The garden at Charleston’s Heyward-Washington House (circa1771) is one of the loveliest refuges in the Historic District, the area that’s also known as S.O.B. (more about that later). All plants in the Garden, which is maintained by the Garden Club of Charleston, were introduced to the Low Country no later than 1791. Visitors will see camellia, tea olive, boxwood, anemones, roses, herbs and more.

For Northern New Englanders, March always seems the cruelest month. Winter–which begins in November–persists…and sometimes mightily. As gray days continued, and new snow piled upon old, I decided that a Southward trip was needed for mental and physical health, and so devised a two-week itinerary which would carry me into Springtime.

Here’s incentive to leave! On March 8th, a fresh foot of snow blanketed my New Hampshire back yard, which made my March 9th departure to Points South seem even more sensible.

March 9, 2013. I had cast my eyes toward warmer climes and realized that although I’d long been interested in Charleston, South Carolina, I’d never traveled there. The highlight of this trip would thus be to remedy that omission. But, to avoid the Purgatory that flying has become, I decided the destinations on my little journey should be joined together by a series of train rides. I began to think of each of my planned stops—Manhattan; and Charleston; and Palm Beach, FL; and Washington, DC—as pearls upon a string. Amtrak could never be considered a Pearl, but a strong and serviceable String? Yes….a String… which would guarantee me hours of quiet and rest between busy times in each of those four cities. And so I set out on the first of my five train rides; this one the very shortest, from Boston to New York City. Each time I emerge from a train at Penn Station, I marvel that such a great City as New York should have such a squalid terminal, one that’s often likened to a rabbits’ warren (or, more accurately, a rats’ nest).

Trust me: the platforms at Penn Station, and then the endless, upstairs corridors, are much grimier than they look in this photo.

My reason for this day and a half pause in NYC was simple: I needed a Serious Art Fix, and planned to spend all of Sunday at the MET. That Saturday evening I bedded down at the Kimpton-managed 70 Park Avenue Hotel….

My room at the 70 Park Avenue Hotel. When I arrived, I was welcomed with with gifts: a bottle of very good Cabernet Savignon, slippers, and a fine assortment of cheeses. I’ve always been a FAN of Kimpton Hotels, but these unexpected goodies clinched my devotion….especially since the Hotel had no idea that I’m a travel writer.

….and, on Sunday morning…

The early-Sunday-morning view from my hotel room. As Readers of my past articles have discovered, I’m inspired by hotel- room views.

… after a fortifying room service breakfast….

…I set out along chilly, empty sidewalks on my 2.61 mile trek to the Metropolitan Museum of Art. I shall never attempt to write seriously about New York: 65 years ago, the essence of the City (which persists, despite Manhattan’s never-ending transformations) was described as well as it will ever be (see E.B.White’s timeless essay HERE IS NEW YORK), and so this visit was mainly for private edification. BUT…I cannot resist making a suggestion (or two). Dawdling over lunch in the Museum’s Petrie Court Café –which offers OK food but perfectly wonderful views of Central Park– and then wandering through the spectacular New American Wing (which was opened in 2012) is one of the most pleasant ways to noodle around on a New-York- Sunday that I can imagine. Literally tens of thousands of pieces of American art and craft are displayed in the New American Wing. Here: a tiny fraction of that bounty. One enters the New American Wing through The Charles Engelhard Court, which the MET’s website describes: “This vast, light-filled space presents the Museum’s unsurpassed collection of American monumental sculpture, architectural elements & stained glass. It is the grand vestibule to the American Wing, which houses period rooms & galleries for American decorative arts, paintings and sculpture.”

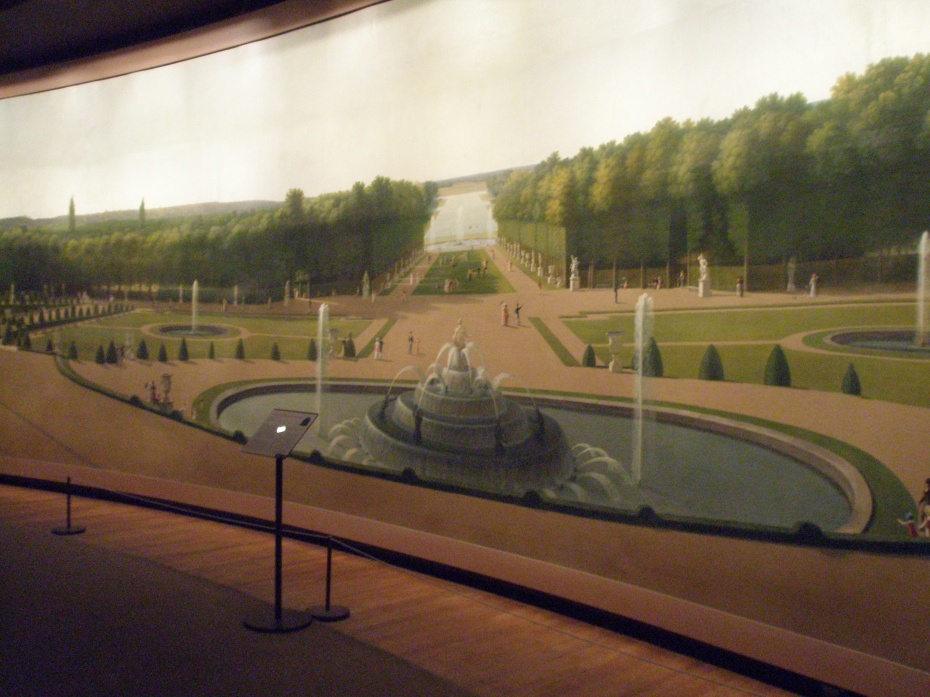

One of the Major Curiosities of the New American Wing is the Vanderlyn Panorama, described in the MET’s exhibit notes as a “Panoramic View of the Palace & Gardens at Versailles (painted 1818-19), by John Vanderlyn (1775—1852). This is a rare survivor of a form of American public art and entertainment that flourished in the 19th century. Panoramas were displayed within the darkened interior of a cylindrical building and then illuminated with concealed skylights, offering the illusion of an actual landscape.” As someone who travels the World in search of honest-to-goodness-garden-views, I was thrilled that such large-scale attempts to replicate being in famous gardens were once considered popular entertainment!

Another treasure on the first floor is an entire Frank Lloyd Wright room, “originally the living room in the Prairie-style lake house in Wayzata, MN, created for Mr. and Mrs. Francis W. Little.” Of course, visiting an actual Wright building, one which can be walked through instead of being peered at from behind a velvet rope is always better, but even this truncated bit of Wright is worth a look.

Working my way upstairs to the Painting Galleries, I stumbled upon the Henry R. Luce Center for Study of American Art, which is literally a library, where countless numbers of objects are stacked behind glass (each thoroughly described via the Center’s database): furniture, pottery, paintings, tableware, clocks, curios….centuries of the Best and/or Oddest American Clap-Trap!

But… before we chug along down to Charleston, which is after all the main topic of this article (no…I hadn’t forgotten) here are some of the most iconic of the American Wing’s paintings:

On Monday, March 11th, I arose at an Unspeakable Hour to catch the Palmetto, AMTRAK’s 6:15AM train to Charleston, South Carolina. My customary approach to long-haul train rides (arrival in Charleston wouldn’t happen until 7:15PM) is to reserve a bedroom, but the Palmetto offers only upright seating, and so, hoping that my 6 miles of walking on Sunday had made me extra-limber, I settled into my Business Class chair and tried to achieve the Zen-like state which the day’s long ride would demand. But train travel lends itself to daydreaming… sinking into a mood where time becomes meaningless wasn’t difficult; I’ve been practicing such surrender since childhood. When I was girl, my parents, oblivious to the perils which might threaten an unchaperoned eight-year-old, began to regularly deposit me onto trains which ran from Massachusetts to Trenton, New Jersey (most famous then for their bridge which declares “Trenton Makes The World Takes,” and more famous now as the setting for Janet Evanovich’s Stephanie Plum mysteries). My beloved Grandmother Nellie Buck Quick and my taciturn Grandfather Clifford Daniel Quick would anxiously wait for me on the platform at Trenton Station, and would then spirit me away to the Happiness-That-Was-Their-Home at 24 Haslet Avenue, in Princeton, New Jersey. As a Tiny-Independent-Traveler, I learned to be calmly and thoroughly aware of my surroundings, and thus always arrived at my destinations, unharmed. Still—all these decades later—when I ride a train along the North East Corridor, and gaze through the windows at the weirdly magnificent industrial wastelands that surround the tracks, past and present intermingle and I wonder if the same rusted car frames that were piled trackside when I first began pressing my nose against the glass are the same wrecks that I see now. And, while wondering at the constancy of the blurred landscapes which are zipping along outside, I lose all awareness of my age as memories of years and years of travel over these same rails compress. For me, this particular train route is Time Travel of the sweetest sort. More-or-less on time that evening, and only mildly-stiff-of–limb, I tumbled out of the air conditioned chill of the Palmetto, and into the gentle warmth and humidity of South Carolina.

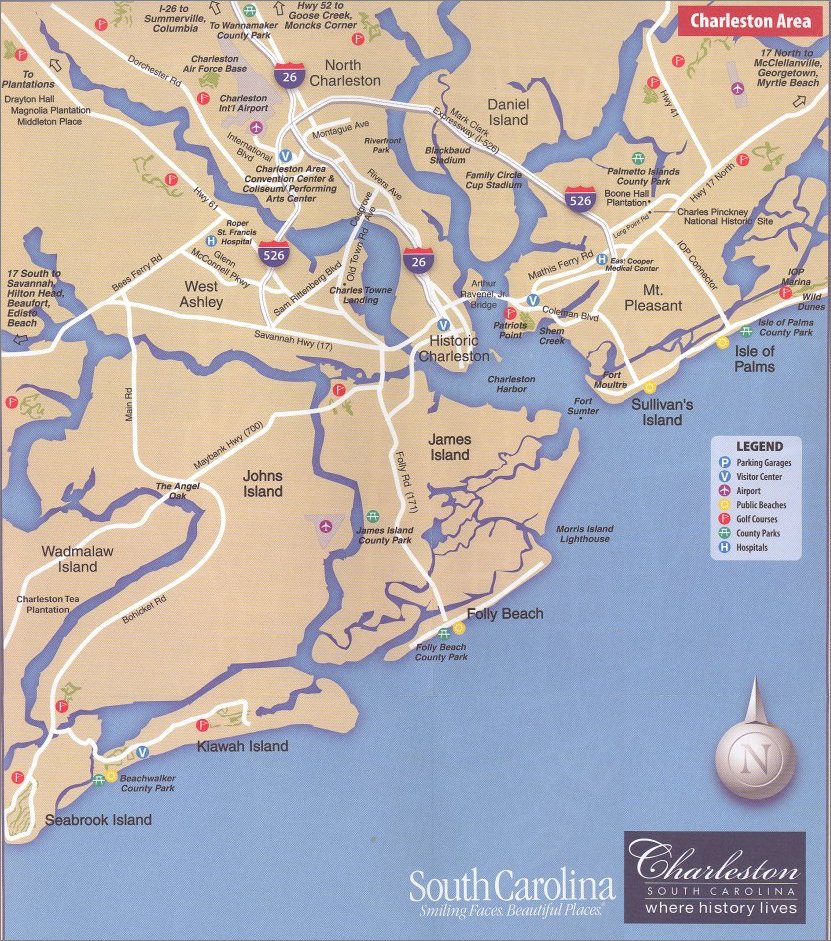

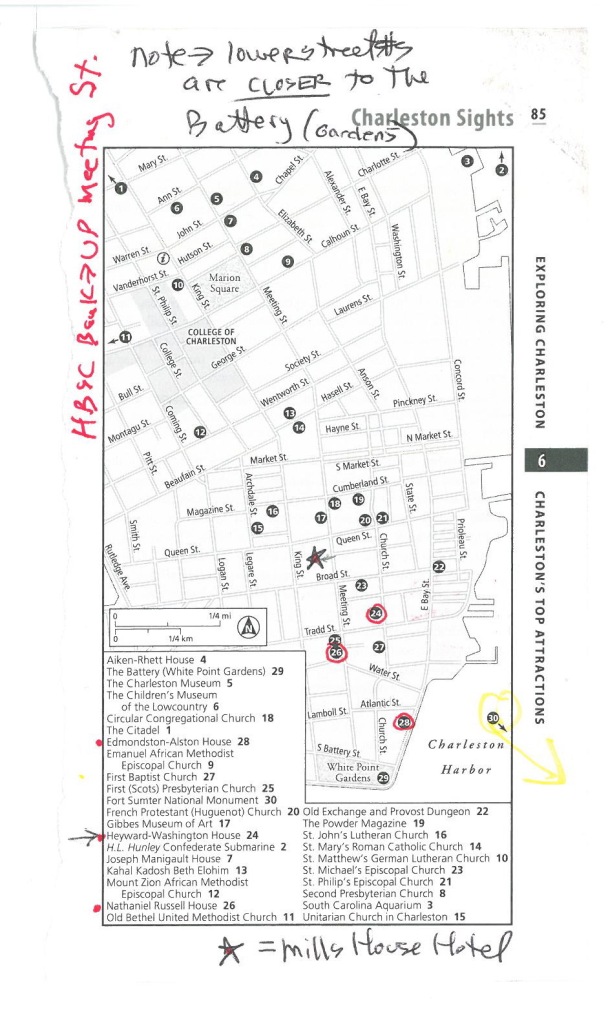

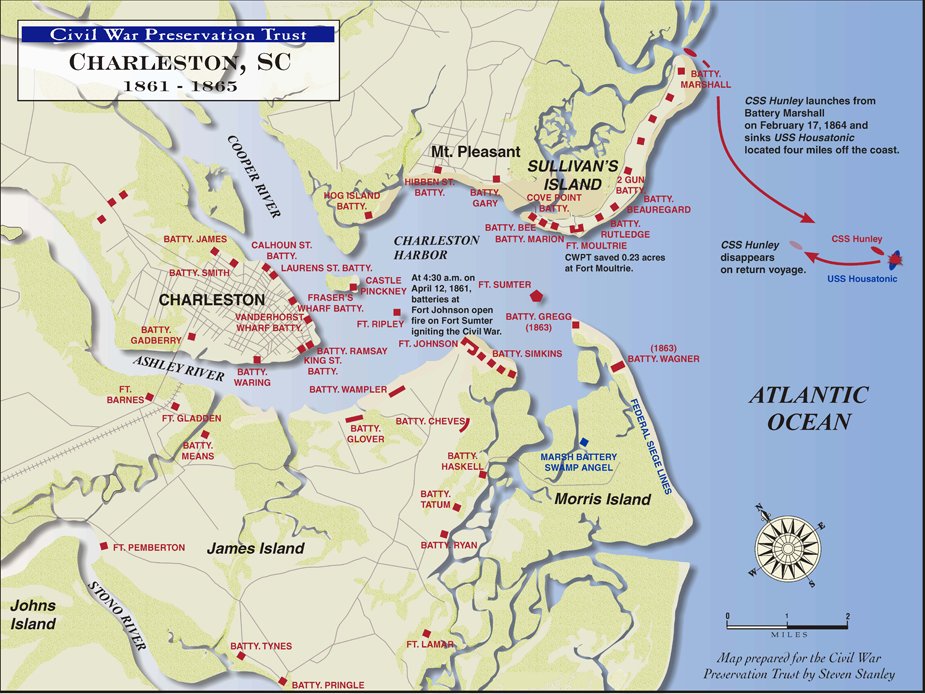

Charleston is on a peninsula, where the Ashley and Cooper Rivers join to form Charleston Harbor, which has always been one of the most important Ports on the Atlantic Seaboard.

Melissa, the extraordinarily helpful Concierge at the Mills House Hotel, where I’d be staying, had arranged for me to be met at the Charleston Station. In the midst of a crowd of about 50 disembarked passengers, I strode through the Station, expecting a man who’d be holding a sign saying “N. Quick,” but I saw no sign. As I scanned one side of the waiting room, I heard a voice: “You must be Miss Quick.” I turned to see the gentle giant who’d addressed me and replied: “And so you must be Greg Patterson, from Journey Transportation! How did you know it was me?” He smiled: “You look PROFESSIONAL; I KNEW it was you.” How pleasant to do business with someone as sharp-eyed and low-keyed as Greg, who, as he drove us during the next several days, let me know that his true moniker is Greg “Big Daddy” Patterson. He’s a hugely-experienced professional driver by day, a stand-up comedian and MC by night (at Charleston’s Oasis Club), and an all-round sterling human being.

Promising to be back bright and early on Wednesday morning for our day-long jaunt to four Low Country plantations, Greg dropped me off at the Mills House Hotel (in the Historic District–115 Meeting Street) where I toppled directly into bed, and then into a deep sleep.

A seagull’s view of the Arthur Ravenel Jr. Bridge and the Cooper River, with Historic Charleston in the foreground.

View from my hotel room down over Queen Street, where I would soon discover Fried-Green-Tomato-Nirvana at Poogan’s Porch Restaurant.

Tuesday, March 12th. SO! I’d finally arrived in Charleston: a place that seems always to have been in the Cross-Hairs…of History, and of Mother Nature. PIRATES. SLAVERY. WARS (Revolutionary, and Civil). FORTUNES MADE. FORTUNES LOST. FIRES. CYCLONES. FLOODS. EARTHQUAKE. FABULOUS ARCHITECTURE (much of it constructed for their owners by supremely talented slaves, and then periodically damaged by most of the other items on the above list). GARDENS. PALMETTOS (as Greg immediately corrected me, when I incorrectly referred to Charleston’s beloved trees as PALMS). &….FOOD, GLORIOUS FOOD! I focused my thoughts with a reconnoiter through the immediate neighborhood, and looked forward to the mid-day arrival of my friend Donn Brous , who was driving in from her home in Northern Georgia.

Aerial View of Historic Charleston, with the brown steeple of St. Philip’s Church fore-and-center. This steeple was once used as a harbor channel light. The Mills House Hotel is the square pink building, half way up at the farthest right edge of this photo. Directly adjacent to the Mills House Hotel is the white, columned portico of Hibernian Hall.

Here, my first glimpses of Charleston on that rainy morning, as I wandered South of Broad Street, in the direction of White Point Garden.

Garbage Collection Day. Yes, even in the fairy-tale land of Historic Charleston, blue trash bins stake their claim to the sidewalks.

In Jonathan H.Poston’s definitive THE BUILDINGS OF CHARLESTON: A GUIDE TO THE CITY’S ARCHITECTURE, Poston describes the Charleston Single House as “the urban house form most closely associated with the historic fabric of Charleston from the mid-eighteenth century. The single house was a creative response to the increasing scarcity of space in the city and was designed to mitigate the unpleasantness of hot, humid summers. With its narrow side directly on the street, the rectangular house with two rooms in each story grew tall to raise the main entertaining room to the level of the prevailing breeze which passed through a side piazza. As a free-standing house communicating more with a side garden than with the street the single house offered a masterful but still vernacular solution to the residential problems of achieving comfort, privacy and propriety.”

An array of Candy-Colored, Single-Wide Houses…these 3 unusual in their lack of side gardens and porches.

Calhoun Mansion, 16 Meeting Street. Constructed circa 1876, with 24,000 sq.ft. of living space, for George Walton Williams. With 25 rooms, this is the largest single-family residence in the city, and is now open as a Museum.

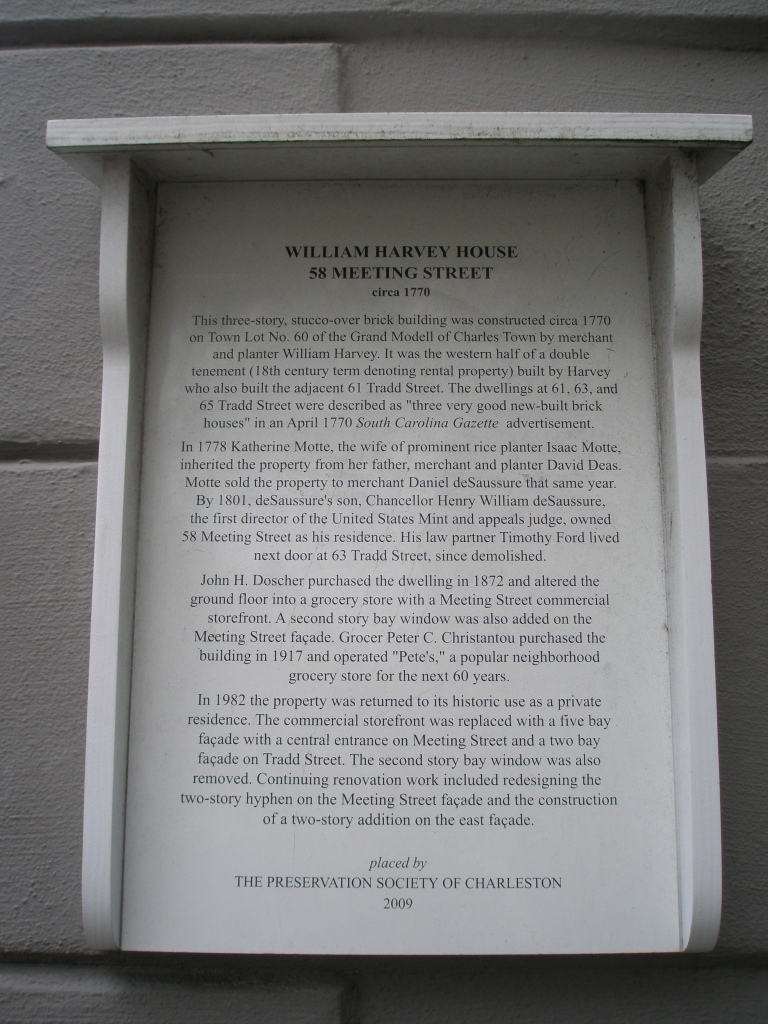

The Branford-Horry House, 59 Meeting Street at Tradd Street. This was built on the Double-Pile Plan in 1750, and the portico which covers the Meeting Street sidewalk was added in 1830.

Stepping Stone at the front entry of the Branford-Horry House. This is what ladies used to ascend to their carriages.

First Scots Presbyterian Church, directly across Tradd Street from the Branford-Horry House. The Church was constructed in 1814, and renovated in 1887.

Peeking (but always respectfully) through ironwork grilles or over fences into the private gardens of the Historic District is a time-honored tradition, and is made even more fun if one knows that such borrowed vistas are spied through what are called CLAIRE-VOIEs. Here…my Claire-Voie glimpses:

I realized that this visit must necessarily be the first of many. During these three days in Charleston, only a mere scratching upon the surface of the City’s Treasures would be possible. In daylight, the Mills House Hotel had revealed herself to be quite the Grande Dame.

I realized that this visit must necessarily be the first of many. During these three days in Charleston, only a mere scratching upon the surface of the City’s Treasures would be possible. In daylight, the Mills House Hotel had revealed herself to be quite the Grande Dame.

Meeting Street, looking inland toward the Very Pink Mills House Hotel, which is just beyond the columns of Hibernian Hall.

Entrance to the Barbadoes Room Restaurant at the Mills House Hotel, where I enjoyed 3 very fine breakfasts.

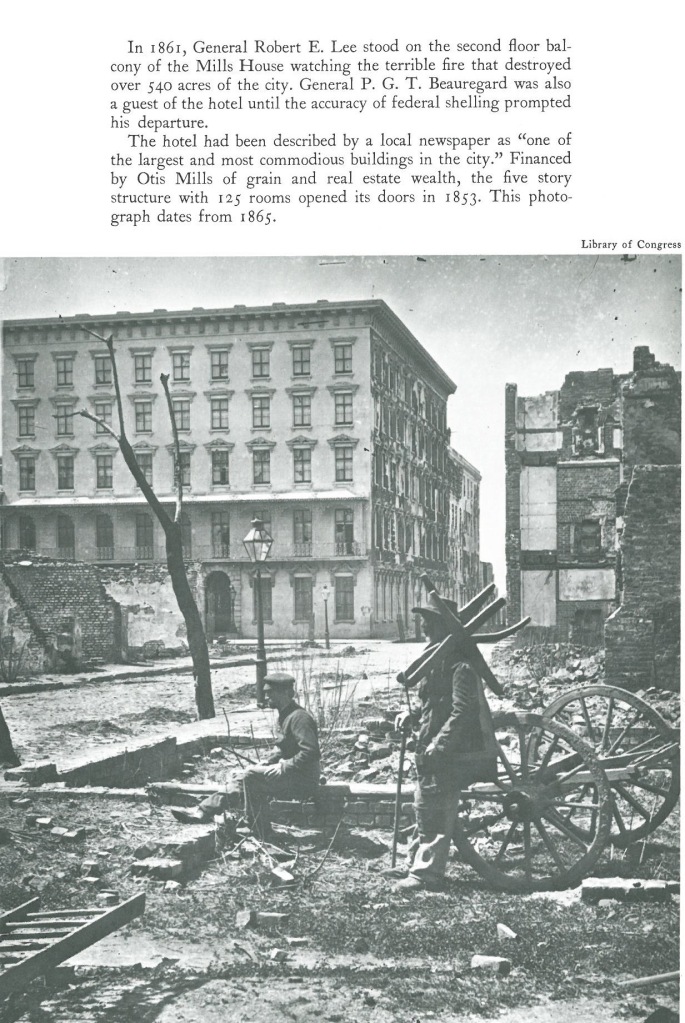

But this Grande Dame, like all of Charleston, has seen harder days…

The Mills House at the end of the Civil War. This image, courtesy of CHARLESTON COME HELL OR HIGH WATER, by Whitelaw & Levkoff.

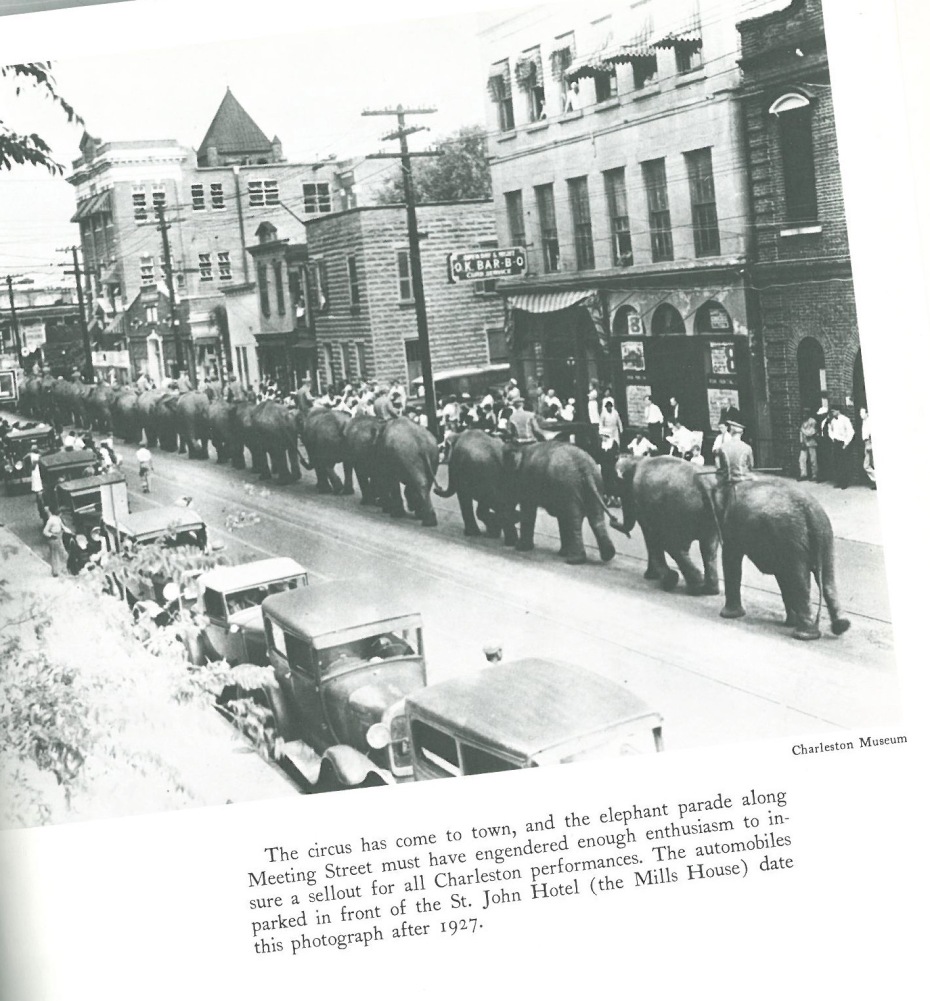

…as well as more comical ones.

I’m sorry that I wasn’t able to see an elephant parade from my hotel room!

This image, courtesy of CHARLESTON COME HELL OR HIGH WATER by

Whitelaw & Levkoff.

Which brings me to a fundamental characteristic; one shared by of all of the homegrown-Charlestonians who I met during my visit. I very quickly understood that the veil which separates Past and Present in Charleston is often quite thin. Having entered a similarly time-fluid frame of mind via my train-musings about memory, I thus was perfectly primed for my immersion into this City where history seems still to be breathing. Charleston is a world in which the distances between Then and Now are not absolute. The City’s natives have a collective memory of Charleston’s glories and disasters which is passed from generation to generation. This provides hugely entertaining and vivid narratives for any visitors who are willing to listen. Of the half-dozen guides who Donn and I encountered during the three days that we spent in South Carolina, none was more informative than Michael Trouche (a seventh-generation Charlestonian whose French ancestors immigrated to the city in the 18th century; host for two decades of the CAROLINA CAMERA television series; historian and author), who leads 2-hour walks through the heart of the City. For anyone with the slightest interest in Charleston, Michael’s book CHARLESTON, YESTERDAY & TODAY is a wonderful starting point. And for any visitor, Michael’s Charleston Footprints tours (which are a bargain at $20.00….I felt I should have paid him at least 4 times that, so good was his presentation) are essential.

Michael demonstrates proper use of a Joggling Board, in the garden of the Nathaniel Russell House (which we’ll visit at greater length…in a bit).

Michael explained the origin of the Joggling Board, Charleston’s most iconic piece of outdoor furniture. Charles Towne’s original settlers were English, French, Irish, German and Scottish. In the early 1800s, a Scottish resident who suffered from rheumatism complained to her relatives in the Old Country about her aches, and her helpful Scottish relations responded by sending her a peculiar bench, made of a long and pliable board, and supported at each end by two rocking-chairs. The theory? If the achy-lady sat on the middle point of the board and bounced gently, that exercise might soothe her pains. I’m not sure that this early version of an exercise-machine cured her ailments, but Joggling Boards soon charmed all who bounced upon them, and became Charleston’s must-have garden ornament… one which is always painted in the city’s signature color, that almost-black Charleston Green. But let’s back up just a moment to my Charleston-Calamities-Check-List, for a lightning-fast overview of just how eventful life in this seemingly-quiet city has always been. (If you’re super-serious about your Charleston history, read Walter J.Fraser Jr.’s CHARLESTON! CHARLESTON! THE HISTORY OF SOUTHERN CITY…a book that demands at least a month’s time of close study). PIRATES. Yes indeed…and the most infamous of the bunch was the English scoundrel Edward Teach (1680—1718), better known as Blackbeard. Teach’s worst misbehavior toward Charleston was his 1718 blockade of the Port, during which all ships docking, or setting sail, were stopped and plundered. But Charles Towne (as it was known until 1783), which was begun as a British settlement in 1663, had always been the object of attack, and not just by pirates. In its early days, the city was raided by understandably disgruntled Native Americans. And the navies of France and Spain, who disputed England’s foothold in the Province of Carolina, periodically did battle with the seacoast town.

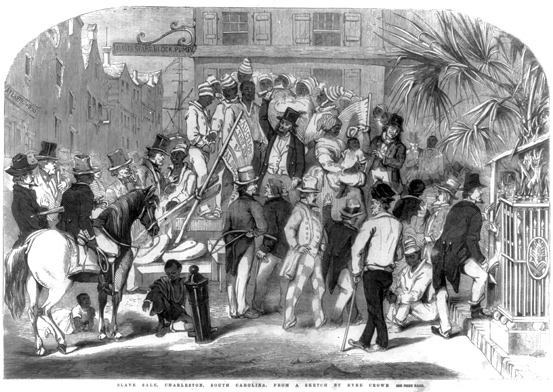

SLAVERY. Charleston was built on human bondage. For nearly 200 years, this place, often called the Holy City because of its multitude of churches, prospered as the American port where the greatest number of African slaves were dropped off, and sold. In 1770, half of Charleston’s population of 11,000 were slaves, and those slaves provided far more than just physical labor. Africans brought their knowledge about how to dye cloth with indigo, and how to cultivate rice, and thus Low Country plantation owners were able develop those products and so became enormously wealthy. By the Antebellum era, cotton plantations, which depended upon an enslaved labor force, had become the primary engine of Charleston’s economy. In 1820, Charleston’s population had burgeoned to 23,000, with an African majority.

THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION. In June of 1776, British naval forces attacked the hastily-built Fort Sullivan (now called Fort Moultrie), on an island in the harbor. Fortuitously, the walls of the fort (which were constructed of just-cut-and-not-yet-cured palmetto logs) absorbed General Henry Clinton’s fierce cannonball barrage: instead of shattering or setting fire to the battlements, the explosives were absorbed by the impenetrable walls, thus ensuring the South Carolinian reverence for the Mighty Palmetto, and the enduring image of the Palmetto tree on South Carolina’s state flag. But General Clinton’s second attempt to subdue Charleston met with better success. In 1780 he returned, this time with a formidable force of 14,000 soldiers. For the next two years, the British occupied Charleston.

THE CIVIL WAR. In 1860, South Carolina was the first of the states to vote to secede from the Union. A summary by Wikipedia’s boffins about the war’s beginnings will have to suffice for my little travelogue: “On April 12, 1861, shore batteries under the command of General Pierre G.T.Beauregard opened fire on the Union-held Fort Sumter in the harbor. After a 34-hour bombardment, Major Robert Anderson surrendered the fort, thus starting the war. Union forces repeatedly bombarded the city, causing vast damage. In 1865, Union forces moved into the city, and took control of many sites, including the United States Arsenal, which the Confederate Army had seized at the outbreak of the war.”

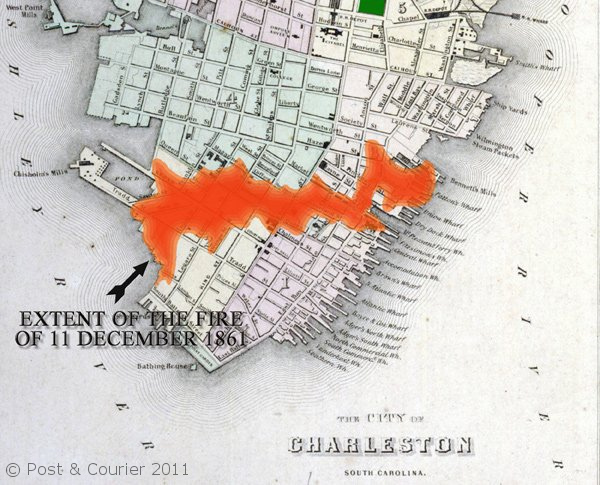

FIRE. And, to add insult to injury, in 1861 fire destroyed a third of the city. Per the POST & COURIER newspaper’s account of that disaster: “ Long before Charleston fell to the Union, the Great Fire of 1861 did nearly almost as much damage as the next four years of siege would. No one would ever know for sure how the fire started. Sometime before 10PM on Dec. 11, 1861, the flames seemed to appear in three places. There was never any chance to put it out. Firefighters had scant water to fight the fire; it started at dead low tide, which significantly cut down on their water supply. The city was left more dazed than an encroaching Union force from Beaufort had yet managed.”

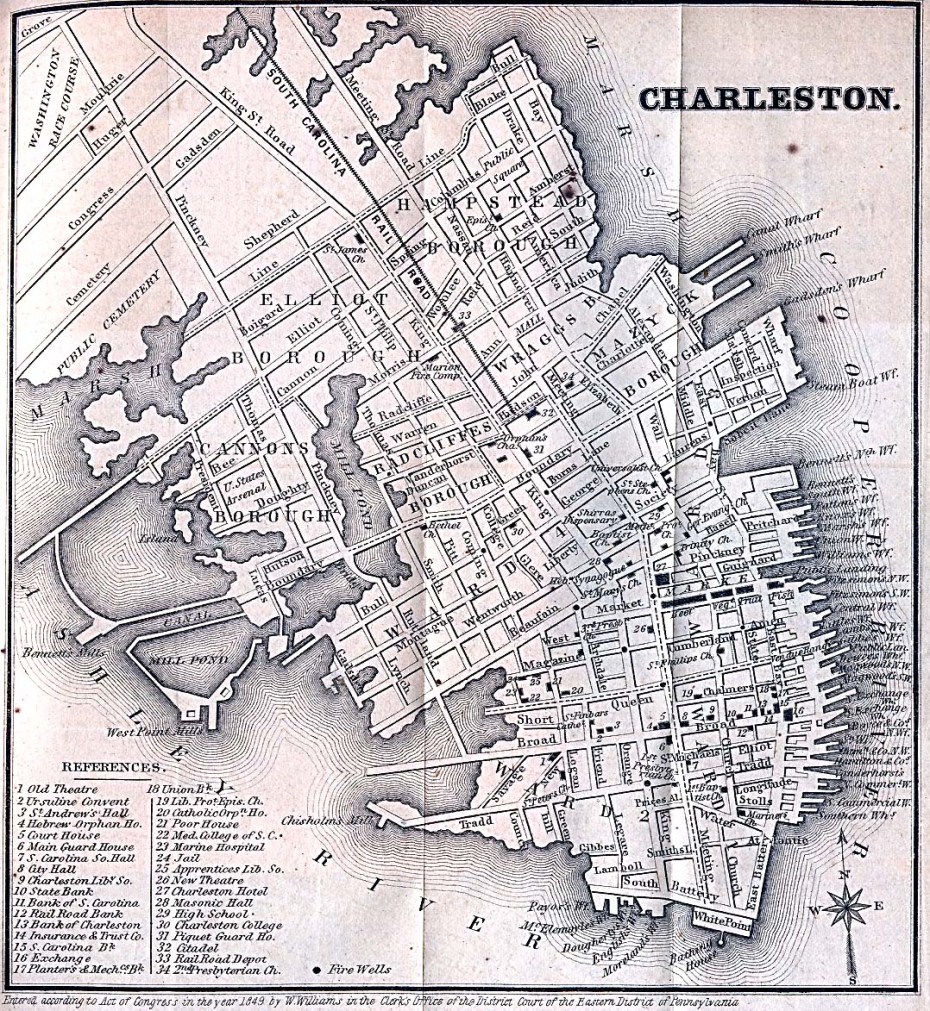

CYCLONE & FLOOD. As reported by the CHARLESTON YEARBOOK, on August 25, 1885, “Great Waves, rolling inward without resistance struck the sea wall of the Battery in swift succession, with a deafening roar, and bursting into water-spouts were hurled against the fronts of residences along the street, smashing in windows and doors, leveling fences and inundating the lawns and gardens.” This Street map, circa 1869, makes clear how vulnerable Charleston is to high waters and wind.

EARTHQUAKE & YET ANOTHER HURRICANE. Of course, Mother Nature wasn’t finished: on August 31, 1886 the great Woodstock Fault shifted to produce the most intense earthquake ever recorded on the Eastern Seaboard (7.3 on the Richter scale). The city, which by then had become home to 50,000 residents, was nearly destroyed. Clearly, Augusts haven’t been lucky times for Charleston…but September has also put the city through its paces. On Sept 21, 1989, Hurricane Hugo, the most violent to strike in 237 years, did its best to press Charleston to its knees. 3400 homes were destroyed, and ten thousand trees were uprooted. But as I walked through Charleston’s beautiful, now-well-healed (and obviously well-HEELED) neighborhoods South of Broad Street (a k a S.O.B.), all past insults to city’s fabric might well have only been bad dreams.

The damage at Hibernian Hall, on Meeting Street, after the 1886 Earthquake.

Photo, courtesy of CHARLESTON COME HELL OR HIGH WATER, by Whitelaw & Levkoff.

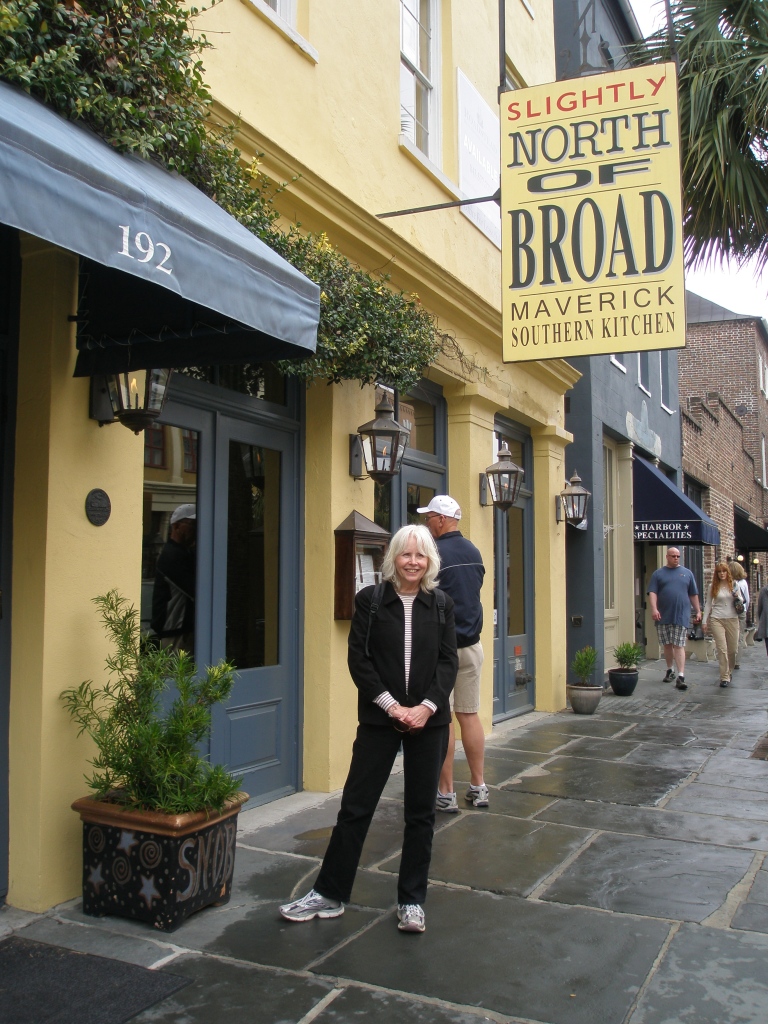

Having even a small inkling of these various tribulations can do nothing but increase a visitor’s admiration for the epic and ongoing resilience of Charleston’s inhabitants. And so, concluding what is probably the fastest (and least adequate) crash-course in Charleston History that’s even been attempted, I now resume our tour of the Historic District’s delights. Upon Donn’s arrival that Tuesday Noon, our first order of business was FOOD, and we proceeded slightly north of Broad Street, to the restaurant charmingly known as S.N.O.B., where the folks who run it are anything BUT.

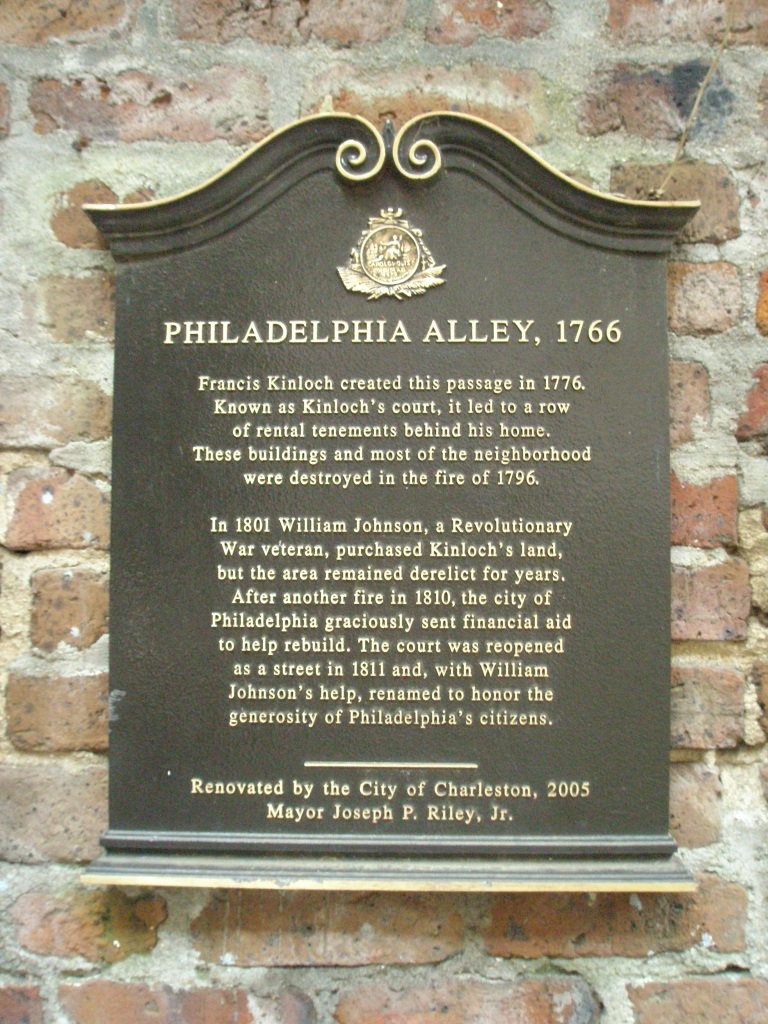

Bellies full with our on S.N.O.B.-feasts of red bean soup, and crab cakes, we began our exploration of the neighborhoods on the Harbor side of the Historic District. The air was warm, and the mist almost heavy enough to qualify as rain…a quite appropriate atmosphere for exploring Philadelphia Alley (extending between Queen and Cumberland Streets), which the supernaturally-inclined consider to be one of most-haunted spots in the city. In Michael Trouche’s CHARLESTON, YESTERDAY & TODAY, his sidebar on Charleston’s Forgotten Alleys says: “Some names have improved with time, such as Cow Alley, which was renamed ‘Philadelphia Alley’ in 1810. It became Charleston’s ‘dueling alley.’ Enemies would meet with pistols or sabers after mocking one another in city newspapers. Located behind the rear wall of St. Philip’s Church graveyard, Philadelphia Alley’s reputation for blood and gore far exceeds the actual record of duels. Honor was usually satisfied when either party was slightly wounded. An antebellum cotton warehouse bordering the alley has been used by a local theater group, the Footlight Players, in recent years. During rehearsals of a Civil War play in 1981, blank-loaded muskets were fired on a stage near the alley, causing rumors that dueling spirits had returned to settle unfinished business.” Really! Go buy Michael’s book!! And in the meantime, wander with us down Philadelphia Alley:

During the Revolutionary War, South Carolina’s troops flew a flag which was the same color blue as that of the militia’s uniforms, and was embellished with the same crescent that adorned their caps. In 1861, during the Civil War, an image of the Palmetto Tree (which had saved Fort Sullivan during the Revolutionary War) was added to the flag. From the Alley we proceeded to Waterfront Park, on the Harbor.

In Waterfront Park: the Pineapple Fountain, symbol of Charleston’s hospitality. This tranquil space was once a sprawl of busy wharves along the Harbor.

The day was getting short, and we hustled along the Promenade by the Battery toward the first of the two of the city’s grand homes that we hoped to tour.

The Seawall Promenade on the Battery, in Yesteryear, with Charleston’s busy Harbor in the background. Image courtesy of CHARLESTON COME HELL OR HIGH WATER, by Whitelaw & Levkoff.

The rain-soaked Live Oaks in White Point Garden. We’re looking toward Murray Blvd., which runs alongside the Ashley River.

But before stopping for a house tour, we zipped to the end of the Promenade, where the East Battery joins White Point Garden. Then, reversing direction, we paused outside of one the most admirable homes along the Promenade, the Robert William Roper House, at 9 East Battery. Unfortunately, our schedule didn’t allow for a tour of that property, which Jonathan Poston, in his BUILDINGS OF CHARLESTON informs us, was constructed in 1838-39, with an addition made in the late 19th century. This is “one of Charleston’s most monumental Greek Revival houses. With its prominent position on the southern edge of the Battery, its massive 5-columned Ionic portico could be seen by approaching ships miles away.”

Regretting that we had to bypass the Roper House, we retraced our steps along the Battery, to #21, where we entered the Edmondston-Alston House, one of city’s finest house-museums. The Middleton Place Foundation manages the property, which, to this day, continues to be occupied by a member of the Alston family….pretty nice digs, eh?

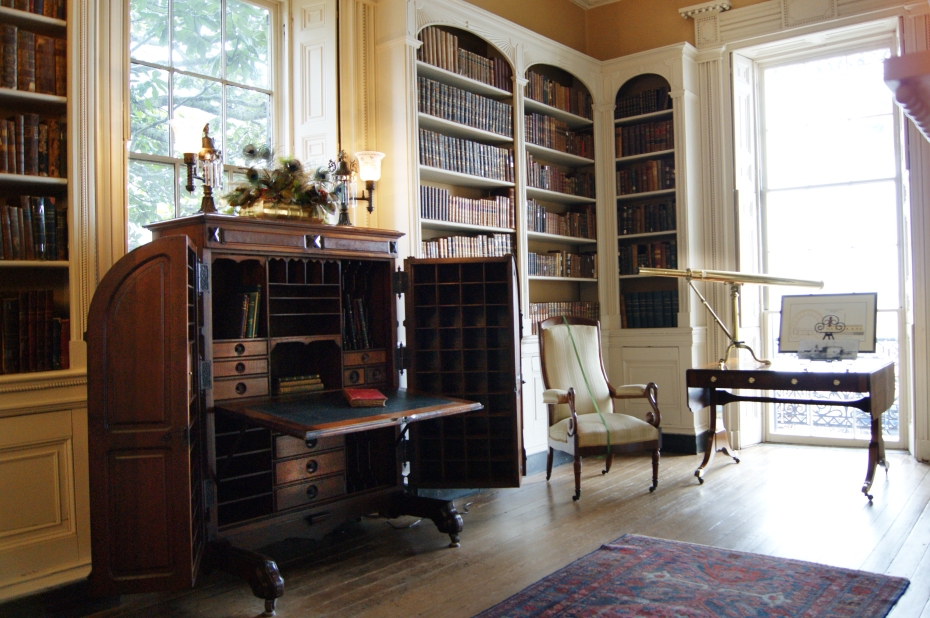

Per the Edmondston-Alston website, the “House (constructed in 1825 and enhanced in 1838) commands a magnificent view of Charleston Harbor. From its piazza, General P.T.Beauregard watched the fierce bombardment of Fort Sumter on April 12, 1861, signaling the start of the Civil War. And on December 11 of the same year, the house gave refuge to General Robert E. Lee the night a wide-spreading fire threatened his safety in a Charleston hotel.” (And we know what Hotel that was…and that the Hotel did in fact NOT burn, thanks to quick-thinking guests, who soaked every blanket they could find in the Hotel’s cisterns, and then draped those sodden coverlets over the outside of the building.) Following Charleston’s familiar economic pattern of boom and bust, Scottish shipping merchant Charles Edmondston wasn’t able to enjoy the grand house he’d built for very long. Financial reversals during the Panic of 1837 forced Edmondson to unload the property to “Charles Alston, a member of a well-established Low Country rice-planting dynasty. He quickly set about updating the architecture of his house in the Greek Revival style.” Visitors who tour the house today see the same Alston family furniture, china, silver, books and decorative objects that have been there since the Civil War. What’s most impressive is the sheer Good Taste of the Alstons! Each room is grand, but utterly welcoming. The second floor library, with its Harbor view, was almost too pleasant a space to leave. And somewhere along the way, during an Alston-Grand-Tour-of-Europe, literally thousands (if my memory serves, I think our guide set the number at a mind-boggling 7000) of Piranesi prints were purchased; many of those now decorate the walls of the House. Warren Cobb, of the Middleton Place Foundation, kindly provided me with these four photos of the house’s interior:

When our guide led us outside to the 2nd floor loggia, I was allowed to take pictures:

With time enough left for one more house tour, we skedaddled over to the spectacular Nathaniel Russell House, at 51 Meeting Street.

Front Entry to the Nathaniel Russell House, with the owner’s initials filigreed into the wrought iron balcony.

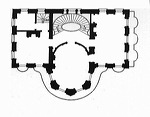

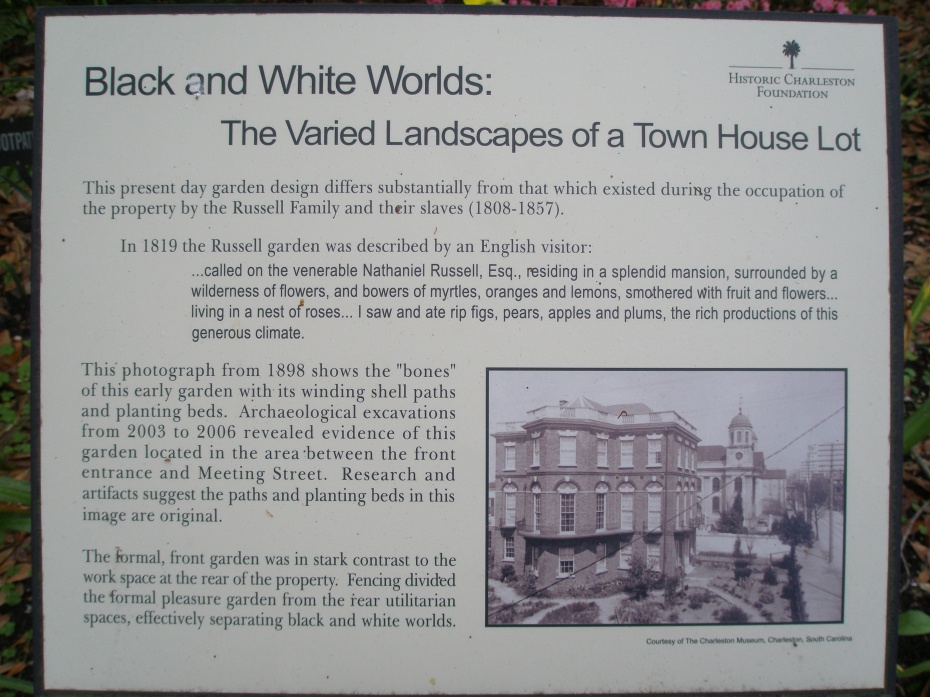

By way of introduction to this splendid property, I turn once again to Jonathon H.Poston’s BUILDINGS OF CHARLESTON: “Completed in 1808 on an original lot of Charleston’s Grand Modell, [Note: The Grand Modell, drawn up in 1672, assigned house lots in the city. ] the Nathaniel Russell House is recognized as one of America’s finest examples of Neoclassical domestic architecture. Its builder, Nathaniel Russell (1738—1820) was a prominent merchant from New England who came to Charleston as a young man of twenty-seven and quickly amassed a huge fortune. In landscape setting Russell’s house differs from most of Charleston’s early urban dwellings; it sits back from the street, creating a front garden entrance through which the house is entered at ground level. Wrought-iron balconies on the second-floor exterior wrap around the house and overlook the garden. The three-story house contains only three rooms on each floor. Each floor utilizes the geometric patterns of a square room, an oval room, and a rectangular room. A free-flying, or cantilever, staircase connects the three floors and is perhaps the most stunning interior architectural feature in the city.”

As is the case with most of Charleston’s house-museums, interior photography isn’t allowed. But Melissa Nelson, of the Historic Charleston Foundation, generously provided me with these six beautiful images of the main rooms:

Interior door between the front entry’s waiting room, and the great hallway that contains the free-flying staircase.

Oval Music Room on the second floor. It’s hard to prefer one room over another, but I admit that I love this space the best of all.

Since, by the time of our visit, the tulips had come and gone, I include this beginning-of-March view of the garden; also courtesy of the Historic Charleston Foundation.

Time and again as I journey, I’m reminded that the Travel Gods regard me kindly. As Donn and I climbed the cantilevered stairway, our guide mentioned that we were the second-to-last group of visitors who’d ever be allowed to set foot on those stairs. Apparently the 60,000 guests who each year clamber up the cleverly-built steps have proven to be too much for the old wood. Henceforth, all visitors will use an alternate stairway, and will have to content themselves with merely looking at this engineering marvel. This massive piece of precision woodworking was designed with great subtlety: as the stairs rise, each step is slightly smaller and slightly less heavy than the step immediately below it, thus allowing the huge structure to support itself. My head spins at the ingenuity of the architect, whose identity is unknown.

How had I managed to see all of this (and—truthfully–much, much more) on a single day? Sometimes my touring-stamina scares me… Donn and I finished off our day with a light but elegant meal at Poogan’s Porch, which is directly across from the Mills House Hotel, on Queen Street. As I remember my meal ( Arugula Salad with goat cheese crostini, pickled shallots, spiced pecans & fresh blackberries; followed by Fried Green Tomatoes with pecan encrusted goat cheese and fruit chutney) my mouth waters.

On that balmy Spring evening, we ate dinner on the front porch, right where Poogan, the dog who once claimed that spot, used to lounge.

On a sunny and crisply-cool Wednesday, we undertook a day-long excursion to four exquisite but very different Low Country Plantations. What we saw then will be the subject of my next Diary For Armchair Travelers. I’ll skip now to March 14th, our last day in South Carolina. The nippy temperatures which had chilled Charleston on Wednesday had become even nippier by Thursday morning. Stepping lively to keep warm, but gladdened by the bright sunshine, we set out on our morning tour with Michael Trouche, whose praises I’ve already sung. The cold had also delivered deep blue skies, and my Photographer-Self rejoiced. Finally… I’d be able to make some UN-gray and postcard-worthy portraits of the beautiful city. Herewith….my sunny-Thursday photos:

St.Philip’s Episcopal Church, 146 Church Street.

Built in 1835 by architect Joseph Hyde. Steeple added in 1848-50, by architect Edward Brickell White, who also designed the nearby French Hugenot Church. This steeple is one of the two most prominent in the city (the other being the steeple of St.Michael’s).

French Hugenot Church, 140 Church Street. This is the sole remaining congregation of Hugenots in America. A church has stood on this site since 1687. The present building, Charleston’s first Gothic Revival church, was designed by Edward Brickell White in 1844-45. During my visit, this Pink Confection was being refurbished.

Dock Street Theatre, 135 Church Street. The original structure was built in 1736, and was most likely only the second building constructed in America specifically for theatrical performances. At that time, today’s Church Street was “Dock Street;” adjacent to the Harbor’s busy docks. The current building was erected in 1809, and later on during that century was gussied up with its distinctive brownstone columns.

Dock Street Theatre. In 1809, this building also housed the Planter’s Hotel, whose proprietor is reputed to have been the mixmaster of the original Planter’s Punch.

A Cobble-Stoned Street. According to Michael Trouche, ladies whose pregnancies were becoming uncomfortably extended would hitch rides over Charleston’s more bumpy roads..the most of famous of which was nicknamed “Labor Lane.”

A Pineapple welcomes visitors, and a round Earthquake Plate adorns a wall. Earthquake plates anchor iron rods, which are inserted into the beams that support floors.

St. Michael’s Episcopal Church, 80 Meeting Street

(seen from a nearby plaza). Constructed 1752-61; interior completed 1772…and constantly renovated and restored, ever since. This white spire has long dominated the skyline, sometimes too much so. During the Civil War the church became an inviting target for Union projectiles, and was thus camouflaged with brown paint.

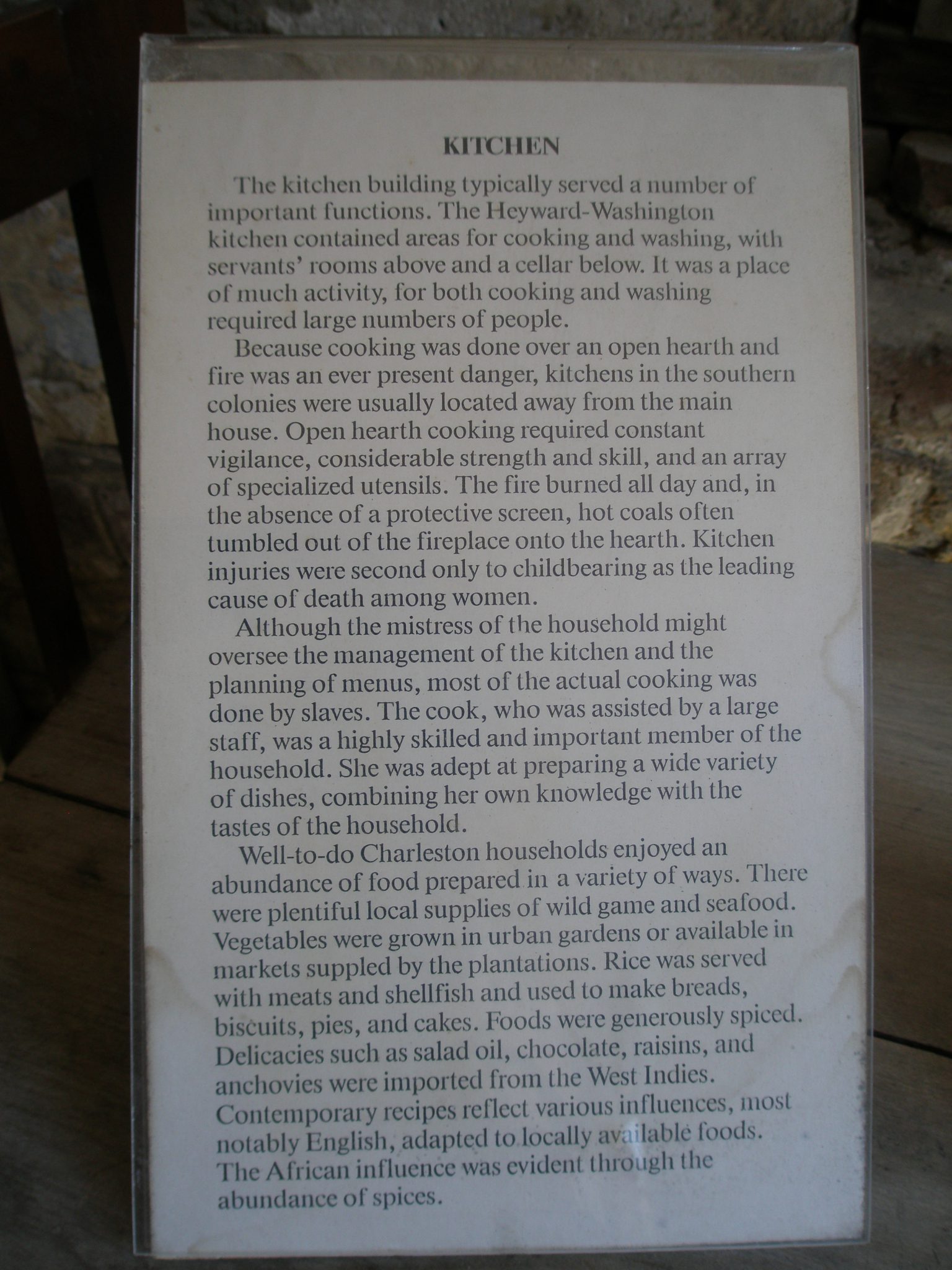

The Heyward-Washington House was Charleston’s first-established house-museum. Constructed circa 1771, it was basically wrecked by the late 19th century, and then completely restored to its 1771-appearance during 1929-30, after it was purchased by the Charleston Museum. George Washington occupied this house for merely a week, during his May 1791 visit to Charleston, but that visit was enough for his name to be added in perpetuity to that of the actual occupants–the Heywards—who were a wealthy rice-planting family.

Separate from the main house: the Kitchen & Laundry Building. As a method of fire-prevention,

most Charleston homes were built with outbuildings to contain

necessarily inflammatory activities such as cooking and heating water.

Of all the city gardens I ogled during my Charleston visit, the gardens behind the Heyward-Washington were the most sublime. As James R.Cothran reports in his GARDENS OF HISTORIC CHARLESTON: “When the house was purchased by the Charleston Museum in 1929, no vestige of a garden remained. In an effort to create a period garden that would complement the house and grounds, the late Emma Richardson was given the task of creating a garden that would exemplify a late eighteenth-century Charleston garden design. Since George Washington had […ever so briefly…] resided there in 1791, it was decided that only plants introduced into cultivation prior to that date should be used.” Over the years,the Garden Club of Charleston, advised by landscape architect Loutrel Briggs, has maintained and refined this Little Eden. Here, views of Charleston’s most beautiful city garden:

Now, as my final Charleston offering, a bouquet of images of the exquisite window boxes and front-door-step planters which adorn the Historic District.

Window boxes are essentially Gifts to Strangers, and the preponderance of these tiny but masterfully-composed gardens is Proof Positive of Charleston’s inherent generosity and civility. Coming Next: Donn and Greg and I travel to four Low Country plantations: Boone Hall; Middleton Place; Magnolia Gardens; & Drayton Hall.

Window boxes are essentially Gifts to Strangers, and the preponderance of these tiny but masterfully-composed gardens is Proof Positive of Charleston’s inherent generosity and civility. Coming Next: Donn and Greg and I travel to four Low Country plantations: Boone Hall; Middleton Place; Magnolia Gardens; & Drayton Hall.

Copyright 2013. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

4 Responses to Springtime Sauntering through Historic Charleston, South Carolina