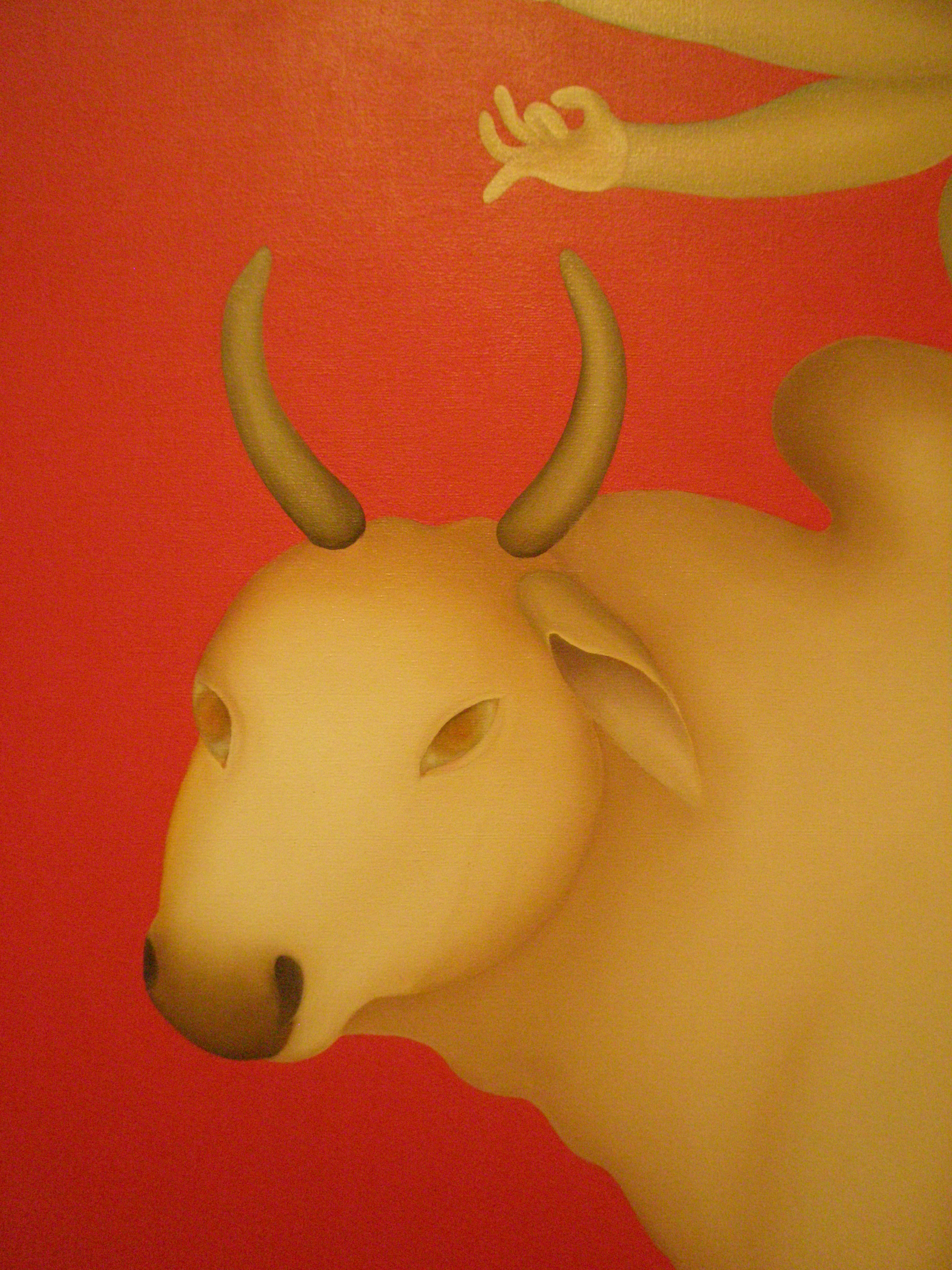

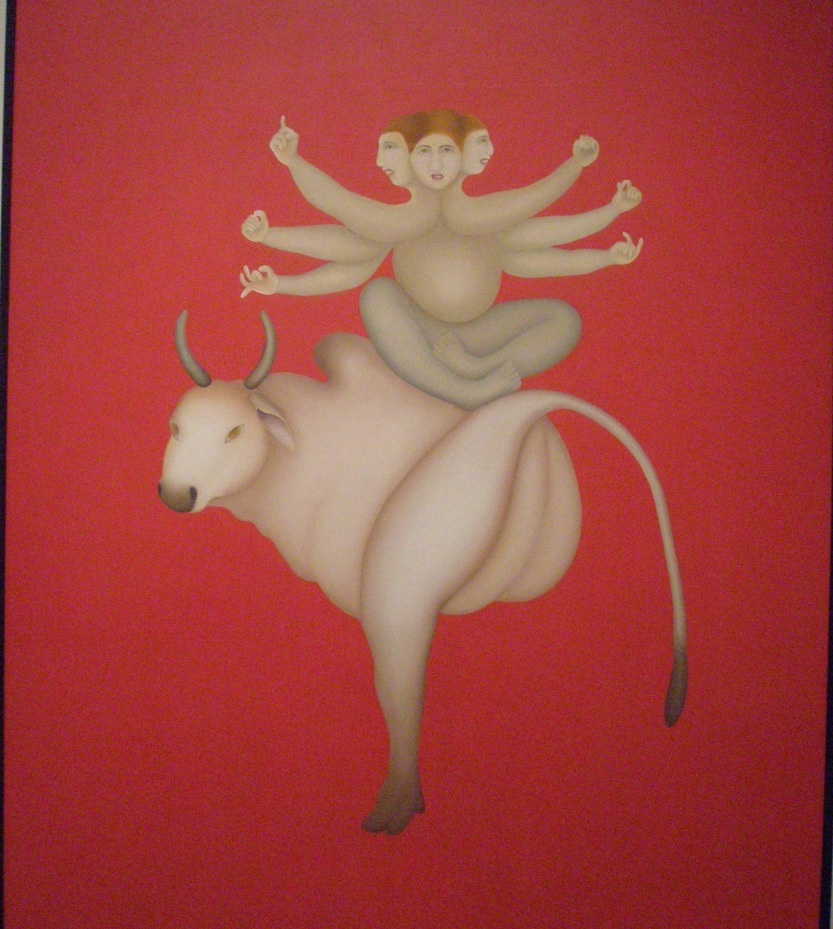

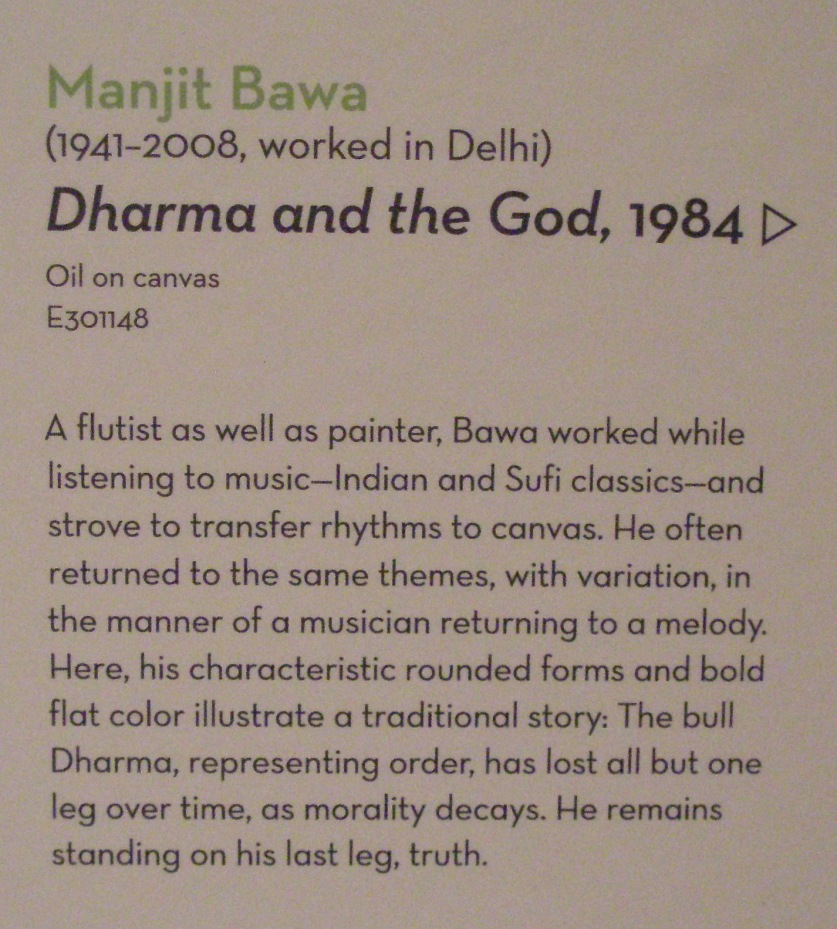

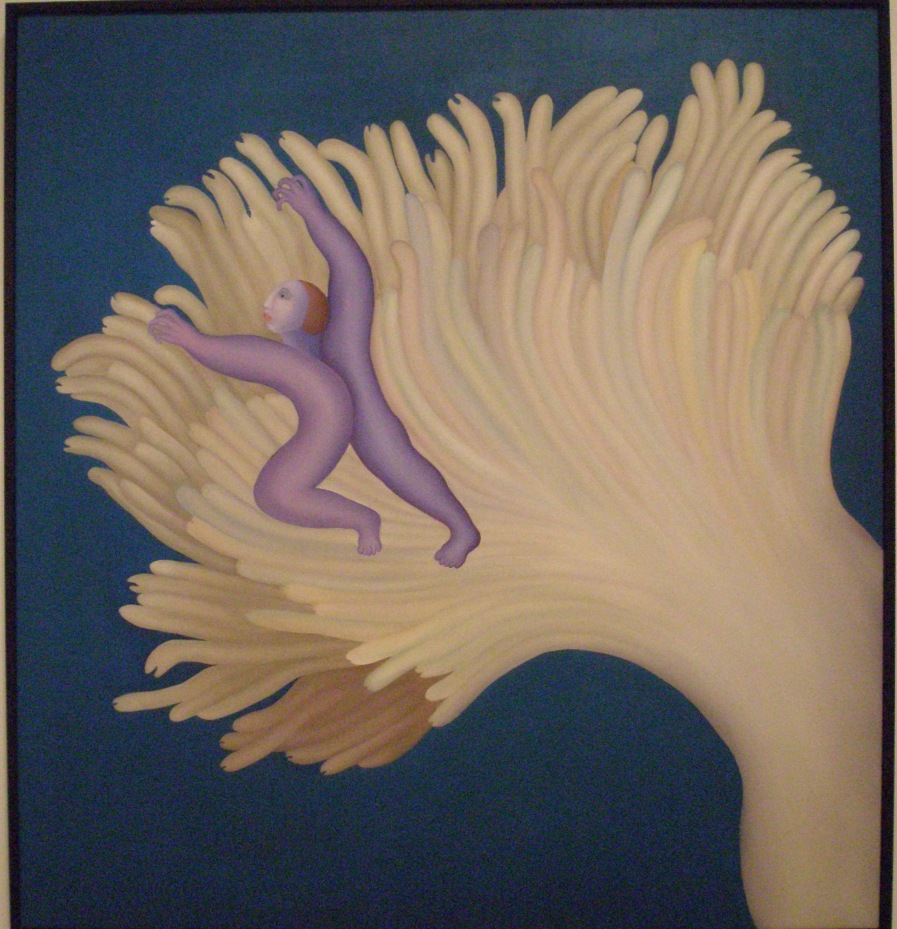

Detail of Manjit Bawa’s painting DHARMA & THE GOD, part of the Peabody Essex Museum’s new show of modern Indian art: MIDNIGHT TO THE BOOM–PAINTING IN INDIA AFTER INDEPENDENCE.

February 2013. Salem, Massachusetts.

As promised in my previous Armchair Traveler Diary, I’m lingering a bit longer in Salem, Massachusetts…this time for an extended look at the considerable wonders of the Peabody Essex Museum.

If we’re lazy, we’re content to regard a museum as a series of rooms into which thousands upon thousands of bits of cultural booty have been stuffed. That booty then rests passively and quietly; its only job is to catch our attention, should we happen to find ourselves wanting a taste of art. Rarely during our gallery-wanderings do we contemplate how, or why, the gallery-sausage gets made. But it behooves us to understand that the Peabody Essex Museum (hereafter called PEM, to save us many mouthfuls of words) exists because of the persistent (over 200 years of persistence!), mule-stubborn efforts of its multiple founders–and their descendants– to acquire and display treasures from Salem’s Golden Age, and from the Far Corners of the World; to coordinate and consolidate; to fund and build (and then to consolidate some more, and to build some more, and to fund some more…ad infinitum). In 1799 the East India Marine Society was founded by Salem sea captains who’d sailed beyond either Cape Horn, or the Cape of Good Hope. Those mariners yearned to display the “natural and artificial curiosities” from Asia and Africa and India that they’d brought back to America.

Although the Salem of today can seem a sleepy and somewhat battered-looking provincial city of 41,000 souls, just a bit of careful inspection of the holdings of the PEM is all it takes to be reminded of the greatness that Salem achieved as the home port of some of the most adventuresome and successful ocean traders the Earth has ever known. The exotic cargoes which those sailors brought back ensured that Salem’s Atlantic air would be forever tinged with the essences of the wider world, and especially the essences of the Far East.

The PEM’s website nicely summarizes how partnerships between the East India Marine Society and Salem’s other scholarly institutions evolved into today’s Museum:

“Salem was also home to the Essex Historical Society (founded in 1821), which celebrated the area’s rich history, and the Essex County Natural History Society (founded in 1833), which focused on the county’s natural wonders. In 1848 these two organizations merged to form the Essex Institute. In the late 1860s, the Essex Institute refined its mission to the collection of regional art, history and architecture. In so doing, it transferred its natural history and archaeology collections to the East India Marine Society’s descendent organization, the Peabody Academy of Science. In turn, the Peabody, renamed for its great benefactor, the philanthropist George Peabody, transferred its historical collections to the Essex. In the early 20th century the Peabody Academy of Science changed its name to the Peabody Museum of Salem, and continued to focus on collecting international art and culture. Capitalizing on growing interest in early American architecture and historic preservation, the Essex Institute acquired many important historic houses. With their physical proximity, closely connected boards and overlapping collections, the Essex and the Peabody merged, and the consolidation of these two organizations was effected in July 1992.”

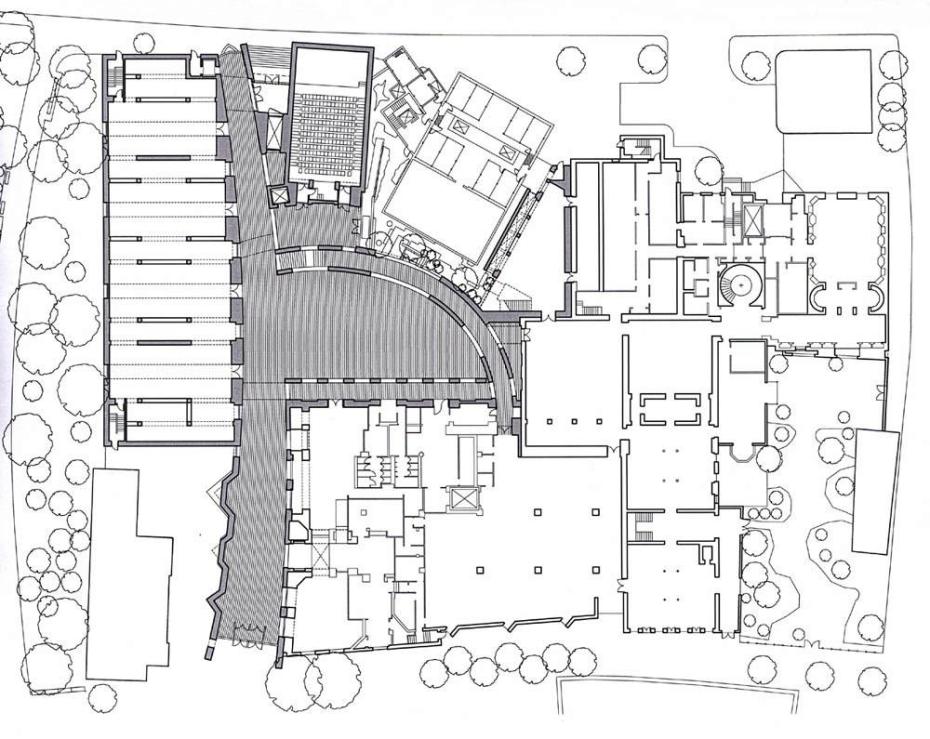

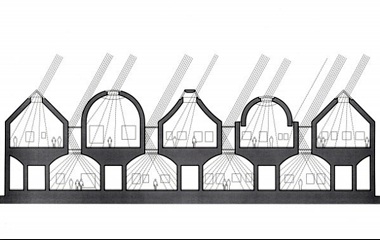

The PEM’s collections reflect Salem’s deeply muscular ties to foreign lands: in past days, and on into the present. And the Museum’s expertise at melding history and culture in a manner that keeps our vision fresh is also equaled by their architects’ finesse: the galleries’ contents are housed in rooms which present the PEM’s collections in sensitive and surprising and beautiful ways. Museum-fatigue, which afflicts even seasoned art-lookers like myself, rarely occurs at the PEM.

So now… my modest offering: a mini-Baedeker to the Peabody Essex Museum!

Even on overcast days, and without artificial illumination, the Front Entry Hall is filled with light.

There could be no better emblem of Salem’s cosmopolitan and profoundly international roots than the PEM. The museum’s holdings—collections of American art; Asian, Oceanic and African art; Asian export art; Maritime art; libraries with over 400,000 books, manuscripts and documents; and 22 buildings built by generations of Salem’s most successful, seafaring merchants….along with Yin Yu Tang, an entire, late 18th century Chinese house that’s been transplanted from Anhui province to the Museum’s campus—represent long fingers of history, which are now gracefully intertwined to hold the PEM’s treasures.

And unless she’d done her travel-homework, a Salem-visitor might well have strolled along Essex Street toward the PEM’s main galleries, unaware that many of the fine buildings she’d passed were also part of the Museum’s campus. But since it’s my job to have half a clue about where I’m going…at least some of the time…I’ll pass along these architectural crib-notes about a few of the Museum’s city-center holdings. But remember, if you hanker to get inside of these houses, it’s best to visit Salem during the warmer months… in wintertime, many of the historic buildings are buttoned-shut.

Gardner-Pingree House. 128 Essex St. One of the most outstanding Adamesque Federal town

houses in America. Built in 1804…perfectly proportioned…the best of the best. Design attributed to Samuel McIntire.

Crowninshield-Bentley House. 126 Essex St. The epitome of a Georgian Colonial house..presenting a chaste and timeless face to the world. Built in 1727.

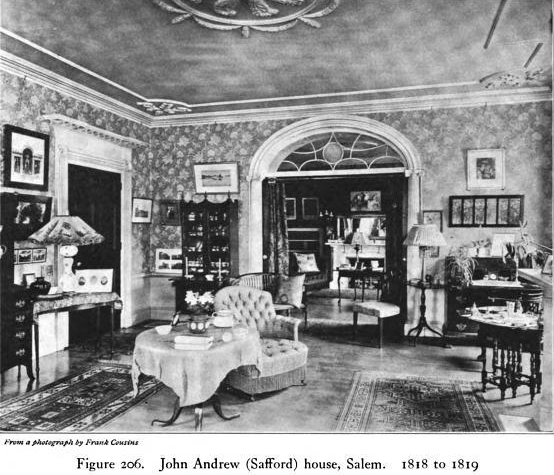

In my previous Salem-article, I ran this view of the Andrew-Safford House and Federal Garden, as seen from my lovely 5th floor room at the Hawthorne Hotel.

Andrew-Safford House. 13 Washington Square West at Brown St. This is considered one of the most important late Federal-era houses in New England, but the more I consider its hodge-podge-ish excess of architectural elements, the more chaotic and ungainly and nouveau riche this house seems. Built in 1819.

A chilly winter’s day in the Federal Garden. Derby-Beebe Summer House, with John Ward House in background.

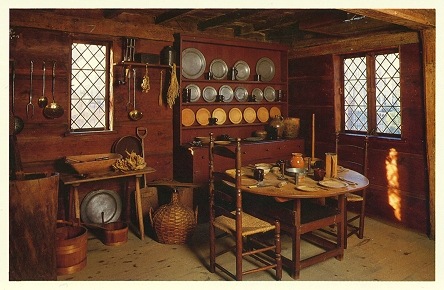

John Ward House. Built in 1684. At Brown Street opposite Howard, in the Federal Gardens. One of New England’s best examples of a wood-frame-and-clapboard 17th century dwelling…but not nearly as grand as the similarly-formed Turner Mansion (aka The House of the 7 Gables, which was built in 1668).

On January 15th, I made my first visit to the PEM, drawn there by HATS, an exhibition curated by the milliner Stephen Jones, in cooperation with London’s Victoria & Albert Museum (which—with apologies to the PEM—is my Very Favorite Museum in the World…the treasure-trove inside of which I dream of being locked, alone…and overnight.).

London’s Victoria & Albert Museum (my favorite Museum on the Planet): Partner with the Peabody Essex Museum, in their

exhibition HATS.

Britain’s Mad Hatters have no proper equivalent in America. If one wishes to obtain a truly FINE crown, it’s to England that one must go, and so I did…which leads me to this brief digression regarding Serious Hats:

In May of 2009 the Royal Horticultural Society invited me to exhibit my garden furniture at the Chelsea Flower Show. On the afternoon of Press Day, the Queen and her gang privately inspect the displays. Each exhibitor is allowed to have a single person on site for that inspection. I’d assumed that, as the designer, I’d be that person, but my sister Pam Quick, who’d kindly come along to help me in my tent, shyly let me know that it would be nice if she could tell her children that she’d seen the Queen. Realizing that spying royalty meant little to me, I consented, and while Pam stood guard for the Visitation, I went to Philip Treacy’s Elizabeth Street shop in Belgravia….

…where I bought a thousand dollar hat (pure, once-in-my-lifetime lunacy!). Two days later, when I returned to Treacy’s to pick up my chapeau (each hat is individually fitted), he happened to be there, and said to me “I hear you’re the American who’d rather buy my hat than meet the Queen!” But, since Treacy is Irish, I suspected he didn’t disapprove of my choice. These days, the only problem with my hat is that I have so few occasions upon which to wear Treacy’s fabulous and surprisingly comfortable creation.

Here are some of the hundreds of mostly-European-made hats that were on display at the PEM (the Show closed in early February, but can still be enjoyed if one buys the exhibition catalogue: HATS AN ANTHOLOGY BY STEPHEN JONES, by Oribe Cullen. From V&A Publishing).

On left: Green Silk Headscarf with applied gray roses. Mitza Bricard for Christian Dior. 1969.

On right: Shoe Hat, by Schiaparelli.

More hats, in the 1st floor American Art Gallery (across from the famous painting of Nathaniel Hawthorne…I wonder what he thought about all that finery….).

After a rather giddy-making hour with the HATS, I sobered up in some of the Museum’s more grown-up, permanent collection spaces….

East India Marine Hall. To this Hall, members of the East India Marine Society brought the art and cultural objects they’d collected as they circled the globe in their ships.

…but I didn’t get TOO sober, thanks to Michael Lin’s exuberantly-painted walls and floors in the H.A. Crosby Forbes Galleries!

Michael Lin decorates floors and walls with vast enlargements of ornamental porcelain and fabric designs. His transformed spaces are wonderful.

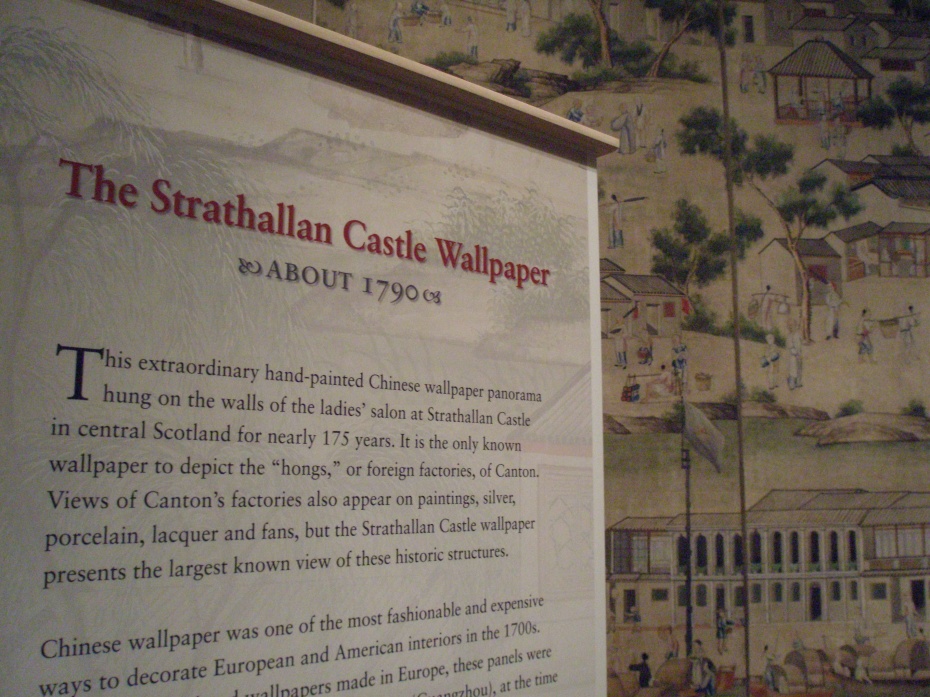

Leaving that phantasmagoric-tea-party, I proceeded into the 2nd floor gallery of Asian Export Art from China…

…and then wandered across to the 2nd floor Japanese Art Gallery…

…and then to the adjoining gallery of Chinese Art:

Chinese Moon Bed. 1876. Satinwood, other woods & ivory. Held together with wooden pegs & 4 butterfly-shaped wedges. There are no screws or nails, and Bed breaks down into 53 major parts.

Accepting that I’d have to come back on another day to properly appreciate the bounty of the Chinese and Japanese Galleries, I tripped downstairs, and passed these splendid twins, who guard the entry to the Garden Restaurant, which is open during clement weather, in the Asian Garden & Terrace.

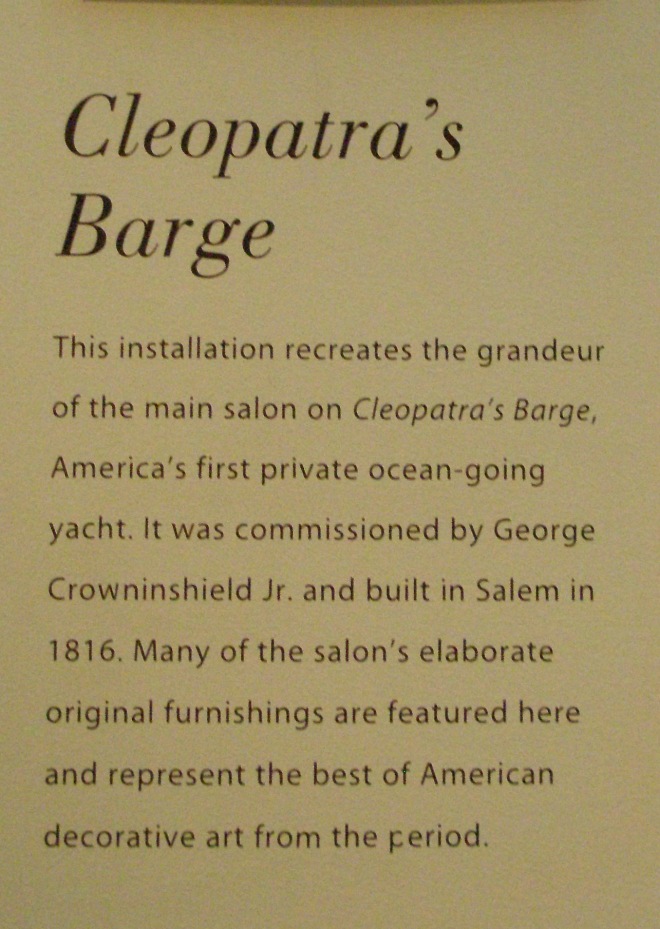

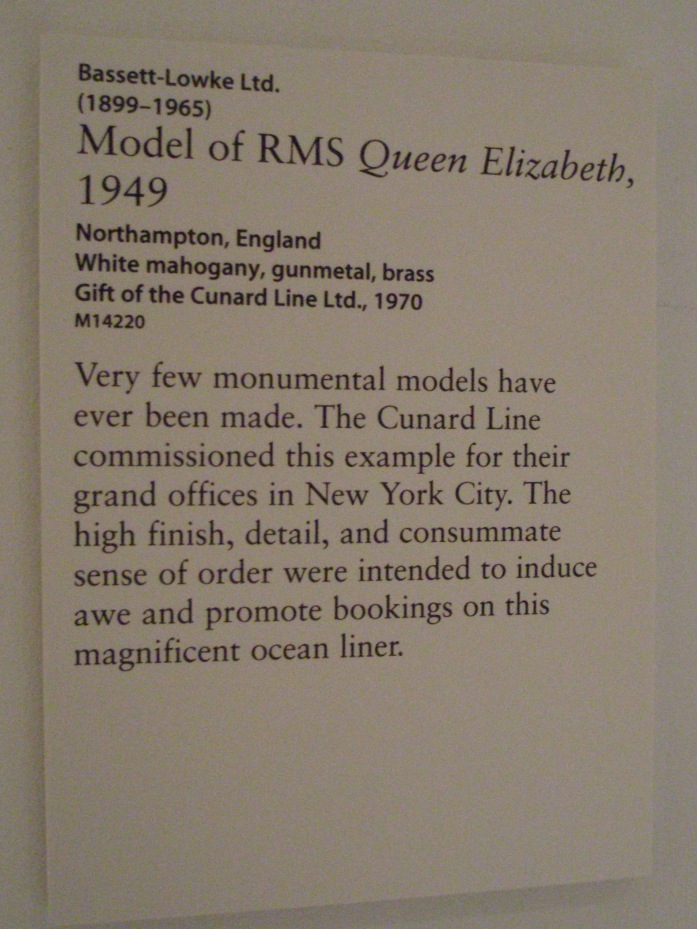

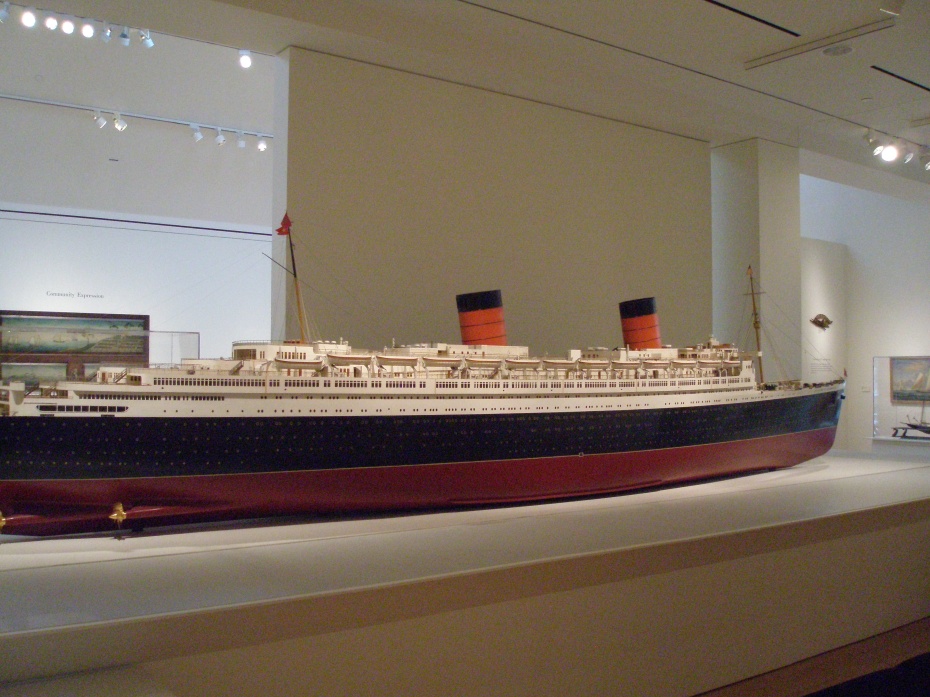

Continuing my fast survey of the galleries, I ended that day’s PEM-tour in the 1st floor Galleries of American Art, Cleopatra’s Barge (no…not THAT Cleopatra!), and Maritime Art.

Mantel from the Nathan Reed House. Designed & carved by none other than our favorite all-round-genius-and-builder-of-beautiful-houses, Samuel McIntire.

Circa 1800.

Cheek to jowl with McIntire’s circa 1800 mantel are two tables, both built in 2006. On the left: an Altar Table. On the right: An Inception Stand.

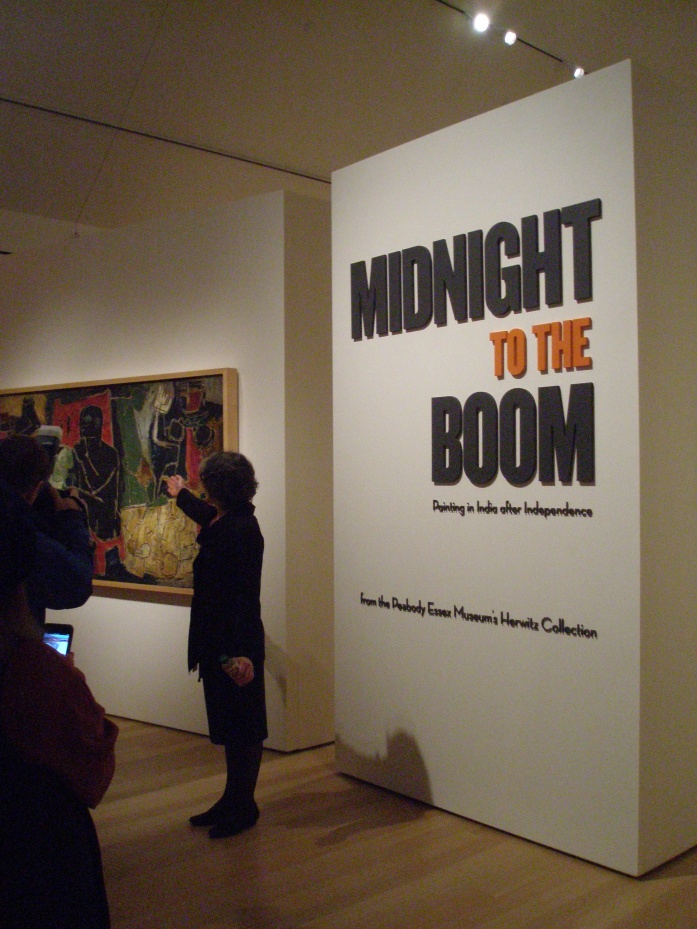

On the snowy morning of January 29th, after a very good night’s sleep at Salem’s Hawthorne Hotel (which I recommend), I was back at PEM’s doorstep, this time to attend a Press Preview Opening Reception for the Museum’s pivotal show of Modern Indian Art. The title of the Show is exhaustingly but necessarily long:

MIDNIGHT TO THE BOOM: PAINTING IN INDIA AFTER INDEPENDENCE, FROM THE PEABODY ESSEX MUSEUM’S HERWITZ COLLECTION.

ON VIEW FEBRUARY 2 THROUGH APRIL 21, 2013.

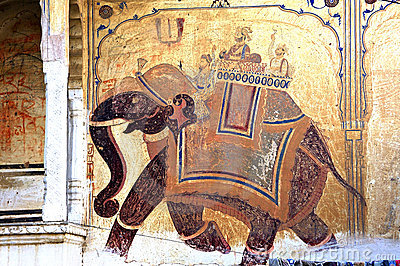

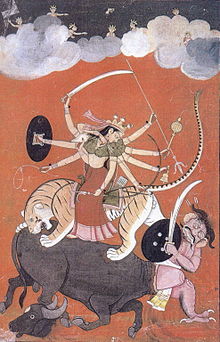

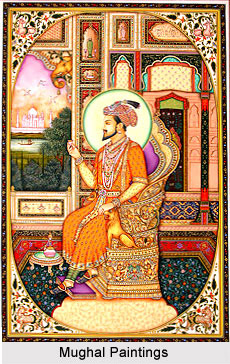

Despite my training in art, and a lifetime of museum-going, I confess that, prior to receiving PEM’s invitation to their Press Preview, I hadn’t given a thought to contemporary Indian art. To me, one could want nothing more than to ogle India’s early frescoes, or temple carvings, or their warrior-Goddesses, or the sublime Mughal miniature paintings.

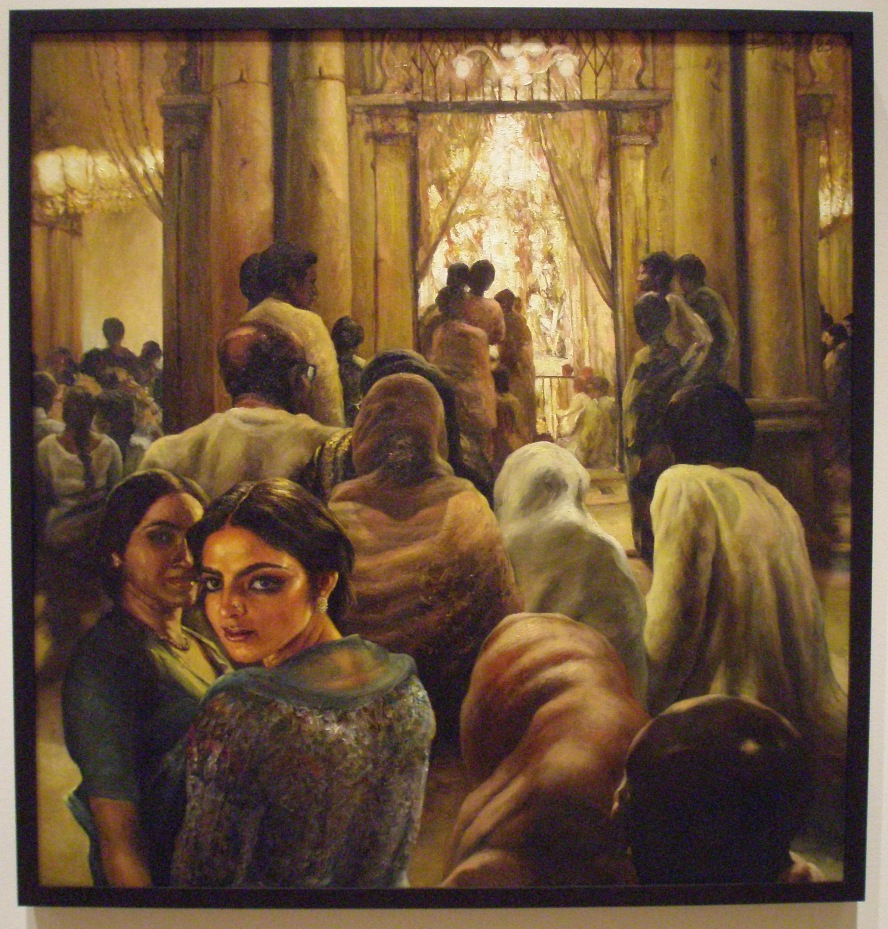

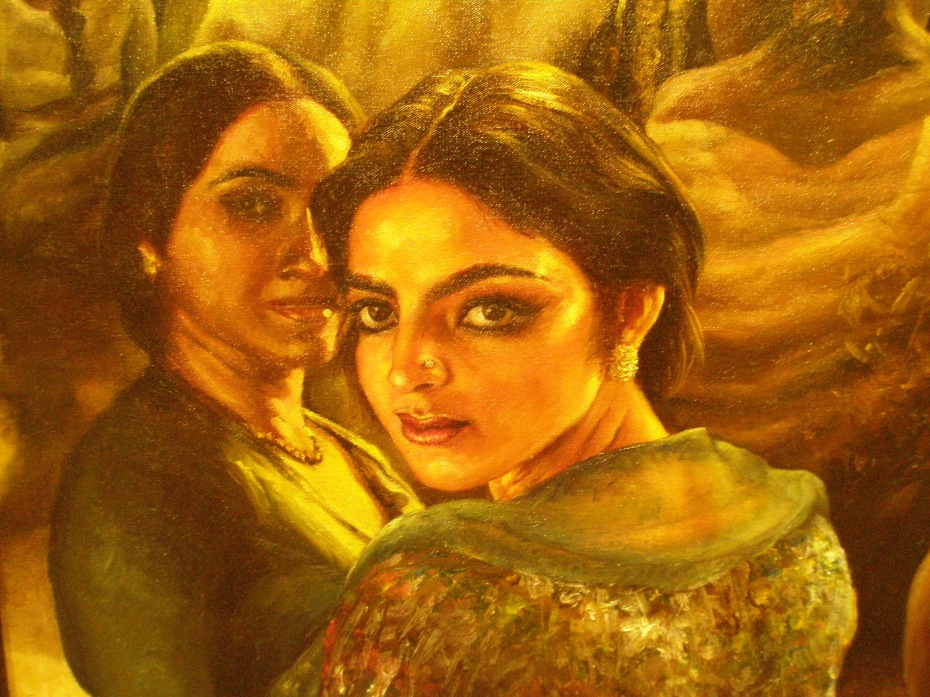

The concept of vital, modern art being done—of a Positive-Painting-Scene on the Indian Subcontinent—simply hadn’t entered my brain. This is proof, once again, that the happiest state of being is near-ignorance, because such ignorance ensures that one need never be bored…there’s always LOTS more to learn! And so, with the help of the Show’s guest curator Susan Bean (and former PEM curator of South Asian and Korean art), who kicked the morning off with an extemporaneous talk that was the model for how all such introductory talks should be, I took baby-steps into the world of art that’s appeared since India’s declaration of independence from Britain (at mid-night, on 15 August 1947….which explains the “Midnight” part of the Show’s title. The “Boom” part refers to the country’s economic expansion during the 1990s.).

The first thing I noticed is that Bean has mounted the Show to give context:to educate her viewers that India’s painters have been well-aware of the work of their global colleagues. Instead of merely posting an exhibition-card explanation about a particular Indian artist’s affection for the paintings a specific Western artist, Bean has hung paintings by Andrew Wyeth, or Paul Cezanne, or Marc Chagall next to those of their Indian counterparts. These groupings illustrate the ways in which painters respond to the work of other painters. Most of the Show’s paintings are concerned with the idiosyncrasies of modern Indian life, but they’ve also been created as part of ongoing dialogues with the art of Western Europe, and of America. And Indian artists are, of course, still engaged in negotiations with their own, splendid visual history. This stew of the culturally-specific, and of the artistically-universal, provides much food for the brain, and for the eye.

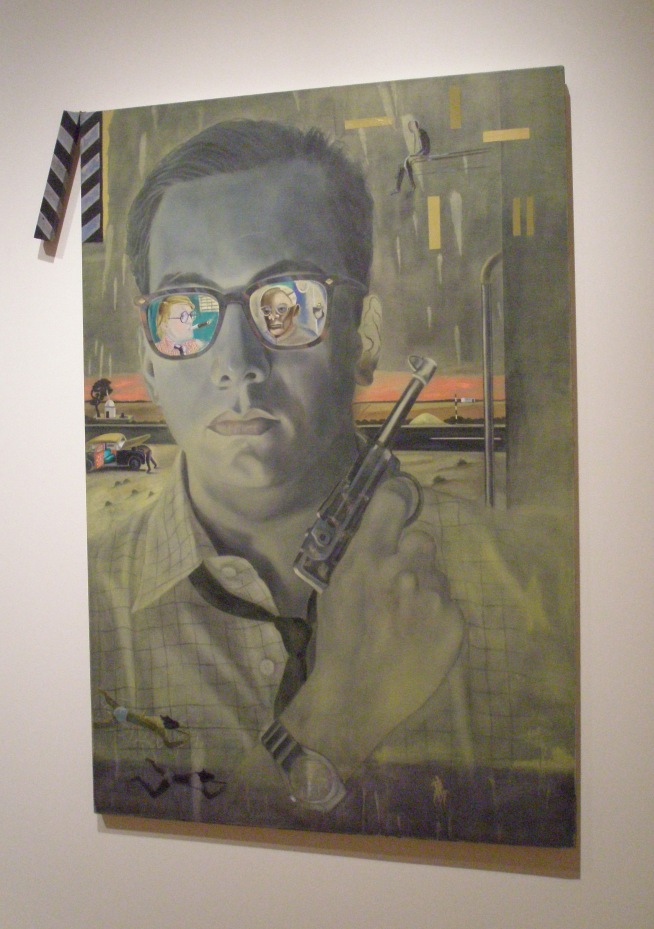

These two, large paintings flank the entrance to the Show:

Atul Dodiya. THE BOMBAY BUNCCANEER. 1994 (note the reflection of the British painter David Hockney in the eyeglass lens)

As our Press Kit summarized: “Nearly 70 works by 23 leading artists were selected from PEM’s Chester & Davida Herwitz Collection—internationally recognized as one of the largest and most important assemblages of modern Indian art outside of India. During a time of enormous political and cultural upheaval, artists working in post-independence India were able to express their individual artistic visions, transcending the limits of the region’s traditional art forms.”

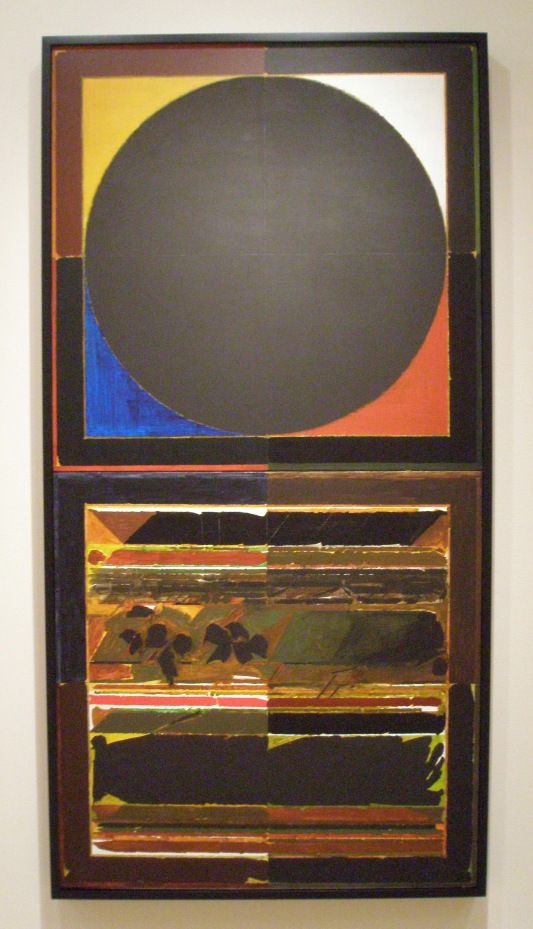

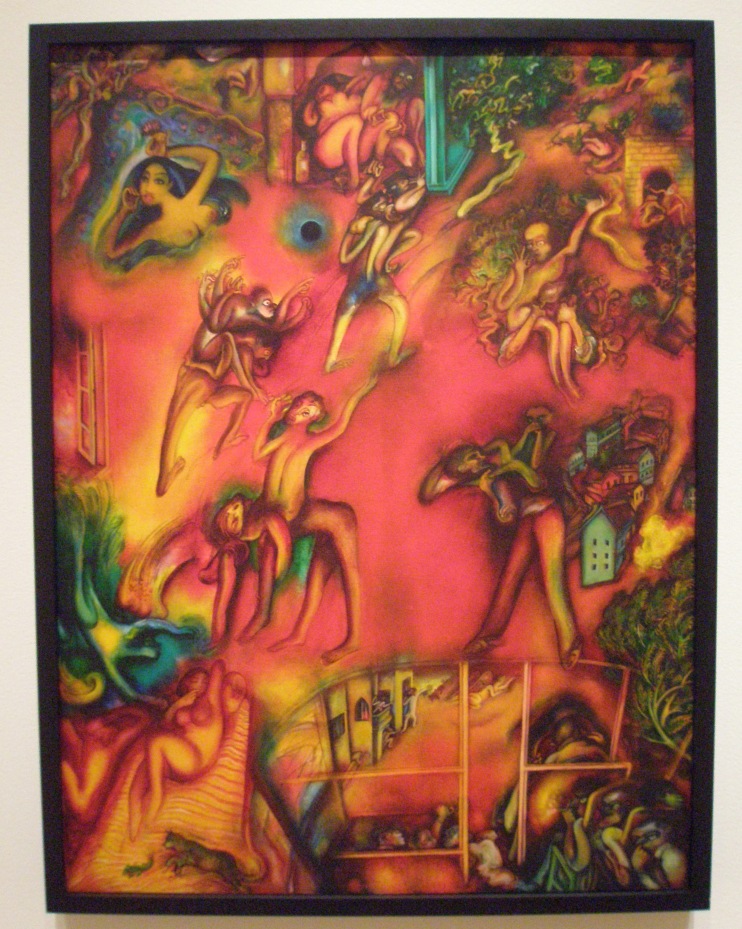

Here are the works that especially caught my eye:

Banner in PEM Atrium for MIDNIGHT TO THE BOOM, featuring painting by

Ranbir Singh Kaleka. FAMILY–1. 1983.

In square-footage terms— compared to the gallery-acreage of the World’s major repositories of art—the Peabody Essex Museum is a humble player in the museum firmament. But because from its earliest, fractured incarnations the PEM has turned its eyes outward—across oceans, toward the hardest-to-reach lands—the PEM’s perspective has always been as bold and broad and inclusive and mind-stretching as that of any of its much-older, much-larger Cousins-in-Curation. Whether borrowing displays of frivolous finery from Europe’s milliners, or introducing India’s modern painters to America’s museum-goers, the PEM reminds us that creative actions never exist in a vacuum and that the human urge to make beautiful and meaningful objects is universal. A well-carved Salem mantel, a carefully-feathered English hat, a masterfully-painted Indian canvas, or an intricately-constructed Chinese bed all spring from an instinct to make a mark with a physical object…an object that will still exist to speak for us after we’re gone…an object whose continued existence carries a message to all the people we’ll never meet about the ideas and things and values we held most dear. Museums are the repositories of these messages, and the Peabody Essex Museum does a particularly fine job of keeping the voices of artists—those whose names we still know, and many more whose names are long-forgotten—ALIVE.

Copyright 2013. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers.

Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express &

written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

0 Responses to Peabody Essex Museum–The Jewel in Salem’s Crown