A glimpse of Bathrooms-to-come, at the Crane Estate’s Great House. In the Apricot Guest Room: perfectly book-matched marble slabs & sterling-silver fixtures. This is Bathing-Heaven, circa 1928.

October 2014.

I’m constantly transporting my mind to far-off places…whether I’m plotting my next trip abroad, or I’m reviewing photos taken and books gathered on past journeys, as I compose my Diaries for Armchair Travelers. But occasionally, I stop all of that distant-lands musing, and instead remind myself to dig for the treasures in my own back yard. And if I forget to open my eyes to what’s local…or at least to what’s in my same time zone…someone else will rap me on the skull, and suggest a destination that’s a day’s drive from my New Hampshire home. And so ensued my three August visits to the Crane Estate, on Castle Hill, in the seaside village of Ipswich, Massachusetts.

Settle yourself into a comfortable chair and I’ll tell you a meandering tale about how and why my fascination with the Crane Estate began. In October of 2013, I published a Diary about Fletcher Steele’s hugely influential gardens at Naumkeag, in Stockbridge, Massachusetts.

( If you’ve got an ounce of stamina to spare, once you’re done with our Ipswich visit, follow this link to the Stockbridge article: GRAND GARDENS OF THE BERKSHIRE HILLS. )

Grand Gardens of the Berkshire Hills: Fletcher Steele’s Naumkeag, & Edith Wharton’s The Mount

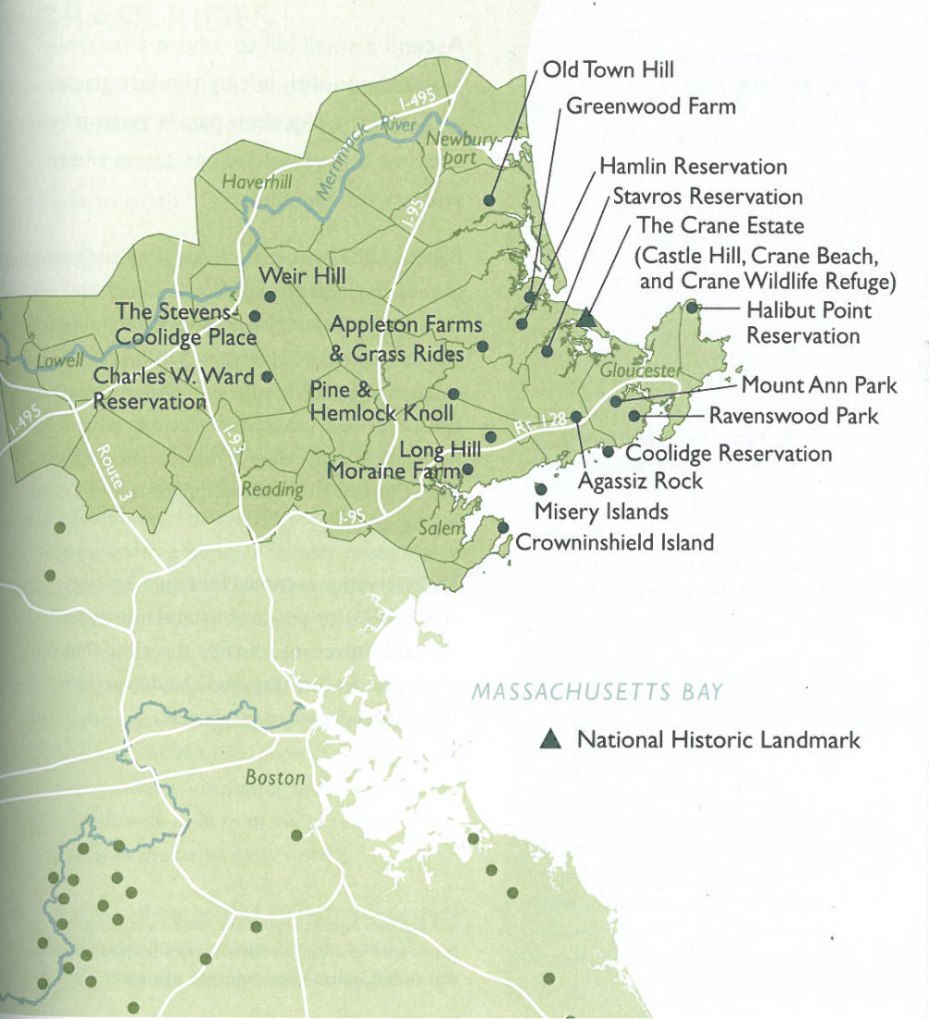

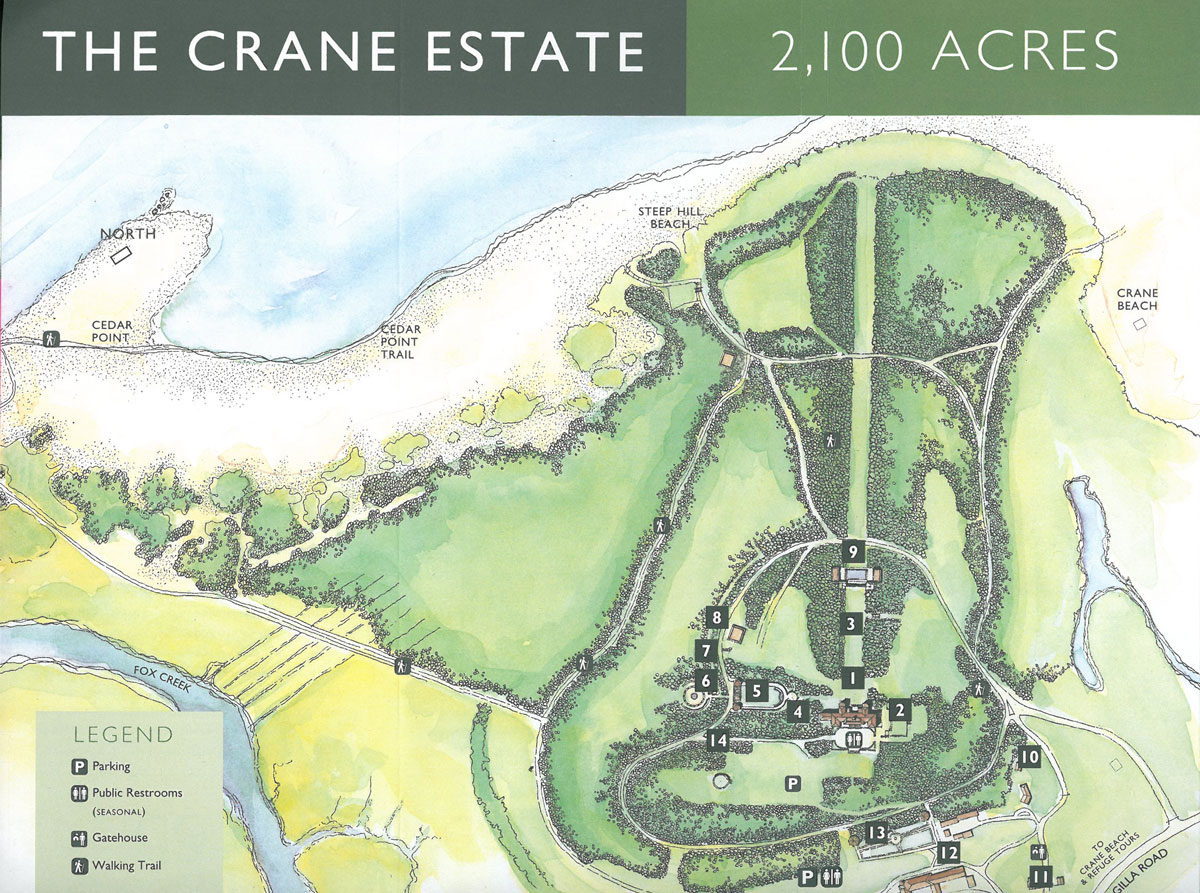

My Fletcher Steele piece drew the attention of the Trustees of Reservations, who own Naumkeag, and their Public Relations Director Kristi Perry asked if I’d consider visiting the Crane Estate, one of the finest homes from America’s Country Place Era, and another of the Trustees’ cherished properties. The holdings of The Trustees of Reservations are considerable, and include over 100 estates, gardens, and tracts of land across Massachusetts. The Trustees ( www.thetrustees.org ) have been at their business of saving properties of scenic, historic and ecological value for quite a while: established in 1890, they’re the oldest land preservation organization in America.

Map of the Northeast Massachusetts holdings of the Trustees of Reservations. The Crane Estate, marked with a triangle, is also a National Historic Landmark. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations.

Per usual, life intervened, my much-farther-afield wanderings continued, and nearly a year passed after Kristi’s overture to me. I confess I also did a bit of foot-dragging about scheduling a visit to Ipswich as I began to fuzzily recall my last visit to the Crane Estate…made well over 30 years ago, when I had attended a wedding dinner, on the oceanside terrace, at twilight. [Note: the Crane Estate has long been a venue for weddings.] My memory from that ancient visit was of a somnolent and indefinably spooky hilltop manor whose dimly lit ballroom and romantic but crumbling gardens were only temporarily enlivened by the music and dancing and chatter at my friends’ celebration.

BUT…excited by the prospect of inspecting the recent improvements to the Crane Estate’s spectacular grounds (which, after much neglect, are being restored), and intrigued by an invitation for a private look at the Great House, which would be led by Castle Hill’s charming and erudite Engagement Manager Pilar Garro, I finally carved out time for a visit. On August 12th, as I drove toward the North Shore of Massachusetts, I had no inkling that the day’s explorations would merely whet my appetite; that I’d soon become a frequent commuter to Castle Hill, instead of a one-time visitor…

I first passed through the village of Ipswich, which was settled in 1633, and where, to this day, more than 55 houses built between 1625 and 1725 (a stretch of time known as the First Period) are still occupied. [Note: Worry not. Modern amenities HAVE been added to those antique structures. Writing about the Cranes–whose name is synonymous with bathrooms–does make one begin to obsess about proper facilities, as you’ll soon see…] Prior to the American Revolution, Ipswich was one of the major Atlantic seaports in the northeast, but, as ships became larger, its shallow river, which empties into Ipswich Bay and Plum Island Sound, could no longer accommodate those vessels. The better, deeper ports of nearby Salem and Boston prospered, while Ipswich’s economy stagnated.

Not until 1828, when the buildings of Ipswich Mills were erected along the banks of the river (where the water power of the Falls could be harnessed), did the Industrial Revolution roll into town.

Here are some photos taken in the Village, during my August 25th visit.

Pedestrian bridge across the Ipswich River, leading to the new River Walk, and the old mill buildings.

From the River Walk., one glimpses colorful murals, which have been painted on the old mill buildings.

In 2007, Alan Pearsall completed his painted History of Ipswich, which covers two sides of the old mill building complex.

Sylvania Sally, of the Sylvania Paint Shop: a business that occupied part of the former Ipswich Hosiery Mills.

Thus, for a time, Ipswich had the distinction of being America’s foremost producer of lace, and later on, of hosiery. But even that burst of vitality was eventually siphoned off by Lawrence and Lowell: nearby cities where the factories along the Merrimack River were larger, and more numerous. Once again, while the rest of Massachusetts boomed, Ipswich slept.

At the corner of Market and Central Streets, the 5 Corners Cafe is the best place to grab some lunch.

www.fivecornerscafeanddeli.com

These prolonged, unintentional slumbers have proven to be Ipswich’s greatest gifts to posterity. Because, at critical junctures, development bypassed the village, great expanses of forest and farmland and wetlands remained intact, and so now, 380 years later, today’s visitors can marvel at many of the same beautiful landscapes and animal habitats that first enticed the British settlers who established their homesteads on the fertile hillocks and lowlands that hugged the shores of the Atlantic Ocean.

Apart from the local excitement generated by the lavish Houses-That-Crane-Built-Upon-Castle-Hill (which I’ll soon describe), the other major disturbance in Ipswich’s 20th century social history was caused by John Updike. As recounted by William M.Varrell for the Ipswich Historical Society, “John Updike, Ipswich’s Pulitzer Prize winning author, lived in town from 1957 to 1974. He often wrote about the town…and many consider his finest local contribution to be the best-selling novel COUPLES. It stood the town on its ear, as many speculated on which local inhabitants were represented by his most colorful characters.”

It seems fitting that when Updike’s 1984 novel THE WITCHES OF EASTWICK was transformed into the 1987 film of the same name, the primary exterior location shots were done on the grounds of the Crane Estate (a smidgen more about this too, in a while…).

Until the Crane family built their summer retreat in Ipswich, the standard for excellence in residential housing in the Village was measured against the High Federal elegance of the Heard House, which was completed in 1800. Now the headquarters of the Ipswich Historical Society

( www.ipswichmuseum.org ) , the Heard House was the rambling home of John T.Heard, and his baker’s dozen of 13 children (Mr.Heard exhausted two wives, both of whom died before the House was occupied).

The front elevation of the Heard House, a Federal Style mansion that is now the home of the Ipswich Historical Society.

Heard House, circa 1940. When Mr. Heard’s home became too small for his family, additional rooms were constructed to the rear of the main building. Image courtesy of the Ipswich Historical Society.

Directly across South Main Street from the Heard House is this reproduction of a 1657 house, built during the First Period. This structure is also part of the Ipswich Historical Society’s complex of buildings.

Adjacent to the reproduction of the very modest First Period house is the Whipple House, which the Ipswich Historical Society considers the crown jewel of their historic house collection. The left side of the Whipple House was built in 1655, and the right side added in 1670.

On the lawn of the Whipple House, my nephew Leo Quick demonstrated proper use of the stocks, during our August 16th visit to Ipswich.

After I’d acquainted myself with the discreet charms of Ipswich Village, I followed Argilla Road, a winding country lane which led me past a tree-lined river, and then across rolling farmlands, and finally through marshlands abloom with goldenrod and purple loosestrife (a beautiful but thuggish wildflower). I lowered my car windows and breathed deeply: of air that was perfumed with the mixed scents of pine trees and field grasses and ocean salt. On each of those three August visits, the weather was the stuff of which summer postcards are made : sunny, dry, warm and breezy. Inhabiting that landscape, on those days, made me certain that, just then, nowhere else on Earth could be more perfect. I understood why, a bit more than 100 years ago, the Crane family, who hailed from Chicago, had chosen to build their summer retreat here, amid this quintessentially New England scenery.

I turned off Argilla Road, by the property’s gates, and looked upwards, hoping to catch a glimpse of the Great House, but, from roadside, the House remains hidden.

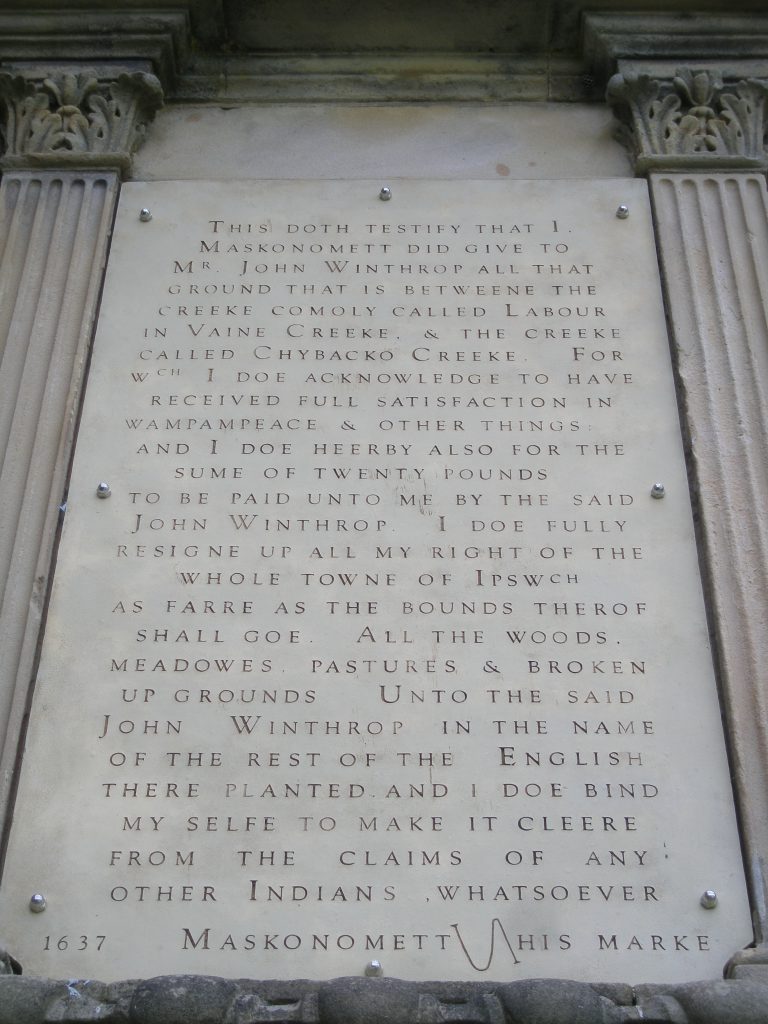

A circuitous driveway led me away from the salt marshes, and up onto a pine and oak covered drumlin. Since 1637, when Maskonomett, Chief of the Agawam tribe, sold his ”woods, meadowes, pastures and broken up grounds” to John Winthrop Jr (son of the Massachusetts Bay Colony’s first governor), the hillock upon which the Crane Estate now rests has been called Castle Hill. Maskonomett parted with this prime bit of real estate for the sum of twenty pounds (I hear you groan—as do I—at this criminally meagre payment).

This historical plaque, which records the Sorry Deed, is mounted on the southeast side of the Great House at Castle Hill.

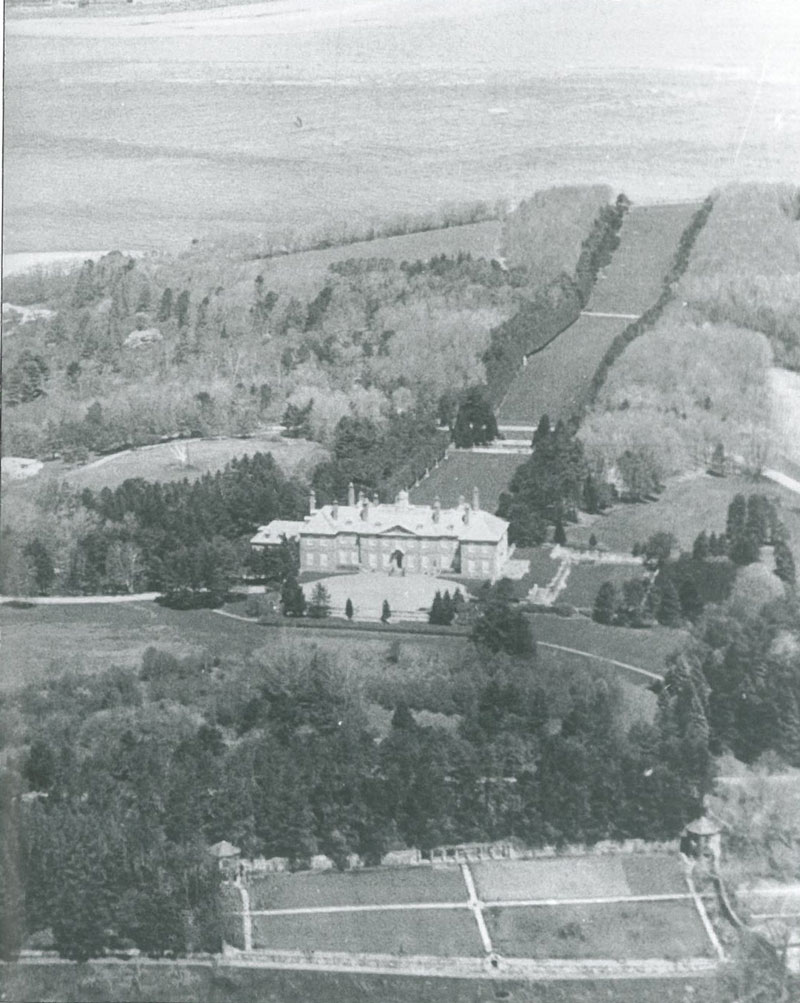

The cover of the Crane Estate’s brochure. This aerial view of Castle Hill and Castle Neck shows the great expanse of land that Chief Maskonomett sold to John Winthrop Junior.

Along the approach drive, I screeched to a halt to admire this jaw-dropping vista. In the foreground: One of the two Towers in the Vegetable Garden. The Vegetable Garden was designed by landscape architect Arthur Shurcliff, and built from 1917 to 1919. Farther down the slope are the buildings of the Farm Complex, which were designed by the architectural firm Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, and built from 1914 to 1916.

Further up the approach driveway, this was my view inland, toward the West, over an August tapestry of purple loosestrife, goldenrod and cattails, and a network of sinuous water channels.

On two of my three August visits, I brought along guests. Neither of my companions had ever been to Castle Hill, and I eagerly awaited their first impressions of the place. On August 16th, my nephew Leo Quick accompanied me, and on August 25th my design-colleague Holly Alderman rode shotgun.

This first glimpse of the Great House caused both to exclaim something on the order of “we’re not in New England anymore, “ to which I replied, “Nope….more like we’ve gotten to England Proper, somehow…”

Three other souls approached the Great House, during my first visit, on August 12th. The day was SO perfect that this absence of crowds surprised me. Castle Hill deserves to be seen: by all those who love gardens, interior design, architecture, and history!

Every inch of the Great House was carefully designed by architect David Adler. Per the Trustees: “Mr.Adler, a perfectionist for details, designed the ornamental cast-lead downspouts to echo the fruit and floral motifs” seen in the wood carvings done by Grinling Gibbons, which decorate the House’s Library.

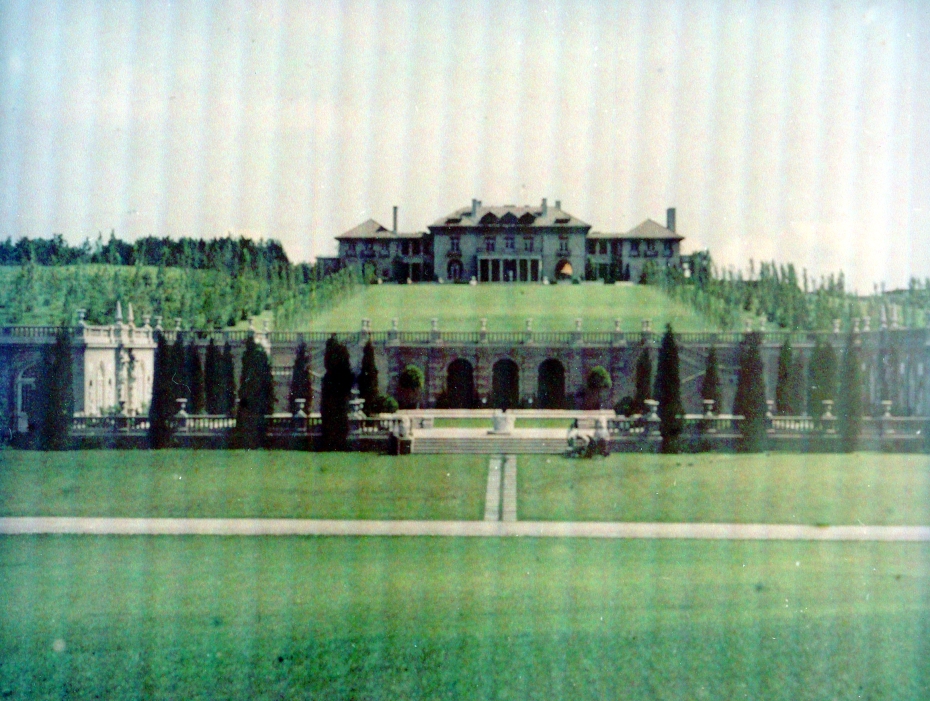

But wait! Before we pass through the front door and into the Great House, you may recall my mention of the local excitement generated by the HOUSES that Crane built. Yes, the English country manor that greets today’s visitors is the Crane-House, Beta-Edition. The Alpha-Edition, built in 1910, was, while equally grand, utterly different in character. In 1909, when Chicago industrialist Richard T. Crane Jr. decided that a couple thousand acres of Ipswich waterfront would be the perfect place for his family to linger during six weeks of every summer, he engaged Boston architects Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge to build him a villa, in the Italian style. A Renaissance Revival vision appeared, its 60-plus rooms enclosed within stuccoed walls, and sheltered under red-tiled roofs. Terraces and balustrades with complementary, Palladian lines were erected to surround the Great House. Similarly-styled outbuildings were designed—the most impressive of which formed the Casino Complex: with a Ballroom, Bachelor’s Quarters (single, male guests were NOT allowed to sleep in the main house), courtyard, and saltwater swimming pool.

Boston’s Olmsted Brothers were simultaneously engaged to plan gardens which would harmonize with the Italian Villa, and, in 1912, an Italian Formal Garden was completed, to the west of the House.

This is the southwest facing, front entry side of the Original Italian Villa, in 1912. Note the obelisks and entry drive balustrades, which are still intact, today. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

Northeast-facing, oceanside elevation of the Crane’s Original Italian Villa, in 1911, before landscaping to the rear of the House was done. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

Hand-colored photo of the oceanside elevation of the Original Italian Villa, as of 1915. The Grand Allee, designed by Arthur Shurcliff, has been installed. And the Casino Complex, designed by Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge, is in the foreground (tucked into a hillside slope). Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

When Richard T.Crane Jr. first brought his wife Florence, and their two young children, Cornelius and little Florence, to their new seaside abode, Florence Sr. declared an intense dislike for the building. After a couple of summers there, and still unable to mollify her, Richard promised his wife that if, after 10 MORE summers, she still loathed her Italian Villa (her claim that the building was cold and drafty seems strange, given the perfect climate of Ipswich in the summertime), he would duly tear down the offending house and begin again. Florence, with the persistence of a bulldog, prevailed, and in 1924, the Italian Villa was dismantled, right down to its foundations. Pilar Garro explained: “From what I understand, some of the building material debris was deposited on the property in an area called Cedar Point. “ And “some of the fixtures like sinks and tiles from the first house were made available to the community. A few Argilla Road neighbors have these items in their homes.”

My oh MY! WHO were these people who possessed enough sheer brass to knock down such a solidly-constructed and palatial house, or—more to the point—where did they get the money that allowed them to take such drastic actions? Granted, architectural misadventures among America’s very-rich were not unknown. As I reported in my Armchair Diary about Kykuit (John D. Rockefeller’s home), in 1908, after a six-year-long construction ordeal, the mansion that architects Delano and Aldrich had designed was deemed unsuitable by Mrs. Rockefeller. Ogden Codman Junior was then assigned the task of remodeling the unsatisfactory house. But even the Rockefellers had shown some restraint as they altered Kykuit: far from being a total knock-down, their home-improvements refashioned the existing rooms while interior bearing walls were maintained, and the exterior walls were extended and then camouflaged with new stone cladding. But now… back to those extravagant Cranes, who dismantled every timber and discarded every tile of their Italian Villa, as they cleared the deck for their new, English Country House. Actually, sheer brass had more than a little to do with R.T.Crane Junior’s ability to take such draconian measures…which leads us to this necessary pause for a history lesson.

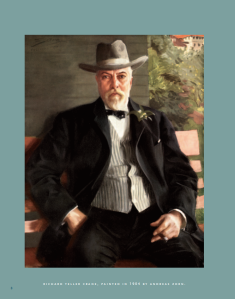

On July 4, 1855, 23-year-old Richard Teller Crane opened a little business in Chicago, which he named the R.T.Crane Brass & Bell Foundry. Crane, who’d been born poor, and in New Jersey, had gone west to make his fortune. Using wood salvaged from the lumber mill that an uncle owned, Crane set up shop in a 14 by 24 foot shack he himself had hammered together. That the rest of his life would unfold in Horatio-Alger-ish, rags-to-riches fashion, was beyond improbable.

Richard Teller Crane (born 1832, died 1912): founder of the Crane Company. This image of the portrait painted by Andreas Zorn is used, courtesy of CRANE: 150 YEARS TOGETHER, published by the Crane Company.

Following now are tidbits gleaned from The Crane Company’s extensive history of the origins and development of their business: CRANE–150 YEARS TOGETHER.

R.T.Crane’s Founder’s Statement. Image courtesy of CRANE: 150 YEARS TOGETHER, published by the Crane Company.

Using the skills he’d gained as a machinist in a foundry, Crane began by taking orders for castings of the metal containers which were used to hold the lubricating material that lessened axle friction on railroad cars. After being joined by his brother Charles, Richard Crane decided to expand their product line to include a wide array of brass goods that they’d manufacture: locomotive parts, wrought iron pipe, fittings, valves, and steam-warming equipment.

A gigantic Crane Company Valve. Image courtesy of CRANE: 150 YEARS TOGETHER published by the Crane Company.

The outbreak of the Civil War in 1861 proved to be another major turning point for the business, which was now named R.T.Crane & Brother. The U.S. government awarded large contracts for infantry and cavalry equipment to saddlery makers in Chicago, which required the Cranes to manufacture a wide variety of brass fittings. As the 1860s progressed, and the nation’s population grew, the company, now called the Northwest Manufacturing Company, developed an important new line of business with the fabrication and installation of steam-heating equipment in private homes. Diversification followed, as the Crane Elevator Company began making hoists, elevators and steam engines. By the 1870s, Richard Teller Crane had invented multi-purpose machines and conveyor systems for moving molds and pouring metal, which facilitated the birth of line production in foundries. Up until the moment he died in 1912, Richard Teller Crane had worked incessantly, and he’d trained his two sons—Charles Richard, his eldest; and Richard Teller Junior, his youngest—to succeed him.

Per the Crane Company History:

“ ‘It is my hope,’ R.T.Crane wrote to his sons in a letter that accompanied his will ‘that they will continue the work I have started.’ He urged his oldest son,

Charles Richard Crane, and his youngest, Richard Teller Crane Junior, to keep a firm grasp on the family’s far-flung and thriving industrial empire. Both sons, however, were eager to take control of the family business, and a controversy over the terms of their father’s will erupted between the two. The firstborn, Charles, believed it was his natural right of succession to take over the leadership of the Company, while R.T.Crane Junior believed he was better able to manage it.”

“Although the Crane brothers had succeeded in building one of the most modern factories in the U.S” which was known as the Great Works…

The Great Works, built by the sons of Founder Robert Teller Crane. This gargantuan complex–completed in 1912–and built upon 160 acres in Chicago–was the most modern factory of its time. Image courtesy of CRANE: 150 YEARS TOGETHER, published by the Crane Company.

“…controversy over their father’s will continued to split the two apart. To settle the matter, their lawyers asked them to submit a closed bid to each other that named a price for buying the other out of the family business. R.T.Junior made the higher bid, Charles accepted it, and agreed to step down in the summer of 1914.”

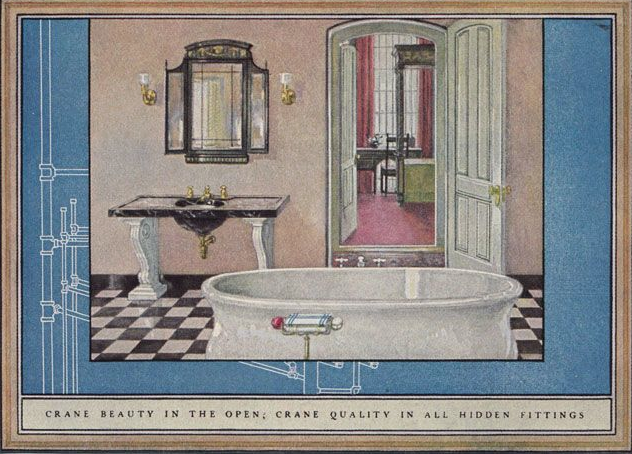

That the name of CRANE became known to most Americans can be attributed to R.T.Crane Junior, who “pioneered his Company into a promising new direction during the 1920s, “ as he made homeowners desirous of more luxurious bathrooms. “With their factories at Trenton, NJ, and Chattanooga, TN, the Crane Company began manufacturing their own line of ‘sanitary ware.’ Designers were brought in to create custom-made, colorful, innovative, and distinctive bathroom ensembles that were completely different from the drab, uniformly-designed models currently on the market. There was only one thing missing: demand. But R.T.Crane Junior believed that the Company could create a demand for the new, luxury bathroom through an aggressive, national advertising campaign. “ Because of those campaigns, the manner in which products were thereafter marketed in America was revolutionized. And until the 1970s (when The Crane Company got out of the “sanitary ware” business), the CRANE logo appeared upon the bathroom fixtures of many well-appointed American homes.

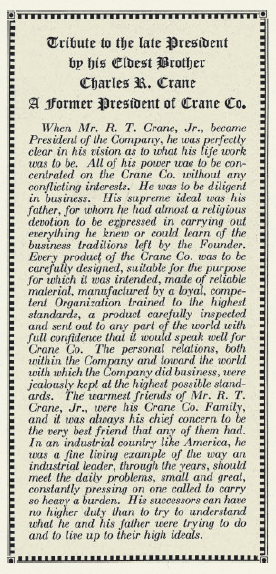

Richard Teller Crane Junior worked hard, so hard that he exhausted himself into a early grave. He died in 1931, on his 58th birthday, and was much mourned by the Company he’d nurtured and expanded. Upon his death, his eldest brother Charles, over whom he’d once prevailed, published this tribute:

Charles Crane’s tribute to his brother. Image courtesy of CRANE: 150 YEARS TOGETHER, published by the Crane Company.

R.T. Junior was a creative thinker, a skilled engineer, and a fiercely devoted boss and father-figure to his thousands of employees. This son was clearly a worthy successor to his father.

Only after one learns about the ambitions and achievements of R.T.Crane Junior can one make sense of the intense manner in which he approached the creation, and then the re-creation, of his vacation retreat at Castle Hill. This was a man who instinctively synthesized information, and did nothing in half-measures. His home, like his businesses, had to reflect the best: of engineering, and of design. And so Florence’s plea that her husband give her a summer house that she could love—however wasteful destroying the unwanted Italian Villa might be—became just one more challenge in R.T. Junior’s eventful life. Remember, this was a man who had overseen the construction of an innovative factory complex which covered 160 acres; merely replacing one manor house could hardly be daunting, compared to the magnitude and complexity of expanding the Crane-industrial-empire.

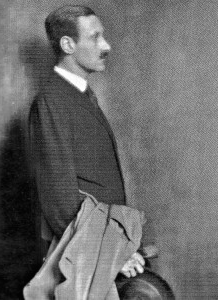

This photo of Richard Teller Crane Junior is displayed in his bedroom, on the second floor of the Great House. Crane was born in 1873, and died in 1931. He had very few years to enjoy his second Great House, which was completed in 1928.

Now, history detour over, our tour of the Crane Estate can begin:

Every visit to Castle Hill ought to start with a guided tour of the Great House.

Tours are given seasonally, so visitors should check with the Crane Estate beforehand, for details about open days, and tour times. [Note: Crane Estate contact information is listed at the conclusion of this Diary.]

For their second attempt at summer-home-making, the Cranes hired Chicago architect David Adler.

Architect David Adler (born 1882, died 1949). Over the course of his 35-year-long career, Adler designed more than 200 buildings, many of which were in the Chicago area, but the Great House of the Crane Estate, at Castle Hill, is his most famous creation.

Per the Trustees of Reservations’ design notes about the Great House, Adler’s “eclectic sense of design drew from different architectural styles, and for the Crane’s Ipswich residence we see the inspirations of 17th century English country houses, 18th century Georgian interior woodwork, Baroque carvings, Gothic-style vaulting and even an Art Deco feel to the bathrooms.”

Much of the interior woodwork in the Great House came from grand English homes that were being dismantled… then to be sold to the highest bidder.

Continuing with the Trustees’ notes: “With carefully achieved symmetry throughout, Adler refitted, on both floors, interior woodwork removed from an 18th century London townhouse [Note: the townhouse was located at 75 Dean Street, Soho, but demolished in 1921] which Mr.Crane purchased through W.& J. Sloane in New York. Also on the first floor is the library, which was purchased in part from Cassiobury Park, Hertfordshire, England.”

This was Cassiobury Park, in Hertfordshire, England. The House was begun in 1546, and, over the years, extensive additions followed. In 1927, the entire structure was demolished (OUCH!). Cassiobury Park’s destruction was fortunately-timed: Richard T.Crane Jr. acquired many of its most precious interior decorations, which Richard Adler then installed at Castle Hill’s Great House. Cassiobury Park’s most valuable elements, the decorative woodcarvings by Grinling Gibbons, now decorate the Library of the Crane House.

To my eyes, one of the impressive aspects of the interiors of the Crane home is the graceful way in which Adler reused what had to have been ship-loads of superb and sometimes irreplaceable pieces of British woodcarving and paneling and stonework. In none of the Great House’s rooms do those decorative elements feel as if they’ve been tacked on, or forcibly squeezed into place. Instead, all of the antique ornamentation melds seamlessly with Adler’s architecture. As we inspect the most significant areas of the 59-room home that Adler designed for the Crane family, you’ll see that, despite its grandeur, the house is actually quite welcoming and comfortable, something my nephew Leo Quick immediately sensed: upon entering Mrs. Florence Crane’s bedroom, he grinned and exclaimed, “this room is COZY!”

The exterior elevations of Adler’s Great House also reference English country homes. The cupola which dominates the roofline of the house is a replica of the cupola at Belton House, in Lincolnshire, England….

Belton House, in Lincolnshire, England, is one of the finest examples of the Restoration, or Carolean, style of architecture, which flowered from 1660 until 1680.

The Cupola, at the Crane’s Great House in Ipswich, Massachusetts: a copy of the cupola at Belton House.

Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations.

…and for the ocean-facing elevation of the Crane’s house, with its two protruding wings, terrace, and double loggias, Adler took his design-cues from the façade at Ham House, in Surrey, England.

Inside and out, Adler’s masterfully-disciplined demonstrations of material- recycling and architectural-homage stand surely on their own, two design-feet; never does his work devolve into pastiche.

Time now to enter the Great House:

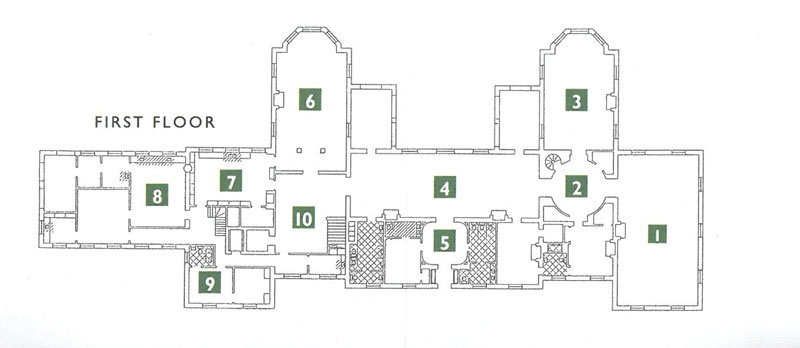

The FIRST FLOOR ROOMS. 1-Living Room. 2-Rotunda. 3-Library. 4-Gallery. 5-Reception Foyer. 6-Dining Room. 7-Butler’s Pantry. 8-Kitchen. 9-Butler’s Suite. 10-Stair Hall.

Vintage photo of the Foyer, as it looked from 1928 until 1949. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

This area, to the right of the Reception Foyer, is now the Ladies Bathroom. When the Cranes lived here, these rooms served as the mens’ dressing room. The walls are paneled with English deal (which is a soft wood similar to pine).

The Gallery connects the east and west wings of the Great House. This space is 63 feet long, with a 16-foot ceiling. A bank of windows in the Gallery overlooks the back terrace, and the half-mile-long Grand Allee, which extends to the Atlantic Ocean. In this view, we’re looking toward the east wing of the House, which holds the Rotunda, Living Room, and Library

Two imposing fireplaces are centered on interior walls of The Gallery. One fireplace is crowned by a large clock.

Detail of The Gallery’s Clock. Chicago artist Abram Poole painted the four winds which encircle the clock.

The other fireplace in The Gallery is topped by a large wind indicator. Mr.Crane and his two children were avid sailors. When the indicators showed Good Winds Blowing, the Cranes would drop everything and rush to their sailboats. There are a total of 5 wind indicators installed in the Great House, all of which were formerly connected to a weather vane atop the Cupola.

The Gallery, looking toward the Great House’s Stair Hall, and the Dining Room wing. New curtains duplicate the look of the English chintz that Mrs.Crane had hung here, and the parquet flooring has been refurbished.

The dimly-illuminated Rotunda: which is entered from the east end of The Gallery. The Rotunda is a circular hallway which leads to the Library, former Guest quarters (not open to the Public), and also to the Living Room (a space that’s now used as a Ballroom).

Vintage photo of the Rotunda, as it looked from 1928 until 1949. The Gallery can be glimpsed though the doorway. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The ceiling and walls in the Rotunda were painted by Abram Poole, whose inspiration for the decoration of this space was the Camera degli Sposi—in the Palazzo Ducale, at Mantua, Italy—which was painted by Andrea Mantegna, in 1470.

This is what inspired Abram Poole: Andrea Mantegna’s peerless ceiling painting, at the palace of the D’Este family, in Mantua, Italy. I visited this exquisite room in November of 2002, and this humorous. and luminously painted bit of Trompe L’oeil made a huge impression upon me.

Per the Trustees’ design notes about the Crane House: “As an affectionate reference to Mantegna’s work, many of Poole’s details are directly alike, as well as the mural’s overall effect of a classical pavilion. The oculus is faithful in concept, geometry and perspective, but the figures here are members of the Crane family and staff, along with their Siamese cat. Poole continues to reference Mantegna by including a peacock: a traditional symbol for Juno, the goddess who presides over marriage and childbirth. The mural is executed in oil on canvas, which has been glued to a gesso wall preparation. A light surface cleaning was completed in Apirl 1997. The mural colors remain dark due to the tinted original varnish, giving it an intentionally aged appearance.”

Having once had the great privilege standing nose-close to Mantegna’s murals in Mantua, I must say that Poole’s paintings suffer in comparison. Poole’s efforts are those of a raw student, as he strives to emulate a Master. On August 16th, when Leo and I joined a small group tour of the Great House, none of our fellow visitors had ever heard of Mantegna. Thus, the features of the Rotunda serve dual purposes: they reveal the Cranes’ desire to be recognized as knowledgeable about cultural touchstones of the Western World; and, more importantly, they might induce Americans who’ve never been to Italy to begin to investigate the works of Andrea Mantegna.

This was the Crane’s Living Room, and is today used as a Ballroom. The Living Room has windows on three sides: facing south, east, and north. French doors on the east wall lead to a terrace overlooking a lawn, which was once a grass tennis court, and later, a bowling green. Below the bowling green was an arbor, and then, on a still-lower terrace, a hedge maze.

The Living Room’s fireplace. Per the Trustees, after Mrs.Crane’s death in 1949, the entire contents of the Great House “were sold at auction by Parke-Bernet, held on-site over the course of three days.” As the Trustees now restore the interiors at the Crane Estate, paintings and furnishings which resemble the originals used by the Cranes are being installed.

Painting over fireplace, with a closer look at the paneled walls. Per the Trustees, the Living Room has recently been restored “to its original color scheme, which combines sand-colored walls with glaze-painted moldings.”

Detail of fireplace surround, in the Living Room. Happily, during the Parke-Bernet auction, only the family’s furniture and works of art were sold. Many decorative features affixed to the walls have remained intact.

If only one room of the Great House had to be preserved for posterity, that room would certainly be the Library, by virtue of its decorative wood carvings, which were done in the 1670s by the English Baroque sculptor Grinling Gibbons.

The Library, as we see it today. The elaborate carvings over the fireplace are by Grinling Gibbons, and were obtained from the English country house called Cassiobury Park, when Cassiobury was demolished in 1922. All furnishings and books have been chosen by the Trustees to resemble the furnishings used by the Crane family. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations.

Vintage photo of the Library, as it looked from 1928 until 1949. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Vintage photo of the Library’s bay window, which overlooks the Grand Allee. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Grinling Gibbons (born 1648, died 1721). Gibbons was a Dutch-British sculptor and wood-carver whose work decorated St.Paul’s Cathedral, Windsor Castle, Blenheim Palace, Trinity College Chapel at Oxford, and Hampton Court Palace (and that’s just the beginning of the List….)

Let’s take a closer look at the Gibbons carvings in the Library. Per the Trustees, the Crane Library’s “overmantle carving is one of Gibbons’ earliest surviving decorative works. It is one of only two known documented sources of Gibbons’ work [in America]. He is known especially for his high-relief, delicately carved limewood festoons of accurately rendered flowers, leaves and fruit. These limewood carvings were originally bone white in color, giving a cameo-like appearance against the darker ground. However, in keeping with Victorian fashion, these carvings were darkened with varnish in the 19th century.”

Grinling Gibbons’ carvings crown—and rather outshine—a portrait of Lady Emma Anderton (which is actually OK, since Emma was simply a purchased portrait, and not a relative of the Crane family). This just goes to show, however, that even a beautiful lady cannot complete with Gibbons’ artistry.

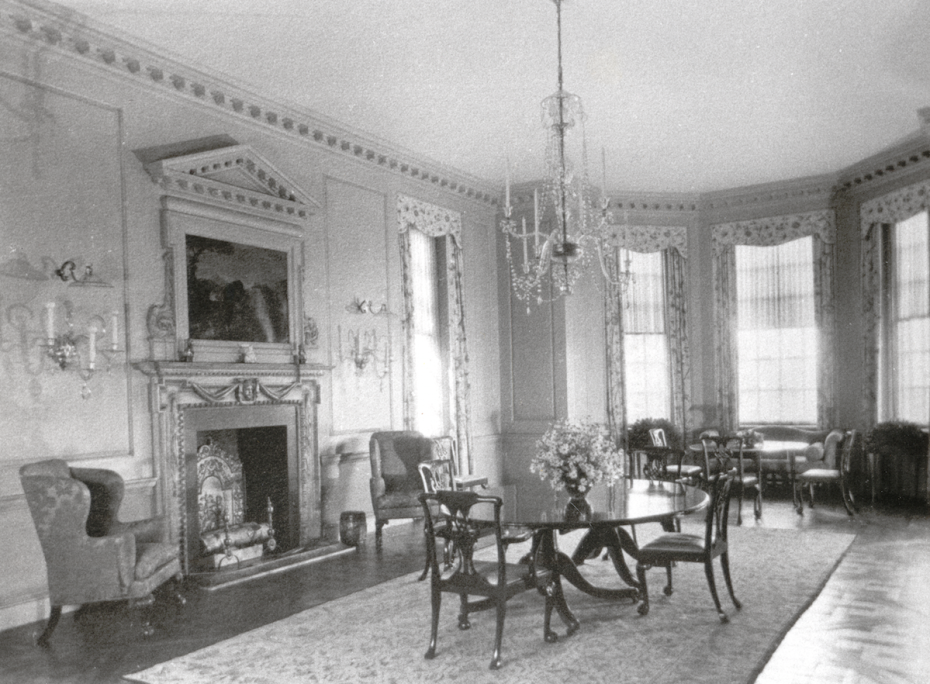

We’ll next walk the length of the The Gallery, toward the western end of the Great House. Our first stop: the Dining Room. The Dining Room, like the Living Room, is kept largely empty, so as accommodate the weddings and other events which are regularly held at the Castle Hill.

My first glimpse of the Dining Room, as seen from the Great House Stair Hall. David Adler divided this long, slender space “with a pair of free-standing fluted columns, which were flanked by a pair of engaged columns, all with Ionic capitals.”

Once inside the main area of the Dining Room, I became more aware of the delicate hues of the House’s color schemes. So that her new, improved summer home would feel in harmony with its beautiful setting, Mrs. Crane and David Adler worked out a disciplined decorative palette. Every unpaneled wall in the house is painted or glazed in custom-mixed colors: with blues, tans, creams, greens, or yellows. Because of these gentle, natural colors, which mimic the colors of the landscape outside, the Great House never seems stiff, or overwhelming, despite the opulence of its detailing.

Vintage photo of the Dining Room, as it looked from 1928 until 1949. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

Vintage photo of the Dining Room, with a glimpse of the Stair Hall. Behind the folding screen to the right is the entrance to the Butler’s Pantry. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

The marble mantle is based on a design by 17th century English architect Inigo Jones (born 1573, died 1652). Inigo Jones is most renowned for his design of the Queen’s House, at Greenwich (which I wrote about and photographed for my Diary entitled “The Great Canopy of London’s Skies; Getting Older in Greenwich”)

Detail of Dining Room, with boldly dentated moldings, and a closer look at the paint color and glaze work. Per the Trustees: “Careful paint analysis performed in 1997 revealed the monochromatic blueish-green base with a darker green glaze work. Further analysis in 2008 revealed a touch of blue to the light ceiling. The room was glazed from top to bottom in 2008 by Phyllis Tracy of Marblehead, MA.”

In the Butler’s Pantry, a visitor sees what the Trustees describe as “the first glimpse of the vast support network required to run this summer home.” During each of the Cranes’ summer stays, up to 100 Ipswich residents were hired to run the Great House, and its vast gardens.

Per the Trustees, the Butler’s Pantry was “an interim serving station for the dining room, complete with a warming cupboard within the central stainless steel table. Serving staff could receive plates from the revolving cupboard connected to the kitchen. A tier of cabinets surrounds the room, while another tier, for storage of fine china, is located on the mezzanine above.”

Detail of cupboard doors in Butler’s Pantry. The room has been restored to its original color scheme of off-white and deep blue. Ever clever and practical, Adler had these blue diamonds painted around each cupboard knob to hide the smudges left by the food-stained hands of kitchen workers.

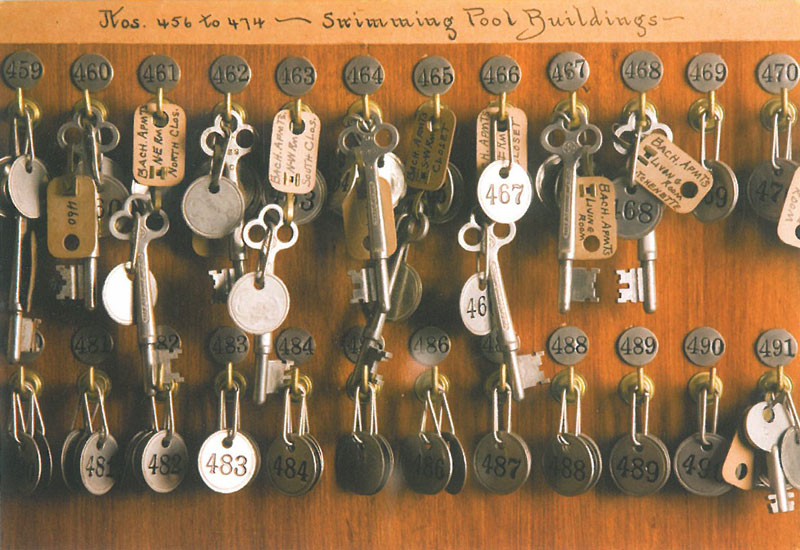

Close to the Butler’s Pantry is the Butler’s Suite, which consists of a small office/sitting room, bathroom and bedroom. Smooth Sailing at Castle Hill depended less upon those wind indicators, and more upon the Butler, who kept an eye on all comings-and-goings, and, more importantly, HELD THE KEYS.

In the Butler’s Suite is a double-layered Key Cabinet, which held over 200 numbered and labeled keys.

On another wall in the Butler’s sitting room are numbered floor plans, which correspond to the house keys. Egad…this Butler’s life was NOT simple.

The Butler got an UN-fancy bathroom. Remember these Plain-Crane-Fixtures (which look like most of the fixtures we all saw, way-back-when) once we get upstairs, and inside of the Crane family’s private

Bathing-Heavens.

This corridor leads from the Butler’s Suite toward a Flower Room (straight ahead), and also back to the Great House Stair Hall (door to the left).

Leaving the nuts-and-bolts rooms of the Great House, we return to the public spaces, and enter the Great House’s Stair Hall. More now, from the Trustees’

notes about the Crane home:

“The stair hall outside the Dining Room is modeled after one from an 18th century London townhouse. The house, at 75 Dean Street in Soho, was demolished (circa 1921) and its grand wood-paneled interiors were being sold by New York department store W&J Sloane. Upon Adler’s recommendation, Mr. Crane purchased these interior fittings for his new mansion at Castle Hill. They have been divided up and used here among seven bedrooms, the dining room and the upstairs sitting room. These period rooms fit in with Mr.Adler’s

English country house design scheme and served as an elegant setting for the Cranes’ growing collection of 18th century English and American furnishings.”

“The original circa-1732 painted oak and pine staircase did not fit the larger scale of the Adler house, so this reproduction [of the Soho townhouse’s staircase] was made incorporating all the same intricate carvings, twisted shafts and Corinthian column newels at each landing. In turn, the original London ‘Grand Staircase,’ and other unused townhouse rooms were donated to the Art Institute of Chicago by Mr.Crane in 1925. As museum items, these attest to the high quality of woodwork installed in fashionable early 18th century houses in London’s Soho district.”

“Great efforts have been made [by the Trustees] in recent years to restore this area of the house. Paint colors and glaze treatments have been restored; furnishings have been purchased or reproduced to scale; and fabric colors reintroduced. The chandelier is original to the space, as are the Regency sconces with eagles on the second floor landing.”

Vintage photo of the Stair Hall, as it looked from 1928 until 1949. Image courtesy of the Massachusetts Historical Society.

View of the Stair Hall, from just inside the Dining Room. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations.

Etched brass doorknob plate, on the door in the Stair Hall which leads to a first-floor, walk-in Safe. When the Cranes decamped after each summer visit, their sterling silver, and most valuable paintings, were locked away.

Near to the Safe’s door in the Stair Hall, a small wind indicator is installed. A good wind blowing was the Crane-Family-Equivalent of SURF’S UP!

…and crane our necks (of course we Crane) for a better look at the Stair Hall’s chandelier, which is original to the House.

On the second floor landing, we consult this Room Plan:

The Second Floor rooms of the Great House. 11-Son Cornelius’ bedroom suite. 12-Oak Guest Room. 13-Apricot Guest Room. 14-Chinese Guest Room. 15-Second Floor’s Main Hallway. 16-Mrs.Florence Crane’s bedroom suite. 17-Family Sitting Room. 18-Mr.Richard T. Crane Junior’s bedroom. 19-Daughter Florence Crane’s bedroom suite.

The Trustees comment thusly about the enormously long, second floor Hallway: “It is worth noting again David Adler’s eclectic sense of design, incorporating Gothic-style vaulted ceilings with Greek Revival lighting fixtures and Adamesque neo-classical fan lights above the double doors, which are typical of the Georgian era in England and the Federal period in America.”

My view from the opposite end of the main hallway, as I stood by the door which leads to the Chinese Guest Room (to the right). and the entry to Mrs.Crane’s suite (to the left).

Halfway along the second floor’s main hallway is a large, light-filled sitting room, which overlooks the Grand Allee, and the Atlantic Ocean. This portrait of the Crane children is currently hung here. The painting was done is 1914, by Lydia Field Emmet, who maintained studios in New York City, and in Stockbridge, MA.

Detail of Lydia Field Emmet’s portrait of Cornelius and Florence Crane…who were indeed very pretty children.

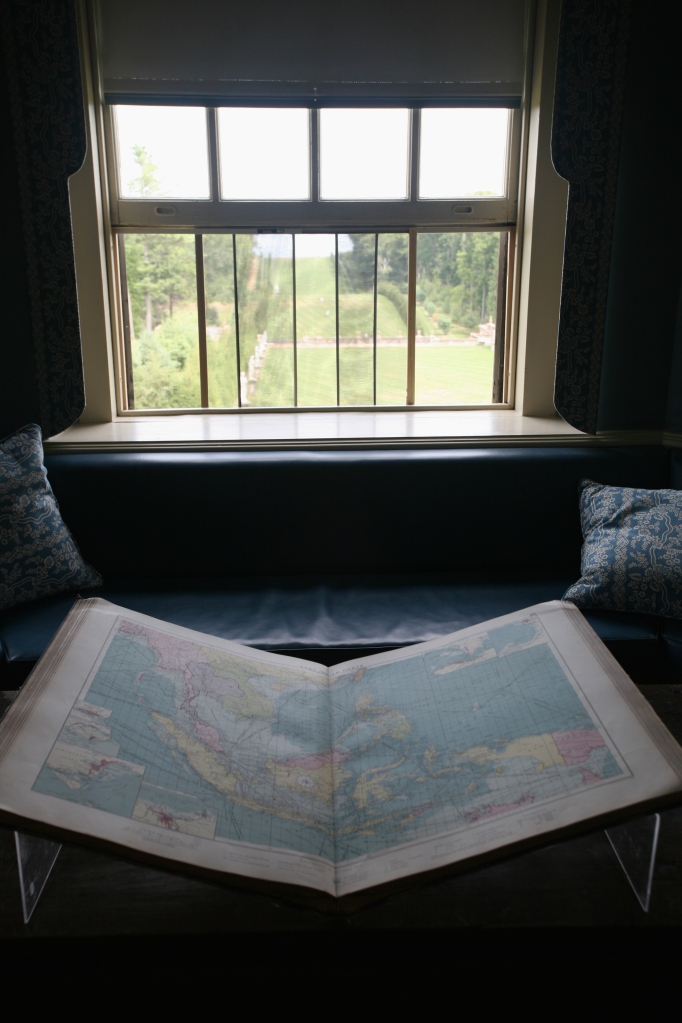

View from the second floor hallway’s sitting area. The Grand Allee stretches for a half mile, down to the Atlantic Ocean.

We’ll first take a look at the three Guest Bedrooms on the second floor, which the Trustees’ design notes introduce: “A series a guest rooms were named for the decoration at the time. These names are noted on keys that lived in the Butler’s key cabinet downstairs. All guest rooms have en suite bathrooms with silver-plated fixtures and, of course, period Crane plumbing fixtures, which reveal the Art Deco style. Creature comforts such as bathrooms, and overstuffed club chairs and sofas were among the few modern features of the house.”

The Apricot Guest Room is not open to visitors taking tours of the Great House. But when the Crane Estate is rented out to wedding parties, this room is used as the “Bride’s Room.”

The Apricot Guest Room’s bathroom. One look at the space, and I was in LOVE. The apricot-hued, book-matched marble! The silver-plated fixtures! The original green and silver Chinese wallpaper! As a connoisseur of bath-taking, I was ready to strip down and fill that tub!

The marble sink counter in the Apricot Guest Room’s bathroom. This room, which faces southwest, has

abundant, natural light.

Across the main hallway from the Apricot Room is this darker, more masculine space: The Oak Guest Room. The Oak Room is paneled with wood from the late 17th century. The stepped shelves over the fireplace once held Staffordshire ceramic figures. The bathroom’s walls were originally covered in silver tea paper.

Across the main hallway from the door to Mrs. Crane’s dressing room is the Chinese Guest Room. The Chinese Room’s fireplace has an ornamental 18th century mantle from the dismantled Soho townhouse.

The Chinese Guest Room’s walls were originally covered with hand-painted Chinese wallpaper, but those wall coverings were sold at auction, after Mrs. Crane’s death. The room has been redecorated with fabric that’s in the same style as the original, far more precious wall coverings.

Now, on to the bedrooms of the Crane family. We’ll begin with son Cornelius’ suite, which is at the top of the Great Hall Stairs. By the time the second version of the Great House was constructed, Cornelius was a young man of 23 years old. David Adler gave him a measure of privacy and independence, by locating Cornelius’ rooms apart from those of his sister, and parents, which were placed at the opposite end of the long, second floor hallway. And within the short hallway which serves as the entry to Cornelius’ domain, there’s also a small staircase which leads to the loft-like third floor (which was known as the Billiard Room, or the Chart Room…where the Cranes’ collection of nautical charts were shelved) of the Great House, and further, to a steep, spiral staircase which then leads up through the Cupola, and onto a roof deck, where 360 degree views of the entire estate can be had. We’ll pop up to the roof deck first, to enjoy the same vistas that Cornelius and his visitors enjoyed.

Sadly -–but sensibly, from a safety standpoint– the roof deck isn’t open to folks who take Great House tours. Fortunately, during my first visit to Castle Hill, Pilar Garro DID guide me up to the Great House’s wonderful aerie…

Cornelius and his sister Florence, sitting on the Cupola’s steps, in the early 1930s. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

As Pilar and I basked in the sunshine, and enjoyed the views from the Roof Deck, we saw Kristi Perry leading two reporters from DESIGN NEW ENGLAND magazine across the upper lawn.

It’s always such a Small World, isn’t it? To see DESIGN NEW ENGLAND’S article about my own, vastly less-grand home in New Hampshire, see their May/June 2009 issue. Here’s the link:

https://digital.designnewengland.com/designnewengland/20090506?pg=96&search_term=nan%20quick&doc_id=-1&search_term=nan%20quick#pg96

My August 12th view from the Roof Deck, toward the northeast: to Ipswich Harbor (on the left), and out to the Atlantic Ocean.

Because the Crane family lived in Ipswich for only 6 weeks of every summer, Cornelius had little opportunity to meet local playmates. His father solved that problem with a typical, grand, Crane-ian flourish. He invited ALL of the elementary and middle-school children in Ipswich to celebrate Cornelius’ June 29th birthday with him. Even after Cornelius outgrew the need for such parent-arranged play-dates, the Crane Beach Summer Picnic continued. Thanks to the generous trust fund left to the Town of Ipswich by Richard T.Crane, Jr., the annual Crane Beach Picnic has now been held for over 100 years.

Vintage photo of the Crane Beach Picnic, circa 1911. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations.

View inland from the Roof Deck, toward the southwest. A portion of the front entry court is directly below.

View inland, toward the northwest, with the entry court directly below, and the parking lawn in the distance.

Pilar and I then carefully made our way down the spiral staircase, and entered the suite of rooms that Cornelius occupied as a young man. The Trustees provide these background notes: “Cornelius Crane (1905—1962), named after Mr.Crane’s friend Cornelius Vanderbilt, was a great lover of the sea. In 1928-1929, he set out on an anthropological expedition to the South Seas with a team of scientists from Chicago’s Field Museum of Natural History, and his friend Sidney Shurcliff (son of landscape architect and Agilla Road neighbor Arthur Shurcliff). His yacht, built for this adventure, was a 148-foot steel auxiliary brigantine named the ILLYRIA. They followed the trail of Darwin and Wallace, venturing from the American tropics though the Panama Canal to the Galapagos, New Guinea, Borneo and other islands in the South Pacific. Sidney Shurcliff documented the trip with films and his book JUNGLE ISLANDS.”

And of course, no proper adventurer can set to sea without also outfitting his ship’s mess with custom-designed China! Nope…the Cranes never roughed it.

Per the Trustees’ design notes about his bedroom: “Paint analysis revealed the sky/sea/sand color scheme from the ceiling down, which may have been inspired by just looking out the window. Adler’s penchant for blues and greens is evident throughout the house, with Cornelius’ room displaying the richest blued. The blue-leather tub chair and the desk are original to the room.”

At one end of Cornelius’ tub is a shower stall. Only the men of the household had shower stalls built into their bathrooms. The ladies of the house had no showers, and had to make do with tub-soaks. Discuss….

Even the underside of Cornelius’ sink is beautiful. Yes, at this point I’d thrown all dignity to the winds, as I crawled on the floor, to do my photo-taking. Pilar didn’t seem to mind….

Fixtures on Cornelius’ tub.

Just rest your eyes upon this loveliness, and dream of taking a bubble bath…

Onward now, to Miss Florence Crane’s bedroom suite. Again, the Trustees’ design notes set the stage: “Like Cornelius, Florence Crane (1909—1969) had a breathtaking view down the Allee to the sea, a sleeping porch connecting bedroom and bath, and a separate dressing area with built-in closets. Her bathroom is covered with eglomise (reverse-painted glass) tiles depicting silver ships at sea, and the door handles of this suite are cobalt-blue glass.”

Florence’s very narrow bathtub. Just looking at the slender width of this makes me feel grossly overweight…

Florence Crane’s bedroom is being restored. Per the Trustees: “Paint analysis showed this taupe on taupe glazed finish, a complicated treatment on the ornamental woodwork. It has been replicated, giving the room a serene color scheme. Florence, who was nearly 20 when this home was completed, had a room that reflected more of a 1920s Hollywood Deco style with its elaborate sky-blue swags and sheer draperies. Restoration efforts are currently underway on this room. We recently installed the elaborately styled blue poplin draperies, as per the 1931 photo documentation. We plan to raise the bed canopy in order to complete the bed hangings in the same fabric and to the right scale.”

Florence Crane’s first marriage, to William Robinson, produced one son, and ended in divorce. Florence’s second try at matrimony was more successful: in 1943 she wed White Russian Prince Serge Belosselsky-Belozersky, and they had two daughters, both of whom maintain homes in Ipswich. Oh, by the way:

Florence’s brother Cornelius also married twice. His first try didn’t work, but his second marriage, to Japanese artist Mine Crane, was very happy.

The Trustees explain: Florence’s “privately printed, limited edition book, IMPRESSIONS OF FOREIGN LANDS, was published in 1927 and captures the journal entries of her 6-month travel through Europe and North Africa to the Middle East to Greece and back to Europe.”

Richard T. Crane Jr.’s bedroom is adjacent to Miss Florence’s. Mr. and Mrs. Crane’s affection for their children is obvious: instead of building themselves the most spacious bedroom suites, the parents gave the largest accommodations over to Cornelius and little Florence. Each child had an entire wing of the house, which contained a series of rooms with outside exposures on three sides; their summers at Castle Hill were clearly meant to be all about enjoying fresh ocean breezes, and drop dead views. Compared to his children’s lairs, their father’s bedroom, which is paneled in dark wood from the Soho townhouse in London, almost seems austere.

Fireplace in Mr. Crane’s bedroom. Both the wall paneling, and the marble fireplace surround, came from the dismantled 18th century London townhouse.

On the north wall of Mr. Crane’s bedroom: an original 1926 paper silhouette portrait of his family–pets and all–made by Evelyn Maydell. This is completely charming!

Despite the restraint of his bedroom decor, Mr. Crane DID indulge himself, when it came to outfitting his bathroom:

Mr. Crane’s state-of-the-art, multiple-nozzle shower stall. An equal number of nozzles are on the opposite wall. All this needs now is a good scrubbing….

A rather jittery marble pattern on the walls of Mr. Crane’s bathroom….NOT relaxing (but perhaps never truly relaxing was the key to his productivity?).

A small hallway connects Mr. Crane’s bedroom with his family’s private sitting room, which is situated on the southeast corner of the Great House. Having been born in Chicago, and thus ever-mindful of the perils of fire (he was weaned on tales of Chicago’s Great Fire), Mr. Crane installed a fire hose in a closet, just outside his bedroom door.

The second floor sitting room allowed the Cranes to escape into the farthest, most-private corner of their house. Sometimes, with 100 servants and groundskeepers swarming over the property, the Cranes needed a room where they could hide for a spell.

The Trustees describe the Sitting Room as an “English-style room which boasts the most elaborate woodwork from the London townhouse. Great efforts have been made to restore this room to its original appearance. Draperies are made from the same fabric pattern and colorway that was originally used in this room, which is a 1924 Hollyhock pattern by English firm Lee Jofa. A 1949 inventory revealed to us that the sofa was blue, the wing chair yellow, and the bench green damask. Some original pieces are currently on loan in this room (mahogany armchair, side tables, andirons), and a very close match to the original English chest on chest was recently purchased for the room. The floral still-life and portrait paintings were also reframed to match the style of original frames in the room. The taupe carpet is original to the room.”

This is the view from the private sitting room, out to the east lawn. Below the lawn is the former site of a bowling green. And, on a still-lower terrace, an extensive hedge-maze was once planted. In the distance is beautiful Crane Beach, where I spent quite a few happy childhood weekends, getting sunburned.

Vintage photo of the Hedge Maze, with Pergola in the foreground, circa 1920s. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

And last but not least, we visit Mrs. Florence Crane’s suite, with its dressing room, bedroom, and—Taa-Daa— bathroom, which is my favorite space in her 59-room summer home. Yes, I have a THING about bathrooms, which makes the Crane manse a place of particular interest to me.

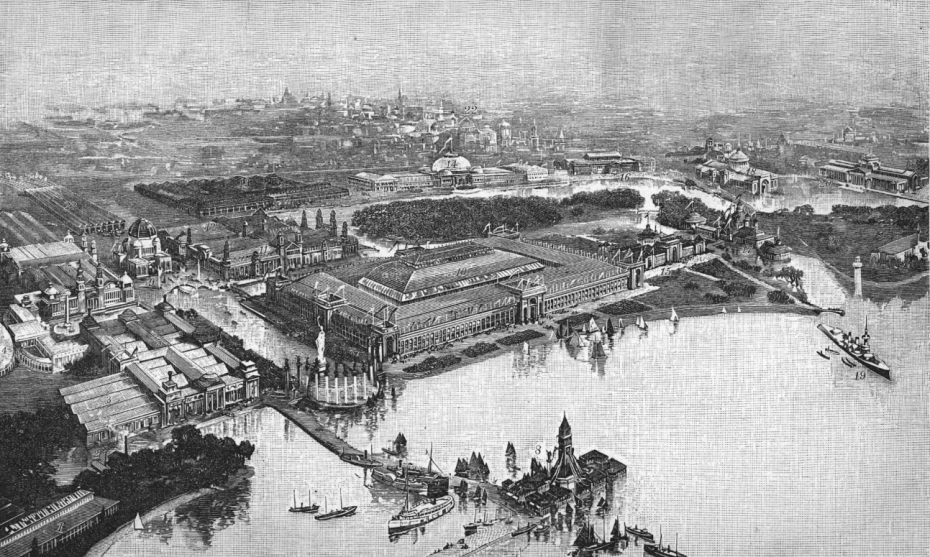

As the Trustees recount, “Mrs. Crane, born Florence Higinbotham, was from a prominent Chicago family. Her father, Harlow Niles Higinbotham, was a founding partner of Marshall Field & Co. and the president of the World’s Columbian Exposition of 1892-93.” Mrs. Crane was thus no stranger to grandeur; after all, how could a girl whose father had overseen such a spectacle as the World’s Columbian Exposition NOT have become accustomed to being pampered by positively EXOTIC surroundings?

Mrs. Florence Crane’s father was the President of the World’s Columbian Exposition, which was held in Chicago from 1892–1893.

And so the great surprise upon entering Mrs. Crane’s suite is seeing its modest size, and its sophisticated and nearly-spare decoration. To afford her a degree of privacy, Mrs. Crane’s sleeping area is separated from the second floor hallway by a small dressing room.

The Dressing Room opens on one side to Mrs. Crane’s bedroom: the space that my nephew Leo rightly called “Cozy!” More now, from the Trustees’ design notes: “The English deal (pine) paneling for Mrs.Crane’s bedroom is from the [18th century] London townhouse, and appears to have been glaze-painted to give a ‘pickled pine’ effect. English antiques and crewelwork-on-ivory fabrics originally graced the room. The table next to the bed is original; above which is an oval-framed portrait of the young Mrs. Crane. In the room is also a charcoal of Mrs. Crane done in 1919 by John Singer Sargent.”

This vintage photo of Mrs. Crane’s bedroom, as it appeared from 1928 until 1949, is displayed on an easel.

Detail of the very plain (but antique) door that separates Mrs. Crane’s bedroom from the main second floor hallway.

In Mrs. Crane’s bedroom: looking back toward the door that leads to her dressing room, and then to the bathroom, which is on the opposite side of the dressing room.

Now, onward to Mrs. Crane’s jewel-like private bath, which the Trustees’ design notes describe: this “elegant bathroom features a green marble tub area with matching faux-marble-painted woodwork and a patterned green-marble tiled floor. This is one room in the house where David Adler’s sister, noted interior designer Frances Elkins, may have had an influence, as it reflects some of her French, Art Deco-inspired style. Again we see eye-catching patterns at work. The original silver sconces remain on the walls.”

Architect David Adler had an equally-talented sister. Frances Adler Elkins, who achieved great fame as an interior designer, may very well have influenced her brother’s design of Mrs. Crane’s bathroom at Castle Hill.

On August 12th, I stood in the doorway to her dressing room as I photographed Mrs. Crane’s bathroom, which is modestly-scaled and Perfect-Beyond-Perfect! Her toilet cubicle is discreetly placed behind the right-hand door.

On August 25th, I returned to take more photos of Mrs. Crane’s bathroom. Per usual, my photo-taking involved a bit of floor-crawling.

Whereas the bedrooms of Mr. Crane, and their two children, were equipped with wind indicators, Mrs. Crane’s life was not attuned to sailing conditions, and so no wind indicator was wired into her personal space. Instead, all of her rooms, with windows that overlook the front entry court, allowed Mrs. Crane to keep tabs on visitors’ comings and goings.

…and here I am again, sprawled out on the floor, as I photograph the lovely underside of the sink in Mrs. Crane’s bathroom.

On the underside of the sink counter in Mrs.Crane’s bathroom are inscriptions etched into marble by the craftsmen who installed the bowl. They had good reason to be proud of their work. Here’s what they wrote: “This bowl was set Dec. 29, 1927 by James Morton of Beverly; George Landers of Wenham; Wilfred Burns of Ipswich; Chet Bates of Revere. Weather was stormy. South East Gale with rain.” I find this record, left by 4 local men—along with a weather report—to be enormously moving…

And so we complete our tour of the interior of the Cranes’ Great House with this reminder that each and every person who participated in its creation clearly did so with a measure of passion and pride. And those same good qualities have recently been returned to the Estate: embodied now by the Trustees staff members who manage the House and Grounds with energy and enthusiasm.

With their scholarship, vigorous fund-raising, and unabashed love for the Place, the Trustees of Reservations are now supervising a program of massive restoration: they’ve banished the dust– and the ghosts–and are bringing Castle Hill’s House and Gardens back to life.

For students of architecture and interior decoration, time spent in close examination of the Cranes’ Great House is as good as graduate-level instruction. Each room of David Adler’s carefully-considered interior presents a pattern-book of history and ideas, if one knows to look to his walls for guidance.

And for those who simply wish to experience the magical aura created for Castle Hill’s impossibly-affluent former occupants, nothing can beat taking a stroll outside, up and down and along the undulating lawns of the Grand Allee’s half mile path to the Ocean…which we’ll soon do.

Although the Cranes’ Great House is an invaluable resource for the study of design, were it not for the magnificent Grand Allee that links House to Ocean, the mansion that David Adler built for Richard Teller Crane Junior could very well be regarded as just one more entry in the long inventory of gargantuan houses which were erected by the first and second generations of America’s captains of industry and finance. After the Civil War, newly-minted fortunes allowed America’s wealthiest families to build themselves palatial homes and extravagant gardens. In 1873, Mark Twain, who considered such displays of affluence to be ridiculous and wasteful, christened those times with the pejorative and wonderful name: “The Gilded Age.” Newport, Rhode Island boasts the greatest concentration of these gilded summer “cottages;” disingenuously-called as such by their occupants, who paused in their fancy digs for no more than a month or two, during summertime.

Marble House, in Newport, Rhode Island, was begun in 1898 and completed in 1901. I took this photo on the morning of Sept. 11, 2014.

The Elms, also in Newport, was begun in 1888 and finished in 1892. I took this photo on the afternoon of Sept. 11, 2014.

By the turn of the century the Gilded Age had morphed into a period that historians have designated the Country Place Era. Exactly when Gilt was replaced by Country is debated; some historians date the Gilded Age from 1870 to 1900, whereas others nitpick that the American Country Place Era began in 1890. But there’s no doubt about when the extended season of great-Estate-making in America finally began to sputter to a halt. In 1930, the onset of the Great Depression saw to that!

In 1910, as the first rendition of their Great House arose, the Cranes hired Frederick Law Olmsted’s sons (who had successfully continued the firm founded by their father) to plan the gardens at Castle Hill. The bowling green and the hedge maze that I’ve already told you about (which were on the east side of the house, adjacent to the Living Room, and the upstairs Sitting Room) along with a large, walled Italian garden for the western slopes below the house, were laid out. But when it came to Olmsted Brothers’ proposal for the area next to the north terrace and lawn, Mrs. Florence Crane balked. Florence knew that the open hayfield favored by the Olmsteds was wrong; she understood that her home (even this version….her despised Italian Villa) needed a landscape feature which would link her house to the sea.

Life, with preposterous serendipity, provided Mrs. Crane with a Solution, in the person of their Argilla Road neighbor, landscape architect Arthur A. Shurcliff.

Landscape architect Arthur Shurcliff (born 1865, died 1957) established Harvard’s School of Landscape Design in 1900; this was the first school of its kind in the world. Shurcliff is most famous for his role as Chief Landscape Architect for the restoration and recreation of the gardens, landscape, and town planning of Colonial Williamsburg, Virginia.

In 1913, Shurcliff, who’d initially been retained to advise the Cranes about installing drainage and irrigation systems at Castle Hill, was then assigned the task of formalizing a connection between the Great House, and the Atlantic Ocean. His solution: an undulating lawn, measuring 160 feet wide—defined on each long side by double rows of clipped hedging and trees—which would stretch out over the entire half-mile distance from Great House to Ocean.

In 2012, to celebrate the completion of their renovation of Castle Hill’s Grand Allee, the Trustees of Reservations published a booklet: A GRAND UNDERTAKING—THE GRAND ALLEE AT CASTLE HILL ON THE CRANE ESTATE.

The Trustees of Reservations have restored the plantings along the Grand Allee, and are now repairing the Casino Complex. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations.

Written by Laurie O’Reilly and April Austin, A GRAND UNDERTAKING provides a good summary of Shurcliff’s design. Since I’m loathe to rewrite histories that have already been well-told, here’s an excerpt from O’Reilly and Austin’s report:

“He suggested a Mall—a grassy expanse bordered by trees. Shurcliff’s brilliance shows in the deceptively simple arrangement he devised, a design that took ten years to mature to its ideal height. Shurcliff chose trees that grew well in this part of the country. The inner hedge was Norway spruce, sheared to a height of 12 to 15 feet to provide a green-curtained backdrop to classical sculpture. [Nearest to the House] the hedge was backed by a row of white pine, and the last 500 feet were edged with red cedar. The resulting grand avenue, or greensward, is unique in American landscape design. While other estates of the so-called Country Place Era boasted similar features, none approaches the size or scale of that at the Crane Estate.”

As Shurcliff thought about how to sculpt the rise and fall of slopes along his half-mile Allee , he also found a way to seamlessly incorporate the Casino Complex, which had already been designed by architects Shepley, Rutan and Coolidge. By tucking the Casino’s ballroom and bachelors’ quarters below a cut into the hillside that formed the uppermost portion of the Allee, Shurcliff and the architects preserved the Great House’s uninterrupted line of sight to the Ocean. The Casino’s saltwater swimming pool was then positioned at the center of a large new terrace that was erected slightly above the floor of the first of two little valleys that had been formed, along the course of the Allee.

Shurcliff’s extensive re-grading of the entire stretch of land between the House and the Sea–from the top of the Great House’s terrace and north lawn, down past the “entertainment hub” of the Casino, and

then further along two more carefully-formed hills—allowed him to control the views, from almost every vantage point. The Casino becomes a large, elegant object in a game of Hide and Seek. First you don’t see it. Then you do. Up another hill and then down into another valley, and finally to the Ocean…and the Casino’s gone again. Wherever you are on your Allee-walk, you see only what Arthur Shurcliff wanted you to see. The man was a Land-Sculpting-Magician!

It’s high time now to get to our promised, Grand Allee leg-stretch. My photos of the Allee will correspond to various stops along the way, on the half-mile stroll that Leo and I took, during our August 16th visit, as we headed away from the Great House, and toward the Ocean.

On the north terrace of the Great House, we share a Griffin’s view of the Allee (more in a while about the Griffin and his Twin).

We’re a bit farther along, on the upper-most stretch of the Allee. In 2010, the Trustees began to restore the Grand Allee. Their aim: the removal of 7000 old, overgrown trees, many of which had totally obscured the classical statues at the edges. By the end of 2012, 7000 vigorous new spruces and pines had been planted. Quite a mind-boggling Garden Chore…

On both long sides of the Allee, secondary, narrower hedged paths run parallel to the main greensward. Here, we’re pausing at a point that’s just above the Casino balustrade.

One of the two stairways which lead down to the Casino’s 12,000 square foot courtyard. “Casino” is Italian, for “Little House.”

The former site of the Casino’s saltwater swimming pool, which was installed in 1915. During the 1940s, Mrs. Crane decided the pool was a safety hazard, and had it filled with soil. A brick pathway laid in herringbone pattern encircles an inner path of irregular marble pavers. In the future, I hope that the Trustees will reinstall some sort of large water feature at the center of this space.

Vintage photo of the Casino’s swimming pool, as it appeared in the 1920s. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

Vintage photo of the Casino Complex, as it appeared from 1915 until 1949. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

Vintage photo of the Casino Complex, with the second version of the Great House, at the top of the hill. The upper reaches of the Allee looked like this, from 1928 until 1949. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

Detail of entrance to one of the pavilions of the Casino Complex, where statues of Bacchus are ready to welcome merrymakers.

View of the construction site at the Casino Complex. I took this photo on August 12, 2014. The Trustees’ million-dollar Casino reconstruction project will soon be completed.

As we proceed beyond the Casino Complex, and climb the slope of another hill, we briefly turn backwards, for this view.

This scene from the 1987 movie THE WITCHES OF EASTWICK has Jack Nicholson (aka Daryl Van Horne; aka Lucifer) banqueting at the top of the same hillock that we’ve just walked to.

After you’ve visited the Crane Estate, rent the movie. It’s fun to identify the exterior locations used for the film, which is charming and very entertaining…all except for the final 10 minutes, when special effects run amok.

Turning away from memories of Jack’s banquet, we continue our trek toward the Ocean, but the Atlantic has become invisible, thanks to Arthur Shurcliff’s control of our Allee views.

We’re reached the top of the Allee’s final hill, and look inland, back toward the Great House. Once again, Shurcliff has hidden the Casino Complex.

This is the only “garden ornament” at the Ocean End of the Allee: a tiny Geodetic Survey Marker…which is rather an anti-climax after Arthur Shurcliff’s masterfully-orchestrated, half-mile-long swath of green. A series of low stone benches placed here on the promontory would quietly punctuate the Allee’s termination, and would also provide a welcome resting spot.

Leo and I retraced the half-mile, back toward the Great House, and then headed west across a field, where we encountered Other Humans. This knot of people (along with the sudden appearance overhead of an airplane that was beginning its ascent from Boston’s Logan Airport), was a jolt….for a long while, we’d felt that Castle Hill was ours alone.

We’re by the west side of the Great House, about to start down this steep path, which leads to the Formal Italian Garden.

The Formal Italian Garden was built from 1910 to 1912, while the first version of the Cranes’ Great House was also being constructed. Per the Trustees:

“designed by the Olmsted Brothers, this was the first and most elaborate of the estate’s Formal Garden spaces. One end features a columned balcony above a fountain and pool. Two octagonal tea houses are linked by a pergola at the other end. A central garden included ornamental flower beds. The Olmsteds coordinated with architects Shepley, Rutan & Coolidge on the design of the garden structures.”

The sunken, central area of the Formal Italian Garden can also be seen from this lightly-forested slope, which is to the east of the Garden.

Although the Trustees’ design notes don’t mention it, a small, circular “ante-room” was also built, to serve as prelude to the balcony which overlooks the central part of the Italian Garden. This round courtyard, with simple, slightly plump columns which at one point certainly supported pergola beams, feels powerful and primitive. Here’s my first view of that “ante room.”

Another view of the entry to the Formal Italian Garden. This intimate ante-room is one of my favorite parts of the Crane Estate.

On August 25th, when Holly Alderman accompanied me to Castle Hill, she agreed with me about the magical ambience of this little garden room.

A broad balcony overlooks the Italian Garden. During the Cranes’ tenure–and despite the Italian style of the garden’s structure–the annuals and perennials that were grown here were traditional American favorites (larkspur, Canterbury bells, Madonna lilies), but limited to those plants whose flower colors would cooperate with Mrs. Crane’s scheme of white, blue and pink.

Vintage photo of the sunken area of the Italian Garden, circa 1915. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center.

Another vintage photo of the Italian Garden, circa 1915. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

I look forward to the day when the Italian Garden’s fountain is again spraying water into a filled pool.

At the western-most end of the Italian Garden is a pergola, which connects two octagonal tea houses.

Vintage photo of those same pergola shadows, circa 1915. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

We’re exiting the Italian Garden, through the wrought iron gates at its western end. Across the street are urns which mark the pathway that leads further downhill, to the Rose Garden.

Onward now, to the Land That Time Almost Forgot, otherwise known as Mrs. Crane’s Rose Garden. Seen from the road that lies just above the Rose Garden,

this shaggy and quite enticing scene presents itself.

Vintage photo of path to Rose Garden, circa 1930s. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

But so you can enjoy this final, major garden area of the Crane Estate (which was built during 1913 and 1914), I—wearing my reporter’s hat— did some gentle trespassing. Here’s what the Trustees have to say about the garden: “Designed by Arthur Shurcliff, this sunken garden ‘room’ lies across the road from the gates of the Formal or Italian Garden. The Rose Garden replaced a ‘wild garden’ designed by the Olmsted Brothers. Circular and framed on three sides by a walkway covered with a wooden pergola, the Rose Garden once boasted plantings laid out by Marblehead rosarian Harriett Risley Foote in four beds that encircled a central rose bed, pool and fountain.”

This was a ROSE GARDEN—par excellence—with 600 varieties of roses that were planted by the woman who eventually wrote THE book on rose cultivation.

Mrs. Foote’s BOOK, in which she described her rose-growing secrets in detail, was published in 1948. Her methods were the result of years of trial and error in her own garden, where she cultivated nearly 10,000 varieties of roses.

Vintage photo of the Rose Garden, circa 1915. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

Vintage photo of Rose Garden’s pergola, circa 1915. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

Vintage photo of the Rose Garden, with its central fountain and pool, circa 1915. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

Hand-colored, vintage photo of the Crane family in their Rose Garden, circa 1915. Left to right: Richard Teller Crane Junior, Cornelius Crane, Miss Florence Crane, Mrs. Florence H. Crane. Image courtesy of the Trustees of Reservations, Archives & Research Center

Here now, are my photos of the interior of the still-enchanting Rose Garden, which, though long rid of its flowers, is yet an exquisite and hushed and spiritual place. Arthur Shurcliff built good bones here: the ruins which remain speak of his sensitivity to the greater landscape, and serve as testimonials to his infallible sense of proportion.

A forest of columns, on a raised terrace which girdles the Rose Garden on three sides. In the distance you can see a glimmer of water, which is Ipswich Harbor.

The now-dry fountain and pool at the center of the Rose Garden, with a better view of Ipswich Harbor

Much of the concrete poured in America during the early part of the 20th century is deteriorating, due to a condition known as Alkalai-Silica-Reactivity. Modern-day concrete mixes, which are less crumble-prone, may eventually be used to replicate the failing pieces of the Rose Garden. When I see the extreme damage that Nature has inflicted upon the concrete garden decorations at Castle Hill, I wonder why the designers did not choose to use granite, or marble, instead.

On August 25th, this deer, who had just exited the Rose Garden, politely paused so that I might take her picture. She then scampered down the path, toward Ipswich Harbor.

After my deer-encounter, I turned back into the Rose Garden. Uphill, the dome of an Italian Garden Tea House is visible.

As I prepared to tiptoe out of the Rose Garden, I took one last look at its graceful curves, which are enhanced by the well-mown lawn. I also reminded myself that, during the Crane family’s tenure, the slope below the Rose Garden was bare of undergrowth, which allowed a wide vista of Ipswich Harbor. Although I shouldn’t admit this, I find the strength and simplicity of the Rose Garden as it now is—in all of its crumbling splendor: with its bare columns reaching for blue sky, while casting shadows across grass—far more beautiful than it was, during its rose-filled heyday.

We’ll wander back uphill now, toward the north terrace of the Great House…

…where we’ll see one last thing, before declaring that we’ve had a Fine Day, as we’ve explored the amazing world that Richard Teller Crane Junior created for his family.

Inscription on the base of one of the two cast-lead Griffins given to R.T.Crane Junior, upon the completion in 1928 of his second Great House at Castle Hill.

Per the Trustees’ design notes: “The most distinctive sculptures associated with the property are the pair of lead griffins that watch over the north terrace. These sculptures were a gift to Mr. Crane from employees, after completion of the house, and bear a dedication with a date of 1928. The sculptures were designed by Paul Manship, a prolific artist in his own time, who is today best known for his Art Deco PROMETHEUS FOUNTAIN (1932) at Rockefeller Center, in New York. Griffins are mythological beasts—

half eagle/half lion—that symbolize the combined properties of watchfulness and courage. As Adler had intended the Crane mansion to resemble a late 17th century English country house, these highly stylized Art Deco sculptures are the only feature of the house exterior that date it to its own time.”

Despite a sign which pleads: “Please Help Us Care For Our Griffins By Not Climbing On Them,” kids cannot help themselves…