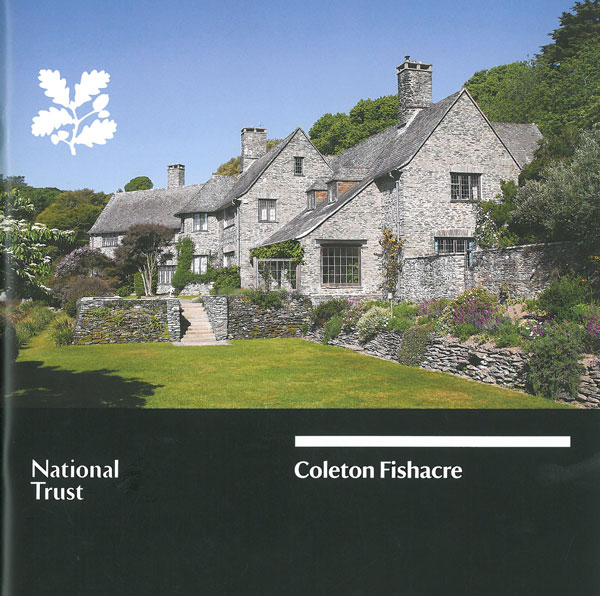

At Coleton Fishacre, by Pudcombe Cove, on the South Devon coast, we see a perfect, harmonious interplay of architecture and gardens and the greater landscape. The country retreat of Rupert and Lady Dorothy D’Oyly Carte began to be created in 1923. Rupert, the son of impresario Richard D’Oyly Carte, was the manager of the hugely popular—and profitable—Gilbert & Sullivan empire of operettas, as well as the owner of the Savoy Hotel and Claridge’s, in London. The Arts and Crafts-styled stone house and terraces were constructed largely from Dartmouth shale, which was quarried on site. On July 2nd, 2015, after a morning of dense fog and driving rain, the skies cleared, and Coleton Fishacre, which during the first hours of my visit had seemed to be a spooky Daphne-duMaurier-setting-made-real, was transformed into the glistening, cheer-inducing, jewel-by-the-sea that you see here, and which we will explore at length, in the final portion of this Travel Diary.

May 2016

Six months have elapsed since I published Part One about the summer-of-2015 week when my dear friends Anne and David Guy led me on a long ramble across Southern Devon. Of the varieties of jobs I perform, no work challenges me more, or gives me more satisfaction, than the creation of these Travel Diaries. With every article ( all of them composed after I’ve returned to my quiet New Hampshire life ) I try to replicate my virgin-views, and the excitement I felt, as I encountered each new place. Whenever I consider the backlog of material that I’ve already accumulated, I begin to frantically calculate just how many more decades I’ll need to stay alive, so as to finish the happy labors of this endless and self-assigned project.

Periodically, however, Life demands that the hours of every day be spent working through less happy challenges. Trouble always arrives in clusters. Over a short period of time, my mother, and three of my friends, abruptly die. And then the old joke about Death and Taxes is revived, as one of the worst jokes, ever. Deep sorrows or serious illnesses, finding the times ripe for their pernicious influences, sidle in and drape their various veils over those who remain.( And, My Oh My: I cannot even begin to bewail the cesspit that America’s political process has become!)

And yet….and YET: When I’m hip-deep in one of these extended periods of gritting teeth and summoning strength and practicing patience, I eventually realize that, so long as one remains calm and lucid, enduring awful times can result in the arrival of some of Life’s most unexpected gifts.

To wit: Ten years ago, I sat by my father’s bedside, as he suffered through the final stages of Lupus. This was a man who during his 80 years had lived largely for and in the future; always beside him were spreadsheets about the businesses he’d build, and piles of handwritten notes about the organizations he’d grow. But, in his final weeks, my father stopped looking ahead and instead turned his eyes to his immediate surroundings.

On an early morning in April I arrived at his hospital room with a freshly-baked baguette and a carafe of coffee. I spread butter on the still-warm bread, and gave it to him. I poured us each a cup of strong coffee, topped off with cream. For two months, as he’d been shuttled from one hospital to another, good bread and organic butter, and rich coffee and cream — along with all other tasty foodstuffs — had been denied him. But it was clear to both of us that his doctors, despite their frantic efforts on his behalf, could not stop his dying, and so I decided to end my father’s dietary deprivations.

As I did each morning, I read aloud to him, from the NYTimes Opinion Page. Normally, he’d offer a few words about the sorry state of the World. But on that Spring day in 2006, as I paused between editorials, my father, with coffee cup in one hand and buttered bread in the other, gave me the most open smile I’d ever seen and told me: “Nan, we have everything we need.”

Berkeley, California, 1953. Nan and her parents, Hazel and Elwyn, outside of their home at 2434 Byron Avenue. Egad…such geeky-looking parents, and such a serious-faced infant! Fortunately, as my parents aged, they both became much more distinguished-looking…and I developed a sense of humor. When we lived in this inexpensive, one-bedroom cottage near San Francisco Bay, my parents had to shoehorn my crib into a closet…shades of Harry Potter, who first lived in the under-stairs cupboard at the Dursleys’. Today, per Zillow, this only-slightly-expanded cottage is valued at $914,000.00 … utter craziness. Photo courtesy of Emily Hook

Now, having been shepherded through this recent, rocky stretch by my superb sister, by my small mob of beloved friends, and by a very smart doctor [Note: If you’re seriously ill, haul yourself off to Massachusetts General Hospital, in Boston…don’t waste time going anyplace else.] , my brain-fog has lifted and I am once again finding the energy to savor the bounties of Life, and to think about my past and future travels.

( Yes: another long journey is on my 2016 calendar. )

As the World seems always to be on the verge of going to Hell in a Hand-basket (one of my mother’s favorite laments), focusing upon the positive — upon all the ways in which we humans have improved ourselves and embellished our Little Rock — seems the best way to counteract our host of other, un-admirable tendencies, which, these days, are on full and distressing display, across the globe.

And so, the most constructive thing I can do today is to resume my journal about more of the extraordinary places to which Anne and David led me last summer, in Southern Devon.

Tuesday. June 30, 2015.

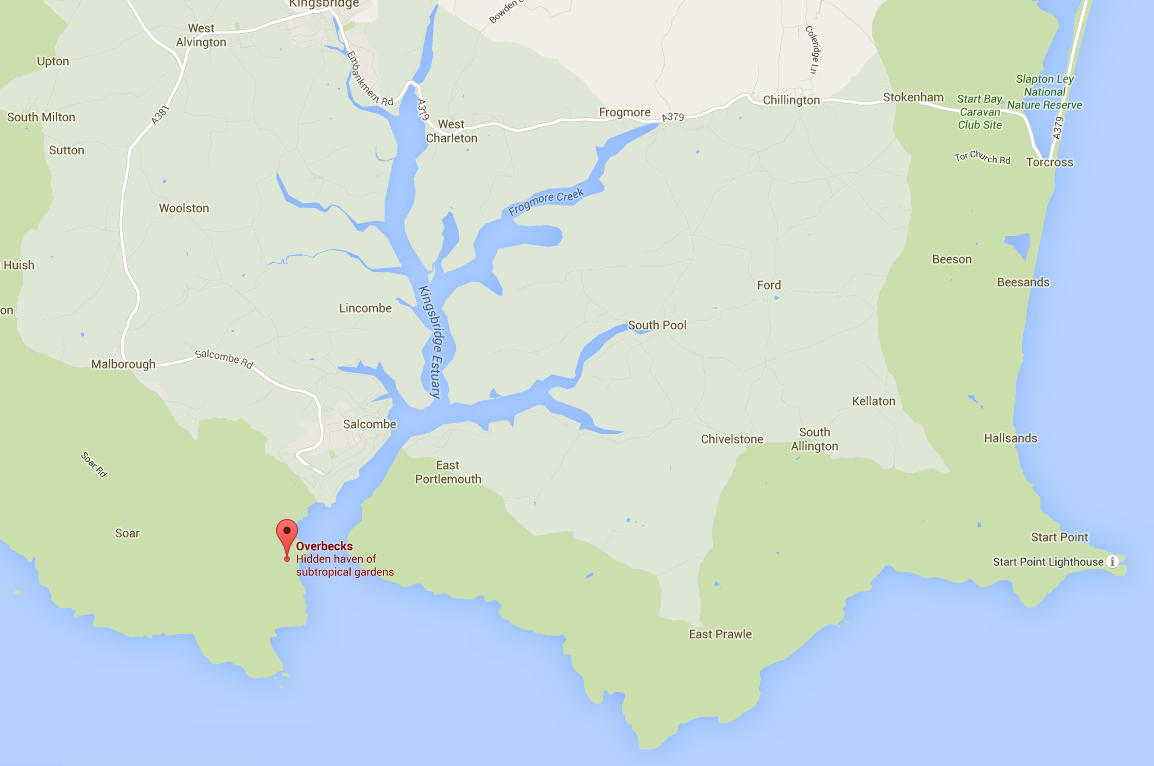

Our destination: Overbeck’s

Sharpitor, Salcombe

Devon, England TQ8 8LW

Phone +441548842893

Website https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/overbecks

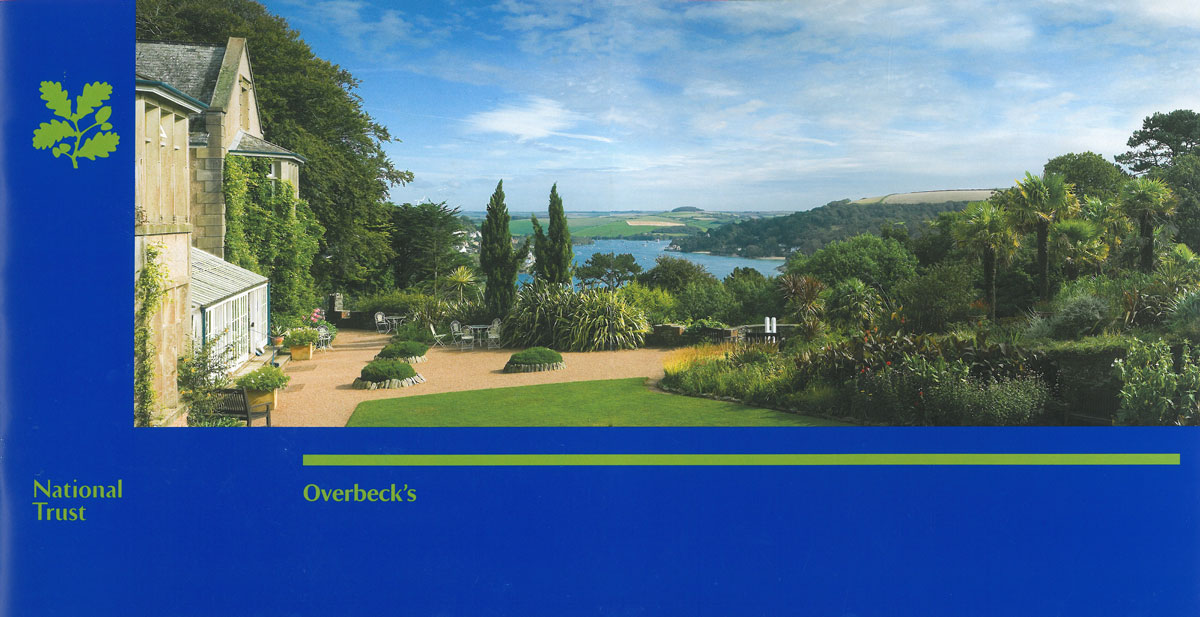

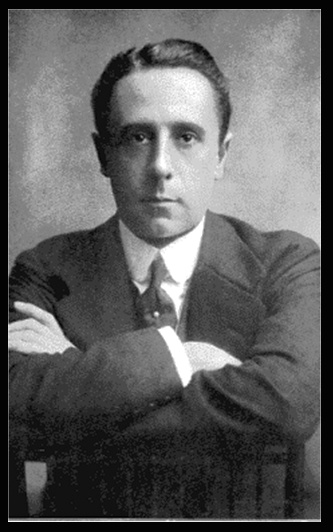

Otto Overbeck bought his house, originally called Sharpitor, in 1928. Upon his death in 1937, the house and garden were bequeathed to the National Trust, with the stipulation that it should be renamed Overbeck’s. Image courtesy of The National Trust.

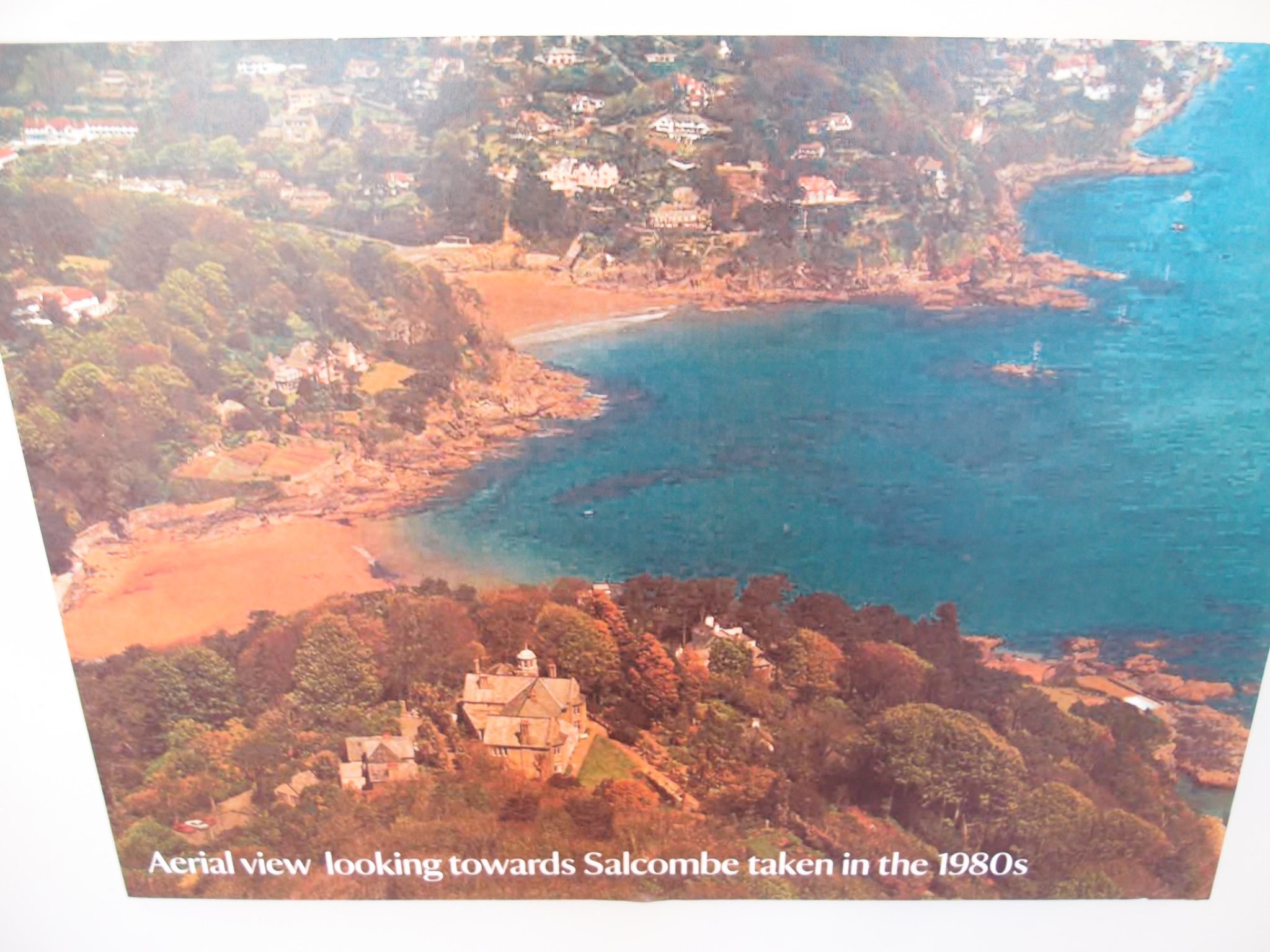

Aerial View of Overbeck’s. The road (if it can be called that) to Overbeck’s is winding and terrifyingly narrow…more a paved goat-path than a place for automobiles, however compact they may be. Unflappable as always, Anne Guy steered her vehicle upwards, with but a few sideways glances at the rock walls, and steep drops, alongside the steep approach to the House. Occasionally she played “chicken” with a car that was headed in the opposite direction: she nearly always won.

On display inside of the House: this aerial view of Overbeck’s.

The National Trust introduces Overbeck’s this way:

“A hidden paradise of subtropical gardens and quirky collections…

Welcome to the seaside home of inventor and scientist Otto Overbeck. His gardens and house are perched high on the cliffs above Salcombe, with glorious views over the estuary and coast. Walking through the garden is like taking a trip around the world. With palm trees, banana plants, citrus and olive trees, you could easily forget for a moment and expect to see a parrot flying up above.”

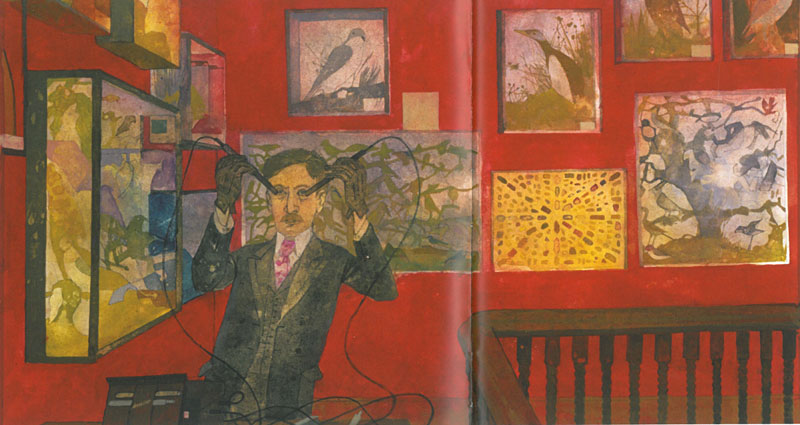

I’ve always maintained that creating a garden — especially one that is large and ambitious and which requires serious earth-moving at the outset — is an impractical and somewhat lunatic endeavor. It thus seems appropriate to introduce you to the first gardener in today’s Tour: Otto Christoph Joseph Gerhardt Ludwig Overbeck — in all of his Glorious Lunacy — as painted by Leonard Rosoman.

Artist Rosoman’s portrait of

Overbeck, as he demonstrates his Electrical Rejuventor upon himself. Image courtesy of the National Trust

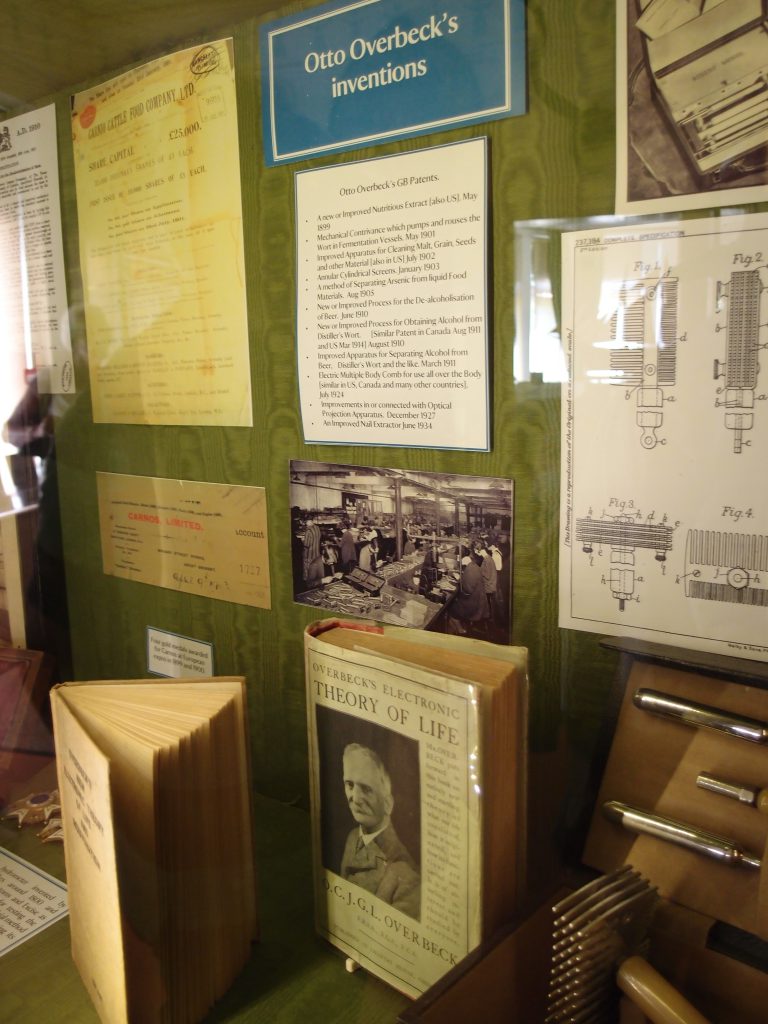

The National Trust’s description of Overbeck includes these nuggets:

“A research chemist by profession, he was also an accomplished linguist, artist and inventor. Otto also discovered that a waste product of brewing was in fact a nutritious food: he called it “Carnos” (Greek, for meat). A few years later the same method was employed to create the famous MARMITE.”

Marmite, in my Yankee’s-opinion, is the black, gooey, salty spread which the English use to ruin their morning toast….utterly revolting! When a Brit describes something as “a bit Marmite,” he’s talking about an acquired taste.

Proving that, in all eras, the dream of a fountain of youth springs eternal:

“Otto’s most successful invention was the ELECTRICAL REJUVENATOR that he patented in the 1920s, and which he claimed could defy the aging process if users applied the electrodes from his device to their skin.” Otto declared: “’Since completing my apparatus and using it on myself, I have practically renewed my youth. ‘ Overbeck successfully marketed the Rejuvenator, worldwide. He used to say that by means of his rejuvenation machine he intended to live till he was 126: he passed away when he was only 77.”

But, what matters today is that Overbeck’s inventions made him money; and those funds allowed him to add thousands of exotic and sub-tropical plants to the already-in-place terraces which Edric Hopkins, the first owner (from 1901 until 1913), had built on the rocky, cliffside site.

We enter Overbeck’s . Note the bright turquoise of the Salcombe estuary in the distance, and how

the wrought iron railings have been painted to match, in what is called Overbeck’s Signature Blue.

Among the many peculiarities of the Southern Devon coast are its pockets of Mediterranean micro-climates. Taking advantage of Salcombe’s mild winters and warm southern breezes, Overbeck was able to embellish his 2+ acre garden with a huge range of decidedly NON-native plants : 3000 palm trees were added, along with bananas, oranges, lemons and pomegranates.

Guided by his head gardener Ellis Manley, Otto nurtured plants which are native to tropical Asia, such as his camphor tree (Cinnamomum camphora), along with specimens from Africa, South America and New Zealand. When one remembers that Overbeck gardened here for a mere nine years before his death, his horticultural transformations of the property are even MORE stunning to behold.

We arrived at 9:30AM, a half hour before opening time. Early Birds can linger on this terrace, with its stunning view, down the Estuary.

This side of the House, seen from the entry area, is an anarchic combination of shapes and styles…which seem quite at home in Overbeck’s English Jungle Garden.

The National Trust’s gardeners who today tend Overbeck’s rely solely upon rainwater and runoff collected from roofs for irrigation. State of the art composting provides all of the necessary mulch and fertilizer for the garden, which, though compact, feels vast because the site offers spectacular and varied views of the estuary and ocean.

The plants at Overbeck’s, while exotic, are none of them sissies! Most survive without winter protection. And the free-draining soil, which is composed of millions of minute rock particles from the excavated cliff, ensures that root systems of the plants do not rot during England’s wet seasons. Whether by design or by chance, Otto Overbeck found the perfect place for his horticultural adventuring.

Before we began our tour of the gardens, we enjoyed coffee and cake (there’s ALWAYS time to eat cake…) on the Tea Room’s Terrace.

Inside the Tea Room proper, this painting by Leonard Rosoman, of Otto Overbeck in his garden, adorns the mantle.

The former billiard room is now the Tea Room, where a sign at the door cautions that wait-times for food will be LONG, due to each plate being prepared to order. Later, at lunchtime,

we discovered that the food was well-worth waiting for.

The House, originally named Sharpitor, was built in 1913 (to replace an earlier structure). Shortly thereafter, the new owners, Captain and Mrs. George Vereker, converted Sharpitor into a Red Cross convalescent home for soldiers, in tribute to their 21-year-old son, who had been killed, just 22 days after the start of World War I. By January of 1919, the Verekers had welcomed 1020 wounded soldiers to their home; I imagine that the warm sunshine there, along with the incredible generosity of the Verekers, healed a good many men.

Well-nourished, we headed across the Tea Room Terrace Lawn, towards the Upper Gardens.

The Gazebo Garden has a small, sheltered seating area. This hidden pocket of Overbeck’s is planted with cistus, and myrtle trees with cinnamon bark.

We’re back in the Rock Dell, where the incongruous combination of tall palms with blowzy hydrangeas is charming.

Anne, a professional garden designer, does some close inspection of the plantings in the Rock Dell. Some of Anne’s work can be seen at

www.anneguygardendesigns.co.uk

Downslope from the Olive Grove is the Statue Garden, which stands upon the former site of a tennis court. I realize that, among English gardens, some of the nicest I’ve seen are those which have replaced a tennis court (the most fabulous being the New Water Garden at Kiftsgate Court, in Gloucestershire, which I featured in my

Armchair Diary titled “An Idiosyncratic Survey of Sculpture in Gardens of the Western World.”).

The Statue Garden predates Otto Overbeck’s ownership of Sharpitor. The statue in question, a bronze figure of a girl whose fingers originally supported a bird, was somewhat modified during the Second World War. Whereas the occupants of the property during WWI were convalescing British soldiers (and were thus guests who weren’t terribly rambunctious), the American soldiers who were stationed at the house during WWII were a friskier and less well-behaved bunch. The bronze bird in the hand of the bronze girl was too tempting, and soon became a victim of the soldiers’ target practice. Seems we North Americans, when stationed abroad and with time to spare, sometimes go a bit nutty with our firearms (also see my photo of the pockmarks left by Canadian troops’ buckshot blasting at the garden walls at Lullingstone Castle’s World Garden, in Kent, in my article “Rambling Through the Gardens & Estates of Kent, England. Part One!”).

We enter the Statue Garden, which contains lush plantings of tender perennials: poppies, salvias, agapanthus, cannas, kniphofias, inulas and heleniums…all chosen as sources of food for the bees and butterflies who flock there, from early June through the end of Autumn.

The Secret Garden overlooks this Parterre, which was planted by the National Trust in 1991. The clipped box hedging is cut twice a year, by hand.

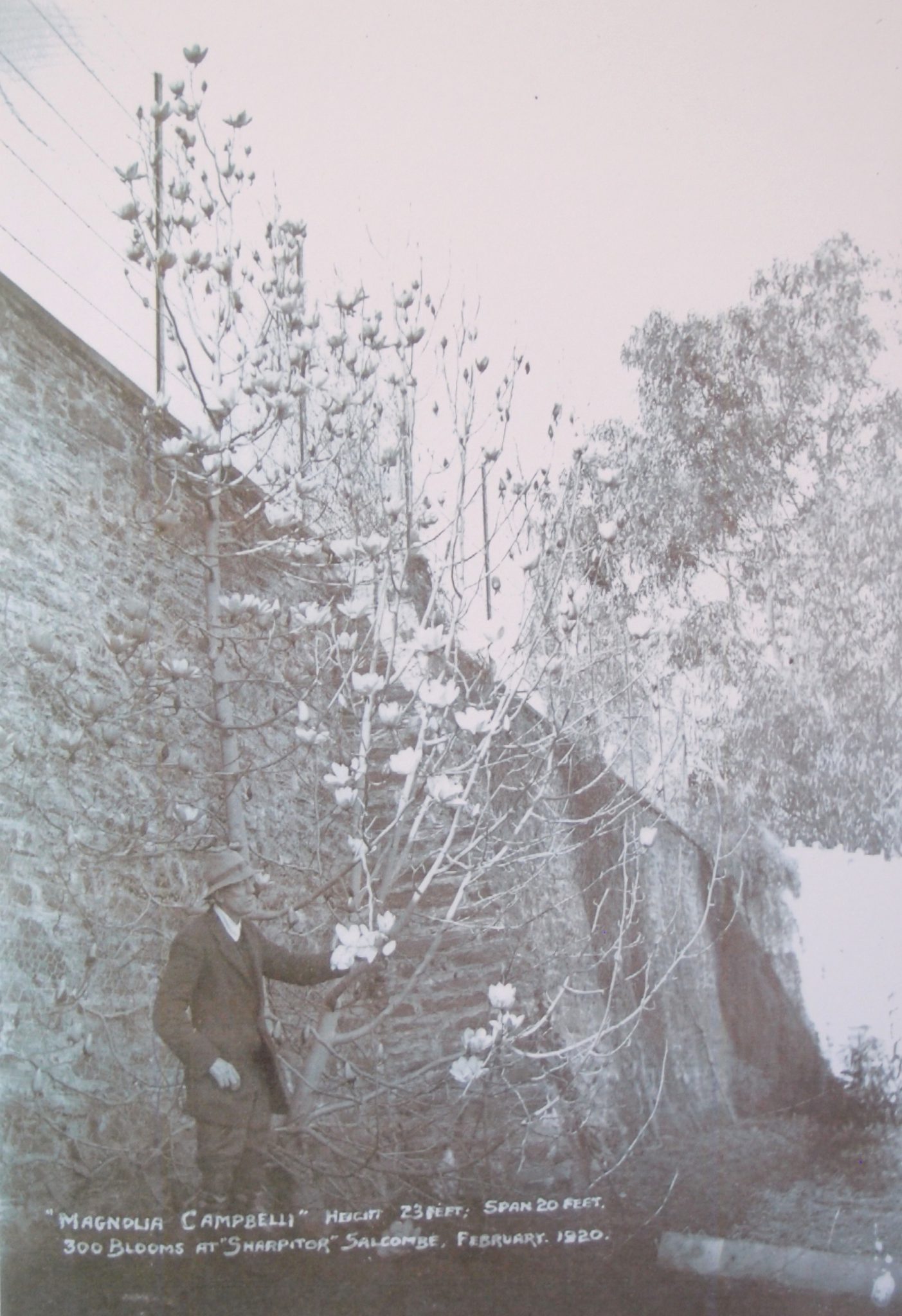

Below the retaining wall of the Statue Garden,

a Himilayan Magnolia campbelli grows along the

path leading to the Banana Garden. Planted in 1901, the magnolia tipped over in the Winter of 1999 during a heavy rain, but, despite its topsy-turvy situation, the tree continues to show healthy growth.

The Banana Garden is the most sheltered part of Overbeck’s. The bananas are one of the few plants in the gardens which need some added protection. Each Winter the stems are wrapped in fleece, and then covered with a mesh overcoat to keep some of the rain out.

Otto Overbeck planted his expansive Palm Gardens on a series of terraces which were built in 1901 by Edric Hopkins, the first owner of the property.

The Palm Gardens sprawl across steep, gravelled banks and terraces. All of the Chusan Palms date from the 1930s, during Otto Overbeck’s residency.

The Palms are complemented by plantings of Tree Echium, agaves, yuccas, ornamental grasses, and exotic flowering shrubs.

The Woodland provides coolness and shade and, more importantly, a bit of decompression after all of the visual stimulation of Overbeck’s exotic plantings. This tiny woodland area shelters the rest of the gardens from cold north winds, and is composed largely of naturally-occurring beech trees and evergreen oaks.

Until his End, Otto — chemist, collector, artist, inventor and plant maniac — operated at full throttle.

Needing a protein-boost? Spread a brewer’s waste product on your breakfast toast! Feeling Poorly? Hook yourself up to the Rejuvenator for some gentle, stimulating electrical currents (because, after all, most of mankind’s ailments are due to an imbalance of electricity). Having a crisis of faith? Listen to Overbeck, who maintains that the universal force of electricity makes religion obsolete… (Discuss! )

Clearly, there was never a dull moment with Otto … not inside of his brain … nor outside, in his garden.

Otto Overbeck didn’t just accumulate plants.

Inside the House a small selection of his collections is on display. In the Staircase Hall are samples from his encyclopedic natural history collection: stuffed animals and birds and fish, birds’ eggs, fossils, and butterflies.

Hidden under the stairs is a room that’s full of the dolls’ houses which belonged to the Overbeck family.

In Overbeck’s Maritime Room: a tribute to Salcombe’s 19th century glory days, when it was a busy seaport. The paintings and scale models on display here are a catalogue of maritime disaster: every ship shown was lost at sea.

Otto Overbeck spent the final decade of his highly unusual life creating a garden which is nothing short of sublime.

This was my parting-view of Overbeck’s, as Anne and David and I began to climb the stairs, back to the Main Gate. That such an Exit should be so seductive is almost perverse: leaving Overbeck’s that afternoon became very difficult for me.

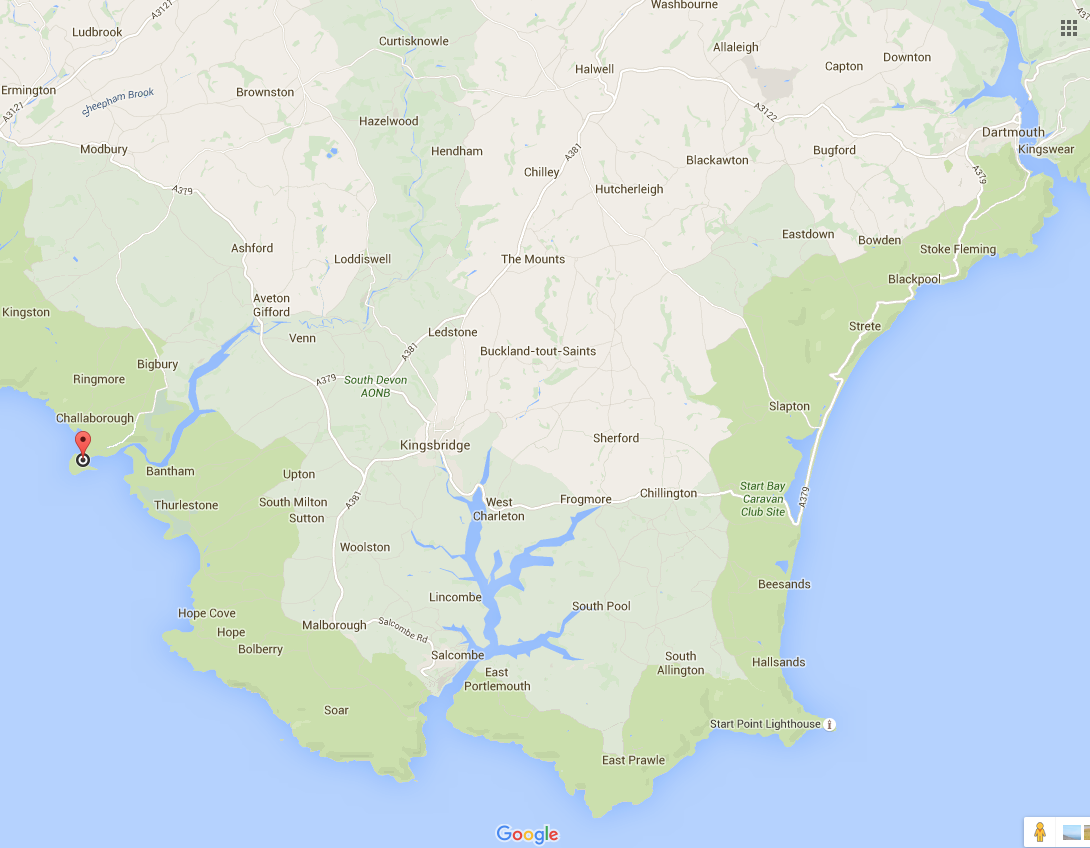

But, despite my foot-dragging, David and Anne declared “Onward!” ‘Twas time for a flying visit to the Beach at Bigbury Bay, and a view of Burgh Island.

Our Destination: Bigbury-on-Sea-Beach, on Bigbury Bay

Devon TQ7 4AZ

As I explained in Part One of my guide to Southern Devon, although she died in 1976, the presence of Dame Agatha Christie remains strongly felt, along the riverfronts and seacoasts of the area.

Agatha Christie loved Southern Devon: she was born in 1890, in Torquay, and for the last two decades of her life she made her country home at Greenway, on the River Dart.

Agatha cranked out 66 mystery novels, as well as collections of short stories, and a play: THE MOUSETRAP is the world’s most continuously-produced drama, with more than 25,000 performances notched up. For Christie-fans, there are various Christie-themed tours of her old stomping grounds in Devon, as well as the biennial International Agatha Christie Festival, which is held in Torquay. Having already taken me to Christie’s home at Greenway (see Part One of my Devon Diary), Anne and David thought I should also see the place in Devon which inspired her most famous mystery story.

I was 12 years old when I first encountered Christie’s novel, AND THEN THERE WERE NONE.

I had the bad judgment to be reading it on a hot summer’s evening, while I was babysitting, in a large, strange house.

I recall vividly how frightened I became, as Christie, with relentless precision, spun her tale of methodical, multiple murders.

Ten people are lured to an island — an island inspired by

Burgh Island, and which Christie renamed “Soldier Island.” Each guest finds the following ditty posted in his or her room:

“Ten little Indian Boys went out to dine;

One choked his little self and then there were nine.

Nine little Indian Boys sat up very late;

One overslept himself and then there were eight.

Eight little Indian Boys traveling in Devon;

One said he’d stay there and then there were seven.

Seven Little Indian Boys chopping up sticks;

One chopped himself in halves and then there were six.

Six Little Indian Boys playing with a hive;

A bumblebee stung one and then there were five.

Five Little Indian Boys going in for law;

One got in Chancery and then were four

Four Little Indian Boys going out to sea;

A red herring swallowed one and then there were three.

Three Little Indian Boys walking in the zoo;

A big bear hugged one and then there were two.

Two Little Indian Boys sitting in the sun;

One got frizzled up and there was one.

One Little Indian Boy left all alone;

He went out and hanged himself and there were none.”

Christie’s rhyme is predictive: by story’s end, None remain on her Island (but of course there’s a Final Twist….).

I have long since outgrown Agatha’s formulaic stories; lately I’ve been enjoying these better written and more subtle British mysteries: Christopher Fowler’s Bryant & May novels, and Ben Aaronovitch’s Peter Grant adventures. But I suspect that, even now, in my dotage, a re-read of AND THEN THERE WERE NONE would still give me the willies…and I would have quite a bit of company, as I shuddered. A-T-T-W-N has sold more than 100 MILLION copies, and is the world’s best-selling mystery novel, as well as the seventh-best selling book of all time.

The Art-Deco-styled hotel which today perches on Burgh Island was built in 1929, expanded in 1932, and has recently been restored to its 30s glamour. Although Christie had already used the Island as the setting for her most successful story, Christie was unabashed about putting the place to use for a second time. In 1941 she published EVIL UNDER THE SUN, a tale of a murder at the Jolly Roger Hotel (I cannot think of a more unsuitable way for Christie to have renamed this Art Deco jewel…); this time around, crime-solving was performed by Agatha’s fastidious Belgian sleuth, Hercule Poirot.

Burgh Island — a tidal island — is tethered to the mainland by a 270 yard long sandbar. At high tide, the sandbar is submerged, and visitors to the Island are shuttled back and forth on the famous Sea Tractor.

The original Sea Tractor was built in 1930; the current third generation vehicle dates from 1969. The Tractor drives through the water, its wheels getting good traction on the compacted sand of the ocean floor. It all looked a bit top-heavy and tippy to me, but it’s perfectly stable.

Wednesday, July 1, 2015

After the brilliant sunshine of the previous day, the fog and chill which greeted me when I awoke on the morning of July 1st seemed very dreary. The remedy?

Cooking Therapy! I headed into the kitchen of our rented cottage in Dartmouth, and proceeded to bake a dozen of Nan’s Signature Scones. This American’s whipping up of scones while in Devon is, of course, akin to carrying coals to Newcastle. But my scones, which contain tea-infused currants and hefty doses of double cream, are Quite Fine, and I was not at all embarrassed to present them to Anne and David, for their breakfast treats.

Baking, and then Feasting, had elevated my mood, and we set out, heading inland and northwards, towards nearby Totnes, and Dartington Hall.

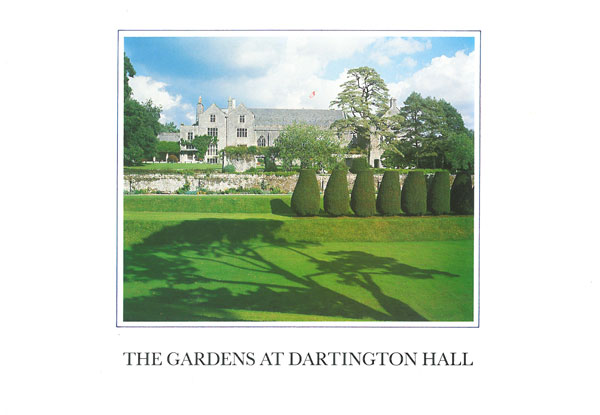

Our Destination: The Gardens at Dartington Hall

The Dartington Hall Trust

near Totnes, Devon TQ9 6EL

Open from dawn to dusk, year-round

Website: www.dartington.org

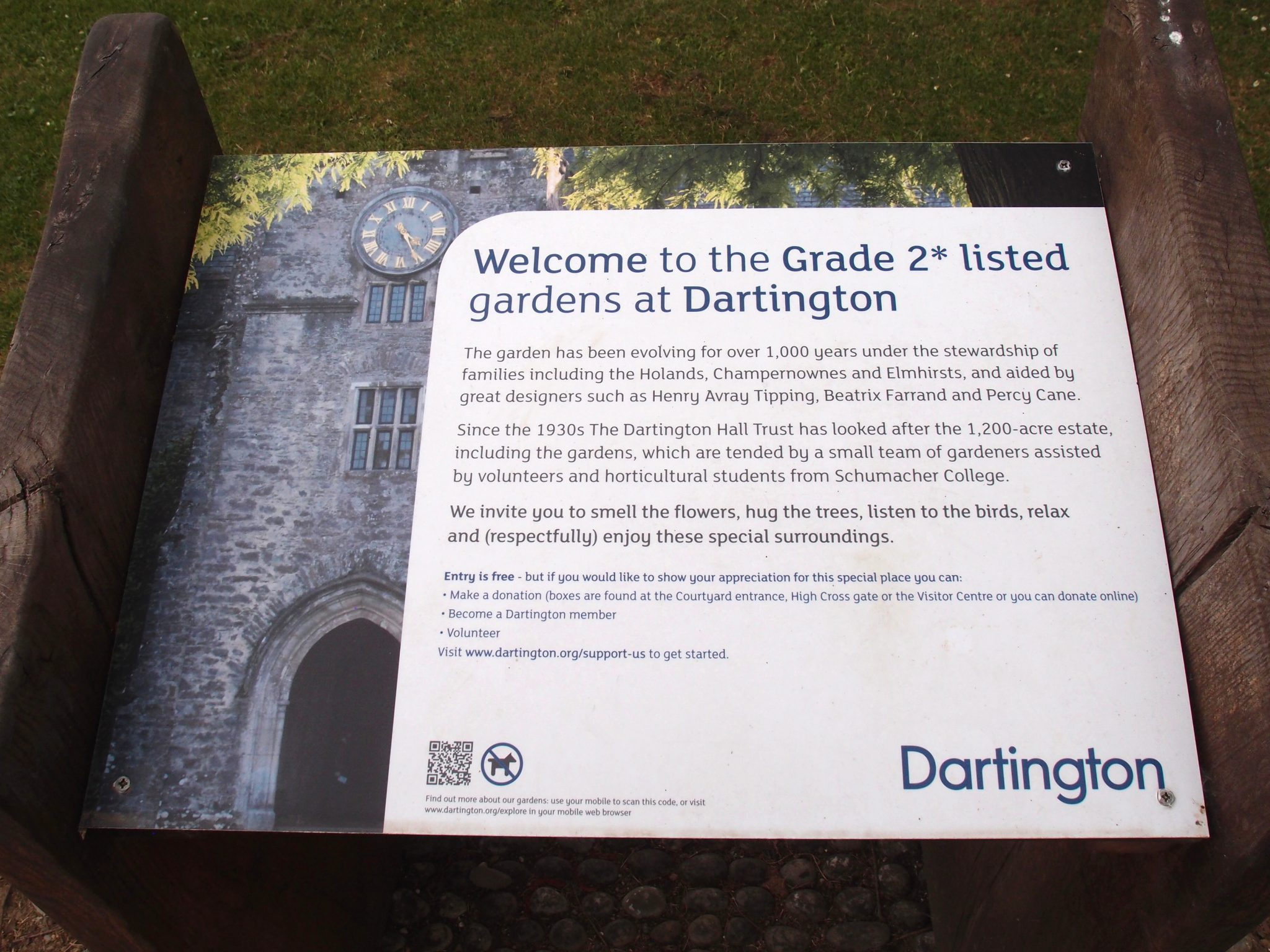

The Gardens at Dartington Hall occupy but a smidgen of the 1200 acres that comprise the entirety of the Dartington Estate. But the Gardens are situated close to the Medieval Hall which is at the heart of the property. Reginald Snell explains the setting, in his history of Dartington’s Garden, titled FROM THE BARE STEM:

“The scene is a partly ruined medieval manor house, standing within a wide bend of the River Dart in South Devon, two miles upstream from the ancient Saxon burgh

of Totnes. Begun in Richard II’s reign, between 1388 and 1399, and built for the king’s half-brother John Holand, Dartington Hall is the only existing house of its period in the country, and has one of the largest residential courtyards surviving from the entire Middle Ages. Its early military associations came to an end in the middle of the

16th century, and the house was lived in by eleven generations of a single Devon family, the Champernownes, who managed the property for nearly four hundred years.

During the 19th century it became impossible for them to keep it in good repair and in 1925 the whole estate was put up for sale. The purchasers were Leonard and Dorothy Elmhirst, both then in their thirties, and it was to become not only their first married home but the centre of a wide-ranging and radically new social experiment.”

Dorothy (born 1887, died 1968) and Leonard (born 1893, died 1974) Elmhirst.

The newlyweds look quite a fun couple…

In 1925, Dorothy Payne Whitney Straight, widow of the American financier Willard Straight and daughter of the statesman & businessman William Whitney, married

Leonard Knight Elmhirst, an English agronomist who was passionately interested in progressive education and rural reconstruction. As one of America’s wealthiest women

( she had inherited her father’s fortune when she was only 17 ), Dorothy could do whatever she damn well pleased, and it became her pleasure to work with her new husband to create their own little utopia at the derelict Dartington Estate.

Feminist, arts benefactress, social and labor reformer, garden designer, magazine founder (The New Republic), founder of schools (the New School for Social Research, in NYC; & 3 institutions at Dartington: a progressive coeducational boarding school, a College of the Arts, and an International Summer School)….Dorothy used her money productively, and also clearly had a ball while spending it.

The Dartington Press has published a comprehensive guide to the Gardens. Here’s an excerpt from Editor Kevin Mount’s Introduction:

When the Elmhirsts first “came here the grounds were neglected and overgrown with weeds. The shrubberies reflected Victorian taste, the Tiltyard was a pattern of formal flower beds, but beneath the worn out surface lay an extraordinarily dramatic landscape setting – a coombe with terraces flowing into a wider river valley, whose folds drifted away southeastwards to the sea.” [Note: A Coombe is a small valley on the side of a hill through which a watercourse does NOT run.]

“It became a matter of freeing the form of the gardens from entanglement; there was never any question of imposing a design upon the landscape. The contours of the lands were used to intensify the natural effects of height, depth and distance. The great trees planted by the Champernowne family…were cleared of undergrowth so that they might stand out in all their grandeur.”

“Dorothy Elmhirst had a large hand in the choice of plant materials. She also had an extensive knowledge and love of trees, shrubs and plants, but to carry the work through she and Leonard had relied on professional help from both sides of the Atlantic.”

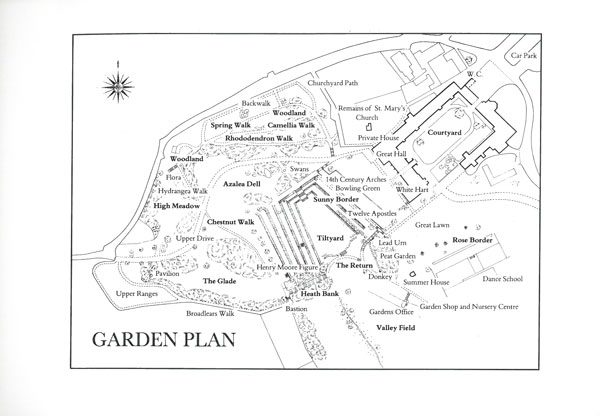

Key Points in the Gardens, listed in the sequence, as you’ll soon see them.

#2: Beatrix Farrand’s Courtyard Paving. #23: Garden Access Bridge, by Peter Randall-Page.#19: Sunny Border.

#20: The Twelve Apostles. #21: The Tiltyard. #17: Swan Fountain. #16: Woodland Walks. #15: Flora statue. #14: High Meadow.#13: The Temple. #12: The Glade. #11: 500-year-old

Spanish Chestnuts. #10: Reclining Figure, by Henry Moore.

#9: The Whispering Circle. #22: heath Bank Steps. #8: Valley Field. #7: Bronze Donkey, by Willi Soukop. #5: Garden Summerhouse.

#4: Jacob’s Pillow, by Peter Randall-Page.

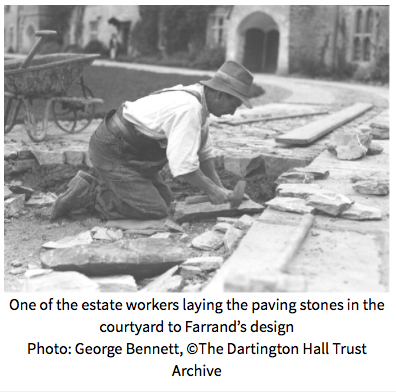

“Most celebrated among their consultants was the American garden designer Beatrix Farrand who became involved in 1933, by which time the Tiltyard had already been cleared and turned to its first use as an open-air theatre. Mrs. Farrand brought order to the Courtyard and designed the cobbled drive that circles the central lawn, overcoming problems presented by awkward ground levels. The following year she began opening the garden out by creating paths and connecting links. Three Woodland walks were laid out and planted.”

In 1914, Beatrix Farrand, a long-time friend of Dorothy’s family, had designed a garden on Long Island for Dorothy and her first husband, Willard Straight. This explains why Farrand, who during her long career had never before been commissioned to design a garden in Britain, was summoned across the Atlantic by Dorothy: the design challenges at the Elmhirsts’ new home were daunting, and Dorothy wanted to work with someone she trusted implicitly.

My long-time Readers will have seen my photo essay about Beatrix Farrand’s most acclaimed American garden: Dumbarton Oaks, in Georgetown (“Gardens & Estates along the Potomac,” published by New York Social Diary, in the summer of 2012). And I’ve done a survey of Farrand’s design contributions to the gardens at The Mount, in Lenox, MA: the home of her aunt, Edith Wharton (see my Diary for Armchair Travelers titled “Grand Gardens of the Berkshire Hills”).

Dartington is the only known example of Farrand’s work outside of the United States, and we’ll begin our garden tour with her deceptively-simple Courtyard.

What’s most remarkable about her work in Dartington’s Courtyard, and throughout the nearby Woodland, is its INVISIBILITY. Farrand’s renovations to the Courtyard, and her creation of three naturalistic Woodland Walks, were so correct that a Visitor to Dartington feels as if she’s strolling through spaces which have existed, unchanged, for centuries. Such subtle and self-effacing work — and from such an acclaimed designer –is rare.

The Courtyard’s Swamp Cypress, originally from Florida, was planted in the late 19th century. Transplanted to England, the tree has grown much higher than it would have, in its native Everglades.

When paving stones were laid in the 1930s, care was taken to not disturb the roots of the Swamp Cypress.

Farrand’s Courtyard drive circles a central lawn. The drive is paved with a mix of cobbles from the River Dart, stone flags, and granite setts.

Inside the Great Hall. In 1925, when the Elmhirsts bought Dartington, only the walls of the Great Hall remained standing. Over the next 10 years, all of the Courtyard buildings were restored. Image courtesy of Dartington Hall.

Behind the Great Hall, this George III lead urn marks the beginning of the gardens. The urn is thought to have been chosen by Beatrix Farrand.

A plaque, inscribed with the first stanza of William Blake’s “Auguries of Innocence,” welcomes us to the Garden. Here’s Blake’s poem, in its entirety:

“To see a World in a grain of sand,

And a Heaven in a wild flower,

Hold Infinity in the palm of your hand,

And Eternity in an hour…

The bat that flits at close of eve

Has left the brain that won’t believe.

The owl that calls upon the night

Speaks the unbeliever’s fright…

Joy and woe are woven fine,

A clothing for the soul divine;

Under every grief and pine

Runs a joy with silken twine…

Every tear from every eye

Becomes a babe in Eternity…

The bleat, the bark, the bellow, and roar

Are waves that beat on Heaven’s shore…

He who doubts from what he sees

Will ne’er believe, do what you please.

If the Sun and Moon should doubt,

They’d immediately go out…

God appears, and God is Light,

To those poor souls who dwell in Night;

But does a Human Form display

To those who dwell in realms of Day.”

The Sunny Border hugs a high stone wall (which separates the Garden from a private bowling green that abuts the Great Hall) and spans the entire length of the eastern edge of the Tiltyard. Dorothy established this Border in 1925, and personally tended it for the rest of her life.

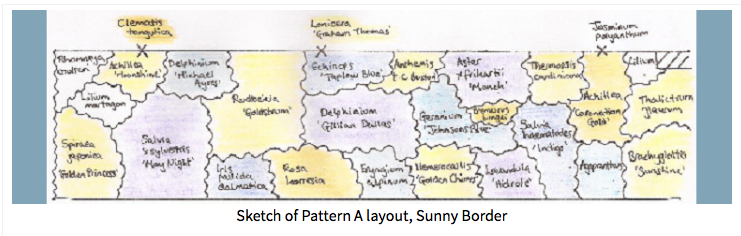

Over the decades, designers Avray Tipping ( her consultant from 1925 — 1930 ), Beatrix Farrand ( 1933 until the start of WWII,in 1939 ) and Percy Cane (Dorothy’s designer from 1945, until her death, in 1968 ) advised Dorothy about her gardens, but the Sunny Border was her hands-in-the-dirt and day-to-day gardening obsession. After Dorothy died, this border in particular suffered. In 1985 Danish-born landscape architect Preben Jacobson (born 1934, died 2012) was brought in to revive the garden beds. He chose plants which flourish in sun-baked growing conditions, and devised planting patterns which rely upon evenly-spaced repetitions of plants where foliage or blossoms of yellow, silver, white, blue or purple predominate.

Sketch of one of Preben Jacobson’s planting layouts for the Sunny Border. Image courtesy of Dartington Hall.

On the left: the Sunny Border.

To the right: a line of highly-sculptural Irish Yews, which are called the Twelve Apostles.

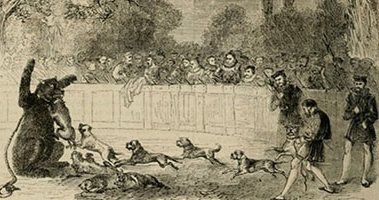

In 1830, twelve Irish yews were planted parallel to the southern-most stretch of the Sunny Border. Per Dartington’s guide to the Gardens, “they may have been planted to shield an 18th century bear-baiting pit in the Tiltyard from the eyes of children (who lived) in the private house.” Bear-baiting (where bears were chained to posts and then attacked by packs of English bulldogs) was a favorite blood-“sport” of the aristocracy, which flourished until 1835, when it was finally outlawed.

Now: on to the Tiltyard. Nothing — absolutely NOTHING — can adequately describe the power of this great, negative space which rests

confidently at the heart of the Gardens.

Through the centuries, these over-scaled cascades of grass terraces which were carved into three sides of a naturally-occurring valley have framed 14th century jousting grounds (thus Leonard’s naming the space: “Tiltyard”) , an Elizabethan water garden, an 18th century bear-baiting arena, and a 19th century Lily Pond, which was then replaced by a formal Victorian garden.

In the 19th century, walkways and shrubbery covered the bottom of the Tiltyard. Image courtesy of Dartington Hall.

When the Elmhirsts first moved to Dartington, they transformed the Tiltyard’s formal garden into an open-air theater, but this idea proved unsuccessful. During the 20 years when the Tiltyard was called a “theater,” only 2 performances occurred there. The slopes and heights of the Tiltyard’s “steps” were far too steep and too tall for people to safely climb. Dorothy conceded that her outdoor theater idea had failed, both practically and esthetically; she finally understood that the true power of the Tiltyard could be unleashed by honoring its pure form. As I walked above, and around, and, finally, into the Tiltyard, I felt I was descending into a giant footprint; a concavity left by an upside-down, somewhat lopsided, and now long-departed ziggurat.

Quite an image, eh? But this is yet another example of how the boldest and best designs can stimulate: both viscerally and intellectually!

No photograph can adequately capture the dimensions of the precipitous slopes of the Tiltyard…especially those on its highest, western side. The super-human scale of the precisely-carved inclines feels simultaneously ancient and modern and inspires awe…along with a great respect for the groundskeepers who must mow the grass there.

My view from the steps at the northern end of the Tiltyard, of The Sunny Border, Twelve Apostles, and Great Hall.

Another view into the Tiltyard, from the Sunny Border. The orange barrier marks the spot where a majestic, 100-year-old Monterey Pine had just been removed. That tree was one of the first Monterey Pines to be imported to England, from California.

Here’ s photo of the Now-Lost Monterey Pine that punctuated the west side of the Tiltyard’s Terraces.

David, supplying human scale, at the north end of the Tiltyard. This flight of steps leads up to the Swan Fountain Terrace.

Nan, on the Terrace by the Swan Fountain, overlooks the Green of the Tiltyard. Part of the charm of the Tiltyard are the ways in which views of its precipitous slopes are often hidden, from other areas in Dartington’s Gardens. Photo by Anne Guy.

To the north of the Tiltyard is a circular terrace that frames a Swan Fountain.

The Swan Fountain, in Springtime, when the shrubs in Percy Cane’s Azalea Dell begin to flower. Image courtesy of Dartington Hall.

Path leading into the Woodland, where Beatrix Farrand planted Yew, Bay and broadleaved Hollies as background material for camellias, magnolias and rhododendrons.

The statue of Flora marks a transition from Beatrix Farrand’s landscaping to that of her design-successor, Percy Cane.

As World War II ended, the Elmhirsts began to search for a new garden designer. In 1945, Percy Cane, who was a well-established English landscape architect, paid his first visit to the Elmhirsts’ Estate. Percy and Dorothy clicked, and so began their twenty-three-year long collaboration. Whereas America-based Farrand had only been able to make a total of four site visits, Cane, who was based in London, eventually traveled more than 50 times to Dartington, as he supervised the construction of new stairways, terraces, structures, seating areas, pathways and gardens in eight distinct but related projects.

Cane’s goals were numerous. Farrand had, with her Woodland Walks, begun to extend the gardens and link them to the surrounding landscape. It now fell to Cane

to continue those expansions. He also devised new sightlines throughout the gardens, and worked on a master plan to link all of the garden’s sections, both old and new,

with enticing vistas and graceful paths. And major clearing of overgrowth at the peripheries of the garden revealed stunning views out across Devon’s rolling countryside. Whereas both Dorothy Elmhirst and Beatrix Farrand were tree lovers and plant experts, Percy Cane never professed himself a horticulturalist; his métier was the manipulation of space. Because of his near-quarter-century of work at Dartington, we can intuitively explore the sprawling grounds. With his new sightlines and pathways Cane injected an essential clarity and continuity into what had previously been a series of beautiful but unconnected garden areas. Despite its seeming complexity, this is a Map-Optional-Garden!

High Meadow, designed by Percy Cane in 1949, arose from a completely-cleared corner of the property, where cutting flowers had previously been grown.

This was my view downhill, through The Glade, as I stood in The Temple. Cane created The Glade by carving away undergrowth. He kept only the most shapely trees; then planted a central sweep of grass, flanked by shrubs.

A spectacular cluster of 500-year-old Spanish Chestnut Trees towers over the western edge of the Tiltyard. The Chestnuts are Dartington’s most precious specimens, and were planted by the first of the Champernownes, when that family acquired the property.

Still standing by the Moore sculpture, I then turned to the south east, and saw the

entrance to Valley Field, below me.

This is what touring a garden with me looks like: I’m wandering, alone, as I take in my surroundings and then frame the views with my camera. As I took the picture you’ve just seen, Anne photographed me.

The Whispering Circle (aka The Bastion) , built by Percy Cane, is a look-out that’s adjacent to the Moore sculpture, and near the top of the Heath Bank. From the Circle…on a clear day… one can see for miles, to the south east. This Circle also produces a peculiar sound effect. I asked Anne Guy to remind me about that and she replied : “It seems that the person standing at the focal point in the centre of the york stone paved circle will receive the sound (of her whispering as it ) is reflected off the parabolic wall (behind the Circle) to give an almost stereophonic effect. As to describing how it ‘feels,’ it’s tricky…it is a kind of internal echo through the body…you can FEEL (the sound you’re making) rather than hear it.”

Stairway below the Whispering Circle. During 1947 and 1948, Percy Cane built 71 steps to complete a path which would connect The Glade and the Whispering Circle to the long slope of Heath Bank,

and, ultimately lead visitors to the mouth of the Valley Field.

The Valley Field, as seen from the Heath Bank Steps, which are at the south end of the Tiltyard. In the late 1950s, Percy Cane cleared many acres of scrub woodlands, and thus opened the longest vista in the Gardens. He then planted multitudes of Japanese cherries, maples, scarlet oaks, and sourwood trees in Valley Field.

As Dorothy began what was to become her 43-year-long redesign of the Gardens, she and Leonard also founded their progressive, coeducational school. Dartington Hall School was intended to offer the polar opposite of the traditional English boarding school experience. In 1926, the Elmhirsts welcomed their first students with these promises:

“No corporal punishment, indeed no punishment at all; no prefects; no uniforms; no Officers’ Training Corps; no segregation of sexes; no compulsory games, compulsory religion or compulsory anything else; no more Latin, no more Greek; no competition; no jingoism.” (Take that, Eton, Marlborough and Hogwarts! )

In 1930, the Elmhirsts engaged architect William Lescaze to design a headmaster’s house with a cutting-edge style that would match the School’s innovative curriculum.

HIGH CROSS HOUSE: built in 1932 for the Headmaster of the Dartington Hall School. Photo by Anne Guy.

Architect Lescaze, and Headmaster W.B.Curry worked together to create a “machine for living,” and novel concepts such as kitchen ergonomics were explored.

During the National Trust’s brief stewardship of High Cross House, this sign was on display. Photo by Anne Guy.

But local contractors, who were inexperienced in non-traditional building techniques, made mistakes, which have ever since made the preservation of High Cross House costly and complicated. Headmaster Curry lived in his high-maintenance dream house from 1932 until his retirement in 1957. In its heyday, 300 students were enrolled at the School. In 1987, the School was closed.

In January of 2012, High Cross House, which is just a short stroll from the Estate’s Gardens, was leased to the National Trust for 10 years. Anne and David Guy, those ever-alert travelers, were among the first to visit the House, which is considered to be one of the United Kingdom’s best examples of modernist architecture.

But by December of 2013, the National Trust had already declared their experiment of managing a house built in the International Modern style to be a failure. Clearly, England’s four million National Trust members, who so love touring traditionally-styled properties, have little interest in this rare example of architecture’s Modern Movement in Britain. The BBC reported the dreary news:

“The Trust has activated a pull-out clause in the lease after the house attracted 11,000 fewer visitors than it needs to break even. Dartington Hall Trust, which owns the property, said there were no current plans to reopen the house. In 2012, 21,000 people visited the house, but the National Trust needed 32,000 to visit for it to be

‘financially sustainable.’ ”

And so today, High Cross House, which the National Trust called one of “the top five Modernist houses” in the United Kingdom, remains closed and untended. We are fortunate that Anne Guy took photos of the House in 2012, while it was being well cared for.

Thursday, July 2, 2015

The previous morning had greeted us with cold and fog, but Thursday’s weather had upped the ante, with torrential rain and winds. Despite all, we bundled up, turned our backs upon our cozy Dartmouth cottage, and forged onward and outward, into the deluge. We traveled east, across the River Dart, to yet another garden: this one on Kingswear’s seacoast.

Vehicles packed tightly, on the auto-ferry.

This ferry uses cables, both for its propulsion and guidance: clever, and energy-efficient!

Our destination: Coleton Fishacre

Brownstone Road

Kingswear, Devon TQ6 0EQ

Website

https://www.nationaltrust.org.uk/coleton-fishacre

A fair-weather view of Rupert and Dorothy D’Oyly Carte’s opulent, 1920s, seaside retreat. Image courtesy of the National Trust.

But could we have possibly been greeted with a spookier, or more atmospheric sight, than this one…

…I think not! For anyone who has shivered while reading Daphne duMaurier’s REBECCA, the stone house which loomed ahead seemed a cousin of the author’s haunted Manderley, which she had placed in nearby Cornwall.

The Forecourt is paved with granite, laid in a radiating pattern. The dimensions of this front entry drive were determined by the turning radius of the D’Oyly Cartes’ Bentley.

[Note: Southern Cornwall’s topography is a continuation of Southern Devon’s. England’s southwestern peninsula is etched by rivers, and fissured by valleys. High rolling fields terminate in cave-studded cliffs, which rise above rocky beaches, that curve around secret coves . Apart from a river — we’ll have to make do with a stream — ,

in Coleton Fishacre’s 24 acres of gardens we’ll eventually find all of these geographical features.]

As we sloshed through a heavy downpour toward the fog-shrouded House, it crossed my mind that, lurking inside, there ought to be a National Trust Docent who looked like a Mrs.Danvers-Clone.

Judith Anderson played Mrs.Danvers in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1940 version of REBECCA (which, though accurately depicting Menacing Atmospherics, fudged a major plot point, and in so doing robbed duMaurier’s story of its complexity and ultimate impact).

We crossed the somber, stone threshold. And inside? Nary a Mrs.-Danvers-Clone-Docent to be seen. Instead, I was surprised to discover a pristine, light-filled interior.

The National Trust describes the interiors as “Art Deco in Devon,” but this characterization is incomplete. The house’s spaces — where whitewashed walls meet ceilings in smooth, continuous curves; where rooms are sparingly decorated with a tightly-edited blend of accents taken from Arts and Crafts, Art Nouveau, Art Deco , Oriental and Baroque styles — are serene and comforting. There’s no Jazz-Age Jitteriness in those rooms…no brittle, Art-Deco Sheen in the place.

For the next hour, my companions and I explored the house, as we waited for the weather outside to improve enough to make our eventual garden stroll something other than a soaked-to-the-skin ordeal.

The National Trust’s guidebook introduces us to the property:

“In the 1920s Rupert and Lady Dorothy D’Oyly Carte were sailing along the south Devon coast. Looking for a country retreat, they were inspired to make this beautiful valley running down to the sea the site for an elegant home where they could entertain in style and indulge their passion for the outdoors.”

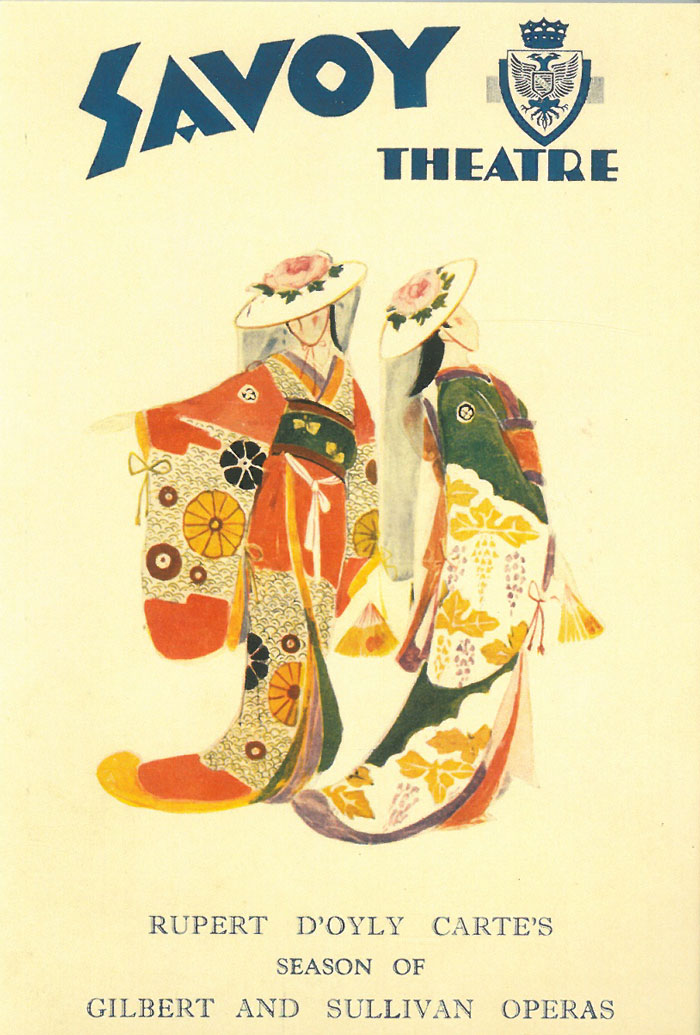

Rupert D’Oyly Carte (born 1876, died 1948). Son of the impresario and hotelier Richard D’Oyly Carte, Rupert revitalized the family’s Gilbert and Sullivan opera company, which was based at the Savoy Theatre. He also greatly improved his empire of hotels,

with renovations to Claridge’s, the Savoy, and the Berkeley Hotel. Despite working non-stop each week in London, on weekends Rupert returned to Coleton Fishacre, where he supervised all aspects of his gardens.

Lady Dorothy Milner Gathorne-Hardy D’Oyly Carte (born 1889, died 1977). The 3rd and youngest daughter of the 2nd Earl of Cranbook, Dorothy married Rupert in 1907, and became a full partner with him in the design of their gardens at Coleton Fishacre. In 1932, after their 21-year-old son Michael died in an auto accident, their marriage began to crumble: in 1941 Rupert divorced Dorothy for adultery. Soon thereafter, she moved to the Bahamas, where she married St.Yves de Verteuil who was her co-respondent in the divorce case.

The National Trust’s history continues: “Building for Coleton Fishacre began in 1923 to the design of Oswald Milne, who had been a protégé of Sir Edwin Lutyens. Inspired by the influence of the Arts and Crafts Movement and its beliefs in simple design and high standards of craftsmanship, the house responded to its landscape and literally grew out of it. The stone came from a quarry in the garden and the design embraced the beauty of the surroundings. “

While adeptly interpreting the Arts and Crafts style in his busy practice of building country homes, Oswald Milne also became a pioneer in the design of Art Deco interiors, throughout Britain. Milne’s most famous interiors were his 1929 transformations of Claridge’s Hotel (also owned by Rupert D’Oyly Carte), in London.

Oswald Milne’s most acclaimed Art Deco interiors were designed for Claridge’s Hotel. This photo taken in the 1930s.

Let’s begin our tour of the House, which the National Trust now presents largely with furnishings that are correct to the period, but are not originals from the D’Oyly Cartes’ time there. In 1930 COUNTRY LIFE published an extensive photo-spread about the interiors, and the National Trust referred to those pictures as they sought replacement furniture and accessories. [ Note: Where original furnishings are on display, I’ll identify them. ] Insofar as Oswald Milne’s architecture goes, the rooms remain as he built them, in 1923.

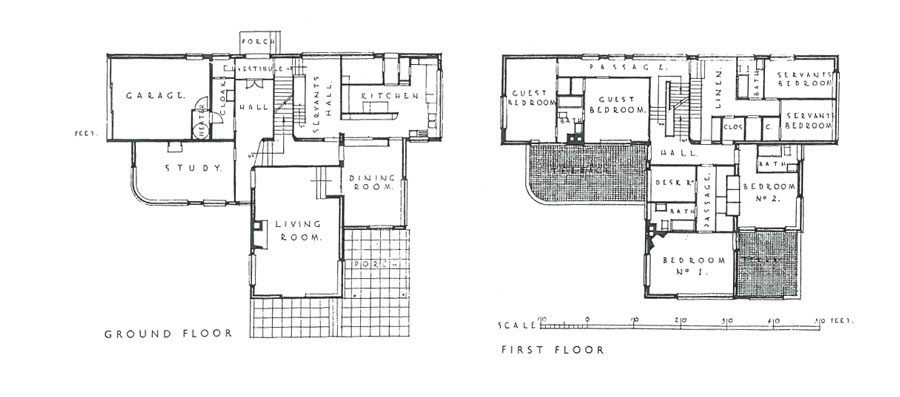

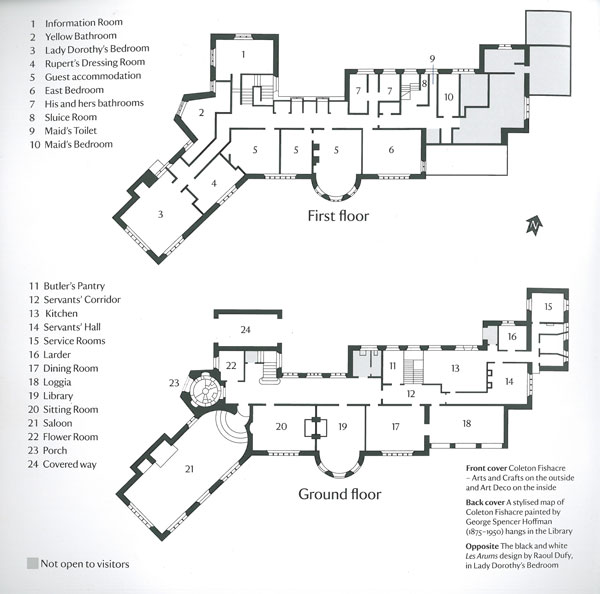

We’ll follow the National Trust’s recommended route, and will pass from the circular Front Entry Porch, through the Front Hall and its adjacent Flower Room, and then directly upstairs, to Lady Dorothy’s Bedroom.

Lady Dorothy’s Bedroom — one of the largest of the House’s seven bedrooms — is today presented to appear just as it did, when photographed by COUNTRY LIFE, in 1930.

From the expanses of windows on two sides of Dorothy’s Bedroom, she could look out across the nearby Rill Garden, and also down to the ocean, over extensive gardens,

planted in the steep, narrow valley.

Lady Dorothy’s dressing table (reproduction) and stool (original). The upholstered stool is the Very One upon which Dorothy sat, and is covered

with new yardage of the same black and white fabric (style: Les Arums, designed by Raoul Dufy) that was first used, throughout this bedroom.

In Dorothy’s Bedroom: the over-mantle painting is original to the House, as is the cupboard to the right of the fireplace. The near-black Axminster carpet was woven to replace the original.

Rupert’s Dressing Room (adjacent to Dorothy’s Bedroom) :

Rupert’s Dressing Room Sink. For all of the bedrooms’ sinks and surroundings, these powdered glass tiles — made from recycled glass —

were installed. Rupert had used identical materials when he refurbished his Savoy Hotel, in London.

Guest Bedroom in Turret:

His and Hers Guest Bathrooms, as described by the National Trust:

“Opposite the (guest) bedrooms are the bathrooms, for male and female guests respectively. They retain many of the their original fittings including the Doulton & Co. sunken baths. The green glass soap dishes and blue glass sponge bowls were recreated especially for the house by Dartington Glass, as the originals were in pieces.”

“The plain tiles of the walls are interspersed with pictorial tiles designed by Edward Bawden ( 1903—1989 ). The tiles depict scenes of outdoor life, so appropriate for Coleton Fishacre, and include both traditional sports like fishing and more modern interests such as motorcars.”

Sunken Tub in a Guest Bathroom, with glass dishes from Dartington Glass. Yes….that’s the same Dartington we’ve just visited. In the 1920s, when Leonard & Dorothy Elmhirst established the Dartington Hall Trust, they realized that they could regenerate Southern Devon’s

economy by retraining residents in many highly-skilled trades. Those residents then went into business as cheese-makers, carpenters, farmers and glass-blowers. Dartington Glass was founded in the early 1960s, and is still prospering.

Here’s a sampling of Edward Bawden’s bathroom tiles, which serve as a template for How to Behave Whilst Visiting a Country House:

Leaving the Guest Bathrooms, I looked back down, along the Bedroom Floor’s central corridor:

Bedroom Corridor. The ceiling light is original to the House. Note: the entrance to Lady Dorothy’s bedroom is at the far end of the hall.

As the National Trust explains: “Simplicity, quality and finish are key to the interiors. The rooms, and the corridors in particular, are almost austere in their lack of ornament.”

The East Bedroom:

When his marriage to Dorothy disintegrated, Rupert moved into the East Bedroom, which also had fine views of the garden, and of the ocean.

View from the East Bedroom…trust me, despite the blanket of fog outside in this photo, you WILL soon see the gardens. Throughout the house, all of its mullioned windows have ironwork fittings, and are set above black Staffordshire tile sills.

From the East Bedroom, we headed downstairs, via the servants’-stairs, to the Servants’ Corridor, Kitchen, and the House’s other utilitarian rooms.

The Servants’ Hall has a fine view (really) of the gardens. The D’Oyly Cartes employed a butler, housekeeper, housemaid, cook, and chauffeur, all of whom lived on the Estate. Their gardens required additional, seasonal staff: a landscape architect, a Head Gardner, and six gardeners.

The Drying Room, where wet clothing was hung, after it had come from the Laundry. There was also a Brushing Room, used (you guessed it) to brush clothes, and to clean shoes and boots.

The Dining Room. Per the National Trust’s guidebook:

“In contrast to all the other rooms at Coleton Fishacre, the majority of the furniture in the Dining Room is original to the house. This room, with its custom-made furniture and easy access to the garden, perhaps best exemplifies what the D’Oyly Cartes wanted from their weekend retreat.”

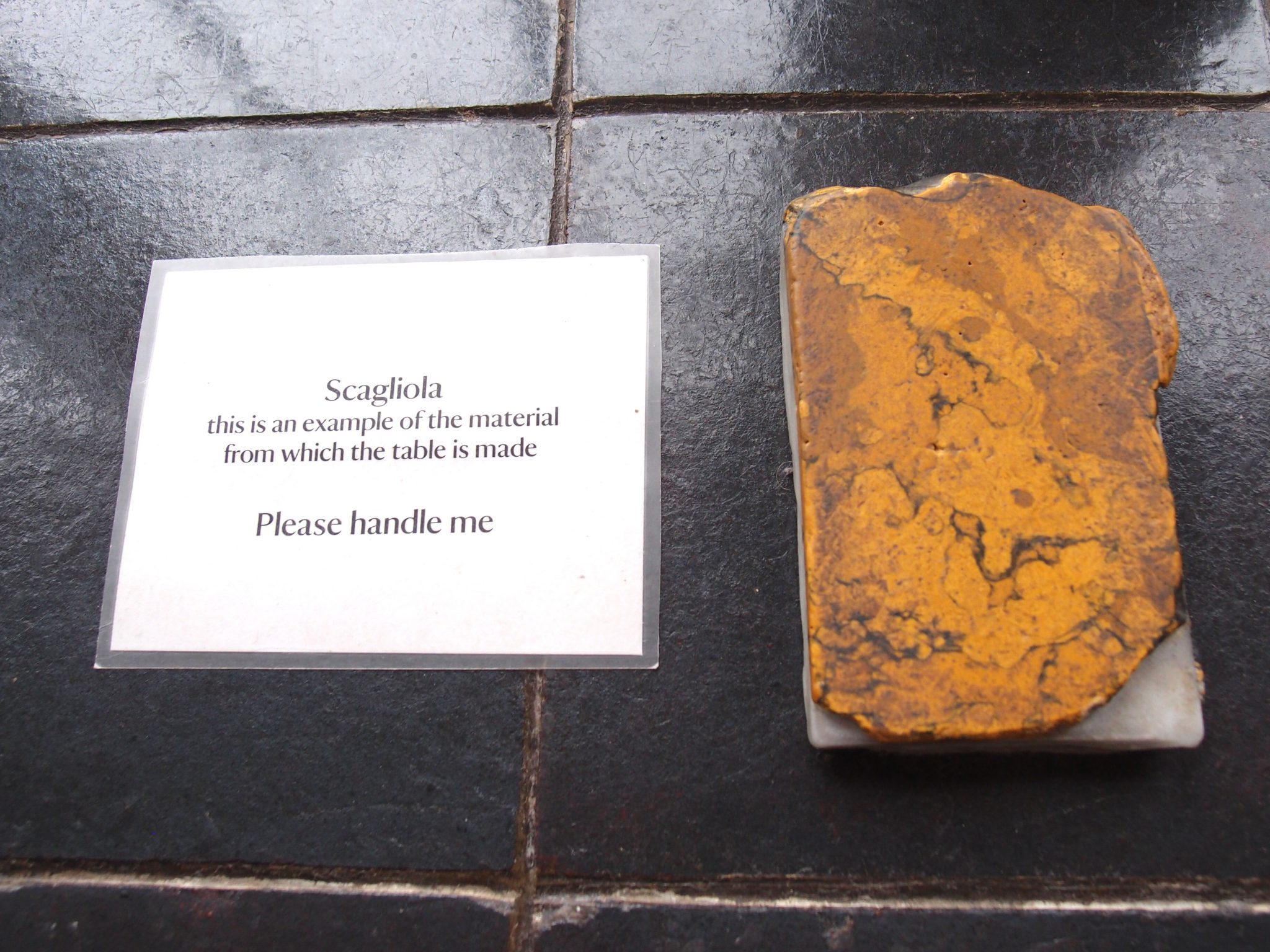

“Most of the furniture was commissioned by the D’Oyly Cartes from their architect Oswald Milne, including the walnut sideboard, dining table and pair of side tables, which could be moved to the main table. The colour of the scagliola table tops, made of plaster of Paris, pigments and animal glue to imitate marble, was chosen to evoke the sea.”

Miraculously, the fog had begun to lift. Here’s our Dining Room view of the Terraces, over the Upper Pond Garden, and across to the West Bank.

The Loggia … a most inviting outdoor space, even on a stormy day:

The Ground Floor’s light-filled Central Hallway:

The Library. This room is described by the National Trust as:

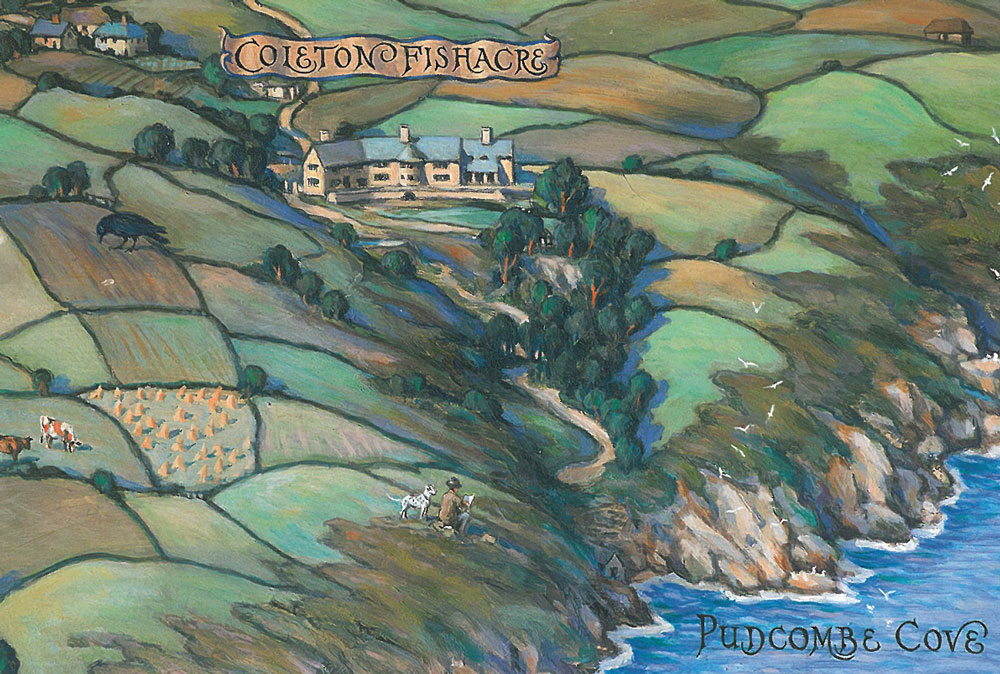

“The centre of the house, a cozy and intimate room with its bow window to the south. It is fitted with simple pine shelves and lit by simple translucent alabaster uplighters, original to the house. Dominating the room, above the travertine marble fireplace, is a painted map of the south Devon coast around Coleton Fishacre, which incorporates a wind dial. The painting is by George Spencer Hoffman ( 1875—1950 ), and is a near-realistic bird’s-eye view and also the depiction of Rupert overlooking the combe with his favorite Dalmatian. This was the spot where Rupert’s ashes were (eventually) scattered.”

The Sitting Room:

As someone who is addicted to both tea and books, this Sitting Room arrangement pushes ALL of my buttons…

And the final stop, on our House Tour: The Saloon.

As described by the National Trust:

“The entrance to the Saloon is intentionally impressive and theatrical, and shows the ingenious way in which Oswald Milne dealt with awkward changes in level of the site, using them to great advantage.”

My first view of the Saloon. I’m not sure I agree with the National Trust’s positive assessment of this nearly 40-foot-long space. Standing in the doorway to the Saloon, I felt as if I was about to begin walking a Plank….

But, once down the steps, and into the Saloon-Proper, the extreme linearity of this room was offset by expanses of garden-facing windows, and French doors.

But, to my eyes, the most striking and successful decorative addition to the Saloon is the

carpet, which was custom-made in the late 1930s by American textile designer Marion Dorn. The carpet we see today is an exact reproduction of Dorn’s floor covering.

A turns-out-she-was-a-talented-pianist and fellow-Visitor was invited to play the

Saloon’s Bluthner rosewood grand piano (dating

from 1895-96, and which was bought for this room by the National Trust, in 2002).

Having enjoyed our young musician’s impromptu piano performance, we proceeded to the front porch, where we were cheered to discover that the morning’s chilly torrents of rain had been replaced by a soft, warm drizzle. ‘Twas time for our Garden-Tromp.

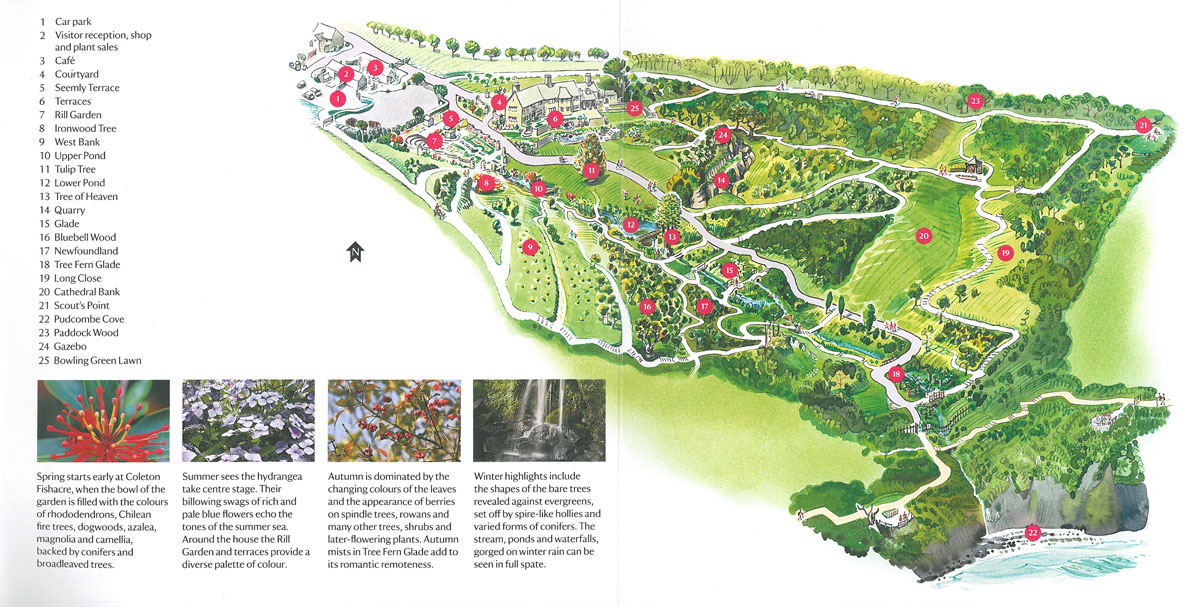

The National Trust introduces Coleton Fishacre’s gardens this way:

“The geology of the area — acidic soil overlying Dartmouth shale and with water running through the valley in many areas — makes this garden suitable for a wide range of plants. One of the botanically richest summer and late-summer gardens cared for by the National Trust, the garden at Coleton Fishacre includes succulents from the Canaries in the upper parts of the garden, and tree ferns from New Zealand in the cooler parts of the valley. The atmospheric humidity is high beneath the tree canopy and makes perfect conditions for many moisture-loving plants. This, together with the mild climate, enables species that can survive outside in few other places in Britain to thrive and grow to an exceptional size at Coleton Fishacre.”

“Rupert and Lady Dorothy D’Oyly Carte were both enthusiastic gardeners and, keen to ensure the success of their new garden, sought advice from Edward White of the landscape designers Milner & White. Under his guidance, and even before the house had been completed, the planted a woodland shelterbelt of pine, holm oak and sycamore on the bare ridges to provide protection from the strong prevailing winds. With this belt of trees in place, Rupert and Lady Dorothy could then concentrate on planting the garden itself, experimenting with trees and shrubs from around the world. The planting took account of future vistas and views, testimony to their far-sighted vision, which is still evident today.”

“The book of planting plans kept by Rupert from about 1928 to 1947noted plants in all 78 beds as they were acquired, together with details of the source and planting location, with additional comments about their performance noted later. Altogether the D’Oyly Cartes planted over 10,000 trees and shrubs.”

Pictures from our long ramble through the gardens will appear in their actual, meteorological sequence. By early afternoon, the weather had begun to improve: the fog lifted…the rain calmed itself into a drizzle…and after a bit even the drizzle was exhausted. A light breeze arrived, clouds scudded out to sea, and, suddenly, soft warm air and brilliant sunshine transformed Coleton Fishacre into a place which felt and looked entirely new. Remember, if you’re displeased by England’s weather conditions, be patient: odds are, the skies’ll change.

![Front of House, with archway to Service Court. The Service Court is tucked into the hillside, to the north of the House. The exterior of the House is constructed from Dartmouth shale stone, which was blasted from rock in the lower part of the D’Oyly Cartes’ valley. That same shale was also used to build the garden’s terraces and walls. The roof is shingled with Delabole slate. [Note: The Delabole slate quarry is in nearby Cornwall. The quarry has been in continuous operation since the 15th century, and is the oldest working slate quarry in England.]](https://nanquick.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/p7023959.jpg?w=930)

Front of House, with archway to Service Court. The Service Court is tucked into the hillside, to the north of the House. The exterior of the House is constructed from

Dartmouth shale stone, which was blasted from rock in the lower part of the D’Oyly Cartes’ valley. That same shale was also used to build the garden’s terraces and walls. The roof is shingled with Delabole slate. [Note: The Delabole slate quarry is in nearby Cornwall. The quarry has been in continuous operation since the 15th century, and is the oldest working slate quarry in England.]

We’re headed toward the Terraces which are on the south side of the House. Towering above us: the Southwest wing of the House, with Saloon on the ground floor, and Lady Dorothy’s bedroom on the upper floor.

I inspect the Top Terrace. The Saloon and the Loggia both open directly onto this Terrace. Photo by Anne Guy.

Climbers are happy, clinging to the Dartmouth Shale Stone walls of the House. Many of these climbing plants survive from the D’Oyly Cartes’ time.

At the southeast corner of the Top Terrace, a flight of slate steps leads to the Middle and Lower Terraces

At the east end of the Bowling Green Lawn, a grass path leads to the Gazebo; and, farther east, to Cathedral Bank; and finally, to Pudcombe Cove.

A tantalizing view of that path, which is flanked by borders planted with Exotics. We’ll see where this path leads, in a little bit…

![The Pool on the Middle Terrace is fed by a stream that originates beyond the north side of the House. The otter was carved from Cornish Polyphant soapstone to replace an earlier Portland stone sculpture. [A note for those of you who are stone-lovers: Portland stone is a limestone which, since the Roman occupation of England, has been quarried on the Isle of Portland, in Dorset, which is just to the east of Devon.]](https://nanquick.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/05/p7023972.jpg?w=930)

The Pool on the Middle Terrace is fed by a stream that originates beyond the north side of the House. The otter was carved from Cornish Polyphant soapstone to replace an earlier Portland stone sculpture.

[A note for those of you who are stone-lovers: Portland stone is a limestone which, since the Roman occupation of England, has been quarried on the Isle of Portland, in Dorset, which is just to the east of Devon.]

The Rill Garden was designed by Oswald Milne. This hillside garden is bisected by a narrow, canalized stream and a small, central pool. Lady Dorothy originally planted many pastel-colored rose bushes here, but those shrubs failed, in the seaside air. Semi-tender perennials now fill the Rill Garden.

In 1926, while the House was being constructed, two dams were built in the stream which runs from the property’s western hillside, down to the eastern seashore.

The Upper and Lower Ponds were thus formed.

Lush plantings around those bodies of water now give each Pond a natural appearance.

View of the House’s Saloon wing, from the Rill Garden. All of the stone walls, terraces and steps in the gardens were built as the House was being constructed.

The Rill Garden’s stream is routed downhill–toward the Upper and then Lower Ponds–through this opening, which is beneath the lowest lip of the Rill Garden.

Proceeding downhill from the Rill Garden, we strolled past the lushly-planted Upper Pond borders. To the rear of the House, those tall pines are just a few of the 10,000 trees which were planted by the D’Oyly Cartes.

We’re getting very close to the ocean now, and pass through the Tree Fern Glade, with its New Zealand

tree ferns.

We followed the Coastal Footpath to Scout’s Point (aka Lands End), where we were presented with this rainy view of Pudcombe Cove.

In Pudcombe Cove, “the D’Oyly Cartes created a reinforced concrete tidal bathing pool and jetty, built between 1929 and 1931. The cove was accessed by steep concrete steps that zigzagged down the cliff. From the sea, the cove could be reached by the jetty, built from shingle from the beach and running out 60 metres into the sea. Considerable investment and effort were made to provide comfort and convenience for the family and guests. Facilities included a changing hut, a sun-bathing platform and cold-water shower.”

“The Cove has been inaccessible to visitors since 2001, due to the perilous state of the steps, caused by coastal erosion and rock falls. The National Trust, in line with its policy not to interfere with natural coastal processes, is allowing nature to take its course, which will mean the eventual loss of” all of the D’Oyly Cartes’ additions to the Cove.

Turning away from the ocean, we began our long climb back to the House, up the seemingly endless steps of the Long Close,

which are on the eastern slopes of the Cathedral Bank.

Half-way up the Long Close, I paused to gain my breath. Turning back toward the Ocean, I was rewarded with this wonderful, albeit still-rain-soaked, view.

Having finally reached the Gazebo, I looked down, into the site of the former Quarry, from which all of the House and Garden’s stone was blasted. During the years of construction, a temporary railway track was installed between the Quarry and the House site,

to facilitate the transport of tons upon tons of shale.

Leaving the Gazebo (don’t worry, I’ll show you the Gazebo, once the weather clears…) , we headed back toward the Bowling Green Lawn, through a garden planted with Exotics such as yucca, bromeliad, protea and echium.

Soggy and famished, ‘twas time for a dry-out and a lunch-break, and we retreated to the Visitor Centre Café.

But just as we were polishing off our meals, sun abruptly shined down upon Coleton Fishacre….which meant that we’d have to take another trot around the gardens.

And so we approached the House for the second time that day: and the place had been Utterly Transformed.

In my first circuit through the gardens, I’d missed the area closest to the entrance drive: Seemly Terrace.

On Upper Terrace, by the Loggia: the It’s-Time-To-Trudge-Back-Up-The-Hill-Bell. As the D’Oyly Cartes approached the end of a long summer day at their private beach on Pudcombe Cove, their butler would ring this bell,

to signal that the time was nigh for cocktails, back at the House.

The rectangular pool and fountain on the Lower Terrace (with the Library’s Turret wing directly above).

The retaining walls of the Lower Terrace are covered with Mexican daisies.

Let’s wallow some more in the COLORS of the Hot Border. The stairs in the background lead up to the Bowling Green Lawn.

And Finally: a decent Ocean View, from near to the House. We’re on the Terrace Steps,

at the corner of the Bowling Green Lawn.

And I suppose I ought to mention the ANTS. This is a view of the West Bank, from the Terrace Steps. The West Bank’s most peculiar feature: its large anthills, which have remained undisturbed for hundreds of years. The huge tree in the center of the Bank is a Persian Ironwood.

The hexagonal Gazebo, with stone pillars and wooden trellis supporting wisteria, has a spectacular ocean view. When first built, the Gazebo also had a clear view, back to the House.

My view from the Gazebo, down to the path which leads from the Quarry, through a wooded area, and further downhill to Cathedral Bank.

To have been able to visit three such splendid gardens as Overbeck’s, Dartington Hall, and Coleton Fishacre — and on consecutive days — was an enormous privilege. Sometimes as I travel, this abundance of daily wonderfulness begins almost to seem normal. But afterwards comes the necessary Reality Check … provided by my most-of-the-time-quiet life at home, here in rural New Hampshire. I’m glad that distance — in time and in miles — ultimately separates my garden touring from the making of these reports about my journeys. From those separations come perspective.

The most conventionally beautiful bits of landscaping (think “Capability Brown,” who I admire less and less, and about whom I’ll write some more, in future) — those places that obligingly serve up the generic pleasures of lush borders and tasteful ornamentation and long views -– are sometimes not the gardens which most deeply resonate, months later, as I’m sitting in my office chair and sifting through my photo archives, and reviving my memories.

Instead, the gardens that most make me ache for another ramble through them are those where the sensual experience of garden strolling is enriched by information that personalizes each landscape. Learning about the travails and quirks of the people who created those places makes me feel as if I’m visiting a Home, instead of an Attraction. It’s essential that we remember that each of these magical environs was at first just a figment of an imagination. Only through subsequent leaps of a founder’s faith — and accompanied by enormous expenditures and sustained efforts — were those imagined places then transformed into real gardens. In the most satisfying of England’s historically-significant gardens, the dirt and stone and plant material which astound today’s bus-loads of garden-gawkers were all originally chosen to solidify the visions of only one or two souls. The best gardens are the embodiments of the dreams of their makers: such gardens were not made to please you … or me!

I think of the brilliant and nutty Otto Overbeck, who attempted to cure the ills of mankind (administering one electrical jolt at a time), while he also made a huge leap into the Horticultural Unknown (ordering 3000 palm trees be planted in his English garden) .

I marvel at the prodigious energies of Dorothy and Leonard Elmhirst, who restored their ancient Dartington Hall, while they simultaneously nurtured the talents of innovative landscape designers and avant garde architects…and who then (never content to rest upon their laurels) also established progressive schools and local businesses.

The personalities of Rupert and Dorothy D’Oyly Carte seem to have been less vibrant (or were perhaps better concealed) that those of Overbeck, and the Elmhirsts. But with their exquisite appreciation of the potential of those 24 acres at Coleton Fishacre, the D’Oyly Cartes managed to create one of the World’s rare places. At their home by the sea, landscape and natural resources and architecture and garden structure and horticulture all give the illusion of having been united — without artifice or effort — into

something resembling paradise.

Before we arrived at Coleton Fishacre, Anne Guy told me how she’d reacted, during her first visit there. While chatting with a National Trust staff member, she’d said,

“I’d like to live here.” The Trust staffer replied, “Get in line!”

Copyright 2016. Nan Quick—Nan Quick’s Diaries for Armchair Travelers. Unauthorized use and/or duplication of this material without express & written permission from Nan Quick is strictly prohibited.

4 Responses to Part Two. A Well-Spent Week in Southern Devon, England