Broughton Grange Gardens & Arboretum: set on 400 acres of land, overlooking a beautiful Oxfordshire valley. This Parterre was begun in 2001, when landscape designer Tom Stuart-Smith was commissioned by the residents to transform a six acre, south-facing field into a walled garden. For the lower terrace of the Walled Garden, Stuart-Smith concocted a

Parterre that gives a 21st century twist to traditional parterre form. His design takes inspiration from the leaf cell structure of native trees. The graphic structure of the Parterre is formed by sections of tightly-clipped hedging, consisting of beech, oak, and ash. In late October, summer bedding plants are removed and approximately 5000 tulip bulbs, of 13 varieties, are planted. In late April and early May, following the tulip display, summer-through-autumn ornamentals such as Brassica, Heliotroplum and Rudbeckia are planted to fill the Parterre’s gaps.

![]()

In a normal summer, during non-pandemic-times, I’d be rattling around in England and in Italy, continuing my explorations of landscapes, architecture, art, cultural history and gardens. But now, in year 2020, the more I’m forced to settle into covid-avoidance-immobility, the more

vivid my house-and-garden-bound days here in rural New Hampshire are becoming; this because I’m compelled to pay closer attention to my surroundings. Really SEEING and savoring, and then flexibly responding to every granule of existence is exactly the approach I’ve always used while traveling and adapting to foreign lands. It’s taken this planet-wide nightmare to instruct me to finally apply that same lucidity to my NON-traveling days, and I’ve begun to develop the patience that’ll be required for me to remain strong, and kind, as horrors beset the World.

My list of the Best Gardens of the Cotswolds and Nearby Regions has been a long time in the making. This DIARY is reference material, to be bookmarked, and then browsed, as pangs of travel-longing afflict you.

But is our contemplation of the beauties of English gardens relevant and seemly, while hundreds of millions of people are suffering and in mortal danger? Of course it is. Whenever we’re outdoors, our animal-spirits mend, and our hopes revive. During this era of the plague, if we cannot be physically present in the wonderful places that I’ll soon show you, we can at least appreciate their splendors while we look forward to a time when we’ll be free to travel, and all of these gardens will once again be open.

I’ve been producing DIARIES FOR ARMCHAIR TRAVELERS now for 12 years: first presented by New York Social Diary, and since 2012 published under my own steam. From the moment I began to compile my travel photos and compose accompanying narratives, I felt my furrowed brow relaxing, and the fraught strands of my life unsnarling. Although the purpose of my travelogues has always been primarily to share news of places that exemplify the best creative energies of human beings, with each act of DIARY-making, my widely-cast net of interests have also organized themselves into a graceful and rational Whole, where there are no more than six degrees of separation between my multitudes of lifelong obsessions.

When I was eight, I began an album of postcards — mostly received from my father — called “Beautiful Places & Nature.” E.B.Quick spent most weeks away, traveling to far-off places for his work, and I craved glimpses of the wonders that I knew he MUST have been seeing!

Although I had no vocabulary then to describe my discontent, I found suburban existence during the late 1950s and early 60s to be sterile and suffocating; my outings were only to school, an occasional movie (BLISS), and to shopping malls. We moved constantly, from my California birthplace, to Pennsylvania, and New Jersey, and Massachusetts. Only my visits with relatives in the Bay Area, or in Princeton, New Jersey sustained me: in those two locales I saw things which confirmed my notion that people doing interesting work

in beautiful places did indeed exist.

In San Francisco, my mother’s sister Audrey Sochor and her husband Arthur took me to the Japanese Tea Garden, Conservatory of Flowers, the DeYoung, the Academy of Sciences, and Botanical Garden in Golden Gate Park, and we never missed stopping at Bernard Maybeck’s Palace of Fine Arts near the Marina. On the East Coast, during my frequent stays in Princeton with my grandparents Nellie and Clifford Quick, our days were filled with journeys to museums, historical sites and parks, to working farms and to grand gardens (sadly, New Jersey, once known as the “Garden State” is no longer an agricultural paradise). And my architect grandfather, who worked for the University, would always

take me to see the buildings where he’d overseen the construction…most notably the Chapel.

Perhaps more importantly, he allowed me at a tender age complete access to his trove

of architecture books. Although he was a Beaux-Arts-trained architect, his library was full of monographs on modern masters like Le Corbusier, Gropius, van der Rohe, Breuer, and Aalto. At age 10, after I’d returned from another idyllic visit with my worldly relatives, I grimly announced to my mother: “I see nothing has changed.” My parents must have found it unrewarding to have me around. Biding my time until adulthood—when I could begin to refashion my life—was always the goal. Inevitably, several decades passed until the actualities of my existence began to catch up with my dreams.

Age 25, when I was studying to become an architect. Life, being its Practical Self, instead had me become a book-publishing consultant.

But 42 years later, in June 2020, I was wrapping up nearly 3 years of designing & building additions to my New Hampshire home and garden.

During all of the summers when I’ve been lucky enough to wander across England and Italy, I’ve never taken for granted the sheer miracle of the ways in which all the pieces of my travel puzzles have smoothly fitted together. Now, in this period of stillness, I am extra appreciative of that freedom of movement.

Finally: With apologies for my extended Preamble, I’ll begin our Tour of some of England’s

most wonderful Gardens! [Note: The contact information provided for each Garden is from pre-covid-times.]

![]()

For a decade now, I’ve spent a month or more during the warmer seasons of each year wandering through England’s gardens. Although my own in-depth explorations of English gardens began in Kent (which is often called “The Garden of England”) most Americans who aspire to visit gardens in the United Kingdom start by dreaming about Cotswolds locations. For several years, Readers have been asking me which Cotswolds gardens should be included on their itineraries; these requests have prompted me to reassess and rank the gardens that are rooted in the hills and plains of England’s central and western counties.

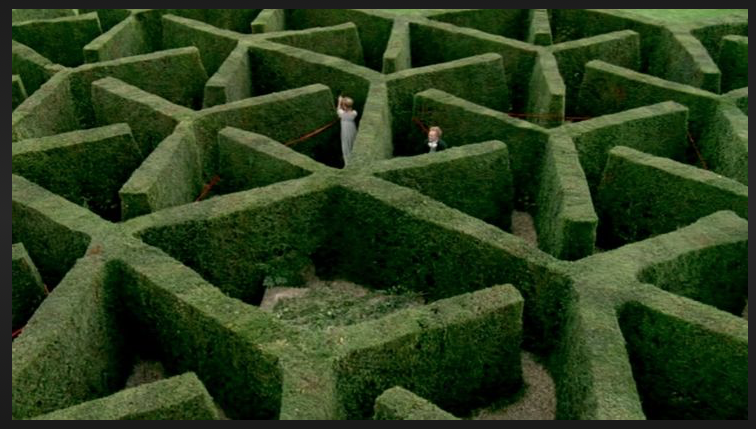

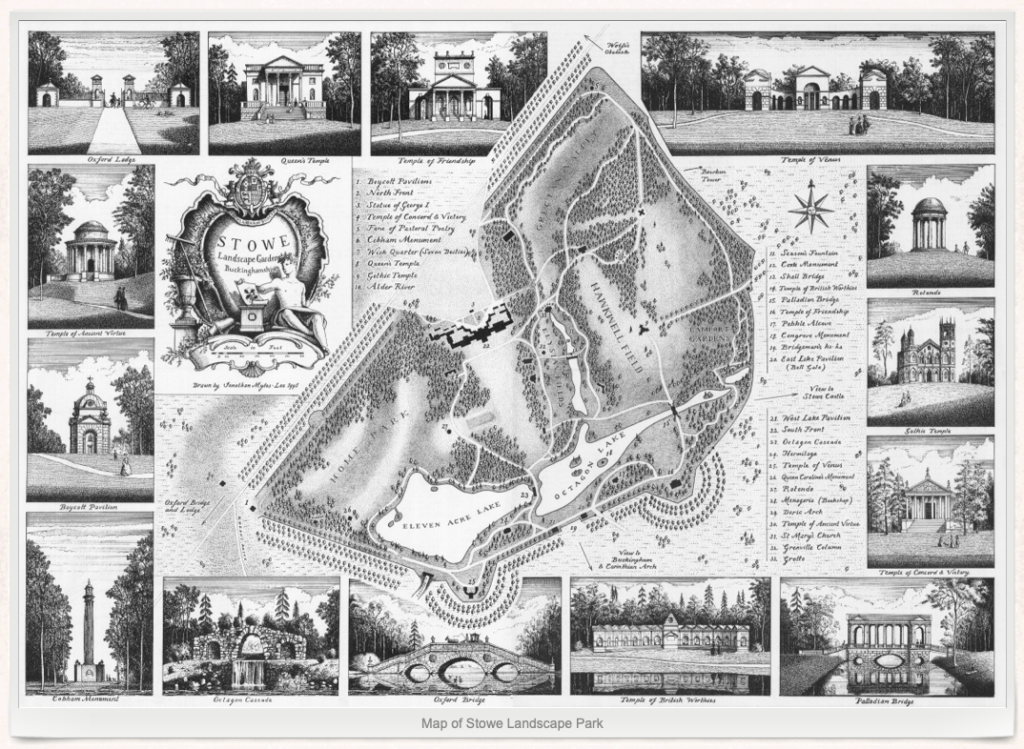

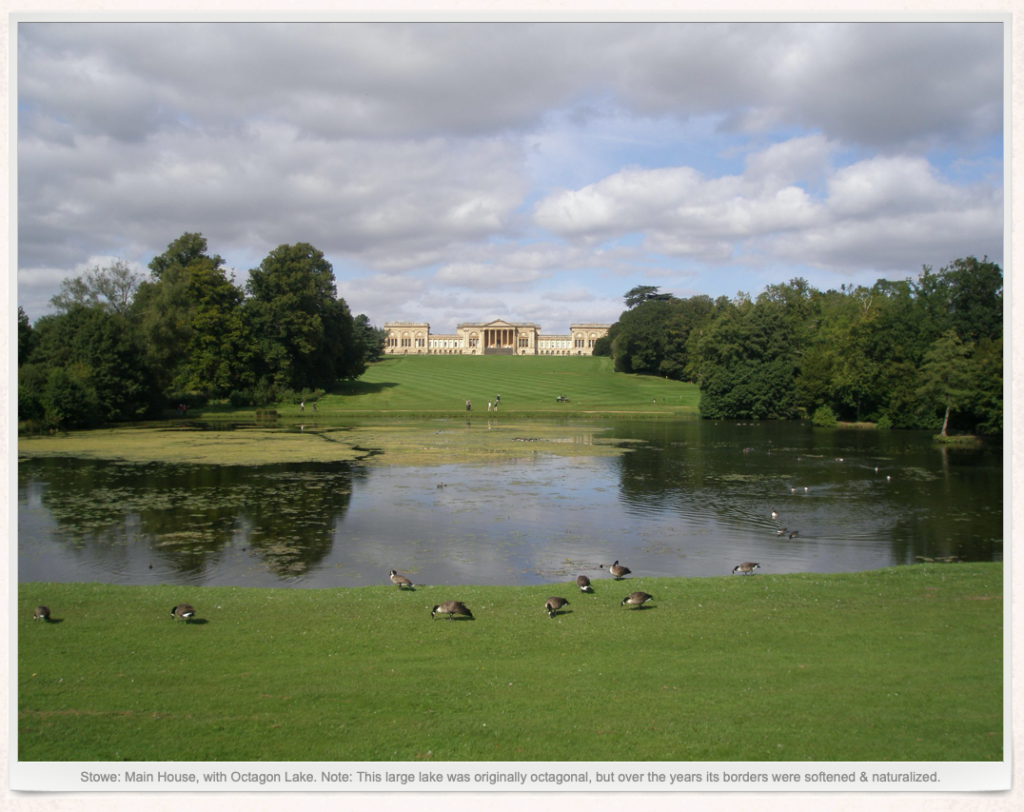

Most garden-hunters, propelled by their own sensibilities, go looking for a particular style of garden. However, after having studied hundreds of gardens, my own tastes have broadened: these days, what I most want is to be surprised–and then instructed–by gardens that have been fashioned in ways that fire my imagination. In the Cotswolds and nearby regions an encyclopedic array of gardens created over the past 300+ years can be found (the most venerable destination on our Tour will be the Dutch-style water gardens of Westbury Court, laid out between 1696 and 1705). Whether you’re hankering after vast parklands, topiaries, follies, charming cottages, manor houses, parterres, labyrinths, plant collections, arboreta, antique gardens, contemporary creations, watery extravaganzas, or displays of statuary, within England’s four adjacent counties of Gloucestershire, Oxfordshire, Buckinghamshire and northern Wiltshire, you’ll discover improbably huge concentrations of Garden Treasure.

![]()

I’ve chosen each of the following 19 gardens because all of the creators of these places have designed singular environments. These gardens, with their powerful and different personalities, are all so CLEAR about what they want to be—so stylistically certain of their Individual Selves—and are all so confidently settled upon their particular locations, that none could be mistaken for being any OTHER garden.

The excellence of these intentional landscapes, which range from compact to sprawling, exists because the garden-designers (& each must certainly have been guided by a personal muse…) have woven together myriad elements (of plants, trees, soil, water, structures, sculpture, and hardscapes) to form inspiring and unforgettable spaces which become worlds unto themselves. Whatever your garden-preferences may be, my illustrations of at least some of these gardens will be sufficient to entice you to fetch your suitcase…and yes, that’s ONE suitcase, not two (packing lightly equals flexibility, but I’ve preached about this, many times).

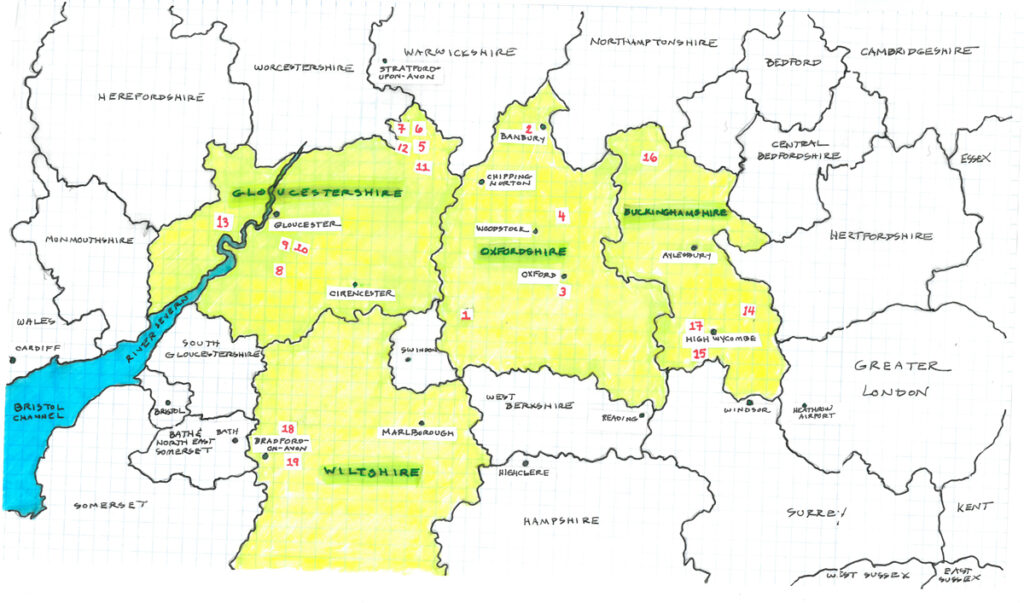

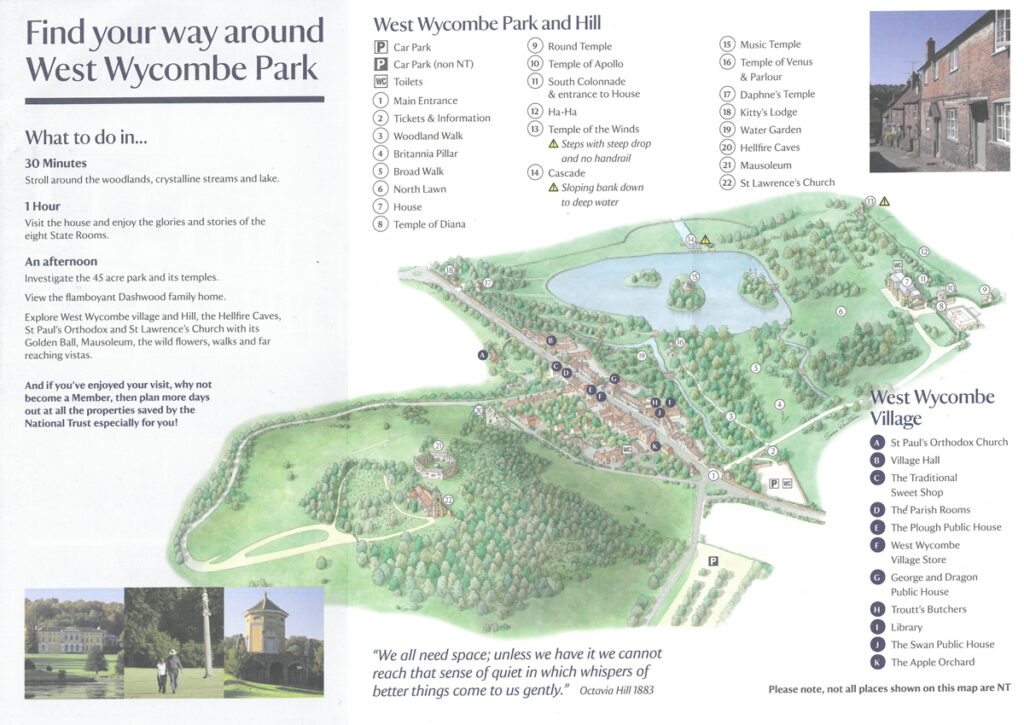

For an overview of our tour, yet another of my hand-drawn maps:

Key to Gardens: 1: Buscot Park. 2: Broughton Grange. 3: Oxford Botanic Garden.

4: Rousham House. 5: Bourton House. 6: Hidcote Manor. 7: Kiftsgate Court.

8: Miserden Park. 9: Painswick Rococo Garden. 10: Painswick St.Mary the Virgin Churchyard.

11: Sezincote. 12: Upton Wold. 13: Westbury Court. 14: Chenies Manor.

15: Cliveden. 16: Stowe. 17: West Wycombe Park. 18: The Courts. 19: Iford Manor.

![]()

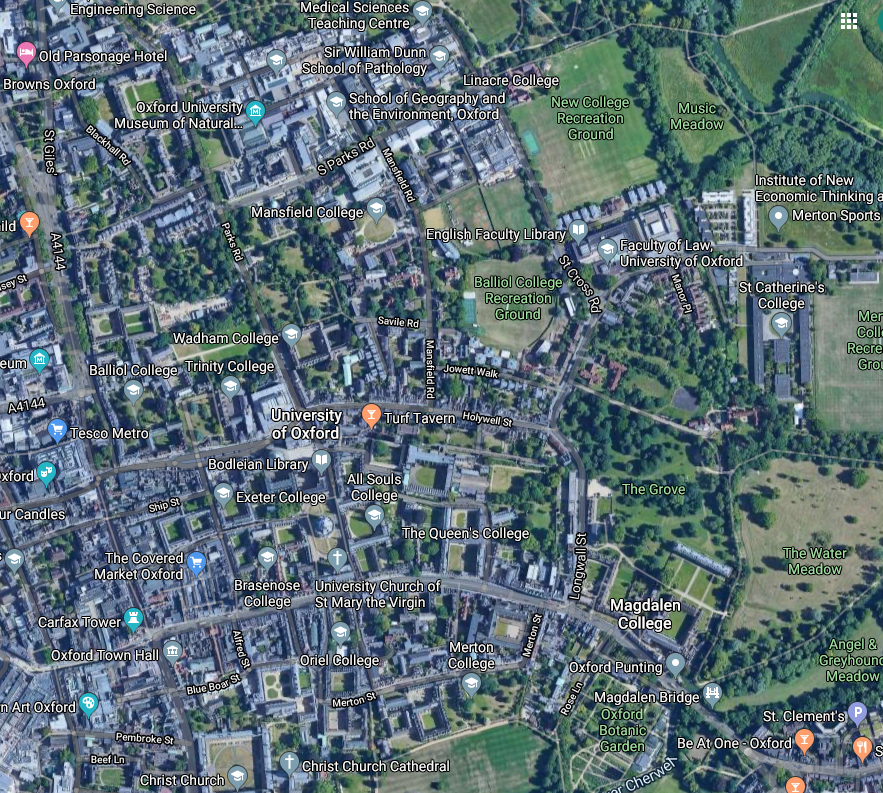

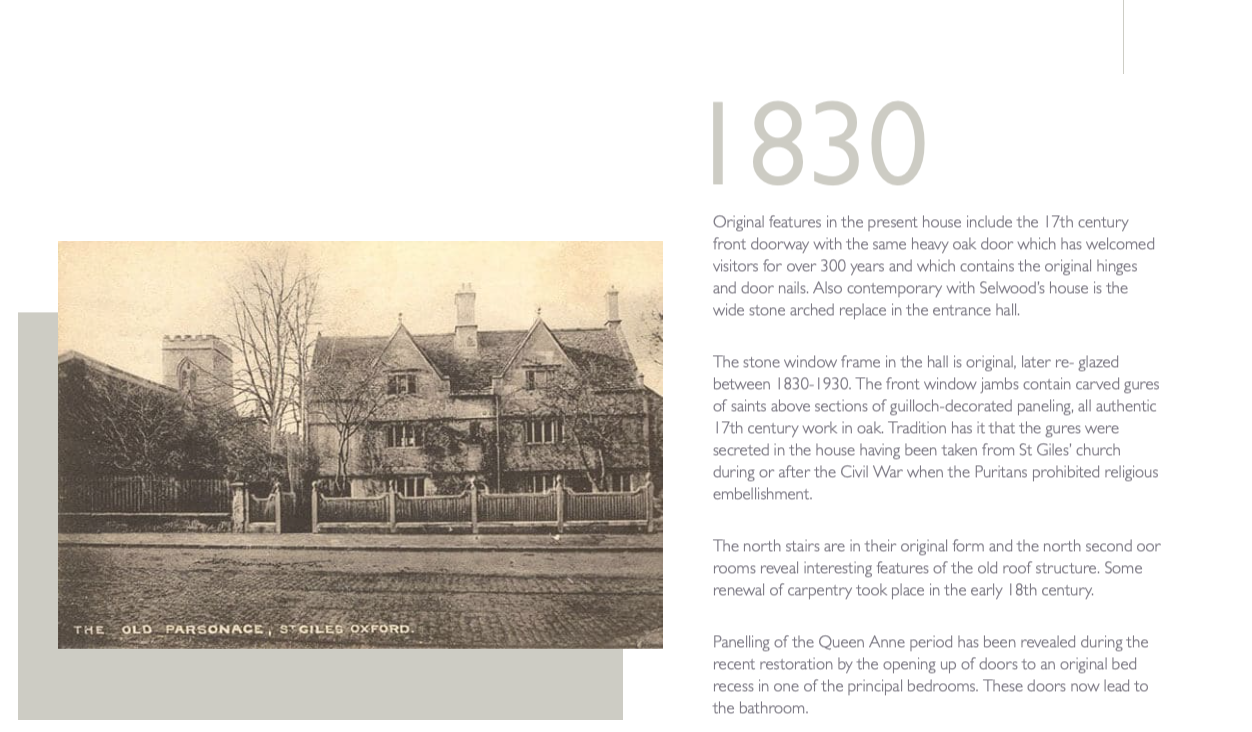

One of the ways I stay healthy during an extended time away from home is to choose a comfortable basecamp; my Own Personal Basecamp Nirvana has been achieved by staying at The Old Parsonage Hotel, in Oxford (which, for the purposes of this garden-tour, is also centrally located). The farthest-flung of the 19 destinations on my garden-map are no more than a 90 minute drive from Oxford (at least, on days when England’s Traffic Gods are smiling).

The Old Parsonage Hotel, 1-3 Banbury Road, Oxford OX2 6NN

Phone: 01865-310210

Image courtesy of the Old Parsonage Hotel

www.oldparsonagehotel.co.uk

Aerial View of central Oxford. The Old Parsonage Hotel is located

in the upper, left-hand corner.

Simply put: The Old Parsonage is the best-run Hotel I’ve encountered, in England.

In terms of design sophistication, location, dining rooms, amenities, and customer care, the Old Parsonage is operating at top-form. I travel a lot and so have much basis for comparison. In past visits to Oxford, I’d stayed at the Old Parsonage’s sister-hotel, the Old Bank (which is very nice), but during the summer of 2018 I decided to try the Old Parsonage, which I discovered to be a superior lodging-place. The Old Parsonage has two lovely outdoor dining terraces, a cozy indoor dining room, and a modern library and reading room which opens onto an elegant garden terrace. The core of the Old Parsonage was built in 1660, and the front entryway, which leads from the Banbury Road walled dining terrace into the Reception Hall, is still the same 358-year-old heavy oak door, complete with its original hinges and door nails. Various wings of the Hotel have been added over the centuries, but all areas of the structure have been totally restored or renovated, and are excellently maintained. If you’re an Oscar Wilde fan (and who isn’t?) you’ll be delighted to know that, during a time when he’d lost his rooms at nearby Magdalen College, Wilde is said to have sought refuge at the Old Parsonage, which rented lodgings to College undergrads. [Note: as always, there’s NO back-scratching going on here! I pay list price for my accommodations. Whenever I discover a superior Hotel, I’m happy to spread the news.]

A corner in the Lobby. Image courtesy of The Old Parsonage Hotel.

The ancient front door at The Old Parsonage Hotel. Image courtesy of the Hotel.

The roof terrace next to the Library at The Old Parsonage Hotel.

Image courtesy of the Hotel.

The Library at The Old Parsonage Hotel. Image courtesy of the Hotel.

Walled Front Terrace at The Old Parsonage Hotel. Image courtesy of the Hotel.

The view from my favorite room, at The Old Parsonage Hotel.

Image courtesy of The Old Parsonage Hotel

![]()

Let’s begin our garden visits. The gardens are listed within each of the four Counties.

Note: Open Days & Times vary. Please consult the websites of all Gardens, prior to

planning your trips.

![]()

GARDENS IN OXFORDSHIRE:

*Buscot Park & The Faringdon Collection

Faringdon SN7 8BU

www.buscot-park.com

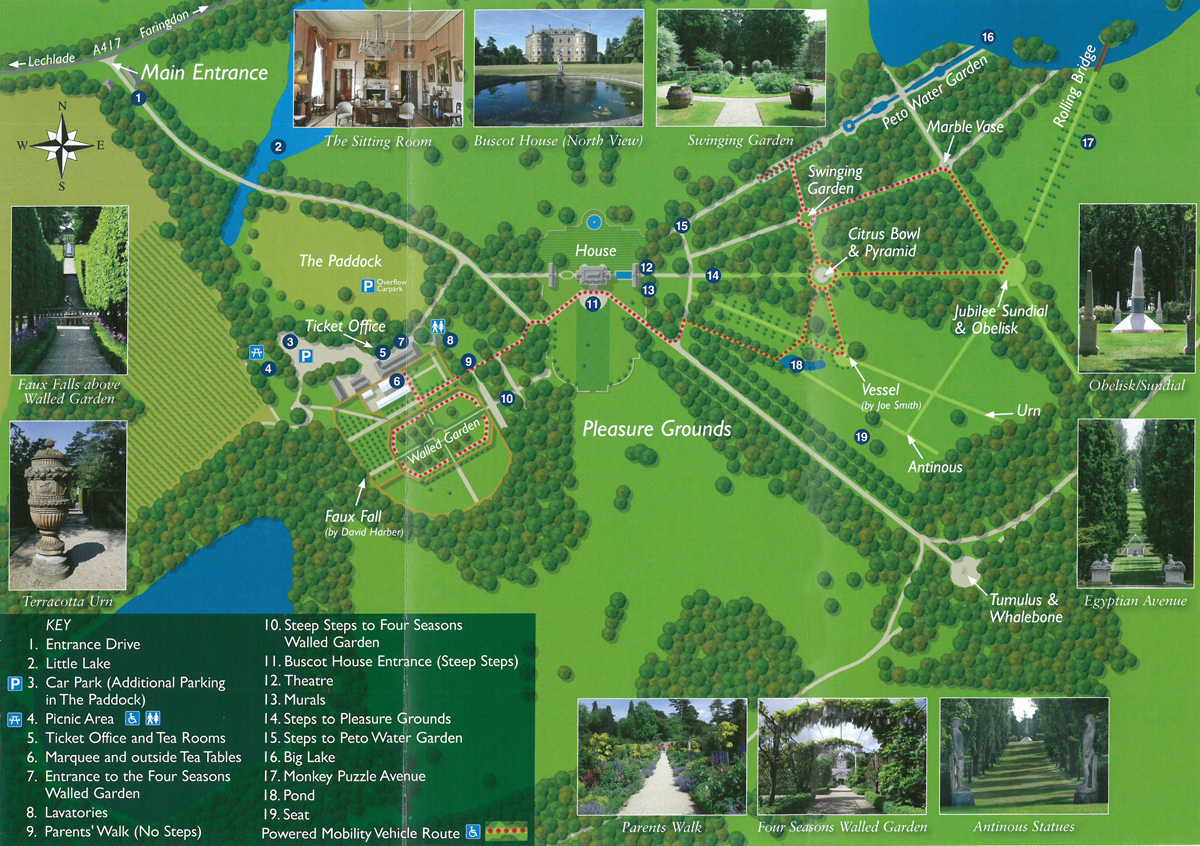

NQ’s Notes: An 18th century house (1780) surrounded by several hundred acres of parkland, complete with a 20 acre lake. Since the early 20th century, successive Lords Faringdon have commissioned the leading artists of their various eras to redesign and decorate the pleasure grounds. Buscot Park remains the family homestead of the current Lord Faringdon, Charles Henderson, but it’s opened to the public during the warm months of every year. Once you escape from the overpopulated Tea Rooms, you’ll have acres upon tranquil acres to explore. You’ll see Harold Peto’s world-famous 1904 Water Garden, and the parklands are decorated with a stunning array of art, ranging from ancient monuments to site-specific contemporary installations.

The owners of this monumentally grand estate clearly have

refreshingly UN-stuffy, eclectic, and forward-looking tastes.

Map of Buscot Park’s Pleasure Grounds

Fountain at the center of the lily pond in the Four Seasons Walled Garden. Since 1978, the vast, walled 18th century kitchen garden has been reorganized into quadrants, which are outlined by pleached hornbeams and Judas trees. Each section of the Walled Garden represents a different Season.

A quadrant of the Walled Garden

The step-free Parents Walk, to the north of the Walled Garden

During my June visit, the Walled Garden’s roses were perfect

In 2007 the artist and sculptor David Harber was commissioned by Lord Faringdon to make the Faux Fall. It consists of a series of highly polished steel vertical panels in graduated form and height, over which water is pumped. When viewed from the stairway on the opposite side of the Walled Garden, the Faux Fall appears to be a cascade. Image courtesy of Buscot Park.

The 17 lifesized Terracotta Warriors guarding the steep stairway

that leads from the Walled Garden up to the Pleasure Grounds are exact replicas of 5 different ranks of the Great Army, which was discovered at Lingtong, Xi’an, in the tomb of China’s first emperor, Ying Zheng.

A closer look at the Chinese Warriors.

We continue up the steep steps, toward the Pleasure Grounds

Pause. Turn around. Look back across the Walled Gardens, toward the mesmerizing Faux Fall.

Lord Faringdon’s Home is occasionally open to the Public, and holds the family’s collection of pictures, furniture, glass, silver, ceramics and objects d’art. Paintings include works by Rembrandt, Rossetti, Reynolds and Burne-Jones.

The Egyptian Avenue (which was completed in 2013) leads to the Citrus Bowl and Pyramid,

where an Italian wellhead is at the centre of a sunken circle that’s ringed by potted citrus trees.

Hovering above is the merest outline of a Pyramid.

The Pyramid. This skeletal structure was designed by David Harber.

Antionus Statues [Note: my Most Conscientious Readers will

recall—from my DIARY about Hadrian’s Villa— that Antionus was

the beloved of the Roman Emperor Hadrian.]

Obelisk/Sundial designed by Sir Mark Lennox-Boyd, to commemorate the Diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II

Another long Avenue, leading to the Pyramid

The Swinging Garden has a series of chain-suspended swings, hung around the perimenter of a sunny circle. Image courtesy of Buscot Park.

The Peto Water Garden at Buscot Park.

Image courtesy of Buscot Park.

Here’s what Buscot Park’s website has to say about The Peto Water Garden:

“Designed by Harold Peto, who was, in his day, the leading exponent of formal Italianate garden design, the Water Garden was laid out in 1904 for the 1st Lord Faringdon, and extended in a second phase of building in 1911 to 1913. The garden creates a link between the house and the Big Lake that is such an important feature of the original eighteenth-century parkland landscape. Consisting essentially of a chain of stairways, paths, basins and a central canal, the Water Garden is flanked by box hedges, sheltering statues and terracotta jars.”

“The stone-edged canal follows the bold linear axis of the earlier Victorian arboretum, carried for the greater part of its length through woodland. Variety is given to the design by a series of secretive enclosed lawns, surrounding rectangular and quatrefoil pools, and by effectively placed Italian marble seats and statuary. The canal stream is made to perform every possible manoeuvre before it reaches the lake, running over narrow rills and miniature cascades and beneath a hump-backed balustraded bridge. At one point the water is thrown into the air by the charmingly playful Dolphin and Putti bronze fountain. Water-lilies decorate the surface, and box hedges are flanked by stone figures on columns, and herms portraying Roman gods. Where it meets the lake, the vista continues eastwards to the domed and columned garden temple, also designed by Peto, which sits on the opposite shore.”

The final stretch of the Water Garden canal, which leads to the Big Lake.

Alongside the Water Garden canal, a Herm.

A huge curved bench, next to the Water Garden canal

Steps alongside the Water Garden canal

Our final view of Harold Peto’s Water Garden

![]()

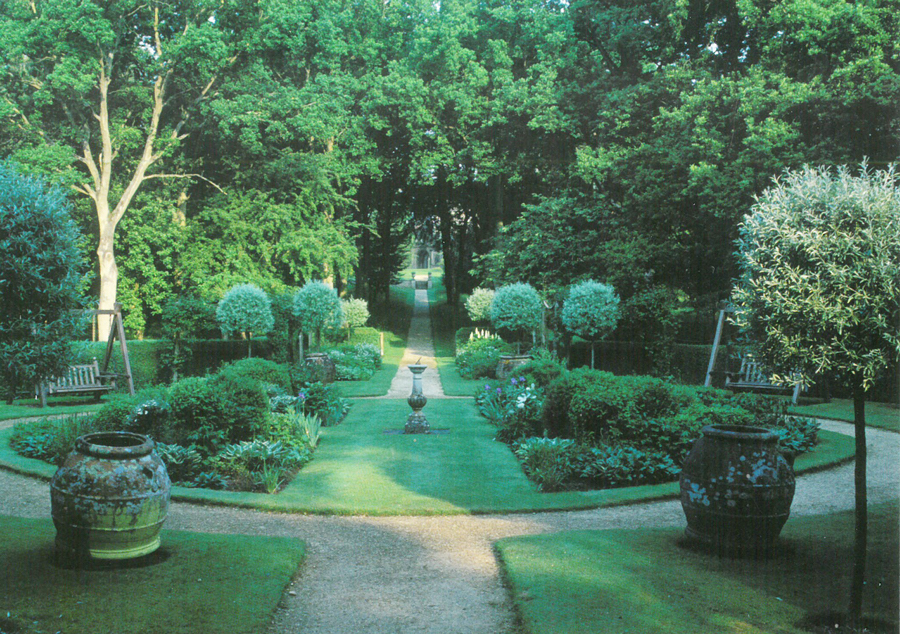

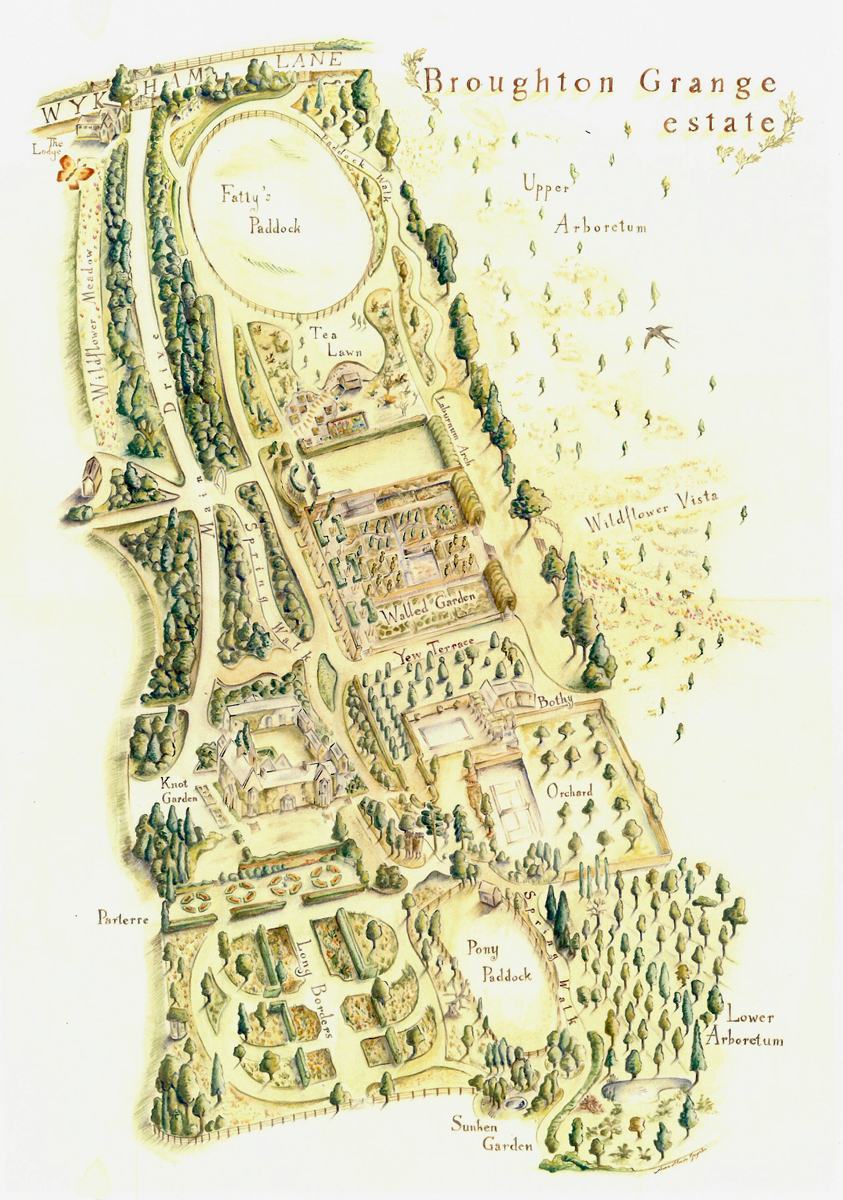

*Broughton Grange Gardens & Arboretum

Wykham Lane, Broughton, Banbury OX15 5DS

www.broughtongrange.com

NQ’s Notes: Begun in 2001, Broughton Grange has already become one of England’s best gardens. Voluptuous plantings, organized by dramatic swathes of color & combined with crisply-detailed hardscapes and boldly scaled water features, blend seamlessly in this design by Tom Stuart-Smith (a many-times Gold Medal winner at the Chelsea Flower Show). This is a garden where the heads-and-hearts of the gardeners are perfectly balanced; their planting schemes are simultaneously inventive and impeccable. Even when the gardens aren’t in full bloom, plenty of visual interest is provided by the

strong structural planting of beech, lime, and pencil yews, which complement the terraces, waterfall-fed pond, and geometric pathways. I’ll continue to visit this garden, whenever I’m based in Oxford. At Broughton-Grange we have the thrill of watching a first-rate garden evolve, from the ground up.

Map of Broughton Grange’s central gardens

We begin our garden-stroll in the Wildflower Meadow at Fatty’s Paddock.

Laburnum Tunnel

Leafy alcove, at the west end of the lawn that’s north of the Walled Garden.

Gate between the north lawn and the Walled Garden

Greenhouses are set against the north wall of the six-acre Walled Garden

Swathes of blossoms, on the upper section of the

Walled Garden

Just below the Walled Garden’s greenhouses, a canal leads to

a waterfall, which spills into a large fish pond that’s on a lower level.

Another path which begins near the greenhouses leads to the large fish pond

Waterfall and Stepping Stones

Koi

Another view of the Fish Pond

The Walled Garden’s Fish Pond is situated above the Leaf-Cell-Structure-Parterre

We’re in the Leaf-Cell-Structure-Parterre, and are looking

uphill, back towards the greenhouses.

Beyond the Leaf-Cell-Structure-Parterre we see the sculpted

Trees on the Yew Terrace

Another view of the Yew Terrace, as seen from the lower

Path in the Leaf-Cell-Structure-Parterre

The eastern edge of the Parterre is defined by a tall green tunnel. Beyond the tunnel, a new, 80-acre arboretum is being planted.

Downhill from the Yew Terrace is the Spring Walk,

in the Lower Arboretum. I paused to admire (but not touch…) this sharp-needled Monkey Puzzle Tree.

Further along the Spring Walk is the Stumpery (a peculiarly-British garden style which uses uprooted tree stumps as ornaments)

We’re at the lowest end of the central path that rises through the Long Borders. This grassy slope links the surrounding sheep meadows with

the Main House (still occupied by the owners of the Estate).

At the top of the central Long Borders path

A traditional Parterre is just above the Long Borders.

Stepping away from the traditional Parterre, I take in the glorious English countryside.

![]()

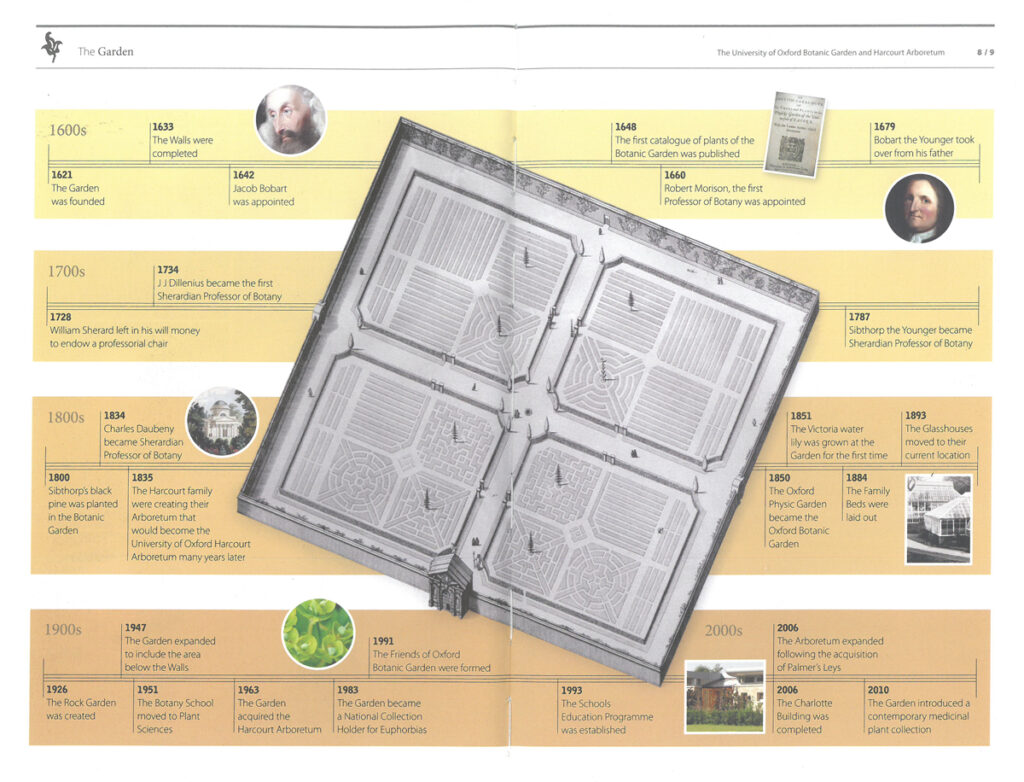

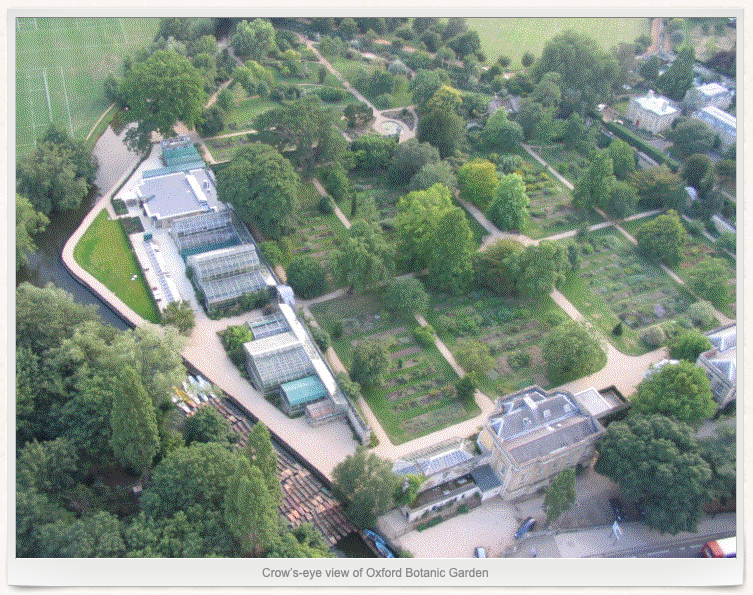

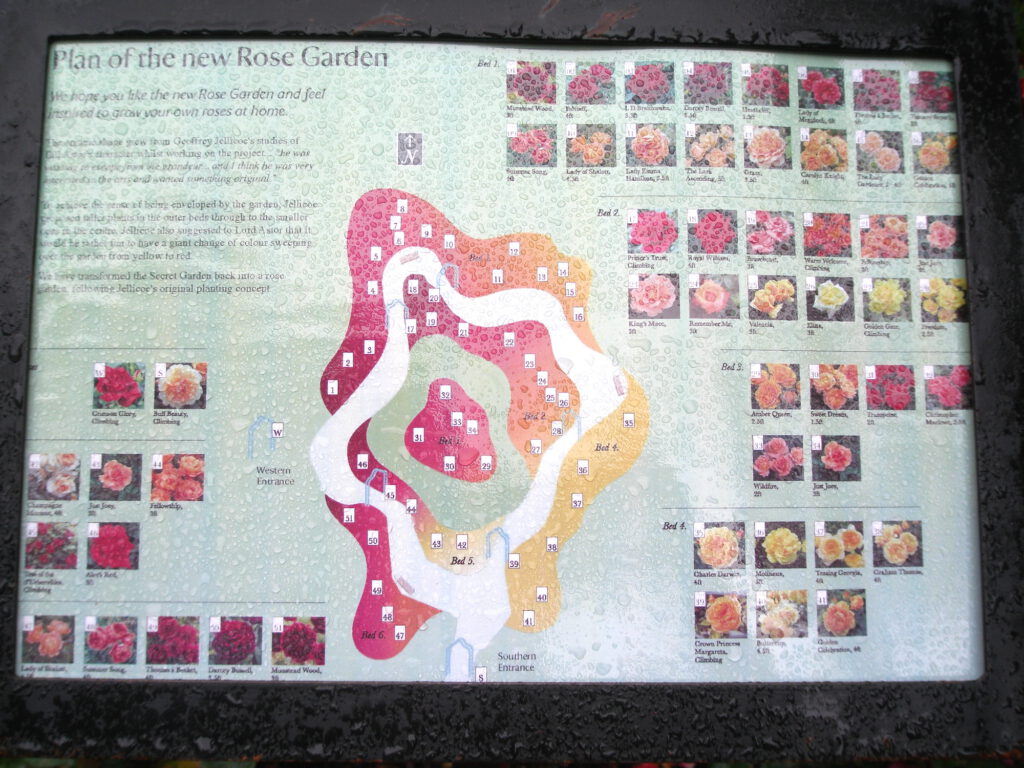

*Oxford Botanic Garden

Rose Lane (by the Magdalen Bridge)

Oxford OX1 4AZ

www.botanic-garden.ox.ac.uk

NQ’s Notes: Founded as a physic garden in 1621, Oxford University’s Botanic Garden has evolved into a collection of over 7000 types of plants. The Garden’s 3 areas (the Glasshouses, the Walled Garden, and the Lower Garden) present us with one of the most bio-diverse little plots of land in the world. Go at opening time (10AM) to best experience this wonderful City Oasis. Each garden bed is labelled (bring camera and notepad and LEARN) and the friendly gardeners are always happy to speak with Visitors. And, for Philip Pullman fans: find the bench (set in the Lower Garden, near the Orchard and the River Cherwell) where Lyra and Will said their farewells in THE AMBER SPYGLASS.

Map of the Oxford Botanic Garden

How the Garden has evolved. Image courtesy of Oxford Botanic Garden.

An imposing bell tower, just across the High Street from the Botanic Garden, is a reminder that you ought also to visit the grounds of Magdalen College, where you’ll enjoy elegant courtyard gardens, canal-side gardens, and a woodland walk which encircles the improbably huge Deer Park.

Aerial view of Magdalen College’s grounds.

Highlights of the Oxford Botanic Garden:

In the Walled Garden: Taxonomic Garden Beds, with the tower of Magdalen College in the background

The Walled Garden’s central fountain, with the Danby Arch in the background

Danby Arch, with the busy High Street just beyond the gate

The Walled Garden’s

Consevatory. Image courtesy of Oxford Botanic Garden.

Glasshouses by the River Cherwell

The Rainforest Glasshouse

Inside the Water Lily Glasshouse. Image courtesy of Oxford Botanic Garden.

The Lower Garden’s Herbaceous Border

In the Lower Garden: Fruit, Herb, & Veggie beds.

The Lower Garden’s Water Lily Pond is surrounded by Rock Gardens. Farther back in the Lower Garden we see the tall grasses of the Merton Borders.

The Merton Borders were planted nearly 10 years ago.

Per the Botanic Garden:

“The Garden worked in collaboration with Professor James Hitchmough from the Department of Landscape Architecture at the University of Sheffield to develop the sustainable Merton Borders. The borders occupy an area of 955m2, and are an example of sustainable horticultural development, with the aim of having minimal impact on the environment in the long term.

The planting is based on an ecological study of natural plant communities to produce an ornamental yet sustainable display. 85% of the plants were established through the direct sowing of seed. This has two benefits: firstly, it is more sustainable than planting thousands of plants grown in peat-based composts and plastic containers. Secondly, sowing from seed makes it possible to establish plants at much higher densities. This increases the diversity of the plantings, and ensures a long succession of flowering through the season.

The plants have been selected for their ability to withstand drought conditions and originate from seasonally dry grassland communities in three regions of the world:

• The Central to Southern Great Plains (USA) through to the Colorado Plateau and into California

• East South Africa at altitudes above 1000m

• Southern Europe to Turkey, and across Asia to Siberia

Selecting plant species from these drier plant communities will build in a greater tolerance of warmer, drier summers.

The planting is colourful from spring to autumn, and represents a dynamic style of planting. It is also drought-tolerant, requiring no artificial irrigation, staking or fertilisers. It is allowed to die back over a long period after the autumn, providing a rich habitat for many types of small birds and mammals.”

The River Cherwell, at the east end of the Merton Borders

Central path through the Merton Borders (we’re looking west)

In the Lower Garden: a small Orchard is next to the River Cherwell

Near to the Bog Garden (in the Lower Garden): our long view back down the central path of the Botanic Garden.

The Lower Garden’s Autumn Border. Image courtesy of Oxford Botanic Garden.

![]()

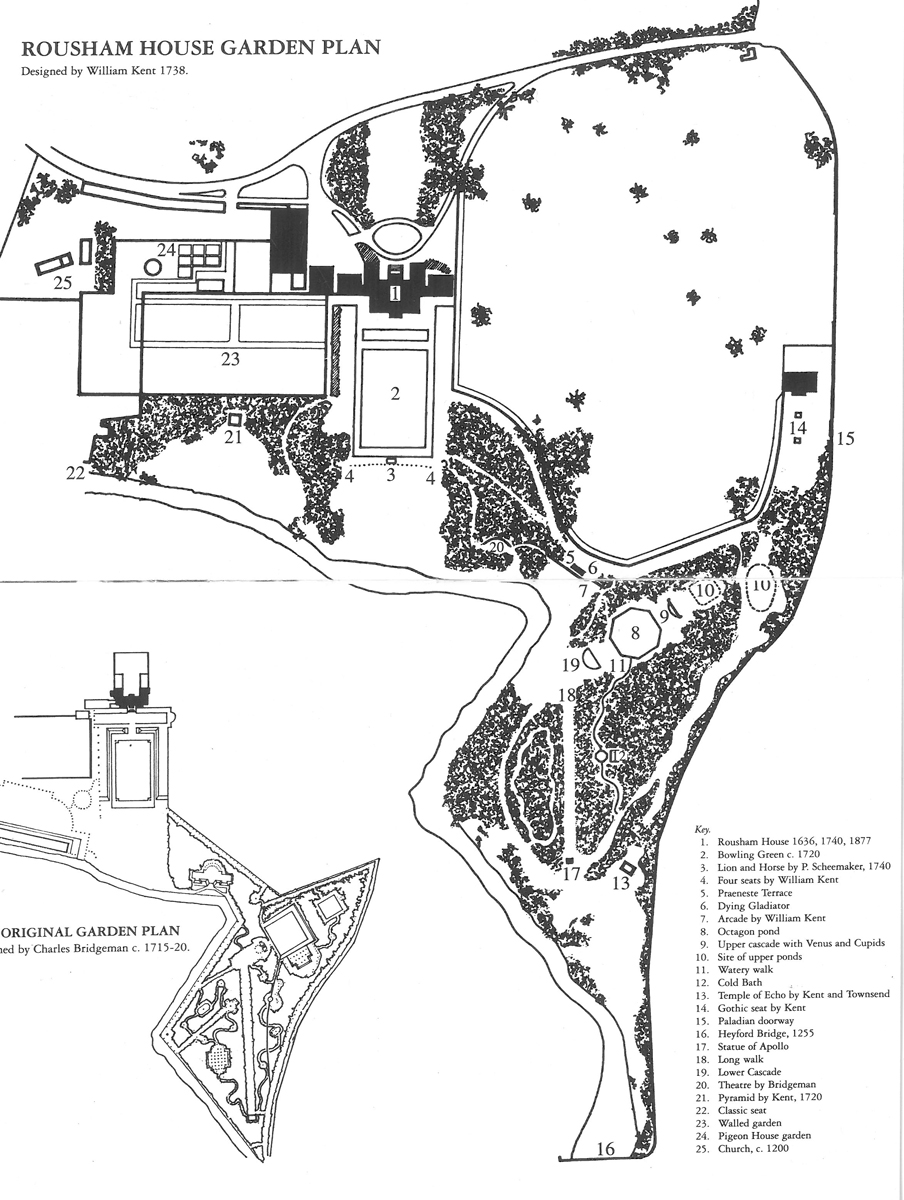

*Rousham House & Garden

Rousham, Bicester OX25 4QX

www.rousham.org

NQ’s Notes: These gardens still look very much as they were designed to be in 1738 by William Kent, when he substantially revised and enlarged the original garden, which had been laid out between 1715–1720 by Charles Bridgeman. This miraculous feat of garden preservation is due entirely to the Cottrell-Dormer family, whose descendants have lived continuously at Rousham since 1635, when the first house was built on 25 acres of rolling pastureland in the Cherwell river valley.

The Cottrell-Dormers understand the enormous cultural significance of their estate, and generously open the grounds to the Public, 365 days a year, from 10AM until dusk. There’s no Visitor Centre: find the ticket machine, feed your 8 Pounds into a slot, and the sublime parklands and gardens can then be yours for the day. Dogs and children (under 15) aren’t allowed, but your picnic baskets are. Just THINKING about Rousham lowers my blood pressure.

As you explore this extraordinary and hugely important example of an Augustan Landscape Garden, you’ll feel you’ve traveled

nearly 300 years into the past. Rousham is my favorite garden in England.

Rousham Park Map. In its essentials, we’ll see the garden as it was laid out to be, in 1738.

Aerial View of Rousham Park

Whenever I’m based in Oxford, I spend a morning at nearby Rousham. I have yet to inhabit these gardens on a sunny day, but

have come to adore my rainy day visits. All of my photos were taken during inclement weather. (On a stormy day, wear waterproof boots with good traction; you might find yourself sloshing along pathways covered with seriously-18th- century-quantities of MUD.)

Rousham House. The south side. The house was built in 1635, with mullioned windows and gables. In 1738 the multitalented William Kent (Architect & Painter. Designer of Landscapes, Interiors, Furniture & Book Illustrations) enlarged and transformed the house into what the

current owners call “something vaguely resembling an Early Tudor palace in free Gothic style.”

Detail of the north façade of a projecting wing which was added to the House in 1860.

Charles Cottrell-Dormer has created a booklet for Visitors about his magnificent home. Here, for some necessary context,

some passages from that publication:

“In 1738, the gardens were remodeled by Kent, who laid out the slope down to the Cherwell on the north side, and ornamented the grounds with terraces, statues, and buildings in the Italian taste.

The original plan appears to be by Charles Bridgeman, who also laid out Kensington Gardens and Stowe. Kent’s plan was described as ‘a rarity, an organic yet disciplined design, applying order loosely, yet lucidly, to a slice of English country, achieving an effect crystalizing Nature.’

Many of the features which delighted 18th century visitors to Rousham are still in situ, such as the cascades and ponds in Venus’ Vale, the Cold Bath with its elaborate waterways, & the seven-arched Portico known as Praeneste.

The relationship of the layout to the charming view over the Cherwell valley aptly illustrates Addison’s vision of ‘a whole estate thrown into a kind a garden;’ and although the parts are formal, the irregular intricacy of the plan, with its sylvan glades and classic features, goes far to confirm Kent as the father of the English art of landscape design.”

Let’s begin our tour of the Gardens:

The Bowling Green

(c. 1720), and the north façade of the House

A massive Drunken Hedge made of ancient yews parallels the east edge of the Bowling Green

Another view of the Drunken Hedge. The tunnel through the yew hedge is 20 feet deep and leads to the enormous Walled Garden

We’re about to enter the Walled Garden

Double Flower Borders are planted along the entire length of the southern edge of the Walled Garden.

A rose-covered arbor and pool are at the center of the Walled Garden. Most of the Walled Garden continues to be a working garden, where fruits and vegetables are grown.

South of the Walled Garden: the Pigeon House Garden

The Pigeon House was built in 1685

I’m inside of the Pigeon House (along with many pigeons)

The revolving ladder inside the Pigeon House

Just east of the Pigeon House: a Church (c.1200) and a blooming Smoke Tree

West of the Bowling Green, and beyond a ha-ha, long-horned cattle graze. In the distance the pediment of Kent’s Palladian Doorway is visible.

At the north edge of the Bowling Green: a Lion & Horse sculpture, by P.Scheemaker, 1740. At the bottom of the grass slope we see the narrow channel of the Cherwell.

Farther into the Gardens, there’s a Dying Gladiator (also by Scheemaker). The balustrade behind him is mounted on the roof of the Praeneste Terrace, an arcade which is embedded into the slope

which overlooks a 90 degree bend in the Cherwell.

My view of the Cherwell, from above the Praeneste Terrace’s roof-mounted balustrade. Next to the River, I see the only other Soul who was there in the Gardens, on that rainy morning. This is my idea of Garden-Touring-Heaven.

The Praeneste Terrace

River view, from the Terrace

Sheltered from the rain, in the Praeneste Terrace

Bench, designed by

William Kent

River view, from the Terrace

View up to the Terrace from the grass path alongside the Cherwell

Lower Cascade: originally enlivened by a waterfall & fountains

View of the Praeneste Terrace and the Lower Cascade

Octagon Pool and Upper Cascade

Upper Cascade. This is the Vale of Venus. Her Swans were originally ridden by cherubs, and fountains once created clouds of mist

that swirled around her.

A Long Rill empties into the Octagon Pool. We follow the Rill uphill, along the Watery Walk.

When I first encountered this Rill, I was certain that it could not possibly be original to the Gardens. The space feels utterly 21st century ! When I got home, I emailed Charles Cottrell-Dormer for a clarification. Mr. Cottrell-Dormer’s prompt reply: the course of the Rill was set by Charles Bridgeman, and William Kent added stone

edging to the sides of the Rill. In my humble opinion, The Rill and Cold Bath and Watery Walk form an environment which is so perfect that it exists outside of time.

At the mid-point of the Watery Walk’s Rill, we find the Cold Bath.

On the west edge of the Cold Bath, a grotto is set into the hillside.

We’ve reached the high end of the Rill, and approach the Temple of Echo

The Temple of Echo

At the nearby statue of Apollo, I look southwards, down along the leafy tunnel of the Long Walk

We head back towards the Praeneste Terrace, along the curving Lime Walk, which lies just above the Cherwell.

Our visit to Rousham Park almost completed, we follow a narrow track above the ha-ha, which leads to Kent’s Palladian Doorway& Gothic Seat.

The Palladian Doorway & Gothic Seat. Kent meant the Palladian Doorway to be the main entrance for Visitors to the Gardens.

Our View from the Palladian Doorway, across pastureland, to Rousham House. This is the vista which William Kent wanted garden Visitors to first see.

After retracing our steps alongside the ha-ha, we arrive back at the Bowling Green

A beautiful and diabolical gate, by the ha-ha

We admire Rousham’s lichen-covered stones, and the single palm tree in a pocket garden by the House’s conservatory.

As we take our leave of all of this Grandeur, Hens pecking for insects on the front drive bid us adieu.

![]()

GARDENS IN GLOUCESTERSHIRE:

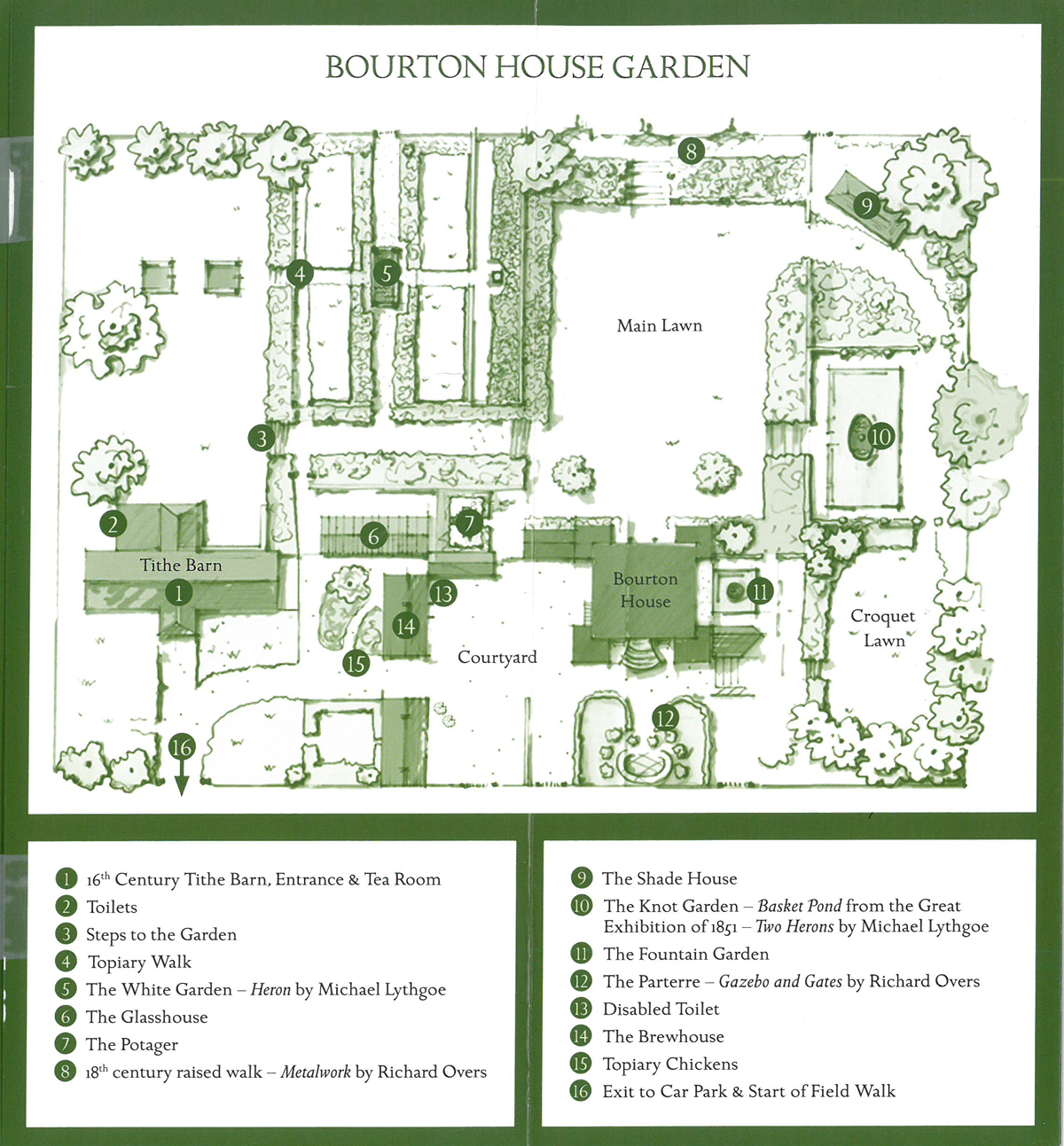

*Bourton House Garden

Bourton on the Hill, GL56 9AE

www.bourtonhouse.com

NQ’s Notes: Since Saxon Times, various grand houses have occupied this site. The charming 3-acre gardens you see today were begun in 1983, and they surround a Jacobean manor house. In contrast with the other enormous estates on my Very Best List, Bourton House is almost a Pocket Garden. But every corner of this little garden is overflowing with exuberance, horticultural excellence, and creativity. Though compact, there are so many design-details here to savor that I’ve always lingered for several hours.

Plan of Bourton House Garden

On our way to the Garden from the Parking Field, we discover this toy soldier whirligig.

After crossing the Tithe Barn’s Lawn, we enter the Garden.

The White Garden, with Heron sculpture by Michael Lythgoe

Topiary Walk. My most recent visit to Bourton House was in July 2018, when England was suffering from a drought . British gardeners become very tetchy when their lawns aren’t emerald green, and so Burton House’s gardeners were most apologetic about the scorched grass.

An urn in the White Garden

Precisely-clipped Topiary cast wonderful shadows

More elegant examples of Topiary

Yet another refined display in the White Garden

The Potager

The Potager and House

View of the House, from the Raised Walk that separates the Main Lawn from surrounding pasturelands.

The Red Border by the Main Lawn

At the center of the Raised Walk, a bench/pergola by

metalsmith Richard Overs

The Shade House

Borders near to the Raised Walk

The Knot Garden

The Knot Garden, with its spring-fed Basket Pond. This vessel is from the Great Exhibition of 1851 (also called the Crystal Palace Exhibition).

The Knot Garden

Bench at the shady end of the Croquet Lawn.

I WANT this Bench!

The Fountain Garden

The Parterre: Gazebo by Richard Overs. Just beyond the stone wall is a steep, country road. On the other side of the road is Bourton House’s 7 acre Field Walk, where many fine specimen trees can be admired.

![]()

*Hidcote Manor Garden

Hidcote Bartrim, near Chipping Campden GL55 6LR

www.nationaltrust.org.uk/hidcote

NQ’s Notes: Because Hidcote suffers from Industrial Strength Tourism

(endless arrivals of coaches, overflowing with garden lovers who’ve traveled there from Earth’s farthest reaches)

this place is not one of my favorite destinations. But, despite being mobbed, due diligence requires that we visit. Along with Sissinghurst, in Kent, Hidcote is one of most renowned gardens created in England during the 20th century.

In 1907, the wealthy American expatriates Lawrence Johnston and his mother Gertrude Winthrop made an offer to buy a 17th century manor house, along with 287 acres in the Cotswolds. 7200 British Pounds sealed the deal, and Lawrence busied himself with house renovations and also began to accumulate rare plants. To create settings for his horticultural collections, Johnston then built greenhouses, terraces, walls, gazebos, bridges, ponds, streambeds, paths, and steps. He seeded lawns, fenced in paddocks, and planted trees, hedges, flowers, and vegetables.

Everything we see today at Hidcote is maintained to the same exacting standards which applied during Johnston’s lifetime. Hidcote’s layout is maze-like; from no vantage point can the entirety of the landscape be understood. Each space seems a place unto itself, and wandering from one area into another is sometimes disorienting. But the constant element of surprise holds the design together, and the lushly-planted grounds present a master-class in flower-bed color-blocking. Were it not for the crush of garden-globetrotters, Hidcote would be a lovely place to spend the afternoon.

The illustrations which follow are intentionally deceptive because they do not include hundreds of humans. My photos resulted from patience: I’d wait for clusters of visitors to disappear from view. For parts of the garden where my patience wasn’t rewarded, I’ve borrowed pictures from designer Anne Guy, or from Hidcote’s website.

The gables of the Manor House: a dramatic background for the Garden. Photo courtesy of garden designer Anne Guy

Between the House and the Old Garden: a Cedar of Lebanon, which is original to the property.

The Old Garden. Photo courtesy of Hidcote

The White Garden. Photo courtesy of Hidcote

The White Garden

View from the Old Garden toward the Red Borders. Photo courtesy of Hidcote

The Red Borders. Photo courtesy of Anne Guy

Approaching the Fuchsia Garden

Hidcote’s famous Topiary Birds and Yew Arch: between

the Bathing Pool Garden and the Fuchsia Garden. Photo courtesy of Anne Guy

A corner of the Fuchsia Garden. Photo courtesy of Anne Guy

Central Stream Garden

My view of a Gazebo in the Red Borders Garden, & the Central Stream, as I stood at the lowest point on the Long Walk

The beginning of the Long Walk

The Beech Alley

View of the Pillar Garden, as seen from the Alpine Terrace.

Photo courtesy of Hidcote

View from the Rock Bank, out over Sheep Meadows

![]()

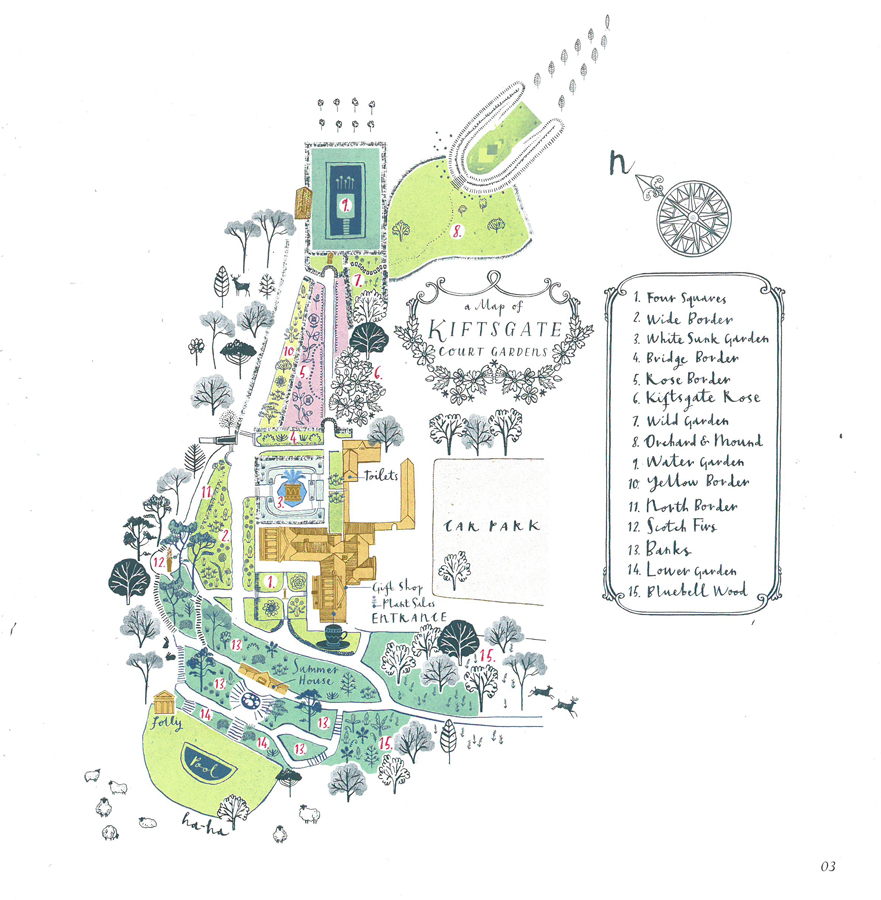

*Kiftsgate Court Gardens

Chipping Campden GL55 6LN

www.kiftsgate.co.uk

NQ’s Notes: Literally across the road from the madhouse of Hidcote you’ll find an entirely different world at Kiftsgate Court.

These tranquil 100-year-old gardens surround the home of Anne Chambers. You’ll marvel at the voluptuous blossoms and verdant greenery, stunning views, and bold landscape architecture. The older areas of the gardens are laid out in formal style, but are softened by cascades of flowers, which include many varieties of peonies and roses. Three generations of self-trained women gardeners have created Kiftsgate. In 1919 Heather Muir began to make gardens for the manor house (which was built in 1887-91); as she undertook this massive project she was encouraged by her friend and neighbor, Lawrence Johnston. During the 1960s, Heather’s daughter Diany Binny expanded and modernized the gardens. In the early 1980s, Diany’s daughter Anne Chambers took over, and since then she and her husband have made additions which they hope will “reinvigorate and enhance the garden well into the 21st century.”

The most recently developed areas include mesmerizing water features and landform art, and intriguing pieces of sculpture dot the grounds. Throughout, the horticulture is first-rate (and envy-inducing). The lay of the land varies widely, and thus bestows surprising views and extra dynamism upon an eclectic sequence of spaces: the gardens cling to steep hillsides, ramble through dappled woodlands, lounge upon terraces, and stretch across rolling pasturelands. Kiftsgate Court is one of the gardens in England which continues to evolve in ways that make my heart sing.

Plan of the Gardens at Kiftsgate Court

Aerial view of Kiftsgate Court Gardens, which sit on top of the Cotswold Escarpment.

Having just entered the garden, we’re given NO hint of the surprise that awaits us.

Reaching a Terrace that’s adjacent to the southwestern edge of the Four Squares Garden, we peer down a steep slope through a grove of towering Monterey pines, and are presented with this spectacular vista, across the village of Broadway and the Vale of Evesham, and further out

towards the Malvern Hills, to the west.

But before we clamber down the many flights of steps that lead to this enticing half-moon pool, we’ll explore the garden that is closest to the House.

A view of the House, from the grass path of the Wide Border.

Above steps, a sundial is mounted in the center of the Four Squares Garden.

The Four Squares Garden’s beds are edged in box. Clumps of peonies show well with the different leaf textures of salvia candelabrum and Buddleja crispa. The pink roses have a blue strain running through them: a favorite is Rosa Rita, which was planted in the 1960s.

Peonies in the Four Squares Garden, during my visit in June of 2014.

The North Border. A Pagoda Dogwood creates a living archway over the long path.

Columbines on the North Border

Below the North Border, we discover a steep flight of steps. We descend through a grove of Scots Pines, and see Mother & Child, a statue by Simon Verity.

Per Kiftsgate’s garden Brochure: “In the 1930s the steep banks to the southwest of the house were tackled. Italian gardeners terraced them and a summerhouse was built with steps descending to the lawn below.”

We’ve reached the Lower Garden, and the Half-Moon-Swimming-Pool. The pool was built by Diany Binny in the 1960s.The Lower Garden is a protected spot; warmer than the other areas

at Kiftsgate. Exotic plants such as echium which cannot usually be grown in the Cotswolds survive in this setting.

A Folly, in the Lower Garden

Another look at the Half Moon Pool. A ha-ha runs along the outer curve of the raised grass platform of the Lower Garden. Below are acres of pastureland.

Halfway up the slope of the Banks Garden is a little summerhouse, designed by Heather Muir. The summerhouse is

surrounded by plants which are native to the Mediterranean.

Sinuous steps connect the Lower Garden and the Summerhouse

We’ve returned to the top of the hill, and now admire the Wide Border.

Our view of the Wide Border, from the Four Squares

Mid-way along the central path of the Wide Border.

Sculptural Hedging, on the Wide Border

The White Sunk Garden. The wellhead in the central fountain comes from the Pyrenees.

Over the years, flowers of many colors have been introduced into the Sunk Garden, which was originally a white garden.

More COLORS in the Sunk Garden

A vivid blue door

( I covet this door ), at the rear of the Sunk Garden.

A Copper Beech Hedge separates the Sunk Garden from theRose Border.

At the opposite end of the brick path through the Rose Border, we pass under an archway of clipped whitebeam, into a secret garden.

Sculptor Simon Verity was commissioned by Diany Binny to make this statue seat out of two tomb stones.

Next to the statue seat a clair-voie has been

cut through the hedge. From this spyhole we see the Water Garden, which in the late 1990s replaced an old tennis court.

The Water Garden

Anne Chambers explains: “For some years we had looked for an opportunity to add our own mark the the garden. When the surface of the hard tennis court started to break up, we decided in the late 1990s to design a water garden that reflected our own enjoyment of contemporary design and materials. Our starting point was the existing mature yew hedge. A rectangular pond now covers the area of the doubles court. This is surrounded by slim white paving stones which contrast well with the black water.”

“The sculptor Simon Allison answered our request to design something that provided height and movement by producing twenty-four stainless steel stems topped with gilded bronze leaves moulded from a philodendron. They sway gently in the wind and reflect well in the dark water. The sound of water dripping off the leaves provides refreshment on a hot afternoon.”

Detail of the bronze leaves of the fountains in the Water Garden.

Kiftsgate’s newest section lies beyond the yew hedge which runs along the east side of the Water Garden. An Orchard path leads to steps which bring us to the Mound, and then to the long Avenue, which, from a distance, seems to lead us into the sky.

This horseshoe-shaped Mound was constructed using the 1000 tons of soil which were excavated to form the Water Garden. When I took this photo on July 4, 2018, yet another drought had scorched all of England’s lawns.

Per Anne Chambers: “The edge of the Mound has been planted with a hedge of rugosa roses. From here a lovely view awaits you up the tulip tree Avenue, to the stainless steel leaf sculpture by Pete Moorhouse. The veins of the leaves are replaced by an Islamic pattern. Inside the Mound, coloured stones are formed in a chevron pattern and four olive trees in planters lead your eye to the far end of the Avenue.”

Another view of the Mound

Leaf Sculpture by Pete Moorhouse

I head downhill , away from the Leaf Sculpture, back toward the Mound

Before I leave these gardens, I pause for a long while, to once more savor this incredible panorama.

![]()

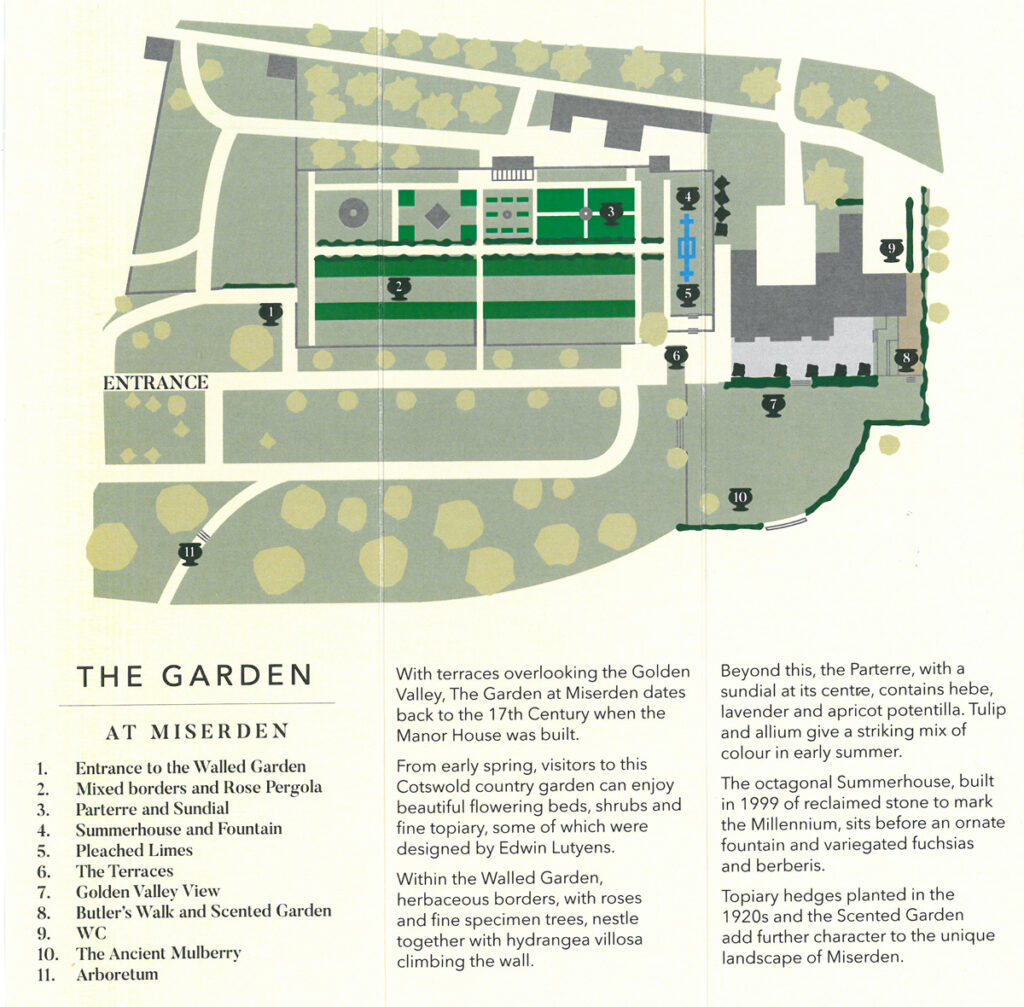

*Miserden Park Gardens

Near Stroud GL6 7JA

www.miserden.org

NQ’s Notes: These gardens—–which aren’t huge but FEEL huge—have simple, rectangular layouts that date to the 17th century. Set upon a hilltop overlooking a pretty arboretum, the garden’s virtuosic combinations of variegated and colored-leaf trees and shrubs, as well as its sculpted hedges, a dramatic yew walk designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens, gorgeous terraces, flights of grass-steps, and clever decorative flourishes, make Miserden Park an inspiring destination. Because the gardens have only been opened to visitors for a few years, the place (a family home) still has that “Serene-and-Not-Yet-Tainted-By-Tourists-Vibe,” which I cherish.

Plan of the Garden

at Miserden

Blink and you’ll miss it (I did….twice). But YES,

this is where your visit to the Garden at Miserden must begin.

As I made my way toward the Garden, I was delighted to see the Arboretum

An entrance on the side of the Walled Garden

Mixed Borders, with a dramatic backdrop of the carved hedges designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens for his Yew Walk

Sir Edwin Lutyens (born 1869, died 1944)

On the Mixed Borders, I was kept company by this gardener (wearing a pink shirt) who was working, near to the Rose Pergola

The Rose Pergola

Midway along the Mixed Borders broad grass path, we look down the cross-wise path that pierces Lutyen’s Yew Walk, and then leads to a Parterre, and finally to a cluster of rustic, stone cottages.

Just below the Mixed Borders, we find the House and Terraces

The wall between the Mixed Borders and the sloping Arboretum comes to a definitive HALT, where this Sycamore tree has

insinuated itself into the stones.

From the Terraces: our view of the Golden Valley

Below the Mixed Borders and adjacent to the House are

the Rill, Fountain, and Summerhouse

A closer look at the Rill, Fountain and Summerhouse

Looking back up the gentle slope, we have a wide view of the

Mixed Borders, Lutyen’s Topiary Yew Walk, and the Parterre

The ornate gate to Lutyen’s Topiary Yew Walk

Lutyen’s Topiary Yew Walk. This ribbon of monochromatic space, with its exaggerated proportions—a narrow grass floor and very high walls of greenery—is an initially unsettling but ultimately exciting place to be!

Just below the Sycamore tree, a broad flight of grass steps

Our view of the grass steps, Sycamore tree, and

the Pleached Limes which are at one end of the Rill-lawn

Below the House’s Terrace: Yew Topiary with an embedded Urn (one of the most ingenious examples of garden-décor I’ve seen).

This side of the house is an expansive wing that was added by

Lutyens. He also designed the wide terraces, the geometrically-pruned yews, and many wisteria trellises.

An avenue of golden foliage beckons

Another flight of grass steps leads us down from the Terraces

This path leads to the Scented Garden and Butler’s Walk

Hermes points the Way.

A gate on the Butler’s Walk: an elegant display of recycling.

We head back uphill, via stone steps which lead to the Terrace. This garden is bursting with sophisticated displays of variegated and colored foliage.

The Sundial and Parterre, with Lutyen’s Yew Walk as backdrop

As I head for the vegetable plots and orchard, I pass this

Quintessence of a Cottage Garden.

![]()

*Painswick Rococo Garden

Gloucester Rd, Painswick, Stroud GL6 6 T H

www.rococogarden.org.uk

NQ’s Notes: With a design dating from the 1740s, this is the only example in England of the short-lived fashion (from 1720—1760) for making gardens in the Rococo-manner. The gardens we see today have been restored, using as a Guide the realistic painting made of them in 1748. Painswick’s gardens deserve to be seen because they are an Historic Curiosity; their hodgepodge of features

don’t conform to the notions of other eras about how grandly-scaled ornamental gardens ought to appear.

Per the Rococo Gardens guidebook:

“Gardens at the beginning of the 18th century were starting to change.

Previously they were formal and regular in design and tended to be close to the dwelling. By the middle of the century they were developing on a much grander scale, incorporating or even changing the local countryside. The ‘English Landscape Garden’ had been born. The

Rococo period was part of this transition.”

“Rococo gardens captured the aristocratic and pleasure seeking atmosphere of the times. They were lighthearted, flamboyant, even frivolous. Gardens became almost theatrical sets in which to hold lavish parties. Here at Painswick this light-heartedness can be seen in the juxtaposition of serpentine paths with formal vistas, and brightly coloured follies of different architectural styles.”

“But these gardens went out of fashion almost as quickly as they came into fashion. They were seen as being a sign of vulgarity of the owners of the establishment.”

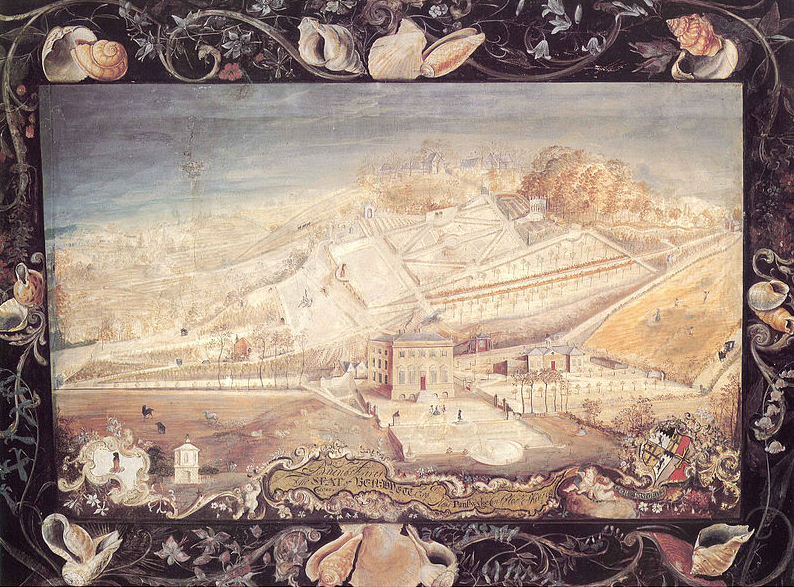

The Painswick Rococo Gardens, as they were in 1748. Painted by Thomas Robins.

Thomas Robins the Elder (1715/16–1770) was an English artist known for his depictions of English country houses and their gardens. His work has particular historical value as he documented many Rococo gardens that have since disappeared. In 1748, Robins painted the Rococo garden at Painswick House that had been created by Benjamin Hyett II.

Plan of the restored Painswick Rococo Gardens

Statue of Pan, by John van Nost ( originally mounted by the Garden’s Plunge Pool ) : now in the private walled garden of Painswick House.

The look-but-don’t-enter-walled-garden of the House

We’re teased by this glimpse of the Exedra

Outside of the Bothy (a gardener’s shed): this is our first view of the Kitchen Garden, which is cradled in a coombe. A coombe is a narrow valley or deep hollow, especially one that’s enclosed on all but one side. Much of the drama of Painswick’s garden derives from its topsy-turvy setting.

A closer look at the Exedra (with a certainly NOT-Rococo-Era-Maze in the background.

The Eagle House has been reconstructed to match the pavilion shown in Thomas Robins’ painting.

Inside the Eagle House

Lower level of The Eagle House. The foundations of this structure are substantial, and had survived over the centuries because blocks of stone were used to retain the steep slope. The surfaces of the lower level are finished with a traditional lime plaster and a red lime wash.

View of the Bowling Green

The long path up to the Red House

The Red House

The Red House, per Painswick’s guidebook:

“This particular building is interesting for its asymmetric façade. Asymmetry was popular in Rococo designs. No third wing was ever intended and the two sections are angled to line up with the approach paths. The façade is finished with lime plaster and a red lime wash.

The building was designed as a dramatic backdrop to the main vista that runs through the garden. The first room is simply furnished with ashlar stone. This would have contrasted dramatically with the inner room which was finished with ornate paneling and mouldings. It still retains the fireplace and the Hyett family Coat of Arms.”

Our view from the front steps of Red House

Inside the Red House. Windows are etched with lines from “The Songs of Solomon.”

Orchard (uphill from the Exedra & Kitchen Garden)

Exedra

The Exedra, per Painswick’s guidebook:

“An Exedra can variously be described as an outside seating area, an apse, or indeed a large recess in a wall. Our Exedra also serves as an

eye-catcher to be seen at the end of a straight vista running through the Kitchen Garden. No trace of it had survived, although archaeologists

found the base of its associated pond, allowing this reconstruction to be placed correctly within the garden. It has been built using traditional methods of timber and lime plaster.”

Anniversary Maze (with Anne Guy helpfully providing human scale). The hedging consists of green and golden privet.

The Maze, per the guidebook:

“1998 was the 250th anniversary of the Robins painting of Painswick Rococo Garden and the garden’s Trustees decided an anniversary

Maze would be a fitting commemoration. Although none was included in the original design, it was felt the light-heartedness of a maze would fit in with the mood of the garden. A site was chosen outside the original perimeter and levelled. Professor Angela Newing, who lived in Painswick, was fascinated with mazes and had always wanted to design one. She developed the idea of incorporating the numbers 2, 5, and 0

into the layout.”

At the Viewpoint: we’re looking over the Painswick Valley, toward Stroud

Doric Seat, by Kitchen Garden. This Seat was originally the porch on the Pigeon House, but was moved to the Kitchen Garden during Victorian times.

Kitchen Garden, with Orchard in background.

Per the guidebook:

“A large kitchen garden is a surprise feature to find right in the middle of a stylized mini landscape, but there is no doubt that one existed here.The re-creation of this part of the garden was helped enormously by the fact that archaeologists found significant evidence of perimeter paths.In today’s kitchen garden, all vegetables are the same types (if not the exact 18th century varieties) as were originally grown.”

Round Pool, in Kitchen Garden

Anne, inspecting the Plunge Pool (above the Bowling Green).

On hot summer days in the 18th century, ONLY gentlemen were allowed to immerse themselves in these cool, spring-fed waters.

A long Beech Walk leads us to the Gothic Alcove. In 1985 the Gothic Alcove was taken down stone by stone and then rebuilt, because its front Wall was close to toppling.

The Pigeon House, “was built at the same time as the main house and was originally open arches. The painting shows it as not being an integral part of the 1740s garden, however it was the location from where Robins based his perspective for the painting. Close examination of the painting will show the artist sitting under a tree near this building.”

Our final peek into the Walled Garden of Painswick House.

![]()

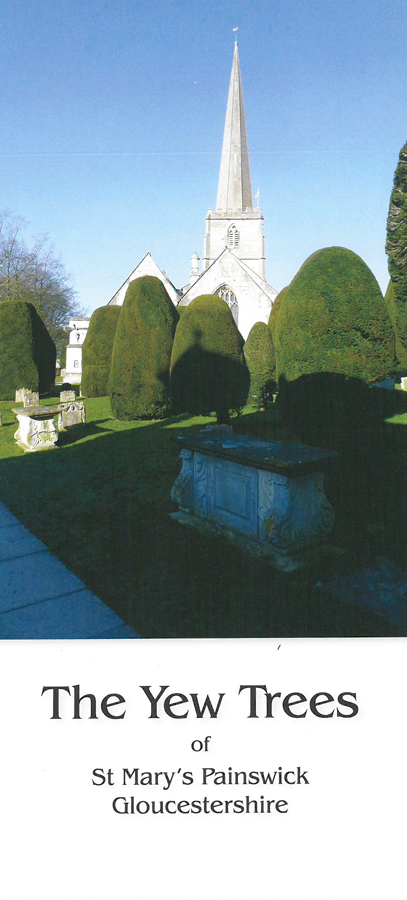

*Painswick St.Mary the Virgin Churchyard

In the Centre of Painswick, on the A46 Road, between Stroud & Cheltenham

www.stmaryspainswick.org.uk

NQ’s Notes: Just down the street from the Rococo Garden, in the Village centre, stop at the Church (begun in 1377), and wander through the churchyard, where 100 ancient, sculpted yew trees present a surreal sight. On a sunny day there, the yews cast long shadows which make the churchyard seem like a de Chirico painting, come to life.

St.Mary’s Churchyard,

Painswick.

Image courtesy of

Trevor Radway.

Per St.Mary’s Church:

“There is a legend about the Yew Trees in Painswick Churchyard.

It states that there are only 99 trees and that the 100th will never grow.

Many of the trees date back to the 18th century.”

“Why 99 Yew Trees? One theory is that the trees thrive over a good source of water. In the past a view has been expressed locally that there are 99 ‘blind’ springs in the Churchyard and the 99 trees grow over them.

What IS known is that an underground stream runs under the path,

which leads from the Town Hall to the east end of the Church.”

“In 2000 the Church planted the 100th tree when every parish in the Diocese of Gloucester was given a yew tree to plant to mark the

New Millennium. This tree thrives to this day.”

“The Yew Trees are trimmed every September because it is late enough in the year to ensure that no noticeable re-growth happens in the same year. The clippings from each of the trees are very poisonous but they

also have medicinal qualities.”

The Yew Trees enjoy longevity due to their unique growth pattern. The branches grow down into the ground to form new stems, which then rise

up around the old central growth as separate but linked trunks. The central part may decay leaving a hollow tree. So the Yew Tree has always

been a symbol of death and re-birth.”

View from the Church Tower. Image courtesy of Peter Llewellyn.

Another view from the Church Tower. Image courtesy of

Trevor Radway.

Here are some of my Churchyard photos, taken on an overcast June afternoon:

![]()

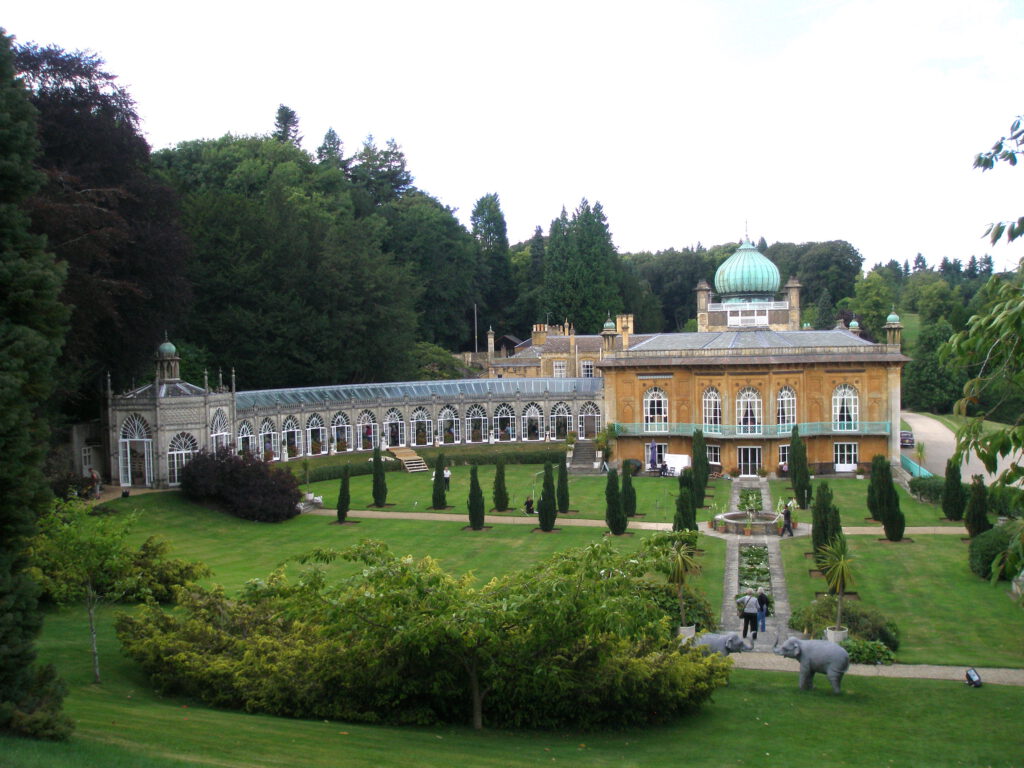

*Sezincote House & Garden

Near Moreton-in-Marsh, GL56 9AW

www.sezincote.co.uk

NQ’s Notes: Sezincote is still a family home…but WHAT a home!

The house’s exterior is a 215-year-old reproduction of a Mogul Indian palace, in the style of the Emperor Akbar ( but you can skip touring the interior…it’s purely classical: aka Greek revival ). Surrounding this architectural confection are Hindu-and-Muslim inspired gardens, collections of rare trees and shrubs, water gardens, and elegantly-decorated hideaways…all cradled in a verdant Cotswold landscape that’s dotted with grazing cattle. Somehow, this utterly bonkers Onion-Domes-in-Albion mix actually works! Strolls through the charming but always surprising gardens, followed by afternoon tea in the exquisite Orangery, have always elated me.

The House & Persian Garden. The house was begun in 1805 for Charles Cockrell, and designed by his brother, architect Samuel Pepys Cockrell, who was assisted by artist Thomas Daniell (who also created many of the garden’s most beautiful, built features). The Paradise, or Persian Garden, is a 20th century addition. Image courtesy of Sezincote Garden

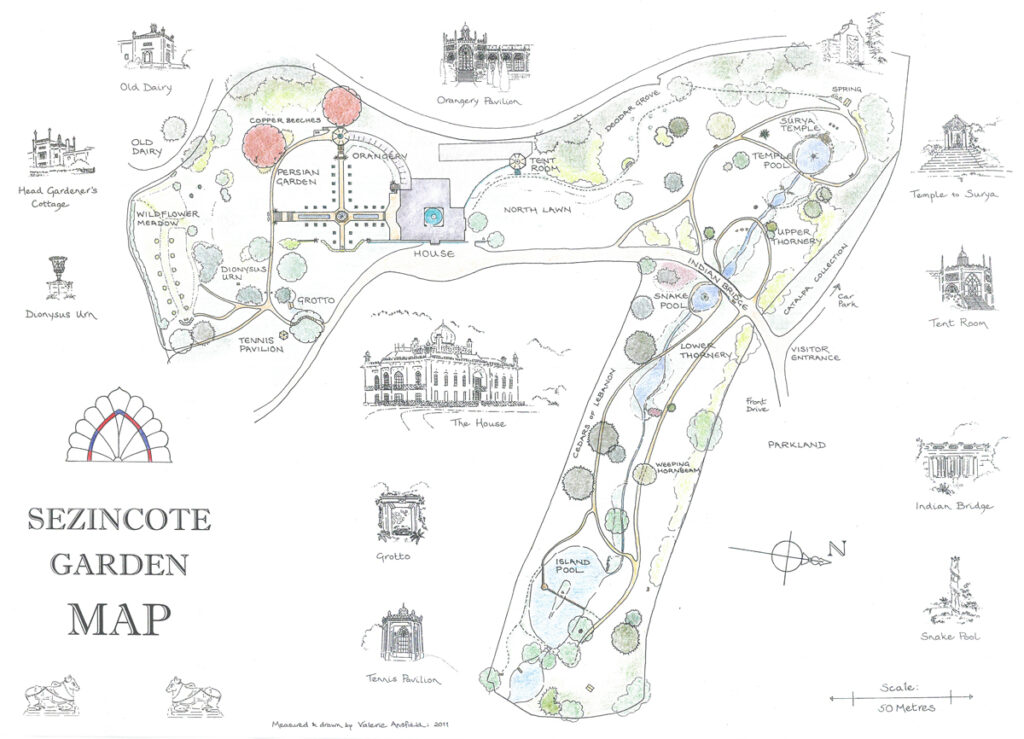

Map of the Gardens at Sezincote

Let’s explore the Gardens….and please don’t be confused by the dramatically different qualities of the light, and varying foliage conditions. These photos were taken on several afternoons, over the course of six years. The owners of Sezincote assume that garden designer Humphrey Repton was initially consulted regarding the overall layout of the Gardens, but Repton wrote that oversight of the project then “devolved” to Charles Cockrell’s architect-brother, S.P.Cockrell.

To enter the Gardens we cross the

Indian Bridge: designed by Thomas Daniell and decorated with bronze images of Brahmin bulls (Nandi, the favorites of Shiva)

View of the Indian Bridge from the Upper Thornery

Our view from the Bridge, looking east, down to the Lower Thornery

Our view from the Bridge, looking west, towards the Upper Thornery

The underpinnings of the Indian Bridge are marvelous, and contain a hidden water garden.

Hidden under the Bridge is stone bench: a perch for viewing the Snake Pool

Below the Bridge: a stunning series of stepping stones. Of all the nooks and crannies in these Gardens, this spot is to me the most magical: the brook echoing and splashing, rays of light reflecting off of stones and the water…sublime.

The Upper Thornery:

to the north of the House, and west of the Indian Bridge

The Upper Thornery. Except for the garden’s many venerable trees, most of the plantings that we see today were introduced after WWII by Lady Kleinwort, with the assistance of Graham Thomas. Sir Cyril and Lady Kleinwort purchased the estate in 1944 and began a complete restoration of the house and gardens. Now their grandson

Edward Peake and his wife Camilla live there.

The Temple Pool. My first visit to these gardens

was in August of 2013, with dear friends Anne and David Guy and Janet Hardwick. Here, Janet and Anne contemplate Surya, the sun god.

The Temple Pool, during my most recent visit to Sezincote, in July of 2018.

The Surya Temple is the focal point at the Temple Pool, and was designed by Thomas Daniell.

The Snake Pool is directly below the east side of the Bridge.

A gushing stream forms the spine of the Lower Thornery

Lush plantings alongside the stream in the Lower Thornery

Streamside, in the Lower Thornery

The Lower Thornery’s stream feeds the Island Pool

The Island Pool

Wooden bridges lead to the Pool’s Island

Cattle graze in pastureland near the Island Pool

We’ve left the water gardens that are situated in the ravine of the Lower and Upper Thornerys, and are now approaching the House. The first structure we see is this Tent Room, on the North lawn.

Skipping up green metal steps and into the Tent Room, we find this delightful ceiling!

Detail of the exterior of the south side of the House. Photo courtesy of Anne Guy

Detail of the exterior of the south side of the House.

Photo courtesy of Anne Guy

Fence-shadows along the south side of the House

My favorite view of the House, as seen from a grove of copper beeches

The Orangerie

Decorative detail, in the Orangerie

Tea-and-Cake-Time, in the Orangerie

View of the Orangerie & the House, from the Persian Garden

The Persian Garden’s steps, leading up to the Wildflower Meadow and the Old Dairy

The Persian Garden’s Canals, added in 1965 by Sir Cyril & Lady Kleinwort, were modelled on a Mogul design. Irish yews flank the waterways.

Even the Old Dairy is designed in an Exotic Style

A bit of classical décor, provided by the Dionysus Urn

The Tennis Pavilion

Our view of pastureland, as we stood on the south lawn of the House.

…and the Shadows of we who were enjoying that same view,

on a perfect August afternoon, in 2013:

LR: Anne Guy, David Guy, Nan Quick, Janet Hardwick.

![]()

*Upton Wold Garden

Moreton-in-Marsh GL569TR

www.uptonwold.co.uk

NQ’s Notes: This private garden and arboretum, which lies at the center of a working agricultural estate, has been created over the past 47 years. It began with the help of landscape artists Hal Moggridge & Brenda Colvin, but has been greatly expanded and refined by the owners of the estate, who are horticulturalists and collectors of trees…particularly of walnuts (they’ve established one of England’s National Collections of Juglans, with nearly 170 cultivars). Upton Wold’s gardens—simultaneously refined and unpretentious, lucid and mysterious—

masterfully combine views ( distant, and close ), movement routes ( instinctual, rather than authoritative ), deep shadow and blazing light, and structure (living, and of stone). On July 4, 2018, as I explored the grounds, the serenity and beauty of this Creation stunned me.

Only later, after I analyzed what I’d seen, did I begin to understand the finely woven brilliance of the garden’s seemingly-organic architecture.

Visitors are welcome, but all viewings must be by appointment only.

The Labyrinth, designed by Hal Moggridge, was completed in 2013, and is situated beyond the Walnut Orchard…where it’s surrounded by grazing cattle and pastureland. This striking landform, embellished with standing stones that remind me of Cornwall’s ancient granite circles, was created to be a destination beyond the Juglans arboretum. During peaceful walks along the Labyrinth’s path, one can contemplate the nearby site of the medieval village of Upton, which was deserted after the Black Death.

Customarily, I provide Maps, and then present photos of the gardens in these DIARIES in a sequence which matches that of my wanderings through those spaces. But to illustrate Upton Wold, I’m going to organize my pictures thematically.

On the hot, breezy July morning of my visit to Upton Wold, I met the Gentleman of the establishment in his walnut orchard, where he and his

gardeners were wielding chainsaws and loppers as they did some serious tree-pruning. I asked him when his interest—or perhaps obsession—with walnut trees had begun, and he told the charming tale of how his love for these trees had started, when he was just a boy. If you

visit the gardens, and happen to find the owner in a voluble mood, perhaps he’ll share his story with you! Following our chat, he was itching to get back to his tree-shaping, and I was eager to discover the gardens. As we parted, he declared that he’d intentionally never drawn a grounds-map for visitors, chuckled, and then declared “You’re a garden writer. See if you can find everything that’s here; I want to see how good you are!”

And I did discover it all, but not because of my garden-exploring expertise. Instead, I found that by simply opening myself to the sensory clues around me, the garden gently told me where to go next. When passing through shadowy areas, patches of sunlight ahead always led me forward. Curving pathways of low-mown turf directed me across broader expanses of grasses or fields. Arching tree limbs created enticing tunnels. Gateways and portals beckoned… almost always visible from a distance. Countless windows carved through what seemed to be endless barriers of precisely-clipped greenery tempted me to find ways around those living walls, and into adjacent garden “rooms.” Sounds of water splashing, of rustling leaves, of breezes sweeping in from the high pasturelands, encouraged me to move along with the wind. And whenever I felt as if I needed a sit-down, I’d turn a corner and find a bench…a resting-spot which seemed to have been put there, just for me.

We’ll take a few more turns around the Labyrinth, and will then wander through the Walnut arboretum. But then—and although I could very well draw you a serviceable Plan of the place—my photos will not reveal the routes I took through the gardens. Instead, these images from that July morning will be organized in groups to illustrate the ways in which seemingly-simple devices of design are repeated throughout the gardens.

I’ll show you bunches of paths, portals, ponds, precisely-clipped greenery, perching-places, and peep-holes. It is this rigorous use of a visual vocabulary—but a vocabulary which is then consistently tweaked to be just a BIT surprising—that lends harmony, and also provides direction, within the intricately-composed spaces of Upton Wold.

So…NO MAP ! If someday you find yourself at Upton Wold, I want you to enjoy those same pleasures of discovery, as I did.

The Labyrinth

The Supervisors of the

Labyrinth

Path leading away from the Labyrinth, towards the Walnut Orchard, & past that, back into the Gardens.

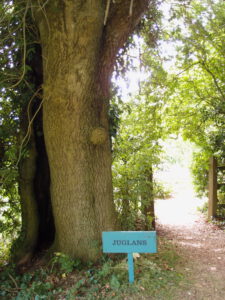

Where the Gardens meet the Walnut Orchard

Always acquiring new cultivars of Walnuts, the owners continue to expand the Orchard. The following 5 photos show walnut trees,

at different stages of maturity.

PATHS:

PORTALS:

PONDS:

PRECISELY-CLIPPED GREENERY:

PERCHING-PLACES:

PEEP-HOLES (formally known as CLAIRE-VOIE, which means “let the light through”)

And for our final view of the Gardens at Upton Wold: The Sky above the Rose Garden’s Pergola:

![]()

*Westbury Court Garden

Westbury-on-Severn GL14 1PD

www.nationaltrust.org.uk/westbury-court-garden

NQ’s Notes: This is the only restored, Dutch-Style water garden in England. It’s small, but mesmerizing (and often empty of Visitors).

Laid out in 1696 in the wetlands adjacent to the Severn River, what remains today is but a small portion of the original, which is thought to be have designed by the owner, Maynard Colchester, and subsequently elaborated upon by his son. Pass through the entry gates and be transported into a fragment of a very rare late 17th century formal water garden.

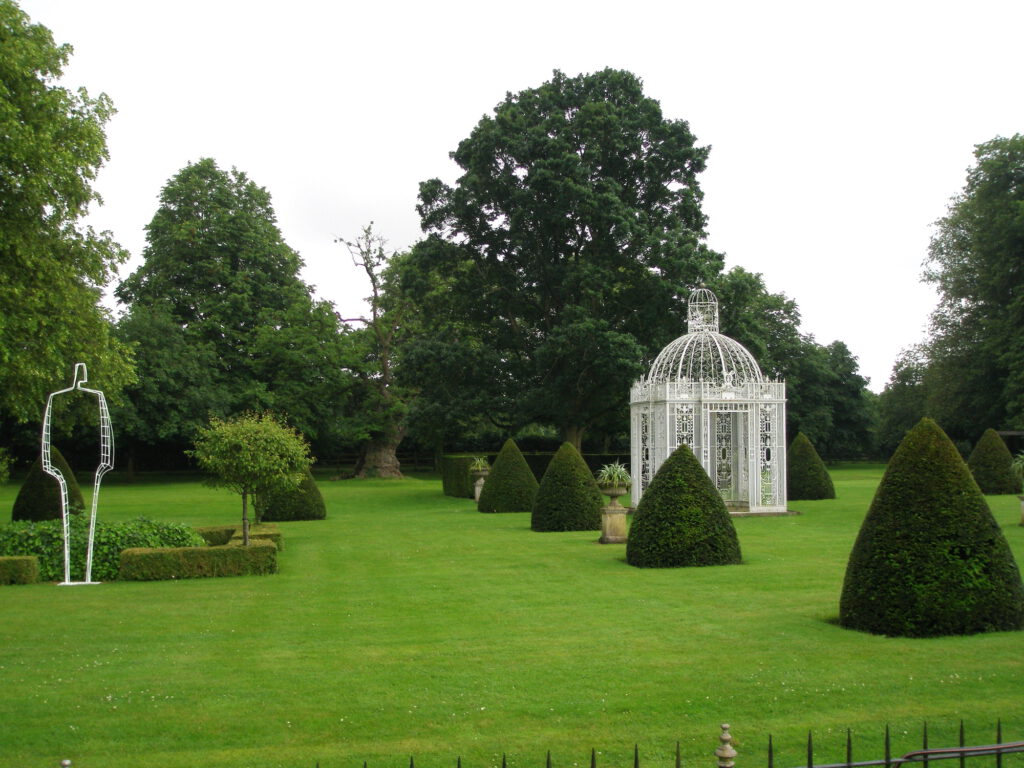

The Tall Pavilion. Built in 1702-3, this garden folly has the style and elongated proportions favored by the

Dutch, in the late 17th century. The structure’s plan is simple, with a loggia on the ground floor, and an elegant, many-windowed, tulipwood- panelled room upstairs. The Pavilion sits at the south end of the Long Canal. Reflected in the 450 foot long Canal, the Tall Pavilion seems to be a MUCH Taller Pavilion. Image courtesy of Westbury Court

In 1796, a Lady Sykes wrote of her visit to Westbury:

“…here we saw a Stone Mansion, with formal old Gardens, long

Fish Ponds, High Walls and Stone Neptunes, but sweetly situated on the banks of the Severn.”

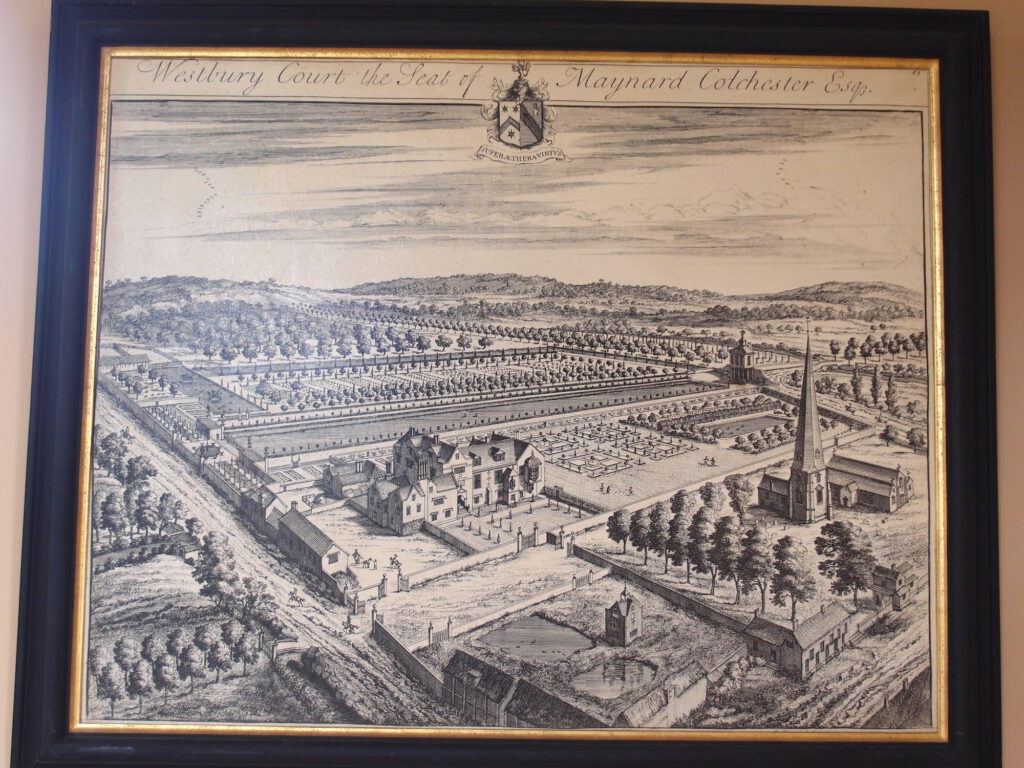

In the Walled Garden’s little Summer House, I found this copy of an engraving (circa 1705) that shows the estate

prior to its zenith, during the life of the original owner,

Maynard Colchester I.

By 1745, Maynard Colchester II, had demolished the Tudor-style mansion shown above, and replaced it with a grand, Palladian-style edifice. Maynard 2nd had previously added a large T-Canal, a Walled Garden and Summer House, along with many statues of heraldic beasts.

The very existence of this snippet of once-grand gardens is a miracle. The Colchester family decamped from Westbury in the late 18th century, and the bones of the garden quietly crumbled until 1960, when [per the National Trust]:

“…it was sold to a property developer, who planned to fill in the canals and bury the garden under bungalows. Fortunately, the local council came to the rescue, acquiring the remnants of the garden and handing it over to the National Trust in 1967. Over the next six years, the Trust brought Westbury back to life, in what was the first scholarly garden restoration of its kind.”

But threats to the garden’s existence continue:

“Westbury was rescued from the brink of extinction, but now faces new challenges. With global warming, flooding from the Severn has become

more common, waterlogging the roots of the yew hedges, which are now suffering from the phytophthora virus.”

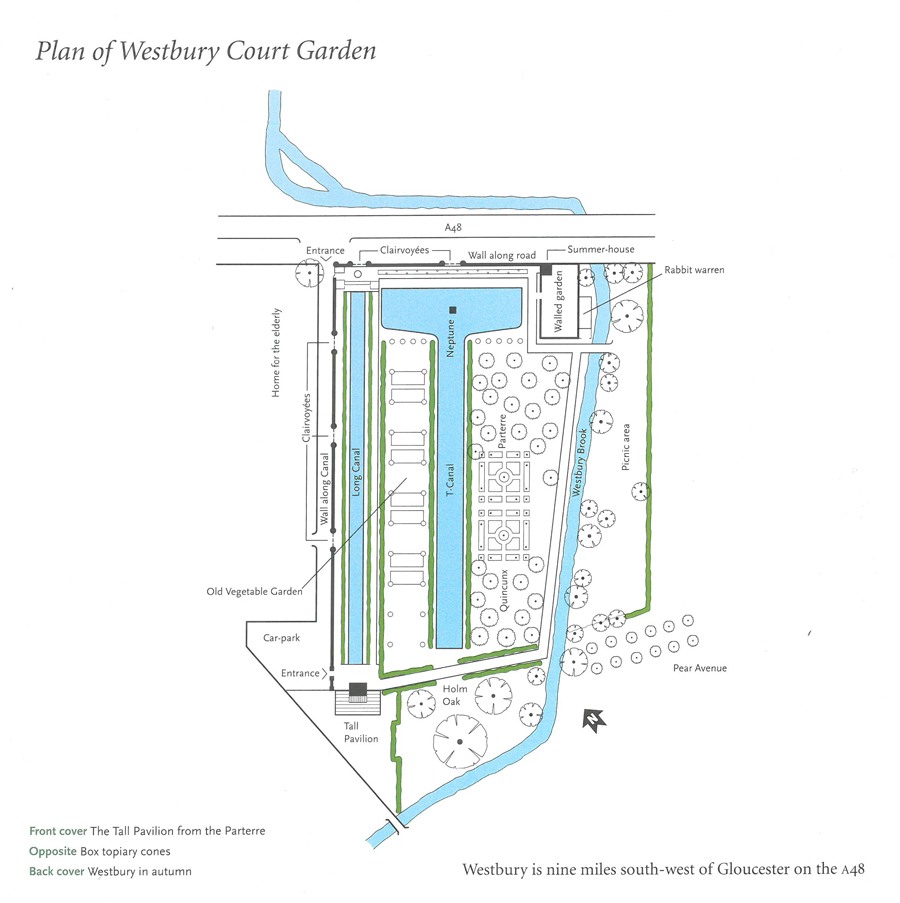

Current Plan of the Gardens at Westbury Court

We’ll take a stroll around the Gardens:

The Tall Pavilion

The Trust’s Guidebook recommends beginning your visit on the Holm Oak Lawn, but upon entering, I headed north, up the path that runs

alongside the Long Canal toward the farthest reaches of the garden. In gardens (and at art shows and in museums), a contrary instinct often propels me to investigate denouements, first. I like to start my tours at the endings, and then inch my way in reverse, towards the entrance: considering the backs of things before I contemplate their faces helps to keep my mind open and my eyes sharp.

The northwest corner of the Gardens

Turning around, I stop to admire the path I’d just taken

This circular pool sits at the north end of the Long Canal.

Straight ahead we see the Summer House. The four towering squares of clipped yew stand in for the little pavilions which originally decorated this area.

Va Va VOOM! Now THIS is a VIEW

The Long Canal was the first element made in Maynard Colchester I’s new garden. Currently, the Garden ends just to the north of the circular pool, at the brick wall that hides the A48 Roadway. Per the Trust:

“Originally, the vista was even longer, taking in an avenue of trees planted on the far side of the [then much smaller] road, which would have been visible through the clairvoyee, or open wrought-iron screen, at the far end of the canal.”

Another view from the terrace at the circular pool. Behind the

long yew hedge is the Old Vegetable Garden.

We’re looking at a portion of the T-Canal, with the Veggie gardens to the rear.

Neptune, standing astride a dolphin: lording it over the T-Canal. This statue was already venerable when the gardens were still new…thought to be made in the early 17th century. Maynard 2nd added this major water feature in the 1720s. Such aquatic displays were practical, as well as ornamental: fish to feed

the occupants of the Estate swam in these large expanses.

At the far end of this Canal stands the 400+ year-old Holm Oak.

We’re approaching the Summer House, which anchors a corner of the Walled Garden.

Interior of Summer House

Entrance to the Walled Garden

The Walled Garden, with view of the T-Canal, and the steeple of the Church of Mary, Peter and Paul

We exit the Walled Garden and head south, towards the Orchard, the Double-Quincunx, and the Parterre.

Grass paths, mown through a little Orchard

Just beyond those fruit trees, we find the Quincunx, one of two that flank the Parterre. A Quincunx is a garden formation with five clipped trees, arranged in a square, with a tree at each corner and one in the center. The precision of the trees’ forms, combined with the looseness of the tall grasses around the paths here, is delightful.

A closer look at the Quincunx (with the Parterre behind it).

The Parterre, and the Tall Pavilion, as seen from Quincunx

The Parterre

The Parterre, and the other Quincunx, with the floodplains of the River Severn in the background.

Westbury Brook runs along the south and east sides of the Garden. During flood season, these fields are entirely submerged, and the Gardens are imperiled.

The Holm Oak (Quercus ilex) !!! This old fella, planted around 1600, predates the Garden and is one of the oldest Holm Oaks in England.

The Holm Oak’s Bark. The young lady mowing the lawn around the Oak turned off her engine, and took time to talk with me

about her love for this STILL VERY HEALTHY tree, for the Gardens, and of the challenges she and her volunteers face, as flooding becomes more frequent. Guidebooks are good sources of information, but the comments of such dedicated humans are even better.

I headed back towards the Tall Pavilion, passing a just-chopped hedge…

… then nipped into the extensive, Old Vegetable Garden.

The upper floor of the Tall Pavilion

The Tall Pavilion

Even in its current, much-diminished state, Westbury Court is impressive. But to give you an inkling of just what a huge horticultural endeavor it once was, here’s the National Trust’s description of what Maynard Colchester did, once his Long Canal, and framework of walls had been laid out:

“Colchester ordered 500 hollies and yew bushes in the spring of 1698. Then next season another 1000 yews and 1000 3-year-old hollies arrived.

2500 more yews followed during the next five years as Westbury’s immaculate pattern of hedges, topiaries and parterres took shape. The accounts also record purchases of hundreds of spring bulbs—tulips, iris, crocuses, and hyacinths—together with shrubs, fruit trees and vegetables, including no fewer than 2000 asparagus plants. Westbury at its height must have been a delight to both the eye and the taste buds.”

Gardens such as Westbury Court, whose vestiges have been rescued from oblivion, are valuable as living, photosynthesizing, historical sites.

The 90 minutes I spent there in 2017, on a warm June morning, were a sublime form of time-travel.

My view, from the upper floor of the Tall Pavilion.

![]()

GARDENS IN BUCKINGHAMSHIRE:

(not officially in the Cotswolds, but nearby, & all enormously worth visiting)

*Chenies Manor House & Garden

Chenies, Rickmansworth WD3 6ER

www.cheniesmanorhouse.co.uk

NQ’s Notes: Chenies Manor, at the center of a tiny village (population approximately 170), is a fine, brick Tudor mansion that’s built atop a 13th century undercroft. Surrounding this home of the Russell family are a series of gardens that function as outdoor rooms. In these compact but dazzling spaces, where most of the gardens we see today were established in the late 1950s by Mrs. MacLeod Matthews, the current owners have combined voluptuous plantings with a well-curated selection of contemporary art. Their highly theatrical approach to garden decoration, achieved via exciting juxtapositions of plant material and sculptural elements, produces unforgettable and occasionally surrealistic effects. I visited Chenies’ gardens on a stormy afternoon in June of 2016, when the colors of the rain-soaked flowers and greenery were incandescent. The dramatic weather that day matched the garden’s vivid character.

The Sunken Garden on a Sunny Day. Image courtesy of Chenies Manor.

In their Guidebook to the gardens, the Russells explain:

“The gardens of Chenies Manor have always been closely connected with the house — intended to be viewed from various rooms, and to furnish inward vistas of the ornamental buildings. They are not therefore formed as ‘landscape,’ but as an intimate whole with the house. They represent the old style that had prevailed before the Dutch and French designers, followed by the ‘landscapers,’ implanted their ideas in the late 17th and 18th centuries.”

Long-time Readers may recall my photo-tour of the sunken gardens at Hampton Court Palace, which were created to please the irascible

King Henry VIII ( December 2012: “The Great Canopy of London’s Skies…Garden-Strolling at Hampton Court Palace.”).

The presence of Henry VIII, who visited Chenies Manor, is still felt there, in the house itself, and also in the gardens on the west side of the Manor.

The residents tell us: “An archway leads west…onto a small grass terrace overlooking a sunken garden. This is a close model of the early Tudor

‘Privy Garden’ at Hampton Court and was perhaps laid out in compliment to King Henry VIII. “

During Henry’s reign, John Russell, the master of the Chenies Manor (and the ancestor of the present-day Russells who live there), “several times received Henry VIII and his Court at the Manor, particularly in 1534 (with Ann Boleyn and the baby Elizabeth), and in 1541. On the latter visit he was accompanied by Catherine Howard, his fifth Queen, who was carrying on an affair with one of the King’s attendants, Thomas Culpepper. This culminated in her adultery, Chenies being one of the houses where it took place. The King was suffering at the time from an ulcerated leg; the sepulchral footsteps of a lame man are occasionally heard on the staircase and in the gallery approaching the wing in which Catherine met with Thomas Culpepper,

and are said to be those of the King.”