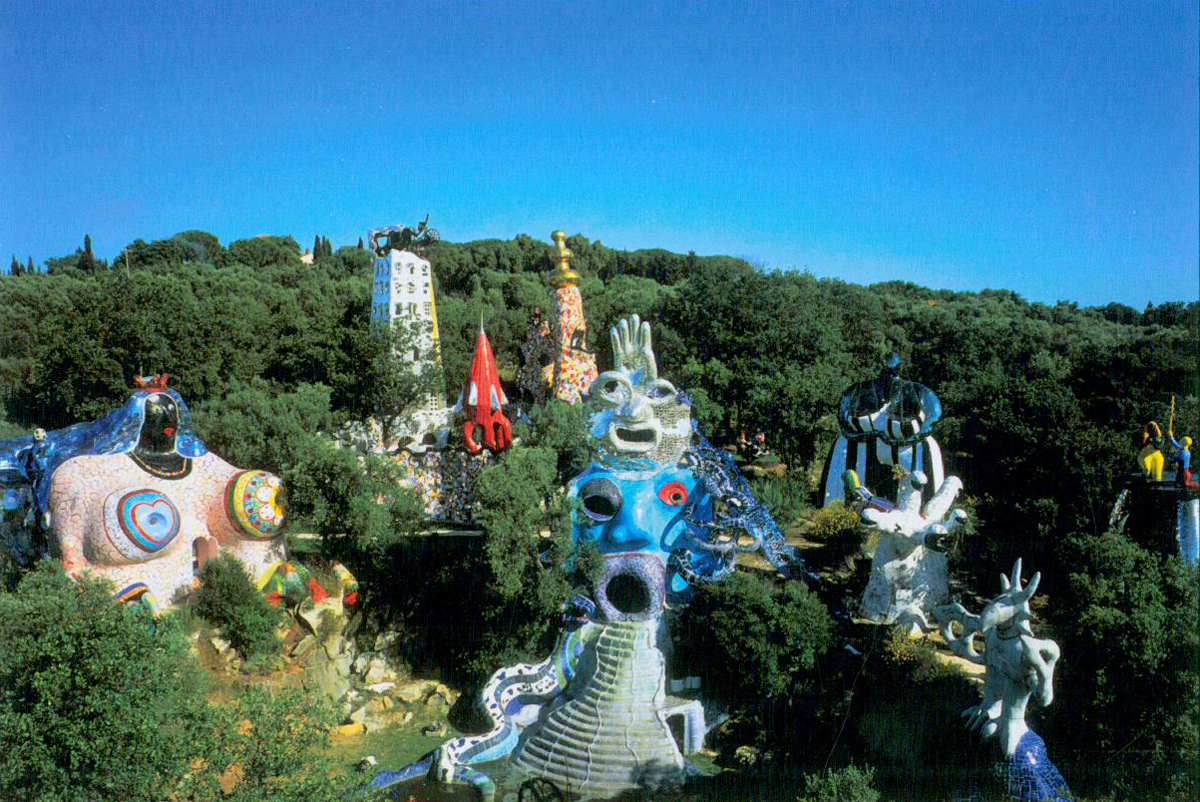

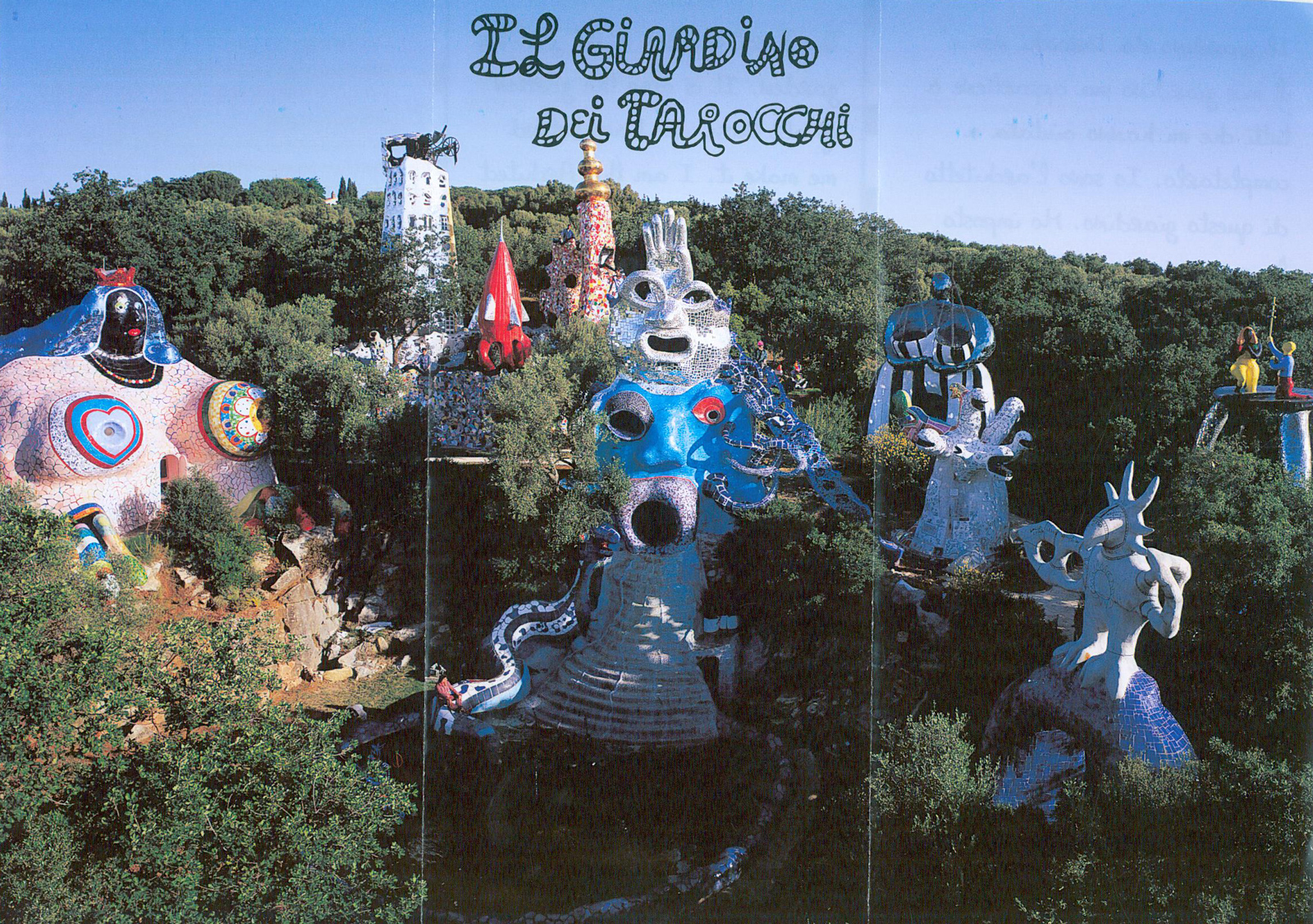

Fasten your seatbelts! You’ve arrived at Niki de Saint Phalle’s TAROT GARDEN, which she constructed from 1979 through 1998, and where she lived from the beginnings of the Garden until 1994. How does one make a Mannerist Home & Garden? Hmmm. Emphasize Feeling over Formality, but practice Fine Craftsmanship. Be aware of History, but give equal credence to your Personal Mythology. Accept that Life is a Precarious and Mysterious Event. Toss in a fistful of Exaggeration, and a dash of Fear. Add plenty of Unions of Opposites, along with a pinch of Eroticism. Find ways to express all of the above ideas in physical form, and you’re in the Mannerist Realm.

December 2016

Among all the avenues of self-expression available to humans, one of the most enticing has always been the building of a home and garden. For the mature visual artist in particular, modeling timber and stone and plant material into environments which give three-dimensional form to the artist’s peculiarities of imagination and character becomes a Great and Inevitable Challenge: a building project where the Psyche manifests itself as the Physical. And when the artist-builder is one who with his smaller-scaled works has ignored artistic convention, the results of his equally irreverent approach to home-making can, at least at the outset, infuriate his immediate neighbors. In a little while, I’ll guide you through the Italian homes and gardens of two fearless, but very different, 20th century artists: Tomaso Buzzi, and Niki de Saint Phalle.

Architect Tomaso Buzzi, based in Milan, was one of the most influential practitioners of avant-garde design in Italy. Born at Ticino, in 1900. Died at Rapallo, in 1981. In 1956 he purchased an ancient convent in Umbria, and for the next quarter century he built on the convent’s grounds a sprawling home and gardens, which he called his “Citta Ideale” or “Ideal City.”

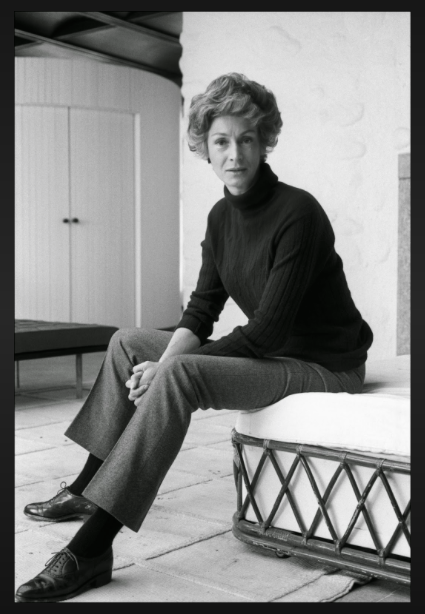

Artist Niki de Saint Phalle, Born at Neuilly-Sur Siene, France in 1930. Died at La Jolla, California in 2002.

Her “art happenings,” when she fired a rifle at her paintings and sculptures, made her a notorious figure on the international art scene in the early 1960s. By the mid 60s, her enormous, colorful sculptures of women, known as her “Nanas,” had brought her even greater fame.

Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi

But first: a sizable detour, as I explain the evolution of my own house-and-garden-making, which I present to illustrate to my Readers who aren’t of the house-building persuasion that, no matter how expansive or modest the design programme, when the aim is to devise a home and garden which will offer something beyond comfortable shelter and conventional resale appeal — when the homebuilder’s hope is that her refuge will also become a piece of livable art — the design process becomes interesting and perilous.

Most custom-made homes begin as dream fragments, decades before blueprints are made or ground is broken. I began drawing house plans when I was five. My first memorable effort included an unsettling glass-floored living room, suspended over an active stream (and no, I hadn’t at that early stage heard of Fallingwater).

For nearly five decades I was a typically rootless American. Never feeling that I’d found HOME, I lived in an assortment of places. A Levittown original; a Tudor revival; a Victorian pile; a Sixties split; a Bay Area studio; a crumbling railroad apartment; a “luxury” condo; a 200-year-old cider mill. I’d formed definite opinions about each: had kept a list of their good parts, and of their parts to forget.

I was born in Northern California, raised on the East Coast, majored in architecture at Massachusetts College of Art, prepared for a publishing career at the Radcliffe Publishing Procedures Course, founded my own publishing management business when I was 27, and foolishly endured a long and ill-founded marriage. When I was 49, I wised up, left the marriage, and also shuttered my business. Distraught and unmoored, I then worried to my father about all the NEW ways in which I might yet fail. But his reply to my litany of anticipated failures was always the same: “Life is short! What haven’t you done that you’d still like to try? Well then: DO it!”

Certain that such self-indulgence would be insane, as well as being the opposite of my Yankee’s-approach to finance, I nevertheless began to follow my father’s advice, and rather than gradually work my way up the Bucket List, I began with top-most task: that

of designing and building my own home.

I knew that to live the way I wanted, I’d need a tranquil, beautiful landscape around me. I imagined sleeping inside of a lantern that was suspended from great wooden beams. I calculated that I needed only four rooms (along—of course—with two full baths), all organized to follow the sun’s daily path. I wanted glowing shoji screens, and generous light to counteract my Norwegian melancholy. I wanted a huge, warm hearth. I wanted halls that teased and rooms that satisfied. I wanted a house of glass that revealed no secrets. And since, in middle years, I’d found that gardening meant HAPPINESS, I wanted my home to function as the gazebo at the center of the lovely, low-maintenance gardens I’d finally figured out how to grow.

I filled sketch pads, each page confidently crammed with these separate dreams. But while I drew tall windows and bookshelves, and high rafters and secret inside-peeking-places, the

graceful Palladian proportions that I could FEEL were not transferred to paper. I became discouraged: my hopes for a small but grand home would never be achieved.

One weekend I fled to my sister, who nursed my heart, which had been broken by things far worse than architectural failure. Pamela,

grasping for something to distract me, said “I think you’ll like seeing Frank’s,” and called to ask the architect who’d designed the renovations for her house if he’d give me a tour of his own home.

As I entered Frank Warner Riepe’s place—huge, airy, complex, cerebral … and oddly situated in a conventional suburbia— I saw a replica of Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s striking but utterly unsittable tea-room chair and felt comfortable nonetheless. Here was someone for whom architectural history, and light-games, and DELIGHT were living things. He GOT it!

The next week Frank sent a postcard: “It was nice to meet you…let’s talk again.” I remembered the wrongness of the watery living room of my childhood design, pawed through my piles

of magazine clippings and unsuccessful sketches, and finally bowed: to properly build my home, I’d have to surrender my draughting chair.

Over the next several months, I bombarded Frank with house plans, collages, and essays. He asked to see the books I read, the art I planned to hang. I told him that I love geometry and serene Renaissance squares, Japanese varnished wood, reflections, my grandfather’s ink rendering of the Petit Trianon, rosy colors, white boxes, and raw stone. I regaled him with tales of New Hampshire’s brutal chills and powerful winds. I told him that, somehow, I manage to shatter everything, and so this new home of mine had to be unbreakable.

Having dumped this tangle of information upon Frank, I went to Italy for a month; the job of deciding the form of my house was now his! Designing the next stage of my life was still a problem, however. But one afternoon as I wandered through Lorenzo de Medici’s palazzo in Florence, my problem was solved. As I studied the cornice of that building, the arches and angles and rhythms of its classical architecture transformed themselves into mental doodles of chairs and benches and tables. By the time I’d traveled to see my artist friend Jill Carlson De Carli in Venice, I’d drawn an entire portfolio of wrought iron garden furniture, which I named the “Lorenzo Line.”

My Lorenzo Arm Chair was the first piece that I designed. Hand-hammered depressions are in the seat; they cradle almost ALL sizes of buttocks.

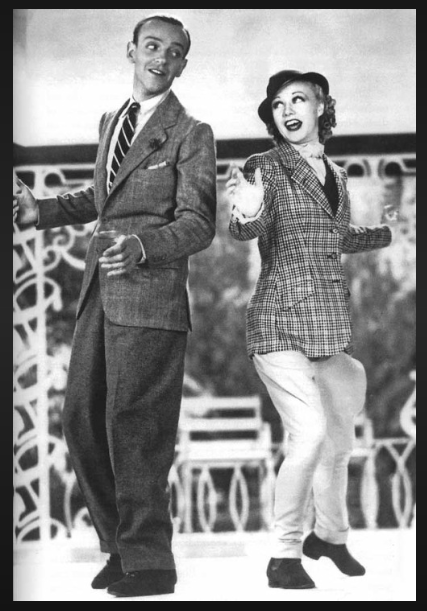

I returned to America, eager to find a blacksmith who’d make my furniture, and also prepared to begin what I expected would be the endless process of revising house plans with Frank. Instead, Frank presented me with a few, powerful drawings. I’d once told him that everything I love is deceptively simple…like Fred and Ginger dancing.

Fred & Ginger, TOP HAT: 1935. They’re dancing to Irving Berlin’s “Isn’t This a Lovely Day (To be Caught in the Rain).” Sublime.

And with functionality and artistry already fully joined, Frank gave me Astaire and Rogers with his very first design proposal. My seemingly-austere refuge was to be compact—with a footprint 20 feet wide by 56 feet long; and its roof peaking at 25 feet—jutting out of its south-facing slope, like a ship slicing through a wave. The crisp white clapboard exterior would give a nod to the rectitude of New England’s meetinghouses, while the house’s over-scaled windows — facing East, South, and West — would flood the wood-accented interiors with natural light.

A simple metal roof to repel ice and snow. Foot-thick walls to keep me warm. Study and exposed trusses of Douglas Fir. A massive, Earth-Mother fireplace. Huge double-hung windows, topped with smaller windows, marching down each long side.

Seen from different vantage points, a house of indeterminate scale: “How BIG, or small, is that house, anyway?”

Sliding shoji screens, surrounding a sleeping loft. A main living space with a route for circular-pacing around the chimney: kitchen to Great Room to library hall, to kitchen again.

The refinements would continue: Frank’s favorite verb became “agonize” as he described how he worked to mold all of my design preferences into a coherent whole, one which was both practical and elegant. And when any portion of his working drawings began to feel a bit too predictable (Frank would become exasperated with what he called my weakness for the “Relentless Square”), he’d throw me a literal curve or two, by designing circles of dark slate to counteract the linearity of the blonde oak floors…

…or by drawing an absurdly-sensuous but somehow perfectly correct bank of windows to overlook the front porch (my UPS man thinks these windows resemble a grand piano, and so must signify that a musician lives within…) .

A division of labor evolved. Frank did form, structure and specs: all the beefy and serious stuff. I chose colors, appliances, cabinetry, hardware and surface finishes; planned how I’d furnish each room, designed objects (an armoire, a hefty fireplace screen, a 7 ½ foot tall pyramidal vitrine), and later was responsible for making daily site visits during the 2-year-long construction phase.

My Pyramidal Vitrine was built by Neil Ritter. I chose silk curtain tassels to use for the door-pulls.

Once Frank’s authoritative working drawings had been completed, I thought things must well underway. But as I then began to interview local contractors, I was met with intractability. Although New Hampshire’s cadre of builders agreed that Frank’s working drawings were the most thorough they’d ever seen, I witnessed much head-shaking. My basic premise—that of a big-feeling-but-small-square-footage-house was, to them, incomprehensible. E.F.Schumacher’s 1973 treatise, SMALL IS BEAUTIFUL, was never-read or long-forgotten, and the tiny-and-small-house movement which is now fashionable hadn’t yet gained momentum.

“Why don’t you build a 3-bedroom Cape?” “Don’t build this as a one-bedroom house: it’ll never sell.” “I don’t understand this design…why does it have foot thick walls?” “ Those big retaining walls on both sides of the house are ugly.” “Why does the living room have such a high ceiling?” “What are shoji screens?”

But finally, I found the Cutter Brothers—Dave and Kevin: second-generation contractors who, upon seeing Frank’s working drawings, rubbed their hands with glee at the “FUN” they’d have, hand-crafting such an unusual little house. Over the construction phase, my first job was to oversee the clearing and reshaping of the land. My second task was to make the daily site visits. Apart from Debbie Desmarais ( the mason who built my massive granite fireplace ) at every step along the way, I was the only woman on site. Once the Cutter brothers and their crew saw that I actually could read the working drawings, and they also understood how greatly I admired their technical skills, the build-out became a joyful process.

I’ve lived in my home for many years now, and each of my visitors remarks that time spent here is good for the soul. Outside, my gardens have expanded and matured…

My house and gardens cover 2 acres. The remaining 3 acres of my property — hilly woodland, wetlands, and a babbling brook — have been left wild, as habitats for mammals, birds & reptiles.

…and are domesticated by groupings of my furniture.

Perhaps the most satisfying result is that these rooms which were so carefully planned to reflect my personality and to serve my needs have nevertheless also developed interesting qualities of their own. I inhabit a light-box, whose exterior and interior windows over the course of every day filter, diffract and capture Nature’s light in never-repeating patterns.

This house imposes a welcome ship-shapeness and a serenity upon me and all those who visit. And happily, contrary to the usual occurrence of an architect and his client becoming estranged after the lengthy process of Design/Build, Frank Riepe and his splendid wife Marilyn have become part of my extended family.

Over time, I’ve begun to feel that, just as a custom-tailored suit of the finest fabric becomes more and more supple with years of wear, these walls and I have fitted ourselves to each other in the most graceful and comforting manner.

After this long digression — a detour which I hope has now given those Readers who’ve never built themselves a home and garden just a taste of how complex a process this is — we’ll look at two surprising Italian properties, each of which took over 20 years to create. And as you learn about these extraordinary homes, bear in mind my saga of small-house building, and then multiply my efforts a thousand-fold: you’ll get a better notion

of how truly Herculean were the creative labors of Tomaso Buzzi, and Niki de Saint Phalle.

Onward….to Italy.

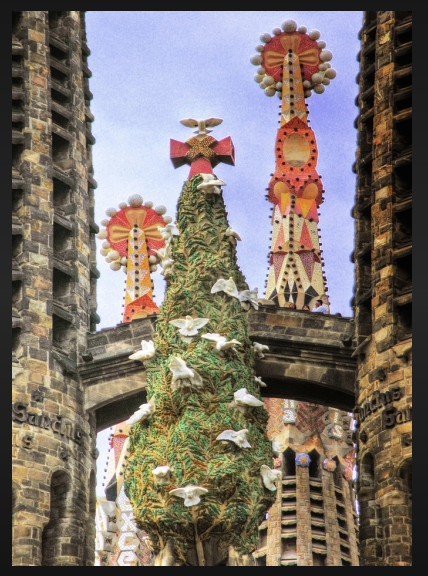

In early May of 2014, as I explored Bomarzo and Villa Lante, two eccentric Italian gardens in Northern Lazio ( both created in the mid 1500s in the Mannerist Style) , I was told about the existence of some modern counterparts, created during the late 20th century: gardens whose iconoclastic natures echoed those of their late-Renaissance predecessors.

Onwards from 2014, a growing sense of Unfinished Business plagued me: it became clear that I had to return to Italy to learn about a particular pair of Modern Mannerist gardens: Tomaso Buzzi’s La Scarzuola, and Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden. I needed to see for myself how these two artists who possessed very different sensibilities had each reshaped small parcels of the Italian countryside into places where fantasy was given solid and permanent form.

As I later began to research these new gardens, I mused that they’d been influenced by the same invisible and anarchic Italian Design-Sprites who for centuries seem to have been busy cross-pollinating and provoking the imaginations of many of those garden-makers who’ve toiled to make the convention-defying landscapes which are especially prevalent in West-Central Italy.

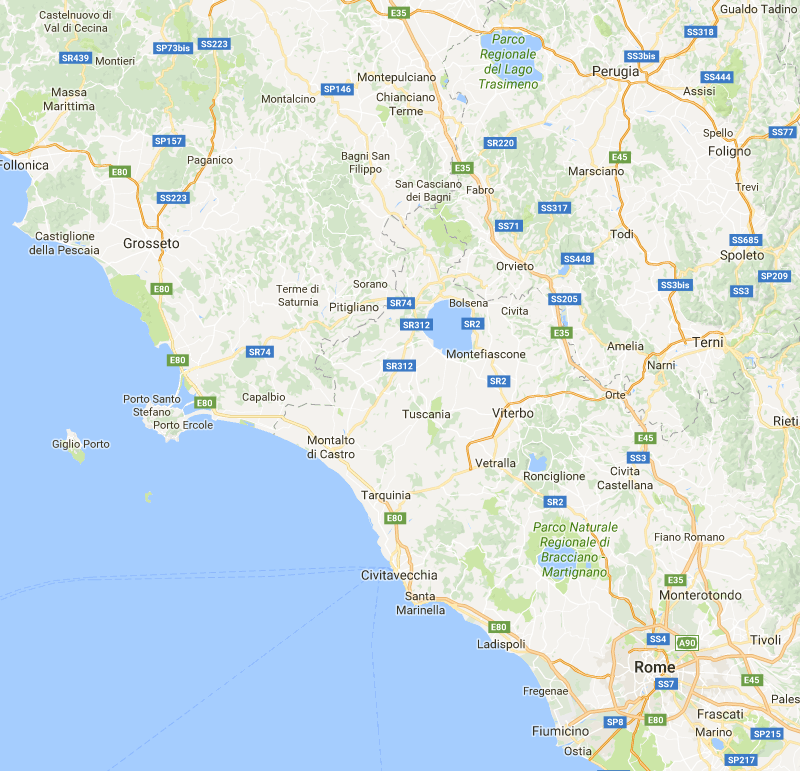

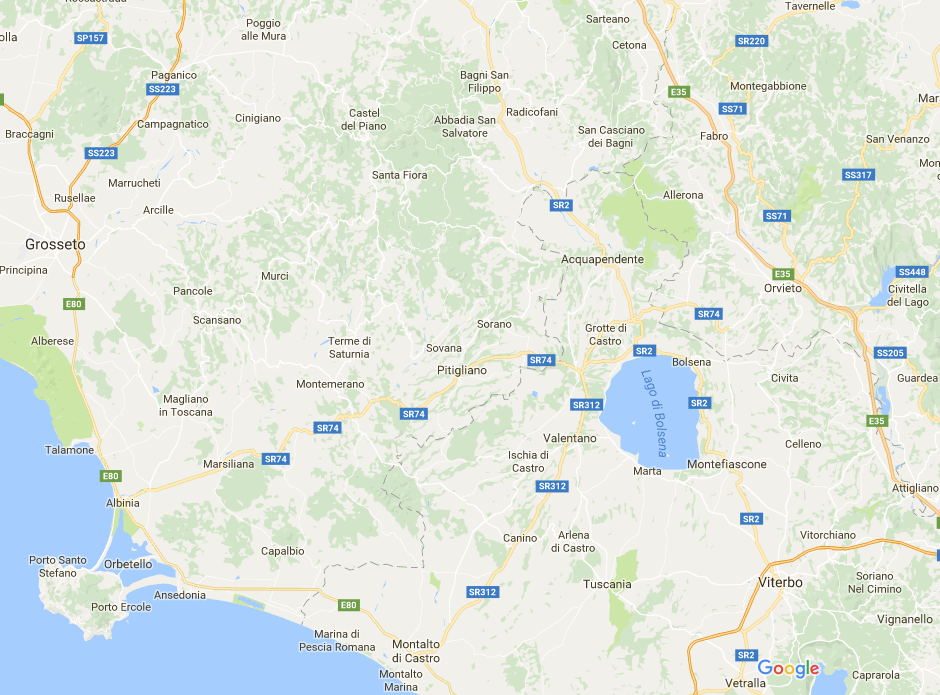

My garden-travels during July of 2016 were to Northern Lazio, Southernmost Tuscany, and Western Umbria

When I composed my Armchair Traveler’s Diary about the gardens I’d visited in 2014 — titled “Two Mannerist Gardens in Northern Lazio, Italy” — I began by attempting to define the nebulous meaning of Mannerism, and so, with today’s Diary, I won’t repeat that lengthy art-history lesson. For my extra-studious Readers who need memories refreshed, here’s the link to that article:

I used this photo of myself in the mouth of the Ogre at Bomarzo, as the lead for that article on Mannerist Gardens. You can be certain that Niki de Saint Phalle’s HIGH PRIESTESS in her Tarot Garden is a direct descendant of Bomarzo’s Ogre.

As always, when getting to rural Italian locales threatens to become especially gnarly for this solo-traveler, I turn to Valentina Grossi Orzalesi, co-owner of the custom-crafted-tours company, One Step Closer ( headquartered near Florence: www.onestepcloser.net ) . Prior to my July 2016 visit to Rome, I requested that Valentina once again book for me her best — and my favorite — Rome-based guide, Dr.Vannella della Chiesa, along with her driver Anacleto…both of whom had so ably led me to Bomarzo and Villa Lante, in May of 2014.

And, having during my 2014 trip to Italy discovered my Perfect Roman Hotel, there was no reason to think for more than a split-second about once again reserving myself a room at the Hotel Donna Camilla Savelli ( www.hoteldonnacamillasavelli.com )

in Trastevere. Note: You can find a complete report on that Hotel in my Diary titled “My Recipe for a Stress-Free Week in Rome.”

For nine days this past July, the Donna Camilla Savelli was my comfy home-base: a quiet refuge, run by gracious professionals, in a setting of confidently understated luxury.

In future Diaries I’ll report on the other Italian gardens I visited (Villa Farnese at Caprarola; Castello Ruspoli at Vignanello; Vatican Gardens; Gardens at Villa Medici; Michelangelo’s Cloister at the Diocletian Baths; The Papal Gardens at Castel Gandolfo). And NO, for those who are heat-sensitive, July is clearly NOT the best month for your Italian adventures. With age, however, I am finding myself immune to the discomforts of hot weather…see, one’s dotage does has its advantages.

The VIEW over the Hotel Courtyard, and the rooftops of Trastevere, from my room at the Donna Camilla Savelli, on late afternoon of July 7, 2016.

After having spent most of June in England ( where it had rained nearly every day ), on the 5th of July I arrived in Rome … just as Italy began to be clobbered with waves of humidity and high 90s temperatures. But no matter; being able to ditch my too-frequently-worn Hunter Wellies for a pair of sexy, amazingly-supportive Munro gladiator sandals felt like Liberation…

….and so, while the Romans around me groaned about the stifling warmth, I rejoiced at the novel sensation of feeling hot breezes upon my bare toes. Every morning, after a restorative night’s sleep in my air conditioned hotel room, I donned my comfortable footwear, pulled on a simple sleeveless shift, plopped a hat on my head, grabbed my cameras, and prepared to walk for many miles…either along the City’s cobbled streets, or over acres and acres of countryside gardens. My habits of wearing simple attire and of getting constant exercise — adapted to whichever country and whatever climate greet me — allow me to dwell upon the wonders around me while I eliminate most of the travel discomforts which come from being slave to one’s luggage, and from spending too many days in couch-potato mode. Ultimately, the KEY to remaining presentable while wandering for 40 days and 40 nights (the total duration of my summertime 2016 trip) is to pack only as much clothing as can be squeezed into a single, compact suitcase, and then to be conscientious about doing hand-laundry in one’s hotel bathroom, each and every evening! To go clubbing, or to go scrubbing? I always opt for soap and sink.

But first, before we begin our visits to this Diary’s Modern Mannerist Gardens, please reacquaint yourselves with my Italian travel guides, Vannella and Anacleto.

Steady Driver Anacleto, and Esteemed Guide Vannella, at the entrance to the splendid gardens of Villa Farnese at Caprarola

( built in the mid 1500s, and which we’ll explore at length in a future Diary) .

The two gardens we’ll soon discover could be visited by a Rome-based visitor over the course of one, VERY long day, but such an itinerary would end up being more work than fun. Besides, such an arduous schedule would leave no time for enjoyment of a leisurely lunch… and sampling the specialties of small restaurants in the Italian countryside is an essential pleasure.

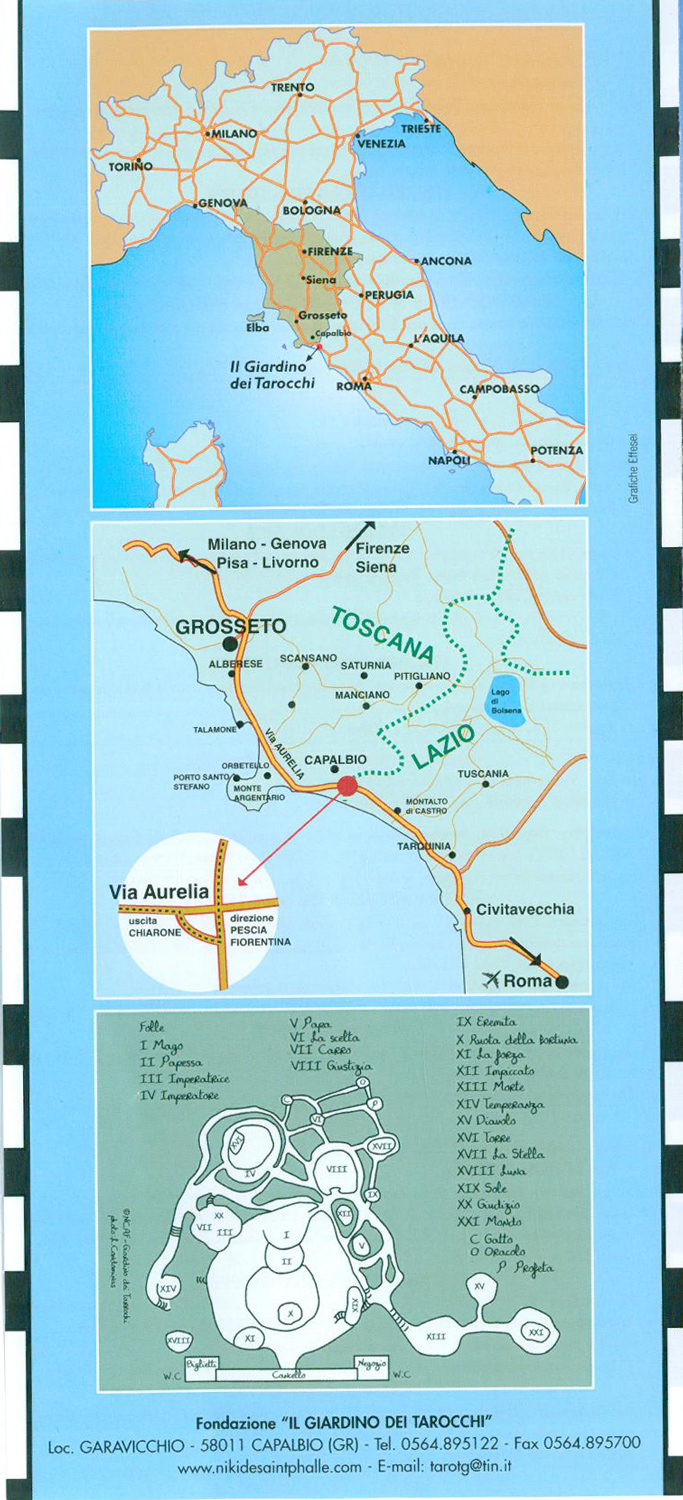

The Tarot Garden is outside of Capalbio,

which is near the seacoast, and the island village of Porto Ercole.

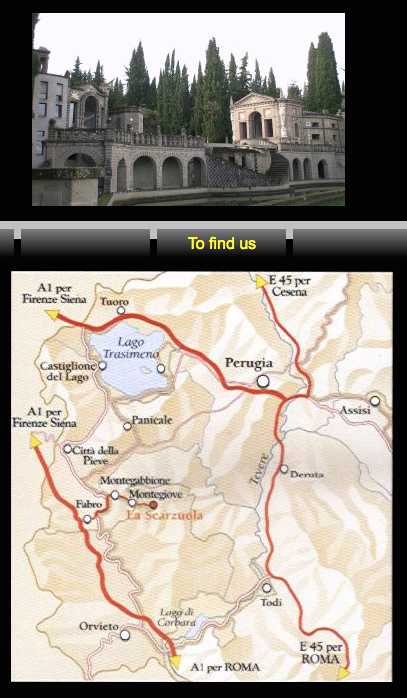

La Scarzuola is further inland, to the north, outside the hamlet

of Montegabbione (too small a place to register on this map):

in the mountains above the town of Orvieto.

Driving from Rome to Capalbio takes 2 hours (assuming that Rome’s traffic isn’t gridlocked; sometimes extricating one’s self from Rome takes far longer than planned). Driving from Rome to Montegabbione takes about 2 ¾ hours.

A more detailed map of our destinations. This map does indicate the location of Montegabbione: which is north of Orvieto, and then Fabro… on Strada Statale (state highway)# SS71…not much more than a serpentine, mountain road (if you’re prone to motion-sickness, remember your Dramamine). The Tarot Garden is much easier to find, at the exit for Capalbio, just off European Route # E80.

I visited La Scarzuola on July 13th, and the Tarot Garden on July 11th. We’ll begin now in reverse chronology, with La Scarzuola.

Wednesday, 13 July 2016

A visit to: La Scarzuola

05010 Montegabbione, in the Terni Region of Southern Umbria

phone & fax: 011-39-0763-837463

website: www.lascarzuola.com

email: info@lascarzuloa.com

Open throughout the year, by appointment only.

Arranging a visit to La Scarzuola demands persistence.

Guided tours are available throughout the year, for groups of no fewer than 8 visitors. Tours are given either in Italian, or in English, and you must specify your desired language. When you email La Scarzuola to request a tour, you’ll receive their reply in Italian, but the gist of the message will be you’ll

have to wait until enough other people have signed up to reach that 8 person minimum. And once you’ve finally set foot on terra firma, don’t expect to wander freely over the grounds; full access to the complex of buildings and gardens is not allowed, and a firm time limit of 90 minutes is enforced.

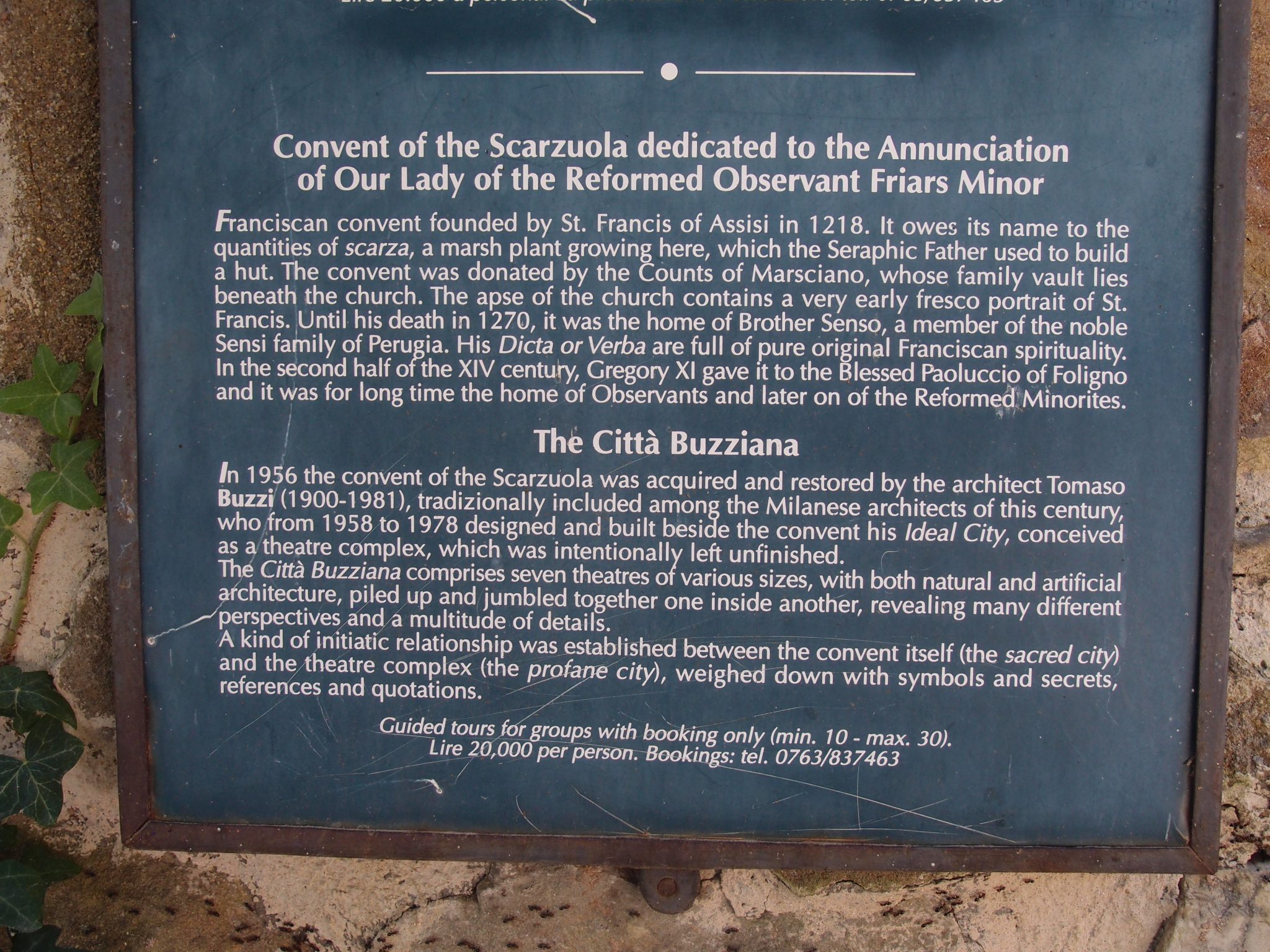

La Scarzuola’s quadruple-language Visitor’s Guide offers the following history:

“This Franciscan convent, founded in 1218 by St. Francis of Assisi, who planted here a bush of bay and roses and caused a spring to gush forth, owes its name to a marsh plant, the SCARZA, which the Saint used to build himself a shelter. The apse of the church still bears an early 13th century fresco depicting the Saint in levitation.”

Saint Francis of Assisi — although not shown aloft here — was known as a holy man who could hover 1.3 meters above the ground.

Turning our backs to the Church, we look toward the entry gate, and see some of the other English-speaking folks who will be joining the tour group.

“In 1956, the convent complex was acquired by Milanese architect Tomaso Buzzi (1900 – 1981 ). Between 1958 and 1978, he planned and erected his own IDEAL CITY beside the convent, envisaged as a “theatrical machine.” Buzzi’s city, including as many as 7 theaters, culminates in the Acropolis, a piled-up wealth of buildings comprising numerous archetypes, empty inside and provided with as many compartments as a termites’ nest, which provide many surprising vistas.”

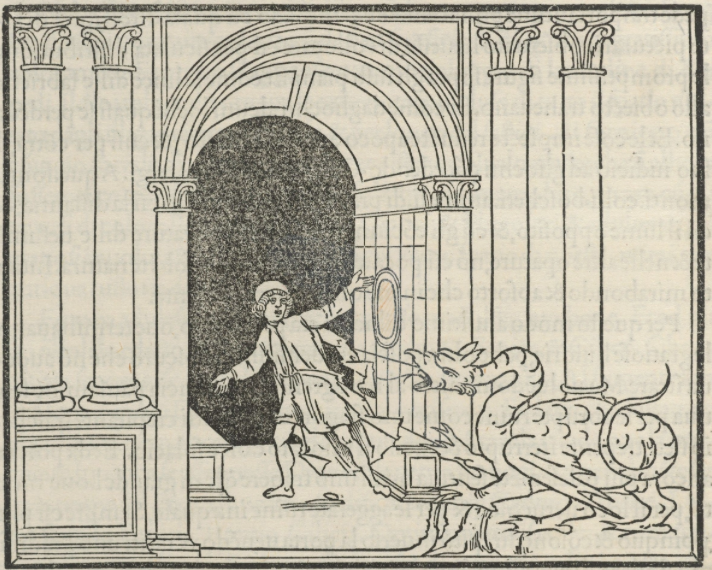

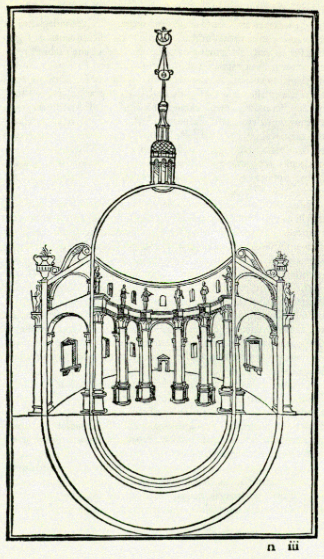

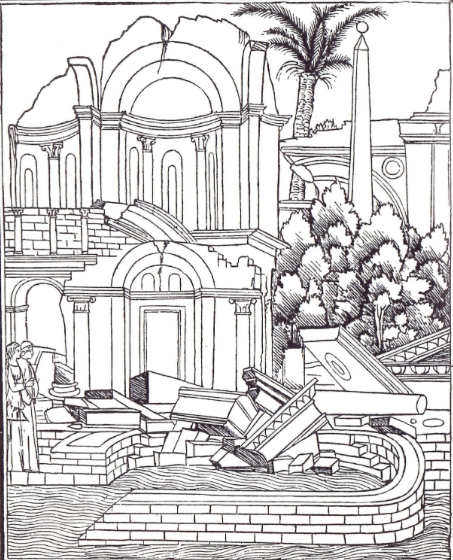

“A relationship is thus established between the convent (the sacred city) and the theatre buildings (the profane city), both laden with symbols and secrets, references and quotations. Inspired by Francesco Colonna’s HYPNERTOMACHIA POLYPHILI [ translated: “Poliphilo’s Strife of Love in a Dream.” This was a romance, illustrated with 168 exquisite woodcuts, and first published in Venice in 1499. ] , the style that best interprets the licence of this design is neo-mannerism: stairs used in all directions, the deliberate disproportion of some parts, a few monsters, the heaping together of buildings and monuments, amounting to surrealism, something of the labyrinth, something evocative, geometric, astronomic, magic.”

Phew! While we’re still chewing all the syllables in

“Hypnertomachia Polyphili,” let’s get up to speed about the book which so greatly influenced Tomaso Buzzi’s design for La Scarzuola. In short, the tale describes Poliphilo’s dream within a dream. He first dreams that after Polia, his beloved, has rejected him he wanders into a forest, where he encounters the requisite number of monsters and fair maidens, and also enters many buildings, which are (of course) built in a dizzying variety of styles. Poliphilo then dreams he’s awakened, but he has actually descended into a second dream, which is populated with nymphs, deities, and more bizarre buildings. The outcome of Poliphilo’s dream within a dream is familiar: like Orpheus, he finally finds Polia (his Eurydice), revives her from near death with his kiss, but, just as he’s about to take firm hold of his beloved, she evaporates. The vivid woodcuts of the “Hypnertomachia” clearly made an impression upon Tomaso Buzzi…

…and Colonna’s narrative provided Buzzi with the framework for a bricks-and-mortar encyclopedia, in which small-scale models of the architectural forms that Buzzi most favored were juxtaposed with images which sprang from ancient myth, and from Buzzi’s own preoccupations and fears. He called La Scarzuola his “Petrified Dream.”

Perhaps the final irony of La Scarzuola is that Tomaso Buzzi meant for his fanciful buildings to be eroded by weather, and for his densely-planted gardens to be neglected by humans. From the outset, Buzzi had planned a Future Ruin. All was to be defeated by the passage of time: smothered by brambles and vegetation and ultimately forgotten. Speaking of “the wondrous power of NON FINITO,” Buzzi fashioned his Ideal City using sub-par building materials and methods which had no prospect of enduring, and by the time of Buzzi’s passing, many of the structures on the property had already gone into deep decline.

However, upon Buzzi’s death in 1981, La Scarzuola went to his nephew and only heir, Marco Solari.For the past 36 years, Solari has made it his life’s work to repair

(or to build anew: at the time of his death, Buzzi still had not constructed some of his designs for La Scarzuola) most of the structures with higher quality materials: materials which replicate in every detail Tomaso Buzzi’s original drawings.

Unlike his uncle, Signore Solari has NO intention of allowing Time and Nature to destroy La Scarzuola … such is the prerogative of the Survivor!

I recently emailed Marco Solari to inquire if he has any vintage photos of his uncle’s living quarters at La Scarzuola. Unfortunately, no pictures of those rooms in their original state have survived (which would please Tomaso very well, I think). And, over the course of Marco’s several decades of making improvements at La Scarzuola, all residential spaces have been thoroughly remodeled.

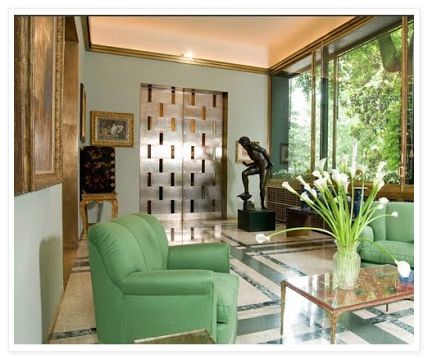

Before we begin our tour of the public spaces at La Scarzuola, I’d like to give you a little peek at some of the refined interiors and furnishings for which Buzzi was also known. From the 1920s until the late 1950s—when Buzzi then turned most of his attentions to the creation of his “retirement” home at La Scarzuola — Buzzi was one of Italy’s most in-demand taste-makers: as an architect, he was known for collaborating well with his fellow architects (an unusual attribute among that tribe). He was also a designer of furniture, glassware, and interiors. His clients included society’s highest-flyers: in Italy (the Agnellis, the Cinis, the Borlettis), and in America (where Hollywood royalty such as George Cukor sought his services). He also taught drawing at Milan’s Polytechnic University, from 1938 until 1954.

Milan’s Villa Nechi, which served as the setting for the film I AM LOVE (made in 2010), was built by Milanese architect Piero Portaluppi in the 1930s, and decorated by Tomaso Buzzi in the 1950s. Image courtesy of CINEMA STYLE blog.

Guided tours at La Scarzuola begin with a peek inside the ancient convent’s church, which was constructed in 1282 by local noblemen, on the site where Saint Francis (who died in 1226) had in 1218 used the local marsh plants to build his hut. As our group ( an uncomfortably large assemblage of at least two dozen visitors ) began to walk in single-file through the church’s warren of small rooms our guide reminded us to keep our elbows lowered and to move carefully past the jumble of precious artifacts. Throughout the entire 90-minute-long tour that day, I kept thinking how much more rewarding the experience would be if groups consisted of no more than ten visitors. With so much to see, and so little time allotted, most of my hour and a half at La Scarzuola became about trying to detach myself from the mob for just long enough to quietly observe my surroundings, and then to very quickly take photos to record my progress through the property. The following photos, in which I struggled to have as few people as possible appear, suggest a far more tranquil experience than the one I actually had. Given my druthers, I’d love to return to La Scarzuola for a solitary, day-long amble through this “Ideal City.” And even then, for this aficionado of architecture and gardens, my first day spent exploring and trying to understand the place Buzzi called his “autobiography in stone” would then demand a second day, and then a third. However, as a mere tourist, I had to settle for seeing as much as I could, despite the constraints.

So…our brisk Dog-Trot began: first through the gardens (which Buzzi created to cradle the Convent, which he called the “ Sacred City “ ) , and then father afield, to the literally theatrical “Citta Ideale” (which the architect built to represent the Profane).

Yes, in addition to our gregarious Guide, two friendly Dogs — to whom these Cities truly belong — showed us the way.

This older fella seemed very tired, but he was still game, and, with several long rest-stops, he finished the tour with us.

And this passage through yet another leafy tunnel makes us feel as if we’ve fallen down the Rabbit Hole, and into a Separate World.

A sense of near-claustrophobia, as Italian Cypresses tower over the walls of the Lily Pond’s Courtyard.

We pass through an opening in the garden wall, which is constructed of a patchwork of field stone, blocks, and concrete. Leaving the shady Garden, we follow a narrow dirt path which winds through a high hedge, and —WHAM — we’re confronted with the Main Ampitheatre of Buzzi’s Ideal/Profane City. This space was fashioned on the slopes of a natural ampitheatre, in the hillside below the Convent. Of the seven theatres in the Ideal City, the Ampitheatre, which seats an audience of 600, is the largest (the tiniest theatre accommodates only 10 people).

To the right of the Ampitheatre is Buzzi’s man-made mountain of reduced-scale depictions of famous pieces of architecture, with an Acropolis at the center.

Our Guide told me that La Scarzuola’s insurance policy forbids Tour groups from clambering through this intriguing warren of buildings at the Acropolis. The site is too fragile to survive daily poundings from hundreds of tourist-feet. And all of those stairways — some which lead to Dead Ends, or to Aeries — would be prime sites for tumbles and broken necks. But remember that Tomaso Buzzi built this Little World for himself and his guests: just imagine what FUN climbing over these architectural playgrounds would have been! Perhaps some day if I’m fortunate, I’ll be invited back for a private ramble, as the photographer who took the next three pictures was.

Atop the Ideal City: the Colosseum and a Roman Triumphal Arch. Image courtesy of Curious Places Blog.

To resume the chronicle of my July 13th visit:

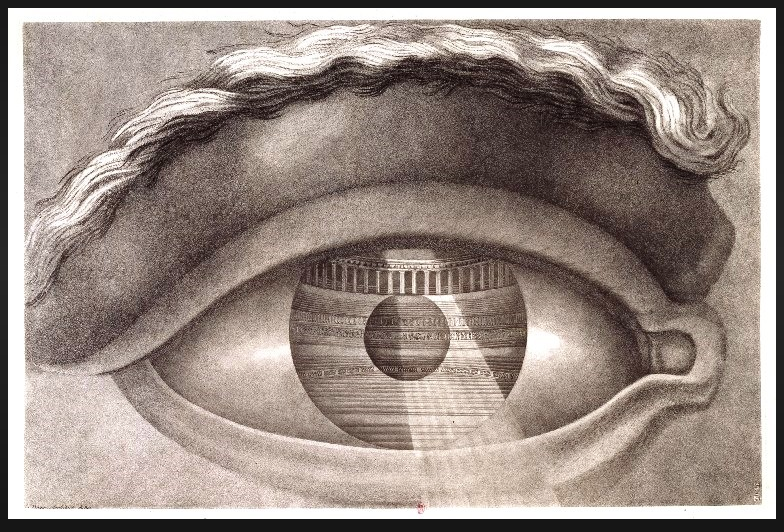

Tomaso Buzzi didn’t just do cover versions of the architecture of Antiquity. In the Ampitheatre, his Great Eye stage pays homage to

Claude-Nicolas Ledoux (born 1736, died 1806), a French visionary who also called his mostly-unbuildable designs “Ideal Cities.”

In the Ampitheatre, directly opposite the Great Eye, we see the gaping maw of Buzzi’s Ogre, which is a direct descendant of the 16th century Ogres, in the nearby Monster Garden of Bomarzo. [Note: Vicino Orsini’s Garden of Bomarzo, which he made with Pirro Ligorio and Simone Moschino in the mid-1500s, still haunts me, and ranks as one of the most magical, man-made, places on Earth. For a day at Bomarzo, the length of one’s visit there is limited only by the hour at which the sun sets.]

Our Guide and his Dogs next herd us out of the Ampitheatre, and down the hill, where we gather below and outside of the massive walls of the Ideal City.

A closer look at the Clock Tower, which I now realize was keeping accurate time. Our tour began at 11AM, and at this point only 35 minutes remained for the Tour…

Walls usually have Ears. Buzzi’s walls have EYES.

This City Wall detail shows how humble building materials—roughly-fashioned blocks and bricks—have been ingeniously assembled to form intricate, shadow-casting patterns.

While I’m studying brick-laying methods, I look up and am confronted by what seems to be a Monumental Goddess. We can safely assume that Tomaso Buzzi wasn’t a Leg Man.

Our Guide, waiting for the many stragglers in the Group to catch up, provides necessary Human Scale, by the Goddess.

Such attention to detail: to the left, see how blocks are stacked to suggest books. And what a beautifully-formed navel.

Behind the City walls, and adjacent to the Goddess, we spy an intriguing form: a Glass Cone, topped by a starburst. More about this Cone, in a bit…

I cast a final, admiring glance at this scene, which combines cobalt skies, green cypresses, crisp shadows, and the smooth concrete skin of our Goddess.

We continue our stroll, downhill.

The Massive City Walls are differently articulated,

all along the way. Within this portion of the Wall is the circular Court of Apollo, which is centered upon a giant, dead (and intentionally-dead, from the Start) tree, whose top-most branches you can see.

Between the City Walls and the freestanding Tower, we pass a massive retaining wall, and then head toward the lowest spot on the property.

But just as things at the Ideal City have finally begun to seem Rather Normal, we’re forced into the Mouth of a Sea Monster.

Once through the Sea Monster’s mouth, we find ourselves in a long, walled trench, which leads to yet another of Tomaso Buzzi’s homages to the flights-of-fancy of the French.

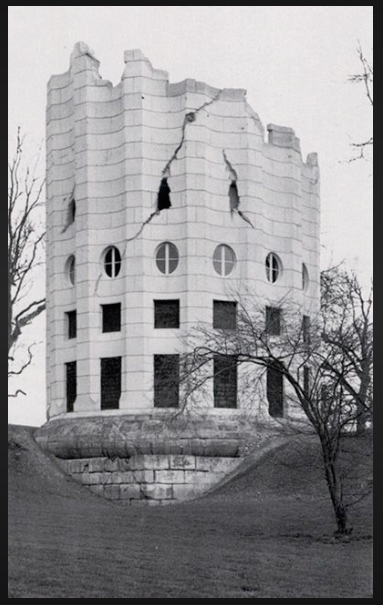

At the end of this trench is Buzzi’s interpretation of the famous Ruined Column which is part of Desert de Retz,

an exotic landscape garden, in Chambourcy, France.

The Ruined Column at Desert de Retz

was designed by visionary architect Francois Racine de Monville, and built in 1782.

A beautifully-formed passage through the base of the Ruined Column. The stairs lead uphill, to a portion of the Ideal City which we must still visit.

A young fellow (wearing a fabulous T-Shirt) and I both have the same idea: to get FAR AHEAD of the slow-moving cluster of Visitors that’s behind us.

Unfazed by the heat (the day was HOT, but nevertheless intoxicating because Umbria’s mountain air is so pure) my Trailblazer-companion ran up the columned pathway.

Halfway up the columned path, I paused to admire the outlying regions of the Ideal City, which we would soon explore.

At that same half-way spot, I turned to savor my views of the Ruined Column and the beautiful countryside.

Having reached the top of the columned path, my Tiger-Shirted Companion disappeared into the lower reaches of the Ideal City.

My solitude isn’t to last.

Behind me, I see our Guide, with the fastest-walking members of the Group, and the Golden Dog.

Placed at the top of the grassy slope is a crescent-shaped pool, which most commentators call Buzzi’s own smaller, and curvier, version of the Canopus Pool ( Emperor Hadrian’s enormous pool at his villa in Tivoli) .

La Scarzuola’s Great Pool, which is adjacent to the outermost, and lowest section of the Ideal City’s complex of 7 theatres.

Following is a single shot from a portfolio of pictures I took at Hadrian’s Villa, on May 17, of 2014. [ Note: My Diary-making is woefully back-logged. But I do plan to eventually publish a Diary for Armchair Travelers about the two Wonders of Tivoil: the 2000-year-old-remains of Hadrian’s Villa, and the almost-hanging-gardens of the nearby Villa d’Este, which were begun in the mid 1500s. ]

Emperor Hadrian’s Canopus Pool, in Tivoli, as I visited it on yet another of Italy’s scorchingly-hot days: on May 17, 2014.

Back now, to La Scarzuola:

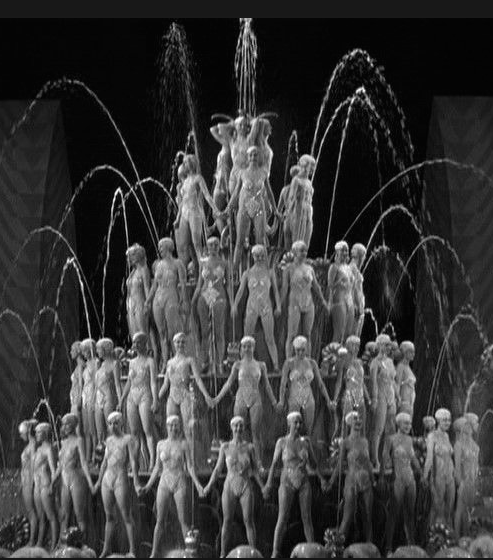

Although I’ve read nothing to suggest this, I like to imagine that Buzzi envisioned this Pool in his City of Theatres as the venue for a future Naumachia

[ Note: a mock naval battle, enacted with model ships] , or as the setting for a waterborne incarnation of a theatrical production . The first known such reenactment of a naval battle, for entertainment purposes, was given by none other than Julius Caesar, in 46 BC, Rome. What could be more in keeping with the fantastical, archaeological and theatrical spirit of La Scarzuola than to produce a bit of Drama in the Drink? Whether or not Buzzi actually contemplated such extravagant displays isn’t important.

What matters is this: when the appearance of a physical object — or atmosphere of a place — provokes free-association or creative thought in those who are viewing the object or place for the first time, then the Designer has doubly fulfilled his original mission. This is a point I was trying to make, at the outset of this Diary.

Detail of Double Stairs, which sweep down from an elevated stage. And behind these stairs is yet another of the Ideal City’s smaller theaters, this one a place of mirrors and reflections…which we’ll soon enter.

I mean REALLY: Don’t La Scarzuola’s Double Stairs just BEG to support a bevy of Busby Berkeley’s Ladies? Here’s a still from the 1933 film FOOTLIGHT PARADE. Jimmy Cagney.

Joan Blondell. Ruby Keeler. When you’re feeling glum, watch this movie….you’ll be chipper in no time.

Our group begins to file into the narrow corridor which leads to the small, poolside theatre which hides behind the Great Pool’s curvy, double stairways.

In groups of six, we’re allowed to briefly inhabit the theatre, while our Guide explains how mirrors are placed to reflect each member of the audience. So, with clock ticking, I sit,

take a couple of photos, and Reflect.

Then, taking advantage of a rare, unsupervised moment, I explore a warren of passageways that are behind the Mirrored Theatre.

One of the passageways takes me directly below the great, open-air stage of the Ampitheatre. I head toward light at the end of a dark tunnel, and looking outside, am rewarded with this view of the Ideal City.

In another basement passage, I find a locked gate, and peer out into the Ampitheatre and see the Ogre’s Mouth.

My Free-Ranging-Tourist-Moment over, I’m folded back into the Group, directed away from the Great Pool, and propelled into this claustrophic space: the circular Court of Apollo.

Our Guide, in the Court of Apollo. The shadow of the dead tree ( that’s rooted in

center-Court ) serves as a menacing clock hand.

This compact, columned space is adjacent to the Court of Apollo. At the far end, encased by an upward-swirling masonry lattice, is a glass-sided cone, which contains a golden, spiral stairway.

And inside of the glass-sided code are the Pythagorean Stairs, with steps that issue musical notes as people walk up them. Unfortunately, visitors are not allowed on the Stairs (but think of the tunes our feet could have played… )

Writing this now, five months after seeing La Scarzuola, I find that after having taken more time to reflect and do research, my attitude about my July 13th interlude at Tomaso Buzzi’s Ideal-and-Profane-City has undergone a significant change.

Upon first seeing La Scarzuola, delight is unavoidable. But, on July 13th, my delight was quickly replaced by frustration, as our too-large group of visitors was then hustled through only a portion of the property. Much of the closely-supervised 90-minute-long tour was thus unsatisfying: either I was wishing I could sit for longer than two minutes in the largest ampitheatre, or waiting for stragglers, or lining up to take a fast peek at another point along the circuit. Our Guide did his best to keep things cheerful —while moving us inexorably toward the Exit — but I became quietly discouraged: clearly, this limited look at La Scarzuola would make it impossible for me to understand the Essence of such a labyrinthian place.

But, through many years of travel, I’ve learned that it can be short-sighted to overemphasize my disappointments about the manner in which owners of an exceptional property choose to present it to the public. If, despite such disappointment, after my visit a Place still haunts me, I’ll review my photo archive, analyze my emotions,

and strive to better understand that property’s inherent character.

When I choose to travel with companions, once we’re arrived at our destination, my friends or guides have all learned not to be offended by my need for solitude as I explore. I don’t want to immediately be told facts and figures about a garden, or a building. After I’ve traveled a far distance to reach yet another of the World’s Wonders all that matters at first is having some tranquility and time…the better to deeply observe my surroundings. Under ideal touring conditions, I follow this procedure: I stand on one spot, and then slowly pivot a full 360 degrees, because often the grandest views — or the most telling details — are behind me. And then, because good architecture and good gardens must be experienced without haste, I inch my way deeper into the site. But I sympathize with La Scarzuola’s Guide, for whom the practicalities of moving his clusters of visitors from one point to another require steady, forward motion.

In circumstances like these — where the fragility of a site severely limits the ways in which non-VIP visitors may explore it — it becomes my Diary-Maker’s mission to describe the site as it might be experienced, under optimal conditions.

Apart from the necessary words of caution from its current owner, in the most concrete terms, Tomaso Buzzi’s Ideal City itself also warns: “Do NOT Touch!” Rough masonry, articulated blocks, and sharp stones have been mortared together to create a tapestry of form and texture, but La Scarzuola’s sensuality is visual and intellectual, as opposed to tactile. There are no walls of velvety marble; no expanses of glazed tile to invite touching: running one’s hands across the rustic surfaces of the Ideal City’s buildings would cause abrasions, at the very least.

La Scarzuola is a feverish dream, made solid: an architectural mashup where Buzzi joined archetypes from his professional life, symbols borrowed from myth, and images dredged from his subconscious. Buzzi’s autobiography-and-dream in stone — culminating in the Ideal City’s Theatrical Hive — sets the stage, figuratively and literally, for the ultimate form of self expression: that of giving free play to one’s imagination. La Scarzuola’s curious structures all invite Movement (both physical, and spiritual): up stairways, along passages, through temples. And all routes lead, inevitably, onto those stages. And what’s an empty stage but just a pause? It’s a space which is asking to once again become animated, through the power of human imagination. The now-quiet stages of Buzzi’s “Theatrical Machine” offer settings which suggest to each Visitor that he too can embark upon his own journey of creative thought and action.

At La Scarzuola, we see an artist’s brave and extravagantly radical feat: somehow, Tomaso managed to construct a multi-dimensional map of his own mind. I’m glad I’ve finally been able to come to an understanding about Buzzi’s purpose, which has made my visit to his improbable, “Ideal City” in the Umbrian hills completely worthwhile.

Monday, 11 July 2016

A visit to: Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden

Pescia Fiorentina

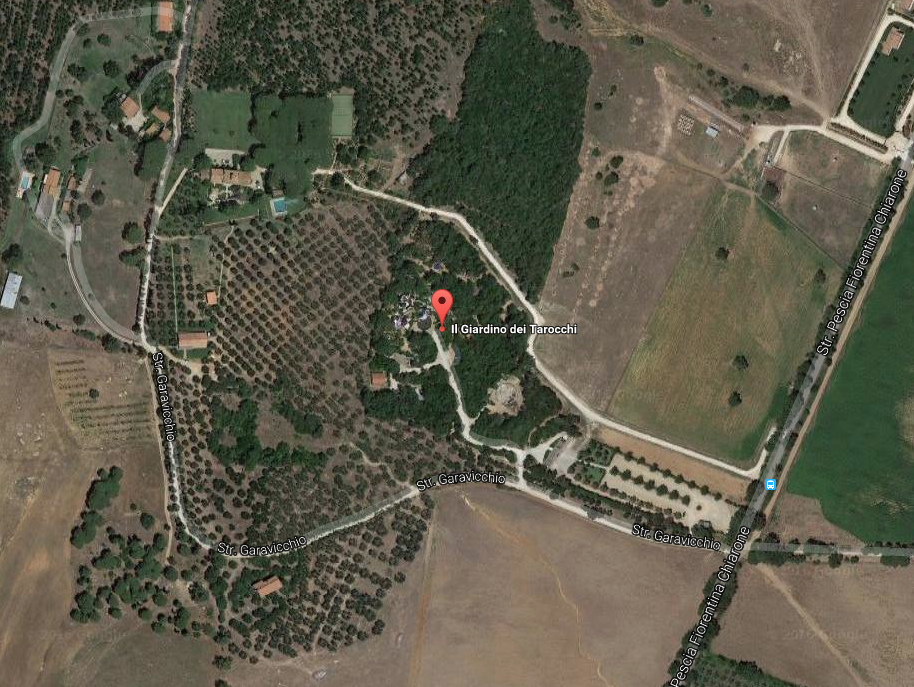

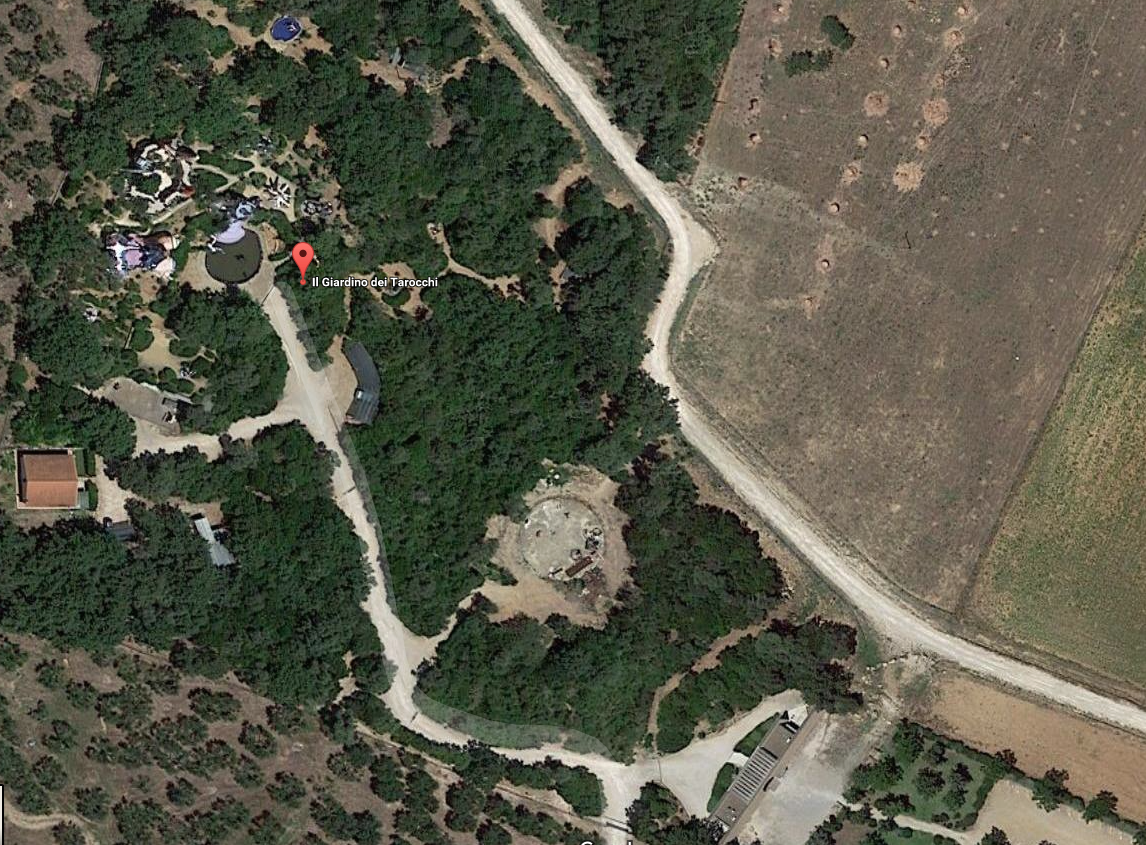

Garavicchio, 58011 Capalbio

Province of Grossetto (on the border of Southern Tuscany,

and Northern Lazio )

phone: 011-39-0564-895122

website: www.nikidesaintphalle.com

email: tarotg@tin.it

Open: April through Mid-October, Daily

Hours: 2:30 PM — 7:30PM

Unlike La Scarzuola’s designer Tomaso Buzzi, (who longed to be evanescent, and thus left behind no written accounts of his life) Niki de Saint Phalle, the designer of the Tarot Garden, spent most of her 72 years making a record — with words, paintings, sculptures and structures — of her passage through life.

The circumstances of her birth ought to have ensured Niki smooth sailing. Catherine Marie-Agnes de Saint Phalle (no wonder she soon called herself “Niki”) was born near Paris, to an aristocratic French father, and a rich American mother. But, from the get-go, things went haywire. In one of her several memoirs, Niki wrote:

“When do you start to rebel? In the womb? At five? At ten? I was born in 1930: a Depression Baby. While my mother was expecting me, my father lost all their money. At the same time, she discovered that my father was having affairs. She cried everything into her pregnancy. Later, she told me everything was my fault. I’d brought trouble.”

Finding that life would be less expensive in America, the family (Niki had 4 siblings) soon resettled in New York, where her father was eventually able to mend his finances. As soon as Niki graduated from high school, she escaped, and for the next several years she would earn a living as a model.

And at 18 Niki secretly married Harry Mathews, a childhood friend. In short order she became the mother of two children, Laura and Philip. By 1953, the Mathews family had moved to France. But much as she adored her husband and kids, the strains of marriage and motherhood —which Niki taken on without any

sound emotional underpinnings — had broken her. After a spell at a psychiatric clinic in Nice, Niki declared that,

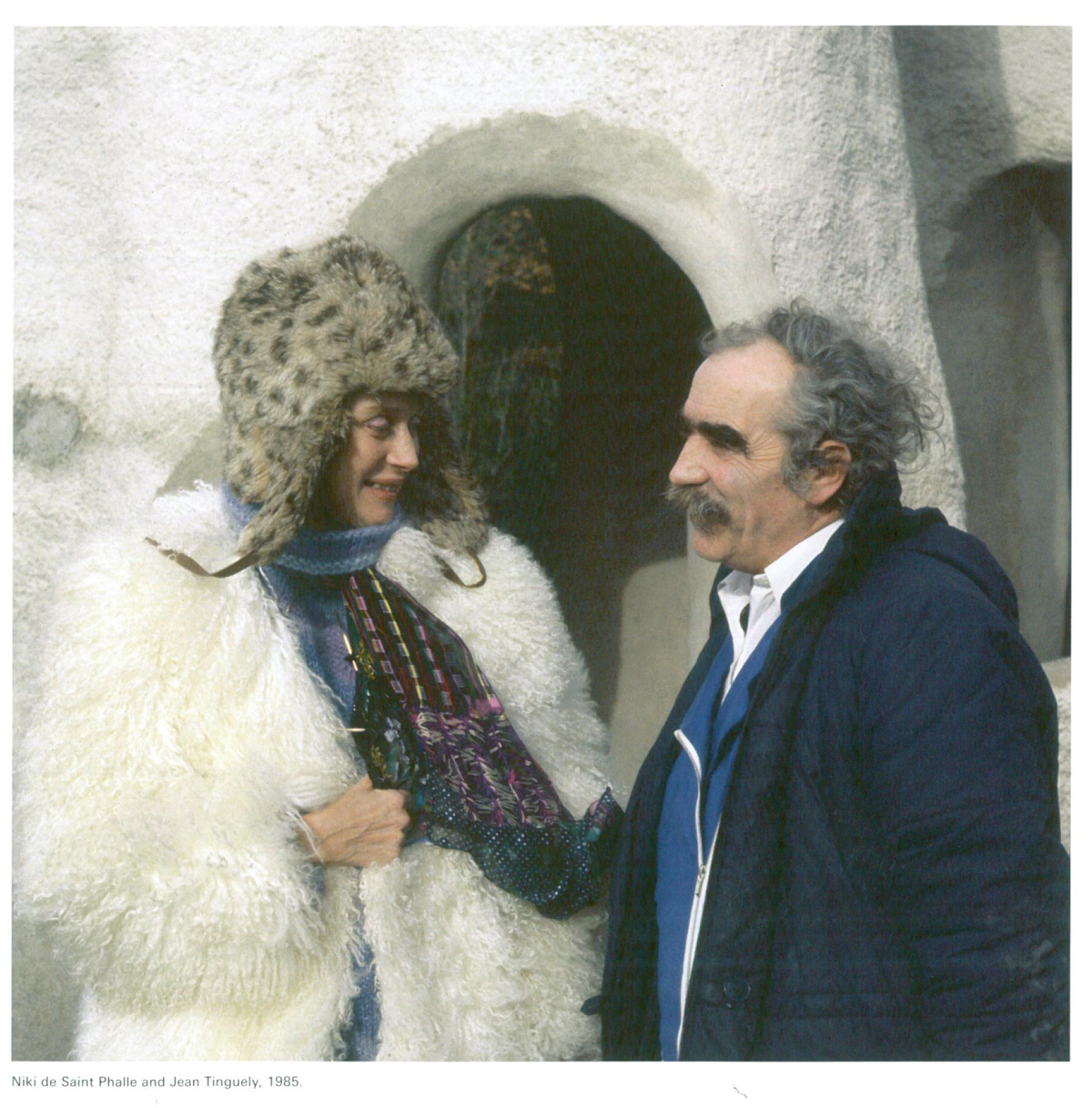

to regain her sanity, she must devote all of her energies to being an artist. By 1955, Niki had become deeply involved with Europe’s circle of New Realist artists (which included the Swiss sculptor Jean Tinguely, who, in 1971, would become her second husband). In 1960, she finally left her young family: her guilt at abandoning her children gnawed at her for the rest of her days.

In 1961, at age 31, Niki de Saint Phalle began work on her “Shots” series. Always attracted to the sculptural, she built large backdrops—which often resembled altars—

to support reliefs that included sacred and profane images. She then tucked containers filled with paint between the sculpted elements. And finally, a thin layer of white plaster was applied to all surfaces. Then, summoning photographers to record the event, Niki (and friends) fired guns at the murals: bullets, hitting hidden pockets of paint, then caused her paintings to “bleed.”

By 1963, after all of that gunfire, Niki had gotten a good measure of rage — rage which she eventually explained was due to her father having sexually abused her when she was 11 years old — out of her system. She wrote: “Suddenly the pain was past. I stood there and did figures of joy. Perhaps they came from everything I’d really had enough of.” She became obsessed with a new and positive image; that of the life-giving power of the Feminine. Using wire, and fabric, she began to make large dolls.

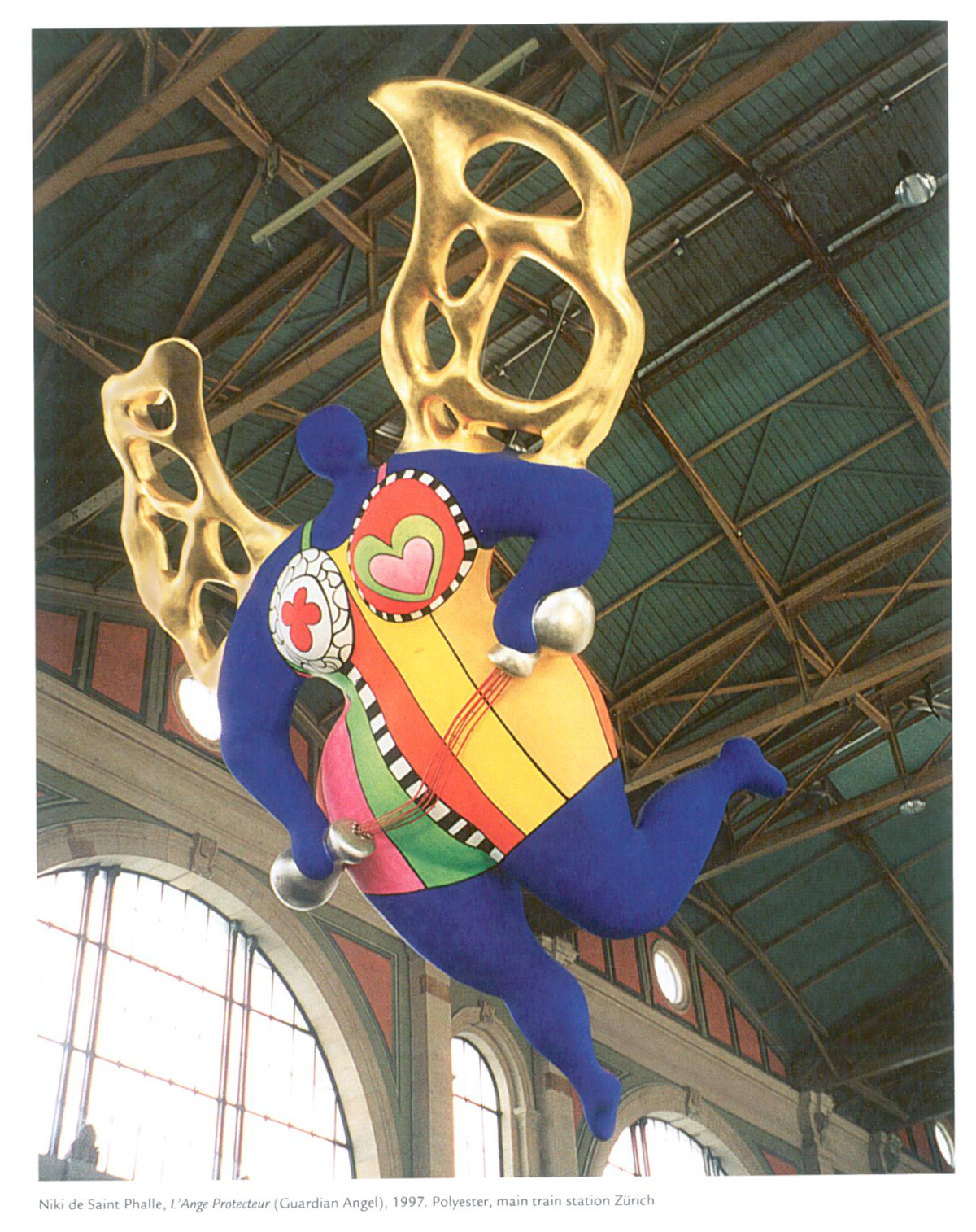

In 1964, Niki needed to make her Goddess statues larger, and, seeking a material suitable for open-air display, she began using polyester resin, which she painted in gay colors. These voluptuous statues, which seemed always about to pirouette, or to take flight, became the “Nanas” which gave her worldwide fame. But Niki’s new medium of polyester would eventually be her undoing: the fumes which polyester gives off during processing severely damaged her health. For the remainder of her life, she suffered from constant and nearly crippling illnesses.

Niki de Saint Phalle’s L’ANGE PROTECTEUR.

This enormous sculpture of painted polyester, which weighs 1.2 tons and is more than 36 feet high, hangs in the rafters of Zurich’s main railway station, and was made in 1997 by Niki to guard travelers. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

While she worked non-stop to make her Nana sculptures, Niki continued to be haunted by an old dream. In her introduction to the Tarot Garden she writes:

“In 1955 I went to Barcelona. There I saw the beautiful Park Guell of Gaudi. I met both my master and my destiny. I trembled all over. I knew that I was meant one day to build my own Garden of Joy. A little corner of Paradise. A meeting place between man and nature.”

In 1978, while Niki was in Switzerland recovering from a pulmonary abscess, she crossed paths with Marella Agnelli…

…who she’d met many years before, when both young women had been working in New York City. Niki described to her old friend her unfulfilled dream of building a garden, one in which the Cards of the Tarot were transformed into giant sculptures. Marella, thinking of a neglected 14 acre parcel of land in southernmost Tuscany which was owned by her brothers, arranged an introduction. At their meeting, Niki unleashed all her charm and enthusiasm: the “brothers just kept on saying YES!” Before the brothers

quite knew what had occurred, they had given her the land. Niki found herself in possession of the ultimate canvas: an arid hillside, where groves of olive trees grew atop Etruscan ruins…and with views over farmland, all the way to the Tyrrhenian Sea.

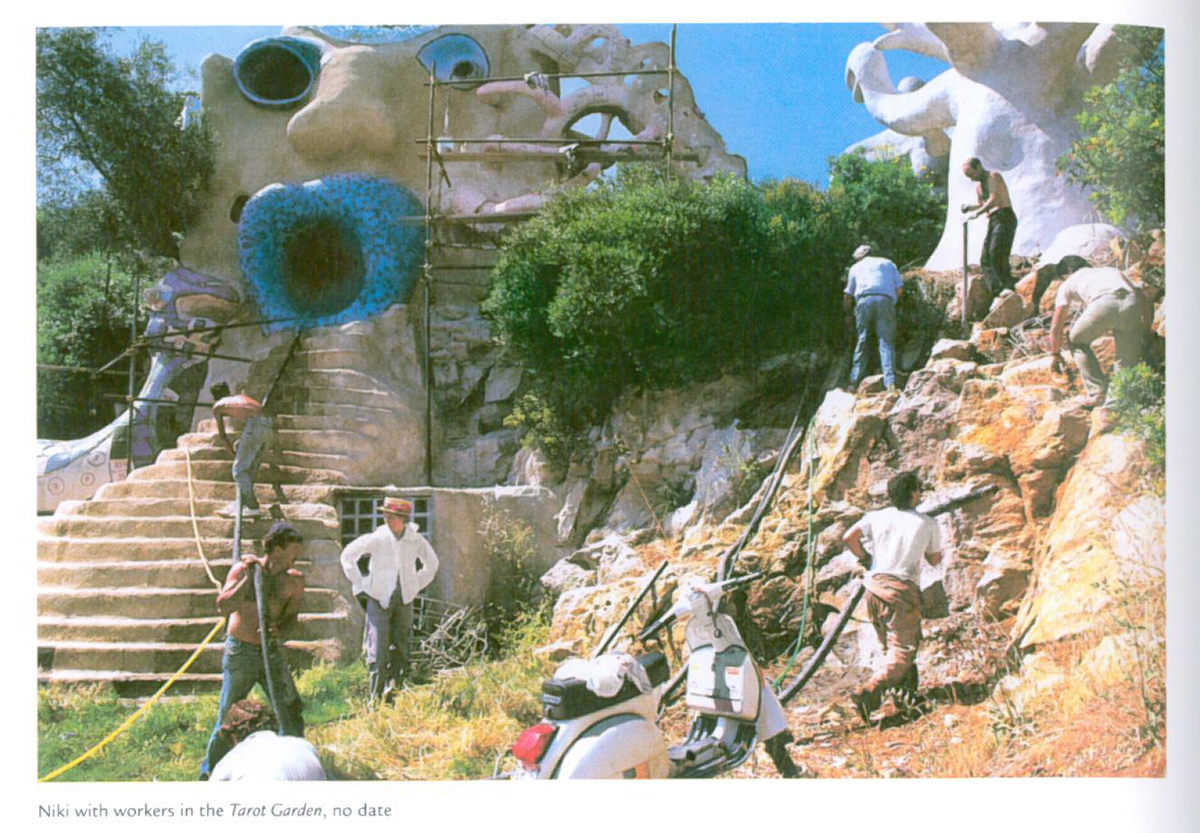

Continuing her account of the Tarot Garden’s beginnings, Niki wrote: “Twenty four years later I would embark on the biggest adventure of my life: the Tarot Garden. It was built in Tuscany on the property of my friends Marella Agnelli and [Marella’s brothers] Carlo and Nicola Caracciolo. They had approved the original model which I kept changing. The Tarot Garden became much bigger than I had originally intended. There was no deadline and I worked in complete freedom. To finance the garden I made a perfume and multiples [ of the Nana sculptures ] .”

“As soon as I started the Tarot I realized it would be a perilous journey, fraught with great difficulties. I was struck by Rheumatoid Arthritis and could barely walk or use my hands. Yet I went on. Nothing could stop me. I was bewitched.”

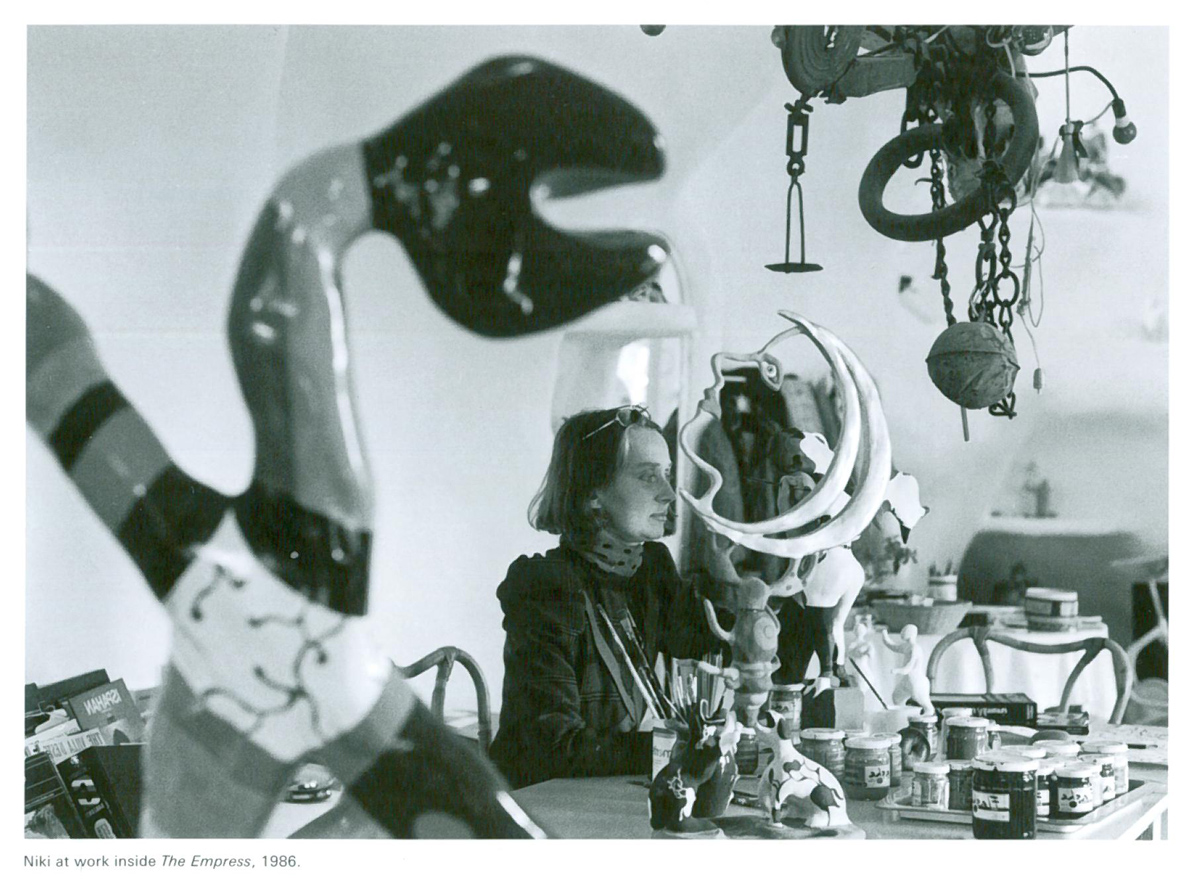

“I also felt it was destiny to make this Garden no matter how great the difficulties. I made the card of the Empress my home and she became the center of the Garden. It was where I met the crew, ate my meals, and made the models for the remaining cards.”

“I lived alone in the ‘Sphinx’ which was what we nicknamed the Empress. Total immersion was the only way to realize this Garden.”

“The Tarot Garden is not just my garden. It is also the garden of all those who helped me to make it. I am the architect of the Garden.

I imposed my vision because I could not do otherwise.”

“This Garden was made with difficulties, love, wild enthusiasm, obsession and most of all faith. Nothing could have stopped me.”

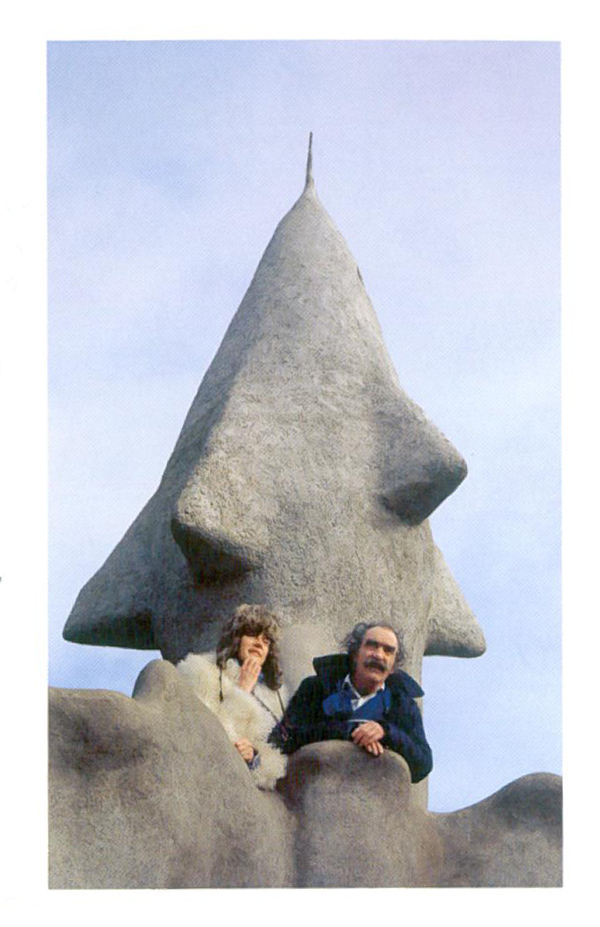

Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, in 1985, as the Tarot Garden was being constructed. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

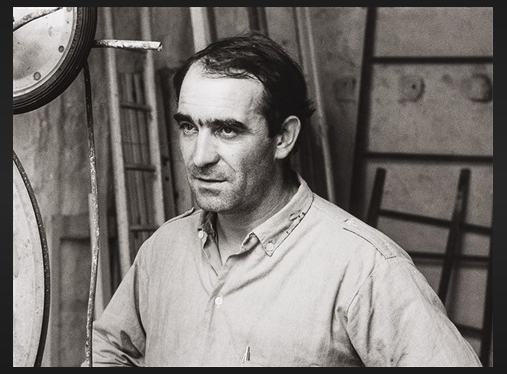

Jean Tinguely was Niki’s long-time artistic colleague (from 1955, until Tinguely’s death, in 1991) , as well as her second husband. Their marriage was unconventional, loving, and often fraught with drama and pain. Although they’d cohabited for many years previously, by the day of their wedding, Jean had already been living for some time with another woman, who soon after his marriage to Niki became pregnant with his child. But, regardless of their volatile emotional relationship, Tinguely was always the most ardent supporter of Niki’s artistic endeavors. A sculptor and master welder, Tinguely constructed half of the metal forms which supported the Garden’s larger structures.

Jean Tinguely, Swiss painter and sculptor.

Born 1925, Died 1991. Niki, as his widow, oversaw the creation of the Jean Tinguely Museum in Basel.

The Ticket Office and Entrance Gate to the Tarot Garden is austere to the point of being forbidding. In her Visitors’ Guide Niki writes: “I asked my friend Mario Botta to make the entrance to the Garden in contrast to what was inside. Mario made a masculine fortress-like wall of local stones which marks clearly the separation of the world without and the world within. The wall symbolizes for me a protection like the dragon who protects the treasure in fairy tales.”

In 1979, Niki began to oversee clearing the land, pouring foundations for the largest structures, and the laying of stone for pathways. In 1981 Niki rented a nearby cottage, and hired many local residents, who became her full-time assistants. By 1983, the shell of the Empress had been completed, and Niki moved in. For the next seven years, the Empress became her full-time home and studio. By the early 1990s, Niki’s always-precarious health had worsened. In 1994, her illnesses having become severe, Niki left Italy and

moved to San Diego, CA, where she remained for the rest of her life. But even though far-removed from her beloved Tarot Garden, Niki made certain that the work which continued there was dictated solely by her decisions and designs. And per the terms of her Will, the portions of the Tarot Garden which were incomplete at the time her passing will now remain unfinished, in perpetuity.

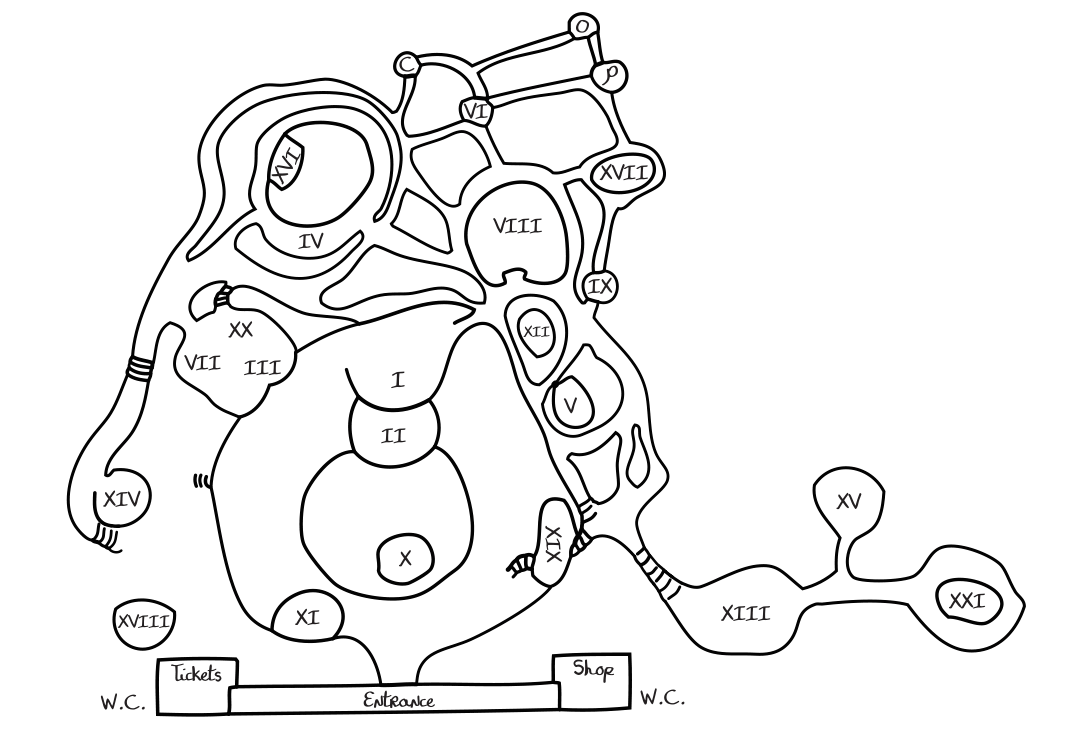

Let us begin our tour of the Garden, which you’ll discover in the same sequence as that of my visit, on July 11th, 2016.

Key to Tarot Garden structures and sculptures. Note: locations are listed here, in the same order that Nan visited them.

I—The Magician.

II—The High Priestess.

X—Wheel of Fortune.

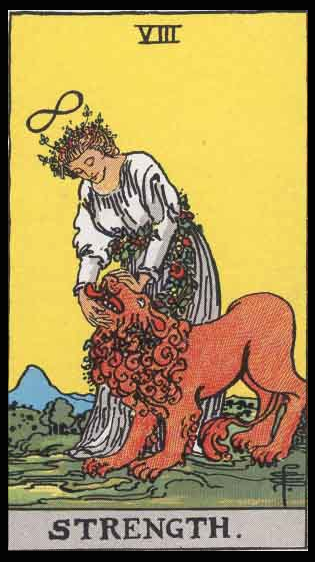

XI—Strength.

XVIII—The Moon.

XIV—Temperance

III—The Empress.

VII—The Chariot (inside the Empress) .

XX—Judgement (inside the Empress) .

IV—The Emperor.

XVI—The Tower (part of the Emperor).

VI—The Lovers.

O—Oracle. P—Prophet. XVII—The Star.

VIII—Justice.

IX—The Hermit.

XII—The Hanged Man (inside the Tree of Life).

V—The Hierophant.

XIX—The Sun. XIII—Death.

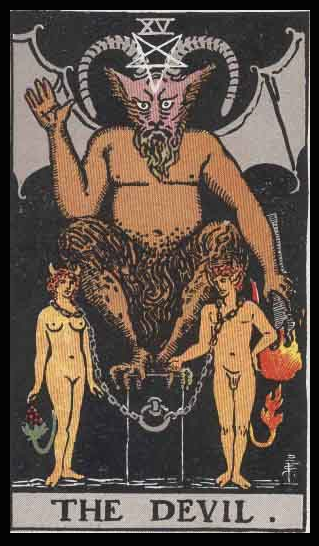

XV—The Devil.

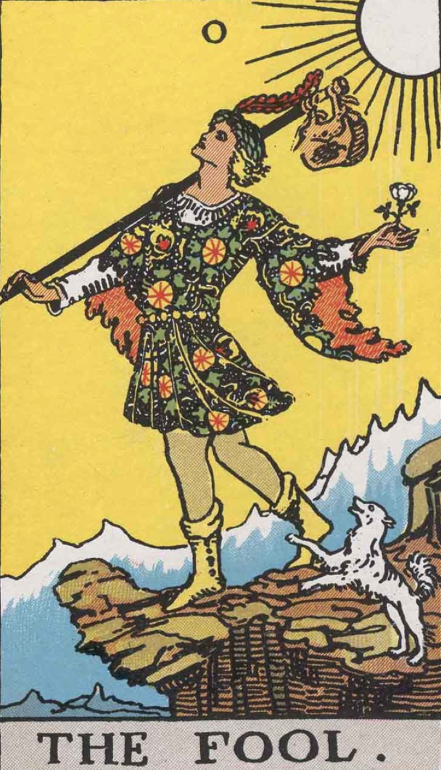

XXI—The World. Note: The Fool (not marked on this map, is

located near The World).

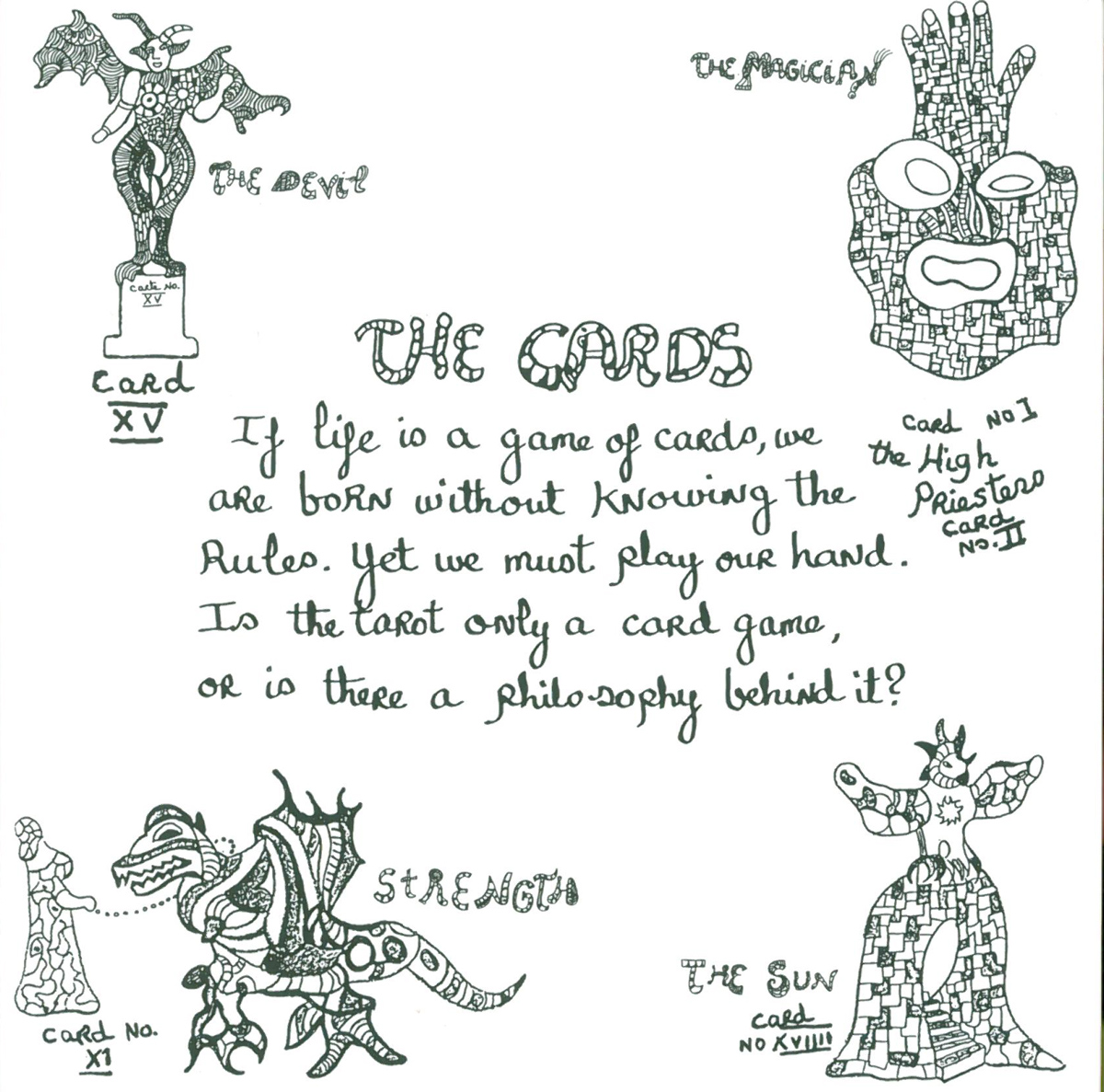

Niki de Saint Phalle wrote of the Tarot: “I am convinced that the cards contain an important message. The origins of the tarot are shrouded in mystery. It seems that the high priests of ancient Egypt transmitted their secret knowledge by means of pictorial symbols and that these symbols were the twenty-two Major Arcana of the tarot pack. The tarot has given me a greater understanding of the spiritual world and of life’s problems, and also the awareness that each difficulty must be overcome, so that one can go on to the next hurdle and finally reach inner peace and the garden of paradise.”

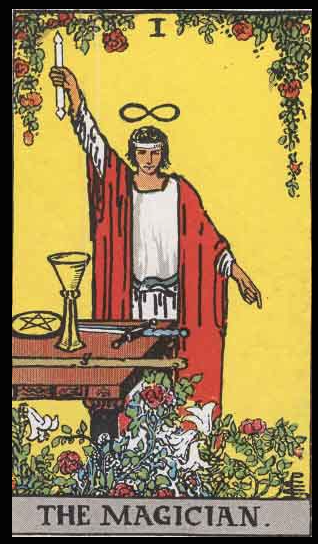

The Magician, Card I of the Tarot Deck. Note: All card images in this Diary are from Rider-Waite Deck (circa 1910) , and are the same cards to which Niki de Saint Phalle referred as she designed her Garden.

The Magician. Per Niki: The Magician is “the great trickster. For me, the Magician is the card of God, the creator of the universe. It is he that crated the marvelous joke of our paradoxical world. It is the card of active intelligence. Pure light, pure energy, mischief, and Creation.”

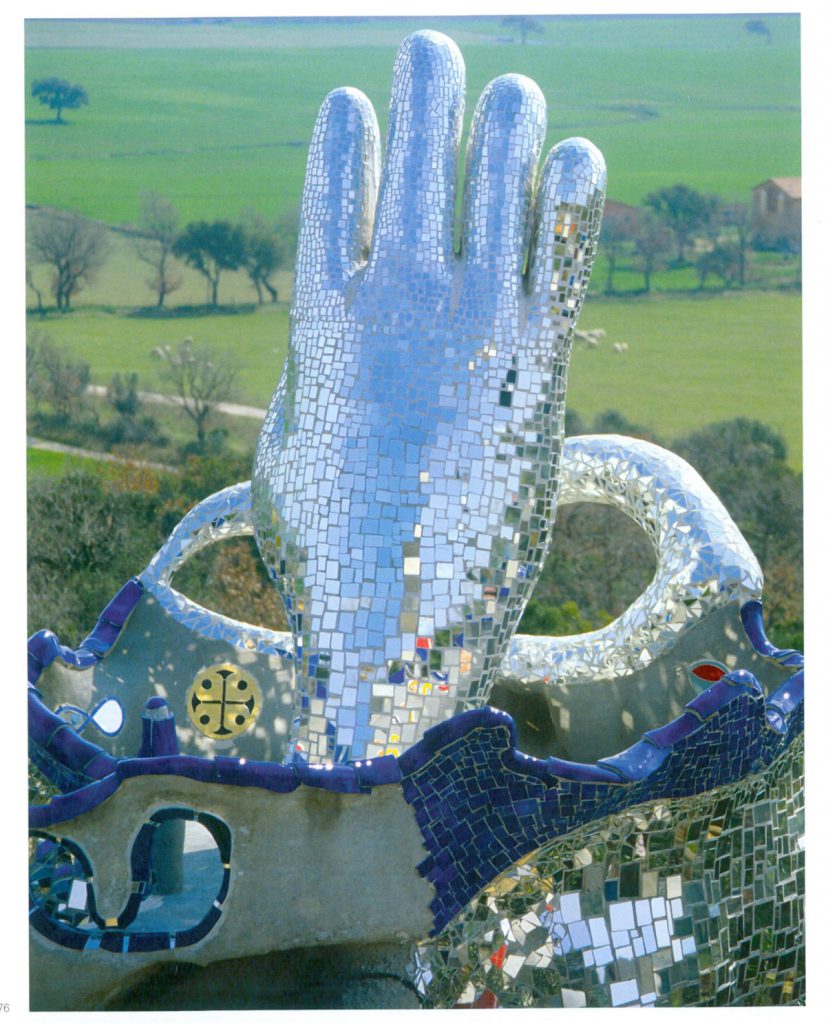

The silver head and hand of The Magician are balanced on top of the blue head of the High Priestess.

The Hand of the Magician, rear view. The open palm of the hand faces the sea. This photo was taken when the decoration of the Hand was nearly complete. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

The High Priestess, Card II of the Tarot.

Per Niki: “The High Priestess of Intuitive Feminine Power. This feminine intuition is one of the keys of wisdom. She represents the irrational unconscious with all its potential.”

The High Priestess (in Blue), with Magician (in Silver),

and the Wheel of Fortune (metal fountain in foreground)

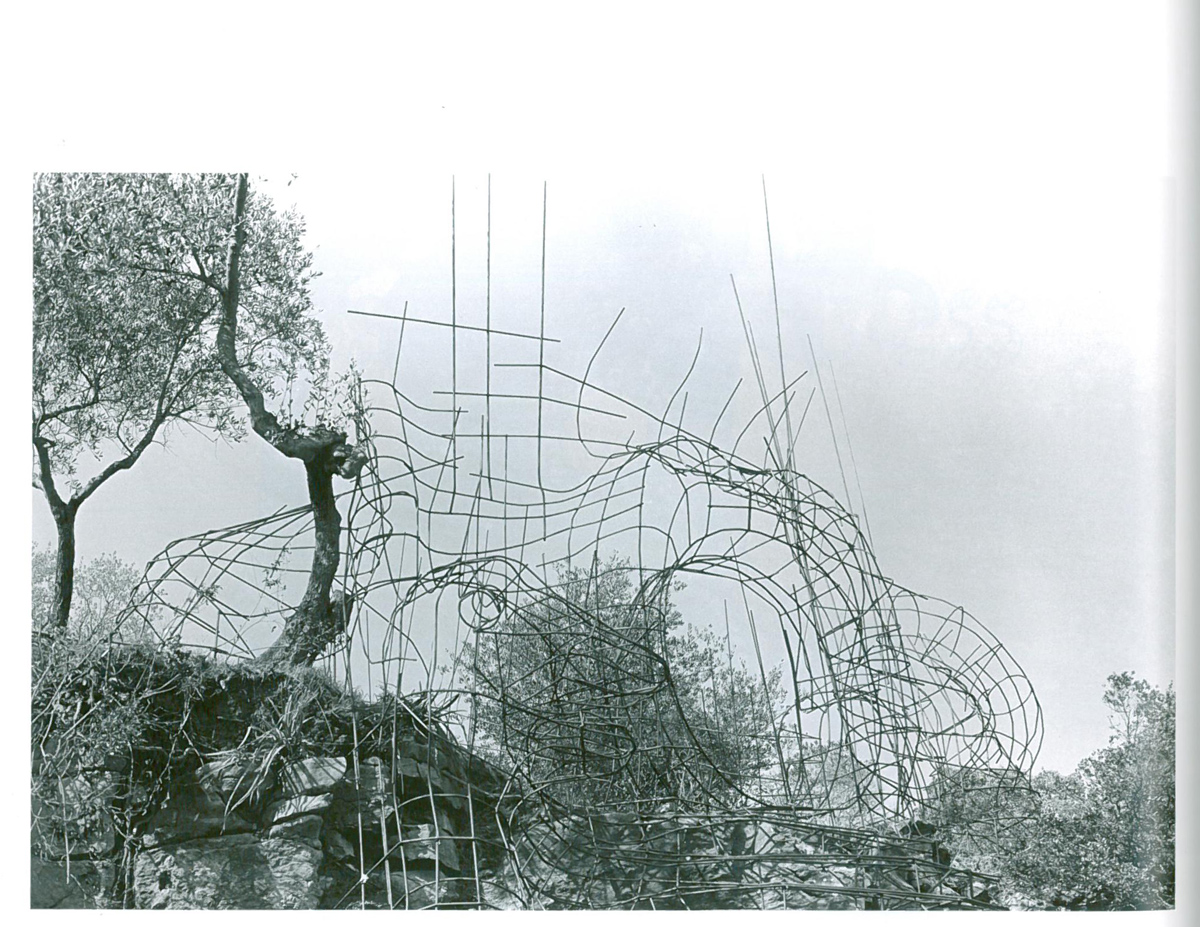

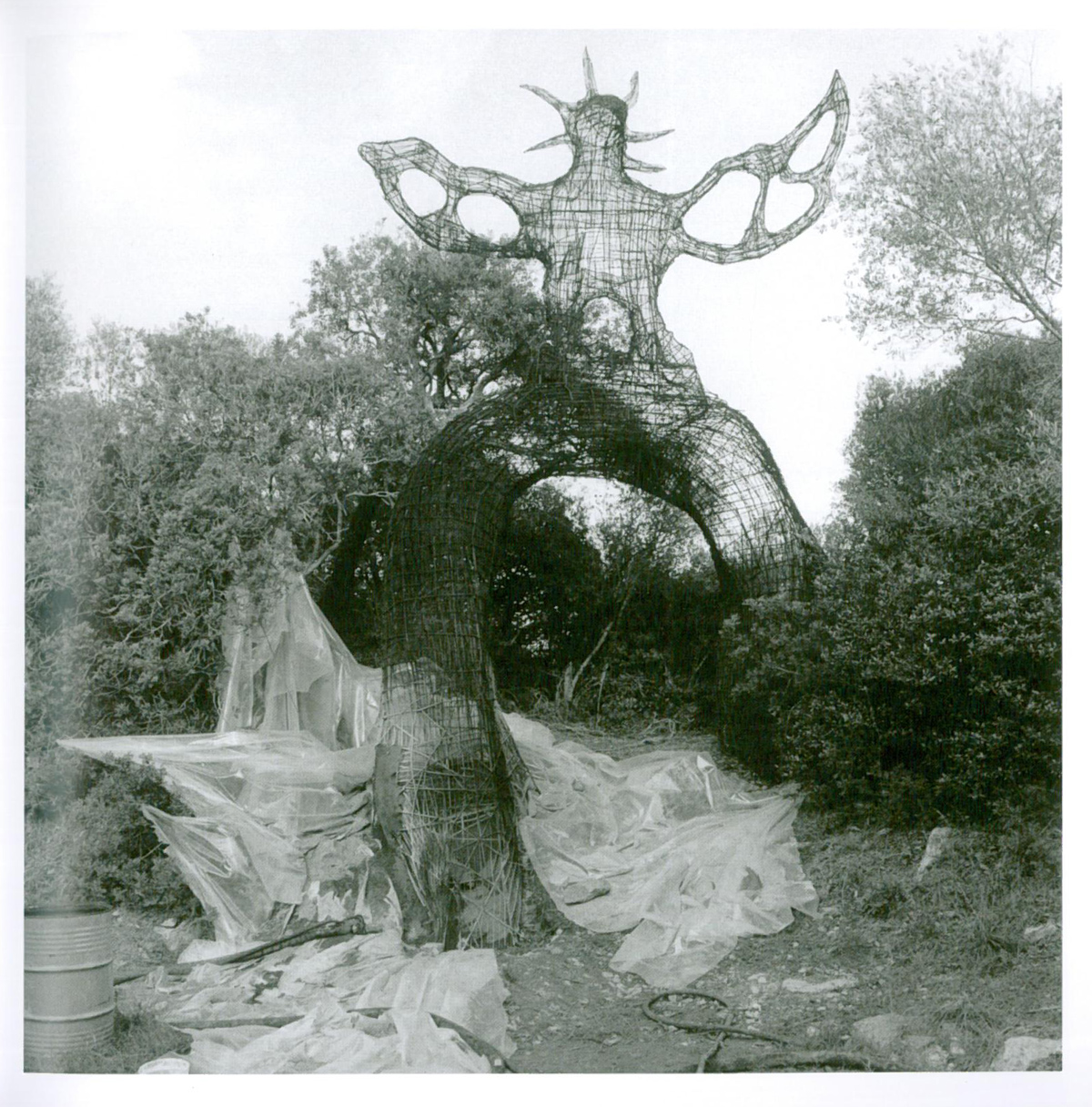

The High Priestess, in 1979, in her earliest stages of construction, as rebar begins to be welded.

Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi .

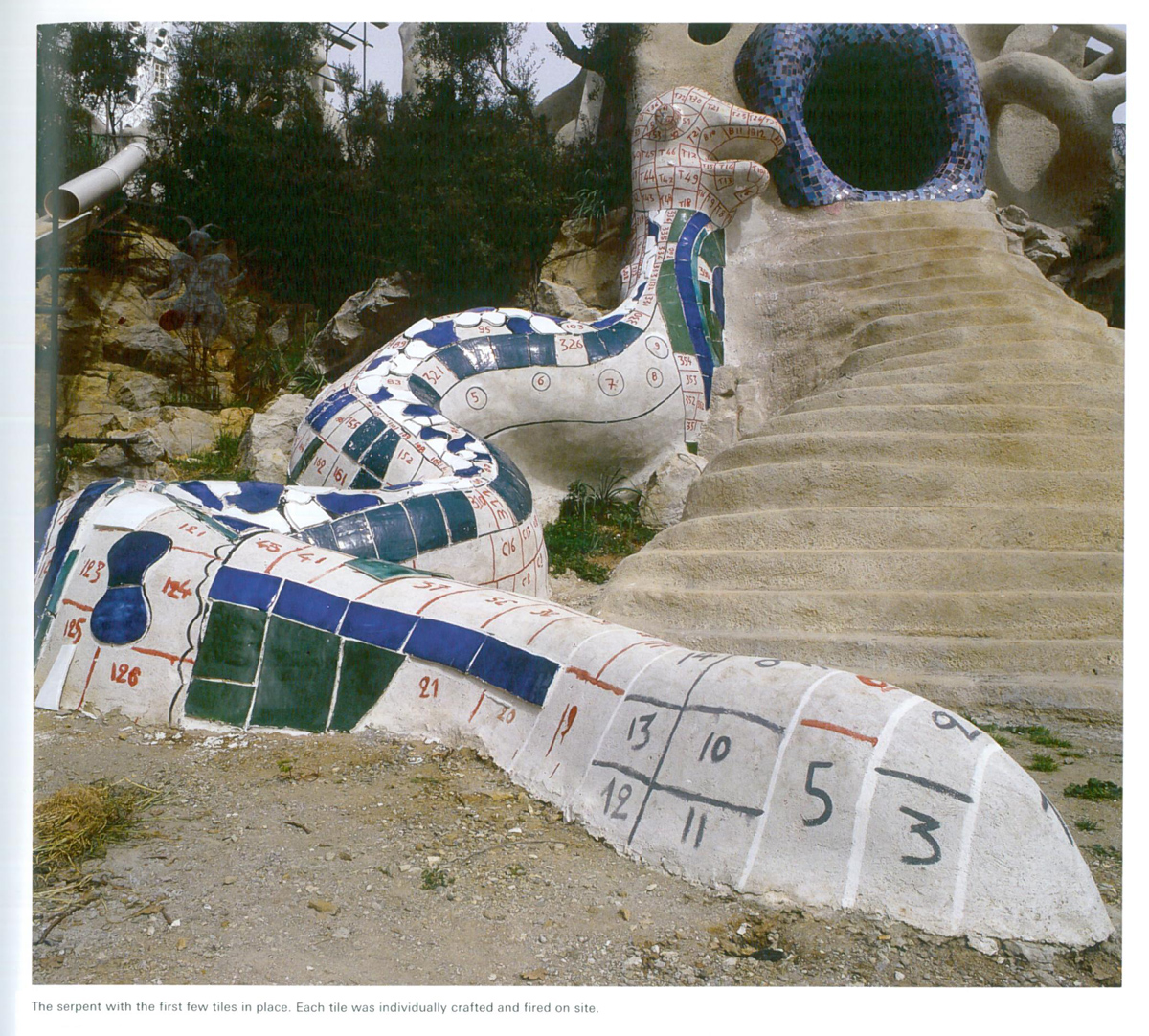

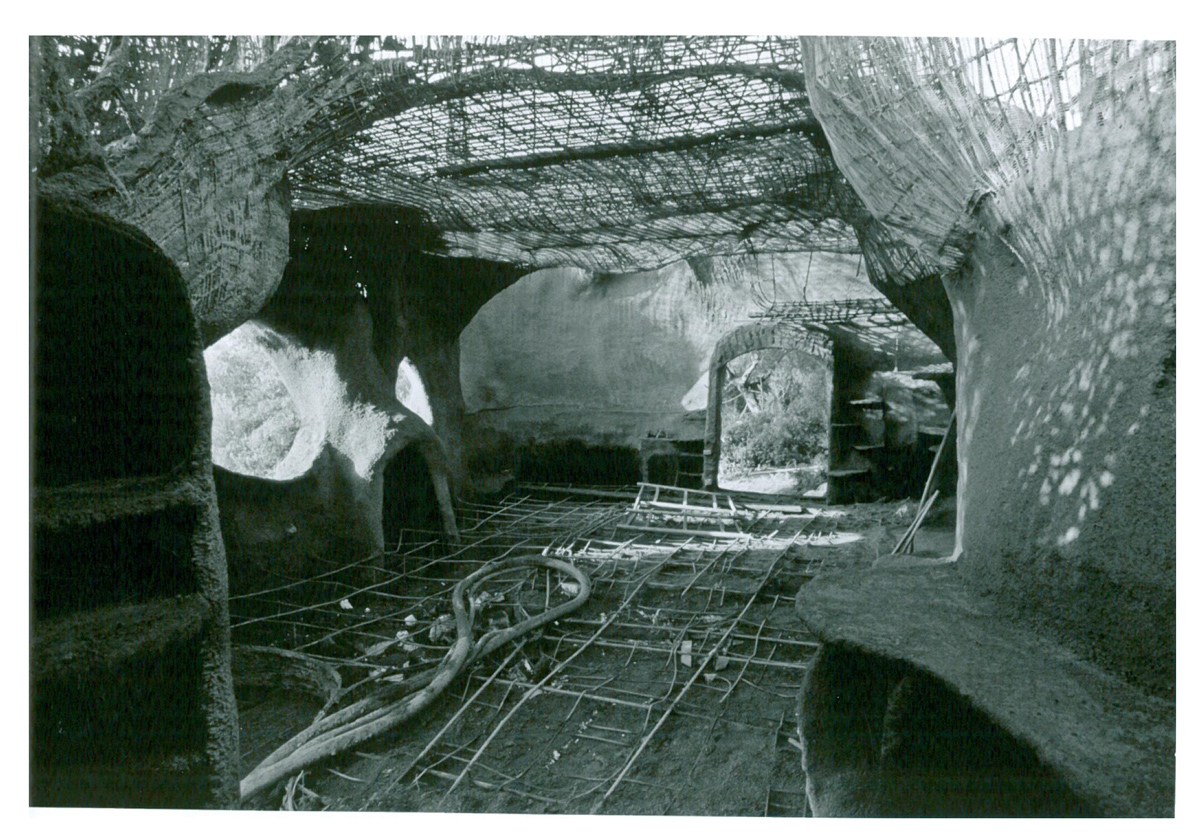

All of the large structures at the Tarot Garden were built upon frames of welded rebar… shaped by hand, in-situ. Once the metal forms were finished, they were covered with wire mesh. After that, gunite cement was sprayed over them. Later, the rough cement was smoothed with another layer of cement, this second layer hand-applied. The surface finishes of each piece varied: some were hand-painted by Niki. Others were entirely covered with hand-made tiles, or with mosaics. For each of the Tarot Garden’s sculptures Niki de Saint Phalle first made many scale models. Once a maquette satisfied her, on-site craftsmen would build a full-size metal frame which in every detail duplicated Niki’s small model. These transformations of Niki’s art into their full-and-finished-sizes were done entirely by eye…amazing! We’re not talking computer aided design…or even blueprints! As mentioned, Jean Tinguely was responsible for welding half of the structures; eventually he trained many local men to become welders.

In Niki’s guide to her garden, she gives details about materials, techniques and collaborators:

“The enlargement of my models was made perfectly with a medieval eye, by Jean Tinguely and Doc Winsen. All of the monumental sculptures’ armatures were made from welded steel bars, formed by brute strength on the knees of the crew. The first crew who welded in the garden were: Jean Tinguely, Rico Weber, and Seppi Imhof. They built The Sphinx [Empress], The High Priestess and The Magician. The Pope [Hierophant] was started by Doc Winsen and finished by Jean Tinguely; it was Jean’s favorite sculpture of all the garden.”

“The second half of the Tarot Garden — The Emperor’s Castle, The Sun, The Dragon [Strength], and the Tree of Life [Hanged Man] were welded by Doc Winsen, a Dutch artist. Doc was assisted by Tonino Urtis.”

The High Priestess, with The Magician atop her, under construction, in 1982. All rebar has now been placed, and cement will soon cover the entire structure. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

Niki on site, as High Priestess, and Tree of Life

are being built. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

Another view of the High Priestess, under construction in 1984. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

Detail of Serpent by the waterfall of the High Priestess, under construction. The first tiles have been affixed. Each tile was individually crafted and fired on site. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

We’re looking at the back of the High Priestess. Her pigtail of blue-tiled hair supports a stairway which leads up to the Magician.

I nearly missed seeing this, but Anacleto beckoned and pointed me toward this starry grotto, inside of the High Priestess. The pool feeds the waterfall that issues

from the mouth of the High Priestess.

![The Wheel of Fortune, Card X of the Tarot. Per Niki: “An age old symbol for the wheel of life. What goes up must come down. One day walking in the garden: Eureka! I had the idea of asking Jean Tinguely to make the wheel…into a fountain [with] the water flowing from the High Priestess.”](https://nanquick.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/wheeloffortune.png?w=177)

The Wheel of Fortune, Card X of the Tarot.

Per Niki: “An age old symbol for the wheel of life. What goes up must come down. One day walking in the garden: Eureka! I had the idea of asking Jean Tinguely to make the wheel…into a fountain [with] the water flowing from the High Priestess.”

Jean Tinguely’s sketch, dated 1986, for his Wheel of Fortune fountain. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

The Wheel of Fortune fountain. To the left of the pool, Vannella and Anacleto (neither of whom had visited the Tarot Garden before that day….see, I like to keep the lives of my Guides EXCITING) are conferring. Behind them is the long, dusty path that leads downhill, back to the Entrance Gate. In the far distance: farmland, and then the Tyrrhenian Sea.

Strength, Card XI in Niki’s Garden (although, in the Tarot, this card is # eight). Per Niki: “A frail maiden leads a ferocious dragon by an invisible thread. The monster the maiden must tame is herself. It is her own inner demons she must conquer. Through this difficult task she will discover her own strength.”

Strength — detail of Dragon’s Tail. See how perfectly the sculpture rests upon the natural rock of the site.

The Moon, Card XVIII of the Tarot. Per Niki: “The Moon is the card of creative imagination and negative illusion. The Moon is an interior card—mysterious, enigmatic. The Moon affects the tides, the menstruation of women, childbirth, and all things connected to the flow of water. The card of the Moon can be perilous or offer great imaginative power.”

Niki, in 1986, at work at her home/studio, which was inside of The Empress. Here, she’s completed a maquette of The Moon. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

Temperance, Card XIV of the Tarot. Per Niki:

“I had great difficulty understanding this card. It was too far from my passionate nature. Temperance seemed to me to be a compromise. A middle road. One day a light dawned. Temperance is the Right Way. I made an angel of this card which crowns the Chapel.”

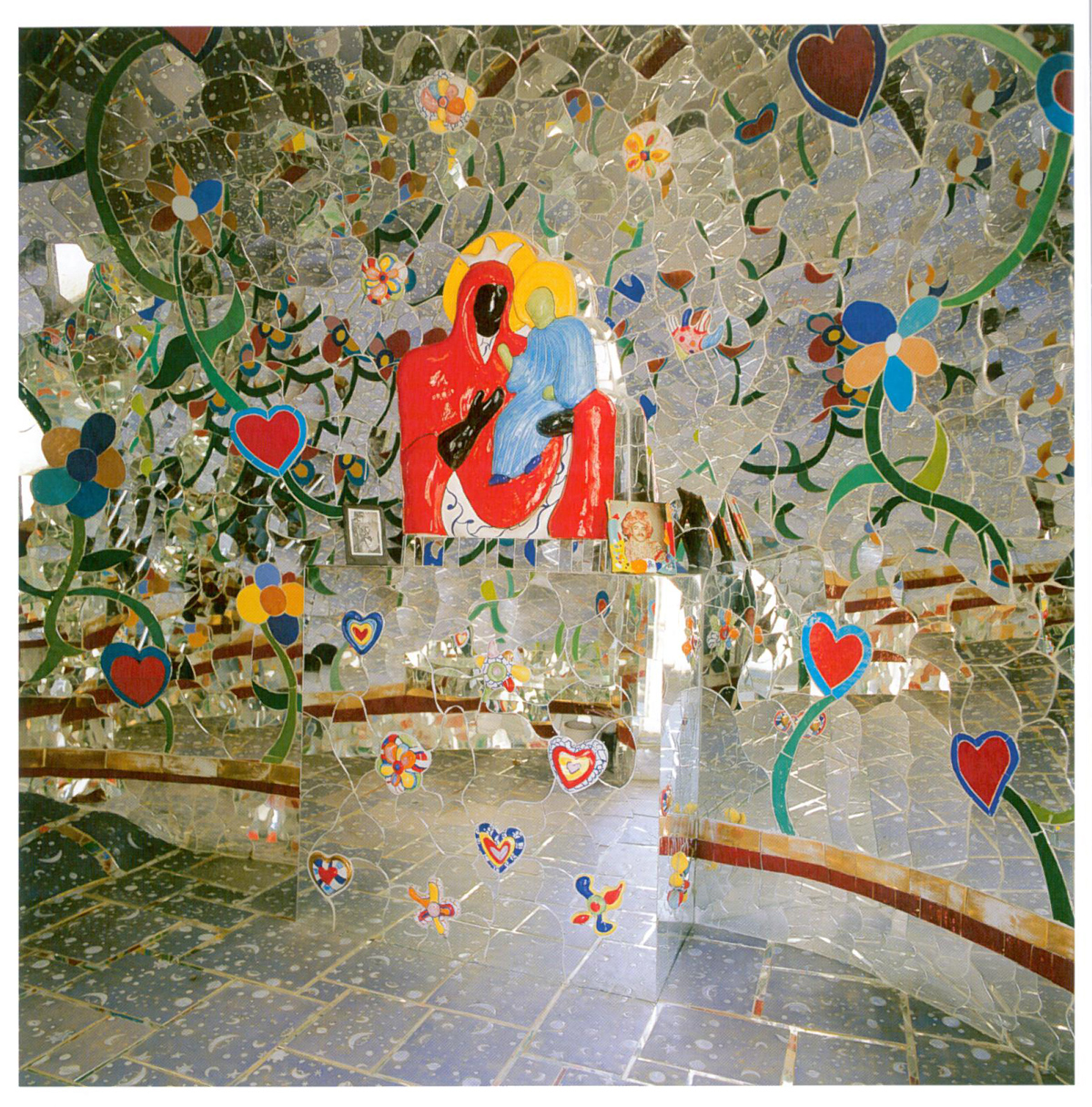

The Empress, Card III of the Tarot. Per Niki: “The Great Goddess. Queen of the Sky. Mother. Whore. Emotion. Sacred Magic & Civilization. In the form of a Sphinx. I lived for years inside this protective Mother. She also served for headquarters for my meetings with the crew. It was here we all had coffee breaks. On all she exerted a Fatal Attraction.”

The Empress, as seen from the top of the Magician.

Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

We’re walking along the South side of The Empress. Just above her head you can see a smidgen of the “broken” top of the Tower, with its metal sculpture.

Inside main living area of The Empress. In this photo, the double doors, along with the windows, are closed.

Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

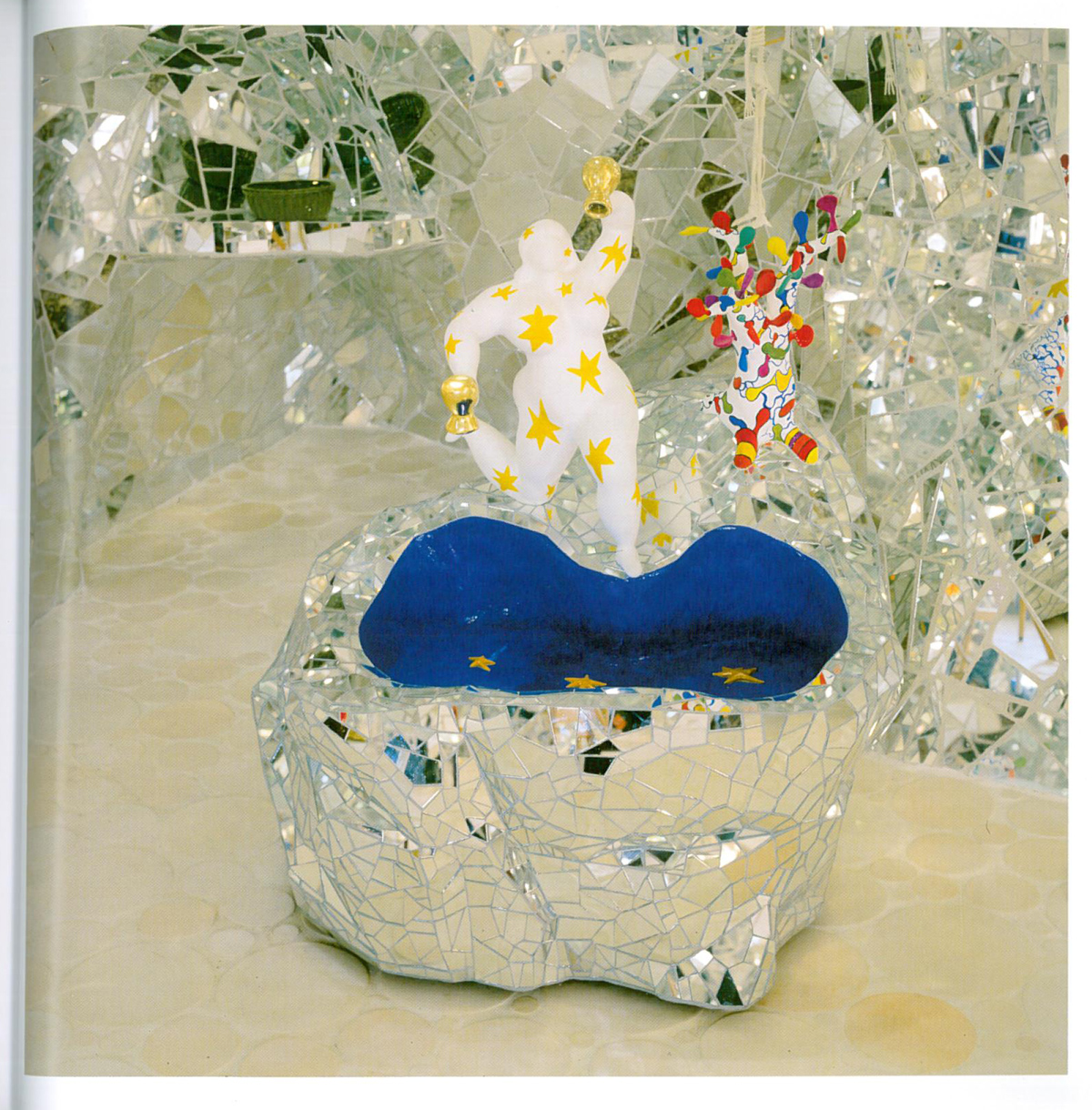

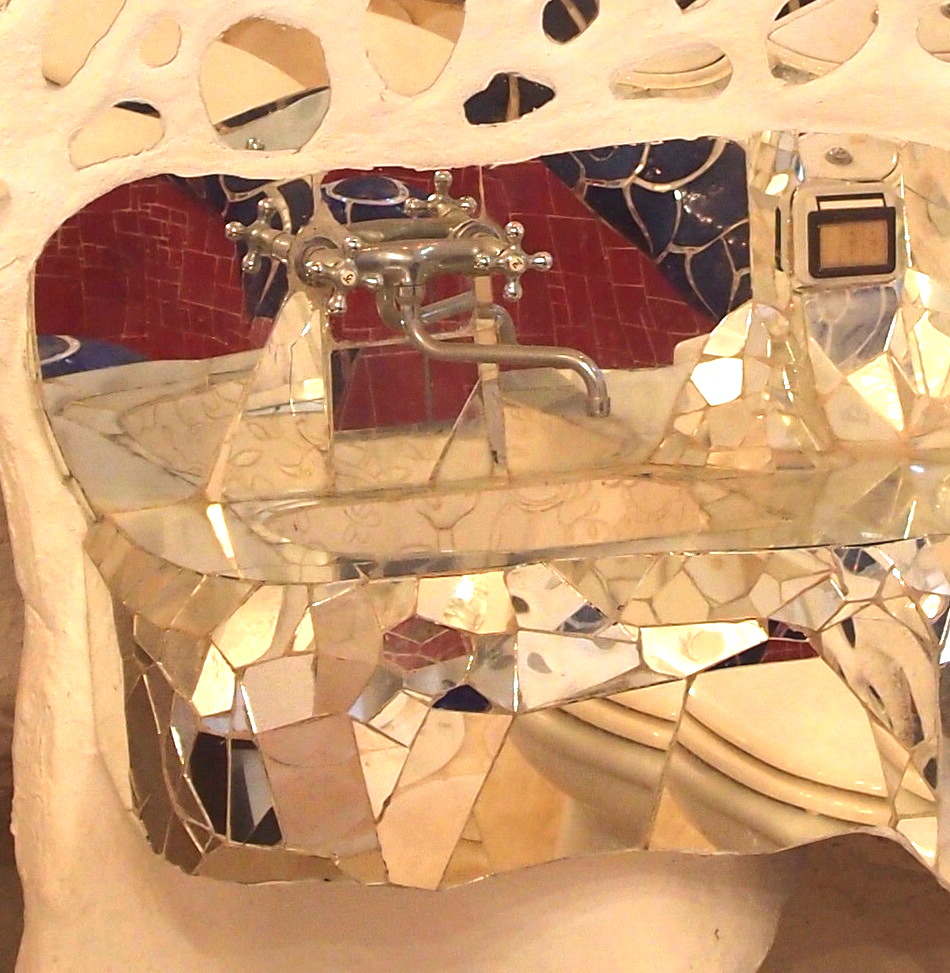

The interior of The Empress is covered, mosaic style, with thousands of randomly shaped scraps of mirror. In 1979, Ugo Celletti, the Postman in Capalbio, began to spend more and more of his time working at odd jobs in the Garden (which resulted in mysterious delays in mail being delivered to the town’s residents). In due course, Ugo became expert at mosaic work. It took him a full year to glue mirror shards onto all of the interiors of The Empress.

The main living area of The Empress, in 1983. The first layer of cement had just been applied.

Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

Anacleto and Vannella, in the main living area of The Empress.The chairs around the table were made by French artist Pierre Marie Lejeune, who began working at the Garden in 1980.

Niki’s Bedroom is on an upper level, inside of The Empress. We’ve got a view downstairs, into the main living area.

Back upstairs, in the main living area of The Empress we see two of Niki’s maquettes: for The Star, and for the Tree of Life.

Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

We exited The Empress, and walked along her North side (in the background we see an entrance to The Emperor).

On the North side of The Empress, hidden within the long strands of her Blue Hair, is a stairway, which leads to a roof terrace.

Atop The Empress: a porch and roof terrace…. and SPECTACULAR long views, across farmland and olive orchards, and, further west, to the Tyrrhenian Sea.

The Moon, as seen from the Roof Terrace of The Empress. Really….at this point I was ready for a semi-permanent stay in the Tarot Garden and thought about pitching a tent on the Roof Terrace.

And while I was having palpitations of JOY at the beauty of it ALL, a fellow Visitor sat nearby, oblivious to the charms of the Tarot Garden. Go figure.

Another view, from the Roof Terrace of The Empress.

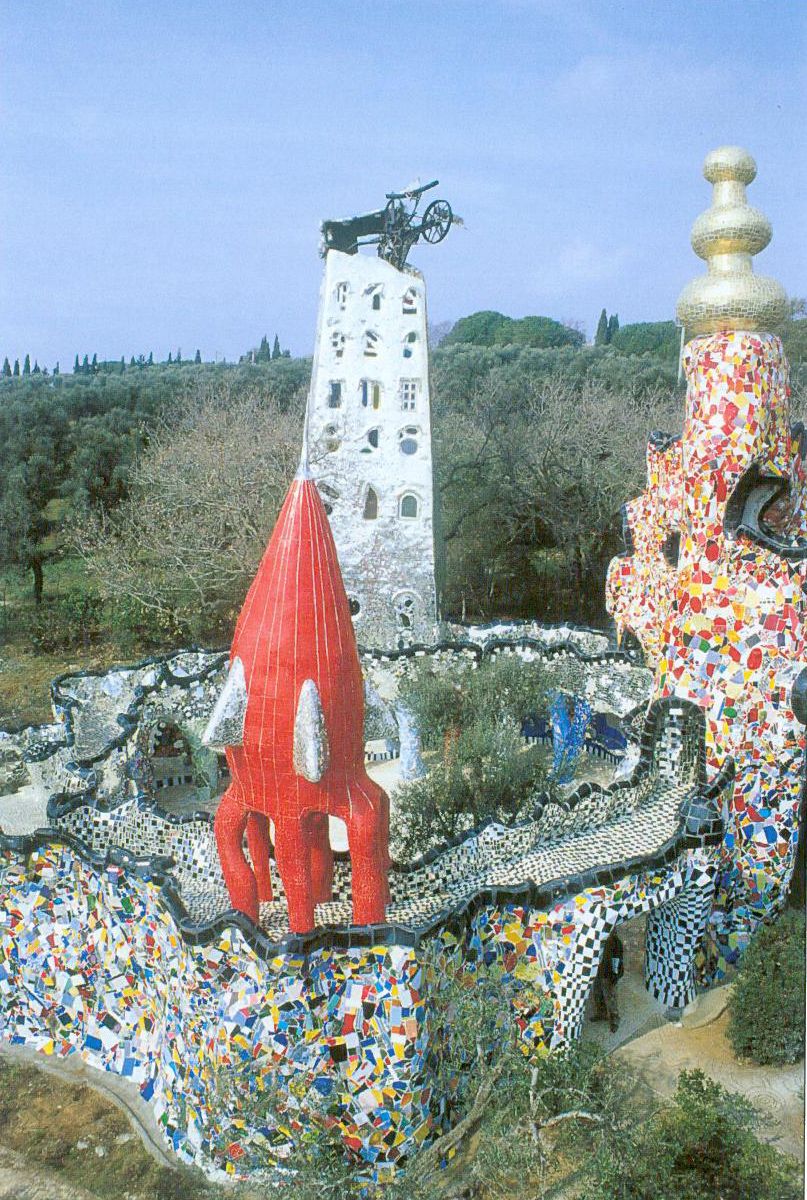

From the left: Mosaic-covered Spire of The Emperor; Red Rocket of The Emperor; The back of The High Priestess, with the Magician’s Silver Hand above her.

Yet another view from the Roof Terrace of The Empress. From the left:

The Tower (aka The Falling Tower); Spire of The Emperor, Rocket Ship of The Emperor.

Before I visited the nearby Emperor, I ducked back inside The Empress, where small pieces of sculpture in the main living area represent two more cards of the Tarot’s Major Arcana:

The Chariot, Card VII of the Tarot. Per Niki: “The Chariot represents Victory. It is the card of triumph over adversaries, over problems. In the card lies an inherent danger. At the moment of triumph, one must be most vigilant because one is most fragile.”

Judgement, Card XX of the Tarot. Per Niki: “In this card three figures rise from a tomb. That of the child, the middle aged, and the old-aged. They represent the three parts of ourselves that must merge into one. The angel urges us not to judge others, but to unite ourselves, rise up and become one.”

Judgement is inside the main living area of The Empress. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

The Emperor, Card IV of the Tarot. Per Niki: “The Emperor is the card of masculine power, for good or for bad. The Emperor is the symbol of organization and aggression. He has brought us science and medicine but also weapons and war.

He represents the Patriarch or male protector. He also desires to control and conquer.”

The Emperor consists of a circular courtyard, with a 2nd level walkway. The walkway is punctuated by a rocket ship and a multi-colored spire.

To the rear is the Tower, which grows out of the structure of The Emperor. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

Niki de Saint Phalle and Jean Tinguely, by Emperor’s Rocket, during construction. Image courtesy of Il

Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

We’re entering the Emperor’s Courtyard. This is yet another of Niki’s sublime indoor/outdoor spaces.

And hiding in a nook, on The Emperor’s upper level walkway, I found the Best Little Girl Ever. She’d driven

down from France with her family, just to visit the Tarot Garden. If this Apparation hadn’t already had a Mother, I would have volunteered for the Job.

The best thing about being surrounded by shattered mirrors: you can never tell if you’re having a Bad Hair Day.

Back down now to The Emperor’s Courtyard. Upon this column are the names of all the artists and craftspeople who built

Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden.

The Tower, Card XVI of the Tarot. Per Niki: “Some call this card the Tower of Babel. It represents constructions of a physical nature, or of the mind which are not built solidly. The Falling Tower is not only negative in aspect, it provides a lesson. Complex mental fabrications should fall apart. Jean Tinguely made a symbolic sculpture of Lightning ripping the Tower apart.”

My view of the Tower, from the upper walkway of The Emperor. The iron sculpture was proposed by Jean Tinguely,

who then welded iron to represent a bolt of lightning, as it strikes and damages the Tower.

The Tower. Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi. The Tower is one of the two giant sculptures in the Garden that have sleeping accomodations (the other is The Empress). From 1983 until 1992, Venera Fioncchiaro, a ceramic specialist who came from Rome, lived in the Tower. While at the

Tarot Garden, Venera taught 3 young women how to hand-craft

the tiles which Niki had designed.

In Niki’s Visitors’ Guide, she explains how the Garden’s extraordinary ceramics came to be:

“Venera Fioncchiaro would become the ceramist of the garden. It was total immersion. She lived at the garden and responded to my asking her to do new things in ceramics that had not been done before. The magnificent work she produced speaks for itself. She had several assistants. Sometimes the whole crew would be up at the ovens working too.”

“The twentieth century was forgotten. We were working Egyptian style. The ceramics were molded, in most cases, right on the sculptures, numbered, taken off, carried to the ovens, cooked and glazed, and then put back into place on the sculptures. When ceramics are cooked there is a 10 percent loss in size, so the resulting empty spaces around the ceramics were filled in with hand cut pieces of glass.”

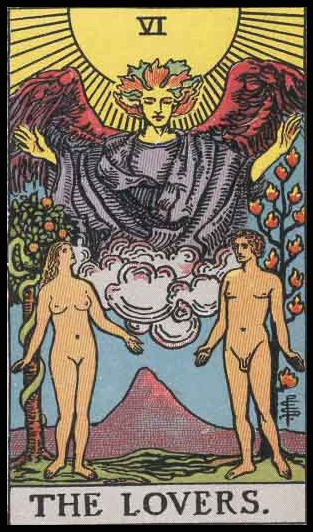

The Lovers (sometimes called The Choice), Card VI of the Tarot. Per Niki: “Adam and Eve were the first couple and made the first choice. The card implies there is a wrong and a right choice. A mistake can bring one closer to the truth of ourselves.”

Niki’s sculpture of The Lovers is one of many smaller works in the Garden. She wrote: “The smaller pieces in the garden were made by me in Paris, France with my assistant Marcello Zitelli. They were then fabricated in polyester by Robert Haligon and his sons, Gerard and Olivier. Temperance, Adam and Eve (The Lovers, or The Choice), The World, The Hermit, The Oracle, Death, and The Hanged Man were the pieces they fabricated. They were later covered in glass mosaic from Murano, Czechslovakia and France by

Pierre Marie Le Jeune and his wife Isabelle.”

Just beyond The Lovers, at the rear of the Tarot Garden are two striking sculptures which do not represent cards from the Major Arcana of the Tarot. These pieces are: The Oracle, and The Prophet.

We now return to our tour of the Tarot cards:

The Star, Card XVII of the Tarot. Per Niki: “The Star carries two jugs which spill water into stream-waters of Renewal.”

Justice, Card VIII in Niki’s Garden (although, in the Tarot, this card is # eleven). Per Niki: “Justice implies self-knowledge. One needs to acquire an ability to judge oneself, to come to terms with our dark side. With this insight one can judge other people and situations with a compassionate eye.”

Inside Justice, seen from the rear, is Jean Tinguely’s

motorized construction made in 1985, which represents “Injustice.” Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

The Hermit, Card IX of the Tarot. Per Niki: “The Hermit

is an experienced wanderer searching for a spiritual treasure. The card implies that the most important lessons are learned through the heart.”

The Hanged Man, Card XII of the Tarot. Niki placed the Hanged Man inside of her Tree of Life. Per Niki: “The Hanged Man has fascinated poets and artists throughout the ages. The Hanged Man is suspended by his foot. He is in the position to view the world upside down, thus in a new way. The card also

represents Compassion.”

Front limbs of the Tree of Life. To the left:

the blue hair of The High Priestess, with the Magician perching above her. In the background: the Emperor’s Spire, and the Tower.

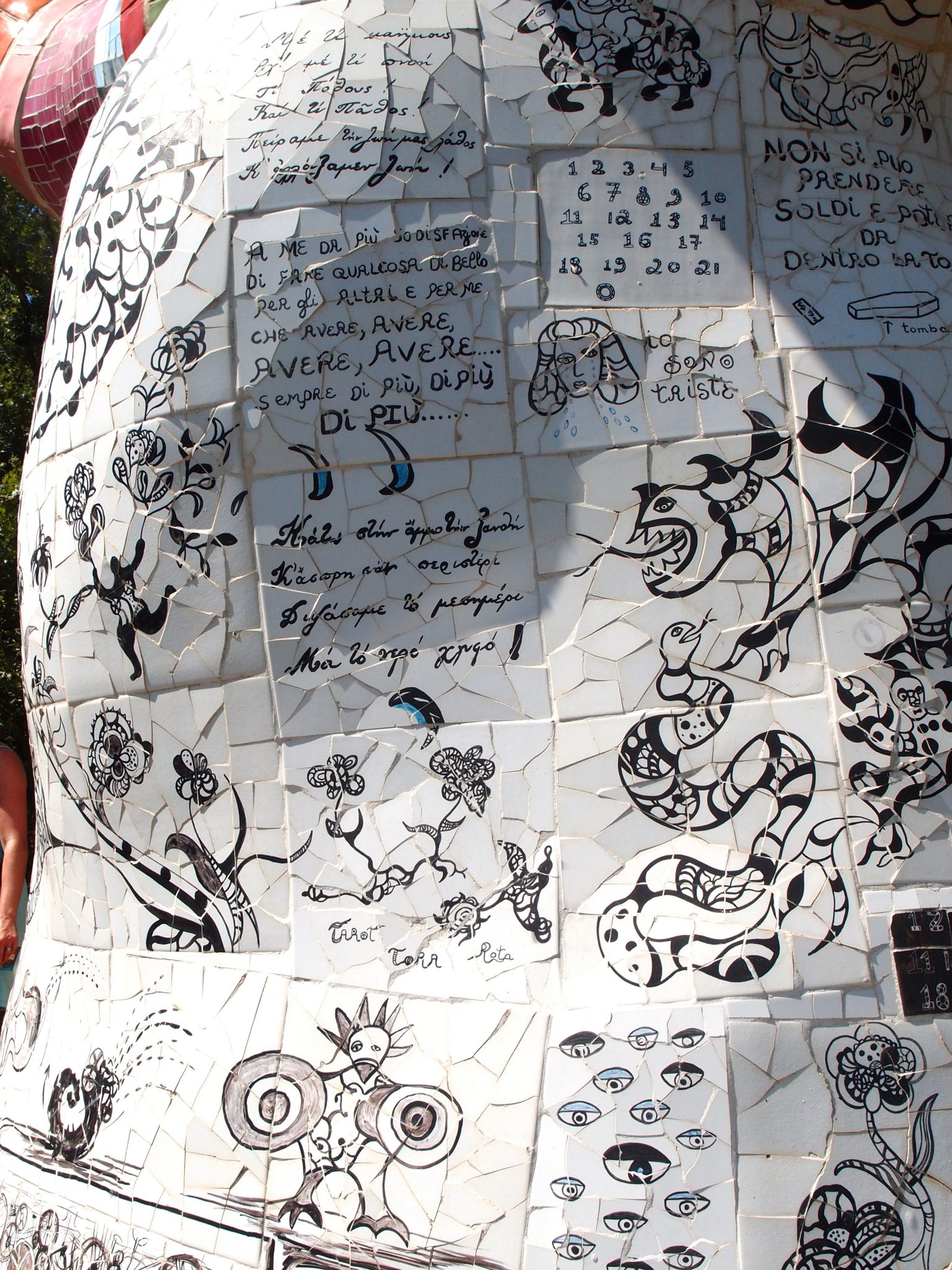

Detail of exterior of the Tree of Life. The tiles on the outside of this structure are densely covered with Niki’s scrawls. Translated, they’re a timeline of a love affair, which

ends in heartbreak. With drawings and these words, Niki begins: “I would like to give you everything, my mouth, my money, my imagination, my breast, my time, my terrific cooking, my everything.” Many tiles later, she writes “What shall I do now that you’ve left me? Will I cry a million tears? Will I die? Will I take to drink? Take a trip? Will I consult the stars and a crystal ball on how to win you back? Will we stay friends?”

Side view of Tree of Life, with Justice in the background, to the right, and the Tower, to the left.

The Hierophant, Card V of the Tarot. Per Niki: “Through this card one acquires knowledge of a sacred nature. He represents a teacher, a guru, a prophet, or a Pope.”

The Sun, Card XIX of the Tarot. Per Niki: “The Sun is a life force. I have conceived of the Sun as a Bird like those found in American Indian and Mexican legends. The bird is the creative closest to the Sun. “

Death, Card XIII of the Tarot. Per Niki: “Death. The great mystery. Without death, life would have no meaning. Death, the Great Reaper, allows new blossoms to grow. The card of death is a card of Renewal.”

The Devil, Card XV of the Tarot. Per Niki: “Card of Magnetism, Energy and Sex. The Devil also represents the loss of personal freedom through addiction of any kind. It scared me working on this card. I had visions of hundreds of devils swarming around the Sphinx, afraid they might attack me.”

The Fool, Card Zero, of the Tarot. Niki saw herself as The Fool in this Garden. She wrote: “The Fool in the tarot deck is as strong as all the other cards put together. Why? Because he represents man on his spiritual quest. No knowing where he is going, the Fool is ready to discover. He is the hero of the Fairy tales who appears dim witted but is able to find the treasure where others have failed. The Fool has few possessions. He travels light.”

The Fool (another of Niki’s “Skinnies”) is currently placed near The World, and The Devil, in the Tarot Garden. But because the Fool is a vagabond, his location will very likely change again…this is the ONLY alteration in the Tarot Garden that has been allowed, since Niki’s death.

The World, Card XXI of the Tarot. Per Niki: “The World is the card of the splendor of interior life. It is the last card of the Major Arcana. It is the answer to the Sphinx.”

Having gone full circle through the Tarot Garden, I knew that I had soon to ask my Guide and Driver to begin our long drive back to Rome (which, if the Gridlock Gods were feeling kind, would, at best, require two hours of late-afternoon road-time). But tearing myself away from the absurd charms of the Tarot Garden was proving to be difficult. I paused in front of the High Priestess, and realized that some other Visitors seemed to be sharing my reluctance about leaving. A little boy stood pensively at the edge of the Wheel of Fortune’s pool, his arms resting on its undulating wall. His mother pointed her camera, and sighed.

More than anything else that day, the responses of the many children who were also visiting spoke loudest about the true nature of Niki de Saint Phalle’s creation. When I’d first arrived, and had become aware of the numbers of families who were on site, I’d had a Grumpy Old Tourist Thought: “Oh God…there’ll be screaming kids, everywhere.” But, during my hours at the Tarot Garden, not a SINGLE child there had yelled, stampeded, or misbehaved in any way. Every young face had been turned upwards to marvel at the Garden’s Wonders; at Niki’s angels, and at her devils. Kids accept duality and the macabre, when we as adults cannot. Blissed out, and smiling, and with their hands eagerly stroking the inviting surfaces of Niki’s sculptures, the youngest visitors to the Tarot Garden all somehow understood that quiet, and reverence, were called for. And that calm radiated outwards. Parents of every nationality unfastened the reins on their little ones; permission was given for children to explore, on their own. The Garden seemed to be saying “You’re safe here. Discover, however you want to. Touch everything. Have a ball!”

Rather than being overstimulating, the Tarot Garden’s visual plenitude is soothing. Niki de Saint Phalle’s irresistible cornucopia of images, and colors and textures summon us all, to feast upon the fruits of her prodigious imagination. And by so doing, we are deeply nourished.

That day, I knew I’d only scratched the surface of things in Niki de Saint Phalle’s Tarot Garden. This is a place to which I shall certainly return.

Image courtesy of Il Fondazione Giardino Dei Tarocchi.

Copyright 2016. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this

material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

![Water pours out of the mouth of the High Priestess…]](https://nanquick.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/12/p7117946.jpg?w=768)

4 Responses to Two Modern Mannerist Homes & Gardens in Italy: Tomaso Buzzi’s LA SCARZUOLA, & Niki de Saint Phalle’s TAROT GARDEN