December 2013

Now that the first traces of snow have settled upon New England, contemplating greenness—and gardens—seems more therapeutic than ever. Perhaps I’d dawdled about writing this report of my June trip to New York State’s Lower Hudson River Valley because I knew that the pleasure I’d get from thinking about those days would be greater, once wintertime had come.

My continuous quest for Significant Gardens isn’t being done merely to collect postcard-pretty-photos. I’m searching for built landscapes which have retained echoes of the spirits and minds that originally designed them. I’m seeking gardens that were made passionately and intelligently; gardens that have endured…despite passage of time (whether measured in decades or in centuries), cycles of seasons upon seasons, and inevitable changes-of-fortune. The Holy Grails in this search of mine are gardens that are simultaneously supple and refined; gardens where one’s initial pleasure at experiencing spaces and scents is matched afterwards by one’s satisfaction in learning about the intentions of the makers of those places. Intellectualism without sensuality becomes brittle. Sensuality without thoughtfulness becomes base. In the best gardens there’s a dialogue between the voluptuous and the ethereal, a conversation where these opposite qualities affect a garden-visitor so powerfully that ever afterwards, the wonder of having inhabited those spaces, however briefly, is transformed into memories which feed the soul. As I drove south along the Taconic Parkway I hoped that at least one of the gardens on my List might indeed be this marvelous…

But always, my first priority when I’m out and about is to find a quiet place where I can restore my energies and rest my head. In late afternoon, on June 5th, after taking a few seriously-wrong turns (no GPS for me….I’m strictly-paper-map), I arrived at The Millbrook Inn, which, continuing my good-travel-karma, turned out to be the most-top-notch of any B&B I’ve ever visited.

The Inn, a rambling white, clapboard farmhouse with interiors that have been completely renovated, is surrounded by verdant fields and mature woodlands in Millbrook, which is Serious Horse Country. I chose the Inn because of its proximity to Innisfree,the first of three gardens on my Hudson River Valley agenda, but as soon as I stepped into the Inn’s reception area, I realized that, for a traveler in need of comfort and serenity, the Inn itself is worthy of being called a Destination.

The Millbrook Inn. 3 Gifford Road, Millbrook, New York 12545. phone# (845) 605-1120.

www.themillbrookinn.com

Really…the floor in my bathroom was so impeccably clean that I could have eaten off of it without worry!

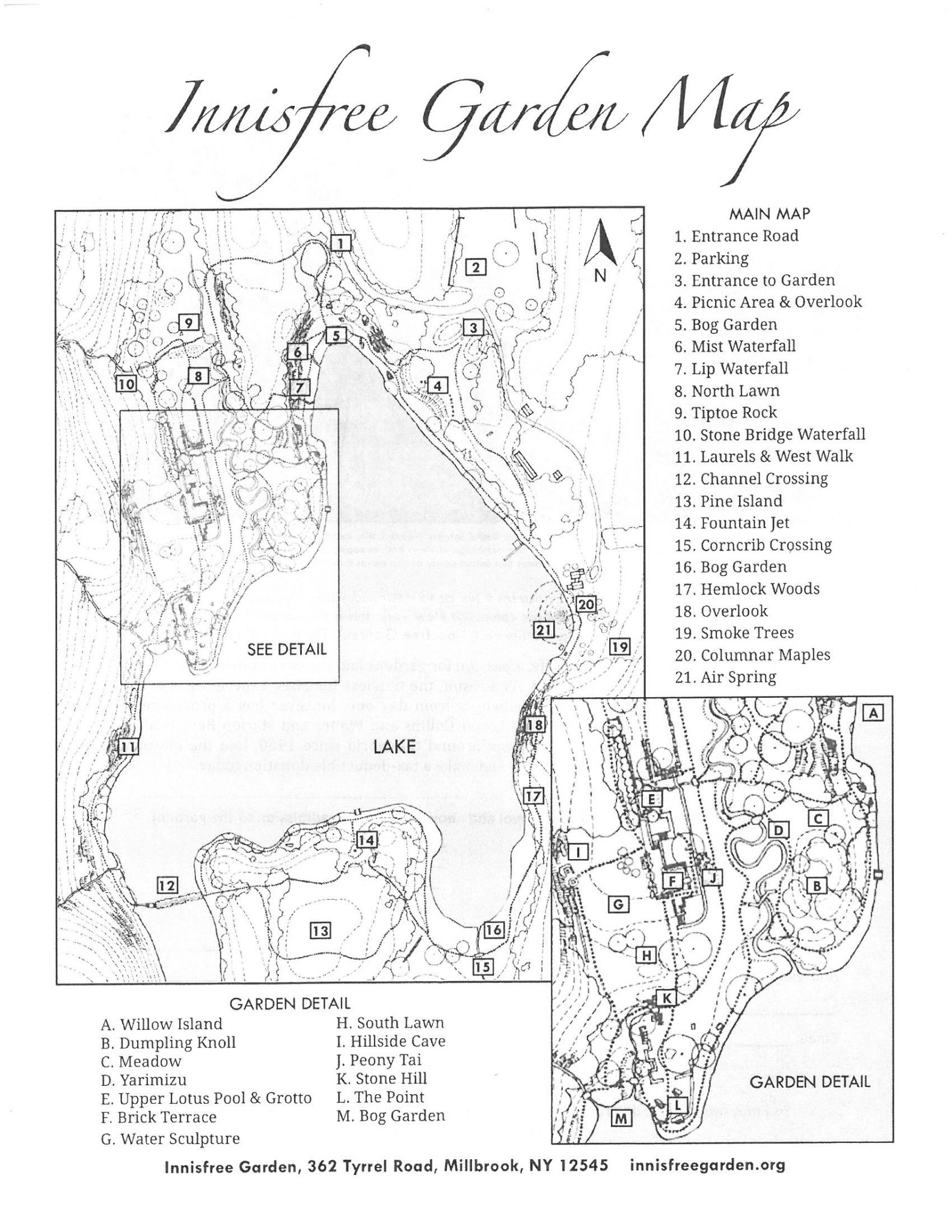

On the morning of June 6th, fortified by a Millbrook-Inn-Breakfast (aka “A Feast”), I made the 15 minute drive to Innisfree, which, now seen, I must certainly name as one of the most mesmerizing gardens of the world…and one upon whose grounds far-too-few garden-aficionados have trodden. During the four hours I spent at Innisfree, I crossed paths with no more than a half dozen other visitors. Granted, the day was overcast, but less-than-blue skies never inhibit serious garden-gawkers. Innisfree is a Public Garden in its purest form: no Information Center, no Café, no Guided Tours. Apart from an enthusiastic docent to collect one’s $5.00 admittance fee in exchange for a map of the grounds—and a single (but scrupulously-well-maintained) porta-potty at the far edge of the parking lot—there’s nothing there but the Great Outdoors. But however graceful and natural those 185 acres that surround a glacial lake seem, one must not be hoodwinked. The stroll-gardens at Innisfree are mind-boggling demonstrations of garden-design artifice: of land-shaping and mood-making executed in most subtle and cunning fashion. Who were the tricksters who made this enchanted landscape?

As always, I refrain from wheel-reinvention, and so quote the Innisfree Foundation’s summary of the Garden’s history:

“Over fifty years in the making, Innisfree is a powerful icon in 20th century landscape design.Largely the work of landscape architect Lester Collins (1914-1993), with important contributions by his client, the artist Walter Beck, it is a site-specific distillation of Modernist ideas with traditional Chinese and Japanese garden design principles.”

“In the late 1920’s, Walter Beck and his wife Marion (nee Burt), an heiress, began work on Innisfree, their country residence. Walter Beck’s fascination with Asian art….led him to Chinese and Japanese garden design, which became his lasting inspiration for Innisfree. In 1930, Beck discovered the work of eighth-century Chinese poet, painter, and garden maker, Wang Wei. Beck observed that Wang created carefully defined, inwardly focused gardens and garden vignettes. Thinking of these as ‘cup gardens,’ Beck took great pleasure in creating small, three-dimensional pictures at Innisfree, often incorporating rocks from the site and horticultural advice from his wife. Unlike Wang Wei…Beck gave little thought to how his creations related to each other or the landscape as a whole. This was the genius of Lester Collins.”

“Walter and Marion Beck met Lester Collins early in 1938 when Collins was an undergraduate at Harvard, and they were soon working together on the Millbrook landscape.” After extensive travels throughout Asia, during which Collins worked with a

“Japanese scholar to translate the 1000 year old SENSAI HISHO, the seminal SECRET GARDEN BOOK, which urges gardeners to study nature and great gardens but to build the essence rather than the copy,” Collins returned to the U.S. to go into private practice, and also continued his work at Innisfree.

“Innisfree is perhaps unique as the creation of a single, major landscape architect in its incarnations both as a private and a public garden. Organizationally, Lester Collins helped the Becks craft the original mission for the Innisfree Foundation and then shaped the nonprofit that exists today. Throughout his fifty-year association with the garden, Lester Collins evidenced a superb ability to sculpt the land and choreograph movement through space. Drawing on these particular skills as a landscape architect, as well as the Alice in Wonderland aspects of traditional Chinese and Japanese gardens, the jazz-like syncopations of Modernism, and the ideas of occult or asymmetrical balance common to all three, Collins created the dreamlike sequence of vignettes that defines Innisfree.”

Of course none of these syntheses would have been possible without the perfect setting first provided by the Becks’ lake and acreage in Millbrook. Any Chinese garden worth its salt has to represent Nature’s totality, with a harmony of water and mountains. And so Innisfree’s deep and calm lake became the heart and the focus for the hills and the substantial granite cliffs that circled it. The Yin (receptive and yielding) and Yang (upright and hard) of things were in place, ready for the eccentric, creative energies of the designers.

I passed the Picnic Area and Overlook…

…and the Entrance to the Garden…

…and followed the Lake Path…

…past the Bog Garden…

…toward the base of the Mist Waterfall. Beck had to do quite a bit of tinkering to find a way for a water jet to produce just the right pressure and volume for misting.

The Mist Waterfall itself seems utterly natural, although one knows it cannot be.

The Mist Waterfall. In Chinese gardens, rainbows and mist are feminine, and associated with the supernatural powers of fertility.

At the Lip Waterfall, Beck modulated the flow of water over rocks to create subtle variations of sound.

Up the steps by Tiptoe Rock…

…and down the other side of the hill toward the North Lawn:

North Lawn. All of the berms throughout the Gardens were designed by Lester Collins, and have been built since 1980.

Even with a Map of Innisfree in hand, it had taken me only 15 minutes to become disoriented. Instead of continuing around the edge of the Lake, I’d climbed the mossy stone steps near the Mist Waterfall up to Tiptoe Rock, and then tripped down the back side of the hill into the North Lawn, where I found undulating grassy hillocks which were hemmed in by steep slopes of deciduous trees. With no points of reference—the Lake had disappeared, I hadn’t long views of any of the other garden areas indicated on the Map, and the white glare of an overcast sky obscured the position of the sun—my sense of direction had vanished. This part of Innisfree proved impossible to photograph. The abrupt compression of space, and the funhouse-like level-variations of the mounds: these qualities that most define this particular ‘cup garden’ could NOT be captured by my (very good) camera lens, which somehow smoothed and lessened the contrasts. Moral: enjoy my pictures, but lace up your hiking boots and get yourself to Innisfree.

Much later, back home, and buttressed by piles of reference books—particularly by Maggie Keswick’s superb study of THE CHINESE GARDEN—I began to make sense of how Chinese landscape painting had influenced the gardens at Innisfree.Per Keswick:

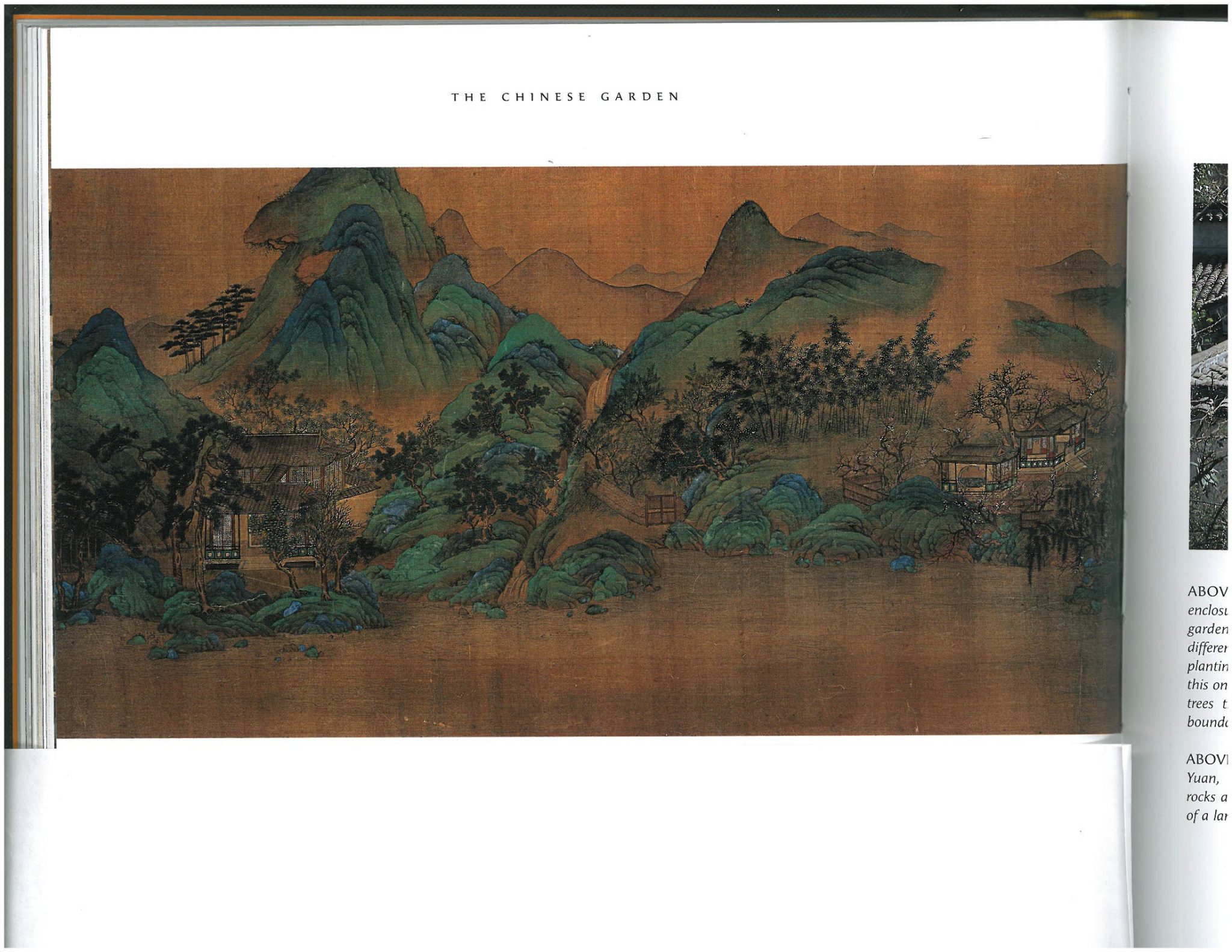

“Unfortunately, none of Wang Wei’s original works survive.” [Note: Walter Beck studied copies-of-copies-of-copies of Wang’s scrolls.] “Wang Wei is sometimes credited with inventing a new format: the scroll painting which one unwinds from right to left. Each space is separated, but linked to the next by water and mist.”

Wang Chuan scroll (detail). Copy after Wang Wei (699–791). Image courtesy of THE CHINESE GARDEN, by Maggie Keswick.

In Chinese gardens, “there is no overwhelming sense of an ending, as there is at the Palace of Versailles. Although there is a complicated order that can finally be perceived, the Chinese did not lay out their gardens to be conceptualized from above, as the French or Italians did. The Chinese garden was to be perceived as a linear sequence—the scroll painting you enter in fancy—that seems infinite. The internal boundaries were made to feel vague or ambiguous, time was made to stop and space become limitless.” A proper Chinese garden had “deliberately confusing boundaries, no clear order, and certainly no symmetry.”

SO….instead of plummeting down a rabbit hole, I’d climbed up and over a rocky crag, breathed the moist air of a Mist Waterfall, stepped carefully down alongside the banks of an iris-lined brook, and strolled out onto a vast, undulating, funhouse lawn. I’d arrived at a place which seemed divorced from the reality of the Hudson River Valley.

Not until I’d reached the top of the North Lawn did long views reappear…

…but this landscape, which at first had seemed quite normal, suddenly became anything BUT:

I heard a hissing sound, which confused me, and I strained my eyes to locate the source, which seemed to be uphill, past a grove of severely-pruned Gingko Trees. Clouds of steam were the cause of the sound: they billowed from a huge, columnar sculpture. I walked toward the cloud, and then into it. I cooled myself in the mist, and looked upward toward the hazy sky, through an artificial rainbow.

Another view of the recently-installed Steam Column, which looks as if it’s constructed of kor ten steel…but which is actually painted wood.

Gingko biloba. The Gingko was discovered in China (probably in 1879) by plant explorer Ernest Wilson

Just uphill from the Steam Column is a Hillside Cave…

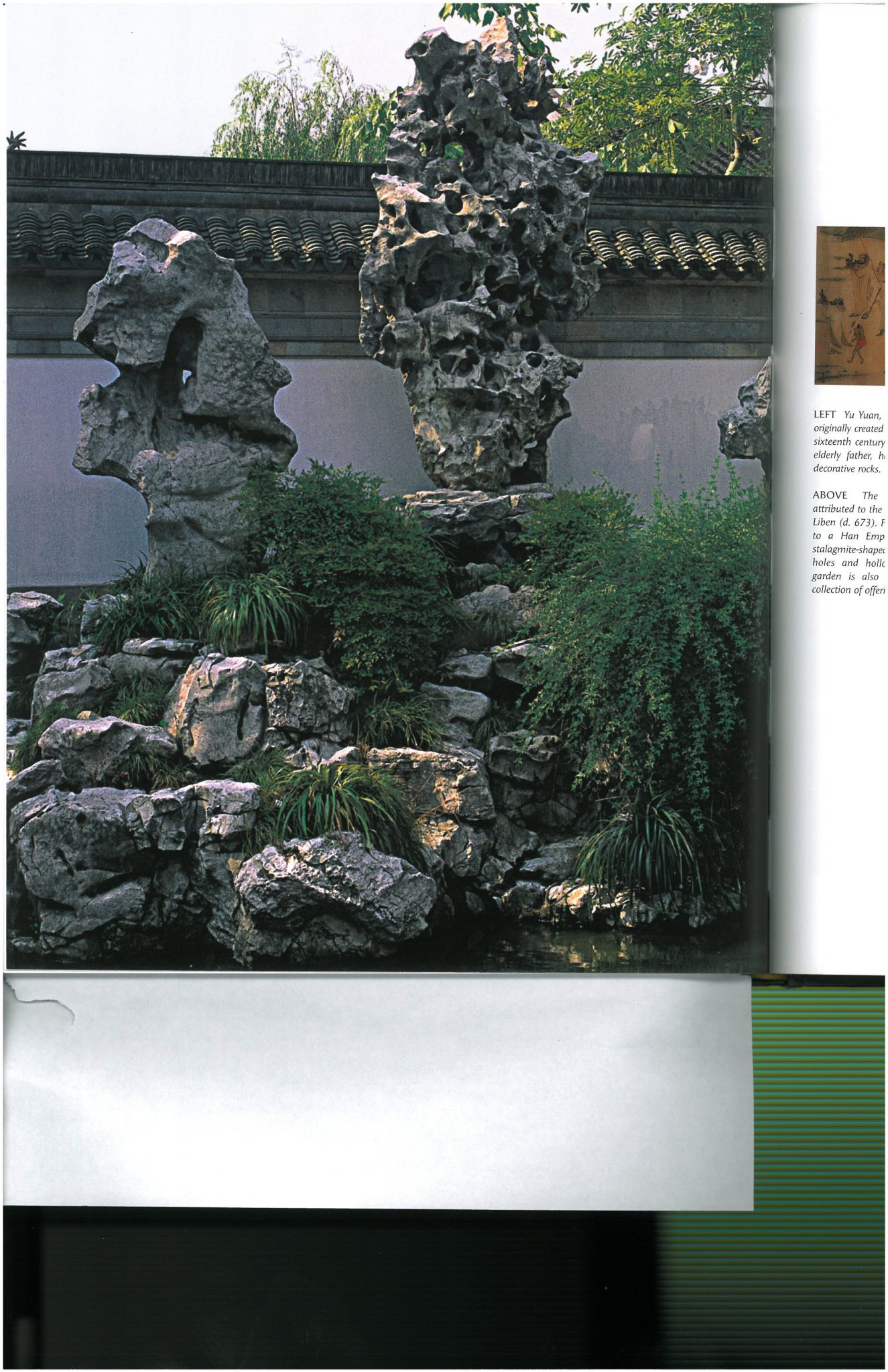

…and nearby is a wall festooned with climbing hydrangeas, and punctuated with a circular grotto, with rocks chosen and mounted by Walter Beck. Lester Collins was undoubtably responsible for linking Walter Beck’s many “cup gardens” into a coherent whole, but Beck’s particular genius was in his appreciation, and inspired placement of, the countless specimens of rocks—mostly large….VERY large—which serve as the Garden’s sculptural adornments. As Maggie Keswick writes:

“The Chinese have loved and revered rocks almost in a way that we have admired and collected religious icons. Stone-loving began in ancient times when mountains seemed to be imbued with supernatural power. Large and strangely-shaped boulders were felt to be powerful and were worshipped as local gods. Appreciation of single rocks…was elevated to connoisseurship.”

Typical decorative use of large rocks; these in China’s Yu Garden, which was built in the 16th century. Image courtesy of THE CHINESE GARDEN, by Maggie Keswick.

Throughout the ages, Chinese nobility spent untold fortunes to acquire, move, and then mount enormous boulders, and we can be certain that Walter Beck also spared no expense when it came to providing Rocks of Character for his beloved Innisfree.

Circular Grotto. Walter Beck’s particular genius lay in his choice, and positioning of, rocks on his property.

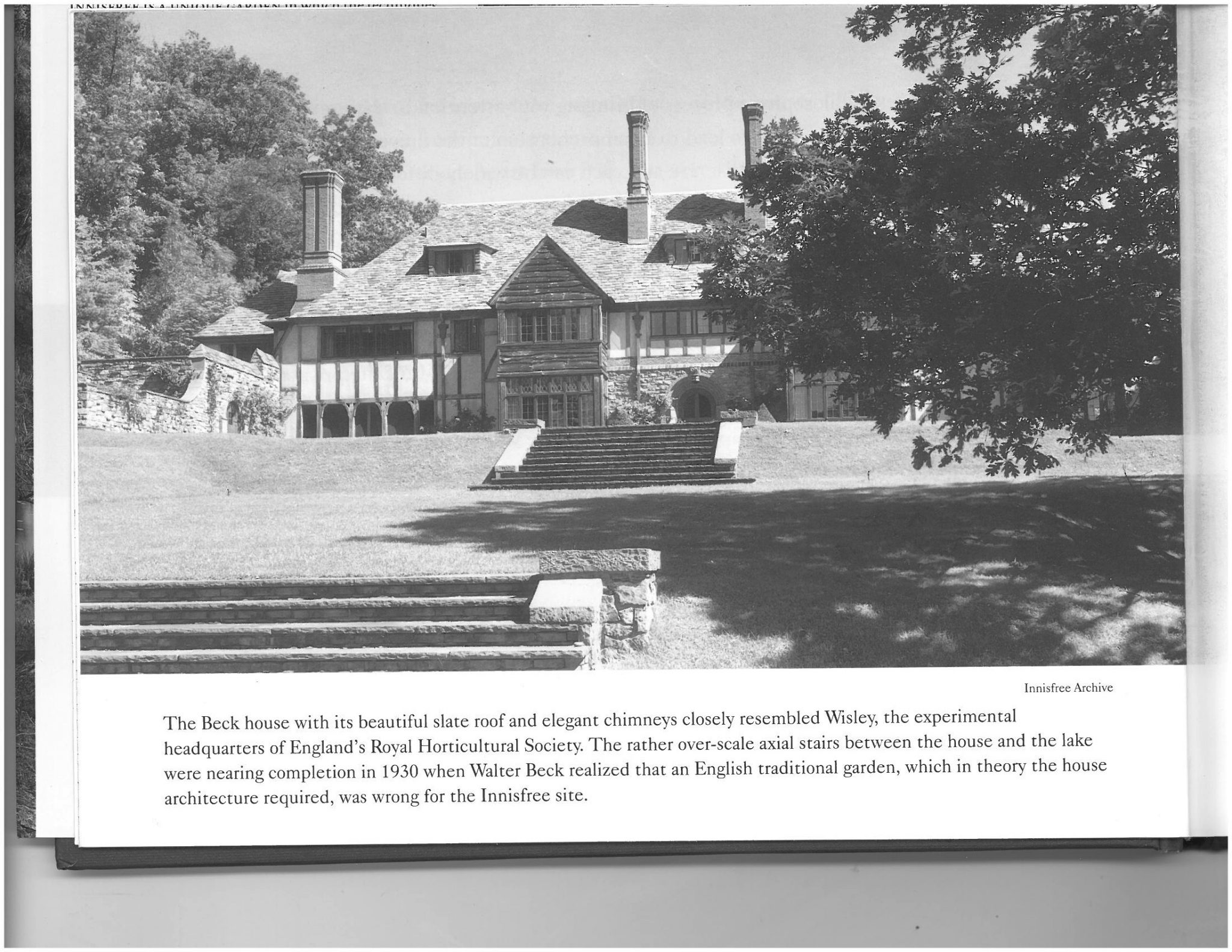

When Walter and Marion Beck first moved to Innisfree, they built their home just east of the area now occupied by the Gingko Trees and Steam Column. The style of their house, a reproduction of Wisley, the experimental headquarters of England’s Royal Horticultural Society, had no relevance to the Asian-inspired gardens that sprang up around it. In 1982, once both Walter and then Marion had died, Lester Collins had the structure razed.

The home of Marion and Walter Beck. Image courtesy of INNISFREE: AN AMERICAN GARDEN, by Lester Collins

In today’s garden, the Brick Terrace is all that remains of the Beck homestead.

Walter Beck crafted the decorations for the Brick Terrace…

…and supervised the construction of the retaining walls and stairs in the gardens that abutted his house.

Down-slope from the Brick Terrace is the Peony Tai:

From the Peony Tai, the Meadow below, with its undulating Yarimzu (or Oxbow Stream) can be seen. The Meadow Garden and Stream were the most elaborate and costly of Lester Collins’ designs for Innisfree. Once again, photographs cannot adequately describe the sense of surprise—and then delight— that come with one’s first glimpse of this fairy-tale scene.

The Serene slopes of the South Lawn:

Walter Beck built a Stone Hill at the base of the South Lawn:

The formations at The Point are Walter Beck’s most famous uses of rock.

The 3 large rocks on The Point are named: Turtle Rock (left). Dragon Rock (center). Owl Rock (right). Image courtesy of the Innisfree Foundation.

Leaving The Point, the West Walk skirts the Lake…

…and leads to the Channel Crossing Bridge…

…which delivers us to Pine Island. A single, 60-foot high jet of water, which leans with the winds, is the visual and emotional anchor of the Island. Although traditional Chinese gardens rarely included fountains and other water amusements, Walter Beck’s restrained use of fountains throughout the garden is consistent with the habit of China’s Emperors, who delighted in carefully-placed water-toys (aka “Hydraulic Elegancies”).

A Foo Dog guards the path to the Corncrib Crossing…

…which passes a Bog Garden…

…and points us to the Hemlock Woods overlooking the Lake.

Our stroll around the Lake comes to an end as we approach the great Willow, and five Columnar Sugar Maples…

…and the Pink Haze of the Smoke Trees.

As I hiked through the Gardens, I assigned myself the exercise of picking a spot, and stopping. I’d stand and stare at the vista before me. Then I’d turn 45 degrees and stare again. After giving myself many, full-360-degree looks throughout Innisfree, I discovered that, from no angles were the views anything but varied and beautiful and thought-provoking. This is truly a garden that’s designed to be lingered in, to be puzzled by, to be entered “in fancy”…a place that’s simultaneously calming and exciting.

I’ve photographed many gardens, but no garden has posed such picture-taking challenges as Innisfree did on that hazy Wednesday in June. Certainly, I was able to capture images of great beauty, but the gardens in Millbrook have a soul, a gentleness, and a good humor—-along with deep contradictions–which can neither be explained by pixels, nor contained by a frame. Perhaps only the ancient art form of a scrolled, painted landscape could begin to suggest the atmospheres there. I would dearly like to see how 21st century scroll-painters might depict Innisfree’s shy corners and moody panoramas.

Even though the designers are long gone, Innisfree continues to evolve with the help of Lester Collins’ wife. Petronella Collins is President of the Innisfree Foundation, and each summer she takes up residence…the better to oversee her small staff, and to guide the subtle developments which continue to transform the gardens.

With his “cup gardens,” Walter Beck created a series of freestanding jewels. With the broad strokes of his landscaping, Lester Collins threaded those jewels into a magical necklace, one which glimmers on the slopes of a hidden and tranquil Lake. If you’re still fleet of foot, love gardens, and haven’t yet been to Innisfree, please find time to make your way to Millbrook. Be sure to wear sturdy shoes, and barricade your body behind long sleeves and trousers and high socks…because (alas), no matter how lovely your thoughts, or how beautiful the scenery, ticks abound in New York State. Yessir…BUGS will always drag us down to Earth, and back to Reality.

Innisfree Garden

Open from early May to late October

Wednesday through Friday: 10AM to 4PM

Weekends and Holidays: 11AM to 5PM

362 Tyrrel Road, Millbrook, New York 12545

www.innisfreegarden.org

Coming Next: Part Two of Hudson River Valley Gardens—Stonecrop, a plant-lover’s paradise; and then Kykuit, the Rockefeller-extravaganza in the Pocantico Hills.

Copyright 2013. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express &

written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

4 Responses to Hudson River Valley Gardens: Part One–Innisfree