be submerged into (or perhaps be overwhelmed by?)

a wealth of images of La Biennale’s Arsenale venue, I will highlight worthwhile OFFSITE art shows which will be open through most of November, when the Official Biennale also closes.

![]()

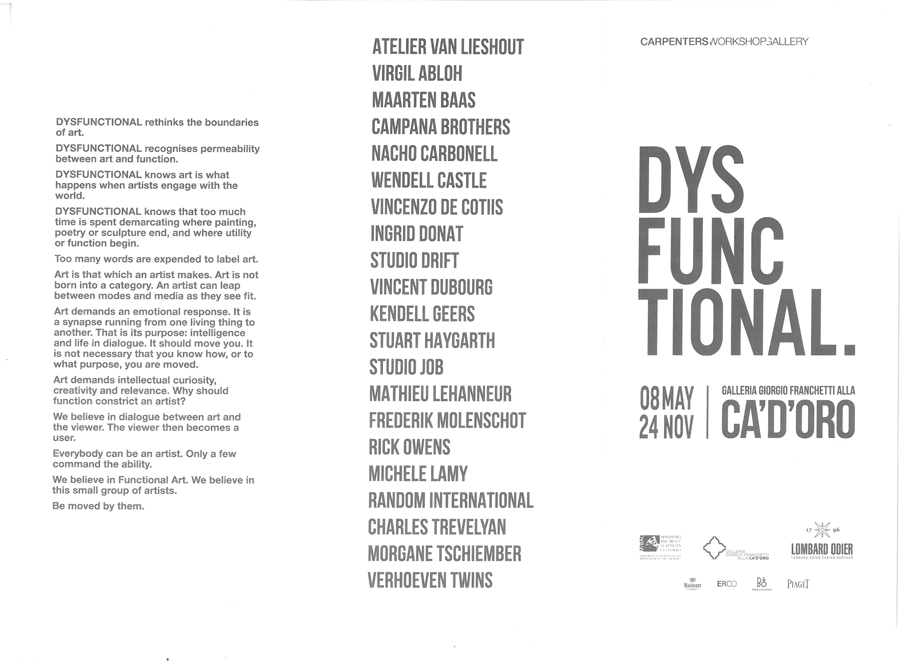

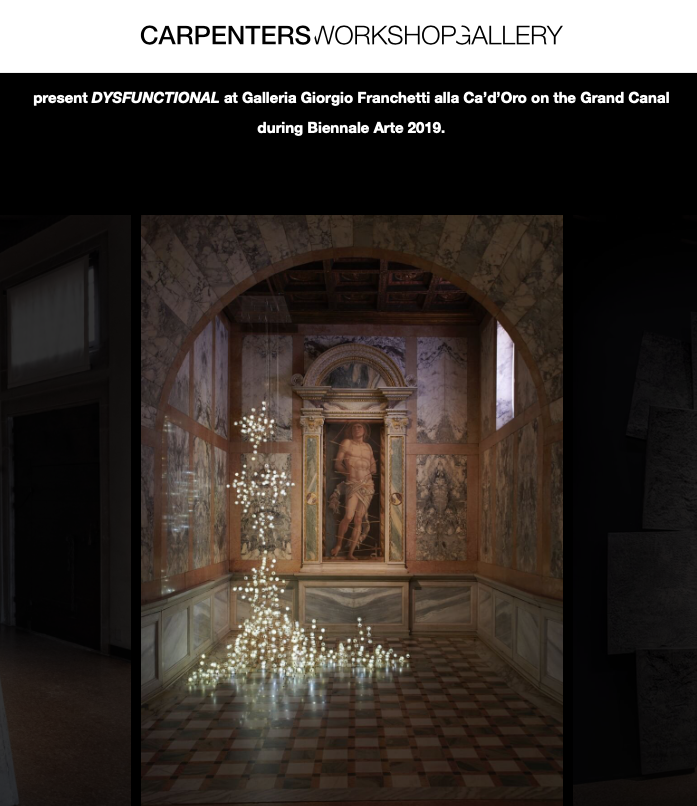

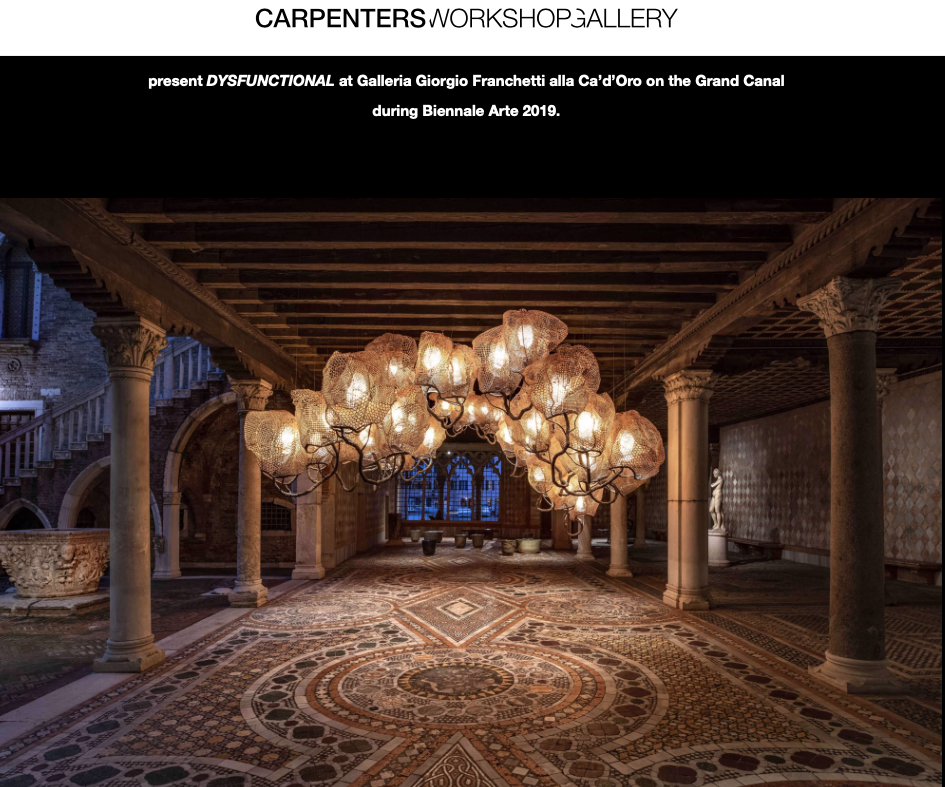

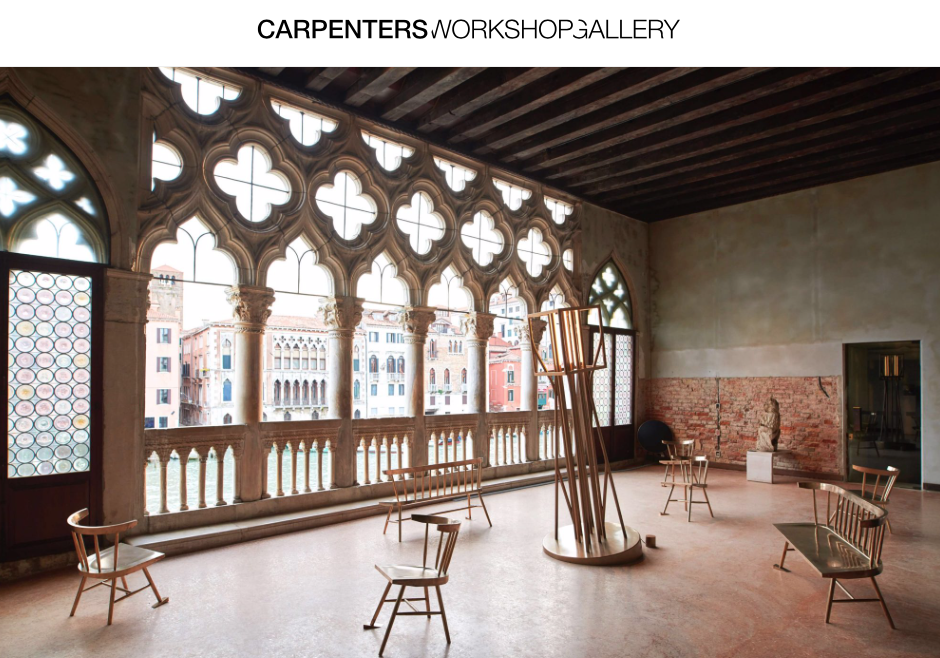

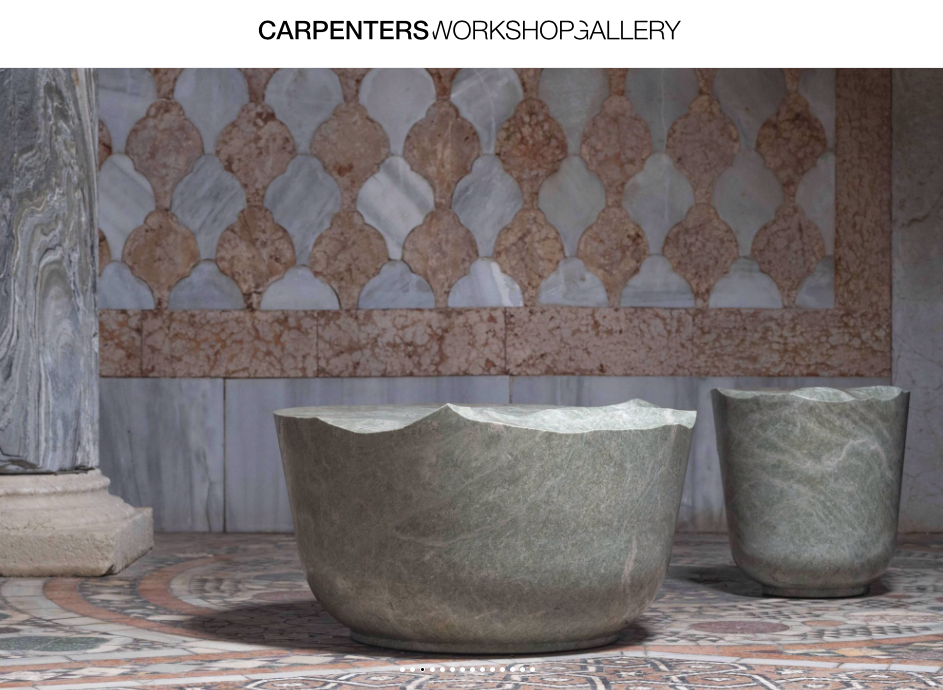

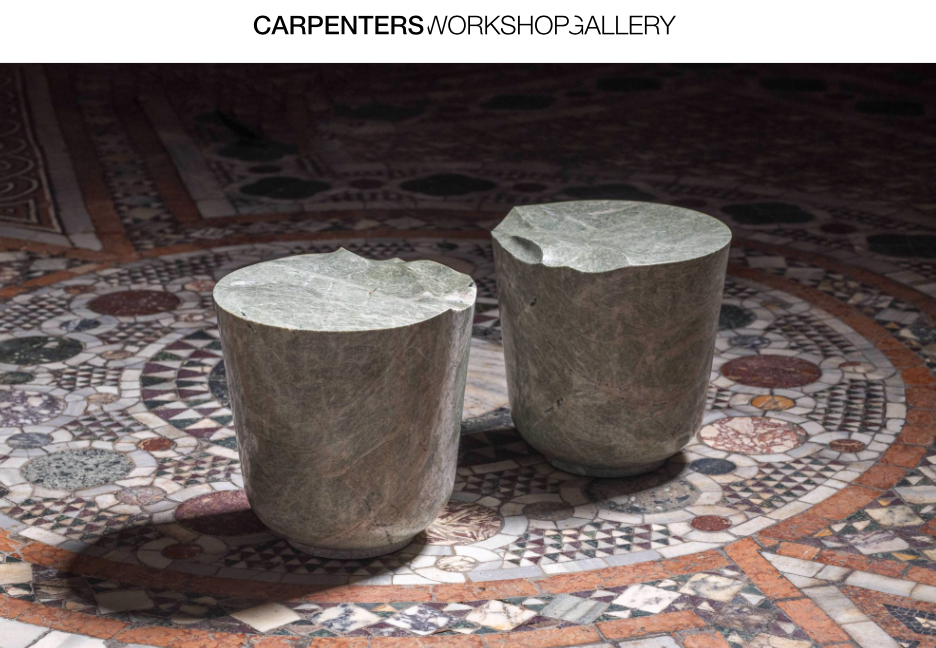

Offsite Show #1, NOT to be missed! DYSFUNCTIONAL, by the Carpenters Workshop Gallery, at Ca’ d’Oro … which is one of Venice’s most fabulous palazzo-museums. DYSFUNCTIONAL will be displayed until Nov. 24, 2019.

Galleria Giorgio Franchetti Alla Ca’ d’Oro. Cannaregio.

Entrance on Strada Nuova, which leads directly to the nearby Vaporetto

boat dock, on the Number 1 Line—ACTV: Ca’ d’Oro stop.

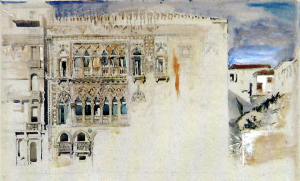

Waterfront façade of Ca’ d’Oro, on the Grand Canal. Built in 1430, this is the best surviving palazzo in the Venetian-Gothic style. The exterior was once adorned with gilt: thus the locals named the palazzo a “golden house.” Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

Watercolor Sketch of Ca’ d’Oro, done by John Ruskin in 1845

DYSFUNCTIONAL is neither a Biennale Exhibit nor a Biennale Collateral Event. But when La Biennale blows into town, it’s as if the Art-Clouds over the entire Lagoon have been seeded, and art rains down, all around the City. During my hours spent at this exhibit, I refrained from taking pictures. The opulently-decorated interiors and the treasure-trove of permanently-mounted art there (collected by the palazzo’s last owner, baron

Giorgio Franchetti, who bought the building in 1894, and bequeathed the palace and its contents to the Italian state in 1916), juxtaposed with the surprising creations of the Carpenters Workshop Gallery, were magical: I didn’t want to be separated from what I was seeing…not even by the lens of my normally-in-constant-use Camera.

Per their members, the “Carpenters Workshop Gallery produces and exhibits functional sculptures by international rising and already established artists and designers going outside their traditional territories of expression.”

With ateliers in London, Paris, Manhattan, Roissy and San Francisco, this group produces work that combines the best of craftsmanship and fine art: always displayed in ways which are sensitively-tuned to specific environments.

Show Brochure/Front side.

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

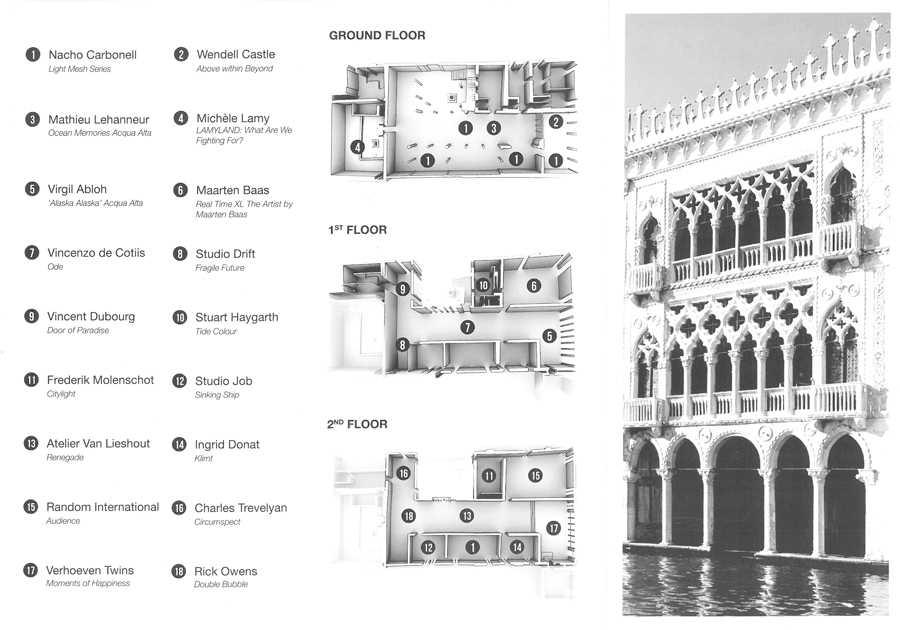

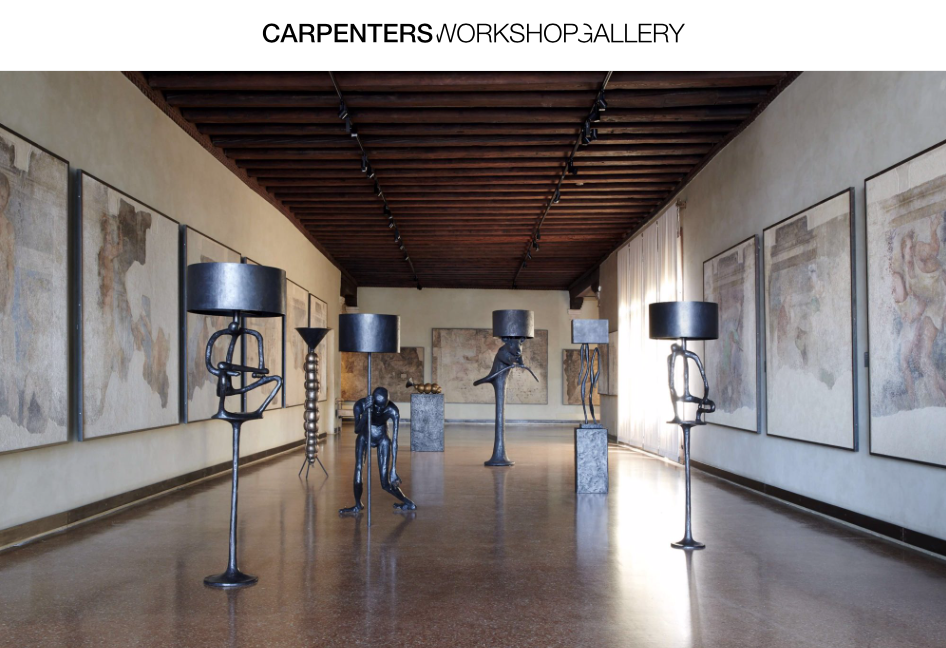

Show Brochure/Flip side.

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

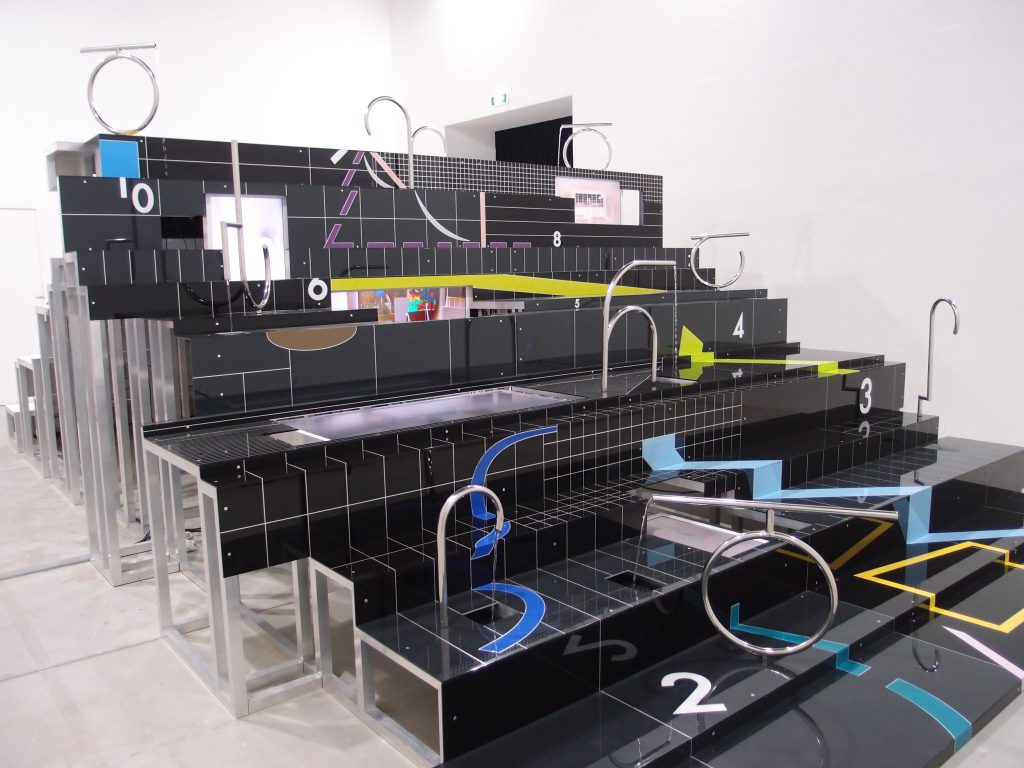

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

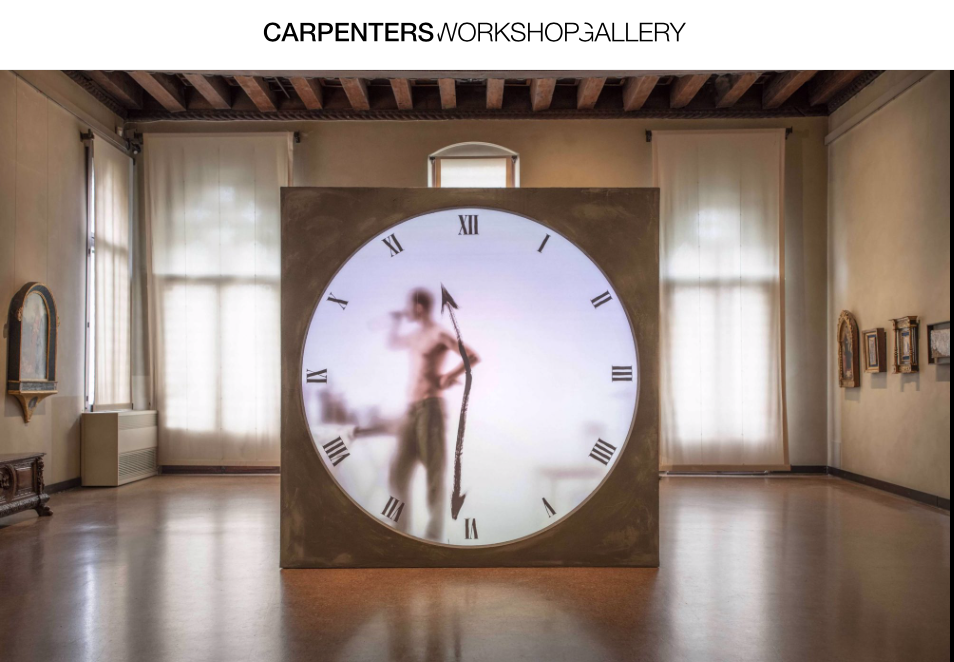

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

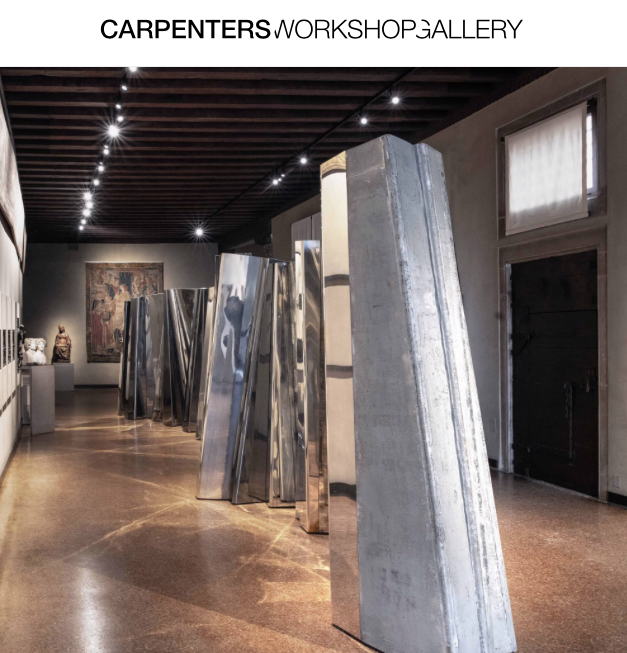

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

Image courtesy of Carpenters Workshop Gallery

![]()

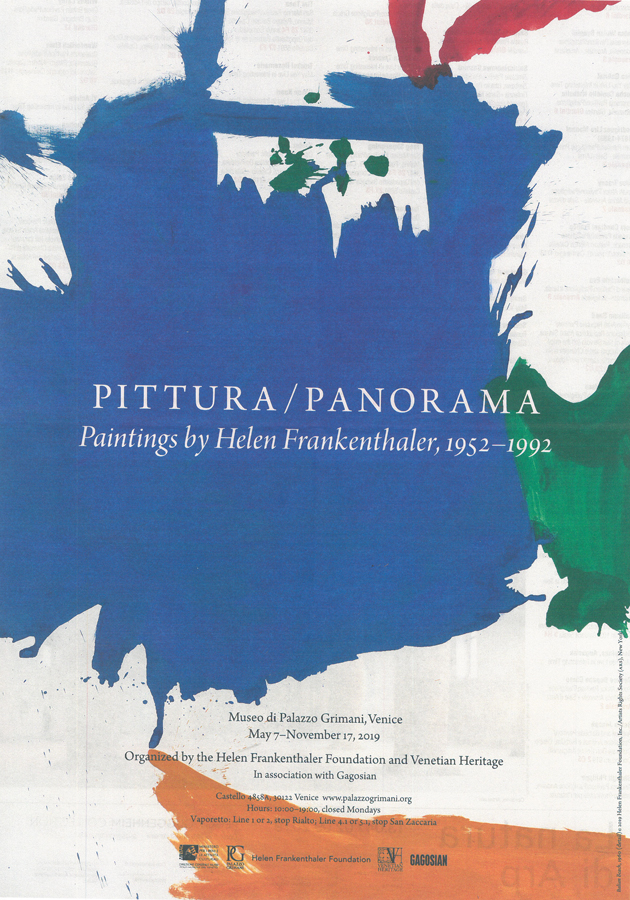

Offsite Show #2, NOT to be missed if you’re curious about the gorgeous paintings of the

great 20th century American artist, Helen Frankenthaler.

PITTURA/PANORAMA: Paintings by Helen Frankenthaler, 1952—1992.

Show open until Nov.17, 2019

Museo di Palazzo Grimani, Ramo Grimani, Castello.

To find Palazzo Grimani, grab a street map and, from Piazza San Marco, start walking northeast, into the heart of Castello; the Museum is

at the intersection of the Rios San Severo and Santa Maria Formosa.

The easy-to-miss Entrance to Palazzo Grimani. Image courtesy of Wikipedia

The Museo di Palazzo Grimani is an ancient palace, which, at the

beginning of the 16th century, was substantially remodeled by architects

Jacopo Sansovino & Andrea Palladio, who gave the exterior a classical stamp.

Later, the interiors were redone by Mannerist artists.

I’d never heard of this Museum … and it’s challenging to find: it’s buried within a maze

of alleys, near to the border between the Castello and San Marco neighborhoods.

This poster, mounted at my Salute Vaporetto dock, first made me aware of

the Frankenthaler Show.

Image courtesy of The Art Newspaper

Although the Frankenthaler Show at Palazzo Grimani is not officially affiliated with this year’s Biennale, the timing of the Show is intentional and fitting. During Venice’s Biennale of 1966, Helen Frankenthaler, along with 3 other painters, represented the United States at its Pavilion in the Giardini. With 2019’s Exhibit at Palazzo Grimani, Frankenthaler’s work returns to Venice, after a 53-year-long absence.

My interest in Frankenthaler, who is under-represented in the collections of major

American museums, is both aesthetic and sentimental. When still quite young, I was introduced to Frankenthaler’s art by my maternal aunt, artist Audrey Syverson Sochor. As a teenager, I lived for a time in the San Francisco Bay area with Audrey and

her Shakespearian-scholar husband, Arthur Vernon Sochor (who I lovingly called my

“Nuncle,” as the Bard would have done). Audrey began her art-career as a UC Berkeley-trained, abstract expressionist painter, she evolved into a stage set designer, and, at age 77, her work came to fruition with the debut of her conceptual, painted fabric installations, called “Sea Curtains.” When I was 17, Audrey would drag me to art-openings at the gallery that represented her, on Maiden Lane, in San Francisco. Her gallery was located across the Lane from this building, which was designed by Frank Lloyd Wright…

San Francisco’s Morris Gift Shop. Built by Frank Lloyd Wright in 1948. Inside, the compact space is hollowed out

by a circular ramp, one which was used as a physical prototype for the huge ramp which

Wright would eventually build inside the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, in Manhattan.

Image courtesy of Wikipedia.

…so merely being in the vicinity of this architectural gem always thrilled me.

At my Aunt’s art-unveilings, I was usually the only “kid” in the room, and a couple of things were constants:

*Mustachioed, shockingly-ancient Berkeley professors wearing black capes would swoop over to me and ask: “don’t I know you?” I’d smile, say “no,” and vanish into the crowd.

*Less-predatory gallery-goers would inevitably observe: “you know, your Aunt’s work reminds me of Frankenthaler,” I’d reply: “It does, yes … she’s pouring paint onto raw canvas, too. But whereas Frankenthaler’s stuff is all about myth and landscape, Audrey’s is more about…?” I’d shrug, and stop before saying “sex” ( I was in a Fast Crowd, but remained a Proper Girl ) … but we all knew what we were looking at.

My teenage years, though turbulent, were memorable (but not times one would wish to repeat). I always admired my Aunt’s technical brilliance and candid illustrations of her passions, but I preferred Frankenthaler’s pictures, which were permeated with her references to history, literature, and philosophy. Because of the deeply textured nature of her work, Frankenthaler’s paintings, although constructed of canvas and pigment, invite the Alert Viewer into a multidisciplinary experience. Frankenthaler’s techniques

and foci of attention continually evolved, but she returned, over and again, to the grand context of landscape painting. And so, a half-century later in Venice, to stumble upon this show of 14 large-scale Frankenthaler canvases which were done over a span of 40 years became for me an unexpectedly emotional event as it dredged up ancient memories of my Aunt, who had introduced me to Frankenthaler’s work, and who in countless other ways had broadened my cultural horizons. Audrey, though odd and somewhat tetchy, was crazy like a fox. Prior to one of these gallery events, I remember sitting with her at the original Swenson’s Ice Cream shop, near Union Square. Between bites of a sundae, and apropos of nothing, she looked at me and declared: “Nan, someday you’ll be a Writer!” I thought she was daft.

My Aunt, Audrey Sochor: still tilting at windmills and looking youthful, at age 88, when this photo was taken.

Audrey Sochor: Born 1923, Died 2014.

But here’s why I most value this show now in Venice: although I’d been generally aware of Frankenthaler’s oeuvre, many of these large-scale canvases were new to me. If you love an artist, there’s no substitute for standing nose-to-nose with her powerful painting: no thumbnail image in a glossy catalogue can begin to replicate the excitement of being personally confronted by a picture that almost vibrates with the energies of the long-dead soul who painted it.

At the entrance to the Show at Palazzo Grimani: two photos of Helen Frankenthaler, at work. Helen Frankenthaler: Born 1928, Died 2011.

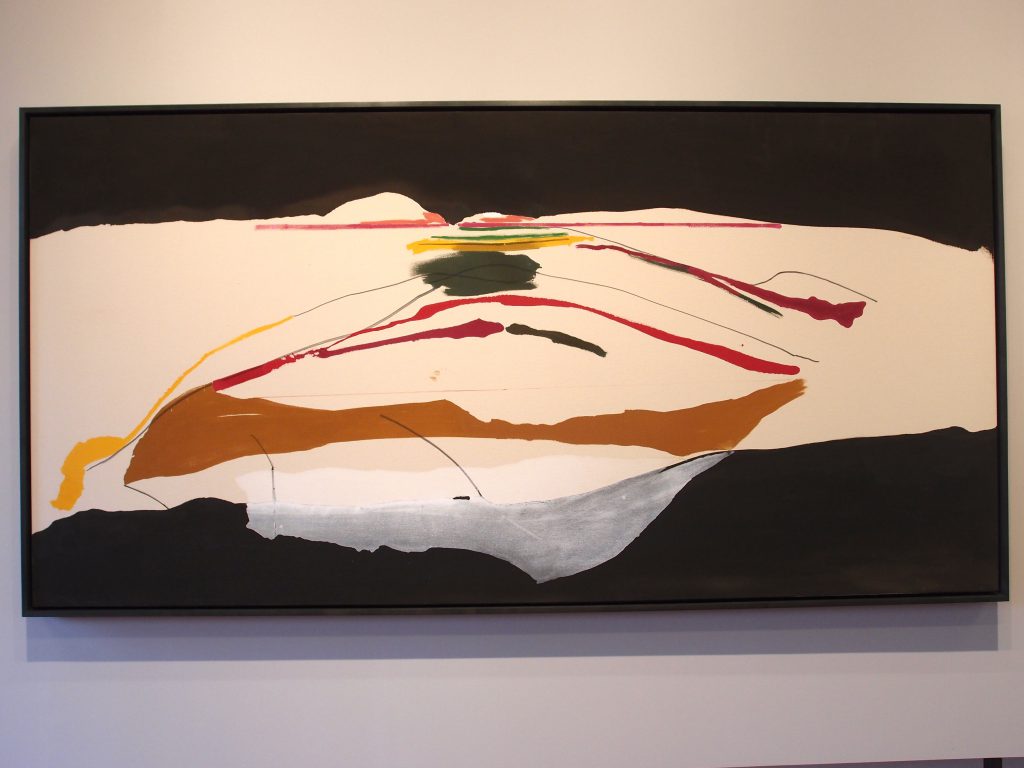

“Open Wall” 1953. Oil on unsized, unprimed canvas.

“10/29/52” 1952. Oil on unsized, unprimed canvas. 64-7/8 inches x 66-¼ inches.

View of one of the Gallery rooms, at Palazzo Grimani’s Frankenthaler Show.

“Riverhead” 1963. Acrylic on canvas. Gallery Notes: “This is one of Frankenthaler’s first canvases entirely filled with sumptuous, loosely painted color. The work’s implications of landscape are overt.”

“For E.M.” 1981. Acrylic on canvas. 71-1/4 inches x 115-1/4 inches. Gallery Notes: “Almost 2 decades after painting Riverhead, Frankenthaler richly amplified both its painterliness and its associations with landscape—although she actually based the composition on a still life of a fish by Edouard Manet.”

“Italian Beach” 1960. Oil on sized, primed linen. Gallery Notes: “In the early 1960s,

Frankenthaler tended to let flatness dominate her painting. This canvas was painted in Alassio, Italy. Abbreviations for a hilltop, a band of foliage, and an expanse of sand bridge the space from a pool of sea blue in the left half of the canvas to the work’s right edge.”

“New Paths” 1973. Acrylic and marker on canvas.

Gallery Notes: “New Paths has a graphic quality recalling Italian Beach, but it is softer in feeling, being painted on raw canvas. Its flat, schematic marking is also combined with a new, inventive manner of opening up pictorial space: Frankenthaler graded the narrow ribbons that span the light central channel so that they diminish in size from bottom to top, making that area of the panoramic canvas appear to recede. As they reach the top of this light zone, they turn into a cluster of narrow horizontals, seeming distant from the broader, irregular ribbons at the base.”

“Barometer” 1992. Acrylic on canvas. 54-1/4 inches x 69-1/2 inches. Gallery Notes: “Although celebrated as a colorist, Frankenthaler periodically made paintings restricted to ranges of lights and darks.

Here, she reengaged with the kind of tonal underpainting used by the old masters to create a

spontaneously finished composition.”

“Overture” 1992. Acrylic on canvas. 70 x 94 inches. Gallery Notes: “In the early 1990s, Frankenthaler reprised the painterliness of earlier works but filled it out more dramatically than before. Here, she used thick as well as thin paint, which she moved across the surface with sponges, scrapers, and combs to create the work’s turbulent effect.”

“Brother Angel” 1983. Acrylic on canvas. Gallery Notes: “In the early-to-mid

1980s, Frankenthaler enhanced the spatiality of her canvases by applying loosely applied grounds of a single, atmospheric color. This is a rare case of her doing so with glowing gold

paint, on which is superimposed a scatter of dabs, dots and dashes of more tangible pigment.”

“Madrid” 1984. Acrylic on canvas. Gallery Notes: “For Frankenthaler, color didn’t always have to be vivid. Here she used a range of light browns, recalling old master paintings, as the setting for quiet, floating zones of green, gray, dark brown, and orange supported by

simple calligraphic drawing.”

“Window Shade No.2” 1952. Oil & canvas mounted on board. Gallery Notes:

“Frankenthaler’s first experience of large horizontal paintings made by contemporary artists was in 1950, when, as a 21-year old not long out of college, she saw abstract compositions by

Jackson Pollock involving looping skeins of poured paint. In this earliest canvas in the

Exhibition, she tried something similar on a smaller scale.”

“Pink Bird Figure” 1961. Oil on unsized, unprimed canvas. Gallery Notes:

“By 1961, Frankenthaler had long abandoned Pollock’s looping skeins of paint to work with open, expansive drawing. Here, the flattened image of a pink bird spreads laterally over a flight

path inscribed across the full width of the horizontal painting.”

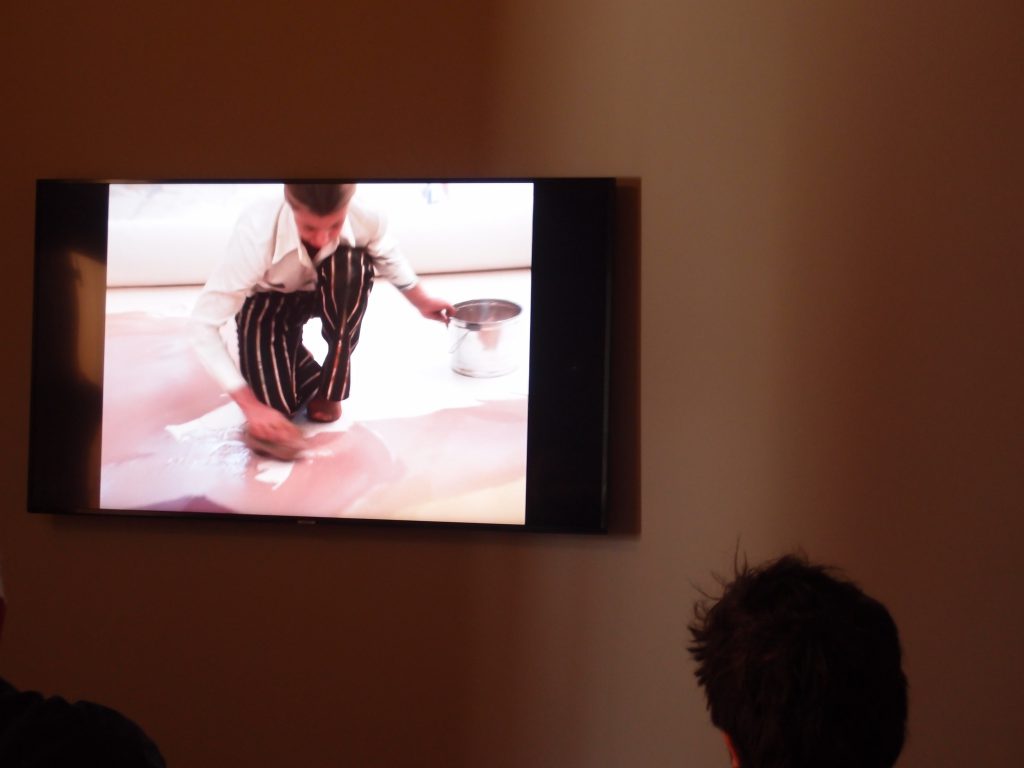

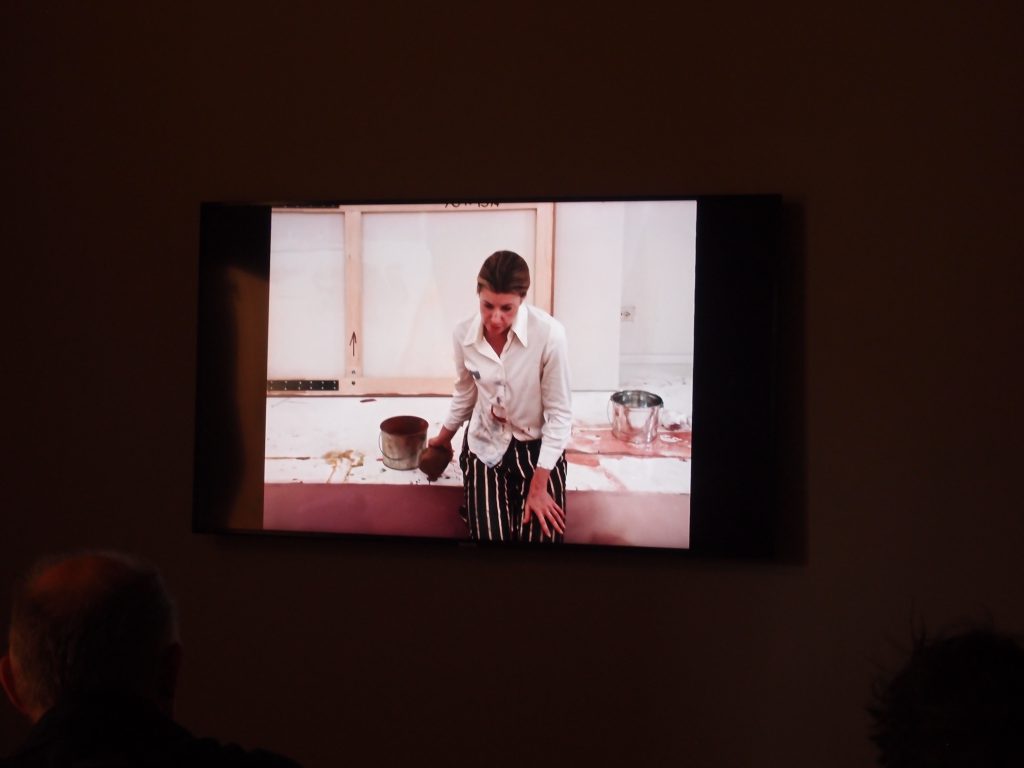

The Palazzo Grimani show is also presenting a film showing Helen Frankenthaler at work in her studio. Here are some stills from that film. And check out

her Snazzy Outfit! Paint splotches and all, this was One Stylish Lady.

A Jolly Frankenthaler, at work in 1964. Screen Shot, courtesy of the website of the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation.

Helen Frankenthaler’s art is both refined and sensuous: I consider her work to be that of an intellectual voluptuary. The Palazzo Grimani show, which illustrates her ever-changing techniques, as revealed in these large-scale landscapes, displays just a fraction of her prodigious artistic output. In 2017, the Helen Frankenthaler Foundation embarked upon the long-term project of assembling a catalogue raisonne, which will encompass ALL of Frankenthaler’s works, in many mediums. I look forward to the day when that definitive List will be completed.

![]()

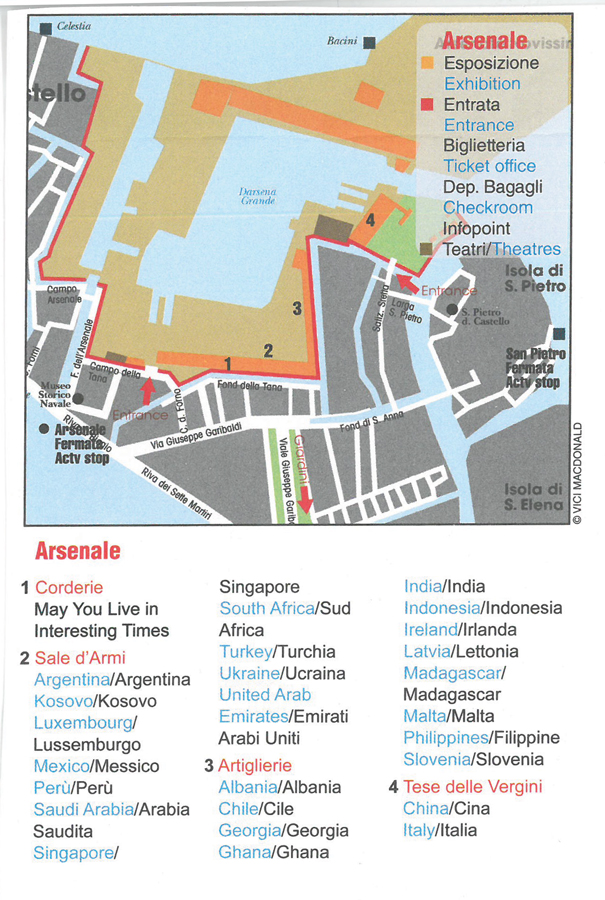

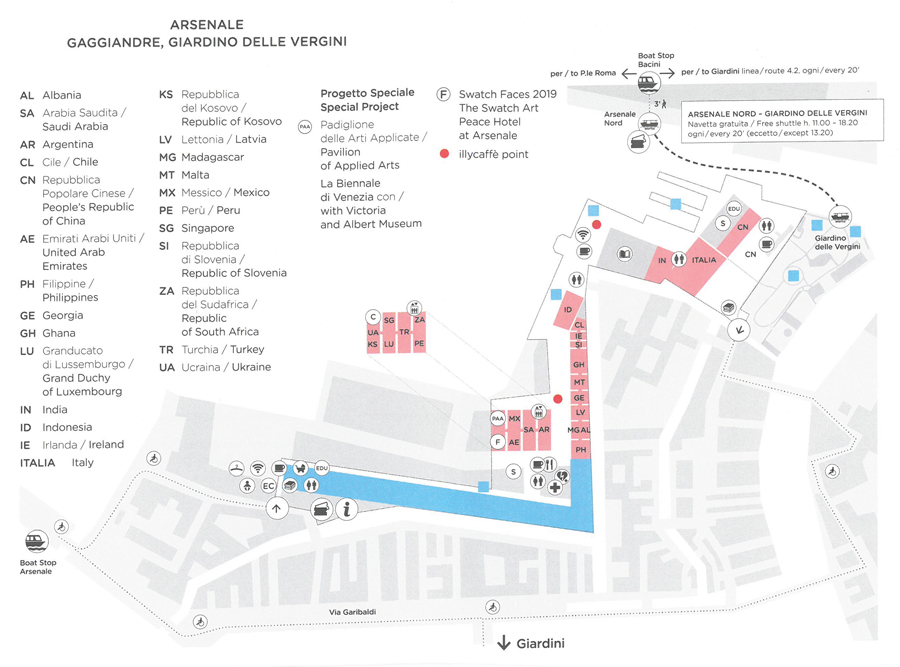

Let us now begin our explorations of the Arsenale. Because I must have been a map-maker in another life, I’m compelled to inflict upon you a little tutorial about the lay of the land (and water). Once you’ve gotten your bearings, my photo-DIARY of the Show will then unfold in a sequence that mimics my day of wandering through this marvelous venue.

Map: Overview of Biennale’s exhibition areas, in the Arsenale

La Biennale occupies only a portion of the Arsenale’s 110 acres. The Show sprawls across four sections of the complex; these buildings lie to the south and east of the man-made harbor of Darsena Grande.

First, some birds-eye views of the central part of Arsenale:

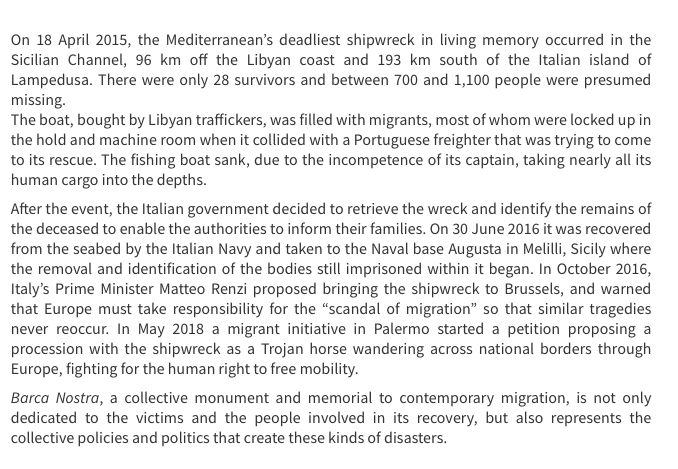

We’re looking south, over the Darsena Grande. The Adriatic Sea is on the far horizon. The towering Armstrong Mitchell Crane is perched upon the eastern edge of the Darsena Grande. At left/front, the two long, enclosed buildings are where the Chinese and Italian pavilions of Biennale always set up shop. The pair of arched, open-air structures in center & right of this photo are the Gaggiandre: these roofed docks were constructed between 1568 and 1573. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Another view over the Darsena Grande; this time we’re looking south-east. Image courtesy of VelaSPA

A broader view, over the Arsenale. We’re looking west. In the central foreground is Arsenale’s walled garden: Giardinio delle Vergini. On the right-hand side of this photo is the northern leg of the Arsenale complex. Behind that: Venice’s North Lagoon. Image courtesy of VelaSPA

![]()

Arsenale’s four Biennale exhibition zones are #1: Corderie, #2 Sale d’Armi,

#3 Artiglierie, #4 Tese delle Vergini.

The following Empty-Buildings-Before-Biennale photos will give you an inkling of what a mammoth undertaking it is, to fill those spaces with Art, for Showtime!

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Corderie.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Corderie.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Sale d’Armi.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Artiglierie.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Artiglierie.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Gaggiandre.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Just one of the many Outdoor Spaces which become part of Biennale’s Arsenale show.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

Giardino delle Vergini.Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

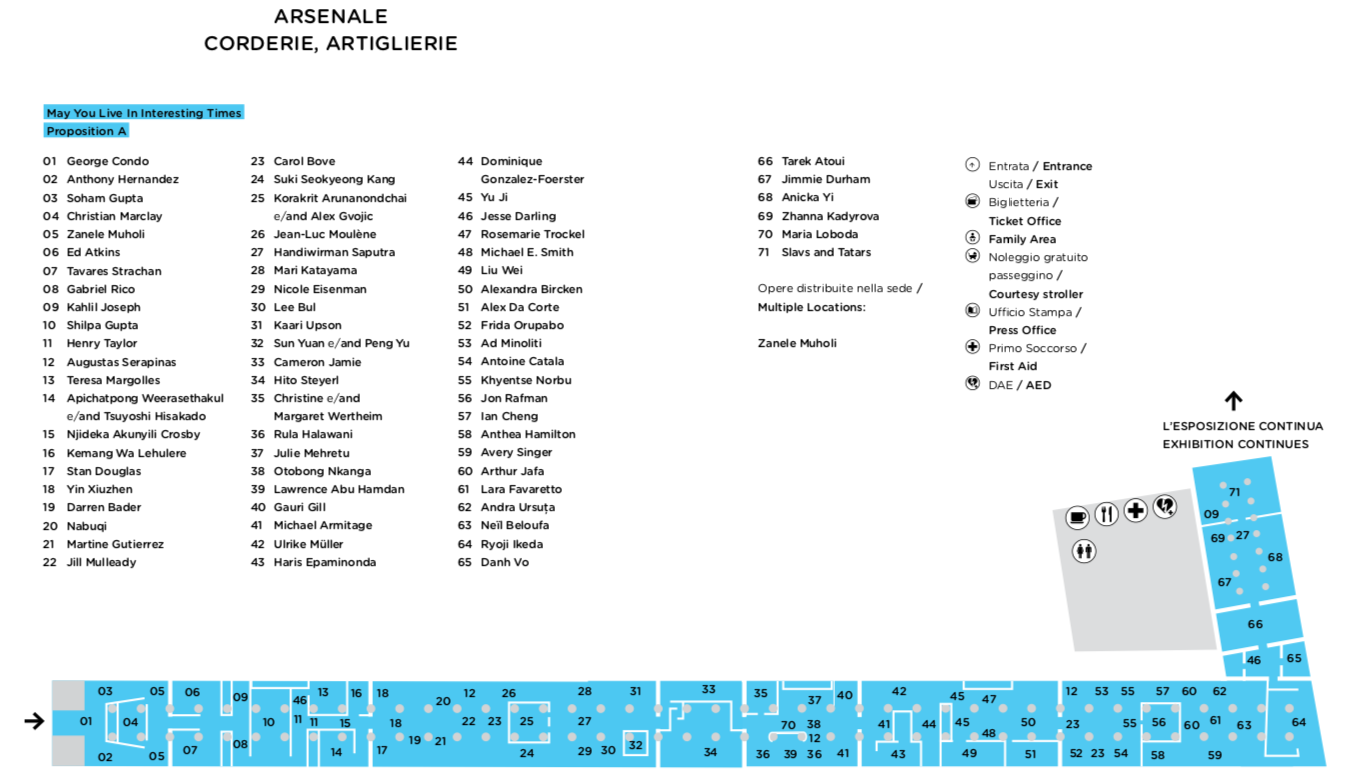

Arsenale: Detailed Map

of Biennale Exhibitors

10AM on May 10, 2019: I’ve just passed through security, and will now sprint down many long alley-ways, towards the distant, northern edge of the Arsenale grounds.

Given my distaste for being in crowds, I’ve learned that, on Press Days, working my way backwards through the Show is always the best strategy. Being among the morning’s first visitors to the End-of-the-Line Exhibits will allow me to enjoy at least a couple of hours of blessedly empty galleries. At a later hour, I’ll collide headlong with the Mob of People who have obediently plotted their paths to proceed from “A” to “Z.” But I like to begin my day at “Z.” I took these photos as I scampered

toward the rear of the Arsenale’s Show grounds.

I’ve turned the corner, at Sale d’Armi. I pause, and look back at the the still-empty Cafe that I’ve just passed.

The other Press-Day visitors have disappeared into the “front” of the Arsenale exhibit spaces. The

Armstrong Mitchell Crane is dead ahead.

The Armstrong Mitchell Crane. Later today, when I pass back this way, you’ll learn more about the Crane.

I’m passing through the Gaggiandre.

The Torre di Porta Nuova is on the north shore of the Accesso Natanti da Porta Nuova;

this wide canal leads to Venice’s North Lagoon. This square tower is where tall masts for sailing ships were built.

Across the canal, six sets of giant, clasped hands rise up, from the north branch of Arsenale. This spectacular construction is artist Lorenzo Quinn’s “Building Bridges.”

“Building Bridges” Artist: Lorenzo Quinn. Aerial view, courtesy of URDesign

Another view of “Building Bridges,” and of the North Lagoon in the distance.

Ever-present Polizia gather near the Giardino’s North-Lagoon-facing Tower

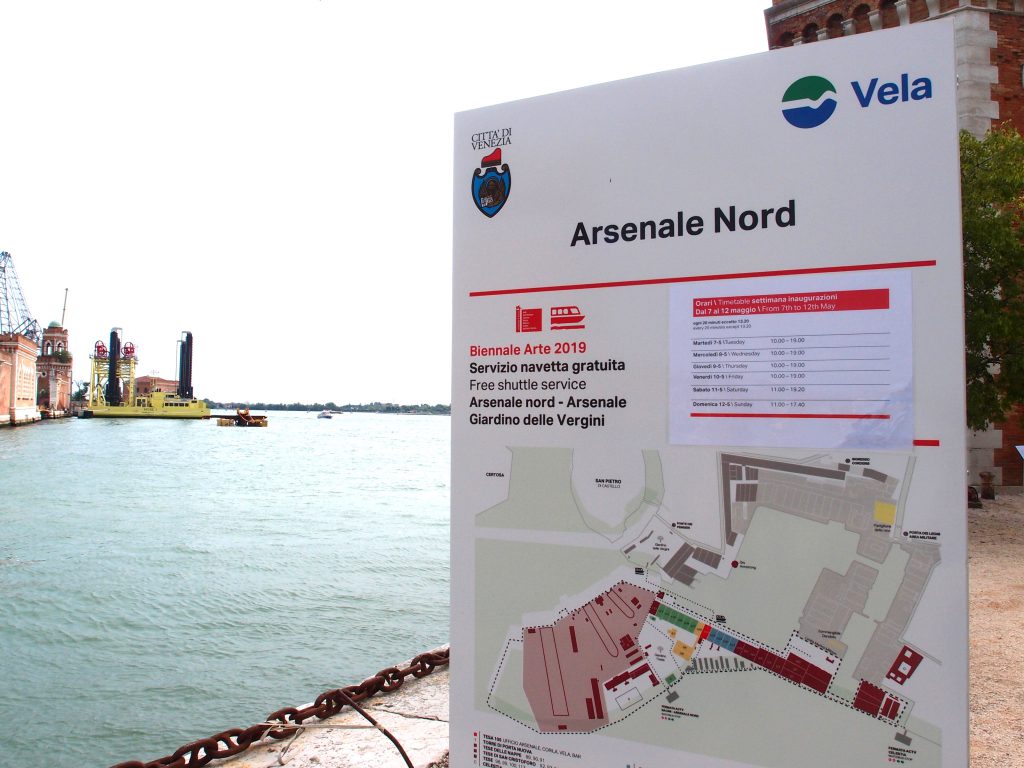

Arsenale Nord Vaporetto Dock—this (not very frequent) service links the south and north sections of Arsenale, and operates only during Biennale.

“Neverland,” by Halil Altindere, of Turkey. in Arsenale’s Giardino

Café outside of the China Pavilion. This coffee-vendor served me a therapeutically-strong espresso.

![]()

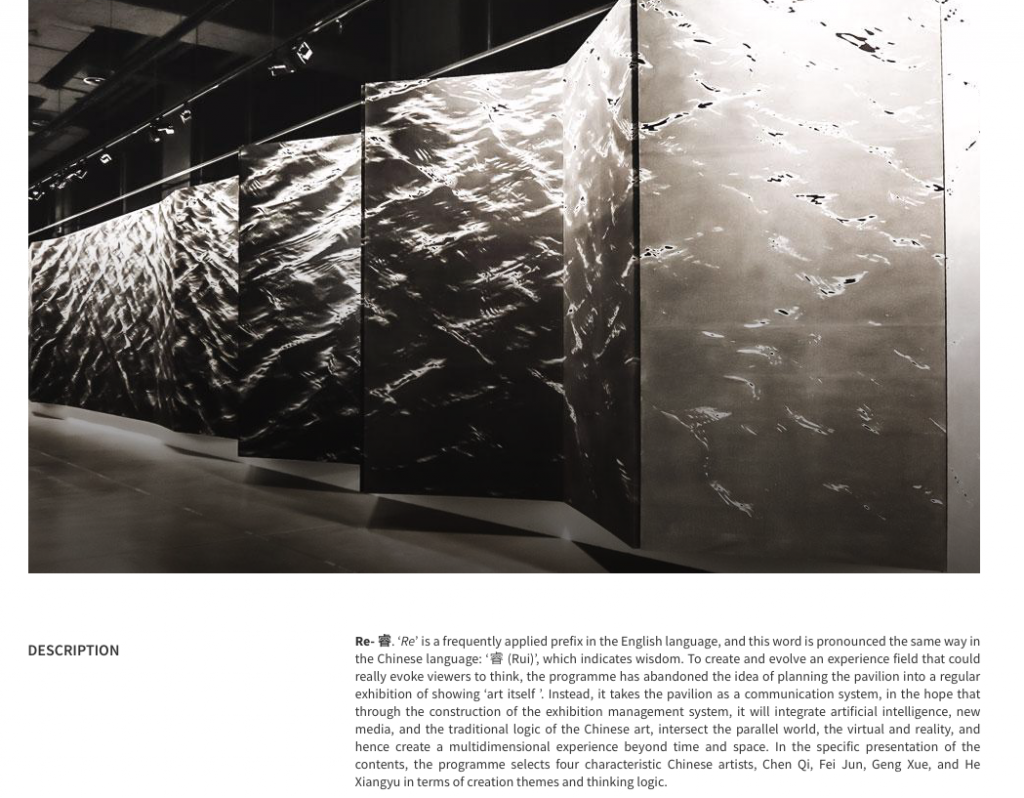

CHINA PAVILION:

The China Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

ITALY PAVILION:

Italy Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

Outside again, to get a brief but necessary dose of fresh air and sunlight!

![]()

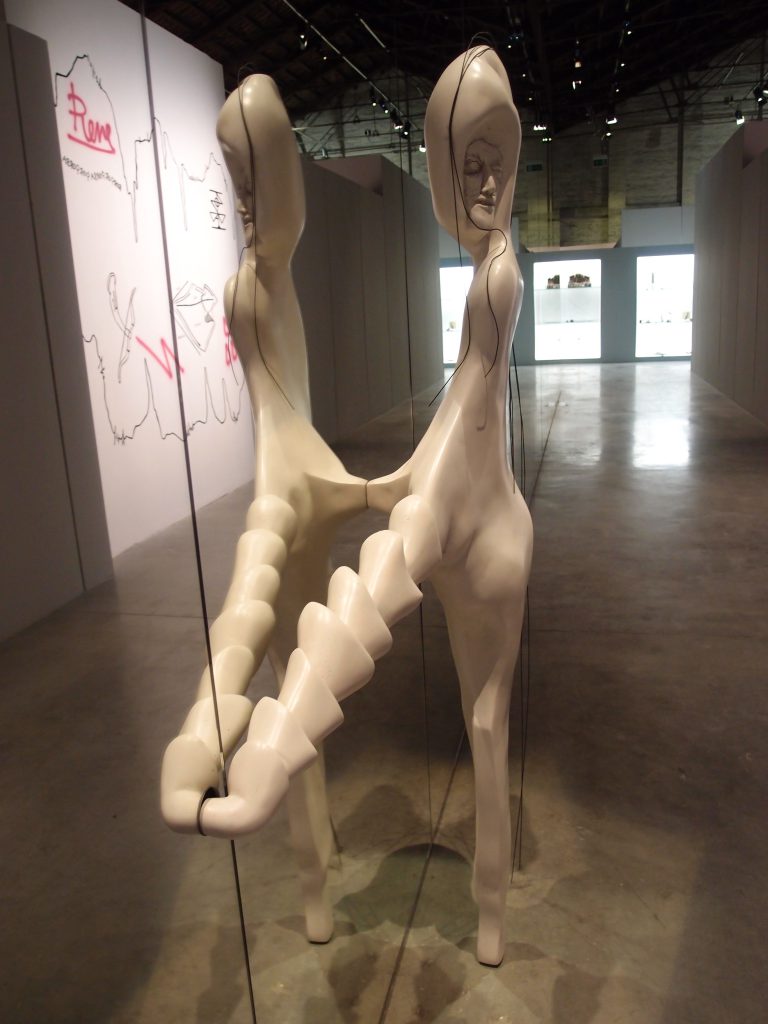

INDIA PAVILION:

India Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

The Arsenale Exhibit buildings aren’t interconnected. Having to

walk outdoors to get to the Artiglierie complex ( which contains eleven more national pavilions ) is a relief: ocean air clears my already over-stimulated brain!

This wonderful metal construction tilts towards the Darsena Grande.

Artist: Ludovica Carbotta.

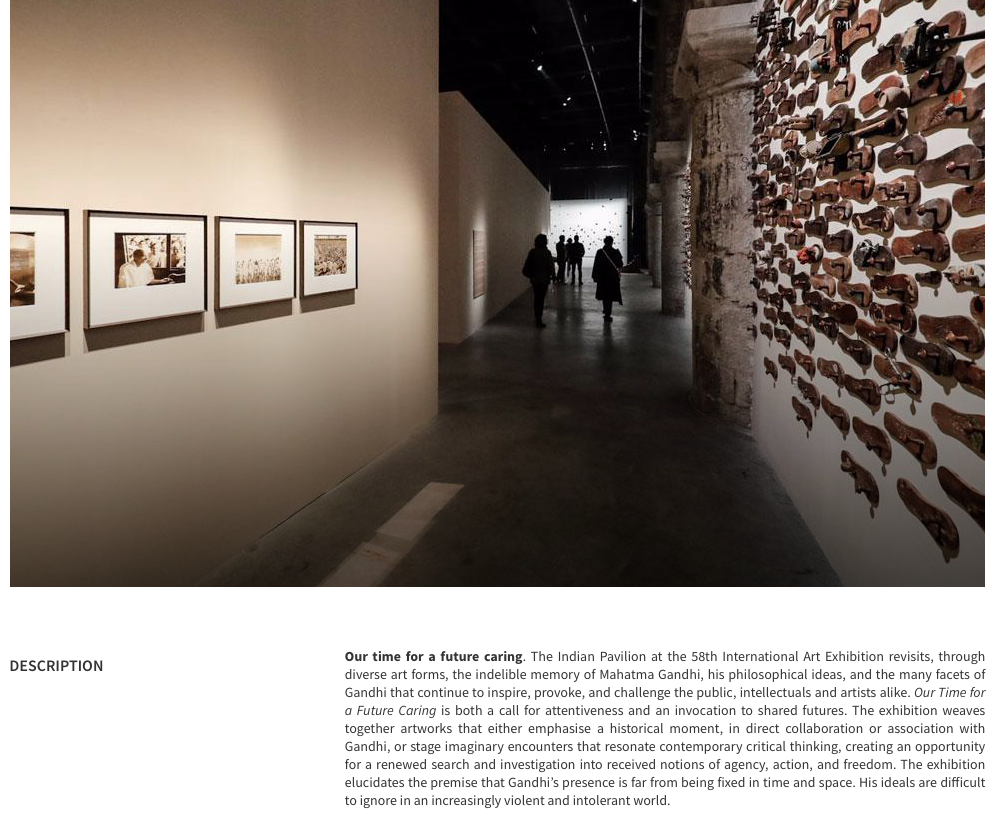

The Armstrong Mitchell Crane

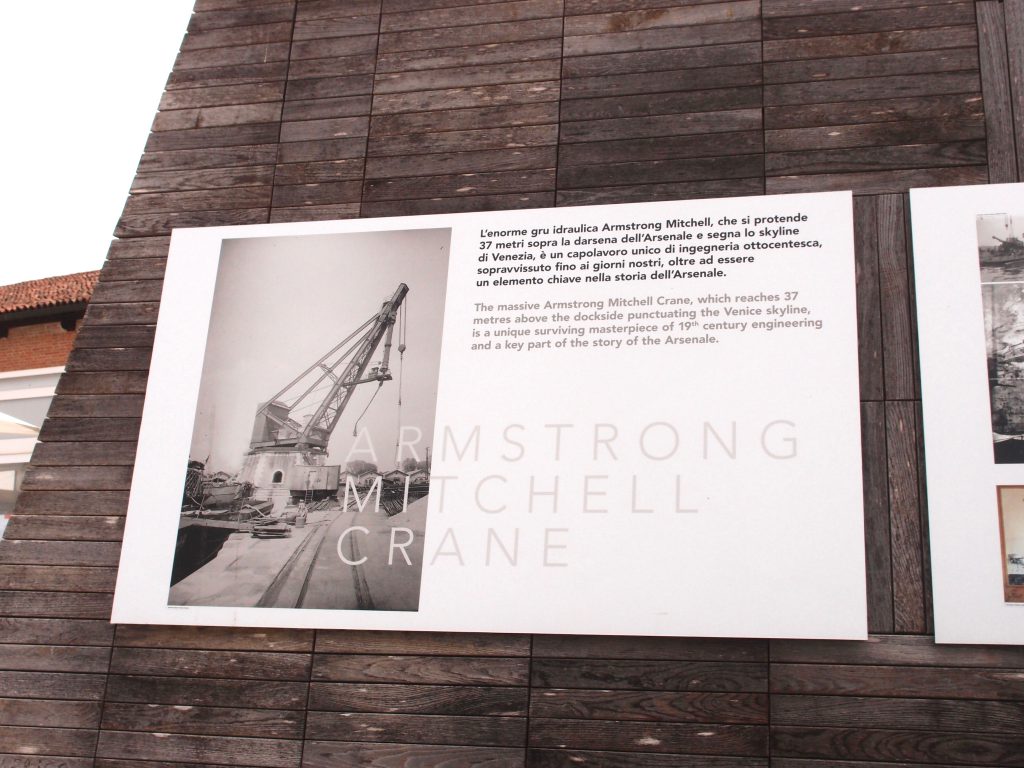

“Barca Nostra.”

Salvaged refugee boat.

History of the “Barca Nostra.” Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

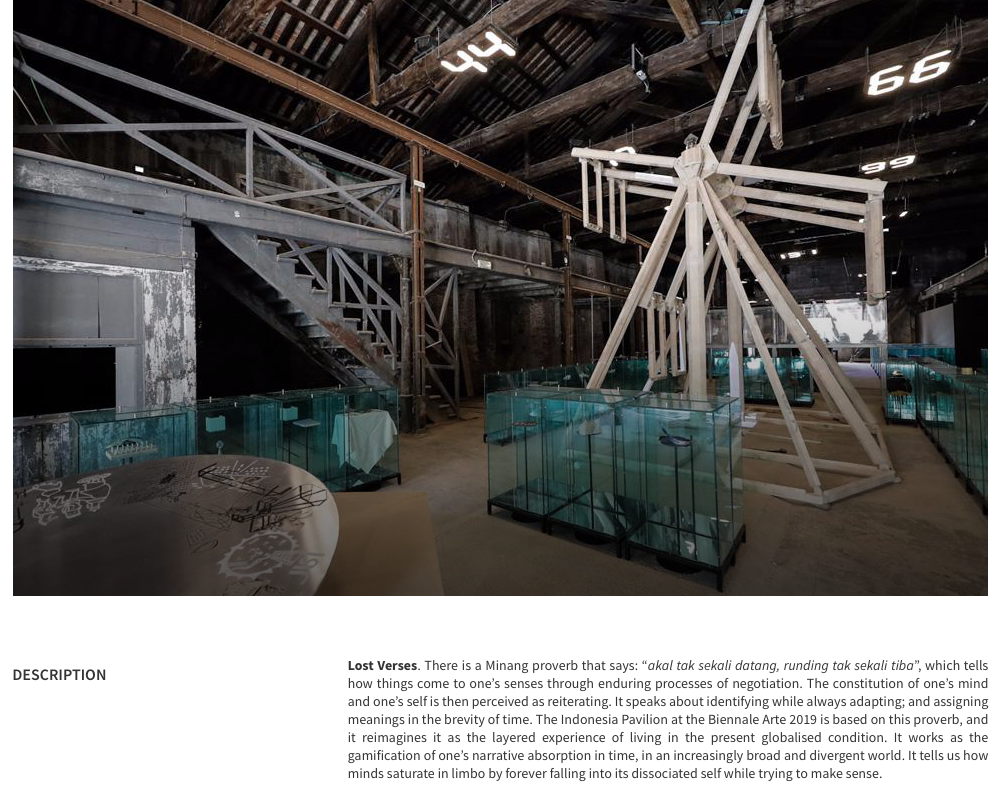

INDONESIA PAVILION:

Indonesia Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

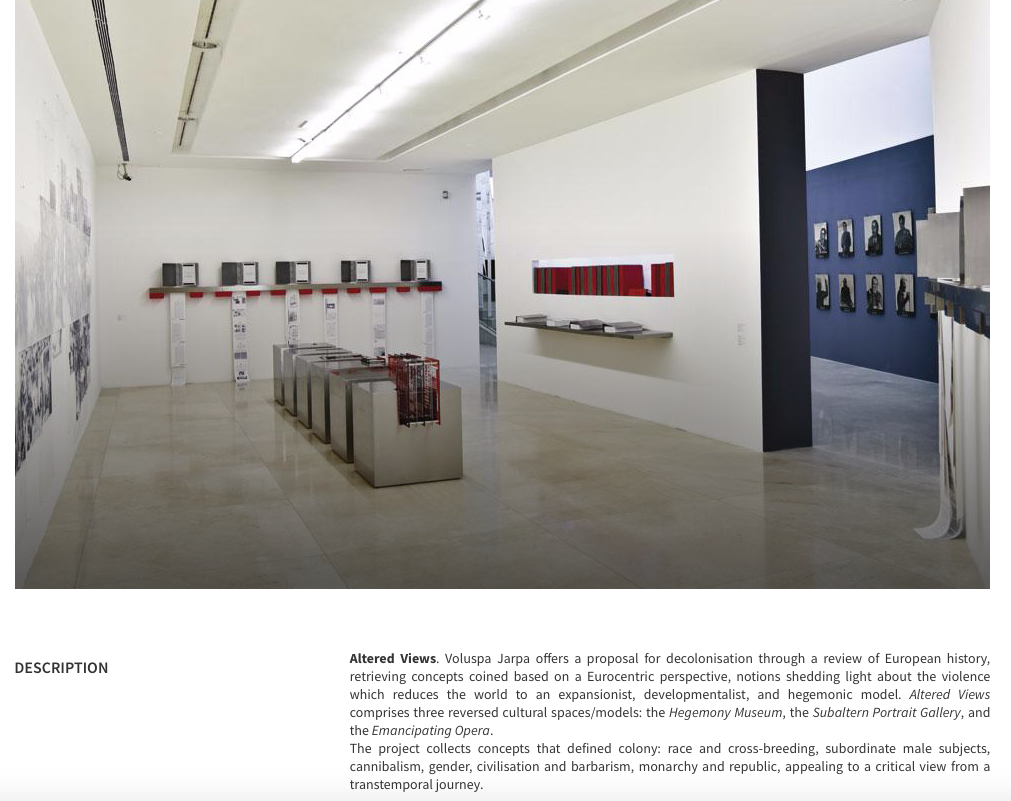

CHILE PAVILION:

Chile Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

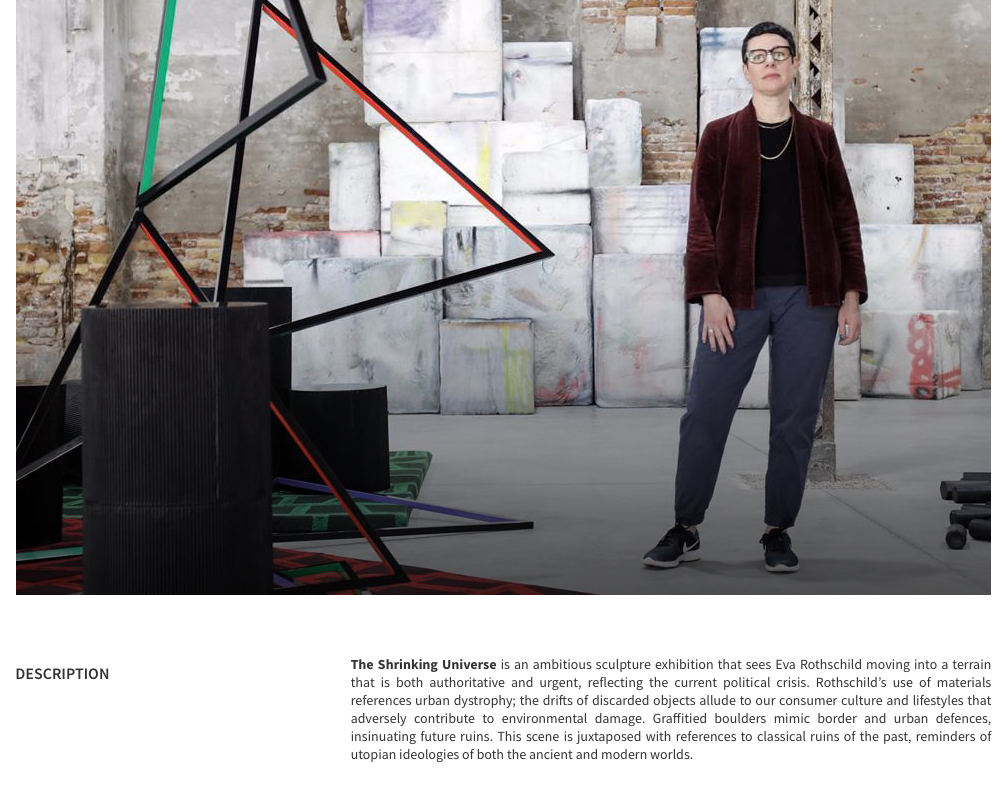

IRELAND PAVILION:

Ireland Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

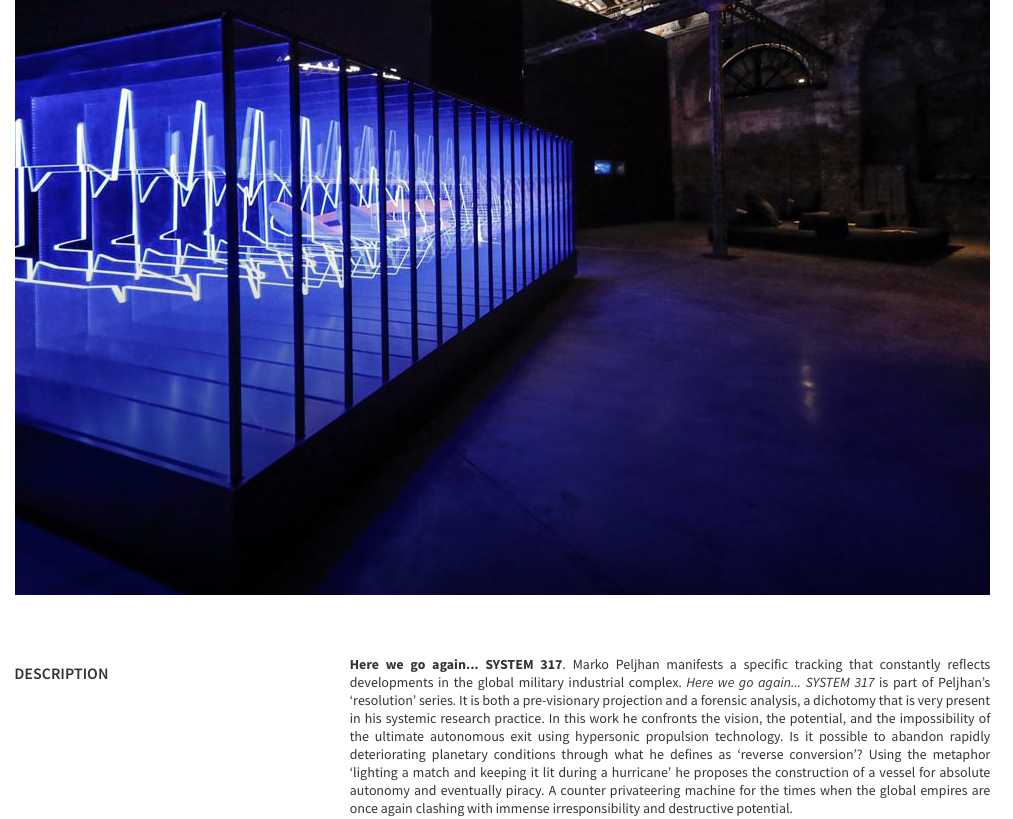

REPUBLIC OF SLOVENIA PAVILION:

Republic of Slovenia Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

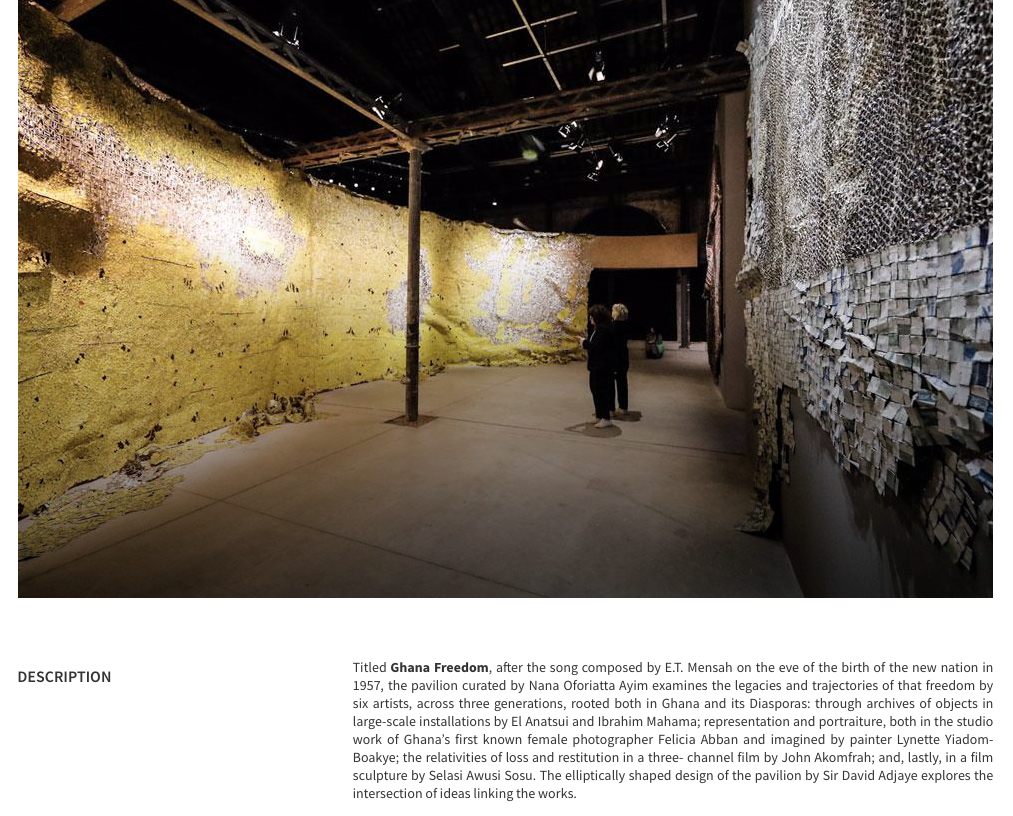

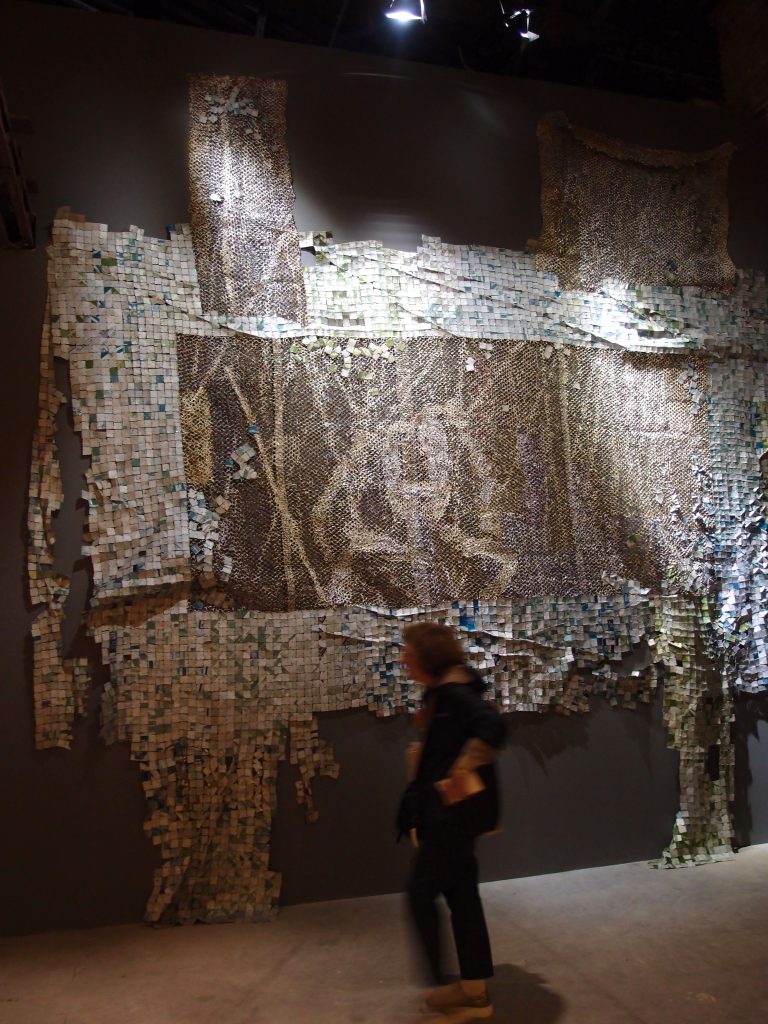

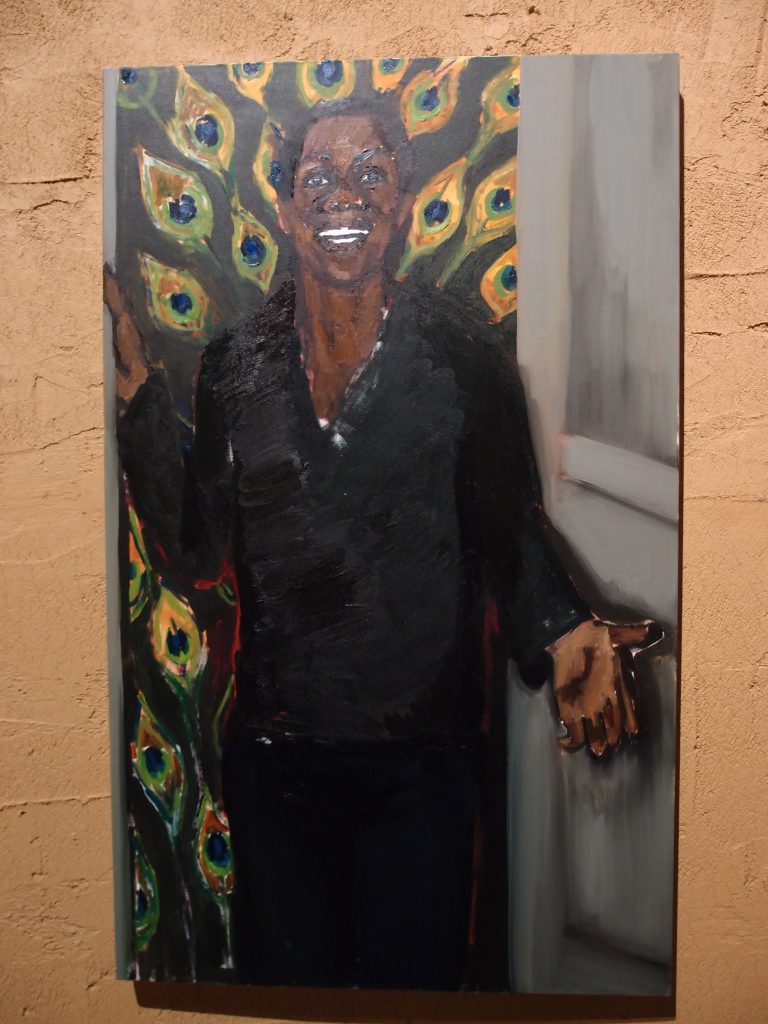

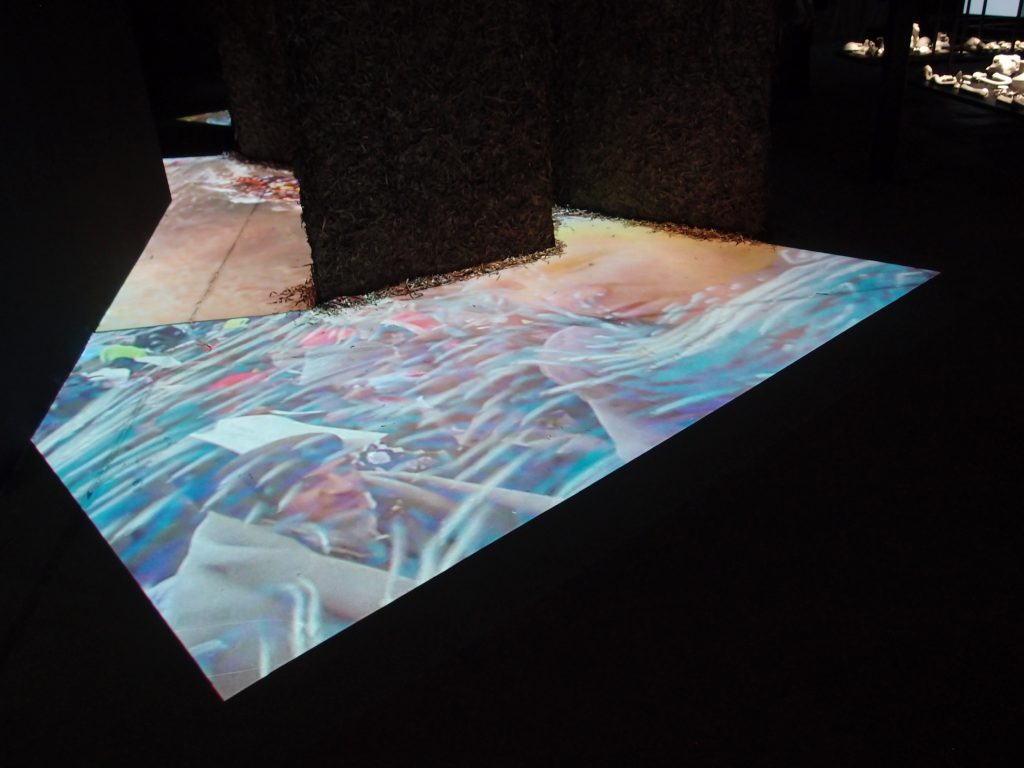

GHANA PAVILION:

Ghana Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

MALTA PAVILION:

Malta Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

After all of those dimly-lit galleries, I need to see more daylight. Since I began working my way backwards through the Arsenale exhibits, I’ve just now begun to run headlong into the art-crowds who

began their tours at the

correct–and opposite–end of the Showgrounds.

![]()

GEORGIA PAVILION:

Georgia Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

LATVIA PAVILION:

Latvia Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

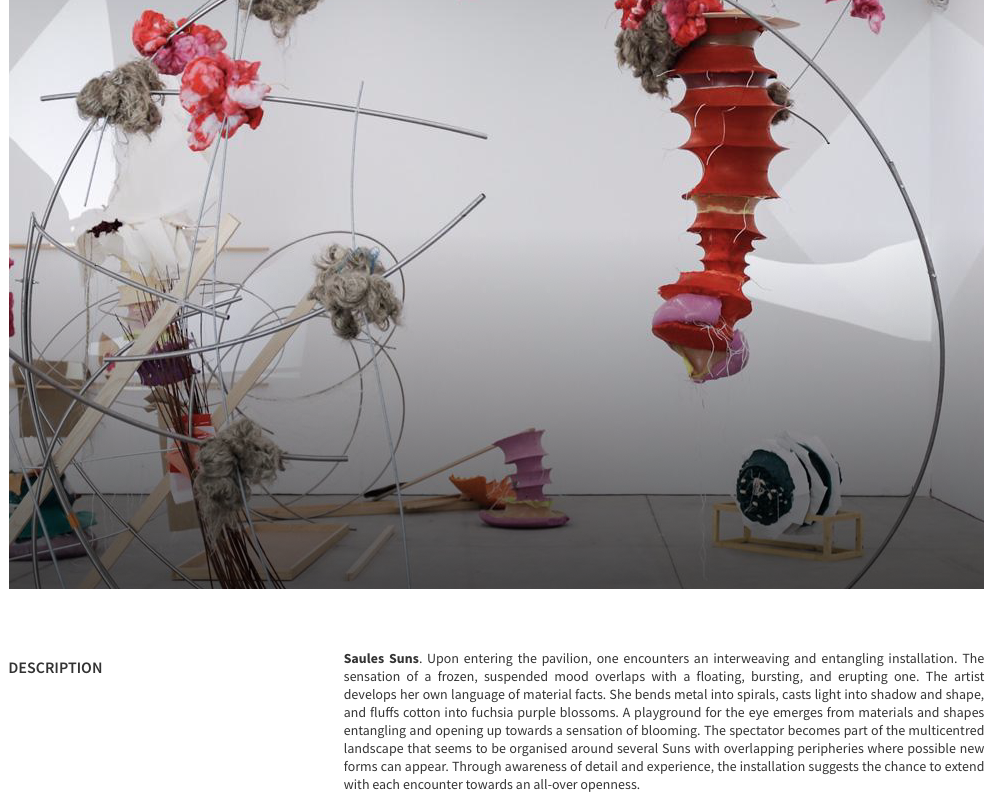

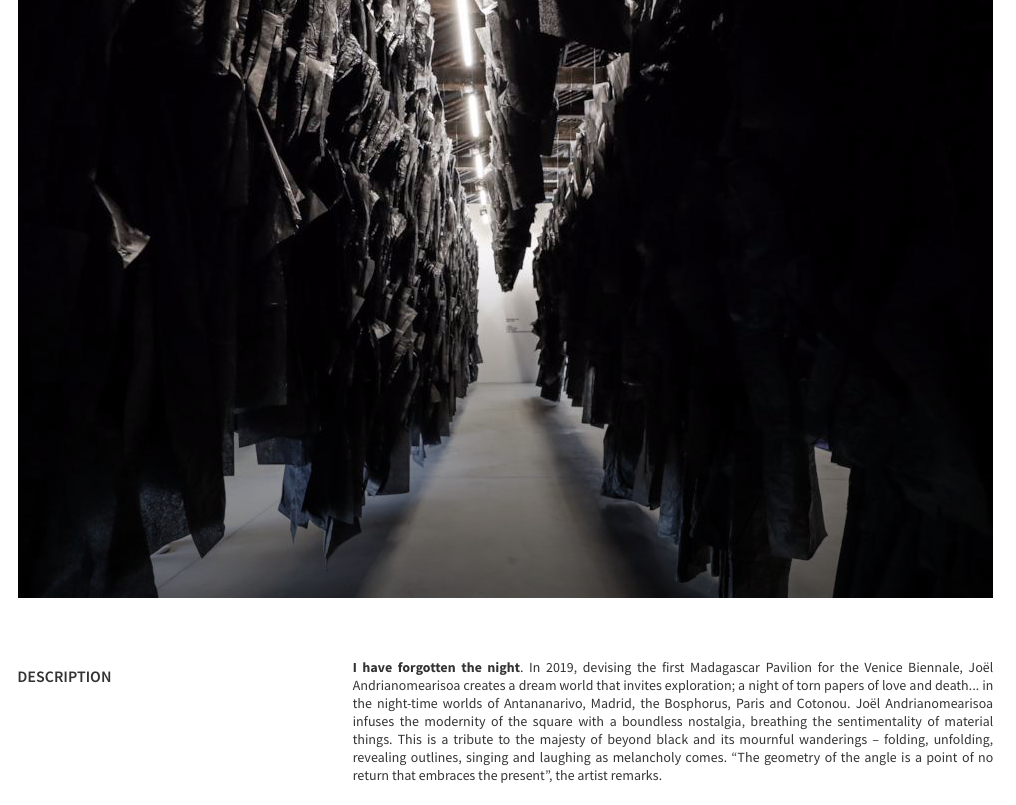

MADAGASCAR PAVILION:

Madagascar Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

ALBANIA PAVILION:

Albania Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

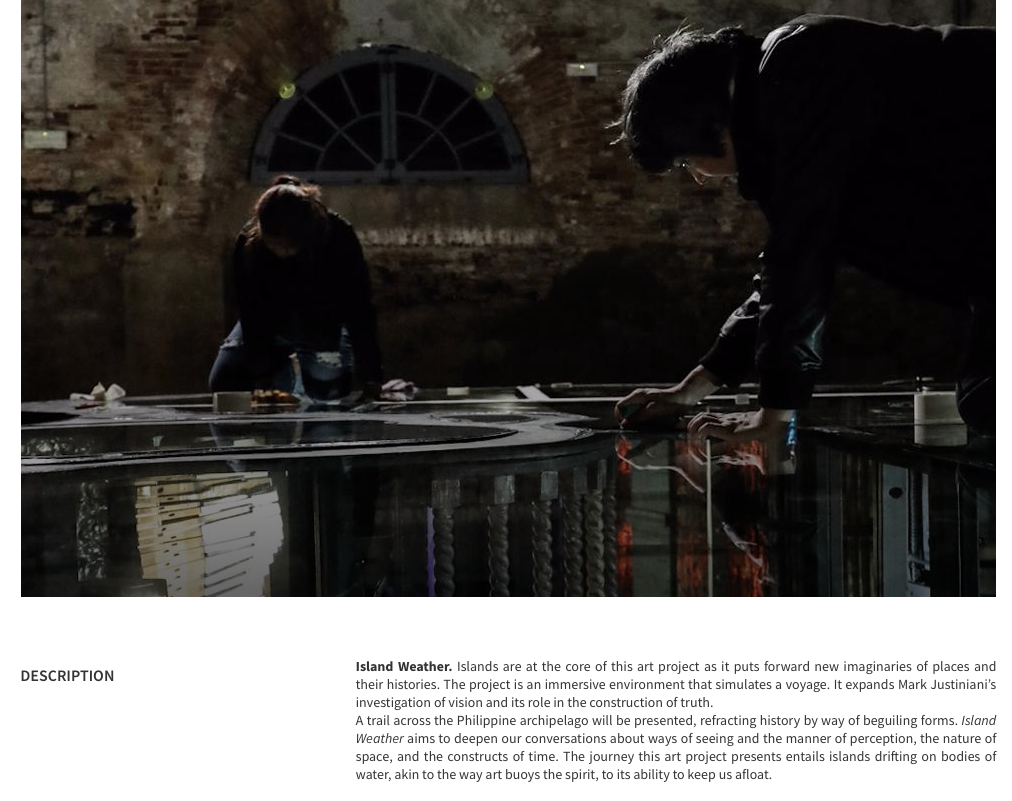

PHILIPPINES PAVILION:

Philippines Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

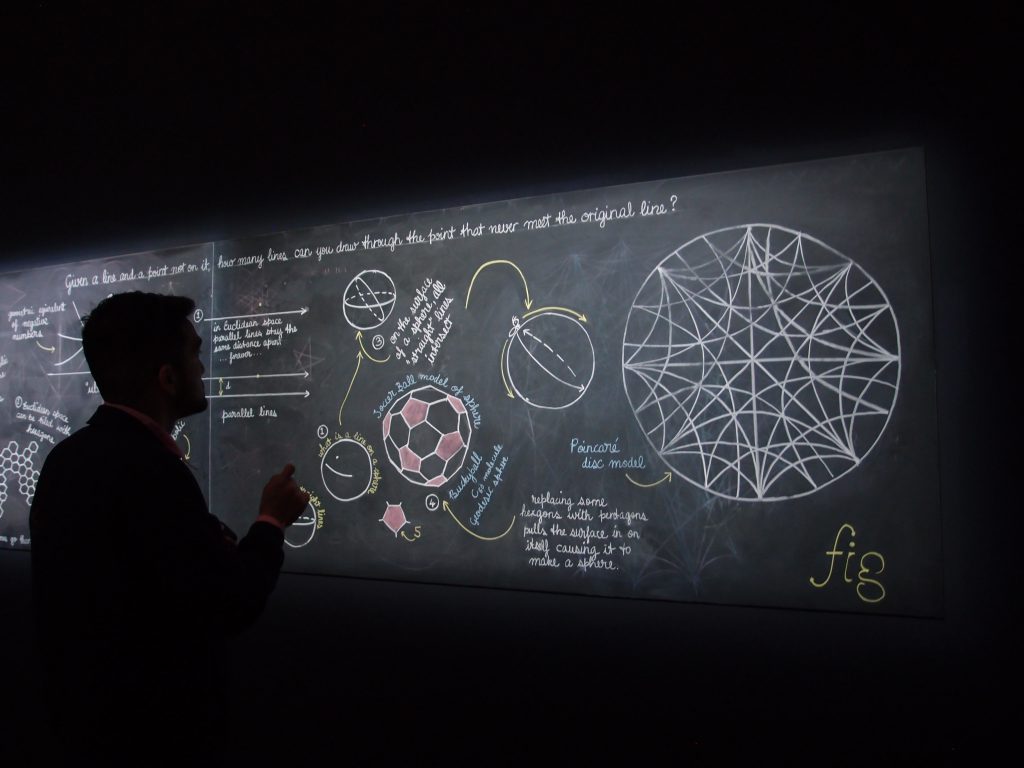

Join me, as I’m working my way from back to front, through the Corderie Exhibition Halls. Here’s a sampling of the work of artists (a complete list of all of these Artists is shown below) who were invited be part of the group show

“May You Live In Interesting Times.”

Artists’ Works in the

Arsenale’s Corderie halls.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

WHEW !!! And remember: what I’ve just shown you is but a tip of the Art-Iceberg:

Biennale-Visiting requires stamina.

Outside again, for another gulp of fresh air:

We’ll now zip up into the Sale d‘Armi, where there are still more National Pavilions:

![]()

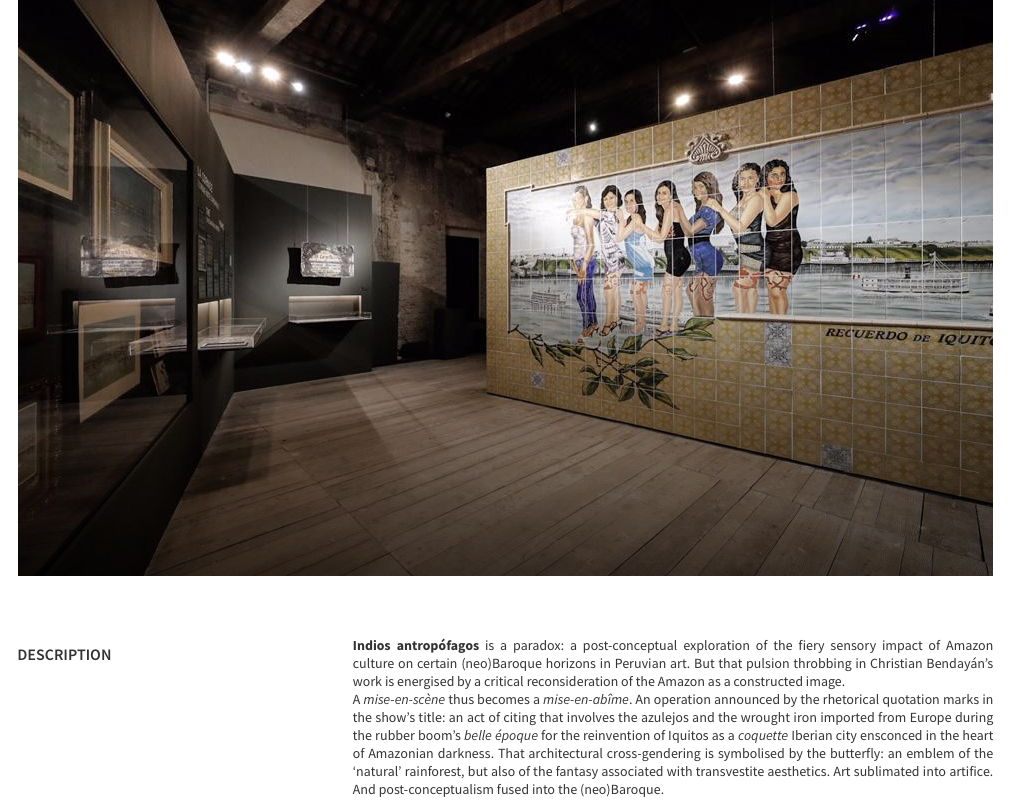

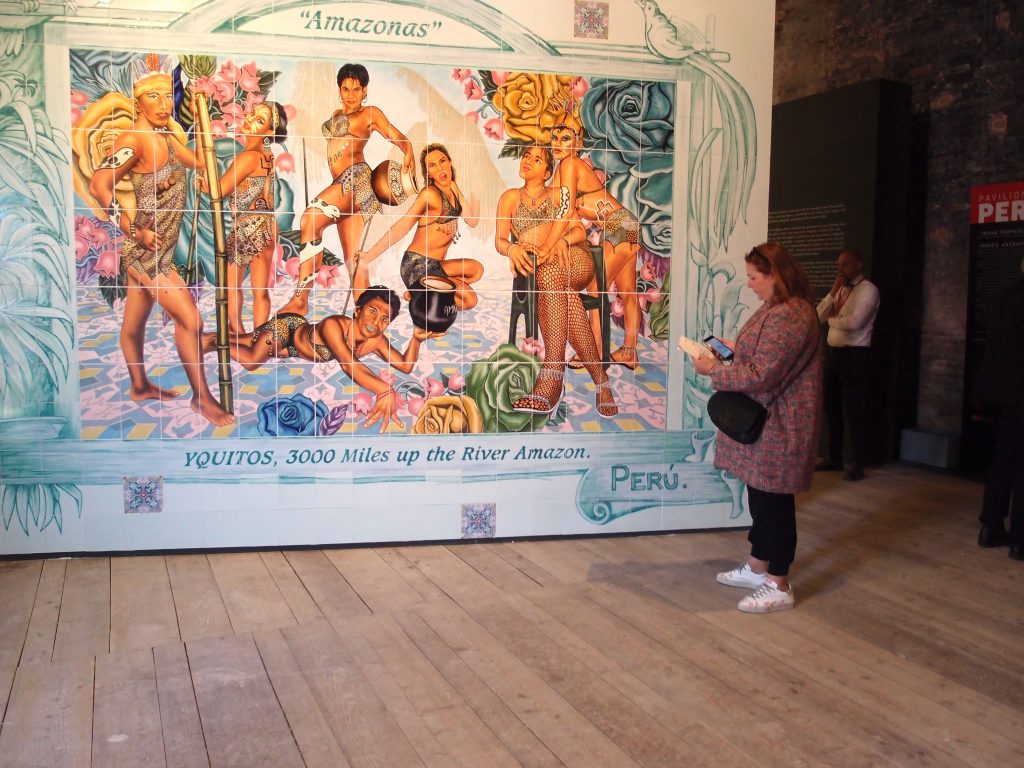

PERU PAVILION:

Peru Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

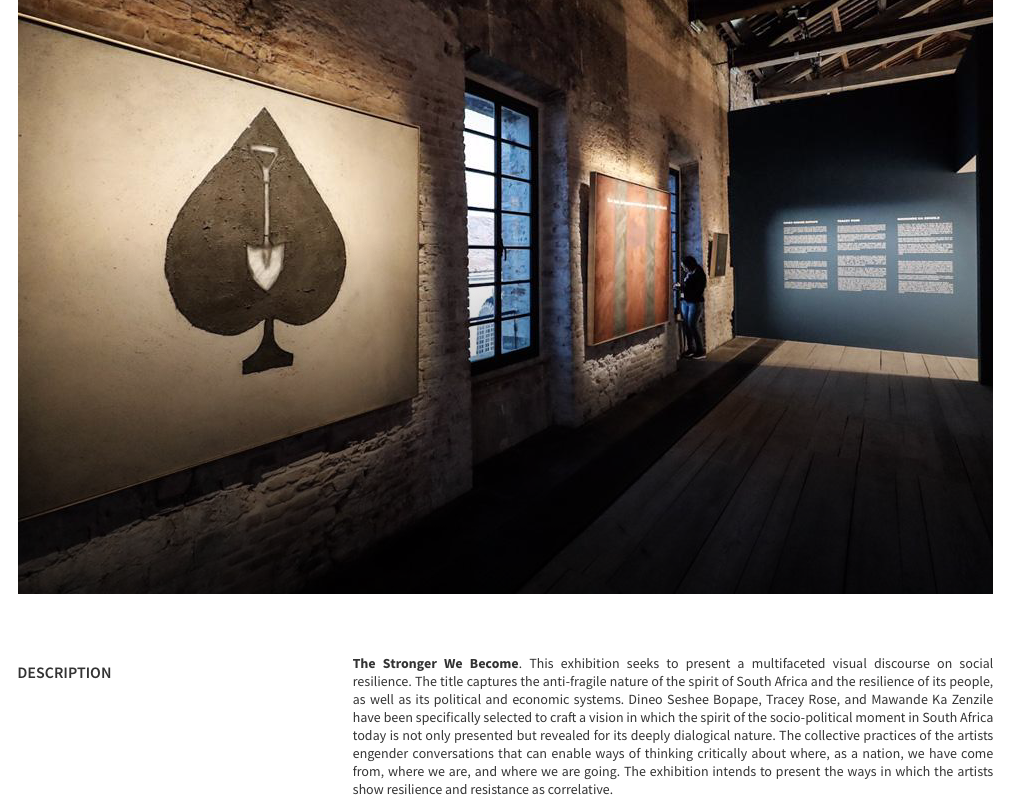

REPUBLIC OF SOUTH AFRICA PAVILION:

Republic of South Africa Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of La Biennale

![]()

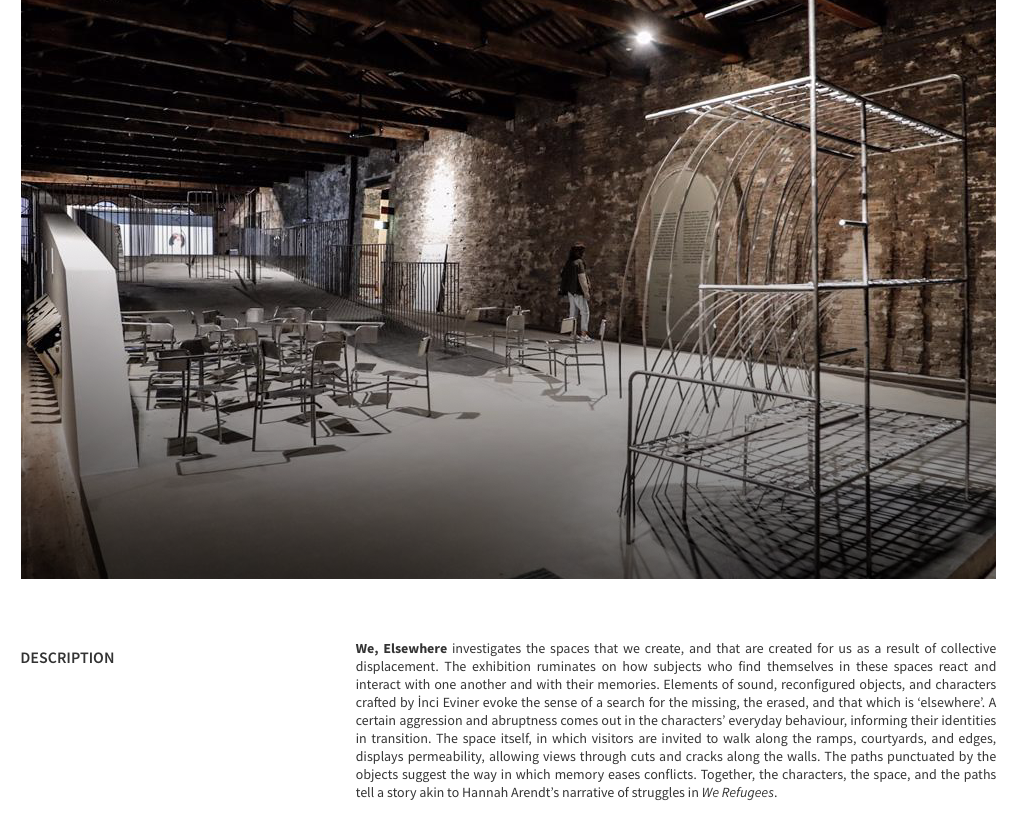

TURKEY PAVILION:

Turkey Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

GRAND DUCHY OF LUXEMBOURG PAVILION:

Grand Duchy of Luxembourg Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

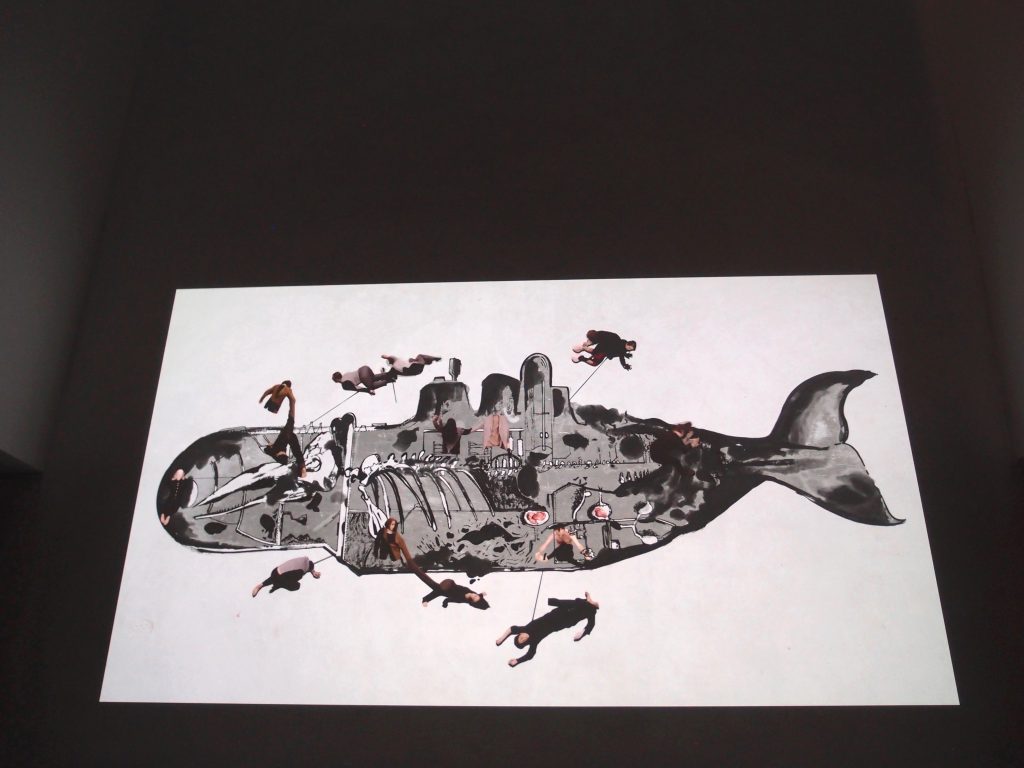

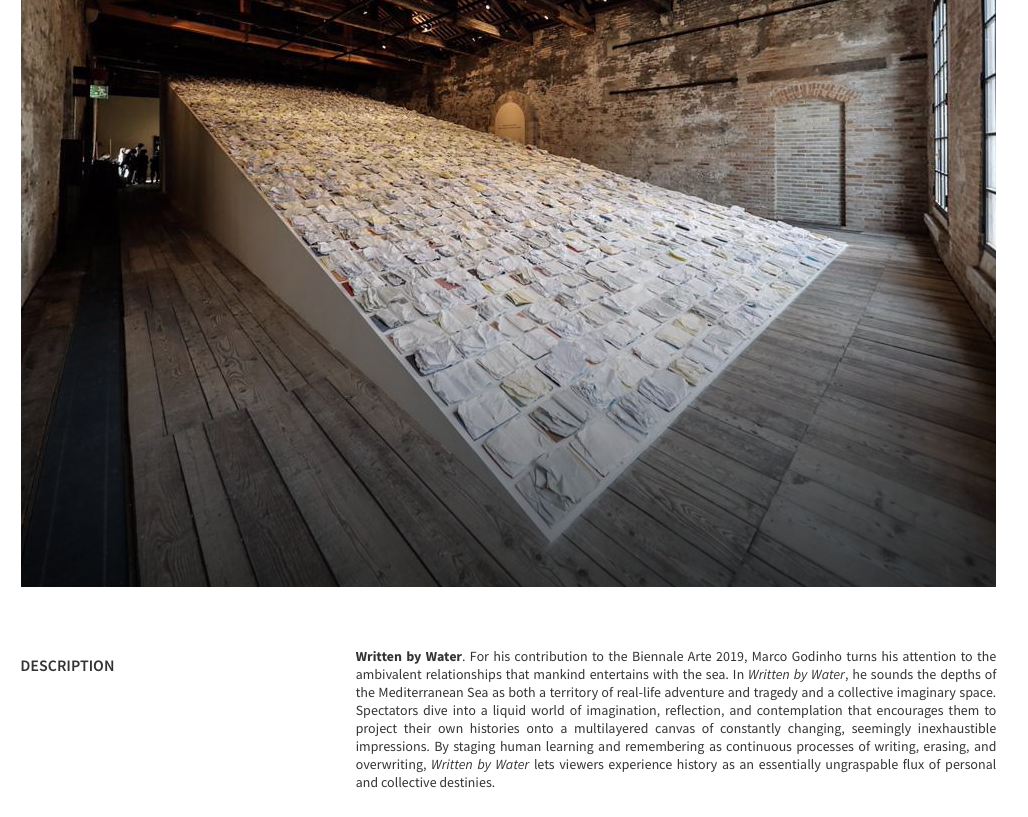

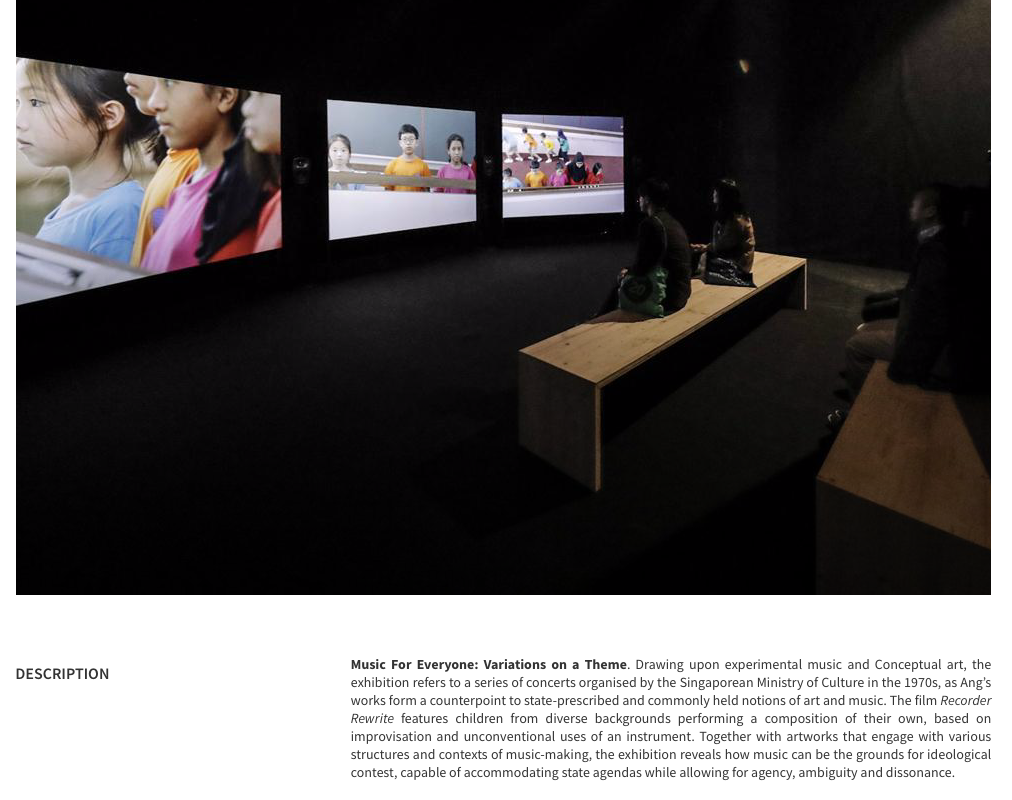

SINGAPORE PAVILION:

Singapore Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

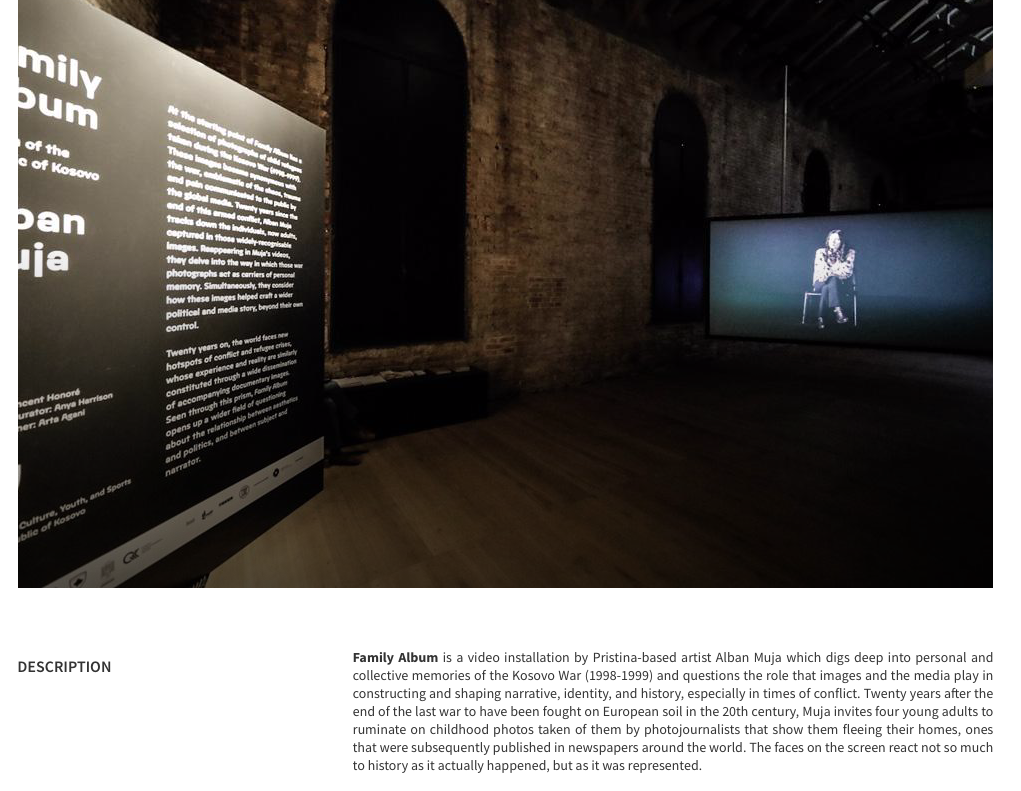

REPUBLIC OF KOSOVO PAVILION:

Republic of Kosovo Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

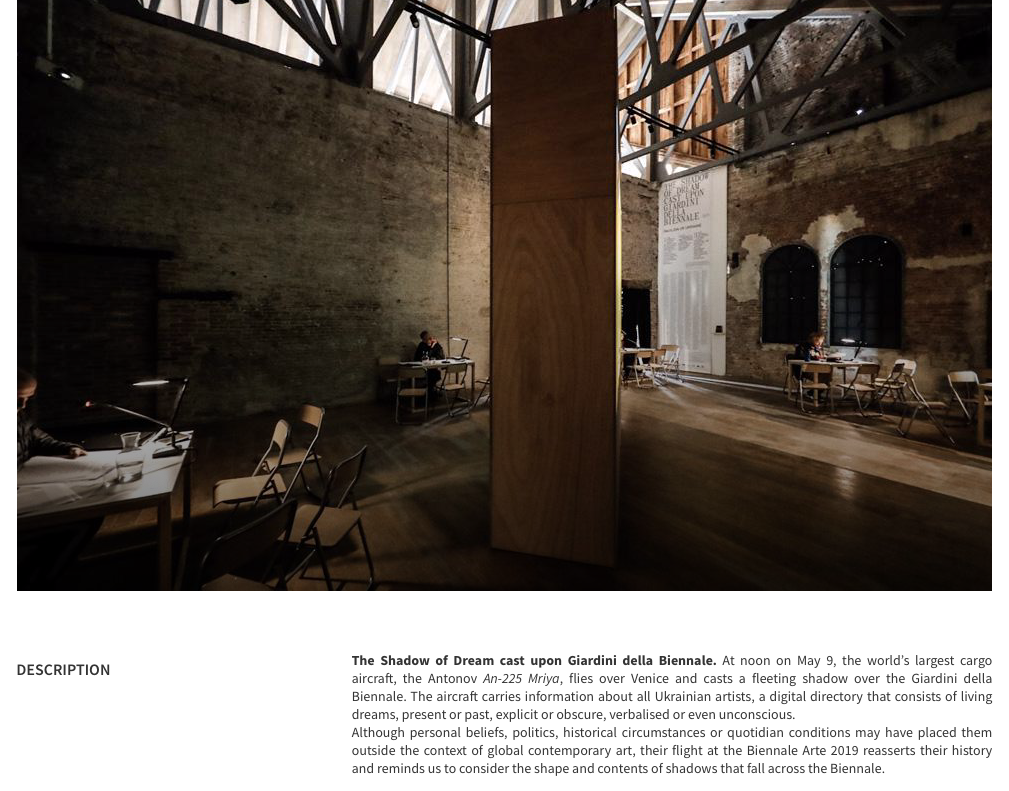

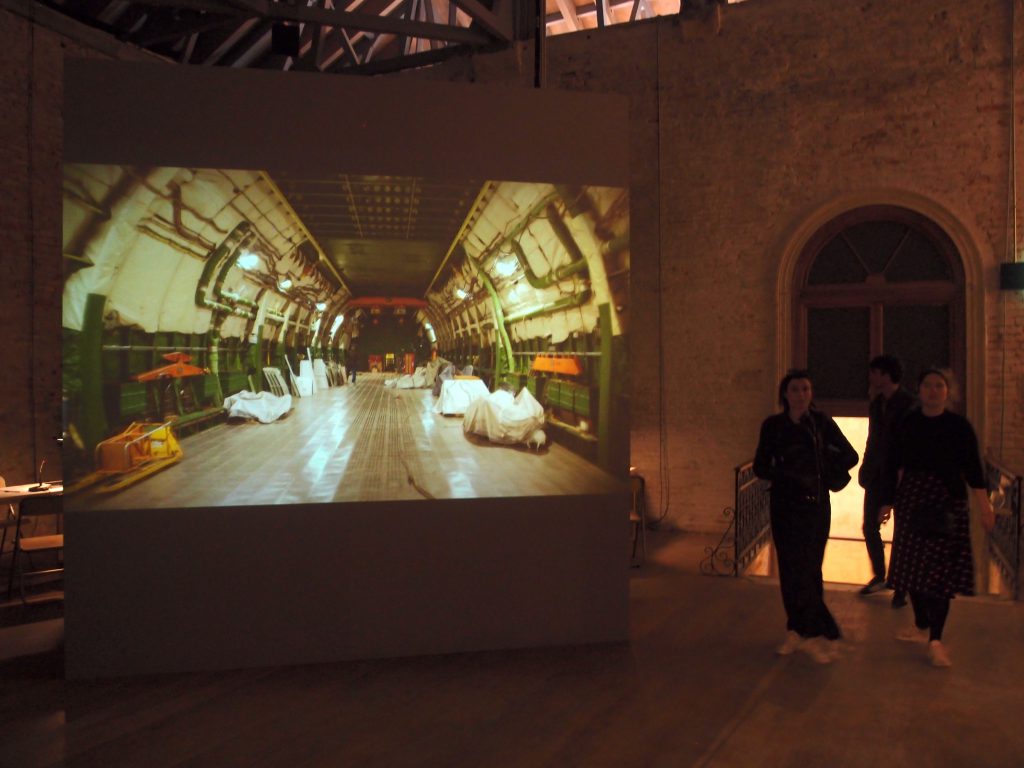

UKRAINE PAVILION:

Ukraine Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

Miraculously, there was a corner of the top floor of Sale d’Armi which hadn’t been used for a pavilion. Here’s a reminder of what spaces in the Arsenale look like, when not

being used for Biennale, followed by some views of the Darsena Grande.

![]()

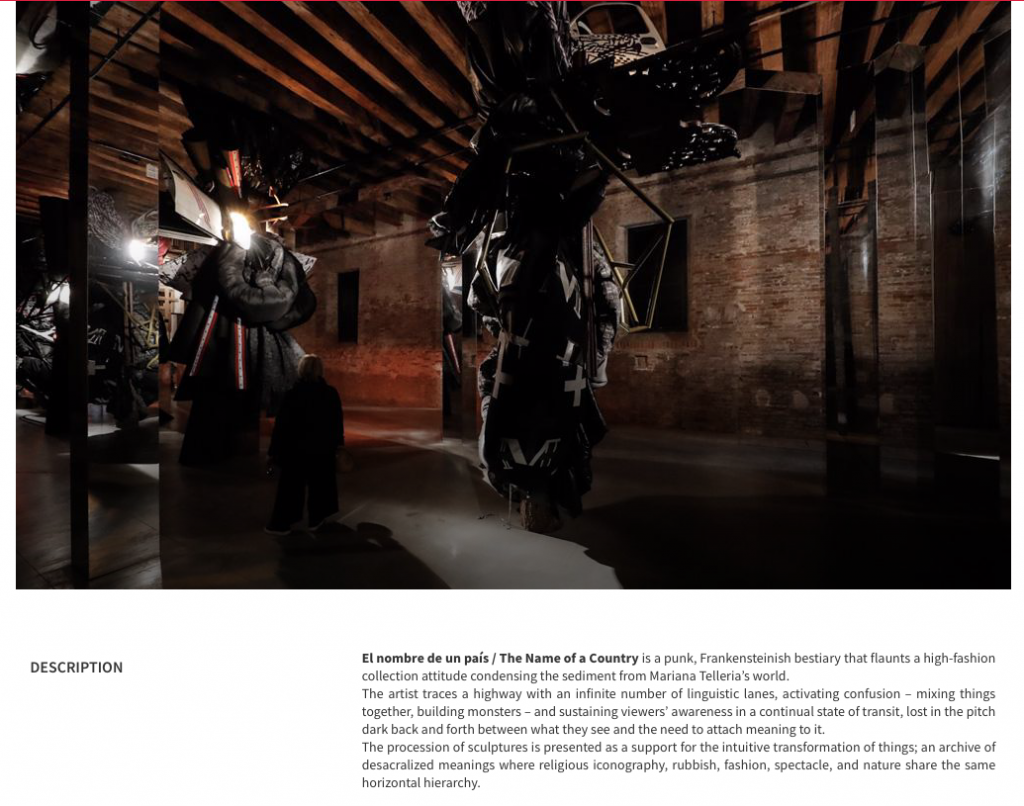

MEXICO PAVILION:

Mexico Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

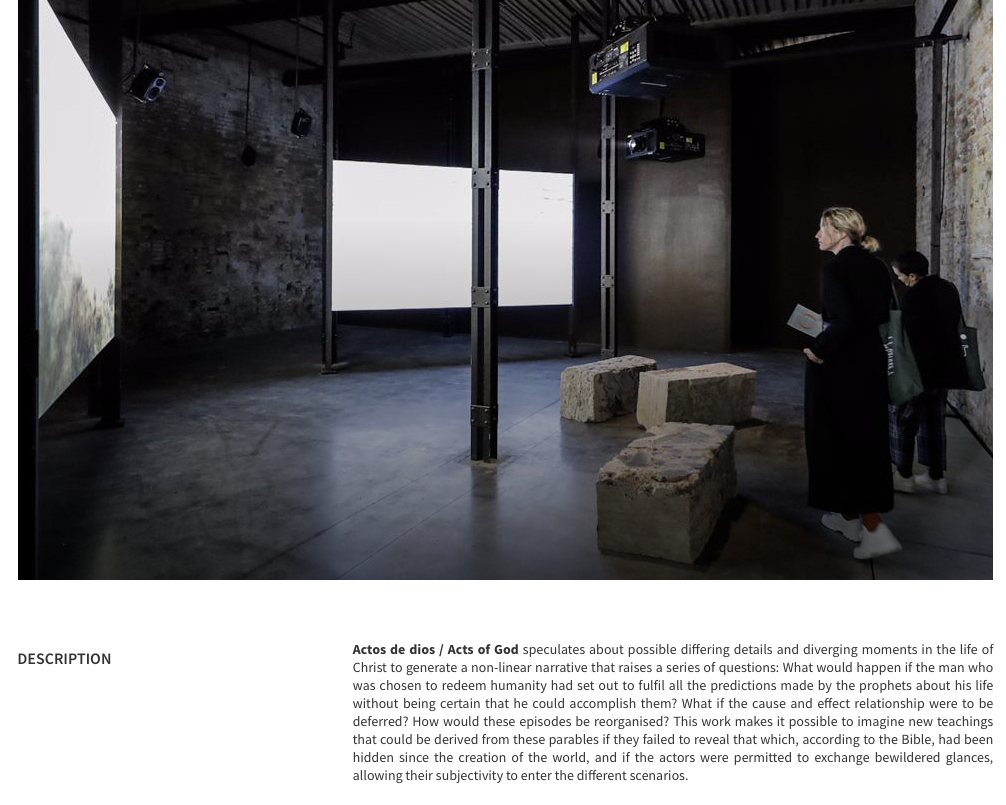

ARGENTINA PAVILION:

Argentina Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

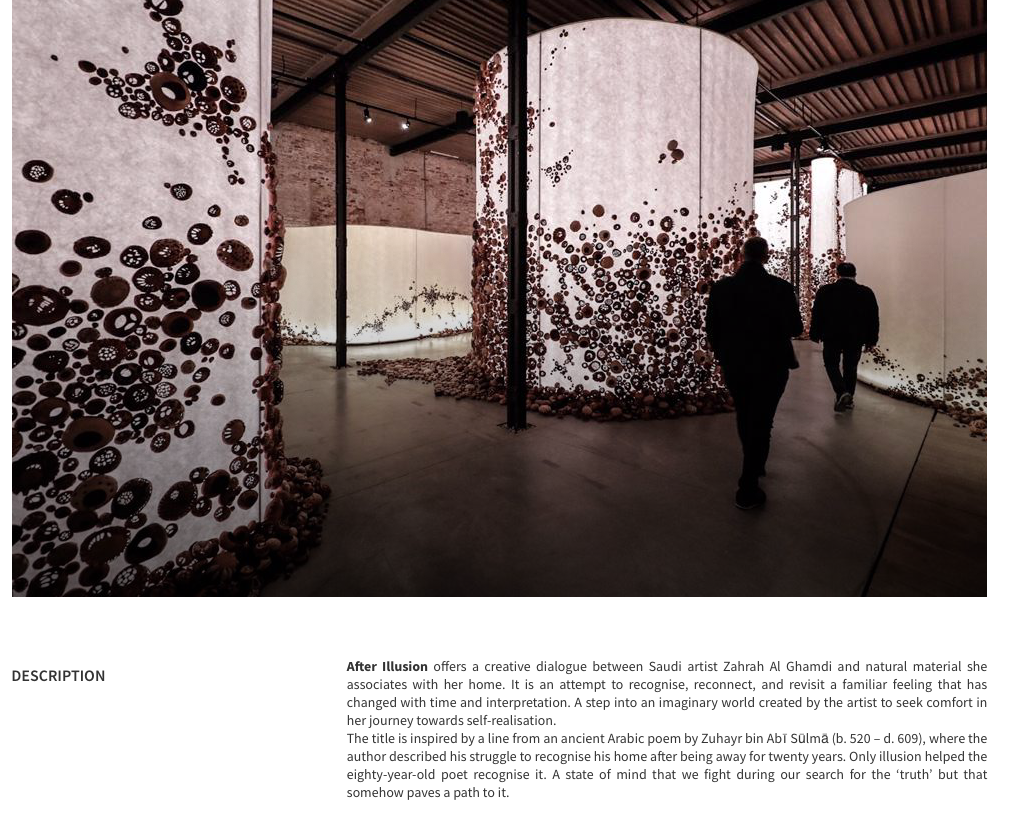

SAUDI ARABIA PAVILION:

Saudi Arabia Pavilion. Summary of Exhibit. Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

Having made my best effort to see all of the Arsenale exhibits, I trudged down the long alley-way, toward the entrance. I paused and looked back from where I’d come: the pedestrians behind me seemed to exude the same fatigue that I felt:

I ambled, towards Via Garibaldi:

To cap off my Arsenale-immersion, I wanted to revisit the Arsenale’s

Water Gate, which is on the south-western corner of the former industrial complex, in the Castello neighborhood.

Aerial View of Arsenale’s

Water Gate

I’m approaching the

Arsenale’s grand

Water Gate

Especially as Venice being is threatened by rising seas,

it is reassuring to inhabit a space in year 2019 which looks very much like it did when

Canaletto painted this scene, in 1732:

Canaletto’s 1732 painting of the Water Gate

More views of the Arsenale’s Water Gate area:

And I’m always amused by the yachts which anchor near Via Garibaldi, during Biennale:

![]()

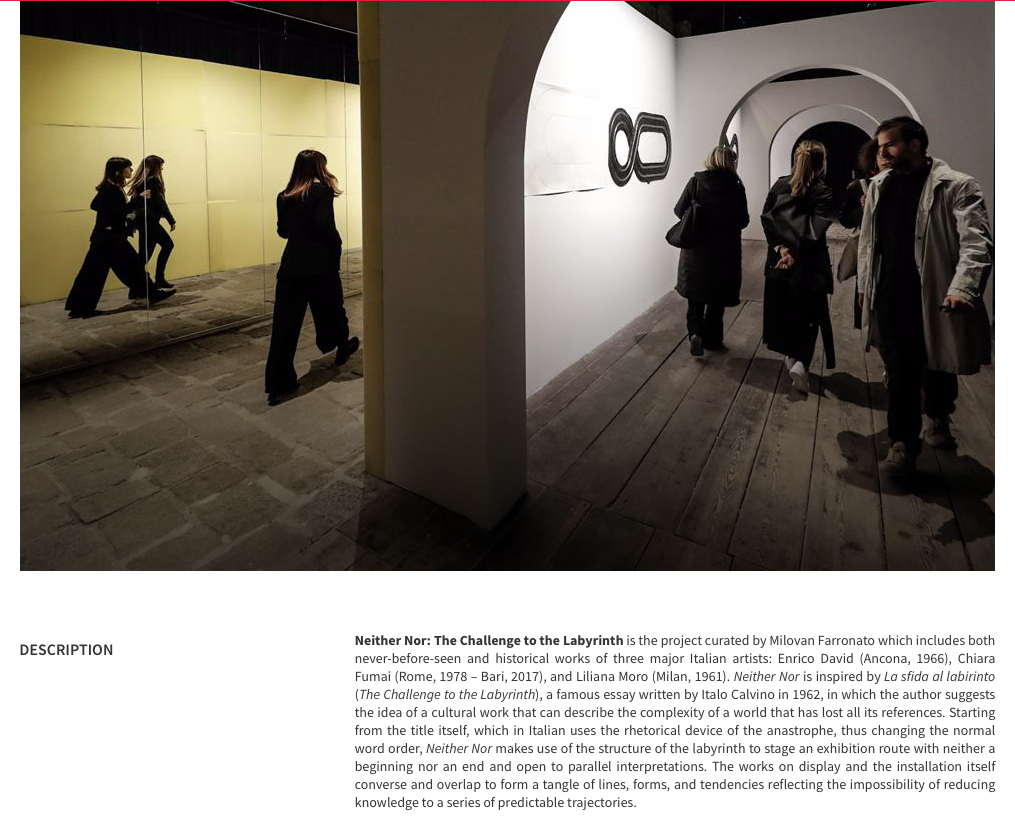

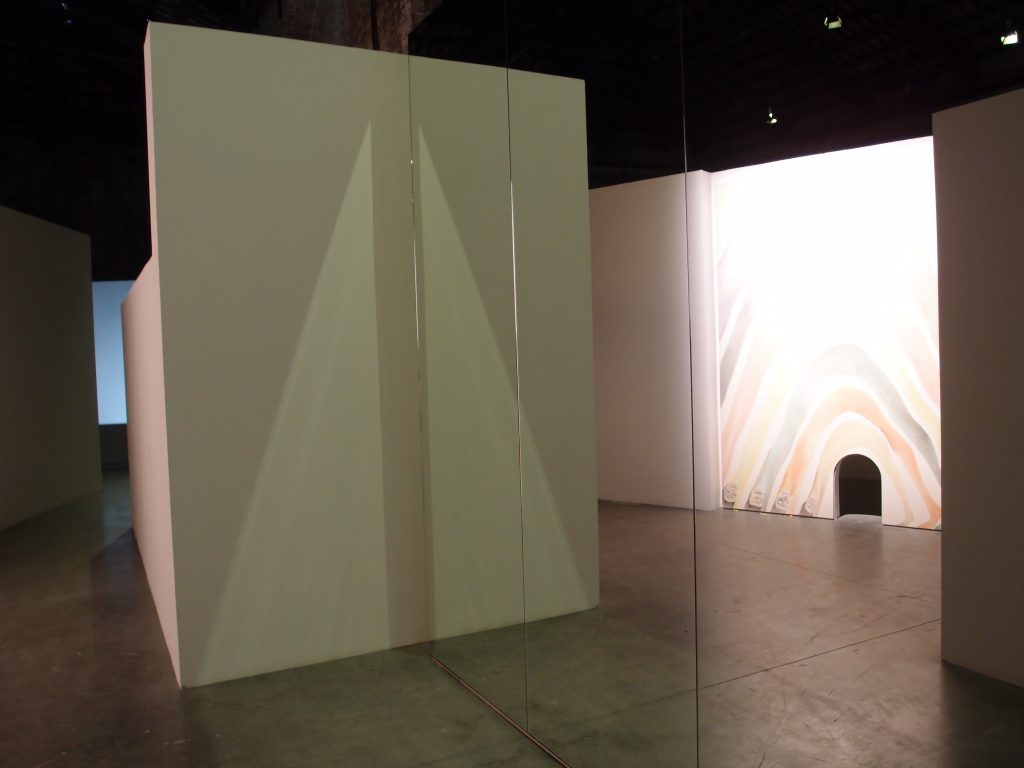

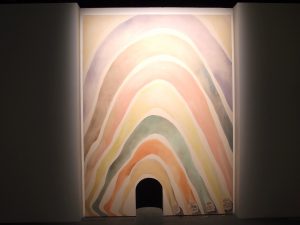

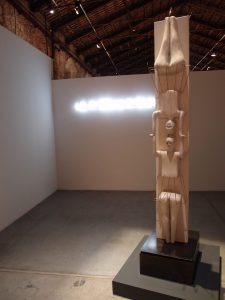

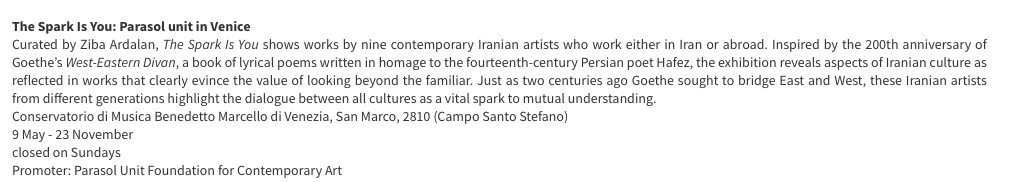

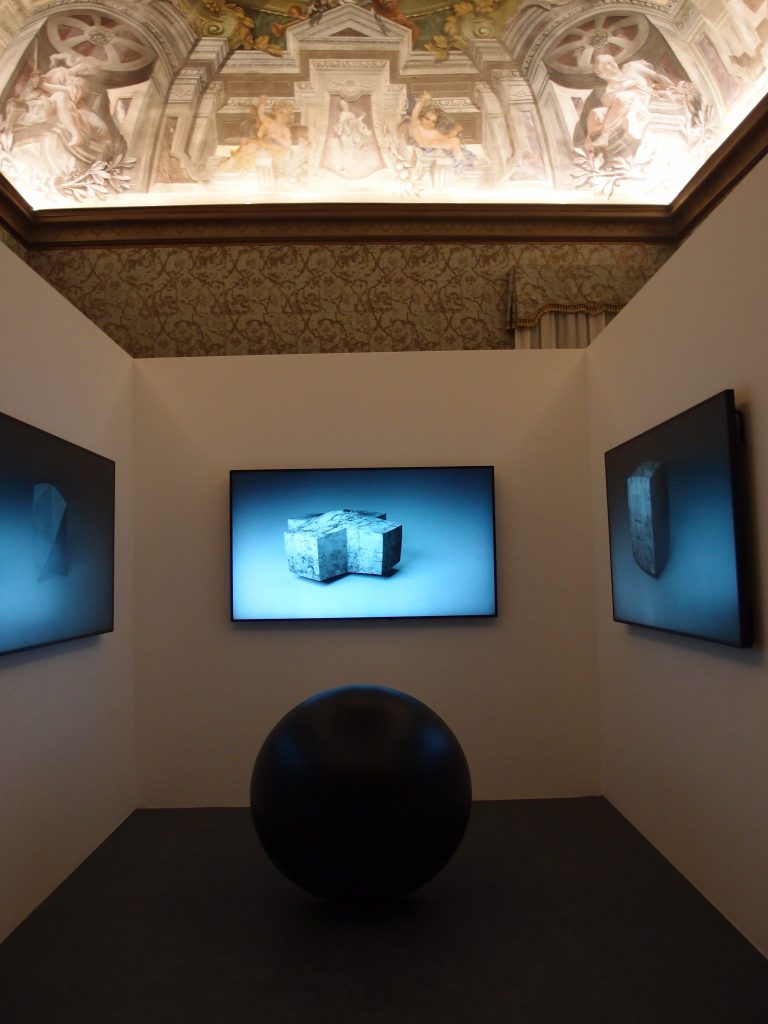

On and off, following my two long, Press Day visits to La Biennale, I wandered through greater Venice, in search of the smaller National Exhibits and Collateral Events that are scattered all across the City’s neighborhoods: in Cannaregio, Castello, Dorsoduro, Santa Croce and San Marco. I’ll leave you with images of a striking Biennale Collateral Event—

THE SPARK IS YOU: PARASOL UNIT IN VENICE—which is

at the Conservatorio di Musica Benedetto, Marcello di Venezia, San Marco. In this Exhibit

we see yet another example of how Venice’s antique palazzos can become superb stages for

contemporary art.

The Spark Is You.

Summary of

Collateral Event.

Image courtesy of LaBiennale

![]()

What then, to make of the Spectacle that is La Biennale? Fashions and tastes in art are subjective, and so, in these two extended BIENNALE DIARIES, I’ve largely allowed my photos to speak for themselves. I’ve always been especially moved by paintings: both representational and abstract. When accomplished Artists deploy brushes, pigments, superb technique and striking concepts, they become Alchemists whose transmutations are so effective that the results seem miraculous. At this year’s Biennale, I longed to see more demonstrations of this painterly magic. However, the practice of making sculpture—be it traditional, kinetic, or conceptual–seems to be flourishing. But the profusion of films at Biennale, presented in grim gallery spaces, did nothing to inspire me. Certainly, in these “Interesting Times,” there is much cause for doubt, disquiet and anguish in the World…and much of the art on display at La Biennale mirrored these feelings. Following my hours and hours of Biennale-Looking, the Exhibits I remembered—and was most uplifted by and grateful for—were those that made the most generous, and well-integrated, presentations. I knew such presentations were successful

when I went away from them with new understanding about aspects of a nation’s culture,

its challenges, its history, and its aesthetic values. The national pavilions of Ghana,

Italy, Serbia and Japan all excelled in this difficult feat of Showmanship.

![]()

Copyright 2019. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

2 Responses to Venice: BIENNALE ARTE 2019. Part Two