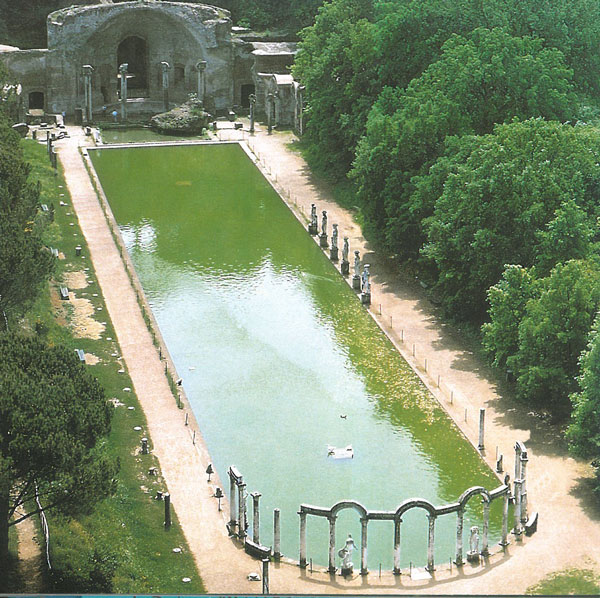

Nan, accompanied by the God of the River Tiber, at the northwest end of the Canopus, a giant pool (measuring 59 feet by 390 feet) which is just one of the many features built upon the vast grounds of the country villa and official residence of the Roman Emperor Hadrian (aka: Publius Aelius Hadrianus Augustus. Born 76 AD, Died 138 AD; ruled as Roman Emperor from

117 AD until his death.). Villa Adriana (Hadrian’s Villa) is one of two UNESCO World Heritage Sites which are located in Tivoli. The other UNESCO Site there is Villa d’Este, which will be the subject of my Tivoli, Part Two.

Early 2018

Finally, Part One of a long-delayed but essential addendum to my article titled “My Recipe For a Stress-Free Week in Rome,” which I published several years ago [see link below].

One of the keys for a happy week’s stay in Rome is to decompress by fleeing the city, every several days. Rome is one of the few places

on Earth to which I’m drawn, over and again. But the often fraught atmosphere of that city — its demented traffic, air pollution, badly-behaved tourists, and jam-packed historical sites — sometimes requires a Retreat, and there are no better — or closer —

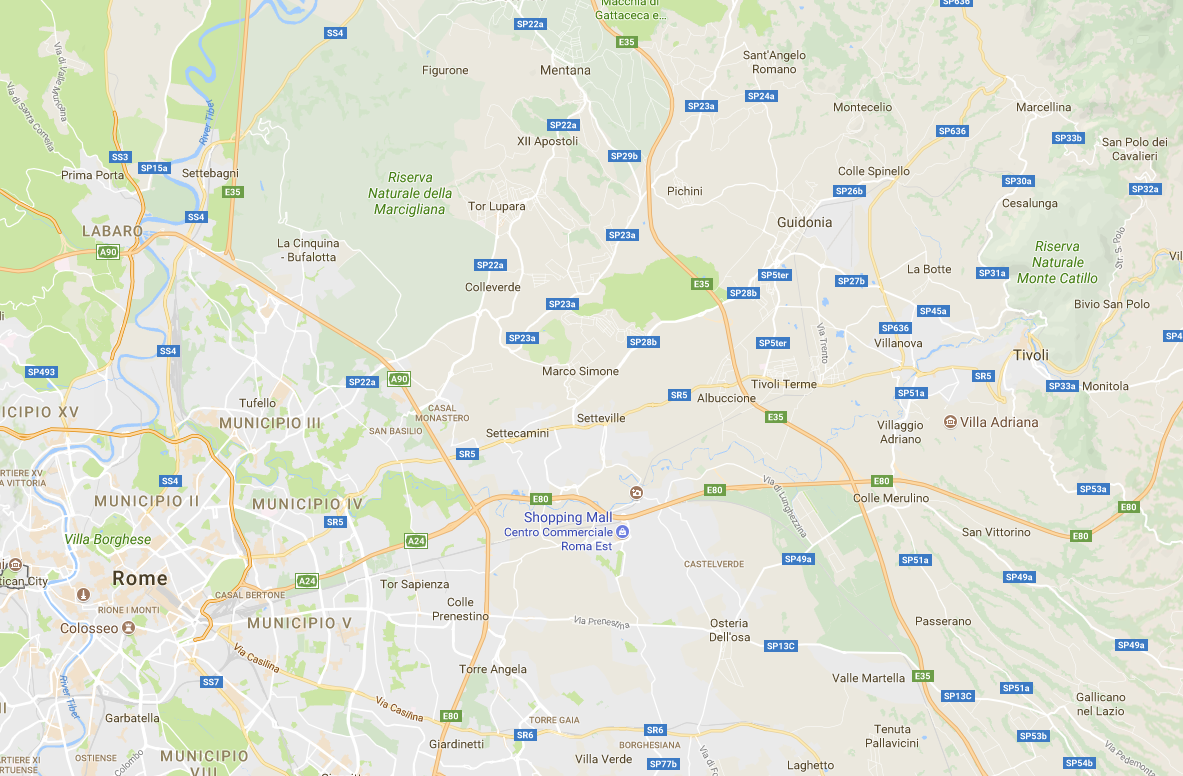

escapes from All That than two UNESCO Heritage Sites in the town of Tivoli, which is 22 miles away , to the northeast of the Rome.

The 22-mile-long drive from Rome to Tivoli will take 50 minutes, once you’ve extricated yourself from Rome’s gridlock. For each of my 3 visits to Tivoli, I’ve hired a taxi for the day….a considerable expense, but one which has allowed me to savor and photograph sites at my own pace. Inexpensive, day-long tours of Tivoli (via bus, originating from Rome) ARE available, but, organized/group travel never serves my purposes, and also makes me VERY crabby.

These incessant travels of mine, made to seek out the most interesting gardens and man-made landscapes, are not undertaken simply so that I can gaze upon all that is beautiful and marvelous. My curiosity about how such places were conceived and constructed is what propels my journeys. I visit each garden, be it vast or tiny, and always get to wondering: had I been this specific designer, living in this particular era, with this raw piece of land at my disposal … had I been cognizant of prevailing tastes and also familiar with the best local artisans, and aware of current construction techniques … had I been in possession of a bank account which equaled that of my predecessor’s … what would I have created here, on this site? With these speculations, I temporarily slip into the times, into the design-minds, and into the boots of these people, who all tried to build their very own versions of paradise.

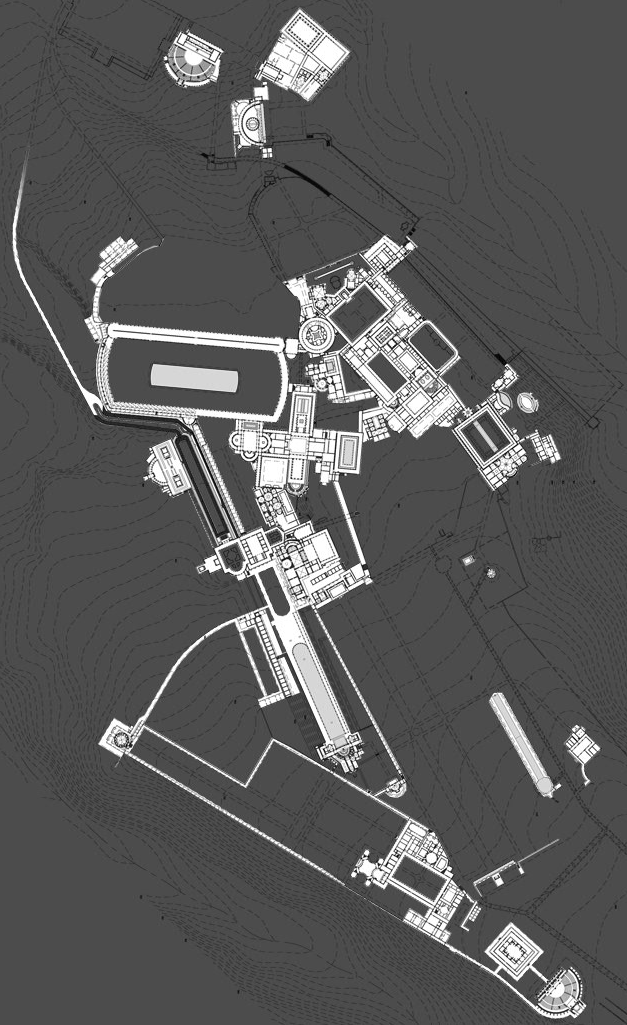

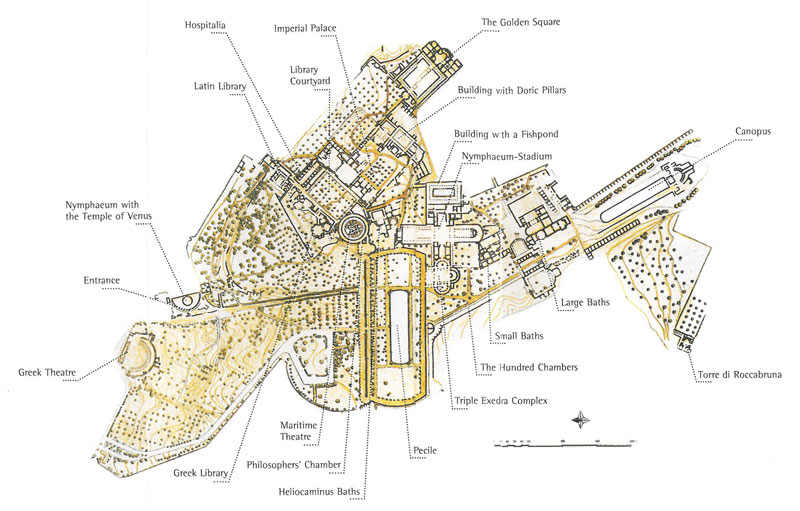

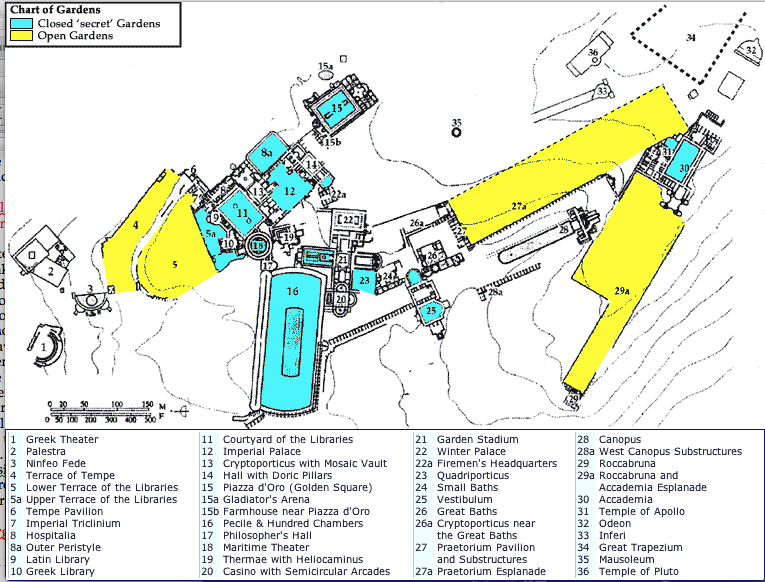

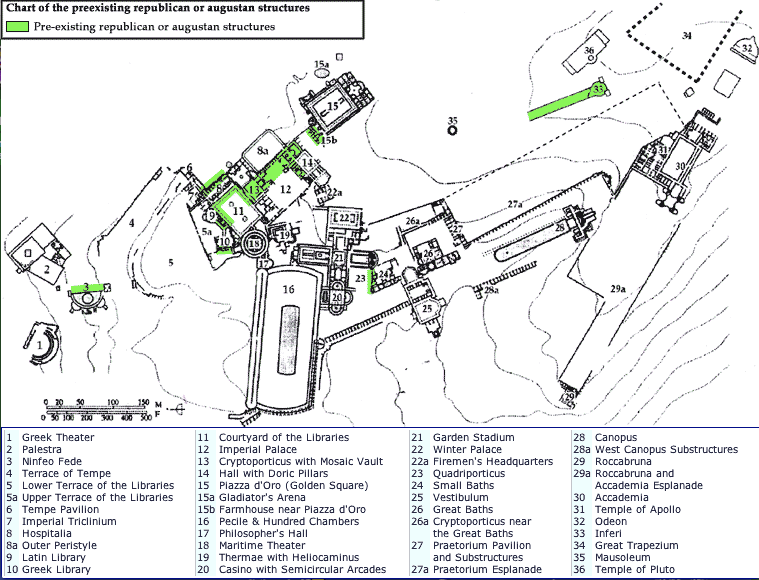

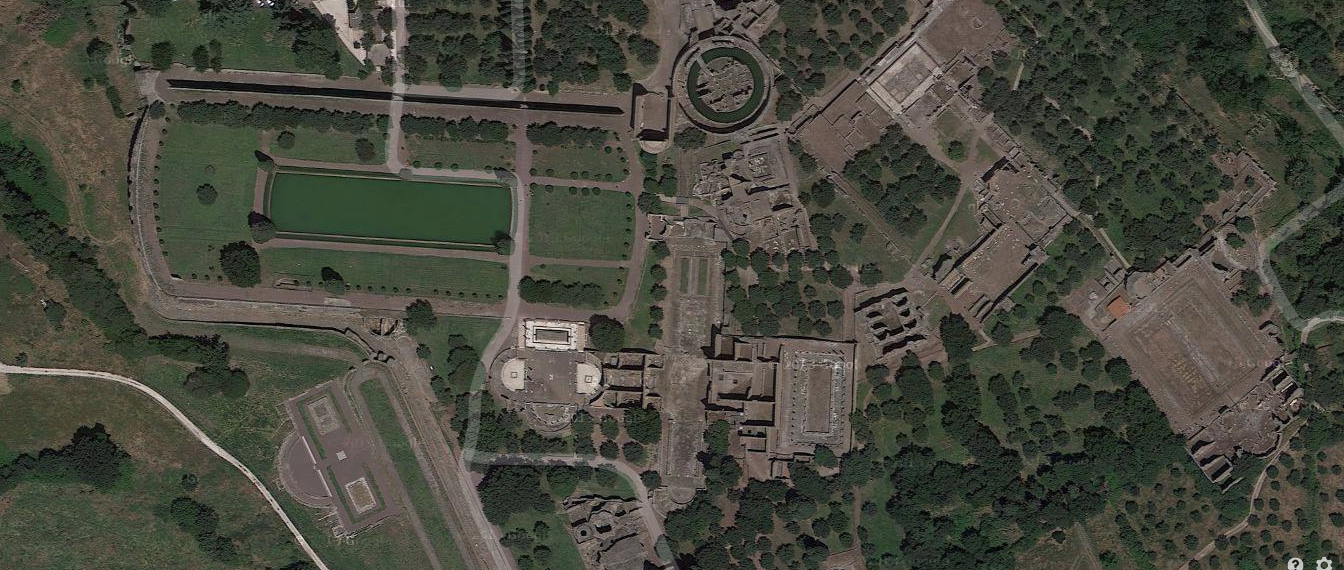

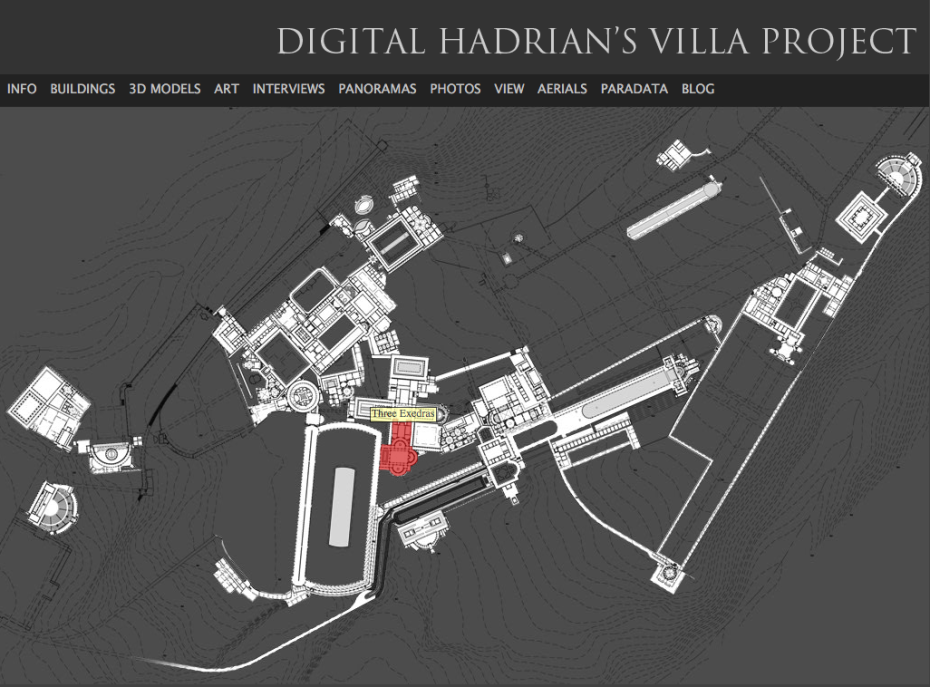

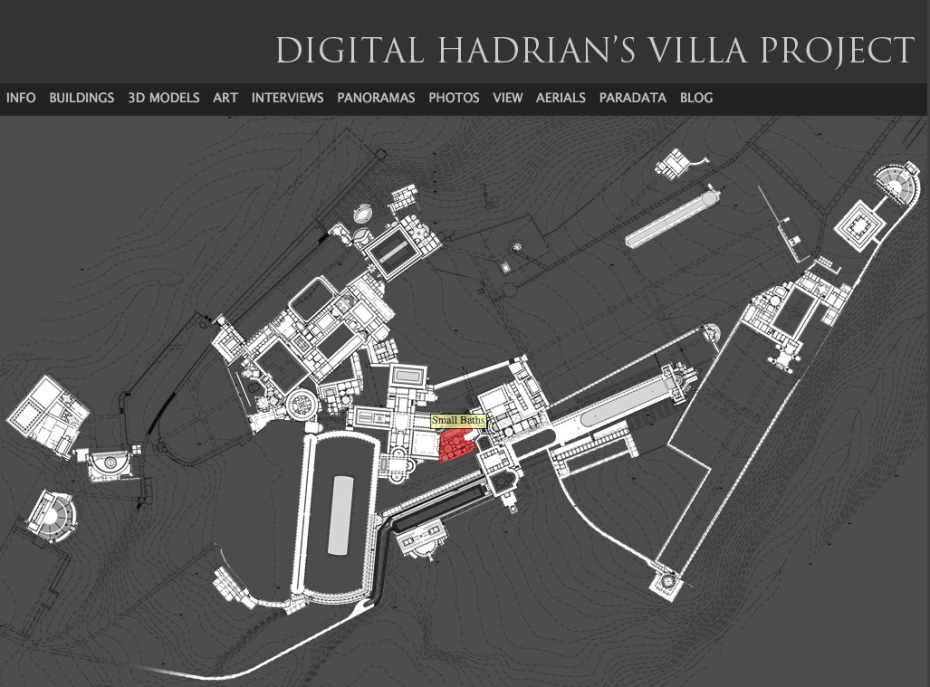

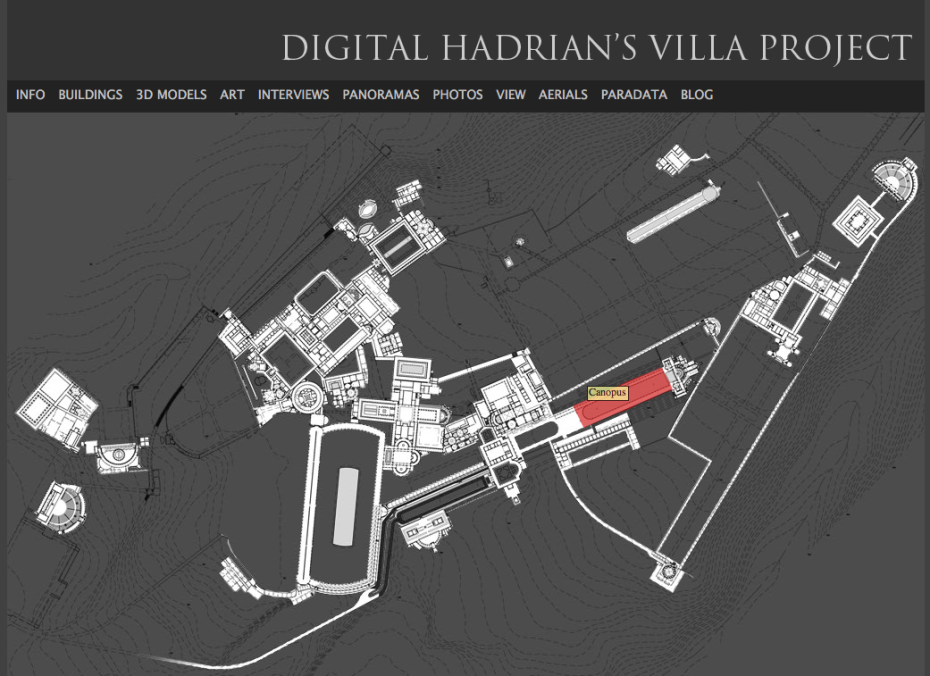

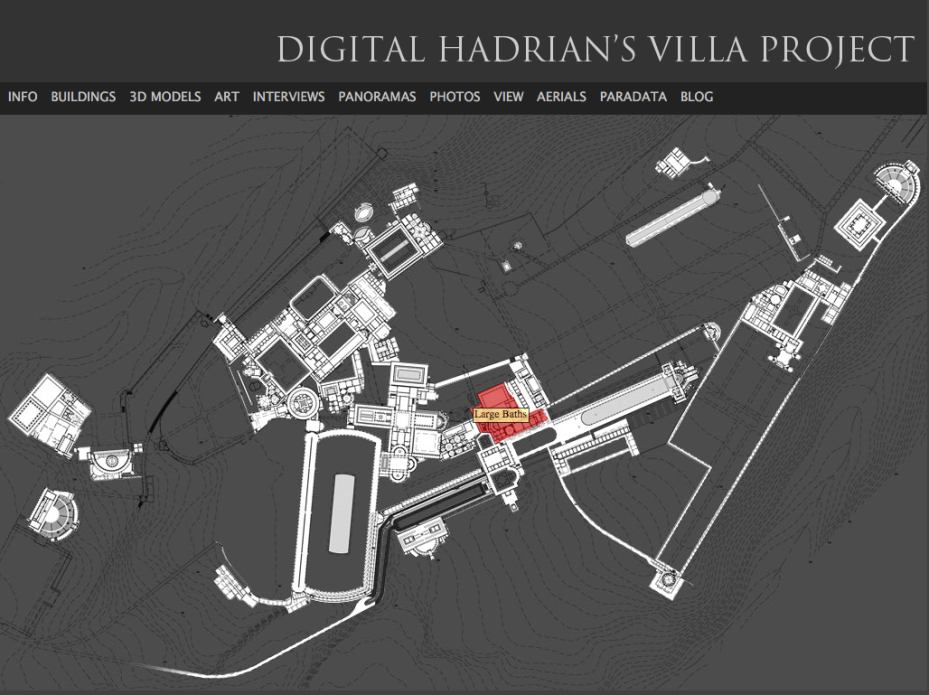

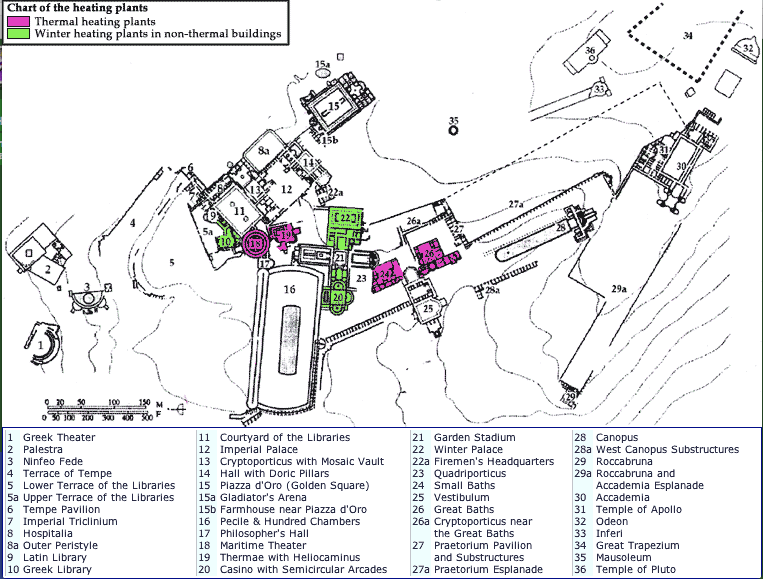

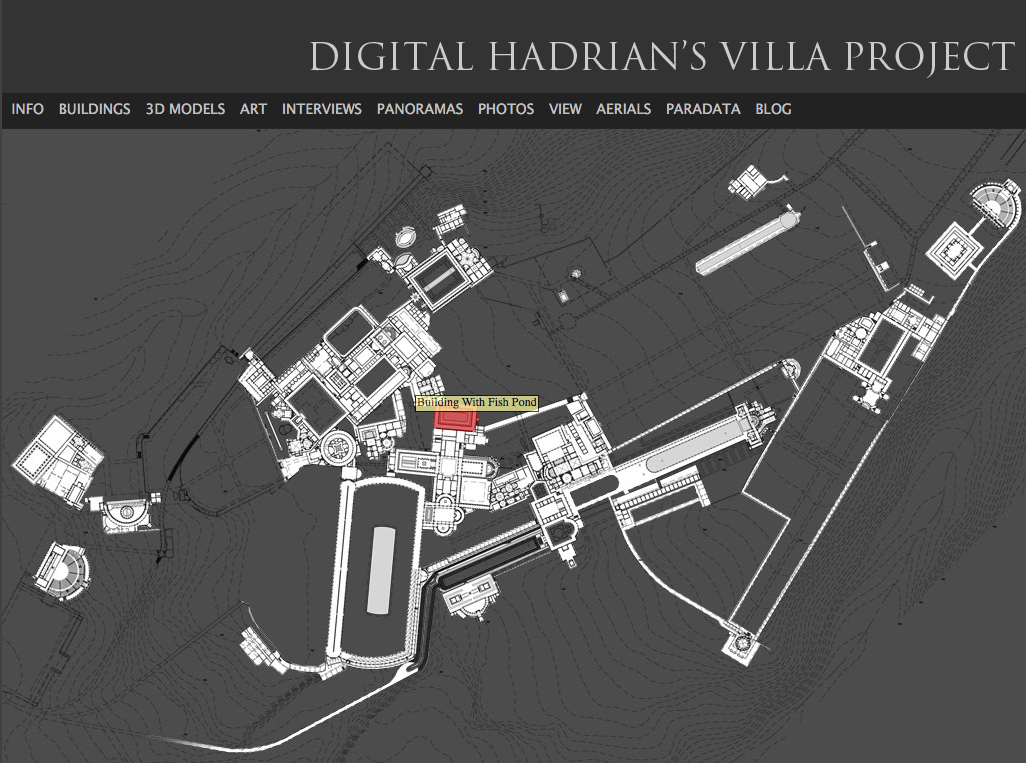

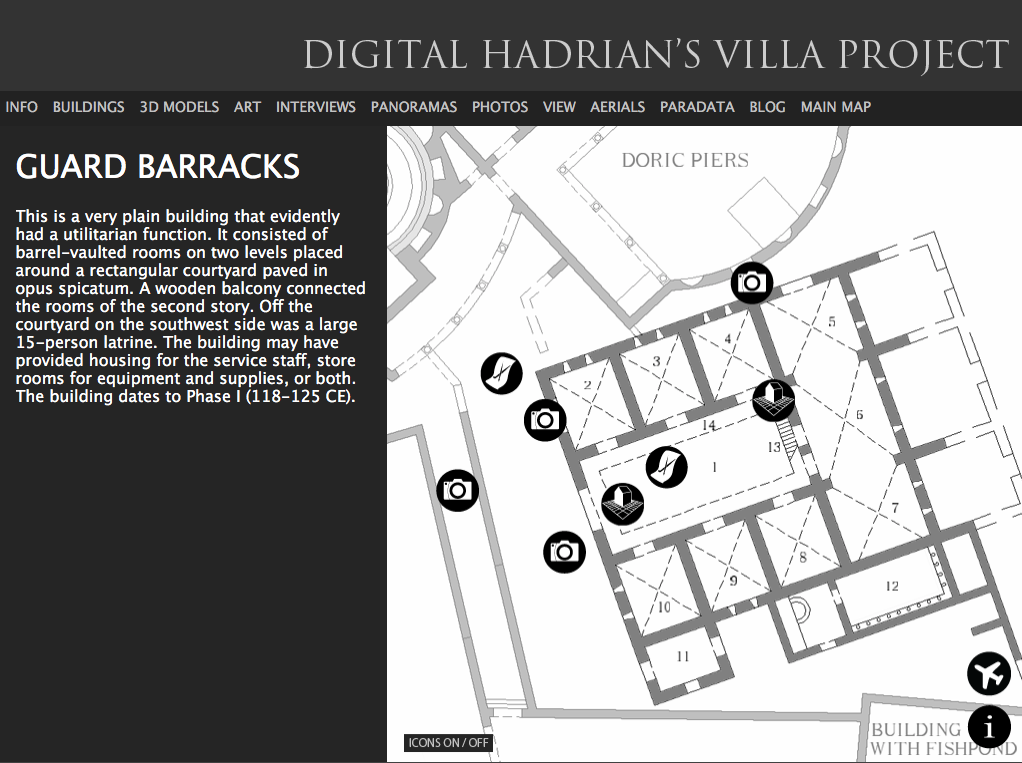

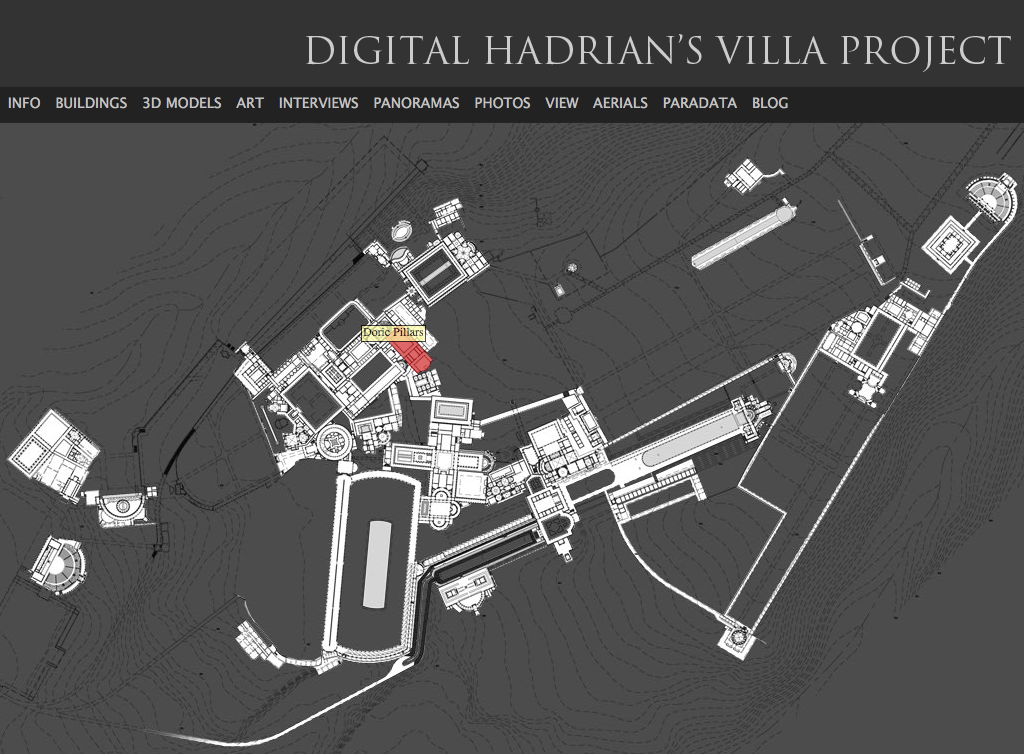

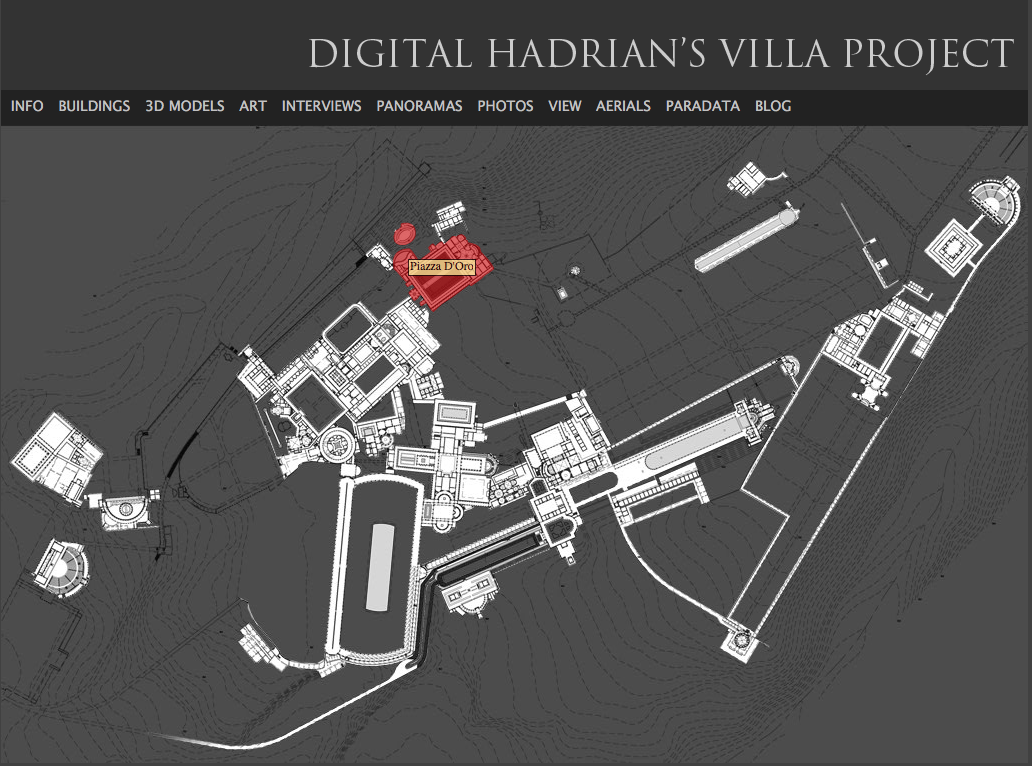

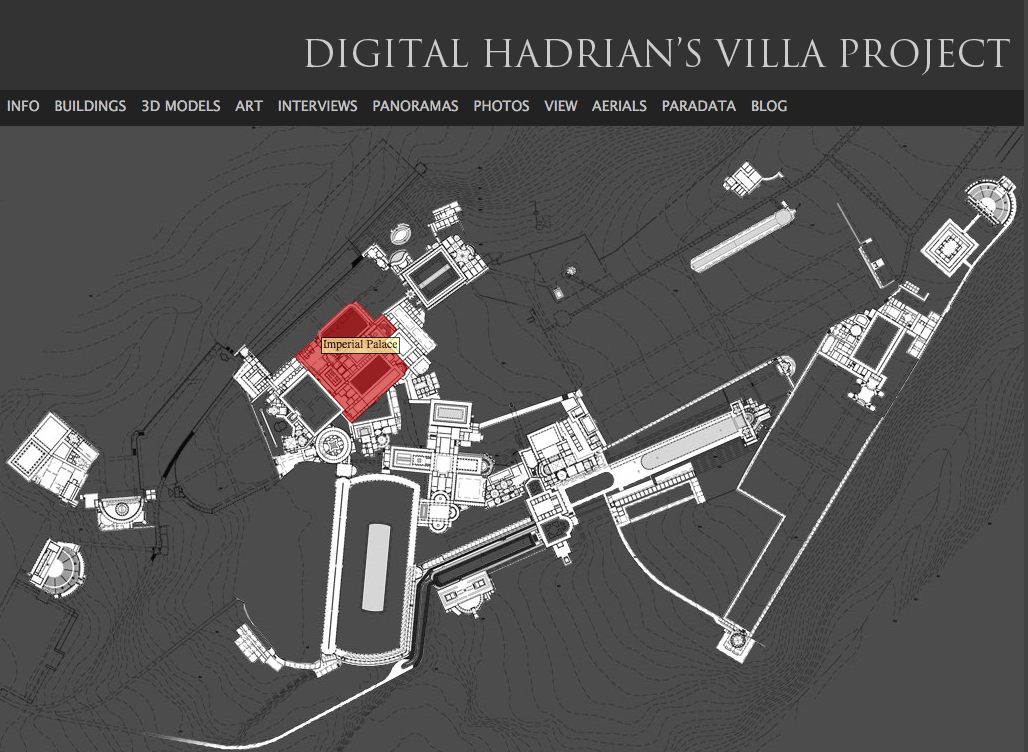

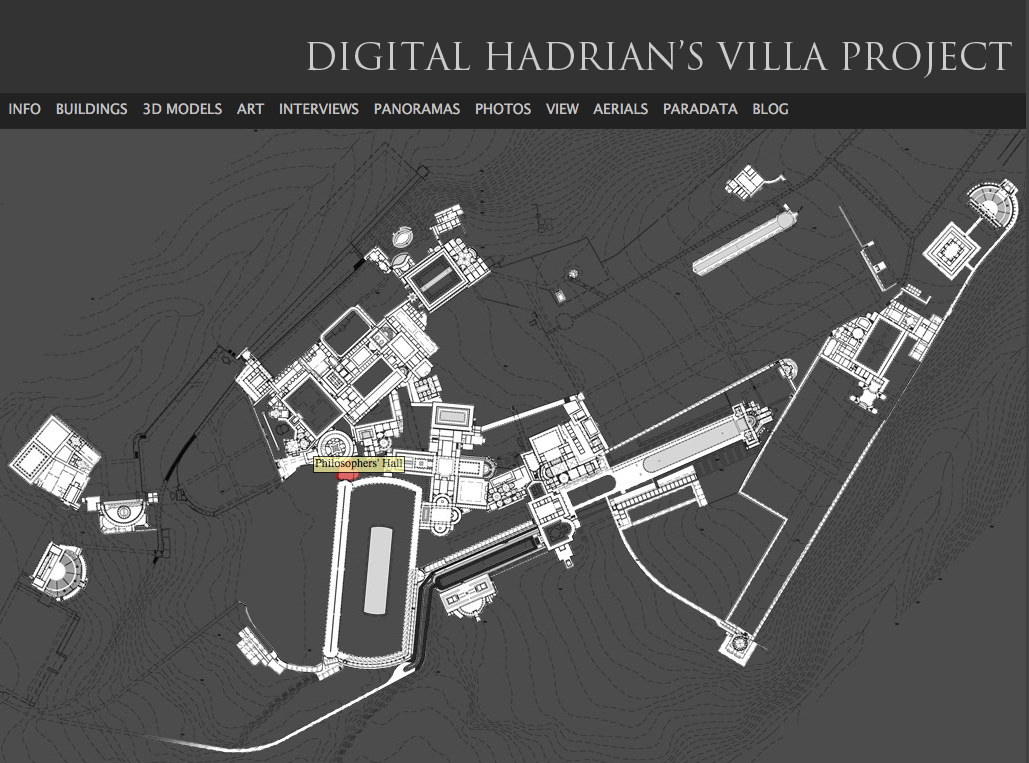

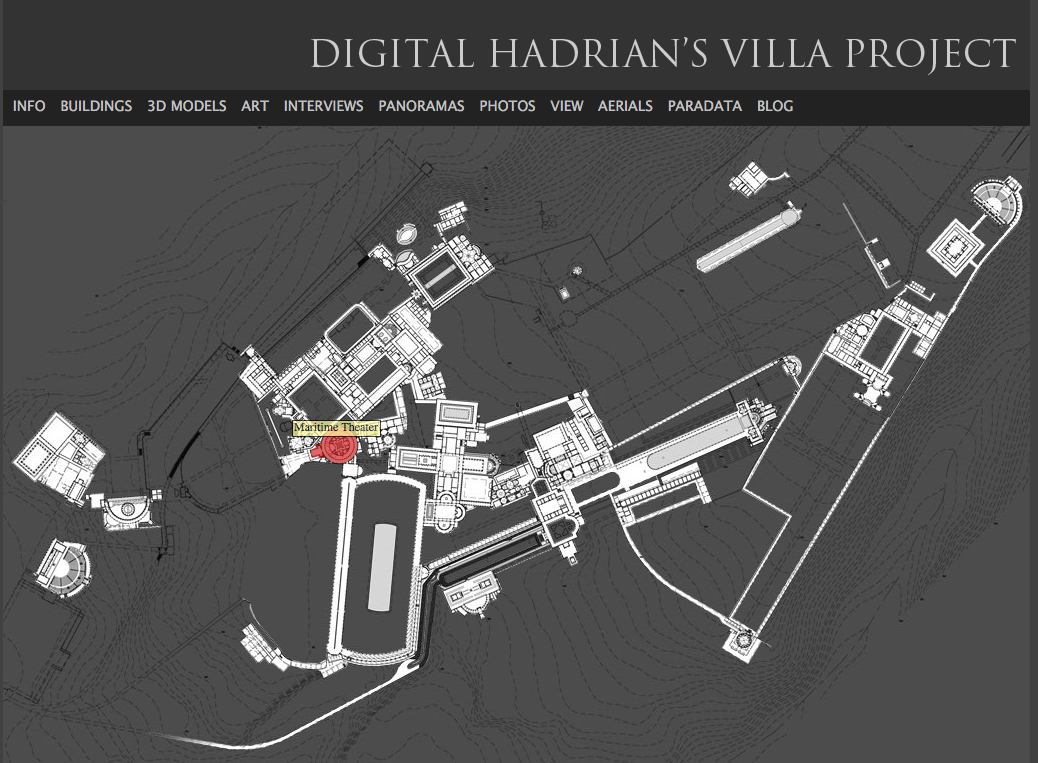

Main Map of the Excavated Areas at Hadrian’s Villa. Note: The clusters of ruins at the northernmost and southernmost ends of the site are not open to Regular Visitors. This map is shown, courtesy of Prof.Bernard Frischer, Virtual World Heritage Library, Charlottesville, VA, & the Digital Hadrian’s Villa Project.

Note: NORTH is at top of Map.

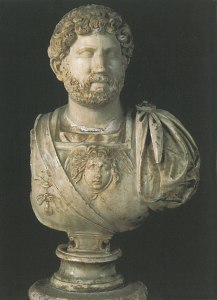

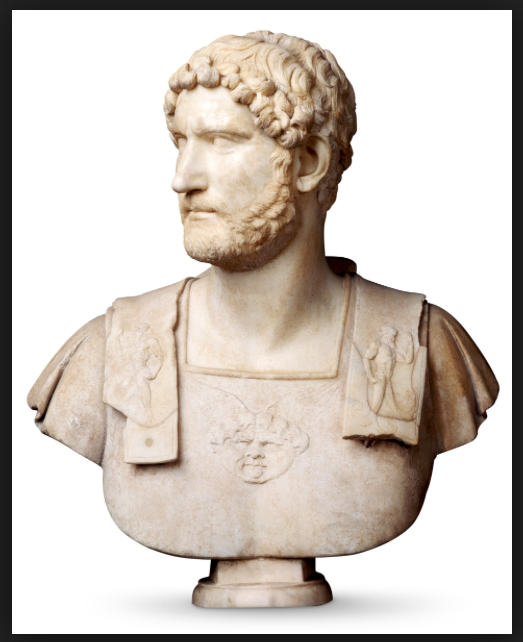

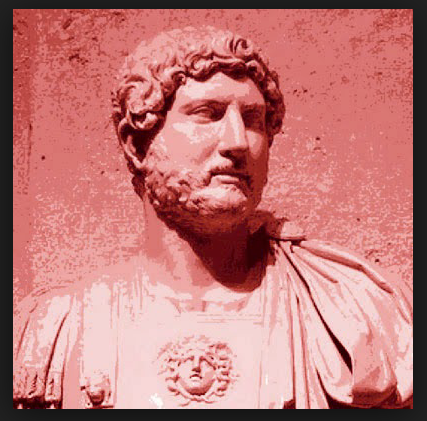

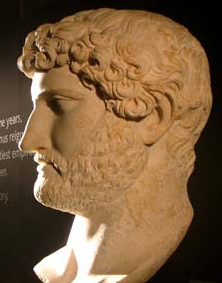

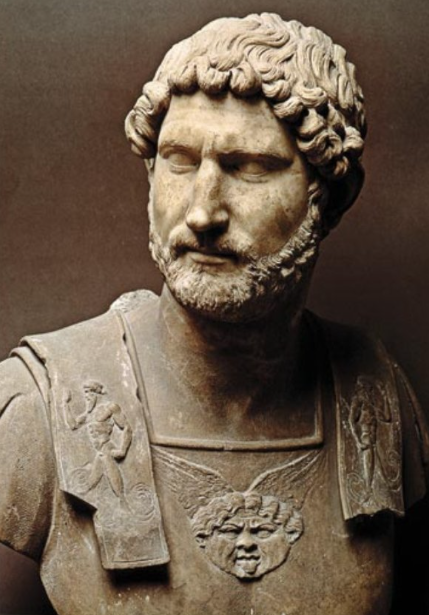

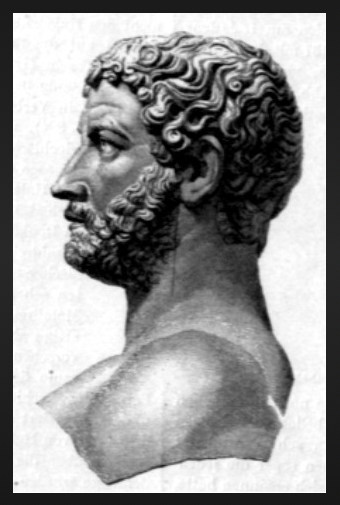

Our visit to Villa Adriana (Hadrian’s Villa) must begin with a super-compressed biography of the Emperor Hadrian, who, we will discover, was the Villa’s principal designer. Born near modern-day Seville, Spain, Hadrian was adopted by the Emperor Trajan, and upon Trajan’s death, became his successor.

Hadrian’s contemporaries described him as “prodigious and avaricious, tolerant and irascible, very approachable to common people, yet often touchy and fickle with his friends.” A true polymath, Hadrian was multi-lingual, a voracious reader, a seasoned military commander and an incessant and curious traveler. Being well-versed in mathematics, geometry, and art also made Hadrian a superbly-qualified architect. Hadrian is known as one of the “Five Good Emperors,” all of whom were adopted by their Predecessors (…yet another strong argument against

blood-relative-nepotism). In 100 AD Hadrian made a politically-expedient marriage with a daughter of Trajan’s niece: thereafter both Hadrian and his long-suffering wife Vibia Sabina, equally miserable in their union, did as much as possible to avoid each other. Hadrian actually proclaimed that, had he been a common citizen, he would have sought a divorce (and I’m sure his wife would have agreed).

In 118 AD, the Emperor Hadrian, then 42 years old, literally controlled most his Known World, and could thus have chosen any site for his country retreat and imperial palace. Thanks to the methodical Roman brick-makers, who imprinted their bricks with dates of manufacture, archaeologists are certain that construction of Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli commenced in 118 AD.

The Roman Empire in 125AD Under the Rule of Hadrian.

Per historian Christopher Kelly: “Then the empire stretched from

Hadrian’s Wall in drizzle-soaked northern England to the sun-baked banks of the Euphrates in Syria; from the great Rhine-Danube river system, which snaked across the fertile flat lands of

Europe from the Low Countries to the Black Sea; to the rich plains of the North African coast and the luxuriant gash of the Nile Valley

in Egypt. The empire completely circled the Mediterranean…referred to by its conquerors as MARE NOSTRUM—Our Sea.”

Tivoli — its most densely-built section clinging to the steep western slopes of the southernmost range of the Sabine Hills — is separated from Rome by the Campagna, an expanse of low-lying agricultural land which stretches over more than 800 square miles.

[Note: Inevitably, the Campagna’s beauty was, in the mid- 20th century, largely obliterated by urban sprawl. Today, after leaving the main highway and heading uphill towards Tivoli, one drives past used car lots, stone yards and quarries, poorly-built apartment complexes, and convenience stores: near-absolute ugliness, which causes the first-time Visitor to wonder what she’s doing there.]

The higher reaches of Tivoli are thought to have been settled as early as the 13th century BC. From Etruscan times the town was the seat of pagan sibyls … women who functioned as oracles, by divine will.

In 338 BC, the Romans, having conquered Tivoli’s Etruscan rulers (who had previously been independent allies of Rome, but who’d impractically switched their allegiance to the Gauls), absorbed the region into their Republic, and in the 2nd century BC built temples above Tivoli’s dramatic waterfalls to honor their Tiburtine Sibyl (who is said to have prophesized the birth of Christ). The area’s fresh air and abundant waters immediately beguiled wealthy Romans, who gravitated to the higher slopes of the Hills, where they built lavish villas. In these aeries, their occupants could escape Rome’s humid, stiflingly hot summers and periodic malarial outbreaks while, no less importantly, they temporarily absented themselves from the incessant political maneuvering which was part and parcel of maintaining one’s standing as a member of Rome’s ruling class.

Had Hadrian wanted to erect his Tivoli retreat amid, or above these villas of Rome’s wealthiest citizens (a group for whom he had no great affection), he could have done so. Instead, the Emperor chose an unprepossessing expanse of rolling land which lay between the foot of Monti Tiburtini and the Campagna’s eastern-most edge. A small Republican-era villa already occupied this spot, but the presence of this villa (which was an elegant but conventionally-built retreat … belonging to an unknown noble) could not have made this site any more desirable than the infinite number of other locations which Hadrian might have claimed. I imagine that, by building his Villa (and to call the small city that Hadrian built a “Villa” is hilariously demure) under their noses, it must have amused Hadrian that, as Rome’s elite gazed out from their own balconies, the spectacle of his Villa below would be there to constantly remind them of the Great Works of their highly-effective but not-terribly-well-loved Emperor.

For Hadrian, building on a massive scale was a routine occurrence.

In 122 AD, he ordered construction to begin on Hadrian’s Wall, a militarized barrier which spanned the entire 73 miles of the narrowest portion of northern England: west to east, from the Irish Sea to the North Sea.

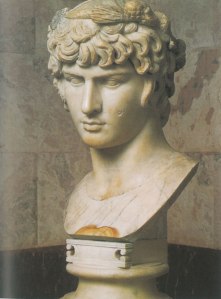

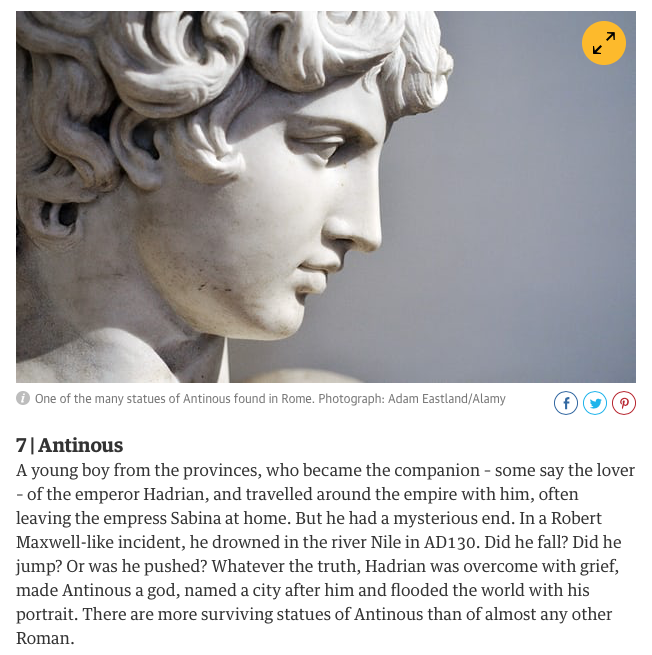

In 130 AD, in hysterical mourning over the death in Egypt of his 20-year-old inamorato, Antinous …

Antinous: Beloved of the Emperor Hadrian.

In 122 AD, during a tour of northwestern Asia Minor, Hadrian became captivated by a beautiful boy, who was only 12 years old.

For the next 8 years, Antinous was Hadrian’s companion. Antionus’ actual age is approximate, but all agree that he was still a child, when Hadrian –claimed/acquired?– him.

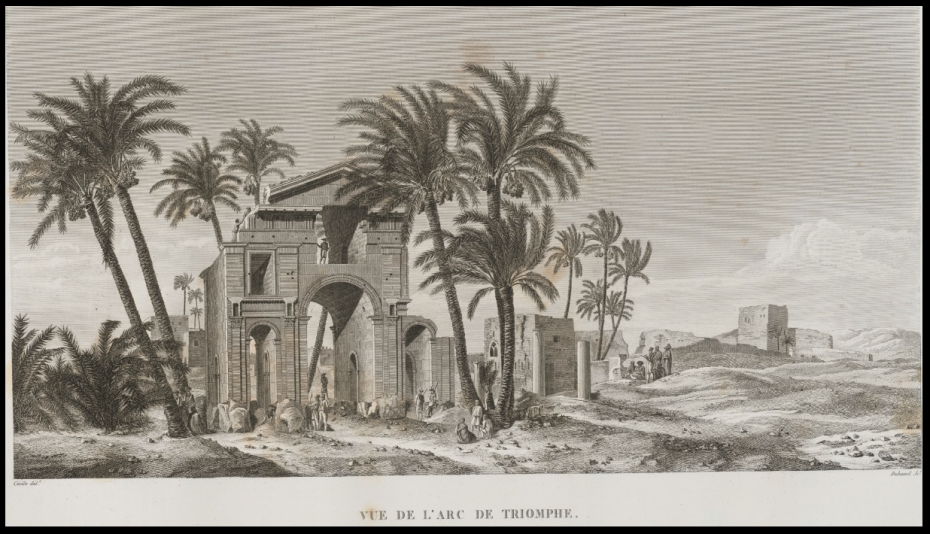

… Hadrian erected what is likely the largest ancient city ever to built from scratch: in no time, Antinoopolis (named to honor his lost love … who he also deified) appeared on the banks of the Nile, close to the place where Antinous had drowned (under mysterious circumstances).

Antinoopolis:Ruins as drawn in the 1800s. Little, apart from marks of its typically-Roman layout of streets which were built on a grid-plan, remains of Antinoopolis. This city is thought to have been about 1 ½ miles long by a half mile wide.

And so, by situating his Villa by a vast plain, the scope of Hadrian’s built creation at Tivoli was able to range far and wide. On this site without geographic boundaries, the Emperor’s ego, imagination, and capacity for architectural invention ( luxuriantly-funded by his well-stuffed Treasury ) continually expanded, for the remaining 20 years of his life. Construction at the Villa rarely ceased as Hadrian came and went: he dominated his Empire by traveling to its farthest reaches. In every different culture encountered during his journeys, Hadrian absorbed fresh ideas about how to form buildings, while he also broadened his tastes in art. At the Villa we see an amalgamation of the Emperor’s travel impressions, but those impressions are not literal.

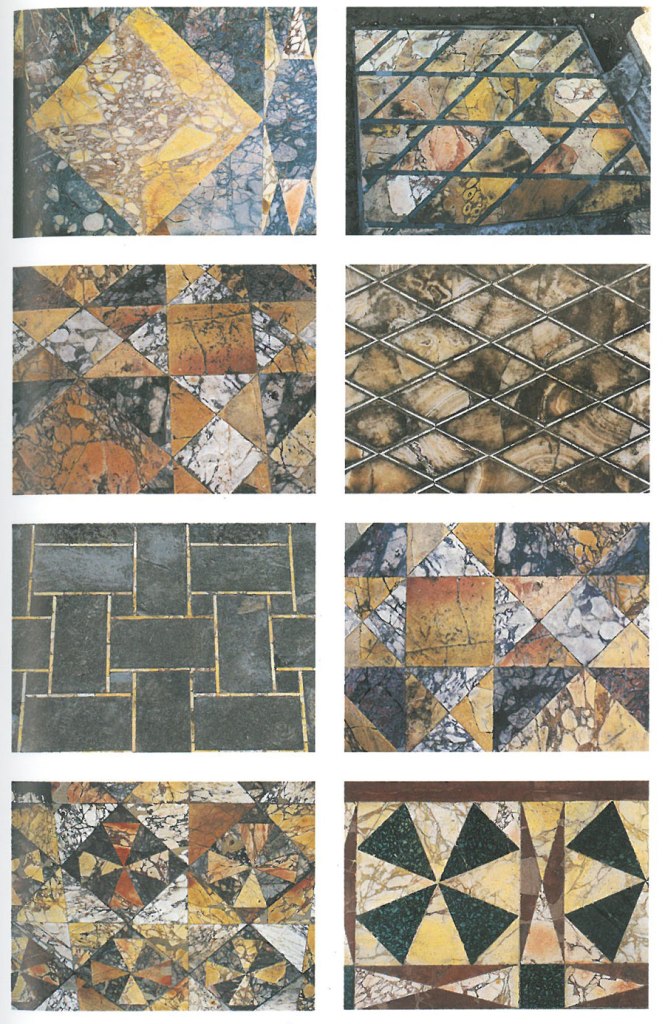

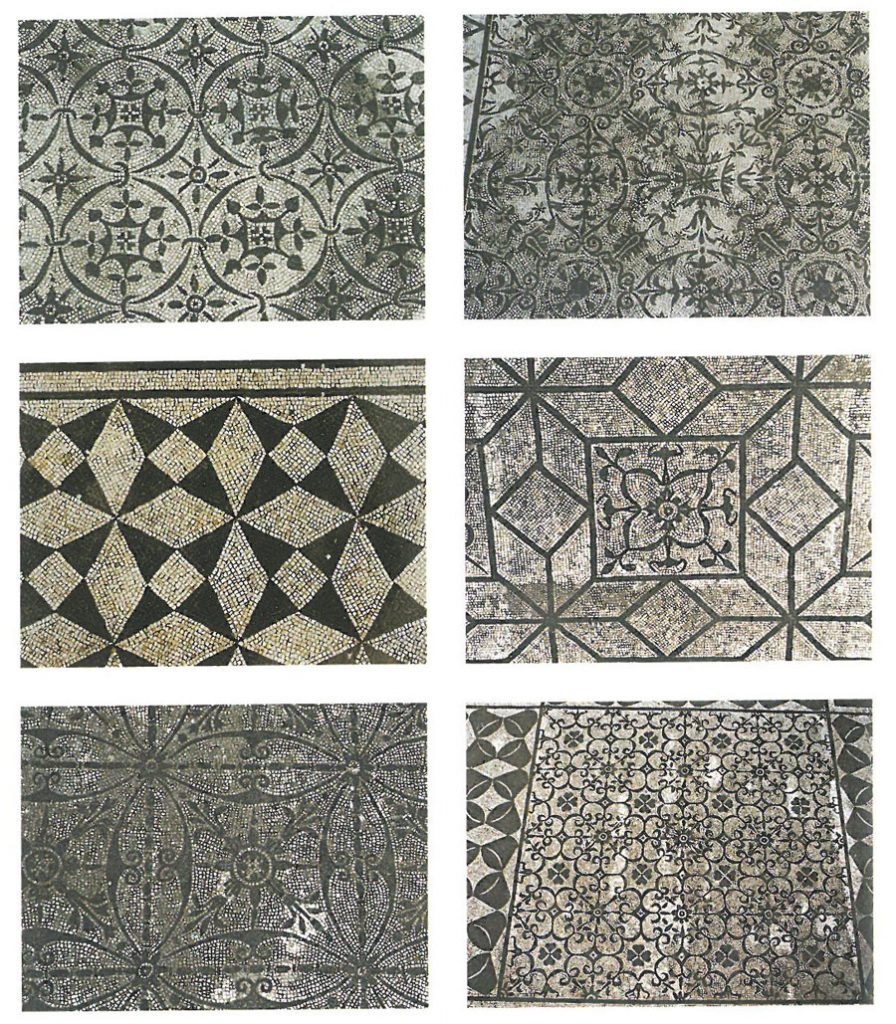

Hadrian’s Villa was eventually composed of at least 900 rooms and corridors (and these are only those spaces which archaeologists have identified, to date), where fragmentary evidence shows that most surfaces were vividly decorated with the best marbles and most precious stones (the bulk tonnage of which in later times, was scavenged, and reused to build other Roman pleasure-palaces);

Decorative Fragments, still in-situ,

at Hadrian’s Villa. Image courtesy of Soprintendenza per i Beni

Archeologici del Lazio

….of courtyards and gardens that were decorated with Hadrian’s eclectic collection of statuary accumulated during his years of travel throughout the Empire (many of those pieces now housed in museums across the World, or at the High-Renaissance mountainside water gardens of nearby Villa d’Este—which I’ll write about in Tivoli: Part Two);

…and nearly every corner of the Villa was animated by hundreds of water features (given movement by at least 100 hydraulic installations). All those who lived and worked in the labyrinth of Hadrian’s Villa must have been serenaded at every turn by a liquid soundtrack of the varied sounds of Water in Motion.

But the Villa that we encounter in the 21st century is only a whisper of Itself. We find a drab and dusty maze of rock: 98 acres of partially excavated ruins which have been baked dry by nearly 2000 scorching summers; a landscape where a monochromatic assemblage of brick and architectural fragments litters the ground; a stage set where the silhouettes of collapsed vaults frame views of turquoise skies; a surreal setting where we can walk inside a Piranesi-etching.

Hadrian’s Villa: The Large Baths. Etching by Giovanni Battista Piranesi, mid 1700s. Of all of the artists who studied the ruins at Hadrian’s Villa, Piranesi made the most accurate records of what he saw.

For the untutored Visitor, only the shattered skeleton of Hadrian’s imperial residence in Tivoli is apparent. What we encounter today is that which was never meant to be seen: the dun-colored, muscular underpinnings of Roman walls, with portions of their brick and mortar still surprisingly intact. Only if we’ve done a bit of homework can we know the surfaces of Hadrian’s Villa had been finished with veneers of the rarest marble or decorated with finely-detailed mosaics. The Villa was a riot of color and texture and SHEEN, even in its subterranean service corridors.

If we look more closely at the footings (and plans) of the Villa’s walls, we begin to see endless iterations of circles and squares. Hadrian (who had final say on what, and how, things got built) celebrated the geometries of Classical Greek Form, but also turned those conventions inside out. And, like a True Roman, he gave special attention to his domed ceilings. But he also went further afield: with complexity and audacity, he modeled and connected structures in never-before-seen ways. And contrary to the Roman way of orchestrating large spaces with grids, Hadrian’s Villa – in essence his imperial City — has no primary focal point, no central gathering place, and no organizing streets. The Villa’s chains of structures sprawl every which way across Tivoli’s rolling lowlands; the buildings all positioned in deference to the lay of the land, and subservient to the angles of the sun, and to the paths of prevailing winds.

Visitors to Hadrian’s Villa, especially those who are there for the first time, must grip their site-maps and optimistically begin their long trudge uphill from the Visitors’ Center toward the archaeological site.

This is the map on the Visitors’Brochure, which shows what the central area of the site

may have looked like, during Hadrian’s time.

And, also on the Visitors’ Brochure is a map of the ruins, many of which are off-limits, on any given day.

But after prolonged meandering, especially within the central portions of the ruins, the day-tripper inevitably becomes less certain of where he is. Hadrian, who laid the whole place out to suit his needs and whims, has, by confounding and disorienting us, authoritatively maintained his upper hand, while keeping the Mystery of his Motives intact. In the mountain of research I’ve done about Hadrian, I’ve often seen him described as a “frustrated architect.” It takes but a single visit to his creation in Tivoli to call this label ridiculous: here was a man who designed and built as much as he damn well pleased, for most of his adult life.

To truly understand the Villa, we must be aware that the network of waterways — the most critical piece of Hadrian’s design and the Villa’s primary, unifying element and circulatory system — is, apart from two large basins (at the Pecile, and the Canopus) long gone. As has often been said, the Romans loved anything that splashed, and at Tivoli Hadrian expressed this love in fountains, nymphaea, grottoes, waterfalls and pools; in overhead channels, underground tunnels and cisterns ; in bath complexes, lavatories and steam-heated rooms; in systems for the irrigation of his orchards, gardens and outlying fields.

For the Ignorant and Passive Visitor, a day at Hadrian’s Villa will be hot, perplexing, and ultimately exhausting. For the Prepared and Engaged Visitor, a day at the Villa will be hot, stimulating, and ultimately creative. [“Hot” being a constant, if you

visit from May through October.]

Thus, for a visit to Hadrian’s Villa to be even partially rewarding, one MUST have done some preparatory reading about the History of the Place. And after having done some research, one must next rev up one’s imagination, and try to visualize an omnipresence of water, in this landscape which is now mostly dry.

And so, if we consider that the Villa’s essential feature was Every-Where-Flowing-Water, we discover that, after all, there’d been perfect method in Hadrian’s madness… in his choice of this not-exquisite stretch of land as the setting for the jigsaw puzzle of buildings and waterways which would become his Masterwork.

The canny Emperor had chosen a gently-sloping stretch of land where the natural supply of water was gloriously abundant.

While you study the site maps which follow, please remember that the highest ground is at the Southern end of the site, with the lowest ground at the Northern end.

As William L.MacDonald and John A.Pinto have described in HADRIAN’S VILLA AND ITS LEGACY (published in 1995, by Yale University Press):

“Hadrian’s Villa occupies a low plain composed of tufa stone, at the foot of Monti Tiburtini; bordered by two streams (Acqua Ferrata to the east, Risicoli to the west) which unite into a single channel that feeds into the Aniene river…where the via Tiburtina crosses the river as it climbs toward Tivoli. In order to supervise the construction of this grandiose complex, Hadrian decided to move his official residence

[away from the capital in Rome]. The Villa, well connected

[by roadways] and very close to Rome, could also be approached by means of the Aniene river [which was] navigable at the time. The area hosted numerous quarries from which the Romans extracted prime building material: travertine (used in the lower portions of the Villa’s structures), lime from limestone pozzolana (a type of sand), and tufa…and was also the passageway for the four principal aqueducts that led to Rome.”

“Indications of a hundred-odd hydraulic installations survive, but although their technology is mostly well understood, Roman artistic and atmospheric uses of water are not.”

[NQ’s Note: nearly a quarter of a century has passed since the publication of MacDonald & Pinto’s extremely useful book, and continuing archaeological explorations have clarified many of these questions about the Roman uses of water, for various effects.]

Now, still more per MacDonald & Pinto:

“One thing, however, is certain: artfully shaped earth, bearing waterworks and planting and punctuated with garden pavilions and stone ornament, provided from viewpoints both indoors and out, are statements of the Villa’s cultural context.”

“The hydraulic regime was complex and sophisticated. Water entered from the southeast [the highest point] and was divided repeatedly to form a tapestry of fresh water across the entire Villa.The flow was regulated by cisterns and efficient plumbing. Fountains and grottoes of various sizes and types, bath buildings, ornamental pools, irrigation systems, and human and animal requirements were all accommodated; the used water discharged continually through underground channels leading to the Aniene [river].”

“The [water] pressure required by jets and other dramatic effects was ensured both by the superior elevation of the incoming water supply and by the strategically located cisterns, as well as by efficient piping. The generally descending nature of the terrain suggests that water-lifting devices were probably unnecessary.”

So, Reader: be awed at what these Ancient Romans began to build, in 118 AD. At Hadrian’s Villa we everywhere see evidence of an architectural designer who mastered traditionally-styled building methods, but who then also moved beyond these norms of fashion. We gain inklings of how the Emperor and his clever engineers transformed their watery fantasies into reality. And never forget that all of these marvels were constructed by legions of slaves, who, equipped with nothing more than hand-tools, and with only oxen and carts to move dirt and transport heavy materials, toiled for the next twenty years to make Hadrian’s Villa a true wonder of the Ancient World.

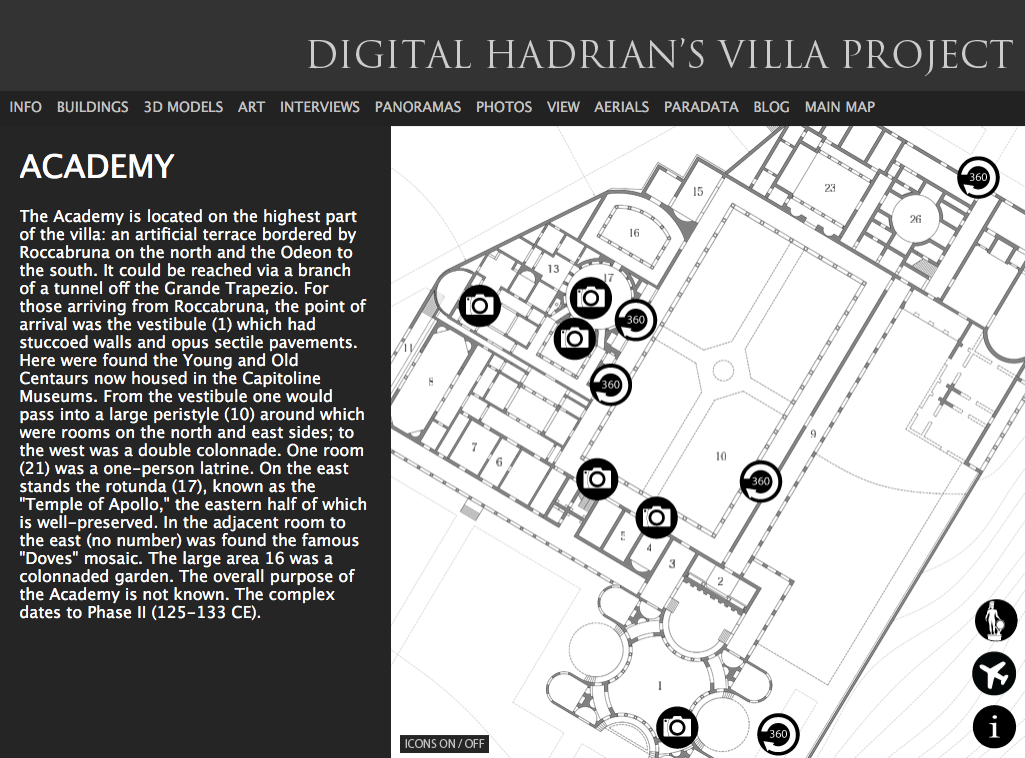

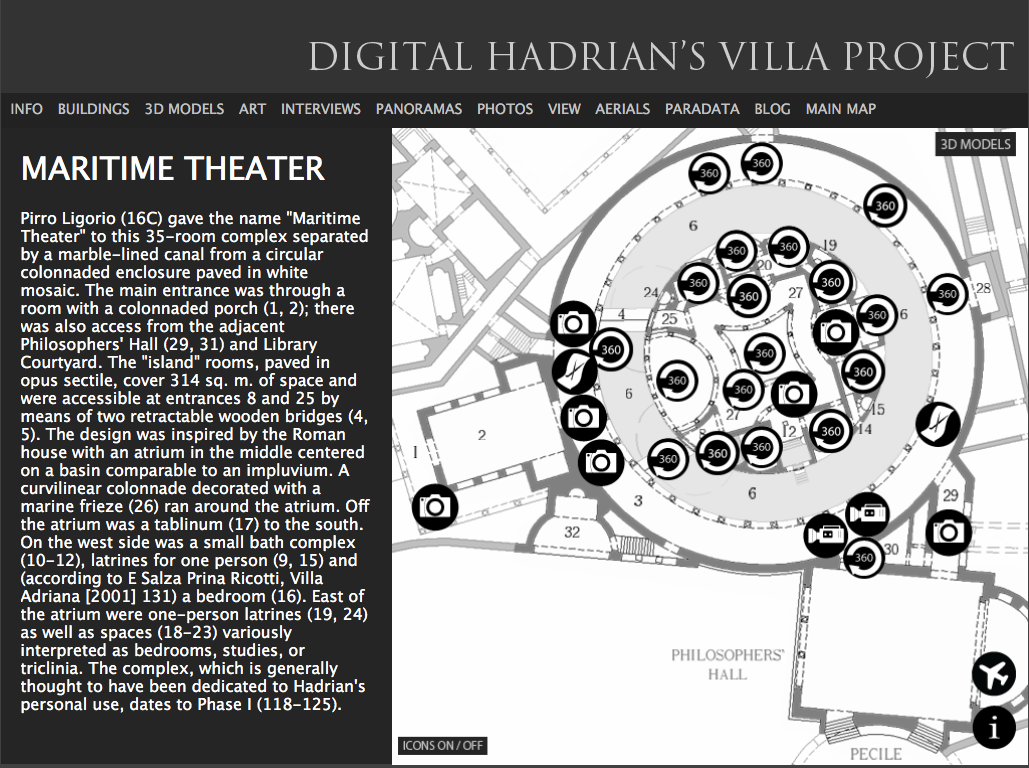

After assembling a respectable library about Hadrian’s Villa, and making multiple trips to Tivoli, I realized that despite all of my books and monographs, and those site visits and my hundreds of photographs, my brain still ACHED as I tried to weave all of that information (often contradictory information … ) into a coherent whole, and then into a sensible and enjoyable Diary for Armchair Travelers … and hopefully also a Diary which wouldn’t feel like there’d be a Pop Quiz To Follow. Happily, a recent web-search about the Villa led me to the Digital Hadrian’s Villa Project , which is overseen by Professor Bernard Frischer, of the Virtual World Heritage Laboratory, in Charlottesville, VA.

The Digital Hadrian’s Villa Project website is tour-de-force of mapmaking, and best suited for use by hardcore scholars who know what nuggets they’re digging for. I found their maps and 3D renderings to be especially well-designed and helpful, and Prof. Frischer has generously allowed me to reproduce here those portions of his website which I think will add clarity to my survey to Hadrian’s Villa.

All illustrations which are shared by the

Digital Hadrian’s Villa Project will be credited with the notation: “Courtesy of DHVP”

And also, in my eleventh hour of fact-checking, I happened upon another hugely-helpful website about Hadrian’s Villa; this one

orchestrated by the scholar Marina De Franceschini, who has spent a lifetime studying the Villa.Marina’s site

( www.villa-adriana.net )

offers a treasure-trove of historical, architectural, and artistic detail.

After you’ve digested my Diary — which is meant to serve as an introduction to Villa Adriana — if you then wish to dive deeper into every historical and artistic aspect of the Villa, I recommend that you visit Marina’s site.

In my Diary, with Marina’s kind permission, I’ll reproduce some essential maps, and I’ll also include photos of the Villa’s network of tunnels (which are not open to the hoi polloi).

All illustrations which are shared by Marina De Franceschini will be credited with the notation:

“Courtesy of Marina De Franceschini”

Please join me now, for a tour of Hadrian’s Villa.

Regarding place-names of the parts of the Villa that we’ll soon visit, only one, The Canopus, is certain as being from Hadrian’s time. The other ruins on site have over the past four and half centuries been assigned their names: some of them credible and descriptive of the structures’ original purposes…but other labels fanciful or downright misleading. In 1550, after Hadrian’s Villa had suffered from 1400 years of being scavenged and then forgotten, the architect Pirro Ligorio began to explore, and to NAME areas: and many of his labels have stuck. Ligorio also made the first measured drawings of the central ruins, and his methodical excavations, along with his maps and notes, are considered the “first large-scale modern archaeological dig.”

Ligorio, who was beginning to design fantastical water gardens for Cardinal Ippolito d’Este ( which would be sited uphill and several miles away from the ruins of Hadrian’s Villa ) , went to the ruins intending to acquire as many pieces of statuary, and as much tonnage of marble, as his workers could excavate. Cardinal d’Este, who as Governor of Tivoli could lay claim to the Villa’s ruins, had hit the Jackpot, in sculpture and in building material. With treasures taken from Hadrian’s Villa, the Cardinal’s own remodeled villa, and new gardens (which I’ll show you in Part Two), would soon be so lavishly decorated as to make kings and queens covetous.

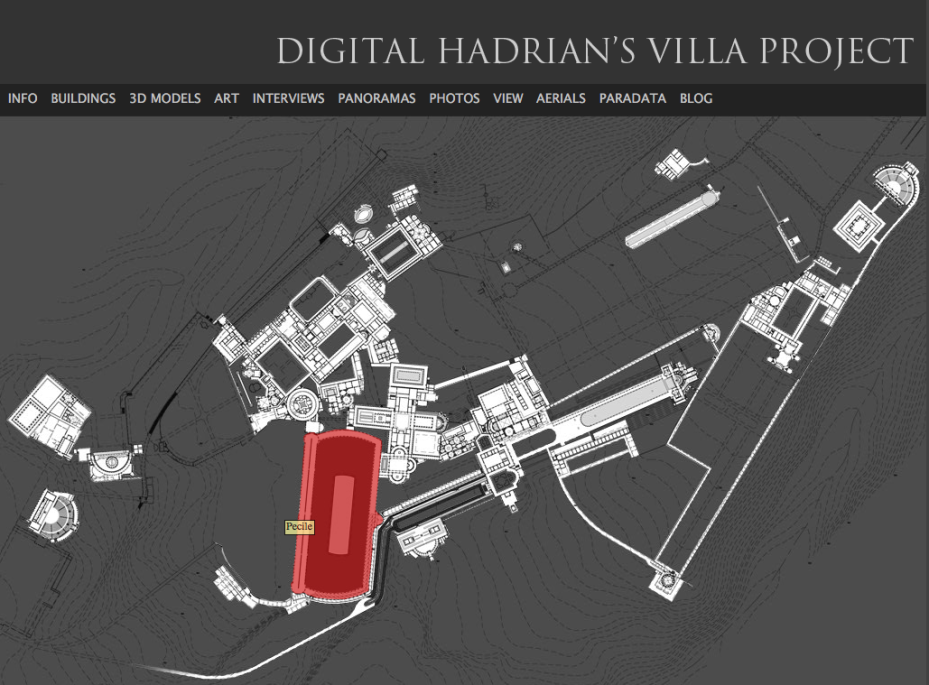

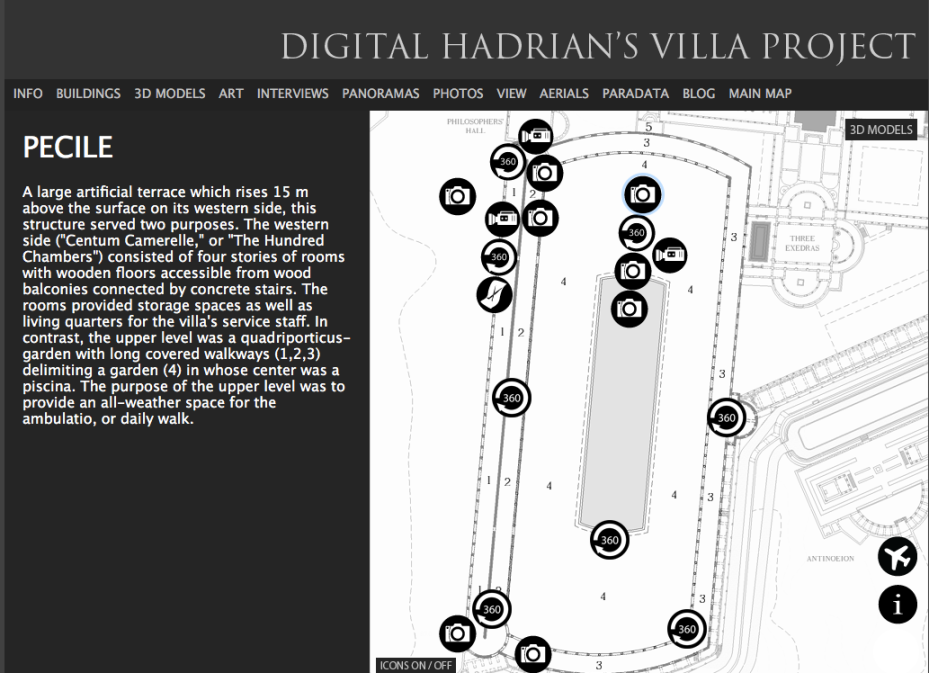

PECILE

Today’s visitors to the archaeological site enter through an opening in a massive wall, which I’ll identify as the North Wall.

Having made our way uphill, away from the crowds at the Visitors’ Center, we arrive at the North Wall of the Pecile.

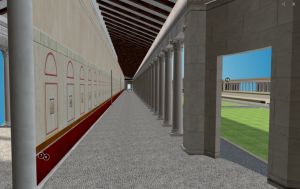

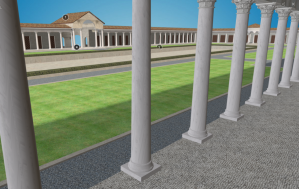

This wall, aligned from west to east, is over 29 feet tall, and is all that survives of the Pecile’s once-totally-enclosed space. The Pecile, with outer dimensions of 318 feet wide by 762 feet long, sits upon a raised terrace, which is supported by a massive understructure ( this called The Hundred Chambers & next on our itinerary ). The Pecile is centered upon a pool which is 82 feet wide by 328 feet long (called the Piscina). Interior loggias ran along the interior of all four walls, and a single exterior loggia was also built alongside the north-facing wall.

Per the historian Benedetta Adembri, in the Villa’s Guidebook:

The north wall “of the portico, constructed prior to the remainder of the complex, was intended for the after-lunch stroll, as an inscription in this area discovered during the 18th century recalls, which states that the length of the portico itself was 1450 feet…equivalent to the distance of an entire circuit around the [North] wall. The inscription continues, stating that by following the course seven times, one would have walked about two Roman miles. Therefore the length of the double portico was calculated according to the rules of a healthy walk (ambulatio) determined by doctors.”

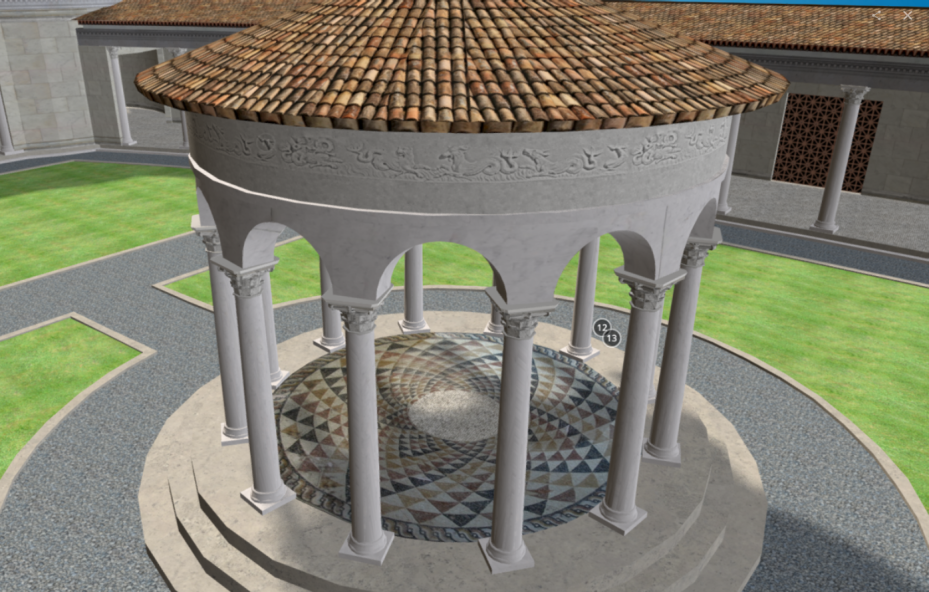

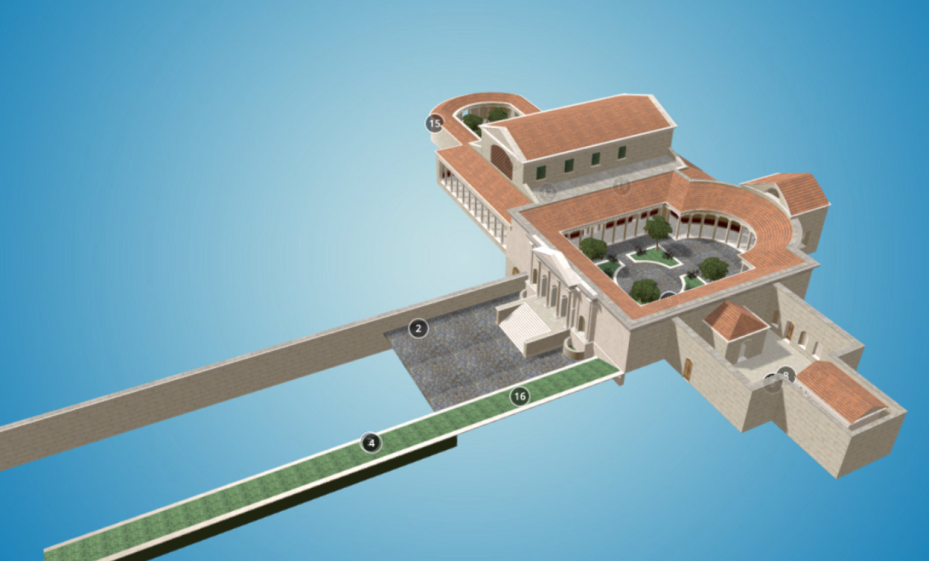

3D Rendering of the

Pecile’s North Wall Walkway. Porticos on both sides of this North Wall provided a protected route for that health-promoting, 7-times-around-the-wall walk which Roman physicians recommended. Courtesy of DHVP

“During the second phase of the Villa’s construction the short ends were added to the portico. These slightly curved porticos closed off the garden area. Unlike the current situation, where our vision is often misguided toward the inner region of the Villa and beyond the perimeter of the Pecile [toward] magnificent views of the countryside, this garden was not considered with the surrounding panorama in mind. The tall walls that enclosed the columned portico would have impeded views of the landscape and served to isolate the park around a mirror of water, providing a peaceful and relaxing atmosphere.”

3D Rendering of the Pecile’s Inner Court, with Piscina (large pool–shown here in Gray) at the center. Courtesy of DHVP

3D Rendering of the free-standing Pavilion at the east end of the Pecile’s Inner Court. Courtesy of DHVP

Ms. Adembri’s final sentence describing the original appearance of the Pecile is what today’s Visitors to the Villa should keep in mind, as they explore all of the ruins, because in Massive Walls and Endless Porticos and Hidden Gardens and Omnipresent Waterworks we find the oft-repeated parts of the gargantuan whole.

The Emperor was designing ENCLOSURES: hundreds — perhaps thousands — of them. Hadrian’s architecture was about Control. Within the confines of his vast Villa — which effectively functioned as his fortress home — he could live and deal with his subordinates in a secure environment. And the Emperor’s desire for control also extended to his interactions with nature. Here at the edge of the Campagna, he was not going to frolic in Nature-in-the-Raw. [Note: During the years of his nearly-incessant travels across the Empire, I imagine he’d done enough camping.] Instead, the views he wished to have of the wider landscape were to be framed by acres upon acres of masonry, which his army of workmen would shape to suit his insatiable appetite for the infinite possibilities of FORM. One’s exposure to sunlight—or shadow—was to be dictated by intricate combinations of roofscapes and courtyard openings.

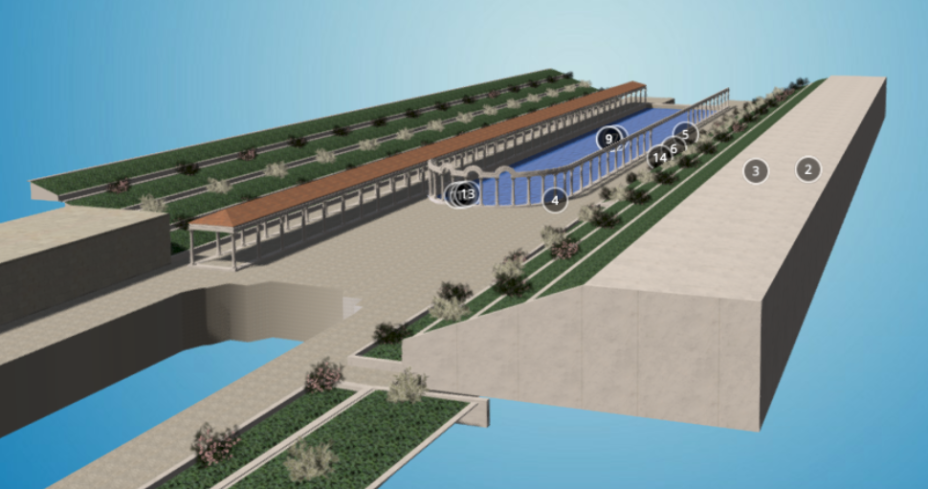

Locations of the Gardens at the Villa.

[Note: continuing exploration of the site has since revealed that two long gardens, which were not known of when this map was charted,

also ran along both sides of the artificially-made valley of the Canopus. ]

Courtesy of Marina De Franceschini

My view, from the center of the north side of the Pecile. Diagonally across the body of water is the Triple Exedra Complex.

This is Piranesi’s view of the great, North Wall in 1770, when he occupied the same spot as I did, when I looked eastward, toward the Sabine Hills. Image courtesy of Yale University Press.

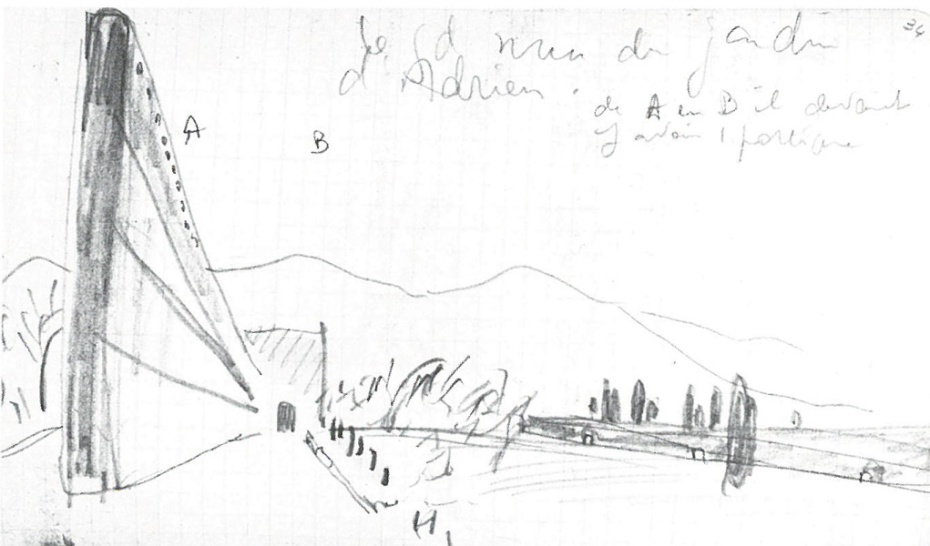

And in 1911, the young architect

Le Corbusier sketched the same view. Image courtesy of Yale University Press.

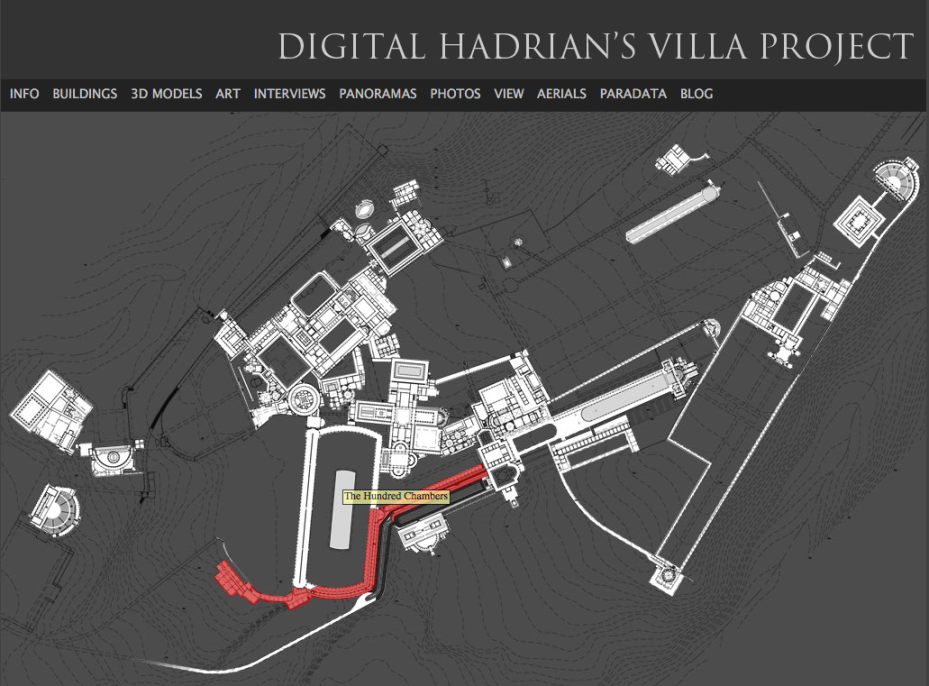

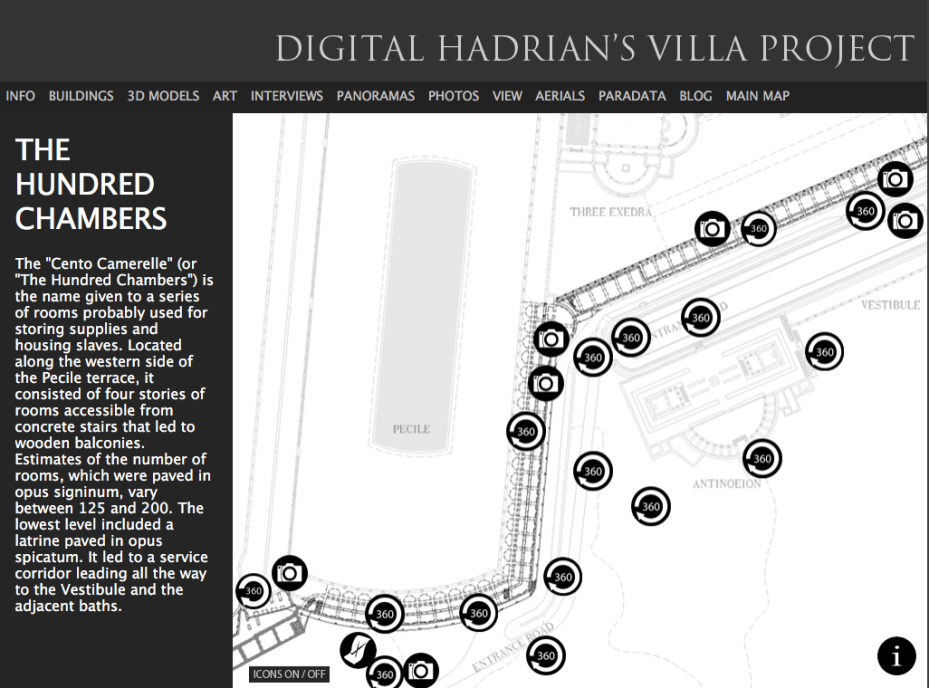

THE HUNDRED CHAMBERS

To create a flat surface for his Pecile, Hadrian’s engineers began by constructing a 50 foot high retaining wall along the western-most edge of the sloping site. The wall was pierced at regular intervals with large openings, which provided access to, along with light for, the interiors. The retaining wall was then continued below the southern edge of the Pecile, and then extended even further westward, to support the terraces adjacent to the Three Exedra Complex. Honeycombed behind the retaining walls (which, at their highest point were the outward faces of a 4-level, subterranean warren of rooms) were built at least 100 small, identically-dimensioned chambers, which had single doors onto the wooden walkways which ran directly behind the wall openings. Because of the humble nature and large number of these rooms, archaeologists have theorized that the upper 3 stories of the 100 Chambers were slave quarters. The ground-level rooms of the 100 Chambers were most likely used to store the tons of goods and produce which were needed for the care and feeding of the thousands of people who lived onsite.

Aerial view of the western elevation of the HUNDRED CHAMBERS, which are tucked beneath

the Pecile (to the left), and which are also built below the long

Promenade (extending to the right) which runs past the

Three Exedra Complex, the Small Baths, and the Large Baths.

Courtesy of DHVP

My view of the south elevation of the Hundred Chambers

(as I was standing to the west of the Three Exedras)

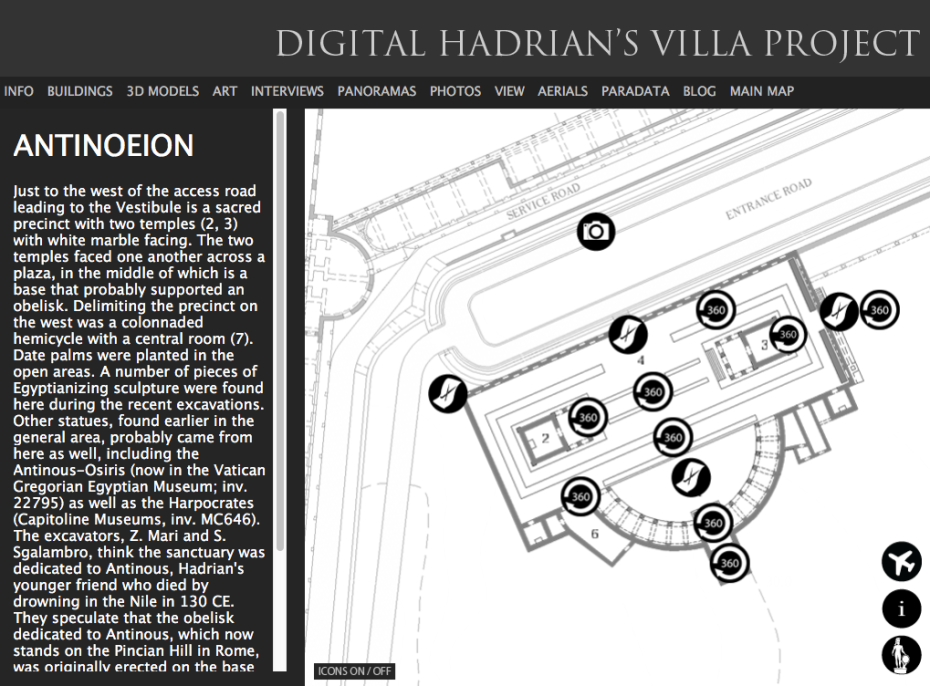

ANTINOEION

…which explains WHY, whenever you

see yet another marble statue of a beautiful young Roman, you’re

probably looking at Antinous. Image and text, courtesy of the

GUARDIAN.

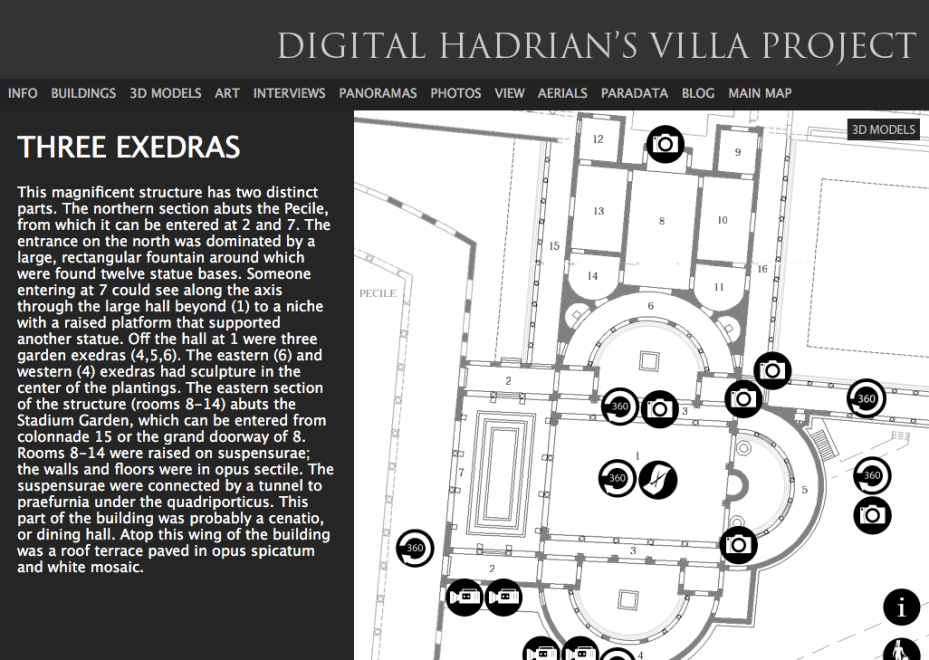

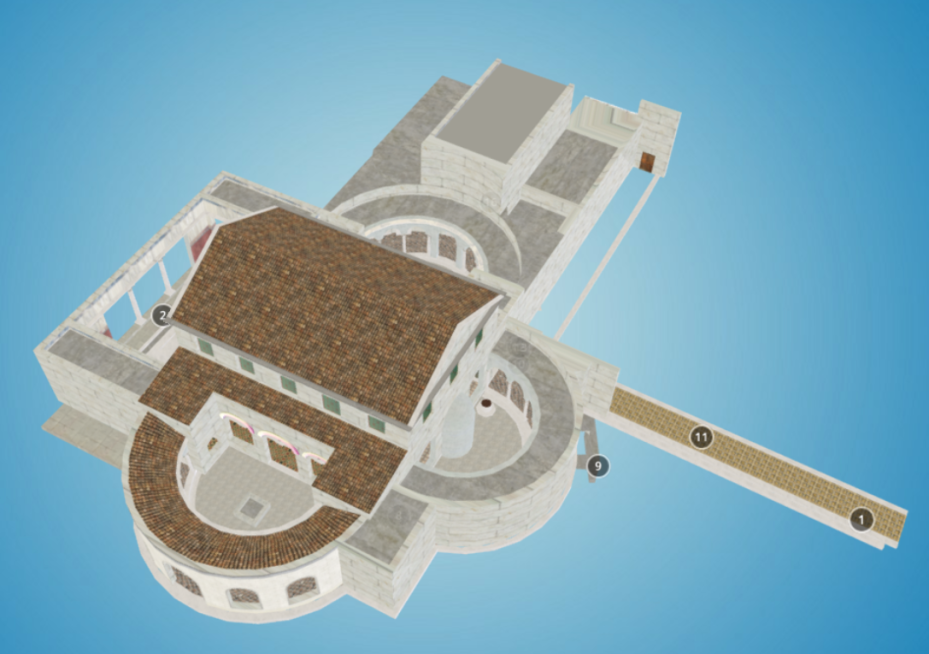

TRIPLE EXEDRA COMPLEX ( THREE EXEDRAS )

How Hadrian used this unusual complex of buildings is unknown, but its central location and obvious connection to the nearby Stadium Garden and Winter Palace indicates that this eccentric construction was of particular importance to Hadrian.

Scholars have called this section of the Villa the Three Exedras, or Triple Exedra Complex, or the Casino With Semi-Circular Arches. Exedras were halls –often partially open to the outdoors—where meetings and enlightened (it was hoped) discussion took place. Although now worn down to a mere suggestion of the original clover-shape, it’s clear that the Three Exedras—whatever they were meant for—presented a surprising and exquisite series of indoor/outdoor spaces. Seen in Plan, the obvious entrance would have been located at the north side, which abutted the Pecile. But oddly, this large rectangular atrium, which, if designed by a conventional Roman architect, would normally have been a marble-floored entry hall, was instead almost entirely filled by a pool in which fountains sprayed. Anyone tiptoeing around the perimeter of this room would certainly have gotten soaked. The Romans were great practical jokers, when it came to waterworks and their gardens (a hidden squirting-mechanism that drenched an unsuspecting passer-by was a favorite joke) and I theorize that, by making his entire atrium here into a place where dry-passage was impossible, Hadrian was having some Serious Fun. For those not delighting in the Wet Look, access to the centrally-placed Hall could be gotten through one of the three columned gardens which occupied half-circle plots, on the west, south, and east sides of the central Hall.

Aerial view of the Pecile

(to the left), the Hundred Chambers (which are built below the Pecile), with the half-moon outline of the site of the Antinoeion below the Hundred Chambers. The Exedra Complex is to the east, and above the Antinoeion (seen here on the right). Courtesy of DHVP

I ‘m walking across the space which was once the location of the large Hall, which was at the center of Triple Exedra Complex

At the left of this photo is the south side

of the fountain-filled atrium.

The west side of the Three Exedras. In the foreground: one of the Exedra’s 3 garden terraces. Each of these gardens was formed in a half-circle, and centered on a square pool. These gardens were all enclosed by columned loggias.

Detail: Passageway from the east garden of the Exedras. Beyond this is a complex of smaller rooms, which connected with the Stadium Garden, and then to the Winter Palace.

Now I’m in the south-side, half-circle garden of the Three Exedras. To the far rear, you see the great North Wall of the Pecile.

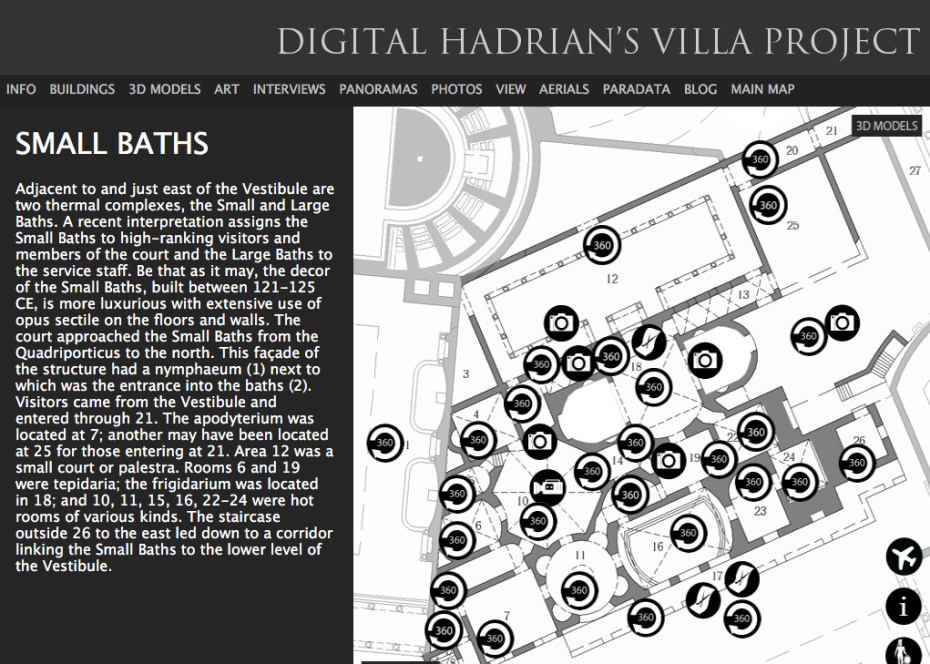

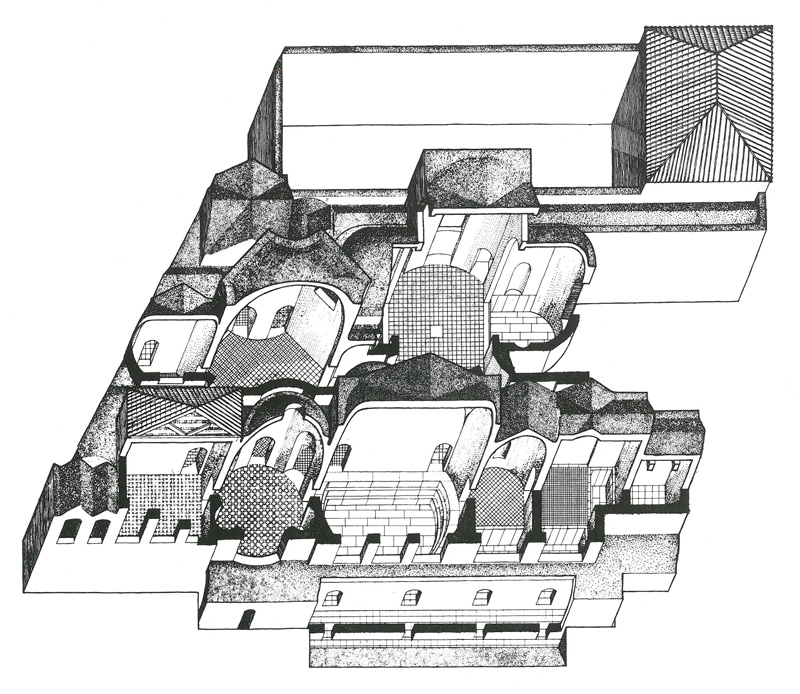

SMALL BATHS

The western side of the Small Baths. On that very hot day in mid-May, as I enjoyed the dappled light in this grove of olive trees,

Hadrian’s Villa, although in ruins, felt like a Living Place.

Fragment of a Very-Solidly-Constructed–Wall, near the Small Baths. All of this masonry would have been concealed by layers

of precious marble.

The tilework which remains at the Villa identifies the level of refinement of the people who used various buildings. The Small Baths, frequented by high-ranking personnel, were lavishly decorated with Opus Sectile Marble Floor Inlays. The red porphyry — the rare, red-purple stone that you see here — was only used in buildings which were used by

those of elevated status.

Image courtesy of Marina De Franceschini

Within the Small Baths. I’m at the southeast corner of this complex, about to enter the small outdoor courtyard (palestra), which ran along the east side of the Small Baths.

Sometimes, the most mundane details Tell the Tale. Remains of toilet facilities at Hadrian’s Villa reveal the nature of the buildings which they served. A Single Hole? Definitely the Emperor’s “Throne,” or perhaps a Pot for a Favored Friend! A Multi-Seater … but not with TOO

many holes? These were for guests and presumably the praetorian guard. And then there were those odious, hundred-foot-long latrines, which were used by slaves and soldiers.

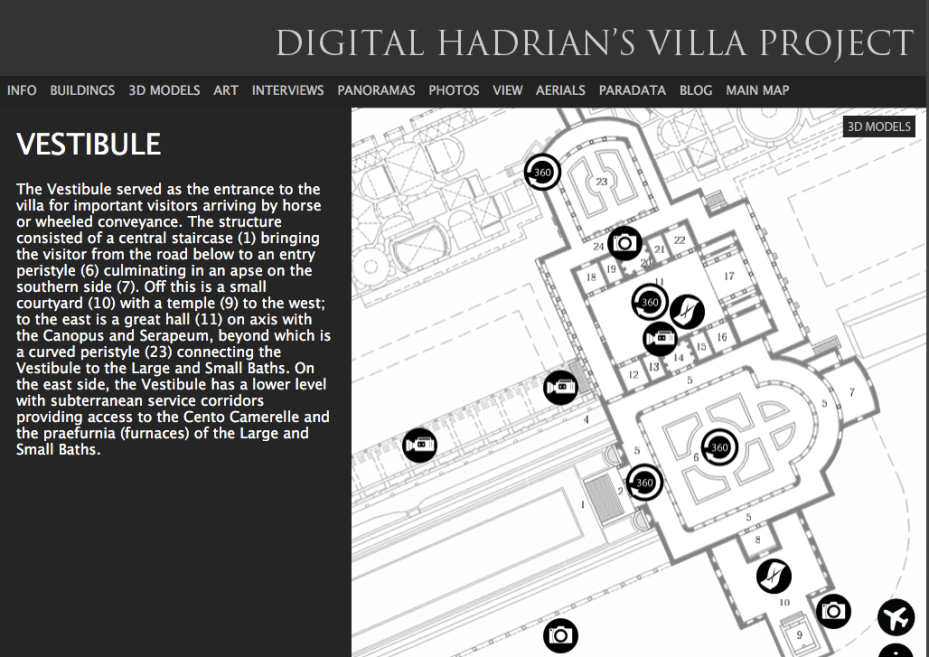

VESTIBULE

My view towards the site of the Vestibule. I’m standing on the Promenade which is to the west of the Small Baths. Below me, an entry driveway once ran along the length of this grassy-trough. That driveway led to the Vestibule’s grand portico.

Aerial View: Vestibule: to the center-left (long grass entry drive is

at the upper-left). Dead-center: The Large Baths.

Top-center: The Small Baths.

Courtesy of DHVP

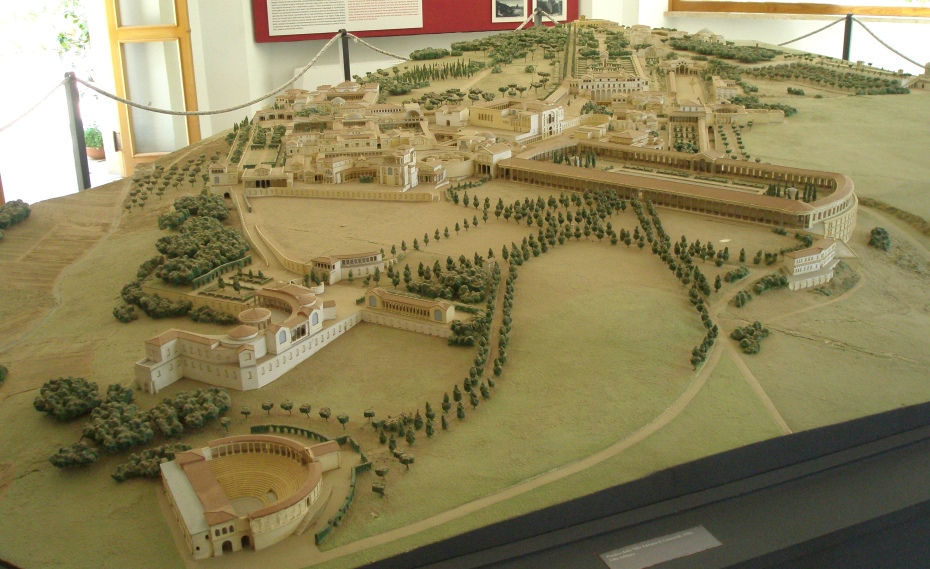

In the Visitors’ Center: The central portion of this model

shows the Vestibule Complex, which juts out from the

West-facing Promenade. The long approach drive is below

the Promenade. Under that Promenade, a portion of the

Hundred Chambers can be seen. Behind the Vestibule,

the Small Baths are to the left, and the Large Baths are to the right.

To the left of the Small Baths are the Three Exedras.

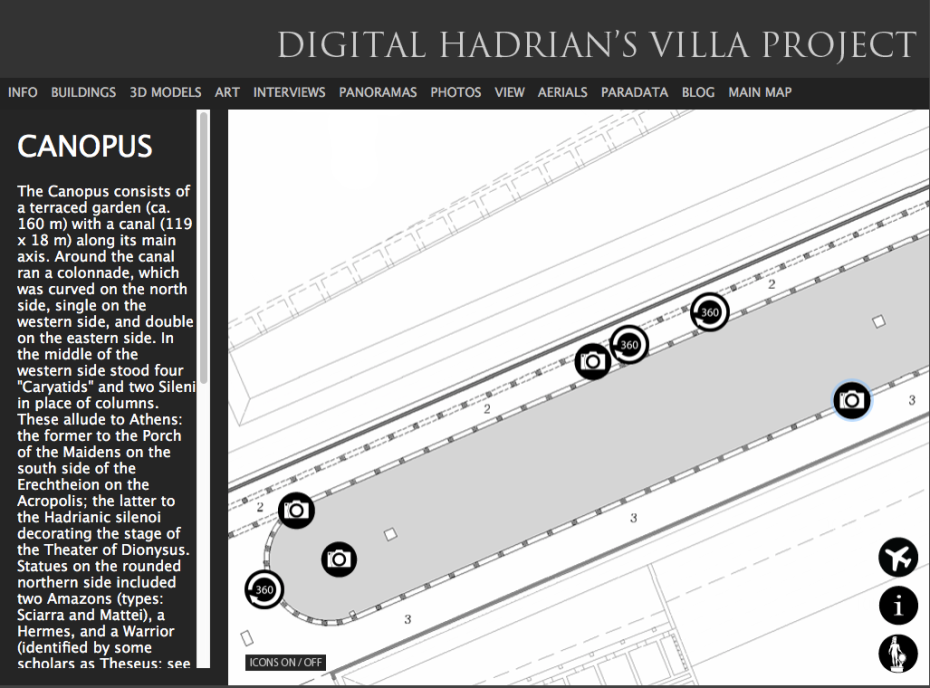

CANOPUS

In her guide to Hadrian’s Villa, the historian Benedetta Adembri introduces the Canopus, which is today the most famous and easily-understood part of the site:

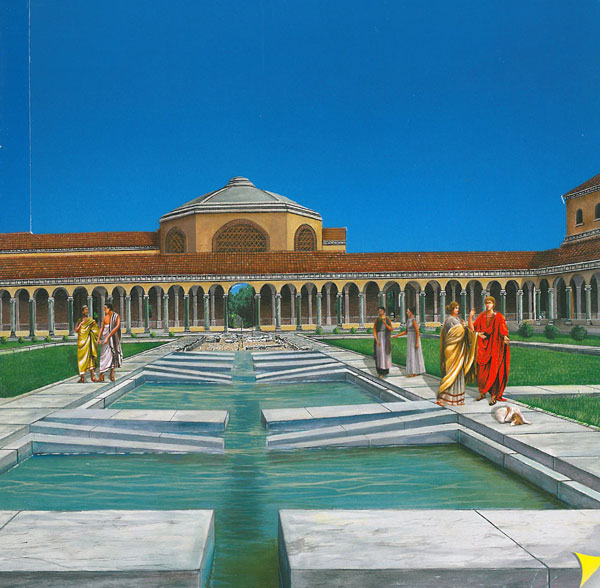

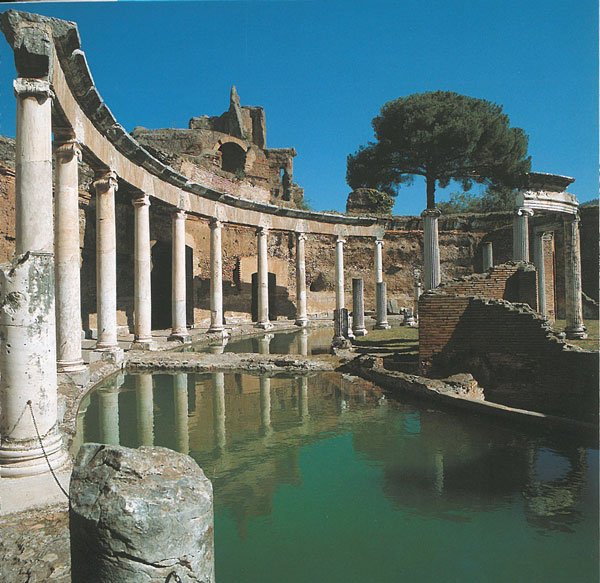

“This complex is one of the only features of the entire villa that can be identified with great confidence as one of the celebrated areas described by Helius Spartianus in the VITA HADRIANA. Constructed in a narrow artificial valley…its principal feature is a large body of water, that terminates with a highly decorated pavilion. This is the Canopus, whose name was borrowed from the canal that linked Alexandria to the city on the Nile delta bearing the same name.” Hadrian’s Canopus “was renowned for the nighttime parties that occurred here. The large pool of water [Note: 390 feet long by 59 feet wide] , situated at the center of the valley, with the short, curved northern end enhanced by a mixed architectural scheme, was bordered to the east by a double colonnade that supported an arbor.

A strip of garden was aligned with the colonnade. To the west, the sequence of columns along the pool was substituted by caryatids.”

Aerial View of the Canopus, with the

Serapeum at the far end of the pool. Image courtesy of Archeolibri.

Rendering of the statue of Scylla (the sea monster of Homer’s ODYSSEY), as she devours mariners. This complex marble assemblage of figures was mounted in the southern end of the Canopus pool. Courtesy of DHVP

Join me as I stroll along the long, western side of the Canopus pool. I’m heading in the direction of the Serapeum, which is the complex of buildings at the southern end of the pool.

All of the statues which are arranged around the perimeter of the Canopus are concrete castings of the original marbles, which are now stored indoors, on the Villa’s grounds.

This reclining statue is the personification of the river Tiber.

Although most of the original statues were, over the centuries, moved to other villas or museums, the number of statues which remained in-situ indicate that, around the Canopus, Hadrian had assembled his largest collection of sculptural pieces.

A closer look at a concrete casting. Most of the site’s original marble statues were in fact copies of earlier, Greek masterpieces, commissioned by Hadrian.

The northern end of the Canopus. To the far-left, the partially-visible statue has usually been called “Ares,” but markings on the statue’s arm indicate him to be Hermes.

The closest statue is called the Canephor Silenus caryatid.

[Note: Canephor figures always carry baskets on their heads. Silenus represents a tutor to the god Dionysus. The concrete cast of this particular statue’s head-basket is missing. ]

Across from the six caryatids, you see a steep, grassy-incline, which runs along the length of the eastern side of the Canopus.

“Recent archaeological campaigns aimed specifically at the organization of the gardens at the Villa have shed considerable light on the location of shrubs and flower beds as well as their relationship with the fountains and pools that complemented the gardens and peristyles. Furthermore, at the foot of the slope along the eastern side….archaeologists have uncovered a long flower bed that ran parallel to the edge of the pool and contained rows of terracotta flower pots; the pots were of various dimensions, but each vessel bore characteristic holes on [their sides and bottoms]. The intentional placing of holes in the pots served to allow the roots to enter the surrounding earth. As the roots of the various species of plants reached their maximum dimensions and there was no need for the arrangement of pots in a decorative manner…the plants were either placed into larger pots or directly into the soil. Archaeologists have been able to date the organization of this garden to the era of Hadrian, on the basis of the types of amphorae [aka “pots”] recovered through the excavations. In addition to the ceramic evidence, maker’s marks [Oh, these Romans! Who were compelled to document Every Little Thing!] preserved on some bricks [in the area] point toward Hadrian’s time.”

SERAPEUM

At the Serapeum there’s abundant evidence of the many and ingenious ways in which Hadrian’s hydraulic engineers used water. As mentioned, the land upon which the Emperor chose to build his enormous Villa complex formed a continuous slope, with the highest elevation being at the southern end (uphill from the Serapeum). The site’s primary water source was tapped into at the top of the slope, and gravity was largely sufficient to direct water down to concrete channels which were built atop the Serapeum’s roof.

Some of those roof-level channels directed water toward the recessed dining area. At this spot, the water then cascaded down into the room; creating a virtual curtain of droplets and mist…all to keep the interior of the banqueting area cool, even during high summer.

A rectangular pool, which is separate from the long expanse of the Canopus pool, is set directly in front of the Serapeum.

That enormous CHUNK of masonry in the foreground is a long-ago collapsed fragment of the front portion of this open-air pavilion. Happily, two people strolled by, just as I took this photo; remembering human-scale is necessary at Hadrian’s Villa, where everything is

Super-Sized.

Behind the front “porch” of the Serapeum, this series of interior rooms, formed in telescope Plan, extends back into the hillside. The niches contained sculptures or fountains.

Fresco decorations from the vaults in the western substructures of the Serapeum. Courtesy of Soprintendenza Archeologica per il Lazio.

Now, climbing the stairs in the southeast corner of the Serapeum, we get some higher views:

From the top of the southeast stairway at the Serapeum, we get a good, central view back down into the domed, open-air pavilion.

The presence of a STIBADIUM, or TRICLINIUM COUCH, inside the Serapeum’s central pavilion confirms that this was a large space for

open-air banqueting. The Stibadium, consisting of a semi-circular brick base with an inclined surface, was during Hadrian’s time, covered with carpets and cushions: guests reclined here during banquets, as they were surrounded by cooling waters, which cascaded in waterfalls, trickled down walls, splashed in fountains, and lapped at the pool’s edge.

The high path which runs along the eastern side of the Canopus will eventually lead us toward the Large Baths, which are located to the north-east of the rounded end of this long pool.

I keep casting longing glances back at the Serapeum, a place which seems far too beautiful to leave ….

On the eastern side of the Canopus: A crocodile. In the original marble croc, the remains of a lead pipe were found in the mouth, indicating that the crocodile had served as a fountainhead.

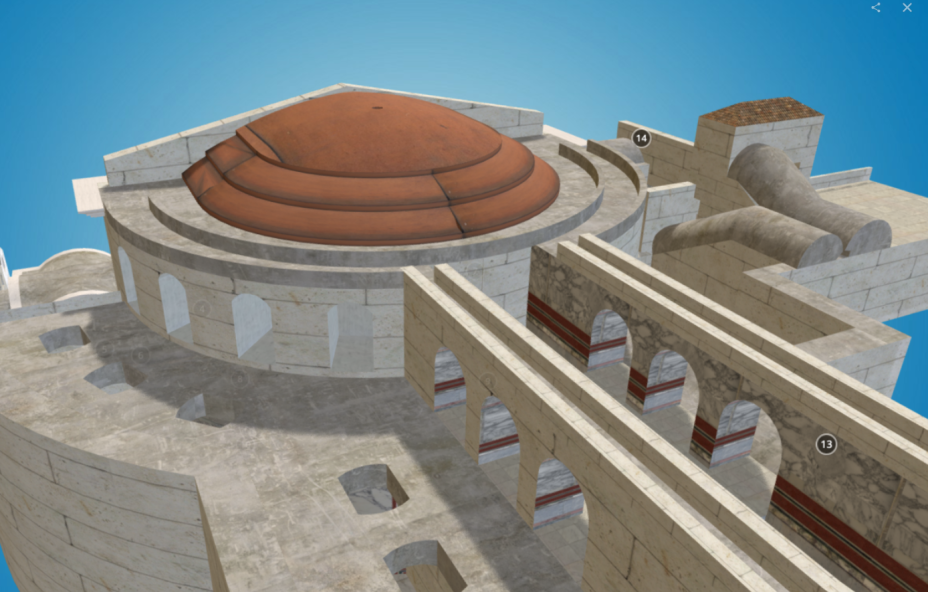

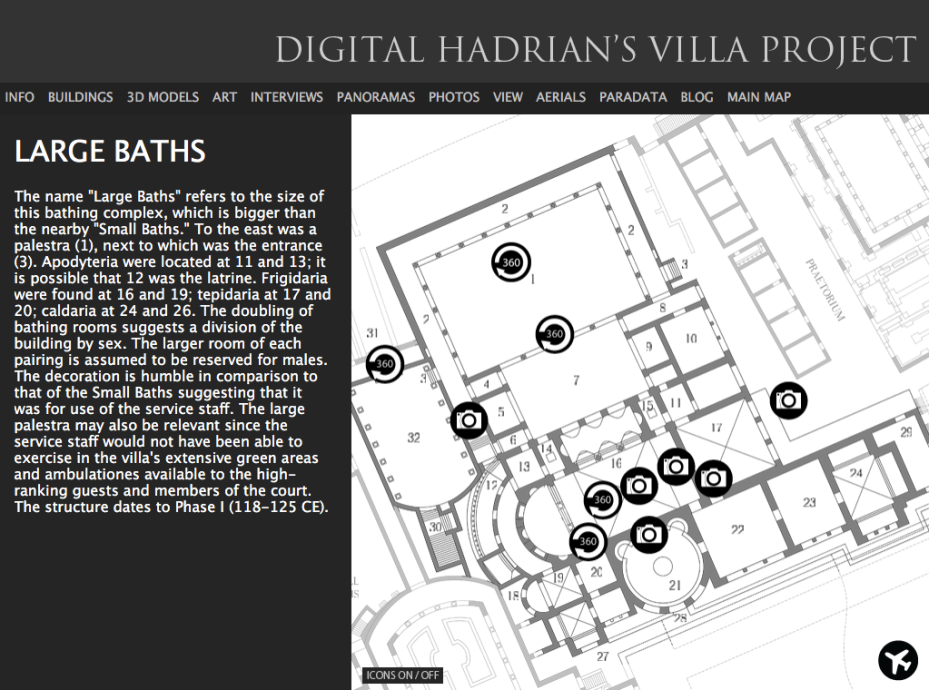

LARGE BATHS

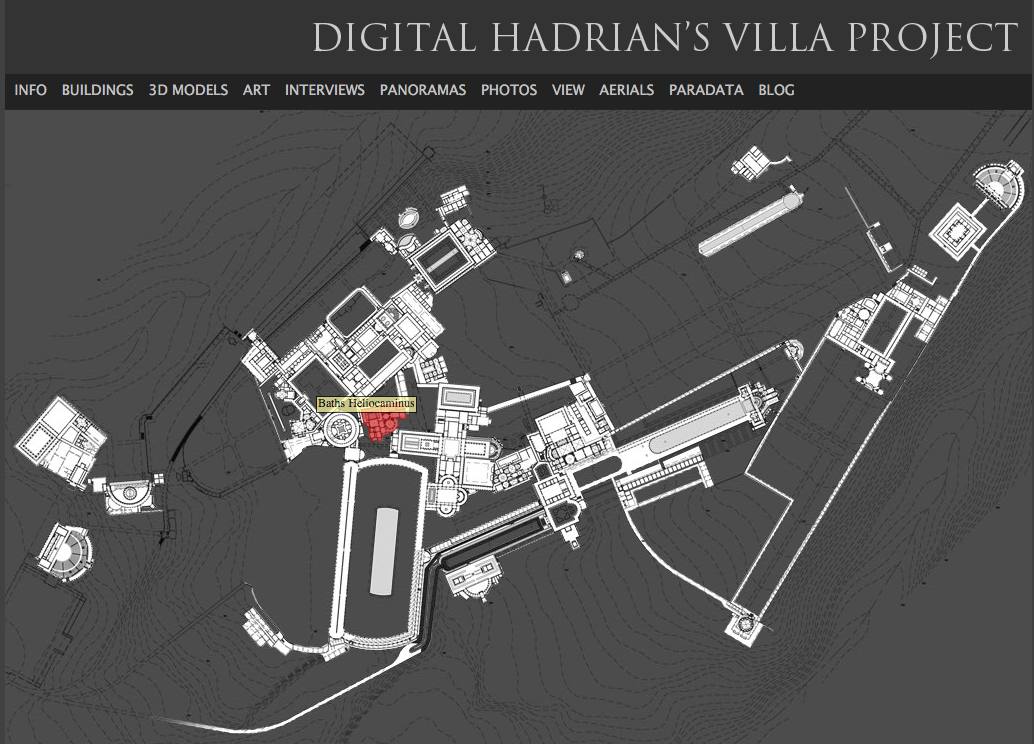

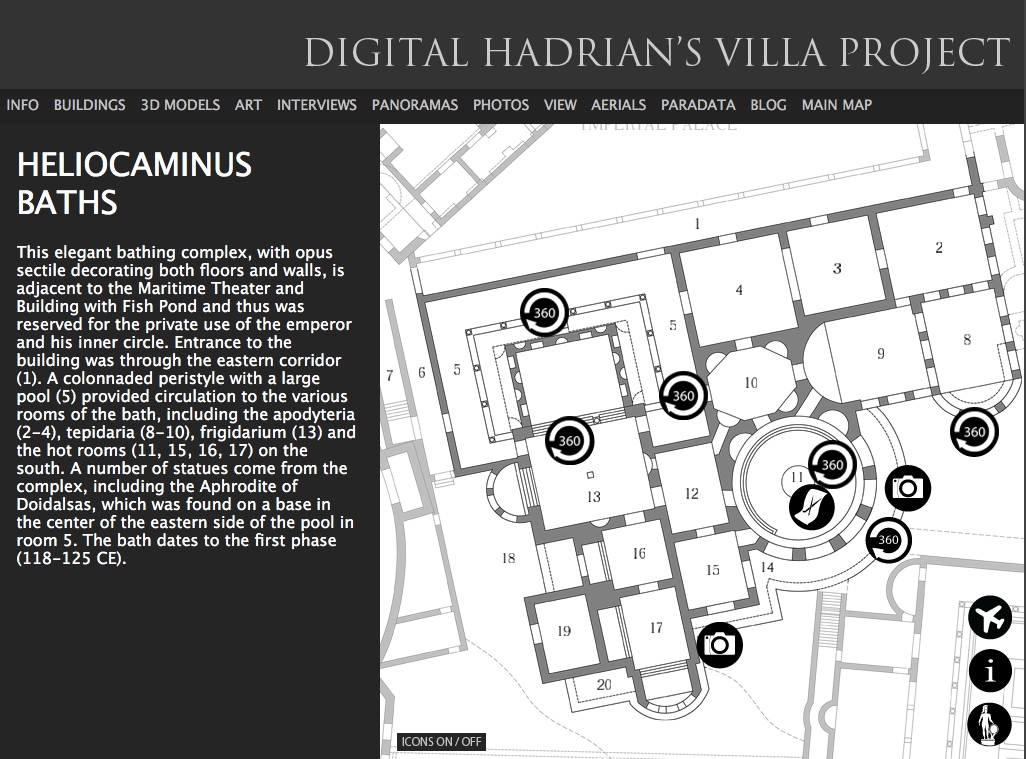

Given the presence of at least three large bath complexes (the Small Baths, the Large Baths, & the Heliocaminus Baths) at

Hadrian’s Villa, a little refresher-course in Roman bathing rituals is called for. We continue now with another excerpt from

Benedetta Adembri’s essential guide to Hadrian’s Villa:

“Most Romans of every social class frequented baths on a more or less daily basis. Since Hadrian’s Villa was the official residence of the emperor, there must have been a great number of courtesans, guests, guards and servants who stayed on the premises of the villa at any given time. This number does not include the craftsmen involved in the ongoing construction of the various buildings and the installation of decorative and sculptural features in interior spaces and in gardens. The use of baths was a response to the norms of hygiene, dictated by medical treatises which prescribed the heating of the body in order to dilate pores through physical exercise and hot water.

This was to be followed by immersions in warm water and, finally, a plunge into a basin of cold water. All bath complexes consisted of

an apodyterium (dressing room), laconicum (sauna), caldarium (hot bath), tepidarium (warm bath) and frigidarium (cold bath), in addition to the gymnasium and other minor spaces.”

“There were also a series of minor spaces for massages, hair removal…and other activities dedicated to the maintenance of the body. The public baths generally contained latrines, as well as shops where a variety of services were offered: barbers, small restaurants, wine dealers and other vendors where goods could be purchased.”

“Within the public baths, there were often separate quarters for men and women, or else the two genders entered the baths at different hours of the day. Hadrian himself passed a law…that men and women must not bathe simultaneously.”

In the large baths, “the embellishments are not as sumptuous as the other baths of the villa…a characteristic that has led researchers to hypothesize that this edifice was frequented by the servants residing in the villa.”

“One needs only consider the costs involved in providing water for all the pools and the supply of wood needed to heat the numerous spaces; there was also the problem of maintenance, that included the frequent changing of water in the pools, which was rigorously controlled.”

And underpinning all of these watery services were what I consider among the most marvelous of all the Villa’s features: the basement heating systems. Steam from enormous boilers—whose waters were kept constantly a-burble over wood-fires—provided in-floor, radiant heat where needed; and dry heat from wood-burning ovens was directed up into the complex through air columns.

First, we’ll take a look at the outside elevations of the Large Baths:

Now we’ll venture inside of the Large Baths:

We enter the Large Baths after having exited from

the Canopus at its northeastern corner. Directly ahead is a cavernous opening into the Large Baths. To our immediate right we see a bit of the corner of the Praetorium.

The Palestra, the large rectangular court to the east of the Large Baths, was an open-air gymnasium, where one’s visit to the

Large Baths would typically begin with a work-out.

We’re back inside of the Large Baths. Consider this: by walking under these nearly-2000-year-old domes, we’re placing ALOT of faith in the structural integrity of the work done by these Roman builders.

And again: back inside the Large Baths. The most thrilling aspects of this place are the infinite ways in which the ruins frame the skies.

Now we’re going to backtrack: around the eastern side of the Large Baths, as we head toward the nearby Praetorium.

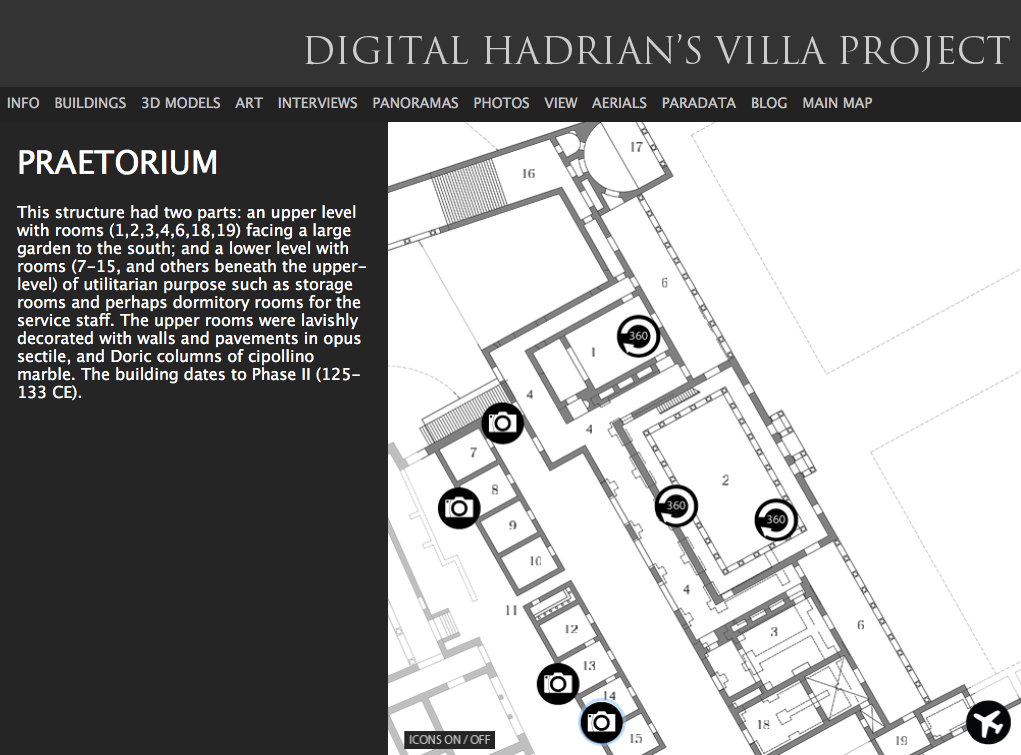

PRAETORIUM

In what is assumed to have been a multi-purpose cluster of buildings, the small, identically-formed chambers which ran the length of the northern boundary are thought to have been dormitories for Hadrian’s praetorian guard. These dormitories were directly across from the Large Baths, where the Villa’s service personnel performed their ablutions. On the southern side of this complex, large, opulently-decorated rooms overlooked an extensive garden.

Aerial View of the Praetorium (on the left) and of the

Large Baths (center of photo). Courtesy of DHVP

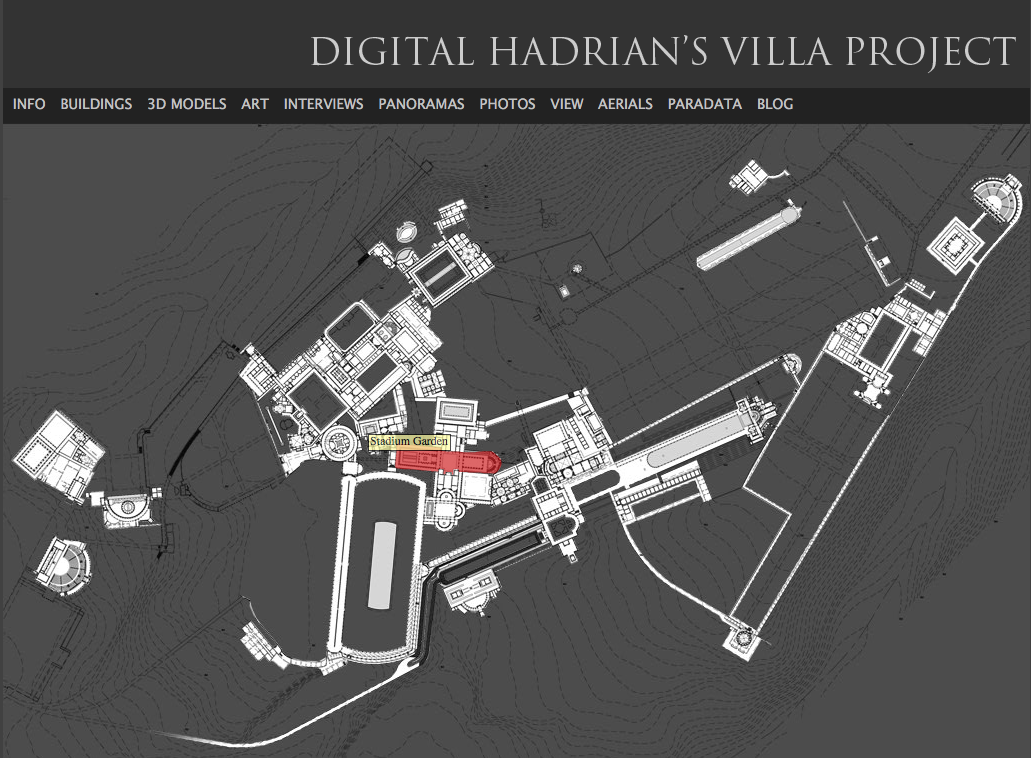

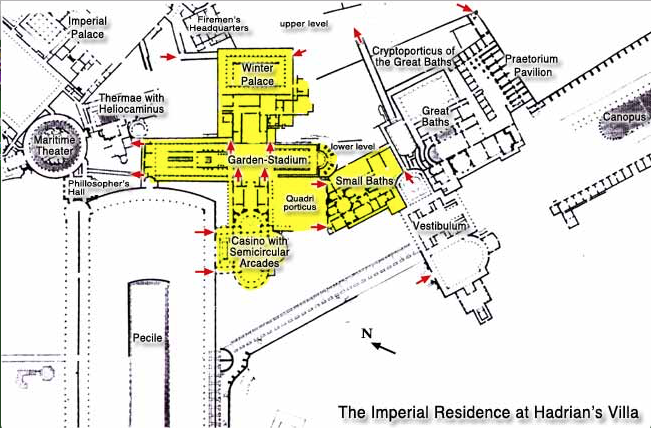

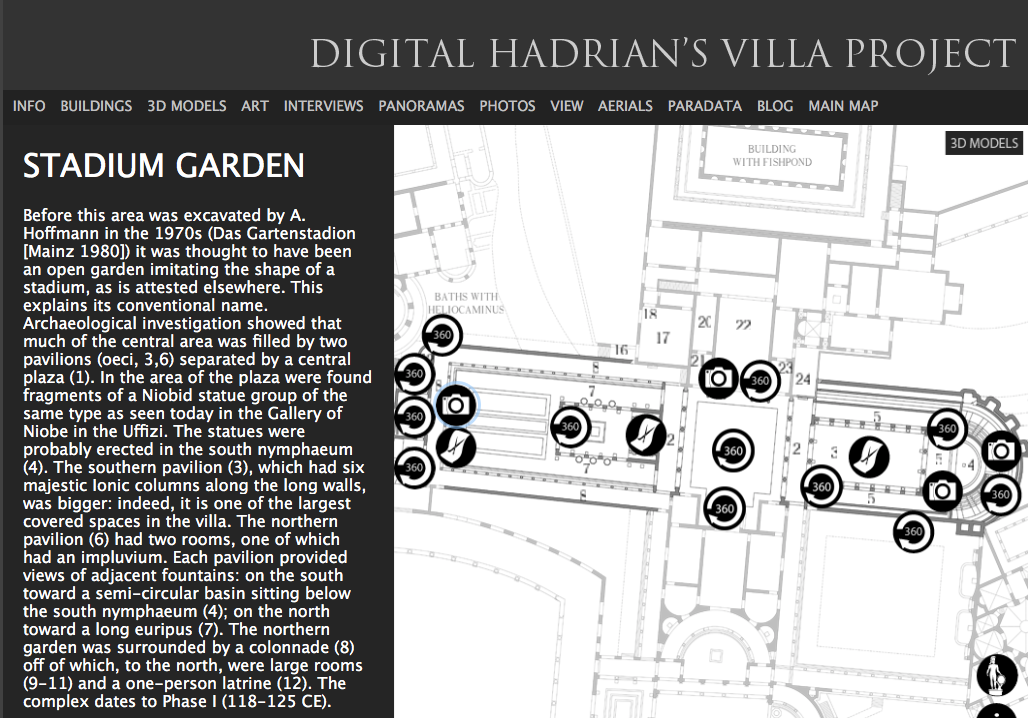

STADIUM GARDEN

If any area within Hadrian’s enormous maze of buildings could be considered the central crossroads for most of the Villa’s above-ground foot-traffic, the Stadium Garden would have to be that place. [Note: I’ll eventually outline the entirely separate Netherworld of servants’ tunnels at the Villa.] The Stadium Garden, aligned on the land almost exactly from north to south, consists of an elongated series of gardens and plazas that are decorated with water features and two large pavilions.

The Small and Large Baths are sited directly to the south of the Stadium Garden, and the Heliocaminus Baths are directly to the north. Due west of the Stadium Gardens is the Triple Exedra complex, which is connected to the Pecile. And due east is the Building With Fish Pond; long assumed to have been Hadrian’s Winter Palace. And in the Stadium Garden archaeologists have found what McDonald & Pinto have called “nearly the full repertory” of ways in which “the splash and sparkle of water” was displayed. “A canal, pools, numerous spouts and jets, channels, cisterns, a grotto, and a theatre of water cascades and planting, thirty-odd features in all,” lay in this long enclosure, which was attached to the Emperor’s own residence.

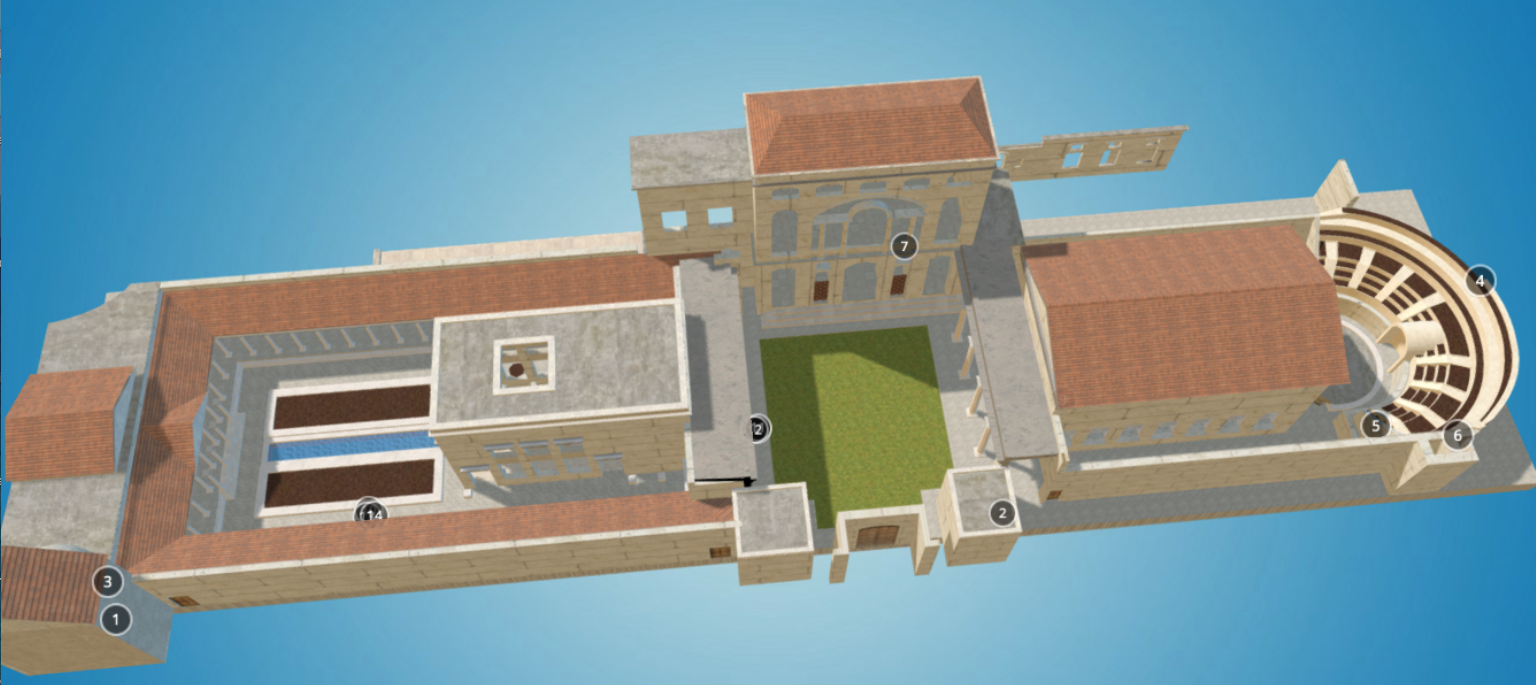

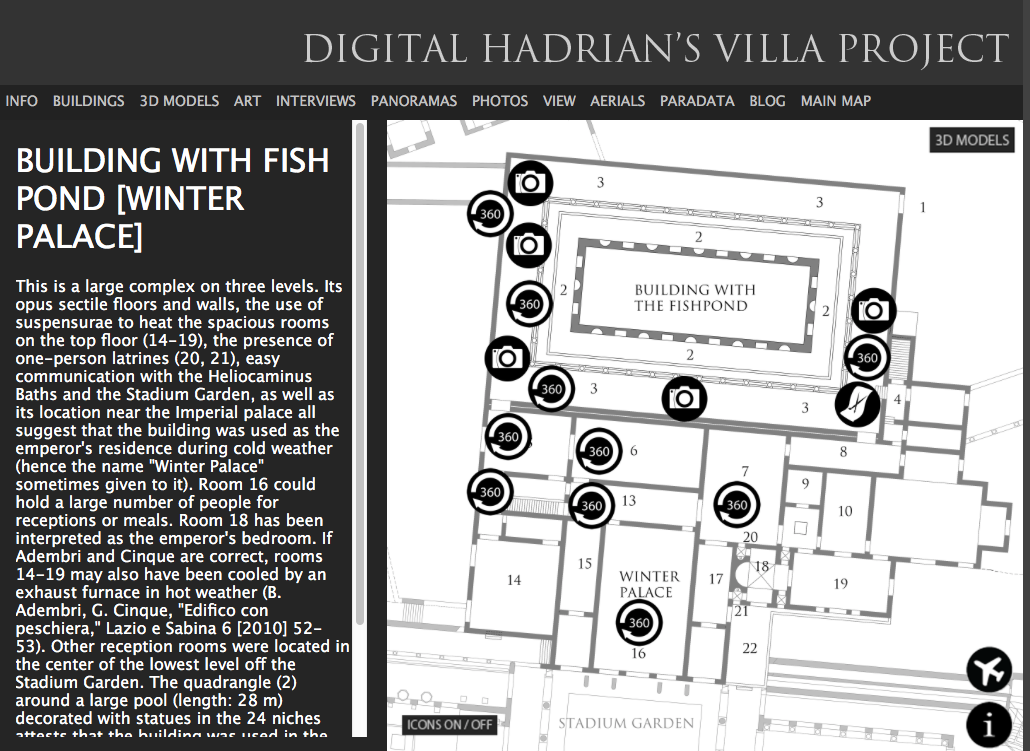

BUILDING WITH FISH POND ( Presumed to be Hadrian’s WINTER PALACE )

The best guess of Villa Scholars is that this 3 storey complex served as Hadrian’s residence during the winter months.

Per Benedetta Adembri:

“Considering the dominant position of the edifice, compared to the surrounding buildings, its centrality within the estate and the rich decoration of the walls and floors which were faced in marble (today only reconstructable based upon the impressions left in the wall plaster and the holes in the wall where pegs were inserted) , it would appear that this truly was the Emperor’s residence, which could be used even during the winter, given the provision of a heating system.

This structure contains all the features required of an Imperial residence: monumental public spaces, a peristyle and covered corridors, and a large garden with dining areas for the summertime, recognized in the adjacent Nympheum-Stadium. “ From the top-most floor of this complex one could gaze westward, over the Pecile, and then further, across the Campagna. To the east of the Palace was a 92 foot long Fish Pond, where waterside seating was provided for those of the Emperor’s guests who enjoyed a bit of angling. The room interpreted as Hadrian’s bedroom faced south west: which provided this most private of spaces with the warmest exposure during Wintertime.

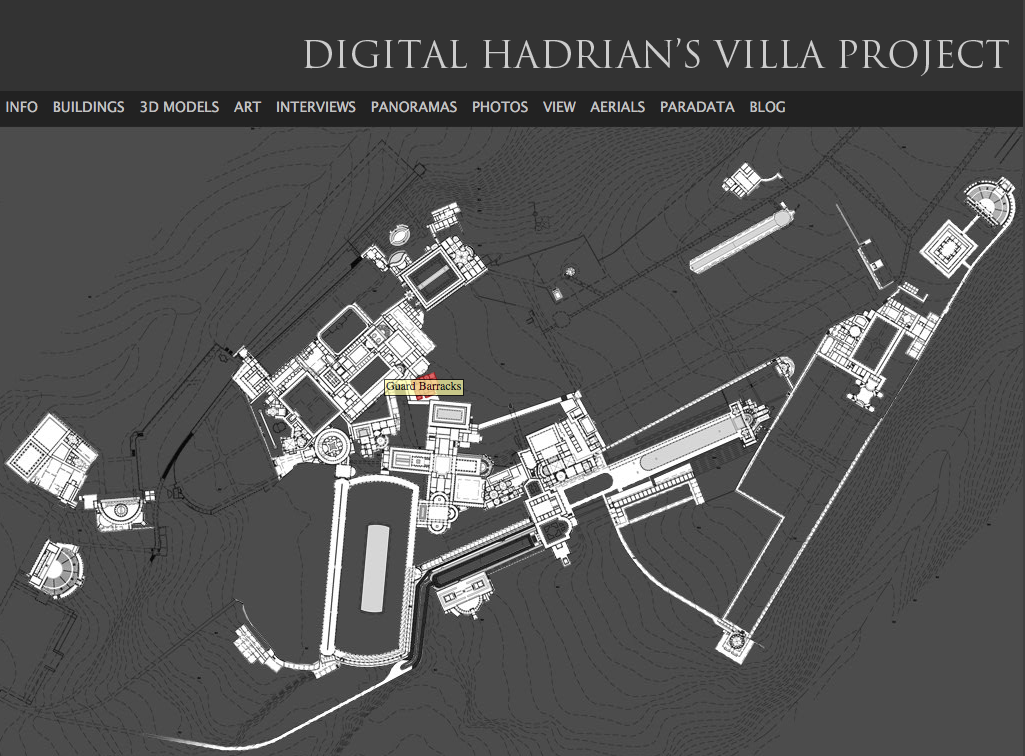

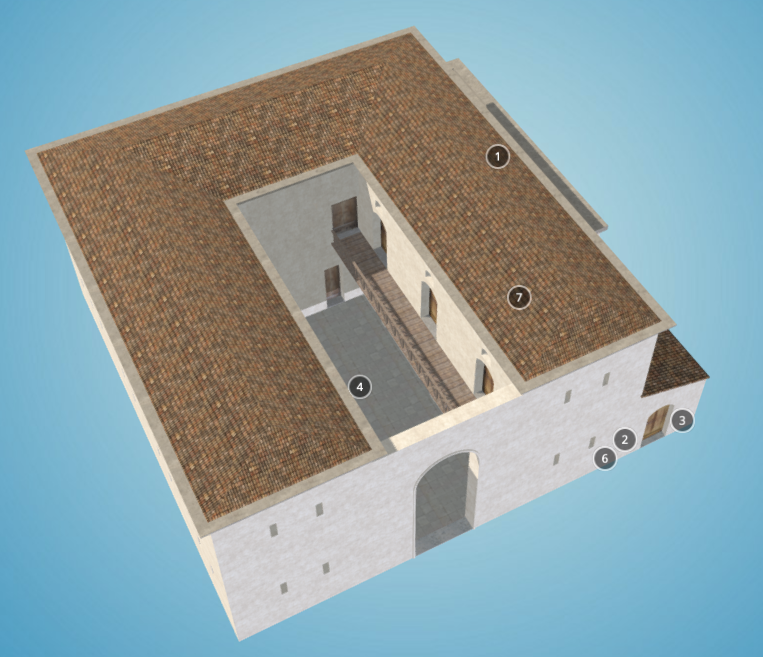

GUARD BARRACKS ( Sometimes called FIREMANS HEADQUARTERS )

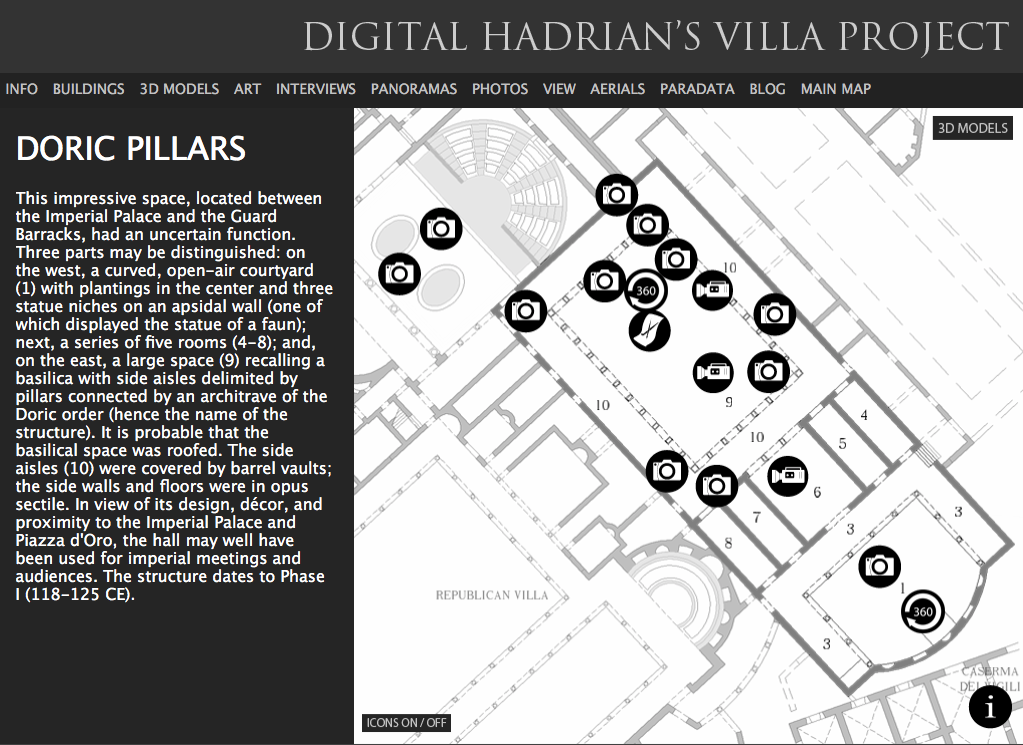

Situated to the northeast of the Guard Barracks, and Hadrian’s winter residence, was a sprawling and interconnected complex of four buildings which are now called:

#1– The Building With Doric Pillars (perhaps the site for tribunals, or for audiences with the Emperor);

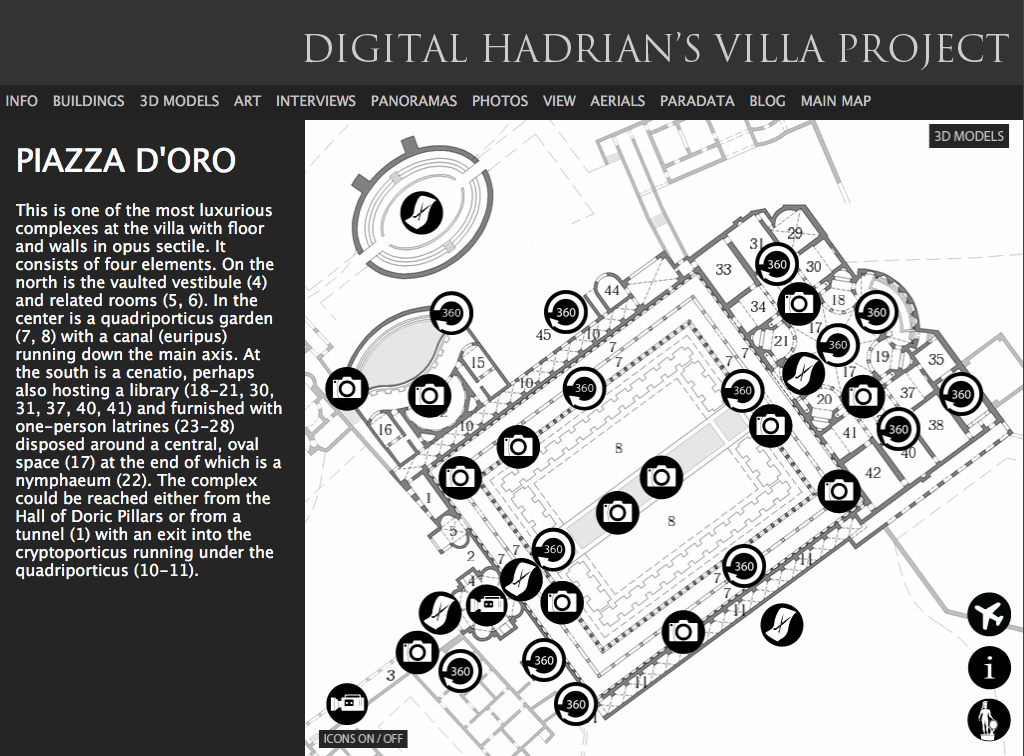

#2– The Piazza O’Oro (lavish structures—and a huge courtyard garden— which were used for God Knows What…but which must certainly have been built to Impress and Generally Knock the Socks Off Of All Those Who Entered);

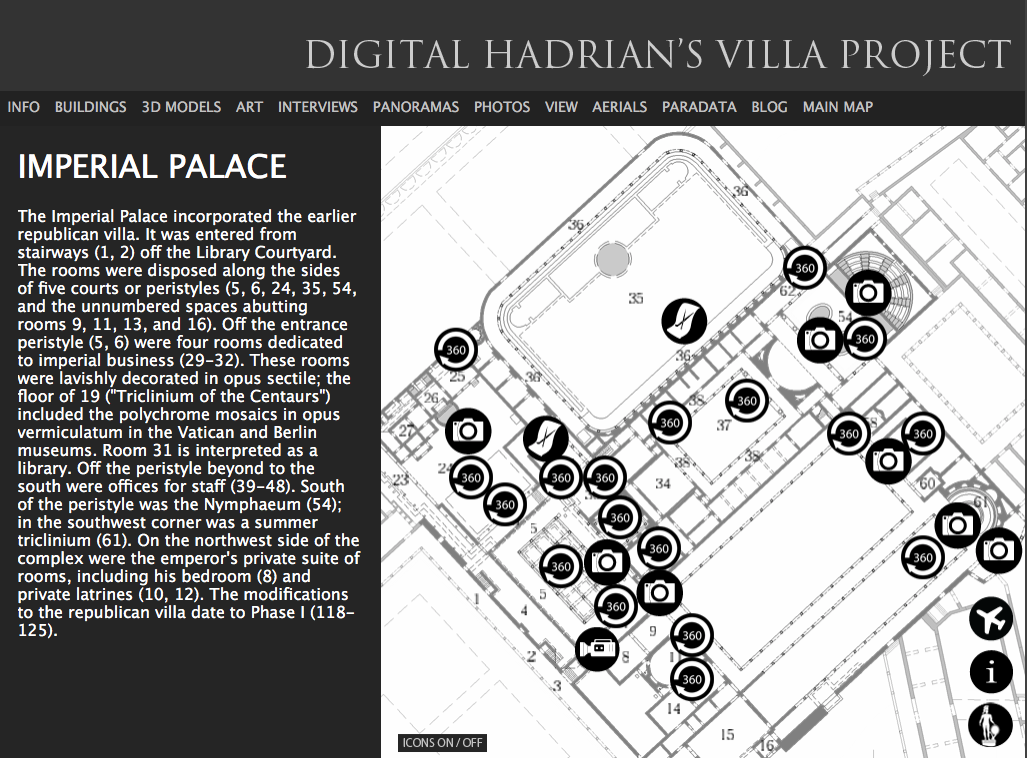

#3– The Imperial Palace (a large, highly-utilitarian, Republican-era villa, which was absorbed into Hadrian’s building programme, and where Hadrian is thought to have slept, during the summer months);

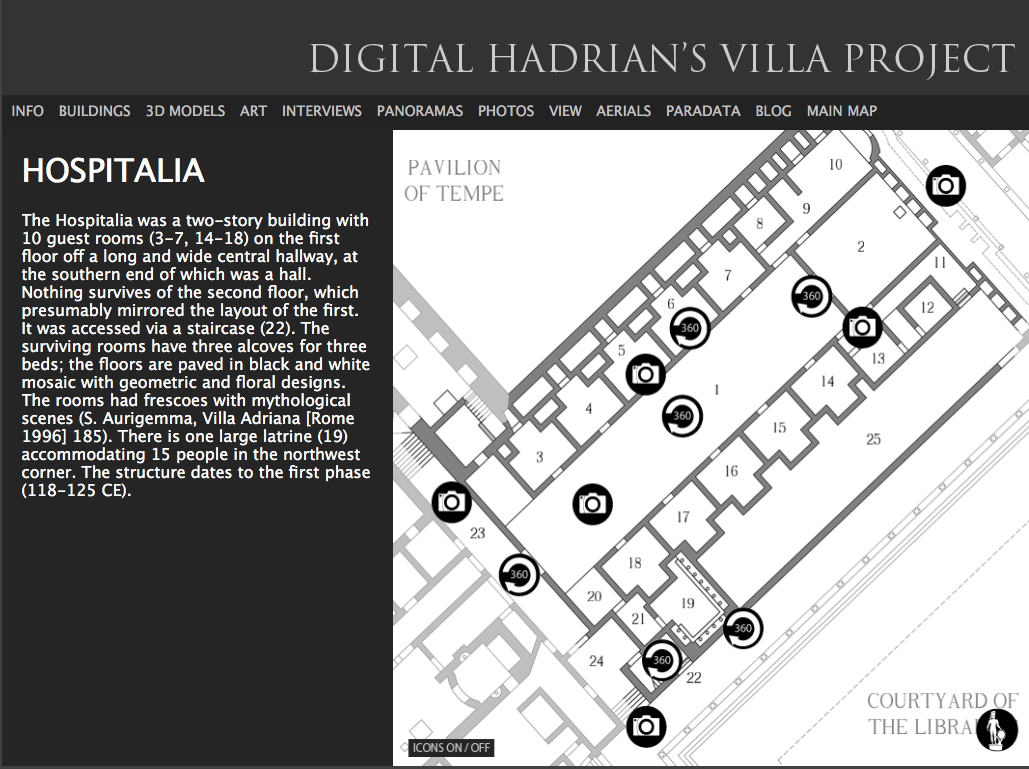

#4–The Hospitalia (where lodging was most likely provided for visiting officials, in small, dormitory-like rooms).

It is assumed that, within this compound of magnificently decorated structures, Hadrian went about the daily business of meeting with his minions and subjects, as he managed his Empire.

Map of the Structures which were on this site, before Hadrian began building his Villa. Some of these buildings were incorporated into the new construction.

Courtesy of Marina De Franceschini

BUILDING WITH DORIC PILLARS

PIAZZA D’ORO ( THE GOLDEN SQUARE )

IMPERIAL PALACE ( Presumed to be Hadrian’s SUMMER RESIDENCE )

HOSPITALIA

Exquisite black and white floor mosaics are still intact in the Hospitalia area.

This style of tiling was “modern,” and appeared in the Hadrianic Age. Image courtesy of Soprintendenza Archeologica per il Lazio.

HELIOCAMINUS BATHS

The great Roman architect Vitruvius ( born c. 80—70 BC; died after c. 15 BC ) devised explicit specifications for constructing,

and then heating, buildings. Hadrian, who was smart enough to follow Vitruvius’ good examples, thus built all of the Bathing Complexes at his Villa so that the heated rooms of those Baths faced south-west, as Vitruvius prescribed. Benedetta Adembri reports, “the south-west exposition exploited the hottest rays of the afternoon sun, when the Romans generally bathed.”

The Aphrodite of Doidalsas: formerly mounted in the Heliocaminus Baths. Now on display at the Museo Nazionale Romano–Palazzo Massimo alle Terme, in Rome.

The Heliocaminus Baths are directly to right, in this photo.

In center: Donn Brous walks toward the dome of the Philosophers Hall. Behind the grove of trees to the right of the Philosphers Hall is

the site of the Maritime Theater (which, sadly, wasn’t open to visitors).

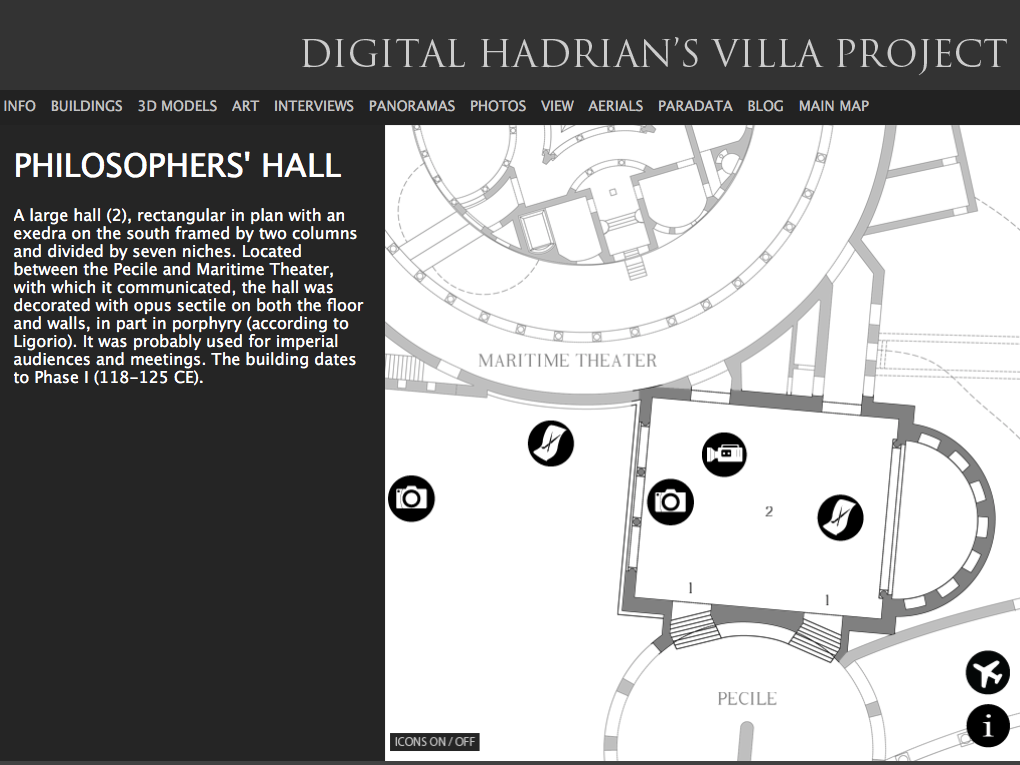

PHILOSOPHERS HALL

The confusingly-named Philosophers Hall has seven large niches in its north wall. These long-empty spaces most likely

held a cycle of statuary (probably representing the Imperial family), but clearly, once the Villa’s ruins had been rediscovered, some Head-in-the-Classics-Visitor gazed at those empty niches and had the dreamy thought that — of course! — Hadrian must have displayed likenesses of the most famous philosophers of his time. It’s best to accept that this room with its great apse and marble walls was simply a grand setting for the Emperor’s nuts-and-bolts business of giving audiences and holding councils.

3D Recreation of the Philosophers Hall. [NQ’s Note: The extraordinary, concave portico with double stairways transforms what could have been a forgettable pile of masonry into a sophisticated and surprising building.] Courtesy of DHVP

Aerial view of (to the left) of the half-dome and two side walls of the Philosophers Hall, and (in the center) of the circle of the completely-enclosed Maritime Theater.

Courtesy of DHVP

MARITIME THEATER ( Also called the ISLAND ENCLOSURE, or the NATATORIUM )

These days, only birds and archaeologists are permitted to occupy the interior of the Maritime Theater. Perhaps on my next visit to the Villa, the Powers That Be will allow me to explore this self-contained island, which is the Most-Peculiar, as well as the Most-Glamorous, of all of Hadrian’s creations.

But, before I illustrate the Maritime Theater, which will be our final extended stop on this tour of the Villa’s central area, a digression:

As mentioned, the outer reaches of the Villa complex are largely closed to Visitors. And many of the inner areas can also become inaccessible, due to ongoing excavations, or structural hazards.

Following, however, are notes about some critically-important parts of the Villa (places which I hope will eventually be opened to Visitors, at least on a limited basis ).

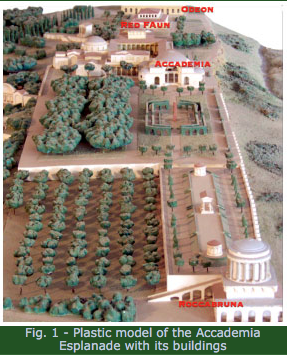

ACCADEMIA ( The ACADEMY )

At the highest, southern end of Hadrian’s estate, the land upon which the compound known as the Accademia stands is privately owned, by the Bulgarini family. Since 2005, Marina De Franceschini has been allowed by the Bulgarini to study the site, which is one of the largest, and least-understood areas of Hadrian’s Villa. Her project, which she calls “Accademia: Hadrian’s Secret Garden,” is ongoing.

One of the most famous art treasures ever found on any ancient Roman site came from the floor of a room adjacent to the Accademia’s Rotunda. In 1737, the mosaic, now called the “Dove Basin” was discovered.

The Dove Basin is attributed to Sosos of Pergamon, a Greek mosaic artist who lived in the second century BC. Sosos worked exclusively with cubes of colored marble. We don’t know if the mosaic unearthed at the Accademia is an original, or if Hadrian had an exact copy of the Dove Basin made for himself (as was his wont). Whichever the case, this exquisite mosaic is now displayed at the Capitoline Museum, in Rome.

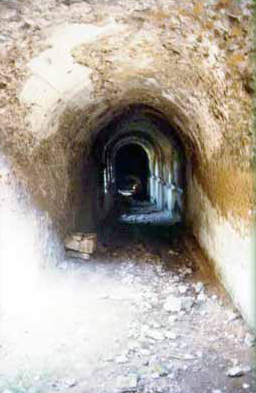

UNDERGROUND FEATURES OF THE SITE

Not only did Hadrian build far and wide across his land; he constructed networks of corridors, as well as tunnels, below ground. Identifying those underground circulation paths and roadways, without which the Villa could not have functioned, is essential to understanding the true scale of the small city that Hadrian created.

Although regular Visitors aren’t allowed to peer into Hadrian’s Underworld, it’s important in this Diary to mention what’s out of sight at the Villa.

Two types of below-grade structures were built:

#1 — The Cryptoportico: a normal feature in large Roman buildings.

Covered, semi-subterranean corridors whose vaulting supported above-ground structures, Cryptoporticos had natural lighting, which filtered in through openings at the top of the arches. Archaeologists at the Villa have long known of these sunken corridors, but the full extent of the Villa’s web of sub terrestrial hallways will probably never be known.

This network of long, hidden galleries ( which connected the basement of one building to the next, and to the next… ) at Hadrian’s Villa served many purposes. Some passages were secret, and allowed the Emperor privacy of movement. Other passages were lavishly decorated: reserved for the pleasure-walks of nobles who wanted exercise, during foul weather. Many more cryptoporticos were used for access to buildings, by the hundreds of servants who staffed the Villa (as well as could be arranged, Hadrian’s Help was Out-of-Sight-Out-of-Mind). Supplies of firewood to the various Bath Houses could be delivered invisibly, via oxcart, through the largest of these hidden corridors. Wherever above-ground serenity and efficiency were desired at Hadrian’s Villa, cryptoporticos were sure to be built.

Cryptoporticus Under the Piazza D’Oro.

This connected the Piazza D’Oro with the Great Trapezium underground road system.

Courtesy of Marina De Franceschini

The Cryptoporticus With Mosaic Vault was inherited from the ancient Republican villa, and preserved and incorporated into Hadrian’s design-scheme for his Winter Palace.

XIX Century engraving, by Penna.

Courtesy of Marina De Franceschini

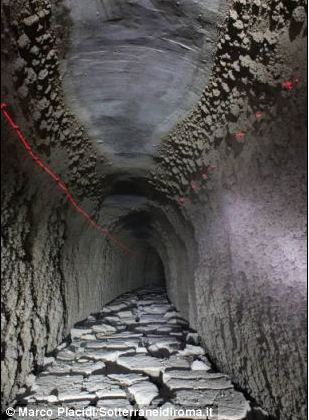

#2 – Underground Roadways and Tunnels: Hadrian’s Villa has an enormous subterranean road system, which is unlike anything else

(that we know of) from his time.

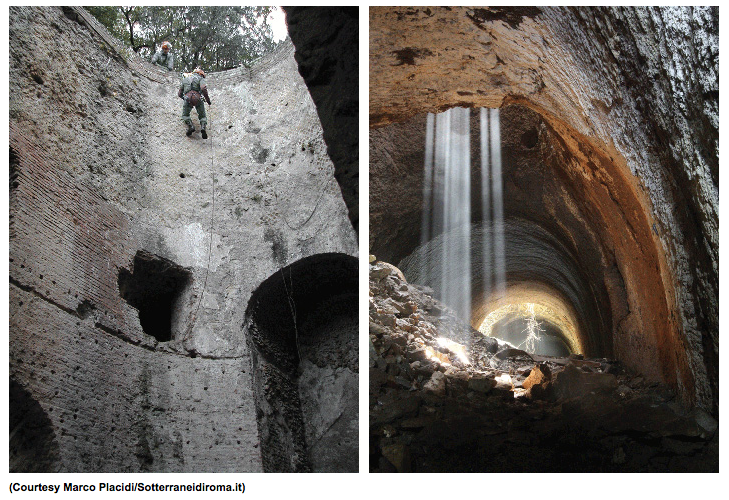

Investigation of the far-reaching system of large, and deeply-dug tunnels that honeycomb the ground below Hadrian’s Villa has only recently begun, but the scope of that which has been discovered since 2001 is already mind-boggling.

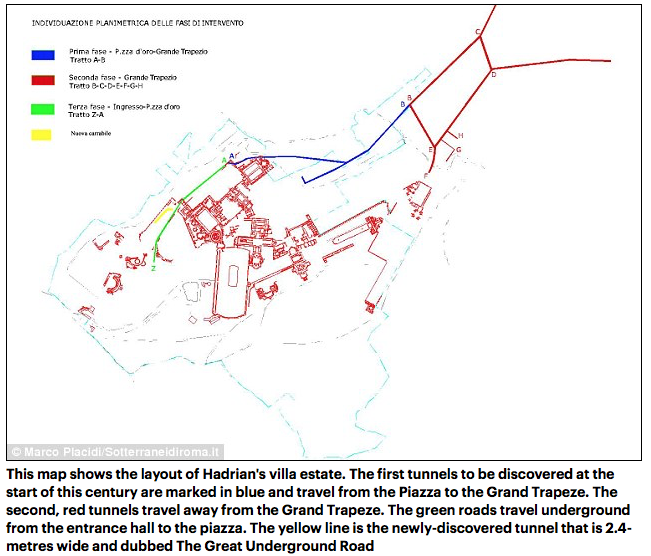

In 2001, a group of amateur Italian cavers began to look for the networks of roads that had been long-suspected to lie beneath 296 acres of fields of Hadrian’s estate (all told, Hadrian’s entire estate might once have covered 600 acres). The members of Underground Rome, led by Marco Placidi, are all experienced cavers; their explorations are directed by archaeologists, who have schooled the cavers in all necessary scientific protocols.

Underground Rome’s cavers have explored nine miles of the Villa’s water pipes and sewers. They’ve charted many small, dirt-filled tunnels in the vicinity of the Accademia and the Canopus. They’ve burrowed into cavernous passageways which lead from the Villa’s most densely-built sections out to the countryside. They’ve mapped the huge trapezoidal circuit that’s called the Great Trapezium (where donkey carts making deliveries of supplies for the Villa would enter, pause to dump their cargo at a connector tunnel which led to the Villa Proper, and then proceed back toward the exit to the Above-World).

Another breakthrough came in 2013, when—as cavers do—Placidi and his crew dropped into a yet another small hole in the ground. They discovered a light shaft leading to a previously-unknown tunnel. Although filled nearly to its ceiling with soil, at 17 feet wide, they’d found a roadway which could accommodate two-way cart-traffic. Underground Rome’s adventures are continuing: by digging, wriggling, and—where spaces are too tight for even a wriggle—by mounting cameras on remote-controlled vehicles, they’re methodically redefining the dimensions of Hadrian’s Villa.

Locations of the Tunnels which have been discovered, since 2001, at Hadrian’s Villa.

Image courtesy of Marco Placidi/

Sotterraneidiroma.it

This newly-discovered tunnel begins at the center of the complex and runs for half a mile to the 700 meter circular spur, which is called the Great Trapezium, or Grande Trapezio. [Note: 700 meters equals 2300 feet, equals .44 miles]

Image courtesy of Marco Placidi/

Sotterraneidiroma.it

A double-wide tunnel in the Great Trapezium. Photo courtesy of Francesco Lerteri and

Marina De Franceschini.

Photos taken in August of 2013 of the ongoing explorations of the Underground World of Hadrian’s Villa

Image courtesy of Marco Placidi/

Sotterraneidiroma.it

We Return to THE MARITIME THEATER (or ISLAND ENCLOSURE, or NATATORIUM )

Maddeningly, this structure — which Benedetta Adembri calls “the symbol of the singularity and the innovation in the architectural design of the entire Villa complex” – isn’t open to normal Visitors.We can probably blame Pirro Ligorio for assigning the overwrought “Maritime Theater” label. I prefer “Island Enclosure:” it better describes this place … which is effectively an isolation chamber.

With a diameter of 150 feet, the Island Enclosure’s outer footprint nearly matches that of the Pantheon. A tall ring wall encircled the Enclosure and provided perfect privacy for the occupants of this jewel-box hideaway. Running inside the entirety of the perimeter wall was a colonnade, with forty evenly-spaced Ionic columns mounted along the outer edge of a doughnut-shaped moat. The moat, completely lined in white marble, had crossings at two points, via wooden bridges which could be raised, so as to block access to the inner Island. On the circular, artificial Island Hadrian used dizzying combinations of interlocking, geometrical shapes to cram together many small, interconnected rooms: which included various lounges, a library, a dining area, two little bedrooms, a full complement of bathing spaces (hot, warm, and cold), and a private latrine. Dead-center on the Island, a garden atrium was defined by four inner walls, which were arranged in an eccentric, convex configuration. In this inward-looking, Play-House-Fit-For-An-Emperor, all of the creature comforts were provided…but in miniature.

During 18th century excavations of the Island Enclosure, this red marble fawn was discovered. It is now displayed at the Capitoline Museums, in Rome. Image courtesy of the Capitoline Museums, Rome

Hadrian, who built so compulsively in the 2nd century, was, in many instances, expressing himself in an architectural style which wasn’t given a name until the 17th century. Consider the great variety of spaces on the following, un-annotated floor plan of the Island Enclosure…and then imagine the ways in which the Emperor could have decorated his walls, and modeled his vaulted ceilings. The Merriam Webster Dictionary defines “Baroque” as:

“Marked generally by use of complex forms, bold ornamentation, and the juxtaposition of contrasting elements often conveying a sense of drama, movement, and tension.” “Baroque” is as good a description as any, for Hadrian’s design-work, here on his Island Enclosure.

This un-annotated Plan of the Island Enclosure reveals the intricacy of Hadrian’s geometry. But remember: above the marks of foundation walls and footings that you see here, Hadrian built many different kinds of vaults and ceilings. We can only guess about the profiles of those rooflines.

Recreation of the Maritime Theater, AFTER Hadrian’s time. (you’ll note that the artist hasn’t drawn the central structures). Image courtesy of Archeolibri.

Aerial View of the Maritime Theater.

Directly below the Theater are the remains of the Greek Library.

To the right of the Theater is the Philosphers Hall.

Above the Theater are the Heliocaminus Baths.

The grass covered area at the upper right hand corner of this photo is just a small bit of the Pecile’s garden court.

Image courtesy of Soprintendenza Archeologica per il Lazio.

As weary and overheated as we become, during our hours of wandering there, it’s always difficult to tear ourselves away from Hadrian’s magnificent and dilapidated estate. Even if we’re not sure about exactly WHAT we’ve been seeing there in the ruins, a combination of elation and melancholy will overtake any alert and sensitive souls who enter the archaeological site. Elation comes as we’re embraced by the remnants of the Emperor’s extraordinary buildings and courtyards. It comes when we brush our fingers across the Romans’ ancient stonework. It comes while we’re gazing across the vast stretches of the Villa’s water gardens. But then melancholy edges in, as we remind ourselves that, in the moment he died, Hadrian’s estate at Tivoli — this singular creation, the likes of which the Roman Empire had never before built — would became irrelevant and burdensome to his successor.

The Villa was itself a personification of its Emperor, and, as things turned out, the estate was to be the final, magnificent display of the Roman Empire’s wealth and reach. “Sic Transit Gloria Mundi.”

Glories of the World Pass.

Visits End. We prepare to exit the Site:

We’ve returned to the Portal in the Great North Wall of the Pecile, and are looking toward the long cypress-lined avenue, which will lead us downhill, past the Visitors’ Center, and finally to the Parking Lot, where we’ll have to deal with the Realities of Tour Bus Mobs, Ice Cream Vendors (those…. I like), and Traffic.

This grand allee of cypress trees was planted in the mid-1700s by Count Giuseppe Fede, an amateur archaeologist who in 1724

began to buy up as many parcels of land at the site of Hadrian’s Villa as he could. Were it not for Count Fede’s efforts to secure the ruins of the Villa, the site would very likely be in much worse shape than it is. At the end of the 19th century, most of the remains of the Villa then became the property of the Italian kingdom.

Excavations at Hadrian’s Villa have been proceeding, in fits and starts, since the mid-1500s … and time is not on the side of those who seek to completely unravel the mysteries of Hadrian’s grand and continually-crumbling creation. Since Pirro Ligorio began to look seriously at the ruins, opinions about the Villa’s original forms and functions have constantly changed.

A rigorous archaeological approach to excavating and interpreting the ruins must form the bedrock for our quest to better understand what Hadrian built in Tivoli. The research and explorations that are being done by scholars such as Marina De Franceschini, and Bernard Frischer, and by the intrepid cavers of Underground Rome, are of critical importance.

But beyond these scientific and historical approaches, speculations about the psychology of Hadrian (aka: The Man Who Caused It All To Be Built ) are also necessary, and inevitable.

American architect Charles Moore, in his 1960 essay for PERSPECTA, presented this entertaining and always spot-on commentary about Villa Adriana, just a smidgen of which I’ll include here (with permission granted by the MIT Press).

“Hadrian’s entry in the megalomania division, though, since it bears so heavily the stamp of one man, seems to come much closer to the edge of madness. It is the product, as Eleanor Clark pointed out, of a craze to build, very like those nineteenth-century follies in the United States whose owners, obeying only the dictates of some irresistible inner urge, added crazily, continually to them, and were generally only stopped by death. But this is not crazy in quite the same way, because this is often beautiful. It is perhaps much more parallel with Thomas Jefferson’s efforts at Monticello, the work of a man moved to establish himself firmly on a piece of land, and to reaffirm the establishment constantly by building there, while his duties and his interests kept him far abroad. “

“For Hadrian’s conduct of his office…was based on travel. He strengthened the Roman Empire by traveling through it, and formed his own character along the way. He had been born in Spain, but Athens was said to be his favorite place, and the art of Greece, some of it already over five centuries old, his ideal, though he collected art from Egypt and the east, and many other places too, and seems to have found the vaguely oriental charms of a Bithynian more to his taste than whatever Greek talent was available. Indeed, the most striking point of rapport between Hadrian and ourselves is this eclecticism.”

[NQ’s Note: Eleanor Clark’s 1950 essay HADRIAN’S VILLA, which is included in her book ROME AND A VILLA, is a highly impressionistic…and refreshing…riff on Hadrian.]

It is this very eclecticism which has gripped the imaginations of all those who, across the centuries, have clambered over what’s left of Hadrian’s Villa. Even if we’re not consciously analyzing the ruins as we follow circuitous routes around crumbled walls and under fragmentary arches, we’re sensing that, in this place, Hadrian’s ever-changing styles and manipulations of geometric volume seem almost to be experimental.

Hadrian’s Villa, unlike most small cities, was not a place that evolved over time. Its labyrinth of spaces did not grow with sequential generations; its layers of form and richness of meaning were not added onto by consecutive occupants. Instead, Hadrian’s massive estate appeared over the course of two decades…which is nearly in the blink of an eye, at least in the terms of the Ancient World, when buildings were hand-made.

Somehow, with brick and stone, Hadrian has left us a veritable mind map: a physical record of the restless progressions of his artistic tastes and architectural philosophies. Such restlessness resonates powerfully, with our Modern minds.

Copyright 2018. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

5 Responses to The Treasures of Tivoli, Italy. Part One: Explorations of the Archaeological Complex at Villa Adriana